kottke.org posts about poetry

An excerpt from Elisa Chavez’s poem “Revenge” in the Seattle Review of Books:

Since you mention it, I think I will start that race war.

I could’ve swung either way? But now I’m definitely spending

the next 4 years converting your daughters to lesbianism;

I’m gonna eat all your guns. Swallow them lock stock and barrel

and spit bullet casings onto the dinner table;

I’ll give birth to an army of mixed-race babies.

With fathers from every continent and genders to outnumber the stars,

my legion of multiracial babies will be intersectional as fuck

and your swastikas will not be enough to save you,

This is a powerful poem, and I laughed out loud so hard to the “This is a taco truck rally and all you have is cole slaw” line.

In this video, American poet Maya Angelou recites her poem Still I Rise, which was published in 1978. The recitation includes some opening remarks…the poem begins like so:

You may write me down in history

With your bitter, twisted lies,

You may trod me in the very dirt

But still, like dust, I’ll rise.

Does my sassiness upset you?

Why are you beset with gloom?

‘Cause I walk like I’ve got oil wells

Pumping in my living room.

Just like moons and like suns,

With the certainty of tides,

Just like hopes springing high,

Still I’ll rise.

Wonderful. That little chuckle after “Does my sassiness upset you?” — amazing. And it’s interesting to see how she deviates from the written text in her performance, a reminder that even the finest things in the world — like freedom, like liberty, like democracy — need to be refreshed and remade anew in order to remain vital. (via swiss miss)

From Mark Forsyth’s The Elements of Eloquence, a reminder of the rules of adjective order that fluent English speakers follow without quite knowing why.

…adjectives in English absolutely have to be in this order: opinion-size-age-shape-colour-origin-material-purpose Noun. So you can have a lovely little old rectangular green French silver whittling knife. But if you mess with that word order in the slightest you’ll sound like a maniac. It’s an odd thing that every English speaker uses that list, but almost none of us could write it out.

The Cambridge Dictionary lists a slightly different order: opinion, size, physical quality, shape, age, colour, origin, material, type, purpose. A poem by Alexandra Teague explores the topic in a creative way:

That summer, she had a student who was obsessed

with the order of adjectives. A soldier in the South

Vietnamese army, he had been taken prisoner when

Saigon fell. He wanted to know why the order

could not be altered. The sweltering city streets shook

with rockets and helicopters. The city sweltering

streets.

Did anyone learn this in school? I sure didn’t. How do we all know then? My daughter’s kindergarten teacher had a great phrase she used when things got a bit tricky as her students learned to read: “the English language is a rascal”. (via @MattAndersonBBC)

Update: Language Log’s post on adjective order is worth reading. (thx, stephen & margaret)

Frank Ocean dropped his long-awaited album the other day and to go along with it, he gave away a magazine called Boys Don’t Cry for free at four pop-up locations in LA, NYC, Chicago, and London. Kanye West contributed to the album and magazine, penning a poem about McDonald’s for the latter. Here’s the poem:

McDonald’s man

McDonald’s man

The French fries had a plan

The French fries had a plan

The salad bar and the ketchup made a band

Cus the French Fries had a plan

The French fries had a plan

McDonald’s man

McDonald’s

I know them French fries have a plan

I know them French fries have a plan

The cheeseburger and the shakes formed a band

To overthrow the French fries plan

I always knew them French fries was evil man

Smelling all good and shit

I don’t trust no food that smells that good man

I don’t trust it

I just can’t

McDonald’s man

McDonald’s man

McDonald’s, man

Them French fries look good tho

I knew the Diet Coke was jealous of the fries

I knew the McNuggets was jealous of the fries

Even the McRib was jealous of the fries

I could see it through his artificial meat eyes

And he only be there some of the time

Everybody was jealous of them French fries

Except for that one special guy

That smooth apple pie

Man, I can’t help but like Kanye. Just when you think he takes himself way too seriously, he does something like this and you can’t tell if he’s taking himself way WAY too seriously or not seriously at all. McDonald’s, man. Kanye drawing courtesy of Chris Piascik. (via @gavinpurcell)

From 1971, here’s Jesse Jackson on Sesame Street doing a call-and-response with the children of the poem I Am - Somebody.

I Am

Somebody

I Am

Somebody

I May Be Poor

But I Am

Somebody

I May Be Young

But I Am

Somebody

I May Be On Welfare

But I Am

Somebody

It’s difficult to imagine something like this airing on the show now. Sesame Street was originally designed to serve the needs of children in low-income homes, but now the newest episodes of the show air first on HBO…a trickle-down educational experience. (via @kathrynyu)

A new commercial from Apple pairs photos & videos shot on iPhone 6 with a poem from Maya Angelou called Human Family.

We seek success in Finland,

are born and die in Maine.

In minor ways we differ,

in major we’re the same.

I note the obvious differences

between each sort and type,

but we are more alike, my friends,

than we are unalike.

We are more alike, my friends,

than we are unalike.

We are more alike, my friends,

than we are unalike.

You can hear Angelou recite the entire poem here:

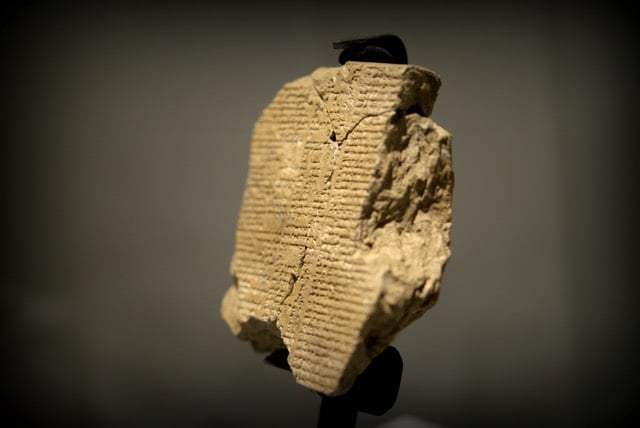

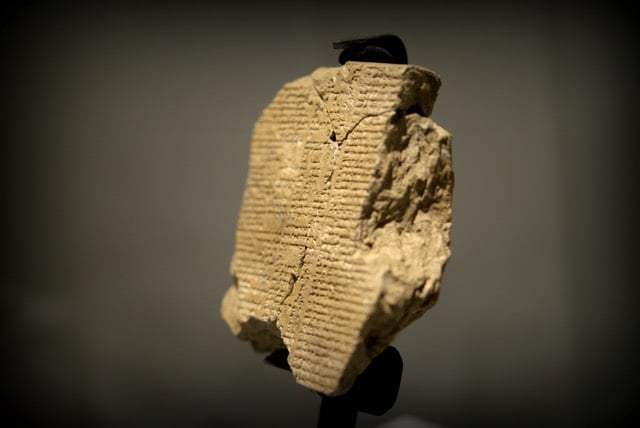

The Epic of Gilgamesh just got more epic. A recent find of a stone tablet dating back to the neo-Babylonian period (2000-1500 BCE) has added 20 new lines to the ancient Mesopotamian poem.

The tablet adds new verses to the story of how Gilgamesh and Enkidu slew the forest demigod Humbaba. Gilgamesh, King of Uruk, gets the idea to kill the giant Humbaba, guardian of the Cedar Forest, home of the gods, in Tablet II. He thinks accomplishing such a feat of strength will gain him eternal fame. His wise companion (and former wild man) Enkidu tries to talk him out of it — Humbaba was set to his task by the god Enlil — but stubborn Gilgamesh won’t budge, so Enkidu agrees to go with him on this quest. Together they overpower the giant. When the defeated Humbaba begs for mercy, offering to serve Gilgamesh forever and give him every sacred tree in the forest, Gilgamesh is moved to pity, but Enkidu’s blood is up now and he exhorts his friend to go through with the original plan to kill the giant and get that eternal renown he craves. Gilgamesh cuts Humbaba’s head off and then cuts down the sacred forest. The companions return to Uruk with the trophy head and lots of aromatic timber.

How the tablet was discovered is notable as well. Since 2011, the Sulaymaniyah Museum in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq was been paying smugglers to intercept artifacts leaving the country, no questions asked. The tablet was likely illegally excavated from the southern part of Iraq, and the museum paid the seller of this particular tablet $800 to keep it in the country.

This is glorious: an erotic poem by Chris Plante constructed from snippets of iPhone 6 reviews.

I have really big hands

Would be an understatement.

This is quite helpful.

When the tips of your fingers are grasping on for dear life,

Your fingers need to secure a firm grip.

I can still wrap my fingers around

Well…

More of everything.

No lines from John Gruber’s review, but Linus Edwards made a short poem just from that one:

Makes itself felt in your pants pocket.

Ah, but then there’s The Bulge.

I definitely appreciate the stronger vibrator.

(via @sippey)

Black Perl is a poem written in valid Perl 3 code:

BEFOREHAND: close door, each window & exit; wait until time.

open spellbook, study, read (scan, select, tell us);

write it, print the hex while each watches,

reverse its length, write again;

kill spiders, pop them, chop, split, kill them.

unlink arms, shift, wait & listen (listening, wait),

sort the flock (then, warn the "goats" & kill the "sheep");

kill them, dump qualms, shift moralities,

values aside, each one;

die sheep! die to reverse the system

you accept (reject, respect);

next step,

kill the next sacrifice, each sacrifice,

wait, redo ritual until "all the spirits are pleased";

do it ("as they say").

do it(*everyone***must***participate***in***forbidden**s*e*x*).

return last victim; package body;

exit crypt (time, times & "half a time") & close it,

select (quickly) & warn your next victim;

AFTERWORDS: tell nobody.

wait, wait until time;

wait until next year, next decade;

sleep, sleep, die yourself,

die at last

# Larry Wall

It’s not Shakespeare, but it’s not bad for executable code.

Irish poet Seamus Heaney has died at 74. The Guardian has a brief account of his life; The Telegraph grapples more directly with the work There’s also his long, insightful interview with The Paris Review, from 1997.

.

“Heaney’s volumes make up two-thirds of the sales of living poets in Britain,” the BBC wrote in 2007, calling him “arguably, the English language’s greatest living bard.”

One of his best-known poems, “Digging,” compares his trade to that of his father and grandfather, who were farmers and cattle-raisers. These are its last two stanzas:

The cold smell of potato mould, the squelch and slap

Of soggy peat, the curt cuts of an edge

Through living roots awaken in my head.

But I’ve no spade to follow men like them.

Between my finger and my thumb

The squat pen rests.

I’ll dig with it.

One of Heaney’s great later achievements was his translation of Beowulf, which I bought and read along with his Selected Poems when I was in college.

Heaney’s take on the Anglo-Saxon most reminds me of the first of Ezra Pound’s Cantos, a weird mix of old epic and contemporary free-verse imagery and meters, a translation of a translation of Homer that begins “And then” and ends “So that:”

When Swinburne died, W.B. Yeats is said to have told his sister, “Now I am King of the Cats.” When Robert Frost died, John Berryman asked, “who’s number one?”

I note this not to pose the question “who’s number one?” now that Heaney has died, but to observe that just as champion boxers and sprinters often have outsized competitive personalities that seem like caricatures compared to other athletes, even among writers, and even when they resist, as Heaney did, being drawn into literary feuds or political debate, great poets are often magnificent and terrible and troubling and glorious and weird.

One thing I will be doing from time to time this week is pulling down random books from my shelves and writing about them, under the belief that the internet is better when not all of it comes from the internet. Here’s the second installment (you can read the first here).

One of my favorite writers, poets, and teachers is Susan Stewart. She’s just one of those people who radiates intelligence and fun.

She also helped show me that you could put both of these things into critical writing — that plain, everyday language and willfully studied, obscure language were both traps.

Here is an audio recording of her reading one of my favorite of her poems, “Apple,” which begins:

If I could come back from the dead, I would come back

for an apple, and just for the first bite, the first

break, and the cold sweet grain

against the roof of the mouth, as plain

and clear as water.

This poem also includes a Twitter-worthy quip: “If an apple’s called ‘delicious,’ it’s not.”

And here is an excerpt from one of my favorite of her books (which I’m pretty sure was originally actually her doctoral thesis), On Longing: Narratives of the Miniature, the Gigantic, the Souvenir, the Collection:

Problems of the inanimate and the animate here bring us to a consideration of the toy. The toy is the physical embodiment of the fiction: it is a device for fantasy, a point of beginning for narrative. The toy opens an interior world, lending itself to fantasy and privacy in a way that the abstract space, the playground, of social play does not. To toy with something is to manipulate it, to try it out within sets of contexts, none of which is determinative… The desire to animate the toy is the desire not simply to know everything but also to experience everything simultaneously…

Here is the dream of the impeccable robot that has haunted the West at least since the advent of the industrial revolution. The eighteenth and nineteenth centuries mark the heyday of the automaton, just as they mark the mechanization of labor: jigging Irishmen, whistling birds, clocks with bleating sheep, and growling dogs guarding baskets of fruit. The theme of death and irreversibility reappears in the ambivalent status of toys like the little guillotines that were sold in France during the time of the Revolution. In 1793 Goethe wrote to his mother in Frankfurt requesting that she buy a toy guillotine for his son, August. This was a request she refused, saying that the toy’s maker should be put in stocks.

Such automated toys find their strongest modern successors in “models” of ships, trains, airplanes, and automobiles, models of the products of mechanized labor. These toys are nostalgic in a fundamental sense, for they completely transform the mode of production of the original as they miniaturize it: they produce a representation of a product of alienated labor, a representation which itself is constructed by artisanal labor. The triumph of the model-maker is that he or she has produced the object completely by hand, from the beginning assembly to the “finishing touches.”

It’s a kind of writing that’s totally within the boundaries of the historical and theoretical conventions of the academy, but is also always rhetorically and imaginatively precise and correct, from the individual syllable to the grouped processions of images.

I can’t tell you how rare that is. Probably you know already.

One thing I will be doing from time to time this week is pulling down random books from my shelves and writing about them, under the belief that the internet is better when not all of it comes from the internet. Here’s the first installment.

According to tradition, Simonides of Keos was the first Greek poet who composed and sung poems for money, rather than being kept by a patron. He was also famously stingy and liked to pose riddles:

They say that Simonides had two boxes, one for favors, the other for fees. So when someone came to him asking for a favor he had the boxes displayed and opened: the one was found to be empty of graces, the other full of money. And that’s the way Simonides got rid of a person requesting a gift.

Simonides’s world was one where old relationships of gift-exchange and patronage were breaking down in favor of what for Greeks was a fairly new invention, coinage. And all of his poetry and the stories around him seem to play with this: how the old world mythic heroes and Gods (Homer’s subjects) gave way to Olympic champions and rich merchants (Simonides’s subjects), the way value can be real but invisible, how words can be things that you exchange, like gifts or cash. This is one thing that helps make Simonides unusually modern.

That, at least, is poet/critic Anne Carson’s take in her terrific book Economy of the Unlost, which juxtaposes Simonides and the equally staggering twentieth-century poet Paul Celan:

Simonides of Keos was the smartest person in the fifth century B.C., or so I have come to believe. History has it that he was also the stingiest. Fantastical in its anecdoes, undeniable in its implications, the stinginess of Simonides can tell us something about the moral life of a user of money and something about the poetic life of an economy of loss.

No one who uses money is unchanged by that.

No one who uses money can easily get a look at their own practice. Ask eye to see its own eyelashes, as the Chinese proverb says. Yet Simonides did so, not only because he was smart.

Another argument Carson makes is that because Simonides was willing to write for anyone who would pay, his epigraphs — literally, writing that would be inscribed on a gravestone — is the “first poetry in the ancient Greek tradition about which we can certainly say, these are texts written to be read: literature” (emphasis mine).

I always liked the way poet Frank O’Hara walked up to the manifesto:

Everything is in the poems, but at the risk of sounding like the poor wealthy man’s Allen Ginsberg I will write to you because I just heard that one of my fellow poets thinks that a poem of mine that can’t be got at one reading is because I was confused too. Now, come on. I don’t believe in god, so I don’t have to make elaborately sounded structures. I hate Vachel Lindsay, always have; I don’t even like rhythm, assonance, all that stuff. You just go on your nerve. If someone’s chasing you down the street with a knife you just run, you don’t turn around and shout, “Give it up! I was a track star for Mineola Prep.”

But what do we call it, Frank? We need a name.

Personism, a movement which I recently founded and which nobody knows about… was founded by me after lunch with LeRoi Jones on August 27, 1959, a day in which I was in love with someone (not Roi, by the way, a blond). I went back to work and wrote a poem for this person. While I was writing it I was realizing that if I wanted to I could use the telephone instead of writing the poem, and so Personism was born. It’s a very exciting movement which will undoubtedly have lots of adherents. It puts the poem squarely between the poet and the person, Lucky Pierre style, and the poem is correspondingly gratified. The poem is at last between two persons instead of two pages. In all modesty, I confess that it may be the death of literature as we know it. While I have certain regrets, I am still glad I got there before Alain Robbe-Grillet did. Poetry being quicker and surer than prose, it is only just that poetry finish literature off.

LeRoi Jones eventually changed his name to Amiri Baraka. Alain Robbe-Grillet was an proto-postmodern French novelist associated with the nouveau roman, or “new novel.” It’s probably better if I let you figure out what a Lucky Pierre is for yourself.

Because O’Hara dated his poems, we know what poem he wrote between lunch with Jones and picking up the telephone; appropriately, it’s called “personal poem”:

Now when I walk around at lunchtime

I have only two charms in my pocket

an old Roman coin Mike Kanemitsu gave me

and a bolt-head that broke off a packing case

when I was in Madrid the others never

brought me too much luck though they did

help keep me in New York against coercion

but now I’m happy for a time and interested

I walk through the luminous humidity

passing the House of Seagram with its wet

and its loungers and the construction to

the left that closed the sidewalk if

I ever get to be a construction worker

I’d like to have a silver hat please

and get to Moriarty’s when I wait for

LeRol and hear who wants to be a mover and

shaker the last five years my batting average

is .016 that’s that, and LeRol comes in

and tells me Miles Davis was clubbed 12

times last night outside BIRDLAND by a cop

a lady asks us for a nickel for a terrible

disease but we don’t give her one we

don’t like terrible diseases, then

we go eat some fish and some ale it’s

cool but crowded we don’t like Lionel Trilling

we decide, we like Don Allen we don’t like

Henry James so much we like Herman Melville

we don’t want to be in the poet’s walk in

San Francisco even we just want to be rich

and walk on girders in our silver hats

I wonder if one person out of the 8,000,000 is

thinking of me as I shake hands with LeRol

and buy a strap for my wristwatch and go

back to work happy at the thought possibly so

Here is a photo of Davis after being beaten:

One reason Davis’s assault and arrest alarmed O’Hara as much as it did was the increasing police violence at bars and clubs where gay men gathered — which culminated in the Stonewall Riots, five years after his accidental death in 1964.

O’Hara’s poetry got a boost in sales and pop-culture recognition recently, when it was prominently featured in the Season Two premiere of Mad Men. Don Draper reads from Meditations In An Emergency’s “Mayakovsky”:

Now I am quietly waiting for

the catastrophe of my personality

to seem beautiful again,

and interesting, and modern.

The country is grey and

brown and white in trees,

snows and skies of laughter

always diminishing, less funny

not just darker, not just grey.

It may be the coldest day of

the year, what does he think of

that? I mean, what do I? And if I do,

perhaps I am myself again.

I don’t know why I always think of this mode of literature in terms of media history. Maybe that’s just the way I think. Or it’s O’Hara picking up the telephone, that black-and-white photo of Davis’s blood-spattered suit, Don Draper dropping his copy of a book into a suburban corner mailbox.

Elsewhere in Personism, O’Hara says, “Nobody should experience anything they don’t need to, if they don’t need poetry bully for them. I like the movies too. And after all, only Whitman and Crane and Williams, of the American poets, are better than the movies.” Maybe if he were writing today, he might say, “only ___ and ___ and ___ are better than playing video games.”

His poem “Lines for the Fortune Cookies” shows O’Hara would have completely understood (and ruled at) Twitter. Here are just three samples (all well under the character limit):

- Your walk has a musical quality which will bring you fame and fortune.

- You may be a hit uptown, but downtown you’re legendary!

- You are a prisoner in a croissant factory and you love it.

How do Tennyson, Longfellow, and Thoreau stack up in terms of the thickness of their beards? Surprisingly, that question has been asked and answered.

That “exalted dignity, that certain solemnity of mien,” lent by an imposing beard, “regardless of passing vogues and sartorial vagaries,” says Underwood, is invariably attributable to the presence of an obscure principle known as the odylic force, a mysterious product of “the hidden laws of nature.” The odylic, or od, force is conveyed through the human organism by means of “nervous fluid” which invests the beard of a noble poet with noetic emanations and ensheathes it in an ectoplasmic aura.

(via stamen)

Poet Christian Bök wants to compose a poem and encode it into the DNA of the Deinococcus radiodurans bacteria — “the most radiation-resistant organism known”.

He wants to inject the DNA with a string of nucleotides that form a comprehensible poem, and he also wants the protein that the cell produces in response to form a second comprehensible poem.

AGGCGT GCCACC AAT

TCT TACC GATTT CT

CA CTCTAG ACC CTG

AGCCCA CGC GGTTCA

(via mr)

At the newly renovated Bygone Bureau, Darryl Campbell investigates the small but vibrant poetry community that has formed in the comment threads on the NY Times website.

Tiger, Tiger burning bright

In the sex clubs of Orlando

Guess it’s time you took a break

And lived life with more candor

Must’ve been weird, your secret life

Never an unserviced erection

Shouldn’t you, though, have taught the wife

Some proper club selection?

This is a 36-second wax cylinder recording of Walt Whitman reading a few lines from his poem, America. You may recognize the recording from its use in Levi’s new ad campaign:

I thought for sure that Ryan McGinley had directed this and the O Pioneers! commercial but it turns out he just (just!) did the photos for the print campaign. (via slate)

Update: The audio clip used in that commercial might not be Whitman after all. From the inbox:

The Walt Whitman recording that is being used by the Levi’s commercial that you posted on the 28th is actually not Whitman, and is now considered by most audio archivists to be a hoax.

More information about this most interesting recording can be found in Vol. X, No. 3 of Allen Koenigsberg’s Antique Phonograph Monthly magazine from 1992, pages 9-11.

Among things pointed out, one is that the speech on the soundtrack ends with the quote, “Freedom Law and Love,” whereas the original printed version of the poem ends with “Chair’d in the adamant of Time.”

Koenigsberg also points out that Whitman’s last years were chronicled on a daily basis by his personal secretary, and being wheelchair-bound, such a visit for Whitman would have been difficult, unprecedented, and undoubtedly noted.

(thx, jack)

Flarf is a form of poetry made by combining together phrases from random web searches. Here’s an early example:

“Yeah, mm-hmm, it’s true

big birds make

big doo! I got fire inside

my ‘huppa’-chimp(TM)

gonna be agreessive, greasy aw yeah god

wanna DOOT! DOOT!

Pffffffffffffffffffffffffft! hey!”

Flarf started off as a joke but then these joke poems that people were coming up with “evolved from ‘bad’ to ‘sort of great’”.

Edge Books publisher Rod Smith, a poet himself, says he feels the [Flarf] collective is prompting a bit of anarchy in the poetry world by widening the vocabulary of what is permissible. “Aesthetic judgments about what’s bad in a very hierarchal society are usually serving upper-class people with a certain amount of privilege,” he says. “So for a bunch of poets who are very well schooled in a variety of traditions of American poetry to take what’s considered bad and throw that at people is a very interesting maneuver. It’s not simply bad poetry; it’s quote-unquote bad poetry written by people who know how to write poetry.”

Hackers Can Sidejack Cookies, a poem by Heather McHugh.

Designs succumbing

to creeping featuritis

are banana problems.

(“I know how to spell banana,

but I don’t know when to stop.”)

I can’t decide if this is creepy or cool: a bunch of videos of dead poets reading their poems. The effect is achieved by warping photos to make it look like their mouths are moving. Here’s Poe reading The Raven and Robert Frost doing The Road Not Taken.

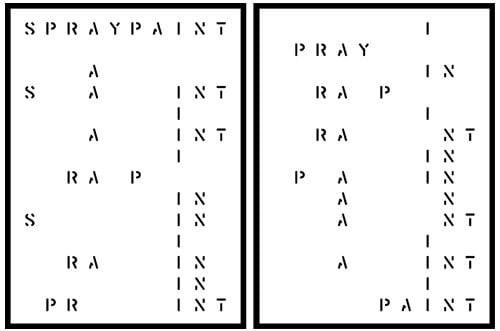

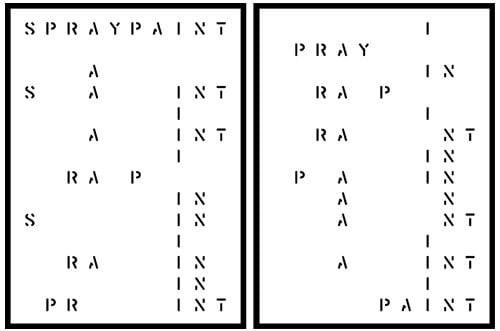

Inspired by Emmett Williams, a practitioner of concrete poetry, Rob Giampietro has written three poems: Wastebasket, Snowflakes, and Spraypaint.

Giampietro has put out a call for someone to develop a Williams Word Generator. Drop him a line if you can help out…shouldn’t be too much different than the many “words within words” generators scattered around the web.

A poem in which each instance of the word “love” is replaced by “Boston Red Sox Hall of Fame Catcher Carlton Fisk”.

“And know you not,” says Boston Red Sox Hall of Fame Catcher Carlton Fisk, “who bore the blame?”

“My dear, then I will serve.”

(via hodgman)

Austin Kleon makes Newspaper Blackout Poems by blacking out all but a few choice words of newspaper articles.

A Woman’s bust is the host of Romance, so Don’t deplore my fondness for It

The One Day Poem Pavilion uses the sun to display a poem one line at a time over the course of an entire day. (via stingy kids)

The Virginia Quarterly Review analyzed their poetry submissions for use of poetic cliches and found that the cliches do get published more often than not. Also of note is that “darkness” is an undervalued poetic cliche…it was in only 4% of submitted poems but in 17% of published poems. Poets, “darkness” is your way into VQR.

I’ve gotten totally re-obsessed with Kathy Acker, the East Village writer who died in 1997. It started with this recording of Acker reading a poem [Warning: audio, 2 minutes, 28 seconds, and not really safe for work!] that was released in 1980 on the LP “Sugar, Alcohol & Meat” by Giorno Poetry Systems and recently digitized by UbuWeb. Her New York accent is one that has largely disappeared since; she sounds amazing. Then I found this, which is an incredibly long mp3, the first 3/4s of which is a Michael Brownstein reading. The end, though, is a monologue which then becomes a stageplay by Acker about a woman, her suicide, her grandmother, and her psychiatrist. It is absolutely not safe for work, what with its endless use of a certain word for ladyparts that goes over well in Scotland but not at all (yet!) in the U.S.

Winners of the Helvetica haiku contest I pointed to a couple of weeks ago. My favorite of all the ones listed: “i shot the serif / left him there full of leading / yearning for kerning”. Close second: “She misunderstood / When I said she was ‘Grotesque’ / Akzidenz happen”. I am a sucker for puns.

What would happen if poets and playwrights wrote works whose titles were anagrams of their names? Here’s one by Basho called Has B.O: “Swamp mist, eyes water- / Why is that monk still wearing / Winter robes in June?”

Newer posts

Older posts

Socials & More