kottke.org posts about infoviz

Using NASA’s GISTEMP data (a measure of the surface air temperature around the world), climate researcher Antti Lipponen put together this data visualization of global temperature anomalies from 1900-2016. Until about the mid-90s, the lines in different parts of the world pulse blue (cooler) or yellow/red (warmer) each year as regional climate varies…but it slowly turns less blue and more yellow. From 1997 on, the thing is basically an angry red porcupine.

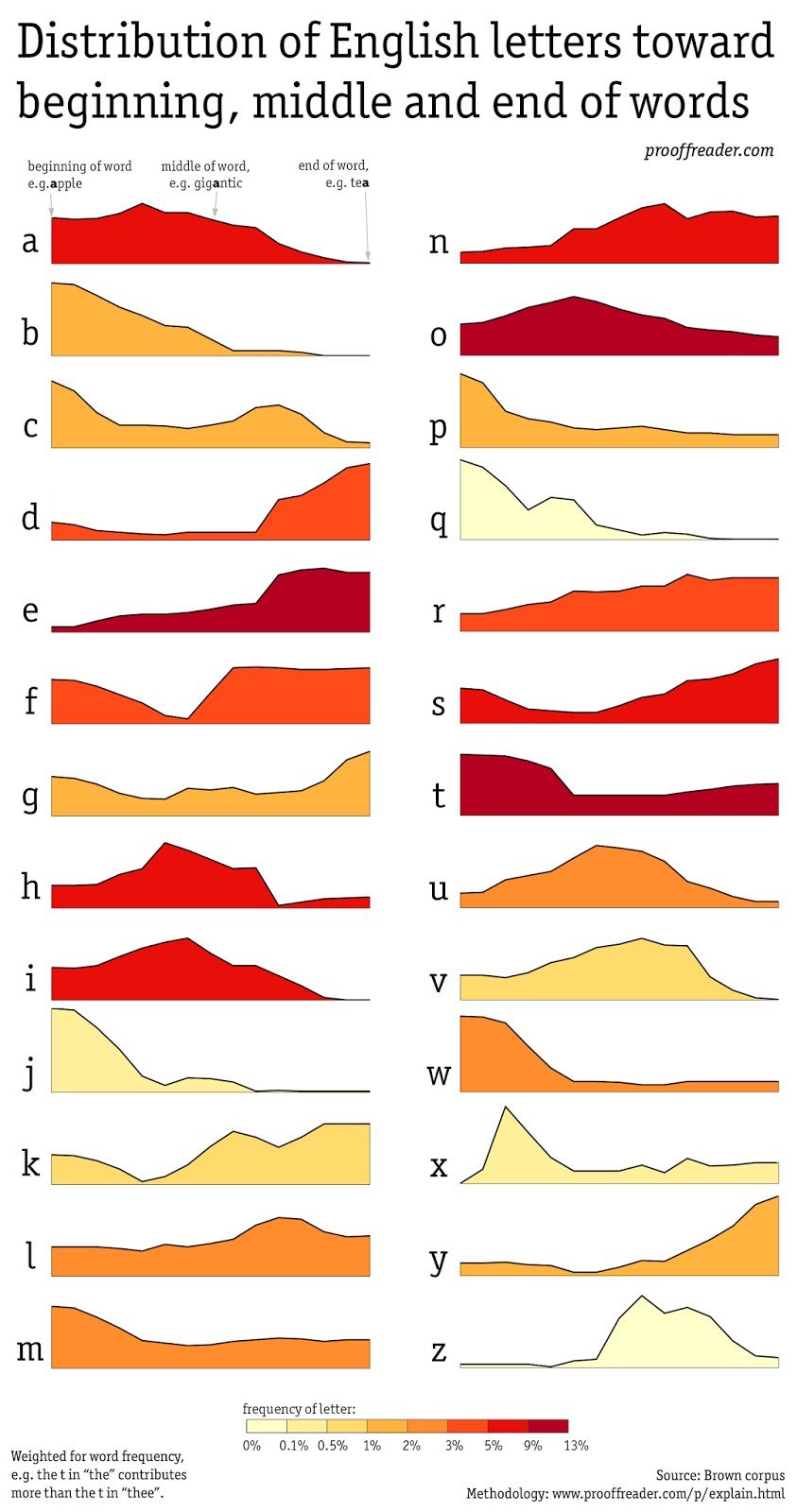

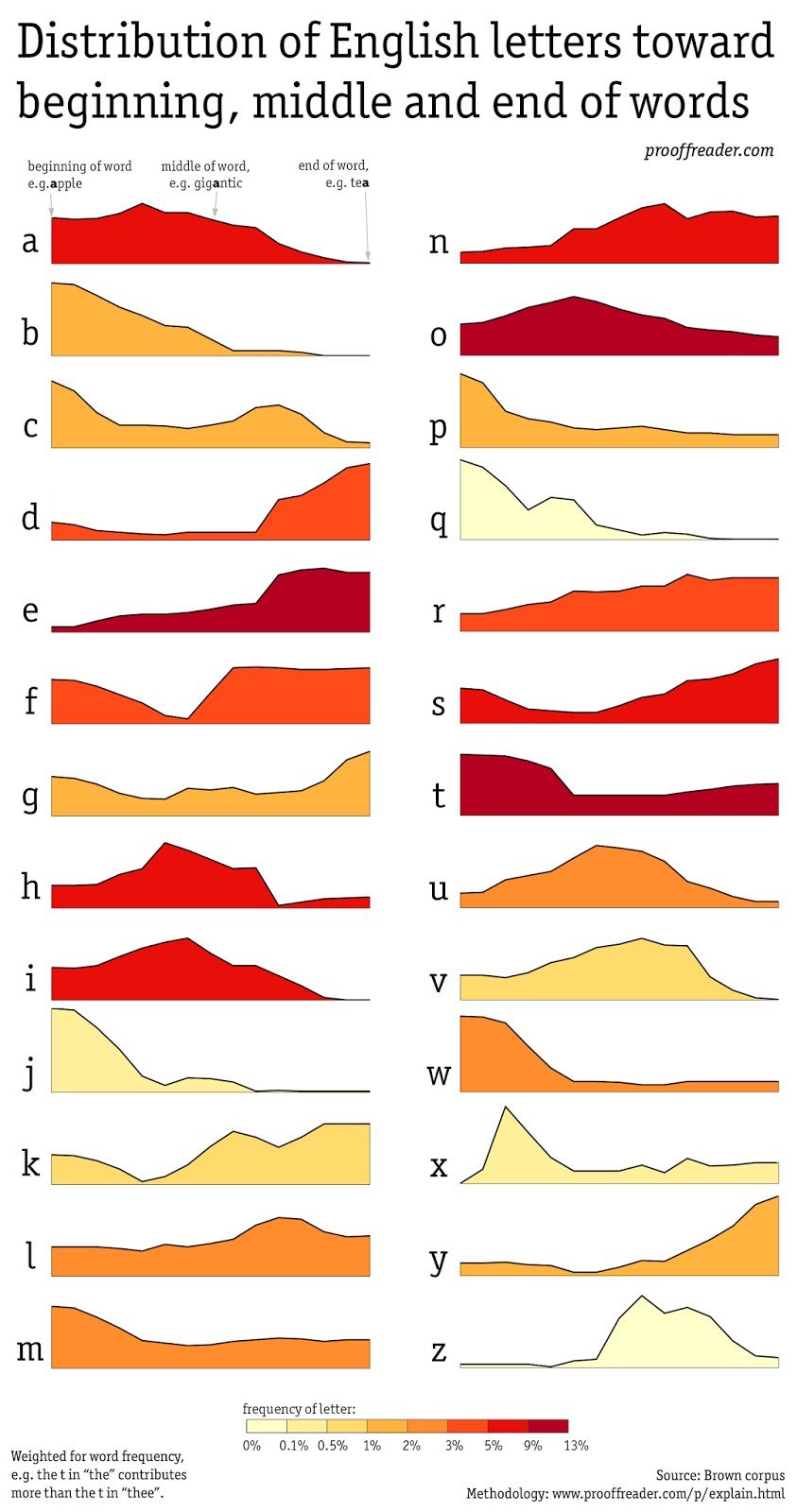

David Taylor analyzed a corpus of English words to see where each letter of the alphabet fell and graphed the results.

No surprise that “q” and “j” are found mostly at the beginnings of words and “y” and “d” at the ends. More interesting are the few letters with more even distribution throughout words, like “l”, “r”, and even “o”. Note that this analysis is based on a corpus of words in use, not on a dictionary:

I used a corpus rather than a dictionary so that the visualization would be weighted towards true usage. In other words, the most common word in English, “the” influences the graphs far more than, for example, “theocratic”.

Taylor explained his methodology in a second geekier post. (via @tedgioia)

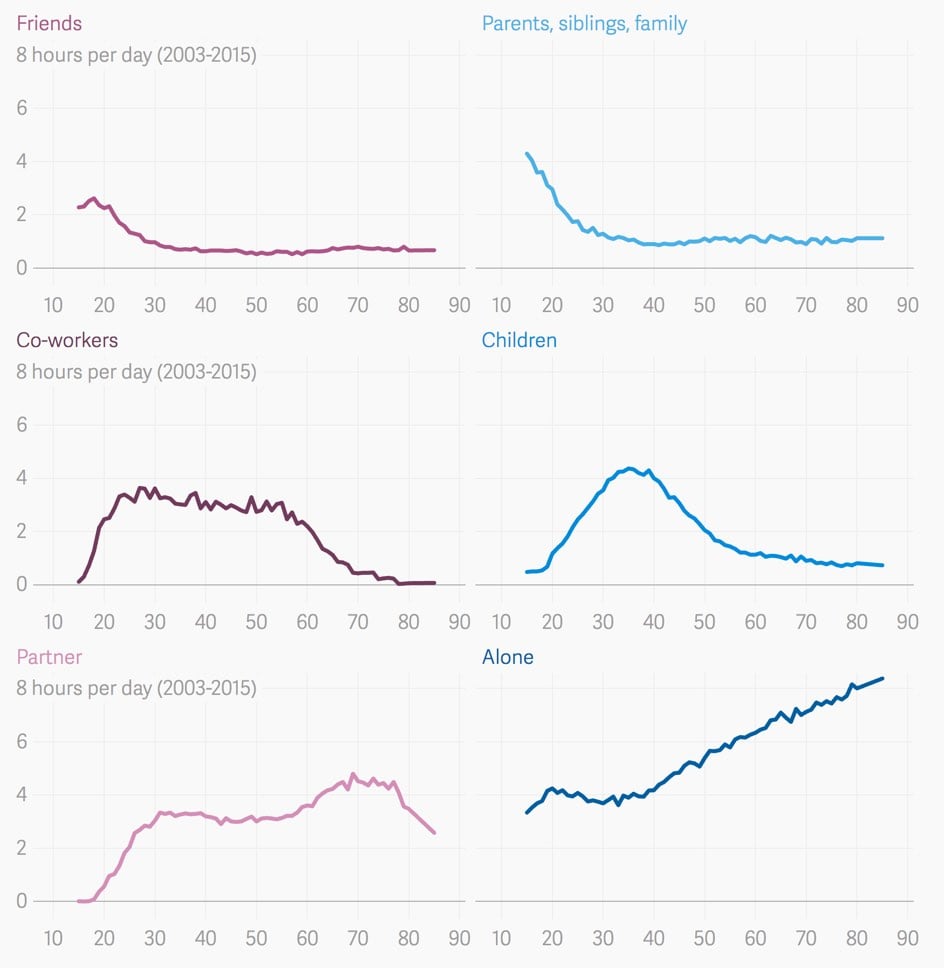

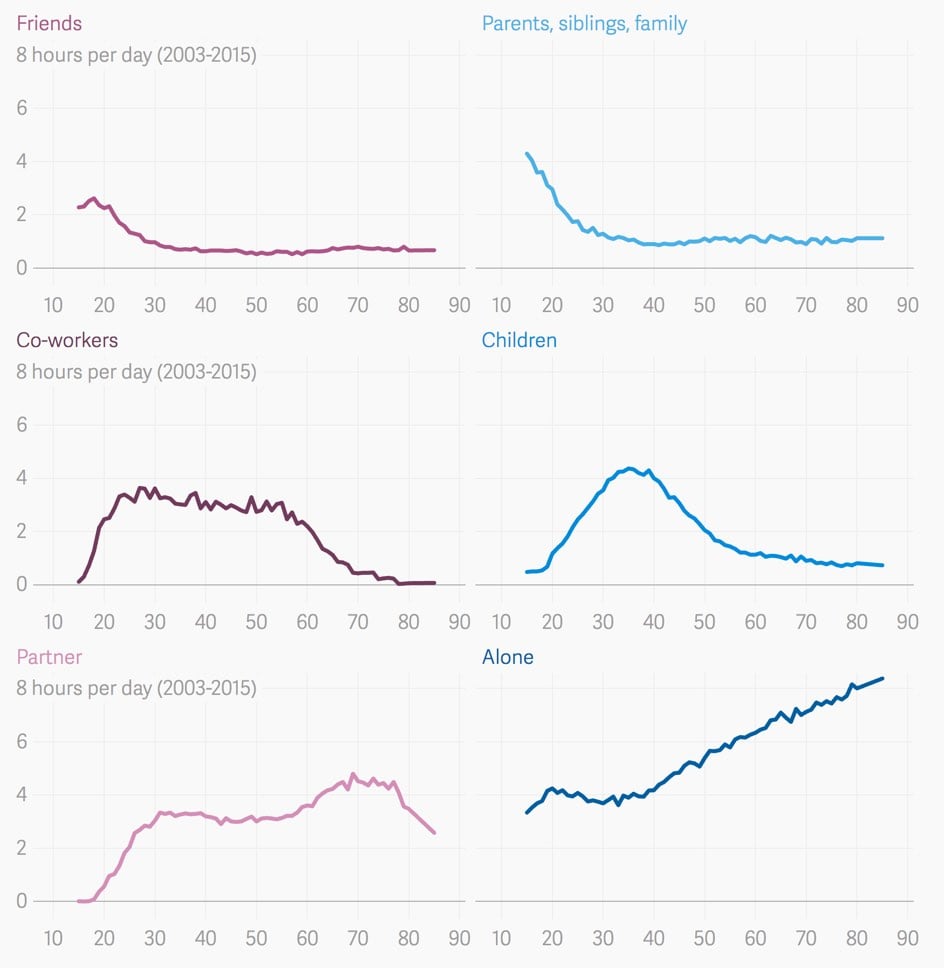

From Quartz, six charts that show who Americans spend their time with.

Some of the relationships Lindberg found are intuitive. Time with friends drops off abruptly in the mid-30s, just as time spent with children peaks. Around the age of 60 — nearing and then entering retirement, for many — people stop hanging out with co-workers as much, and start spending more time with partners.

Others are more surprising. Hours spent in the company of children, friends, and extended family members all plateau by our mid-50s. And from the age of 40 until death, we spend an ever-increasing amount of time alone.

This would make a great book…one chapter about why each chart looks as it does.

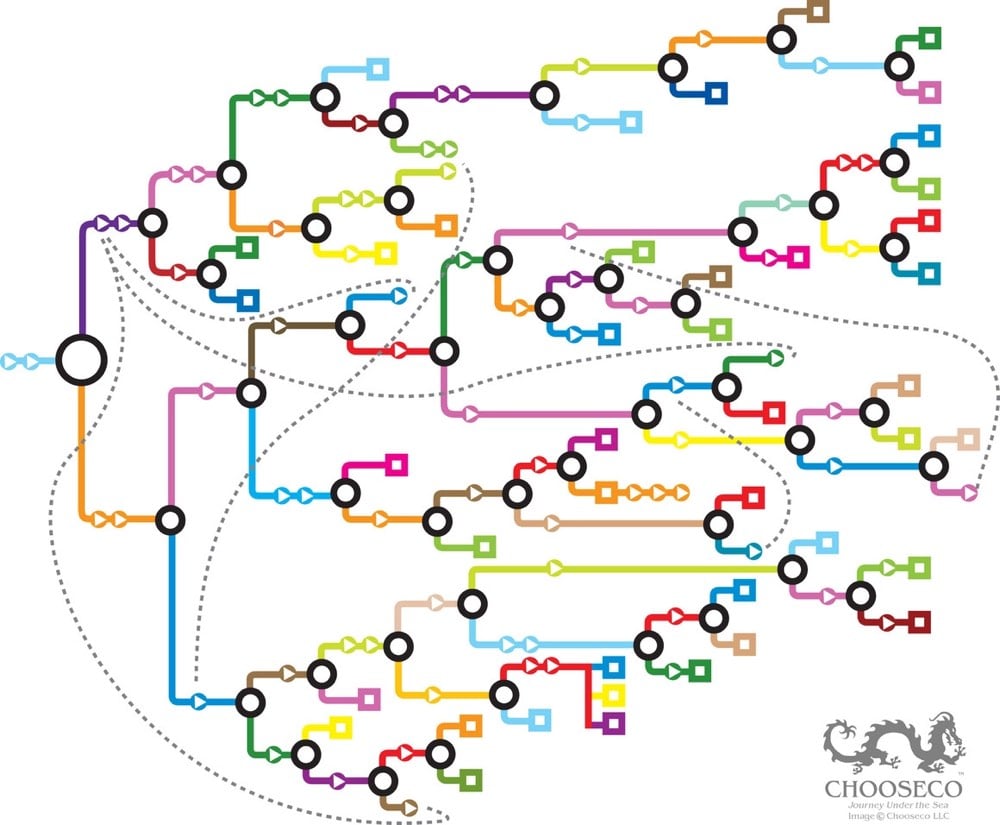

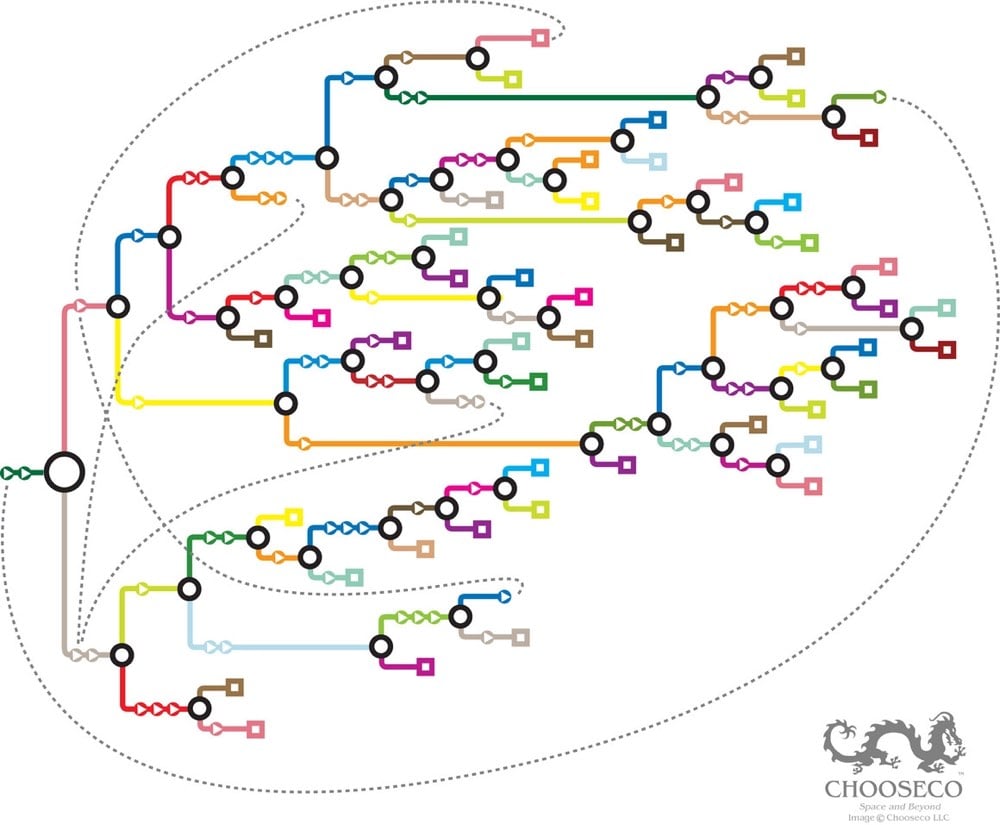

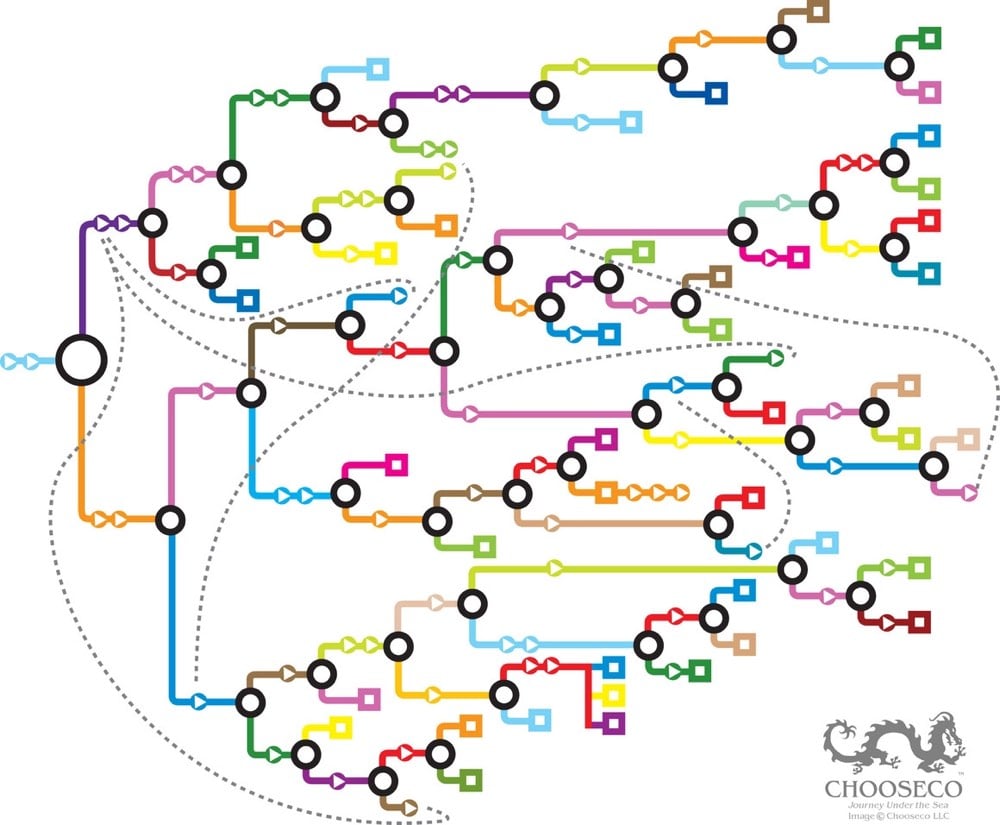

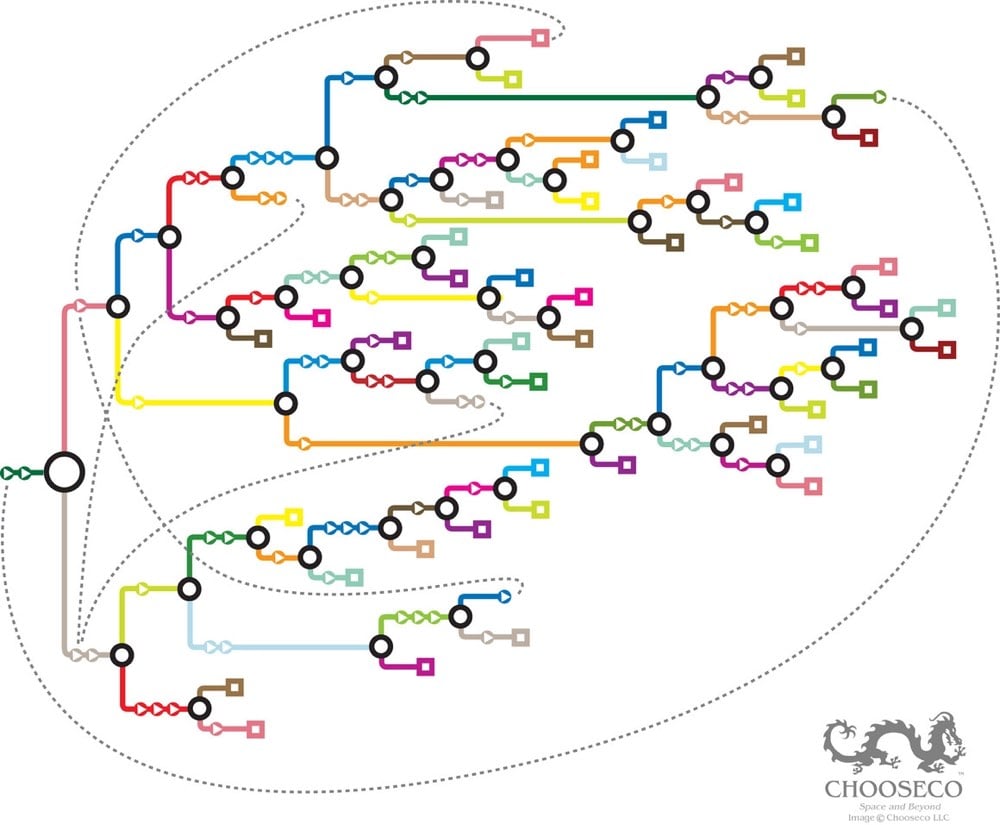

The newest editions of Choose Your Own Adventure books come with maps of the story structure that depicts all the branches, endings, and links of each story.

On the official maps, however, the endings aren’t coded in any way that reveals their nature. Instead, they operate according to a simple key: each arrow represents a page, each circle a choice, and each square an ending. Dotted lines show where branches link to one another.

Mapping the bones of the books can have other purposes, too. Nick Montfort, a poet and professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology who studies interactive fiction, has a habit of asking people what they know about “Choose Your Own Adventure” books. “They often say, ‘You have two choices after every page,’” he says. “That’s not true. Sometimes you have one choice. Sometimes you have more than two. When you show the maps, you can see that these books don’t look exactly the same.”

(via @RLHeppner)

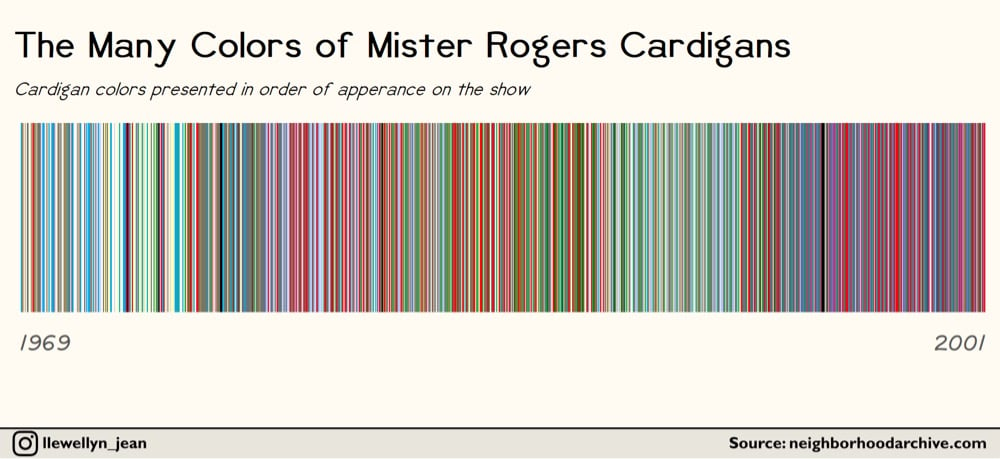

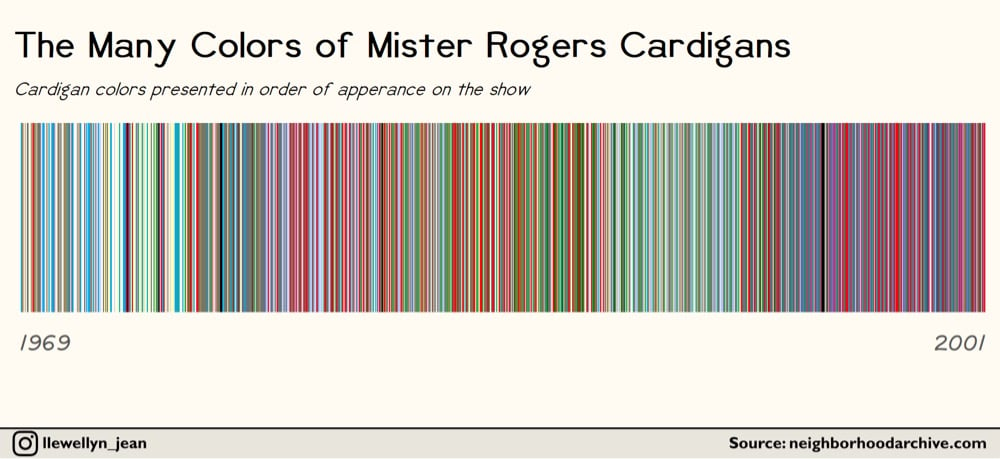

Using data from The Neighborhood Archive, Owen Phillips charted the color of every sweater Mister Rogers wore on his PBS television program from 1979 to 2001.

Some sweaters were worn once and then never again, like the neon blue cardigan Rogers wore in episode 1497. Others, like his harvest gold sweaters, were part of Rogers’ regular rotation and then disappeared. And then there were the unusual batch of black and olive green sweaters Rogers wore exclusively while filming the “Dress-Up” episodes in 1991.

Some things about the sweaters and Mister Rogers:

Update: Phillips updated the chart to include sweater colors all the way back to 1969. (via laura olin)

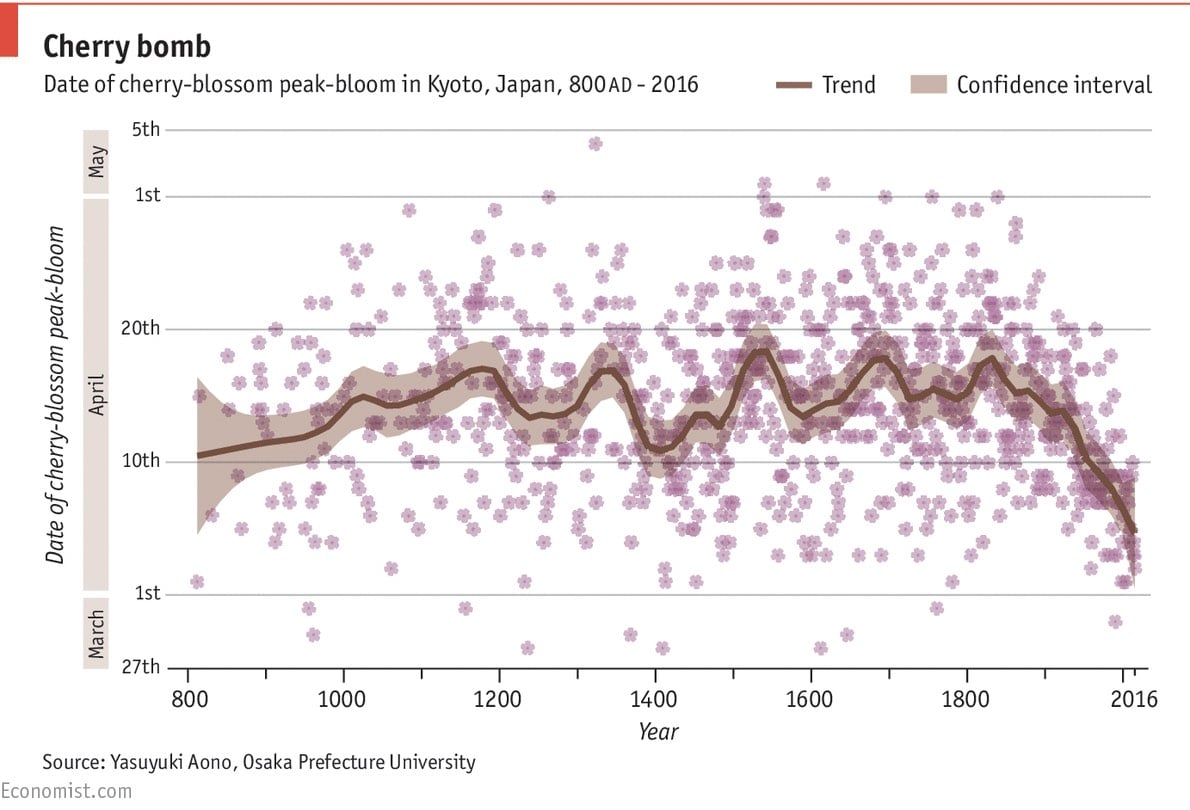

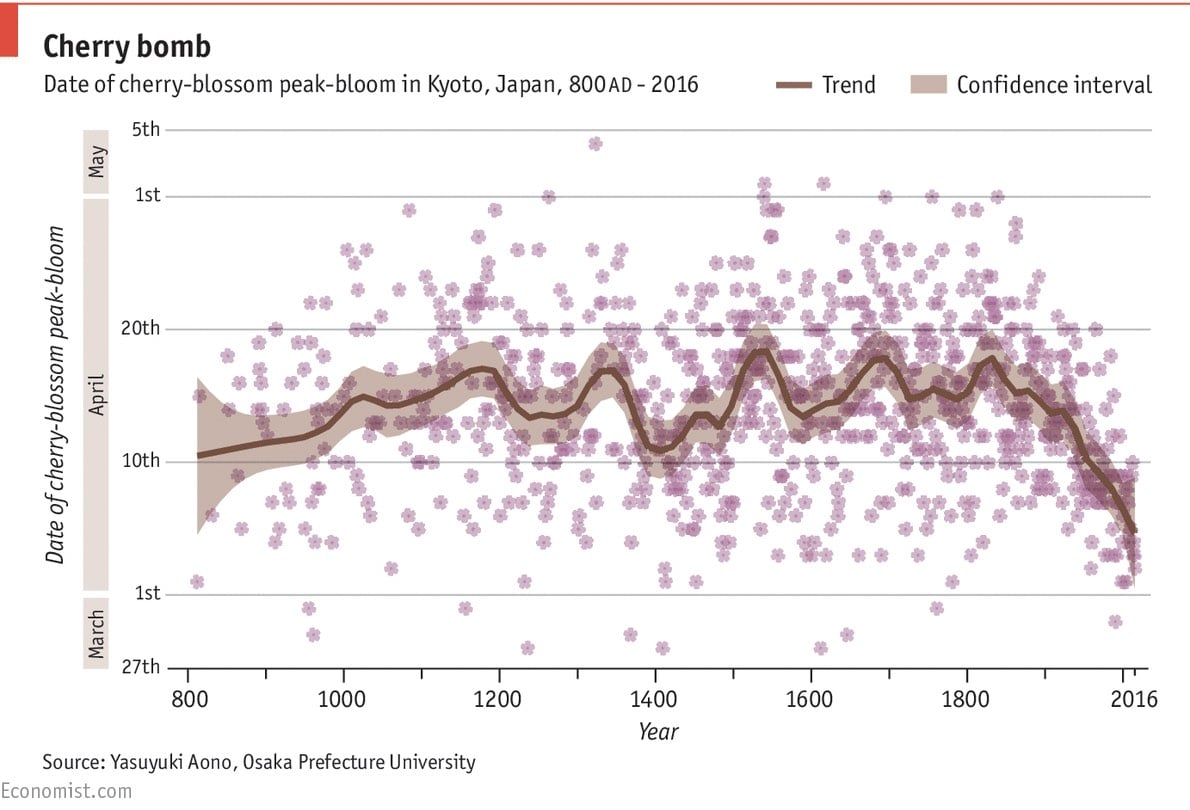

Records of when the cherry blossoms appear in Kyoto date back 1200 years. (Let’s boggle at this fact for a sec…) But as this chart of peak-bloom dates shows, since the most recent peak in 1829, the cherry blossoms have been arriving earlier and earlier in the year.

From its most recent peak in 1829, when full bloom could be expected to come on April 18th, the typical full-flowering date has drifted earlier and earlier. Since 1970, it has usually landed on April 7th. The cause is little mystery. In deciding when to show their shoots, cherry trees rely on temperatures in February and March. Yasuyuki Aono and Keiko Kazui, two Japanese scientists, have demonstrated that the full-blossom date for Kyoto’s cherry trees can predict March temperatures to within 0.1°C. A warmer planet makes for warmer Marches.

Temperature and carbon-related charts like this one are clear portraits of the Industrial Revolution, right up there with oil paintings of the time. I also enjoyed the correction at the bottom of the piece:

An earlier version of this chart depicted cherry blossoms with six petals rather than five. This has been amended. Forgive us this botanical sin.

Gotta remember that flower petals are very often numbered according to the Fibonacci sequence.

From Aron Strandberg,1 this is a timeline visualization of the age of the world’s population from 1960-2060. The world’s human population has increased rapidly in the last couple centuries, most recently doubling since 1970:

A tremendous change occurred with the industrial revolution: whereas it had taken all of human history until around 1800 for world population to reach one billion, the second billion was achieved in only 130 years (1930), the third billion in less than 30 years (1959), the fourth billion in 15 years (1974), and the fifth billion in only 13 years (1987).

But watching that video, you’ll realize that the world’s population will not reach 20 or 30 billion in 2050 — human civilization is getting old.

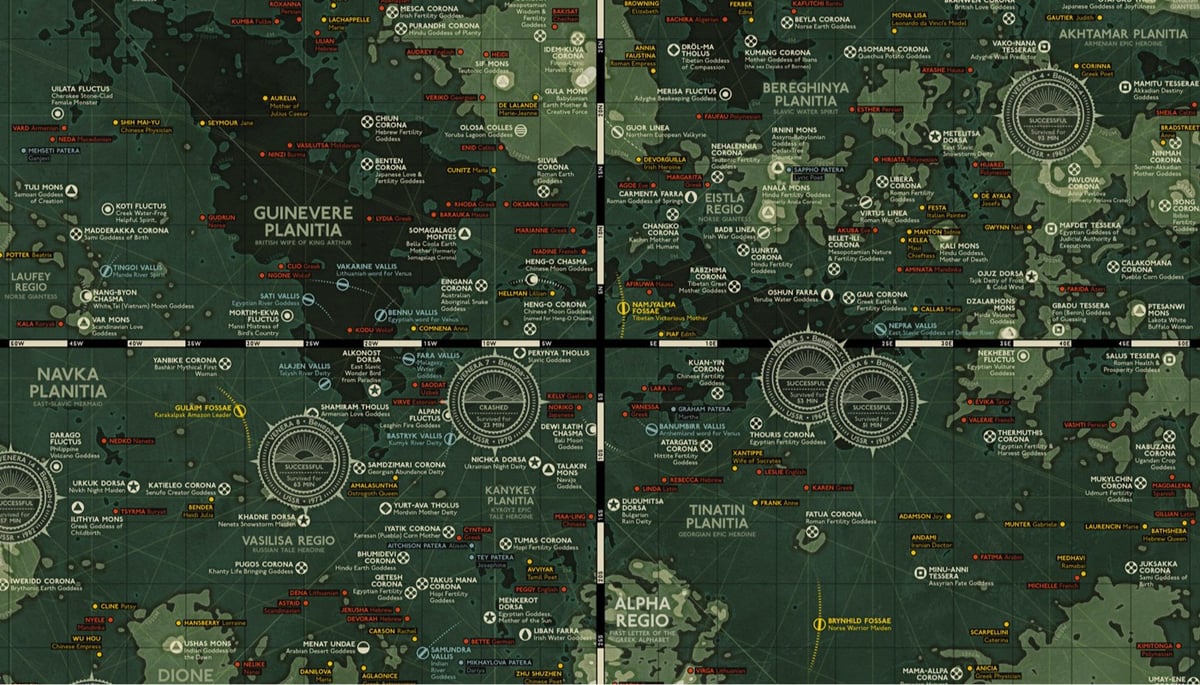

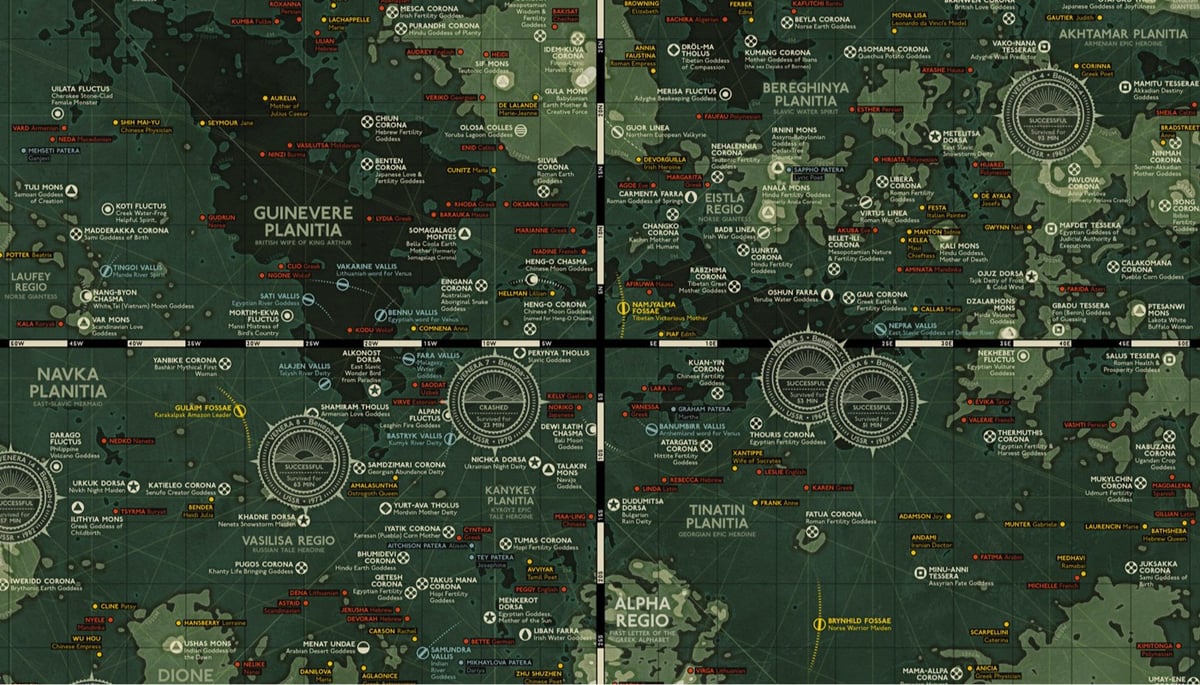

Last year, Eleanor Lutz made a medieval-style map of Mars. As a follow-up, she’s made a topographical map of Venus. The features on Venus are named for female mythological figures & notable women and Lutz provides a small biography for each one on the map. Among those featured on the map are:

Anne Frank

Selu (Cherokee Corn Goddess)

Kali (Hindu Goddess, Mother of Death)

Virginia Woolf

Sedna (Eskimo Whose Fingers Became Seals and Whales)

Ubastet (Egyptian Cat Goddess)

Beatrix Potter

Edith Piaf

Here are the full lists of the craters, mountains, and coronae on Venus.

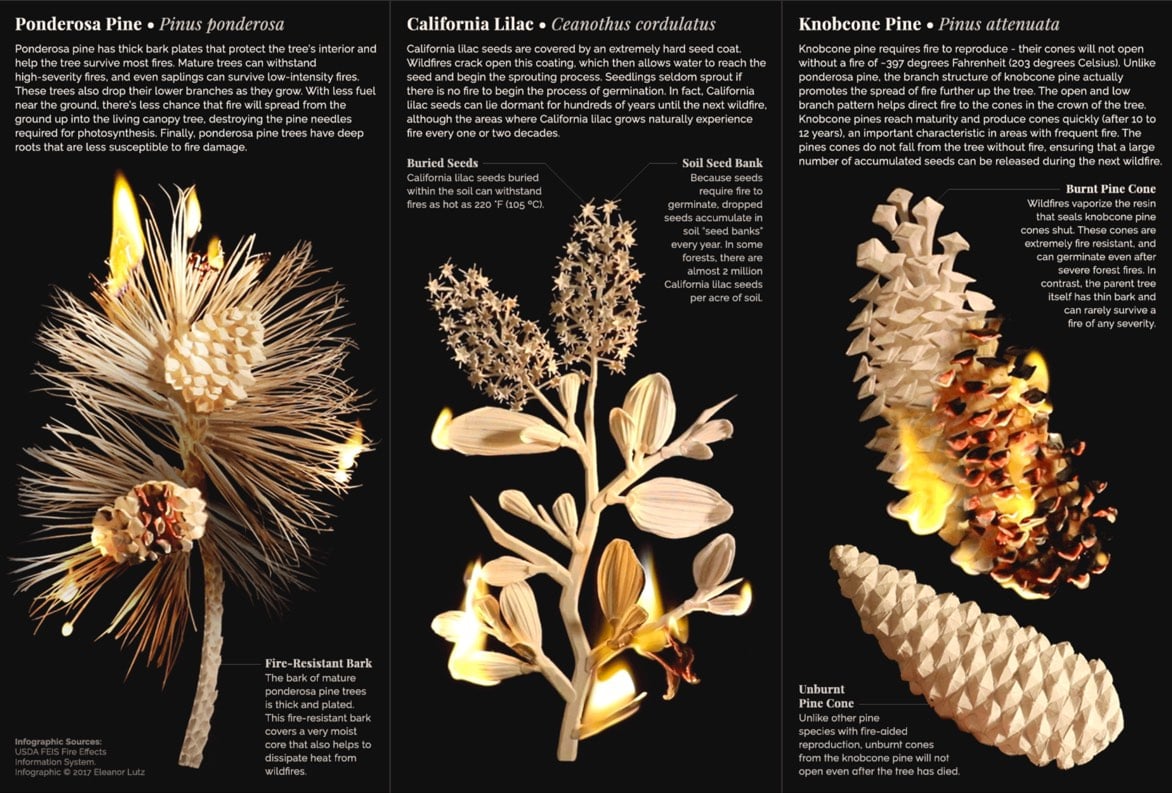

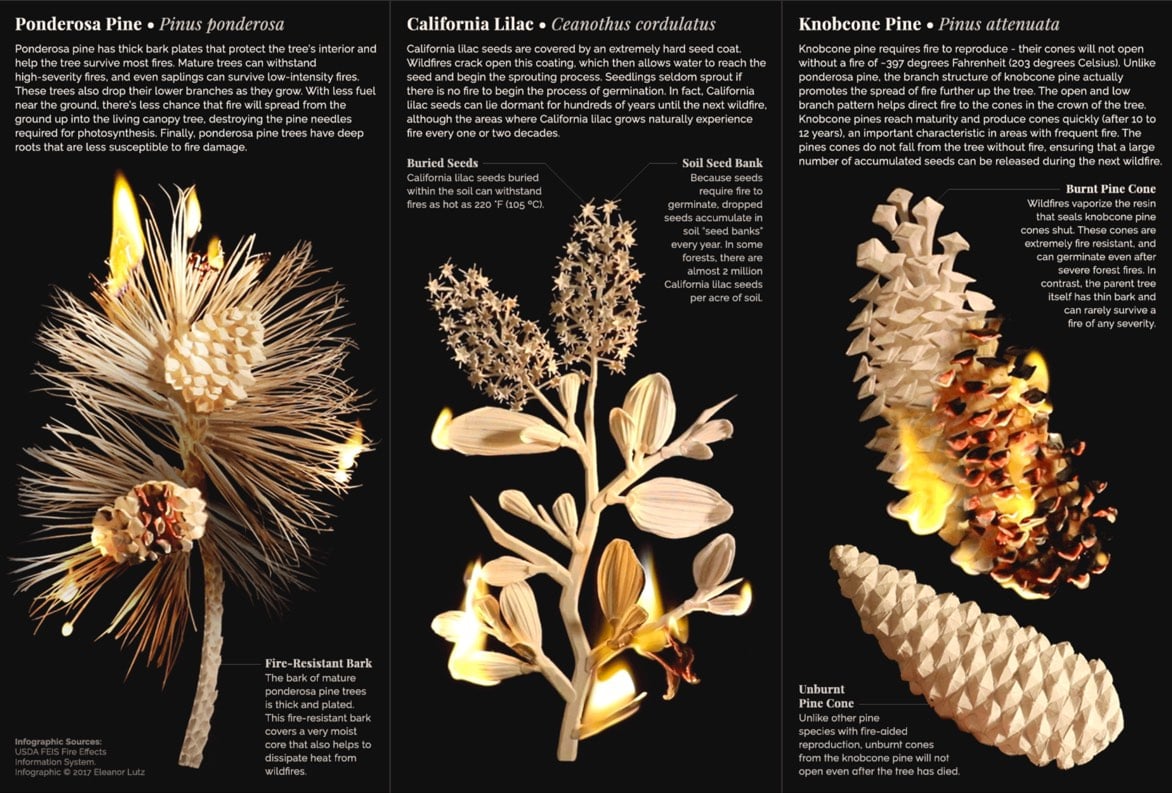

Eleanor Lutz made these nifty models of California plants that can withstand fire damage out of Elmer’s Glue and watercolor paper. She then photographed them burning for this infographic on how some species have adapted to California’s wildfires. Be sure to click through to see the animated version.

In this short video, Josh Begley shows all of the front pages of the NY Times in chronological order from 1852 to the present. The Times began publishing in 1851 so not every front page is represented, but that’s still more than 50,000 pages in less than a minute. Since they go by so quickly, here are some highlights:

Dec 11, 1861: The Times publishes their first illustrations on the front page. One is a map of Virginia and the other two are political cartoons lampooning James Gordon Bennett, founder of the New York Herald, one of the Times’ main rivals.

Apr 15, 1865: The front page columns were lined with black as they reported on the assassination of Lincoln.

Dec 1, 1896: The hyphen is dropped from “The New-York Times”.

Feb 10, 1897: The slogan “All the News That’s Fit to Print” appears for the first time on the front page.

May 30, 1910: The first news photograph appears on the front page, a photo of aviator Glenn Curtiss flying from Albany to NYC at the blistering pace of 54 mi/hr.

May 1, 1926: The Times prints the first photo “radioed” to the newspaper from London. Transmission time: 1hr 45m.

Jul 21, 1969: The first use of 96 pt. type on the front page announces the Apollo 11 landing on the Moon and subsequent moonwalk. The large type will also be used to announce Nixon’s resignation, the first day of 2000, 9/11, and the election of Barack Obama.

Sept 7, 1976: The columns on the front page are widened, reducing their number from 8 to 6.

Oct 16, 1997: The first color photo is printed on the front page of the Times. (The Times Machine scan is in B&W for some reason, but the photo was in color.)

Begley also made Best of Luck With the Wall, a video showing the entire extent of the US-Mexico border.

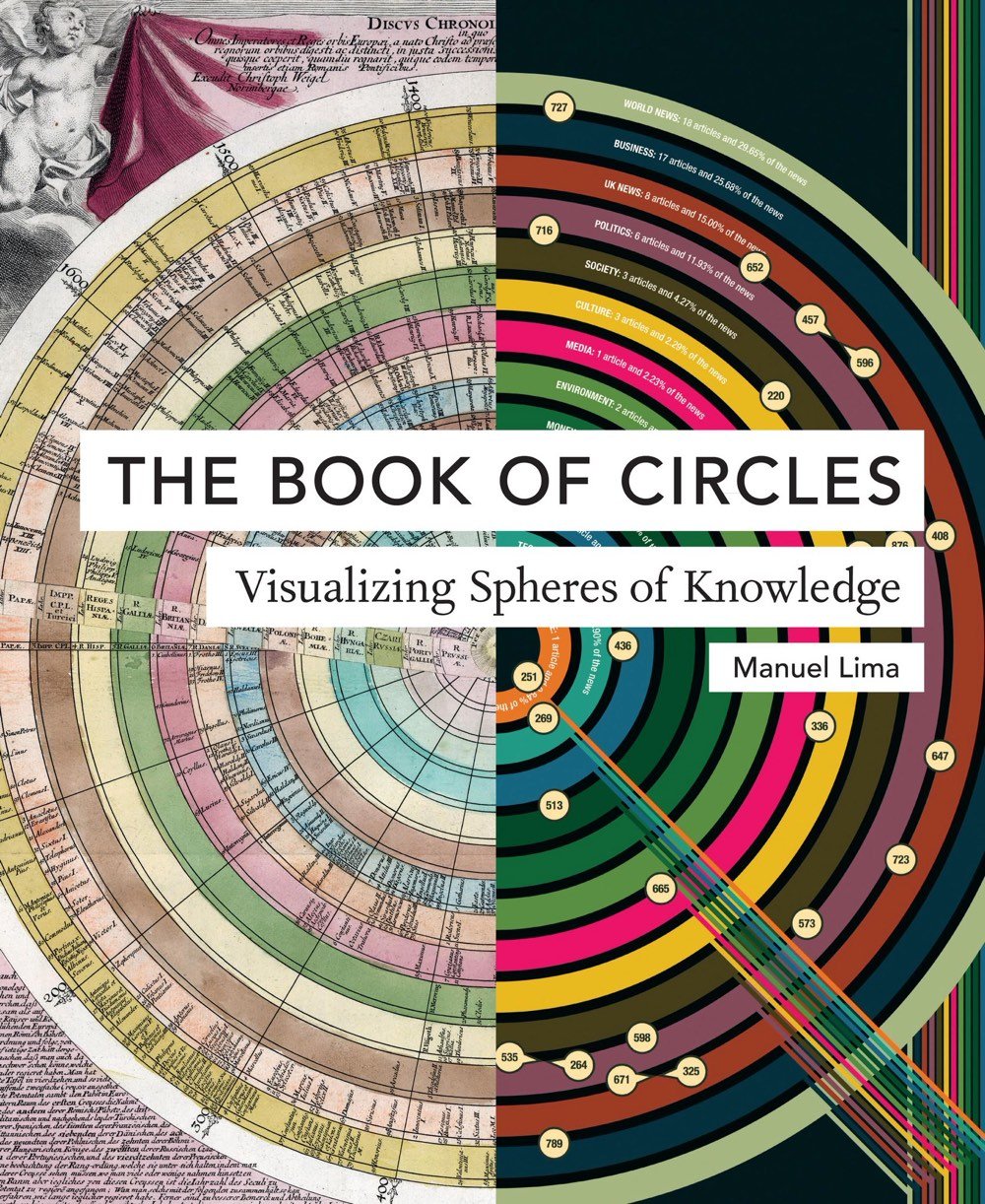

The Book of Circles is an upcoming book by Manuel Lima about the use of circles in information design.

In this follow-up to his hugely popular The Book of Trees and Visual Complexity, Manuel Lima takes us on a lively tour through millennia of circular information design. Three hundred detailed and colorful illustrations from around the world cover an encyclopedic array of subjects-architecture, urban planning, fine art, design, fashion, technology, religion, cartography, biology, astronomy, and physics, all based on the circle, the universal symbol of unity, wholeness, infinity, enlightenment, and perfection. Clay tokens used by ancient Sumerians as a system of recording trade are juxtaposed with logos of modern retailers like Target; Venn diagrams are discussed alongside the trefoil biohazard symbol, symbols of the Christian trinity, and the Olympic rings; and a diagram revealing the characteristics of ten thousand porn stars displays structural similarities to early celestial charts placing the earth at the center of the universe.

I have both of Lima’s previous books, The Book of Trees and Visual Complexity.

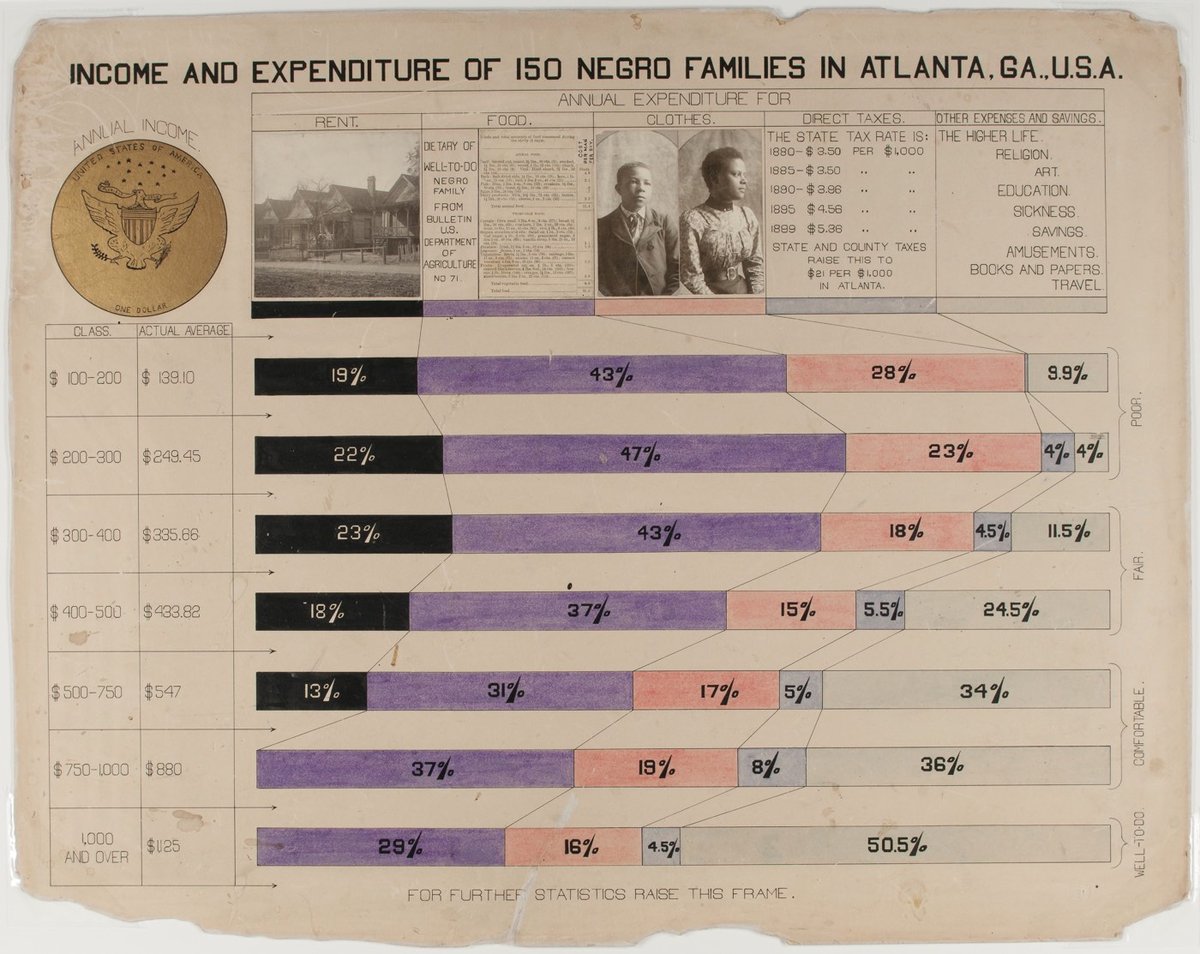

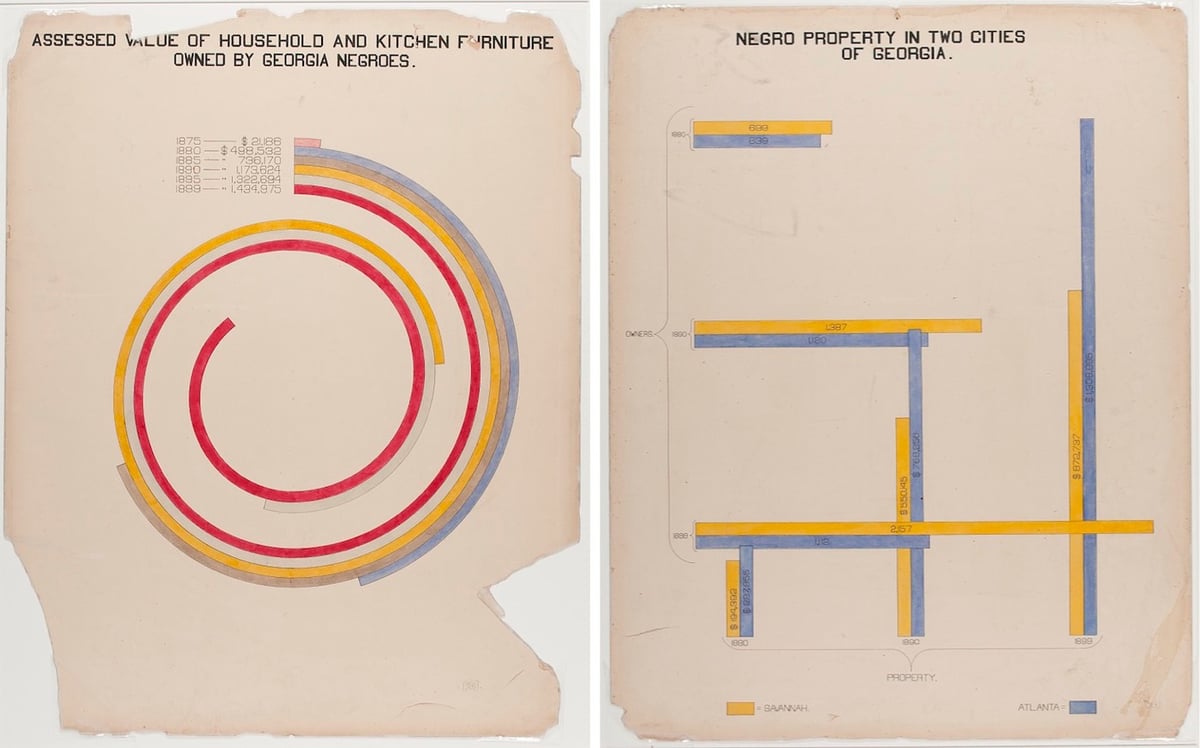

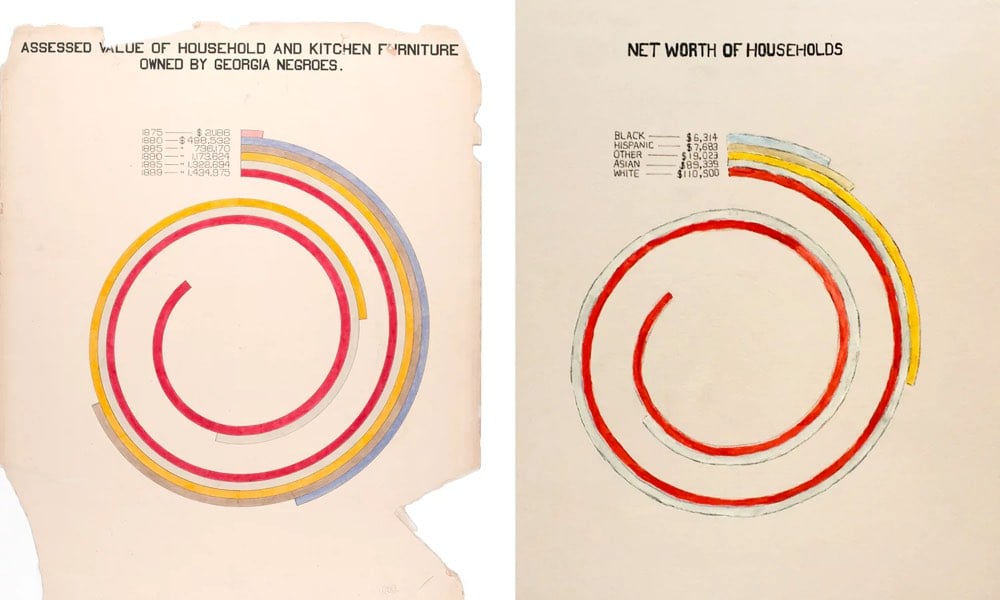

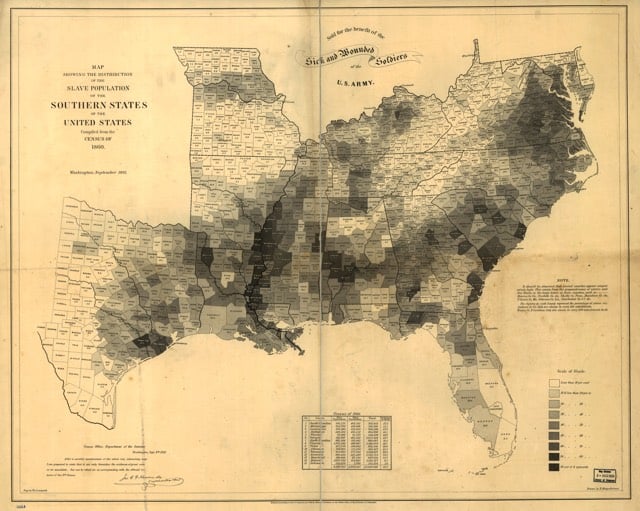

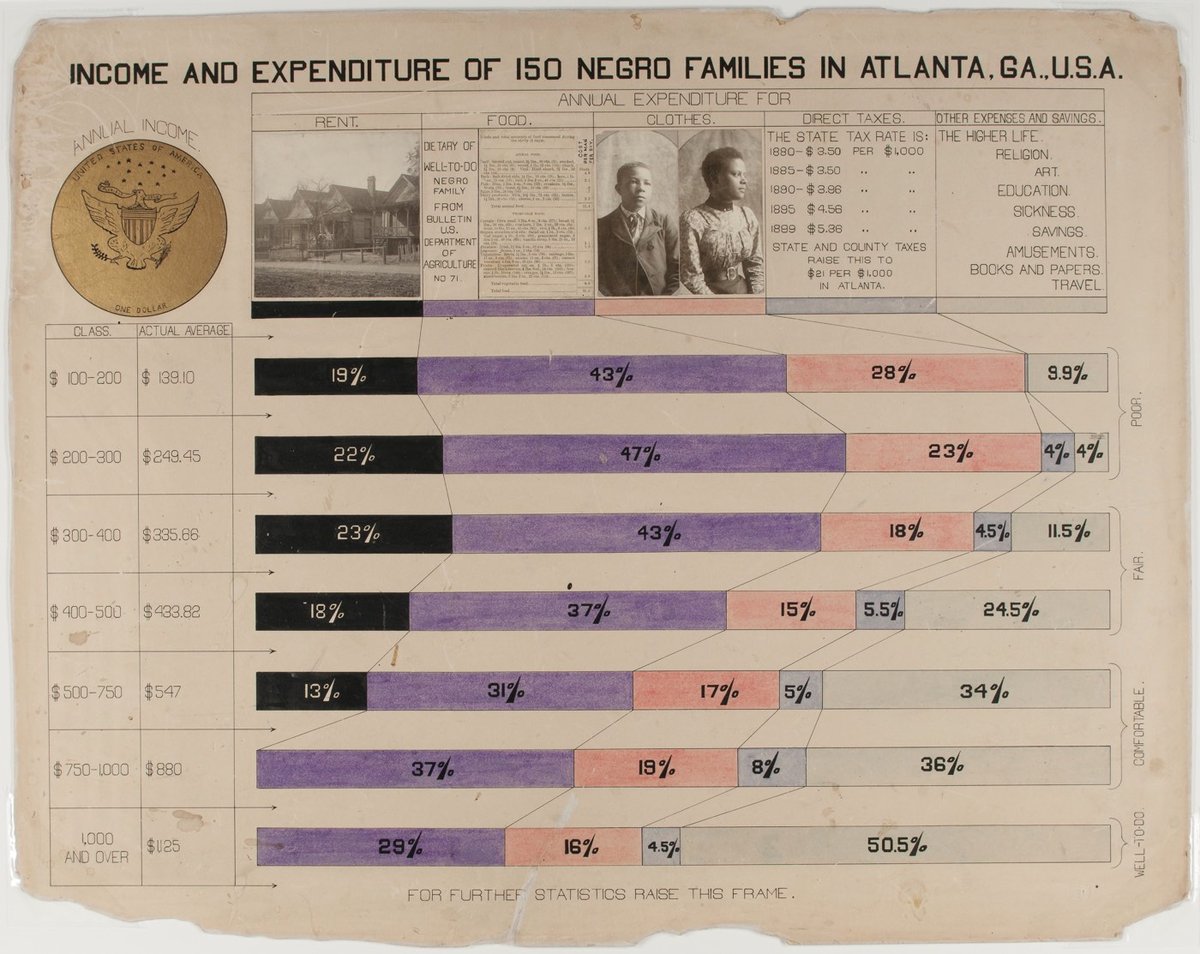

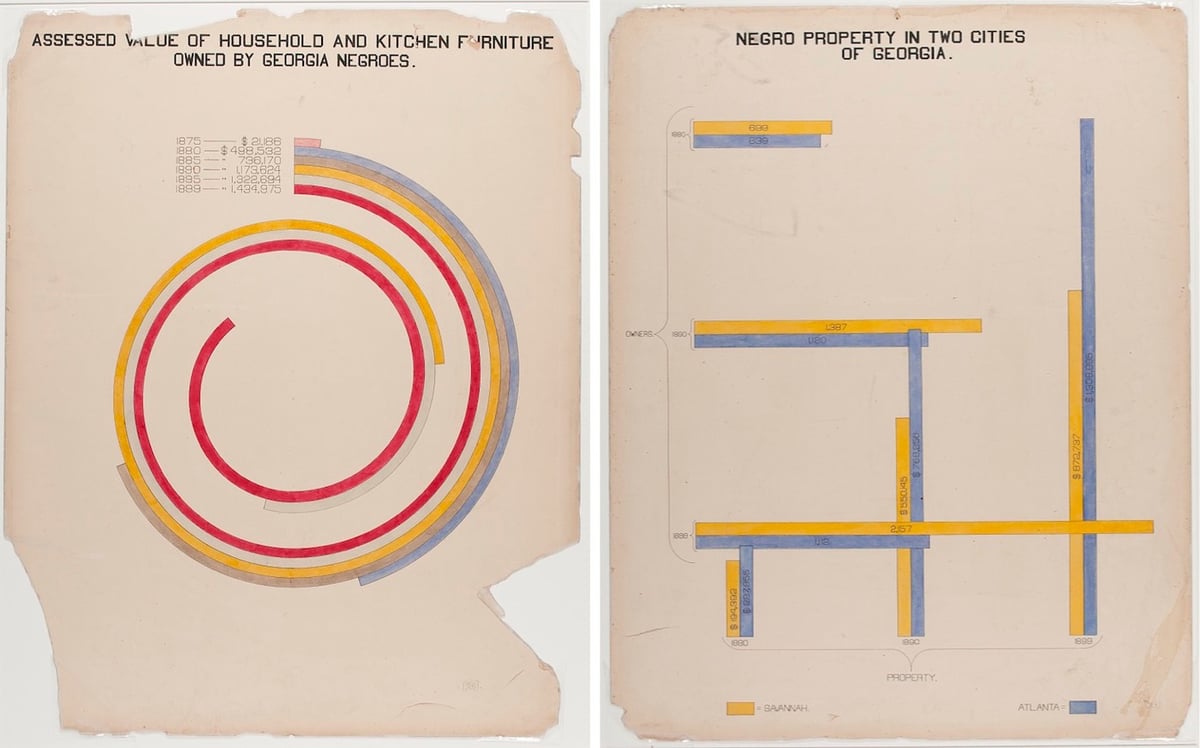

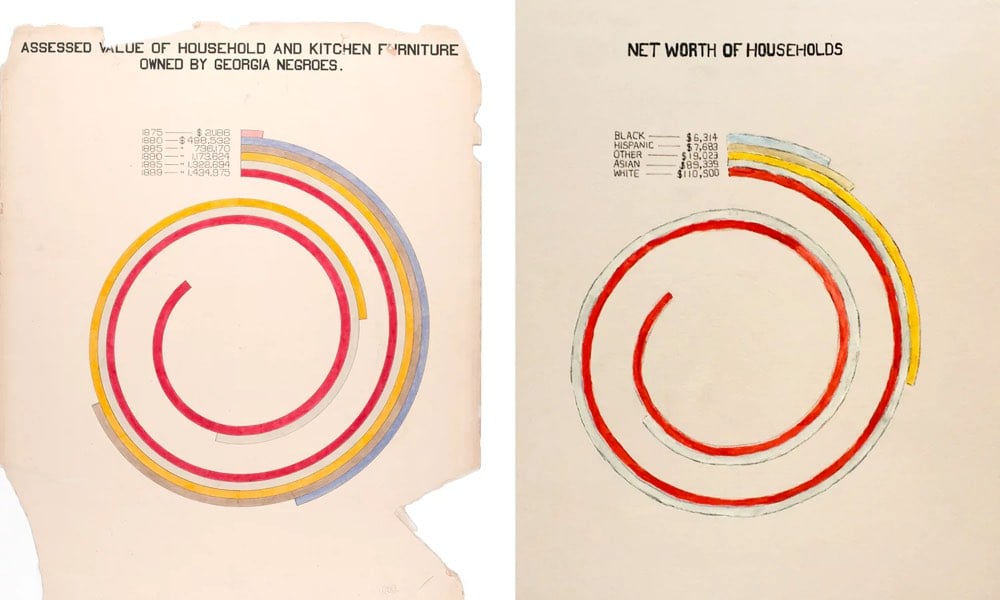

W.E.B. Du Bois was an American author, sociologist, historian, and activist. Apparently Du Bois was also a designer and design director of some talent as these hand-drawn infographics show.

In addition to an extensive collection of photographs, four volumes containing 400 official patents by African Americans, more than 200 books penned by African-American authors, various maps, and a statuette of Frederick Douglass, the exhibition featured a total of fifty-eight stunning hand-drawn charts (a selection of which we present below). Created by Du Bois and his students at Atlanta, the charts, many of which focus on economic life in Georgia, managed to condense an enormous amount of data into a set of aesthetically daring and easily digestible visualisations. As Alison Meier notes in Hyperallergic, “they’re strikingly vibrant and modern, almost anticipating the crossing lines of Piet Mondrian or the intersecting shapes of Wassily Kandinsky”.

Update: Oh, this is great: Mona Chalabi has updated Du Bois’ charts with current data.

Wealth. If I had stayed close to the original chart, the updated version would have shown that in 2015, African American households in Georgia had a median income of about $36,655, which would fail to capture the story of inflation (net asset numbers aren’t published as cumulative for one race). Instead, I wanted to see how wealth varies by race in America today.

The story is bleak. I hesitated to use the word “worth”, but it’s the language used by the Census Bureau when they’re collecting this data and, since money determines so much of an individual’s life, the word seems relevant. For every dollar a black household in America has in net assets, a white household has 16.5 more.

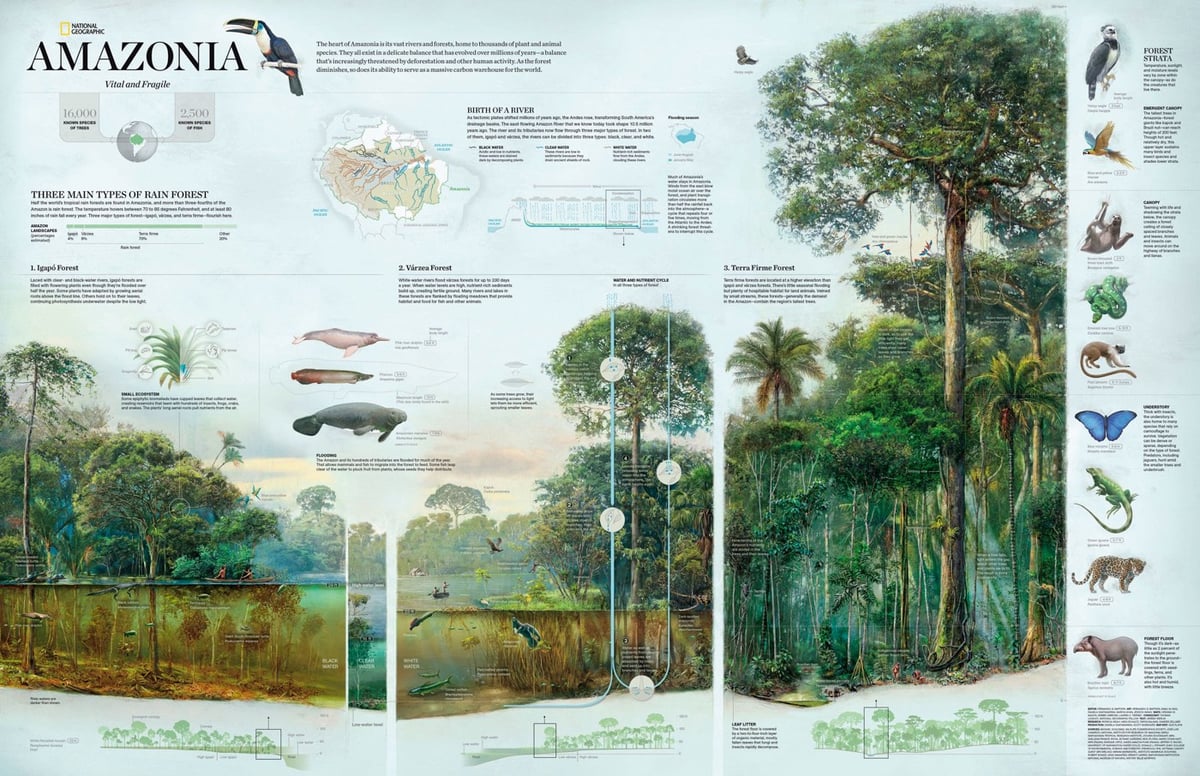

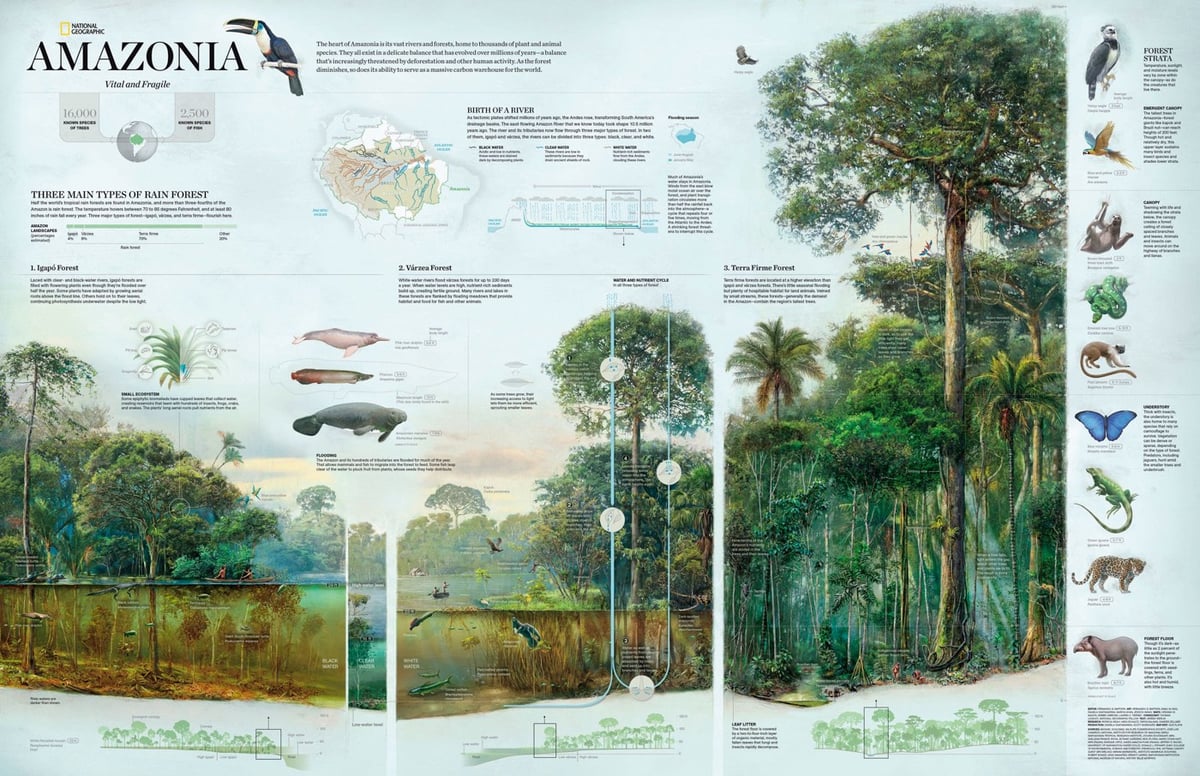

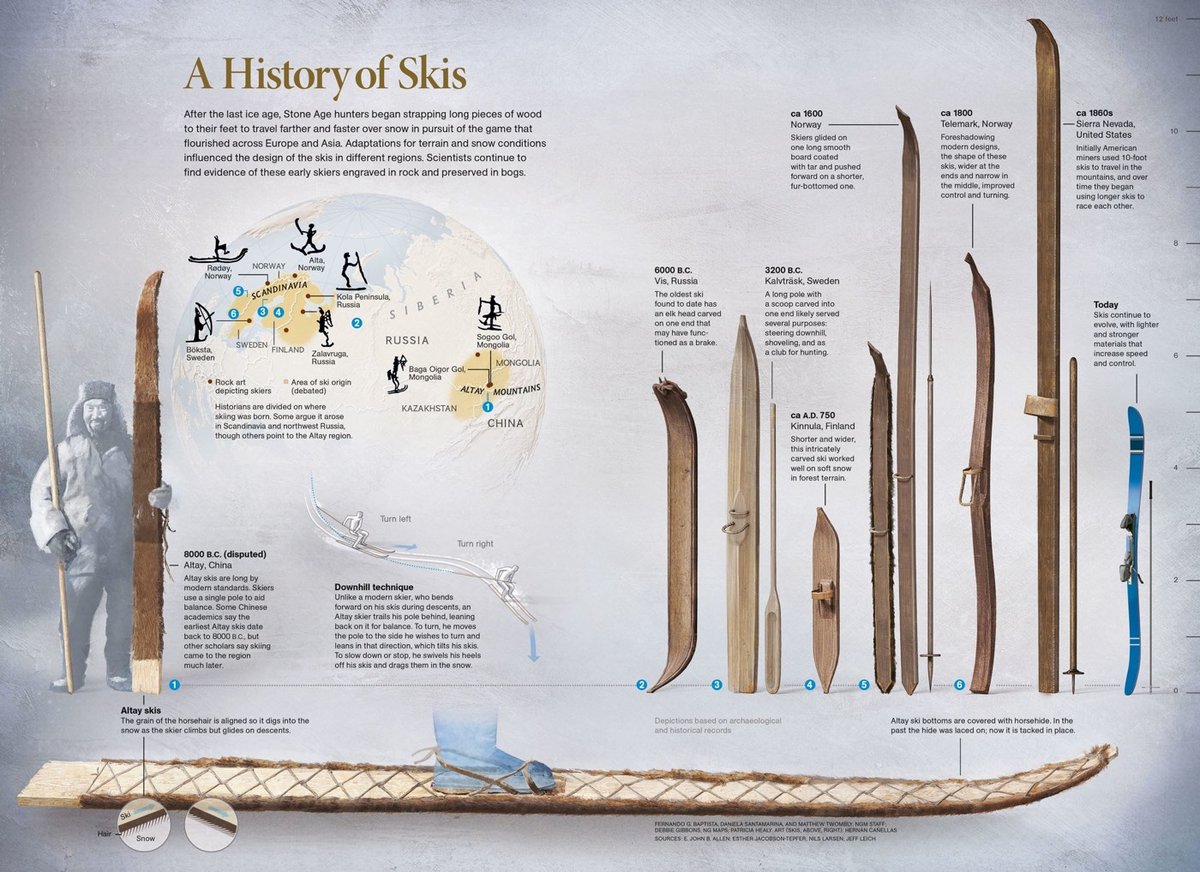

National Geographic Infographics is an anthology published by Taschen of some of the best infographics featured by National Geographic in the past 128 years.

Through seven sections — History, The Planet, Being Human, Animal World, World of Plants, Science and Technology, and Space — we encounter the rise and fall of the Roman Empire, the mysterious origins of the Easter Island statues, Cleopatra’s Alexandria and a history of Hawaiian surfboarding, all distilled in expert, accessible graphic form. We discover how our genetic patterns have been pieced together over the years or how hip-hop emerged as a cultural heavyweight; we get to grips with global warming, and explore our ever-expanding study of an ever-expanding universe.

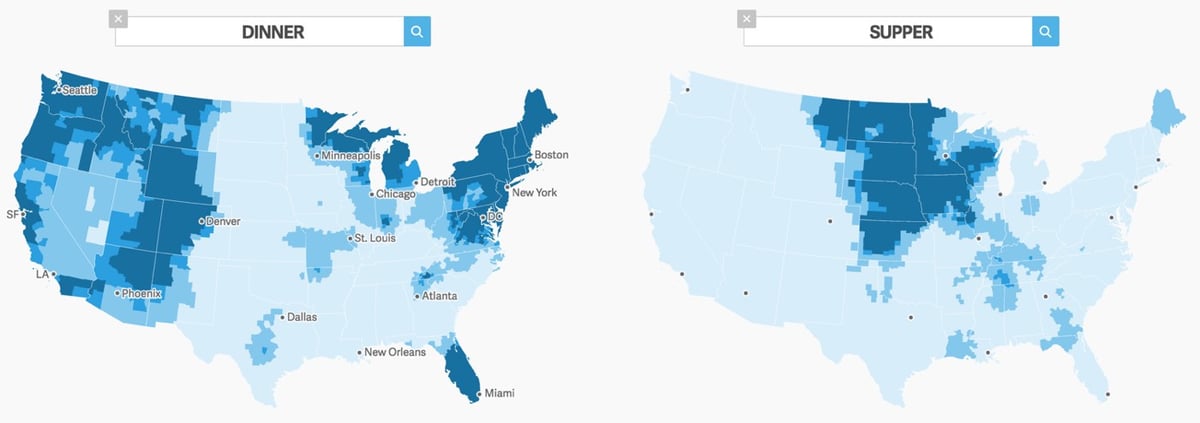

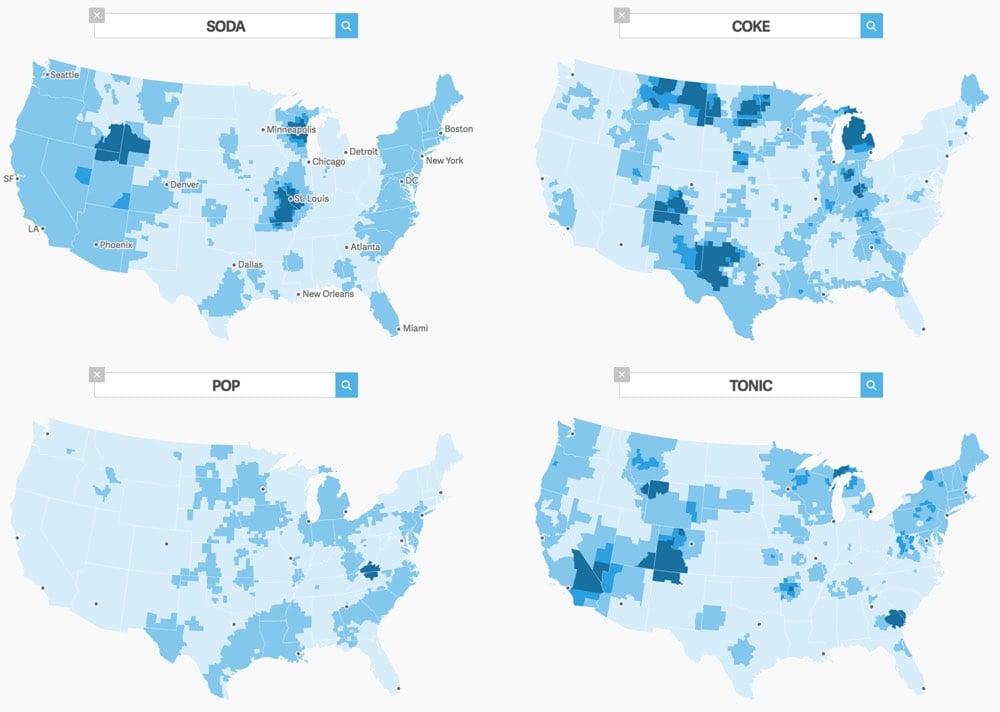

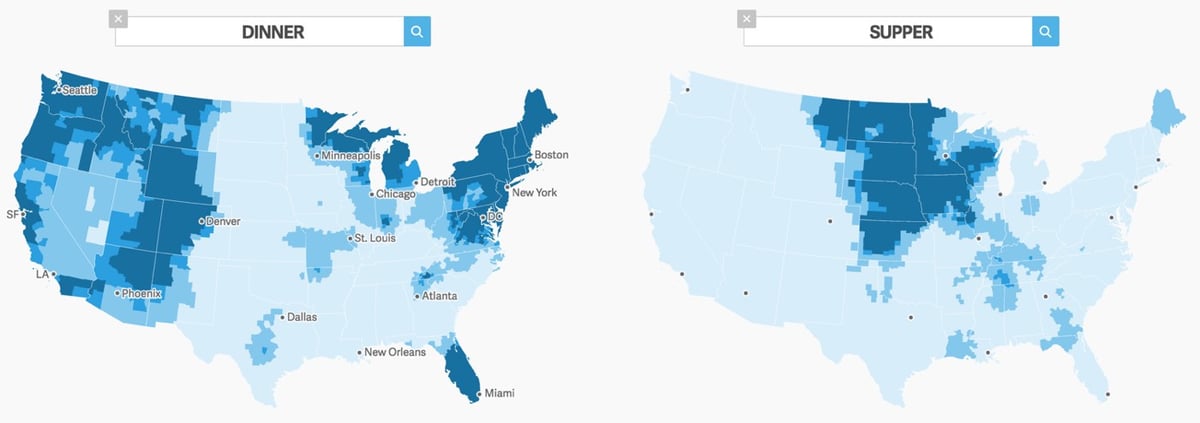

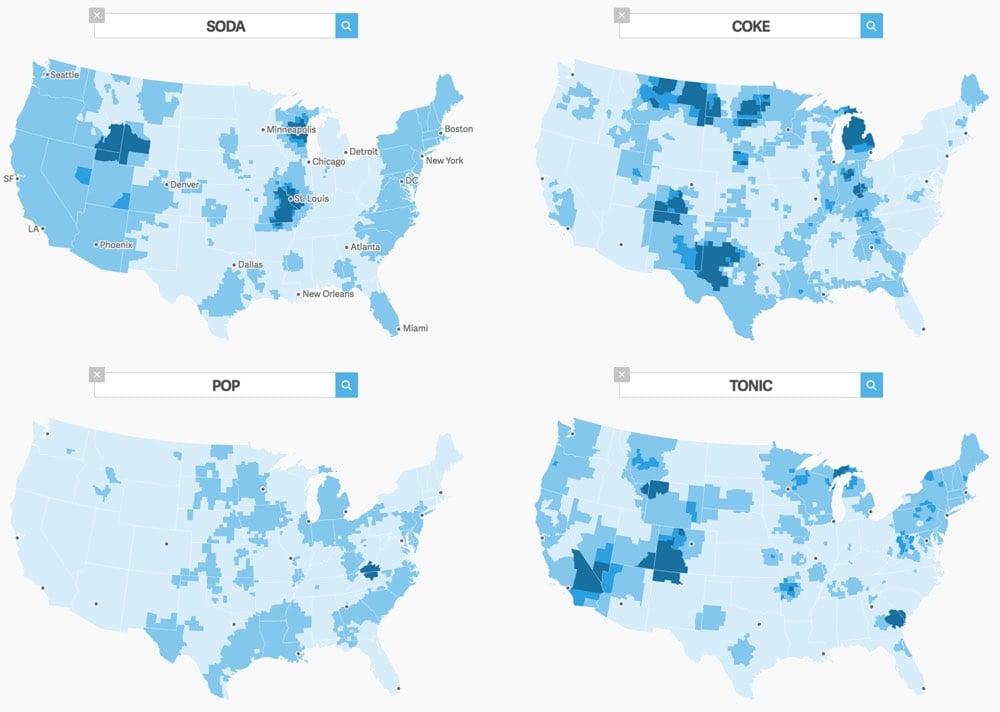

It’s that time of year again. No, not Christmas or Hanukkah. As the year winds down, it’s an opportunity for Americans to investigate how differently they use words in different parts of the country. In December 2013, for example, people lost their damn minds over the NY Times’ dialect quiz. This year, you can play around with The Great American Word Mapper which uses Twitter data from 2014 to plot geographic usage patterns.

For instance, you can see where people use “supper” vs. “dinner” (see above). The map indicates mixed usage where I grew up, which checks out…we mostly said “supper” but “dinner” was not uncommon, particularly as I got older. Other results are less useful…the Twitter-based “soda” vs. “coke” vs. “pop” doesn’t tell you as much as directly asking people what they call soft drinks.

The swearing maps are always fun (see also the United States of Swearing)…I wonder why “shit” is so relatively popular in the South?

Some other interesting searches: “moma” (alternate spelling of “momma” in the South with a small pocket of usage around NYC for MoMA), “city” doesn’t give the result you might expect, the distribution of “n***er” vs “n***a” suggests they are two different words with two different meanings, and in trying to find a search that would isolate just urban areas, the best I could come up with was “kanye” (or maybe “cocktails” or “traffic”). And harsh, map! Geez. (via @fromedome)

This is cool and a little mesmerizing: animated US maps showing the most popular baby name in each state from 1910 to 2014 for boys and girls. There are three separate visualizations. The first just shows the most popular baby name in each state. Watch as one dominant name takes over for another in just a couple of years…the Mary to Lisa to Jennifer transition in the 60s and 70s is like watching an epidemic spread. Celebrity names pop up and disappear, like Betty (after Betty Boop and Betty Grable?) and Shirley (after Shirley Temple) in the 30s. The boy’s names change a lot less until you start getting into the Brandons, Austins, and Tylers of the 90s.

The next visualization shows the most particularly popular name for each state, e.g. Brandy was the most Louisianan name for female newborns in 1975. And the third visualization shows each name plotted in the averaged geographical location of births — so you can see, for example, the northward migration of Amanda during the 80s.

P.S. Guess what the most popular boy’s name in the state of my birth was the year I was born? And the most particularly popular boy’s name in the state I moved to just a year later? Jason. I am basic af.

Update: From Flowing Data, some graphs of the most unisex names in US history. (thx, paul)

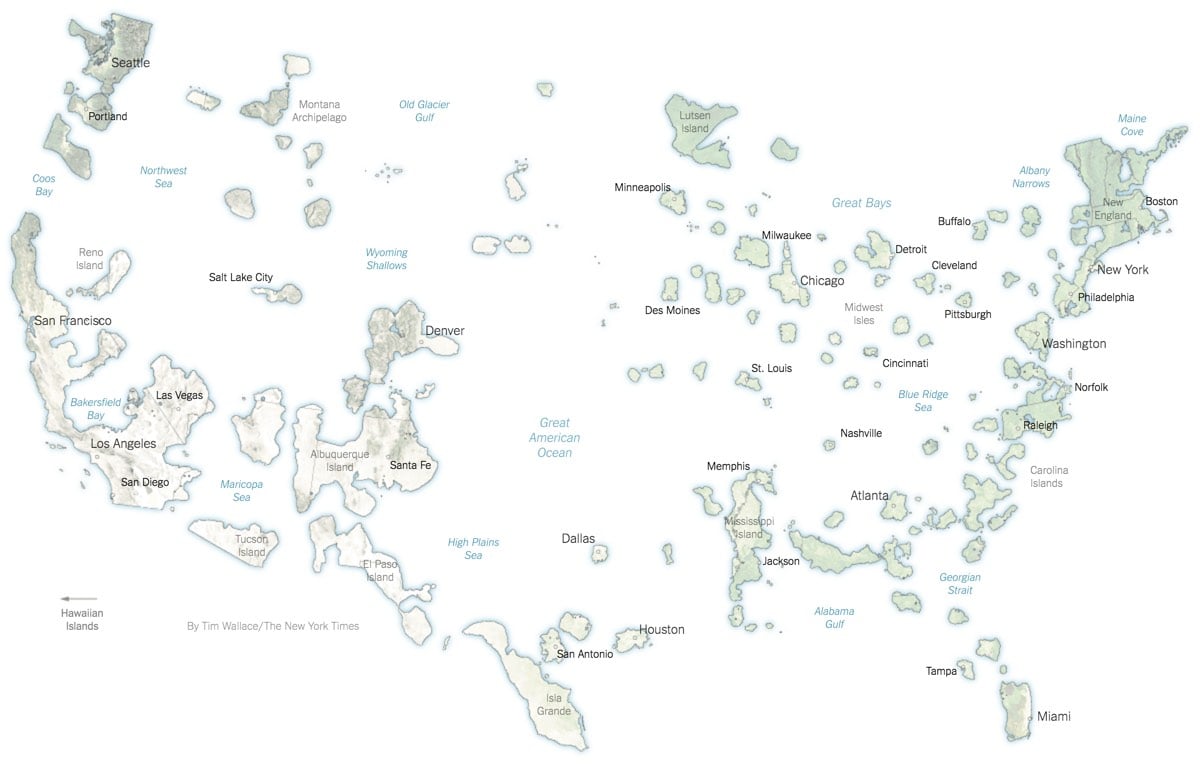

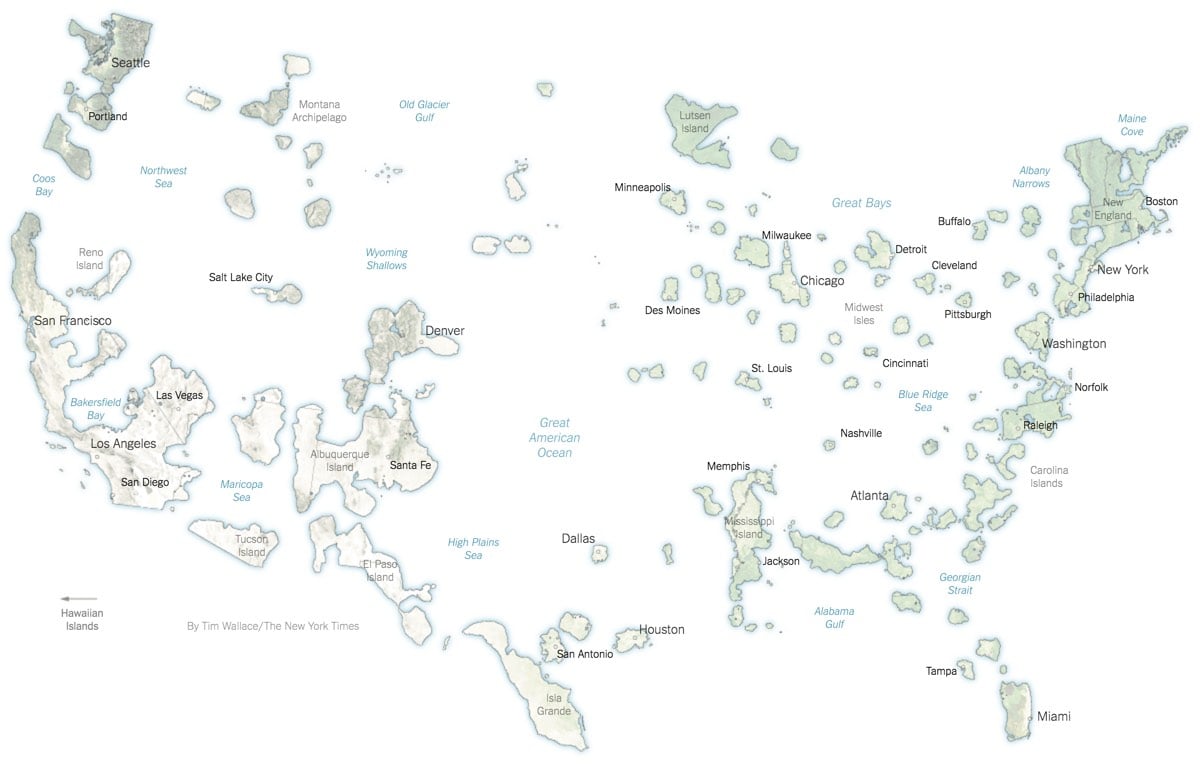

The New York Times took a map of the US and split it in two based on areas that voted for Clinton and Trump in the 2016 election. (Clinton’s map is pictured above.)

Mrs. Clinton’s island nation has large atolls and small island chains with liberal cores, like college towns, Native American reservations and areas with black and Hispanic majorities. While the land area is small, the residents here voted for Mrs. Clinton in large enough numbers to make her the winner of the overall popular vote.

That’s fun, but it’s another reminder of how strictly geographical maps distort election results.

P.S. They missed a real opportunity to call the chain of islands in the southern states The Cretaceous Atoll.

Neil Halloran, creator of the excellent Fallen of World War II interactive visualization of the casualties of WWII, is working on a similar visualization about the possible effects of a global nuclear conflict. He recently uploaded an in-progress video of the project with a special 2016 election message at the end. Amazing and scary to see how much of a difference WWII made in the global death rate and how minuscule that would be in comparison to a global nuclear war.

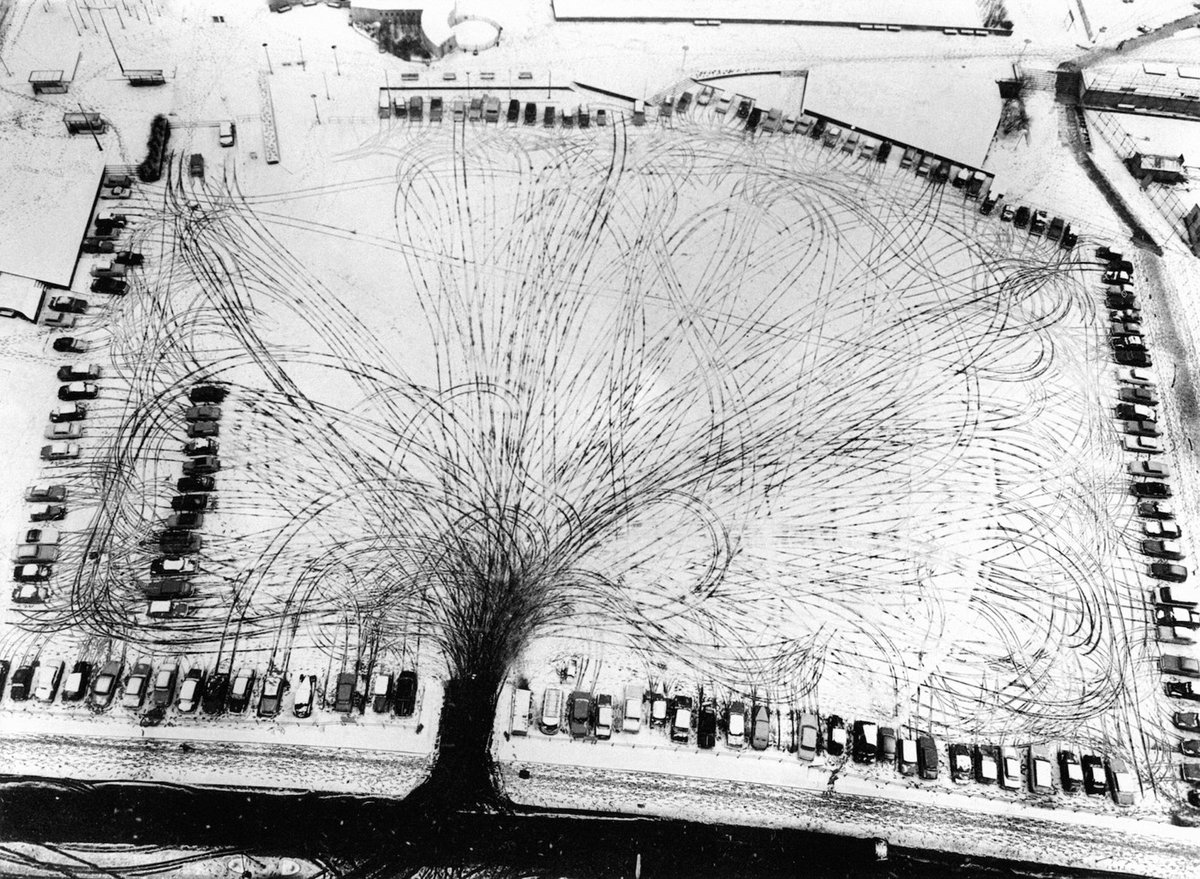

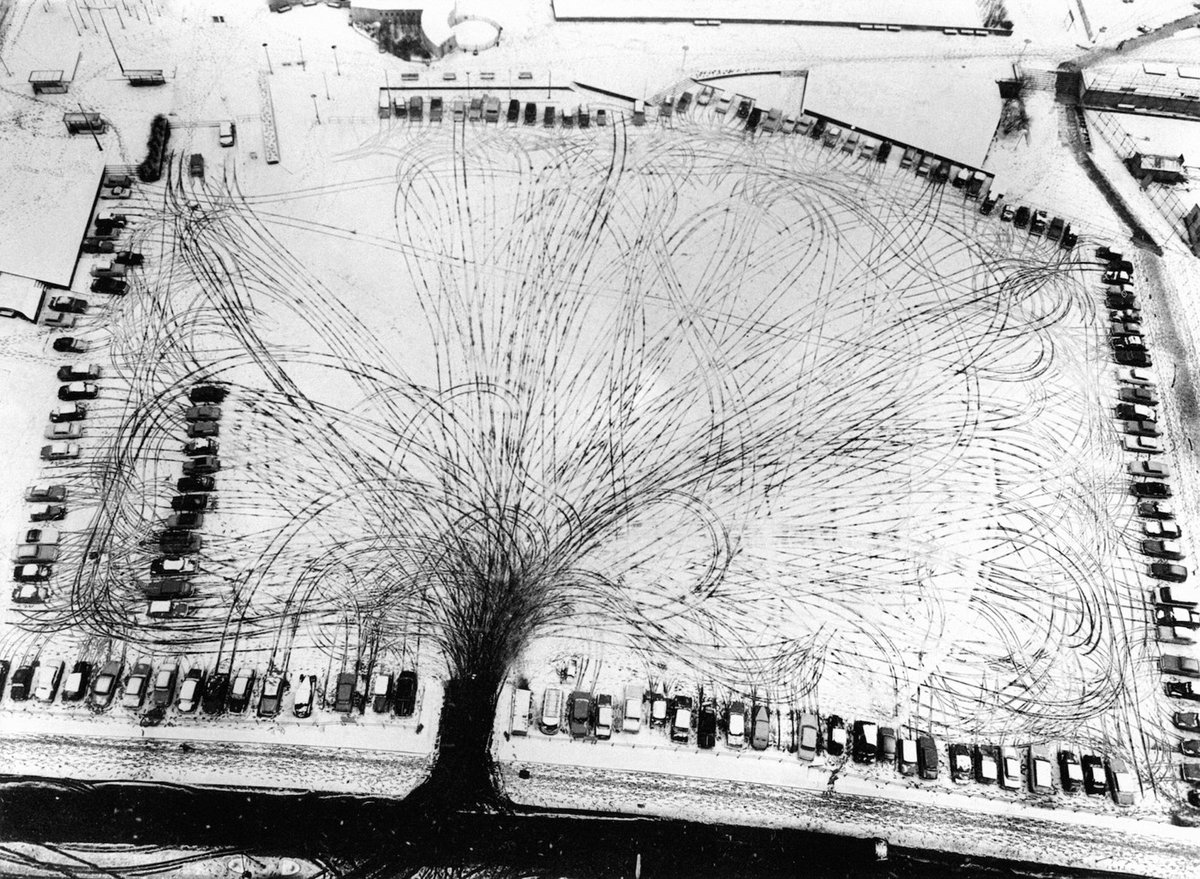

The tire tracks in this parking lot make a tree pattern in the snow, a self-producing infographic of the cars’ collective pathway to their parking spaces. It’s fun to trace individual tracks — I’m fascinated by the one that comes in, starts right, turns back to the left, then heads back down before turning toward the left again into a space.

The photo was taken in a Shell Centre parking lot near Waterloo Station in 1963. Photographer unknown. (via @robnitm)

Update: Nicholas Felton shared an annotated single-car version of a car’s tracks in the snow.

Update: A reader randomly picked up a copy of a book recently called The World From Above, “a pretty brilliant collection of aerial photographs, mostly black and white, published in the mid 60’s” and the parking lot photo was in it. No photographer listed, but the photo is credited to dpa, the German Press Agency. (thx, david)

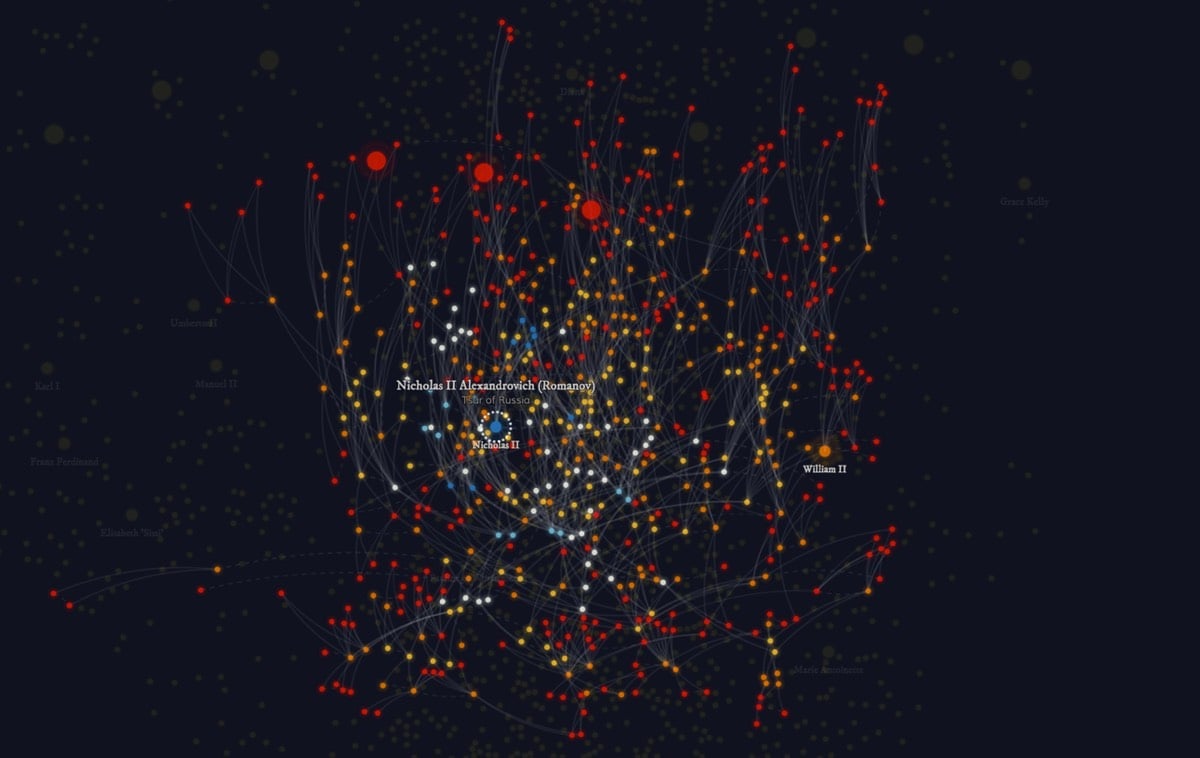

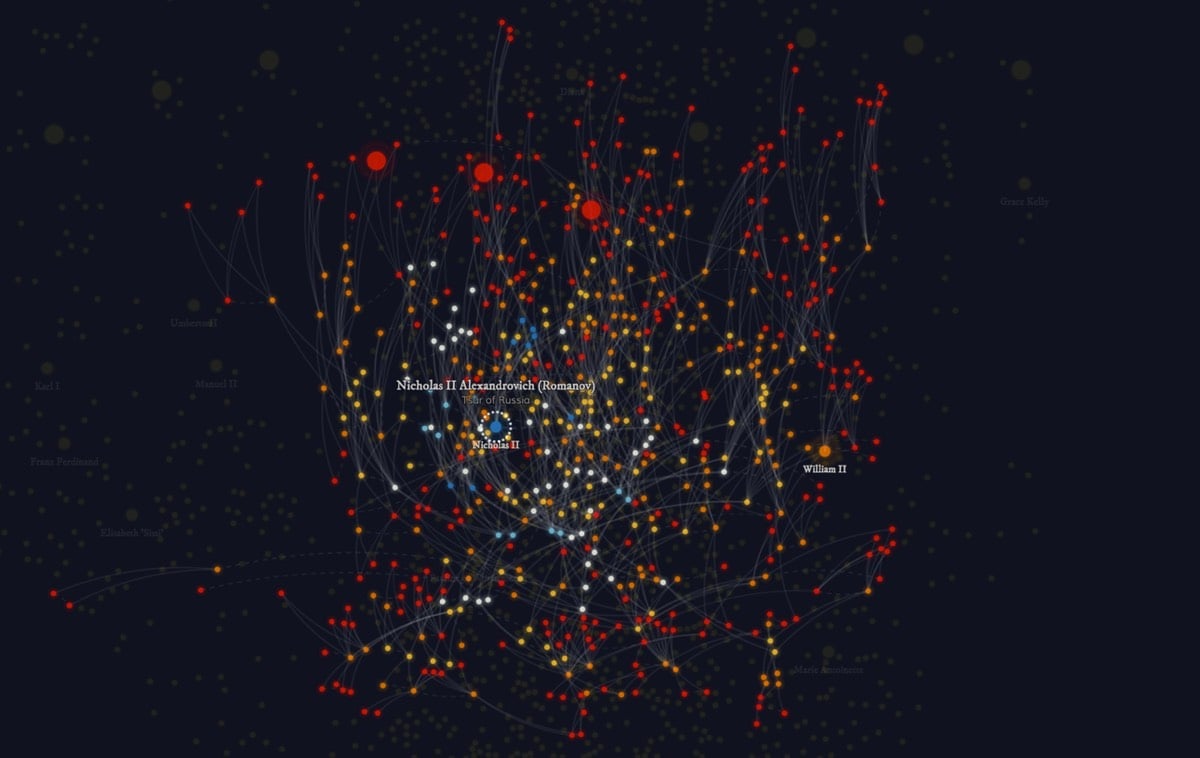

The United Kingdom, Spain, Denmark, Sweden, and six other European countries still have hereditary royal leaders and they are all related to each other. Royal Constellations is an interactive infographic for exploring the ancestral relationships of Europe’s royalty.

Royal & aristocratic families are known for their fondness of marrying within their own clique. Restraining aggression between two families, creating a stronger front towards a third family, increasing territorial acquisitions, legal claim to a foreign throne through inheritance are some of the most common reasons.

This leads to very interesting & entangled family trees which the visual below tries to convey. It shows how all 10 of the current hereditary royal leaders of Europe can be connected to each other through their ancestors. We don’t have to look very far back. Even the most distant royal relatives have their shared forebears born after the year 1700.

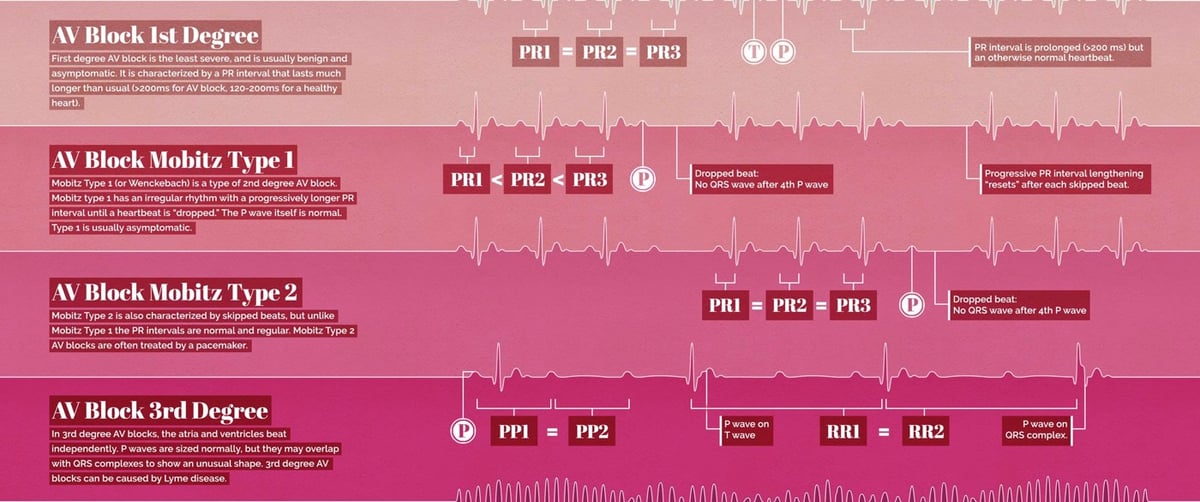

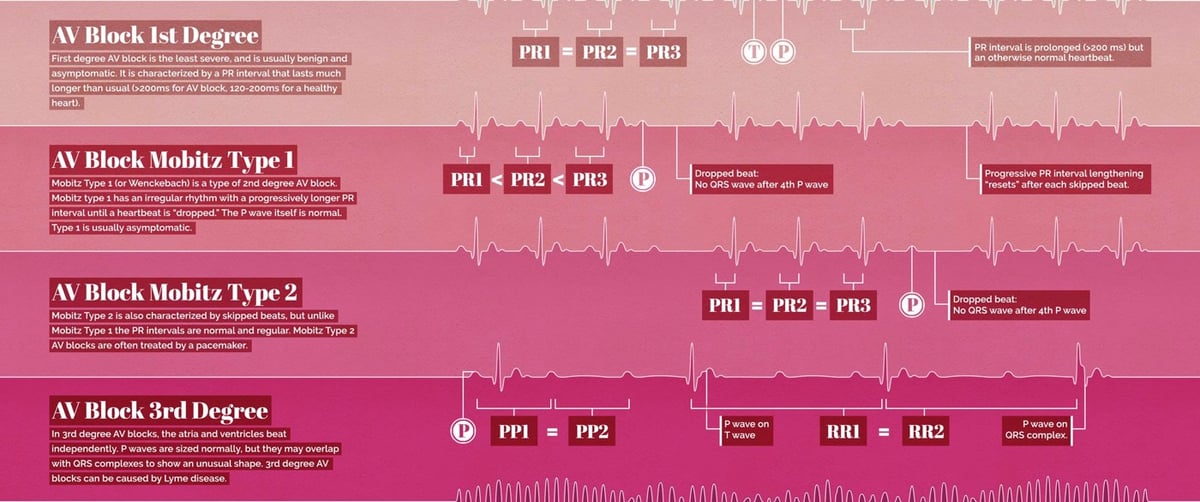

This is a lovely infographic from Eleanor Lutz of a bunch of different heartbeat EKG waves, from a normal heartbeat to a flatline to ventricular fibrillation (“must be treated immediately with CPR and defibrillation”.) Prints are available.

Mike Kelley has travelled to airports all over the world, photographing planes taking off and landing and then stitching them together into photos showing each airport’s traffic. (via @feltron whose book features an Airportrait on the cover)

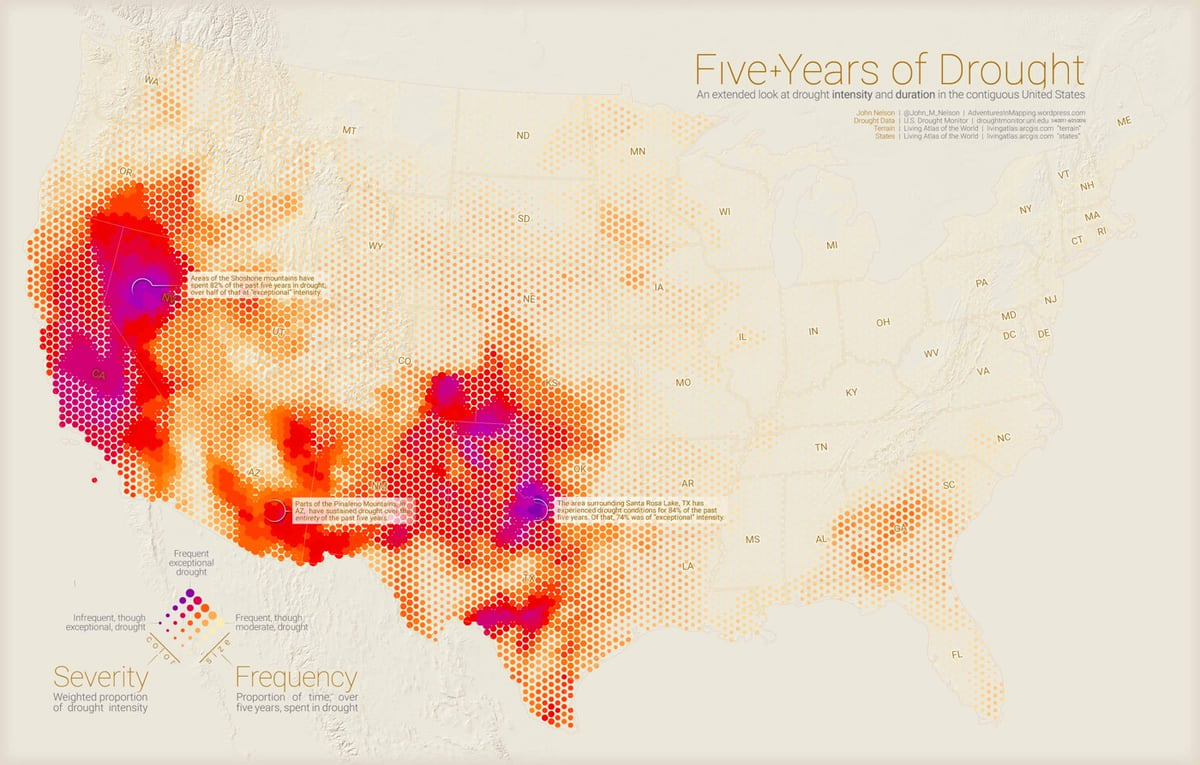

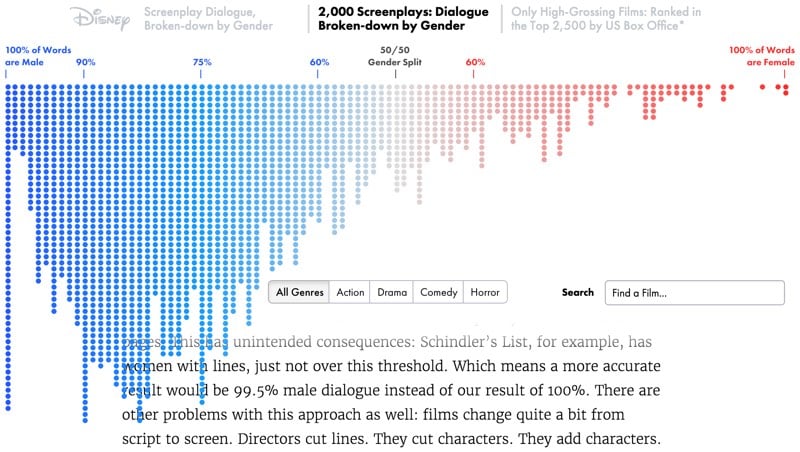

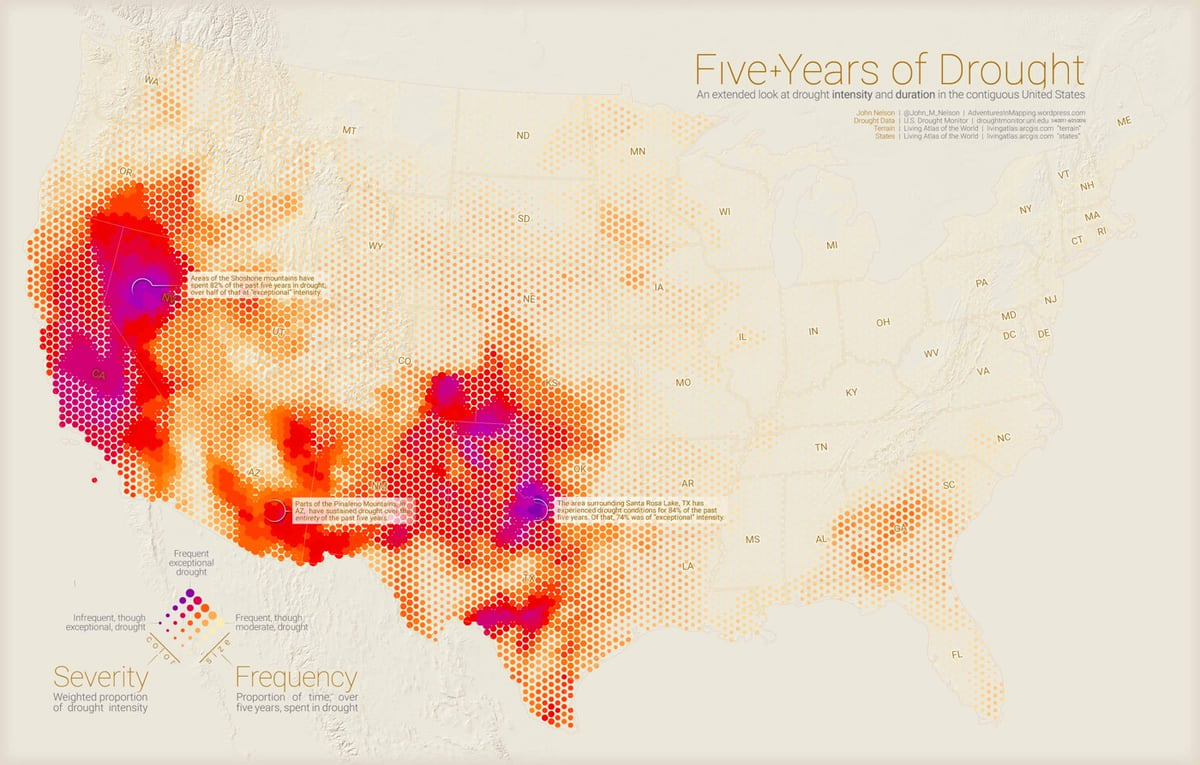

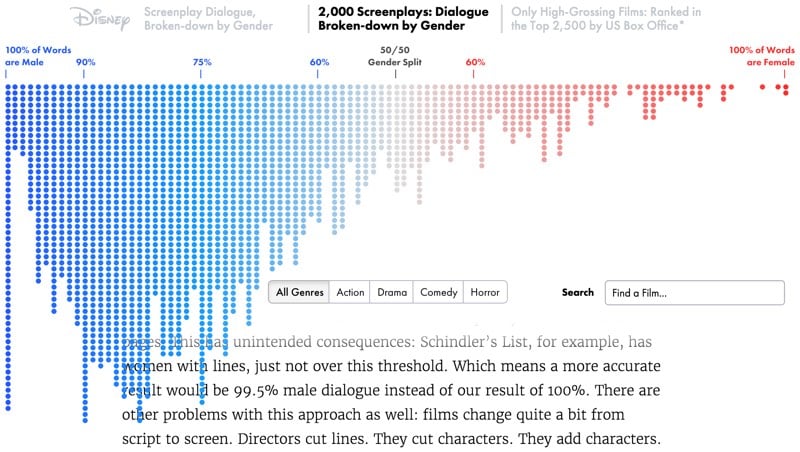

The Information is Beautiful Awards have announced the shortlist of nominees for the best infographics, data visualizations, and data journalism for 2016. Literally hours of exploration here. Some well-deserved shouts out to Polygraph (multiple projects, including their breakdown of film dialogue by gender and age), Nicholas Felton’s Photoviz, climate spirals, FiveThirtyEight’s 2016 election forecast map, and many other projects you might have seen here or elsewhere.

The images above are from Adventures in Mapping, Polygraph, and Shipmap.

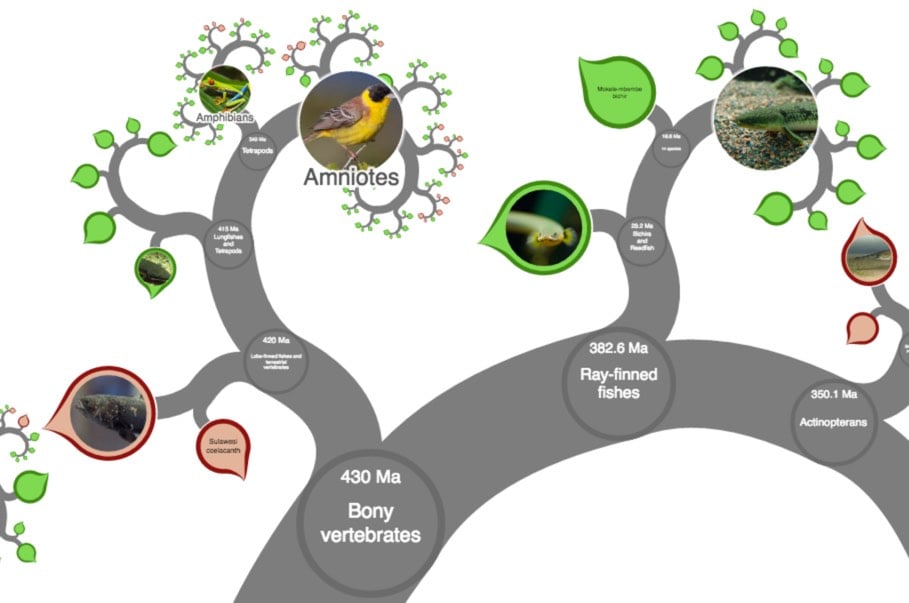

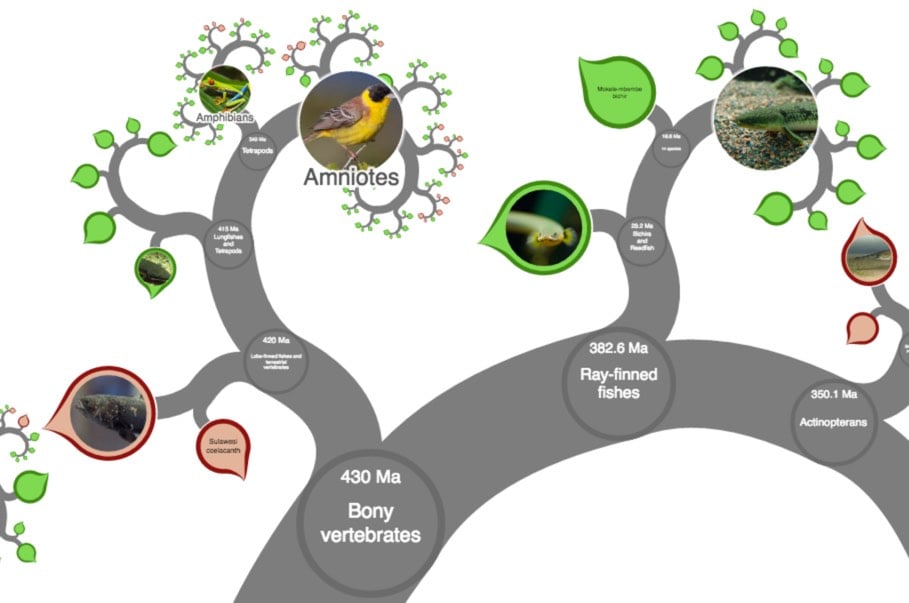

OneZoom is an interactive zoomable map of “the evolutionary relationships between the species on our planet”, aka tree of life. Browsing around is fun, but you’ll want to use the search function to find specific groups and animals, like mammals, humans, and mushrooms. The scale of this is amazing…there are dozens of levels of zoom. (via @pomeranian99)

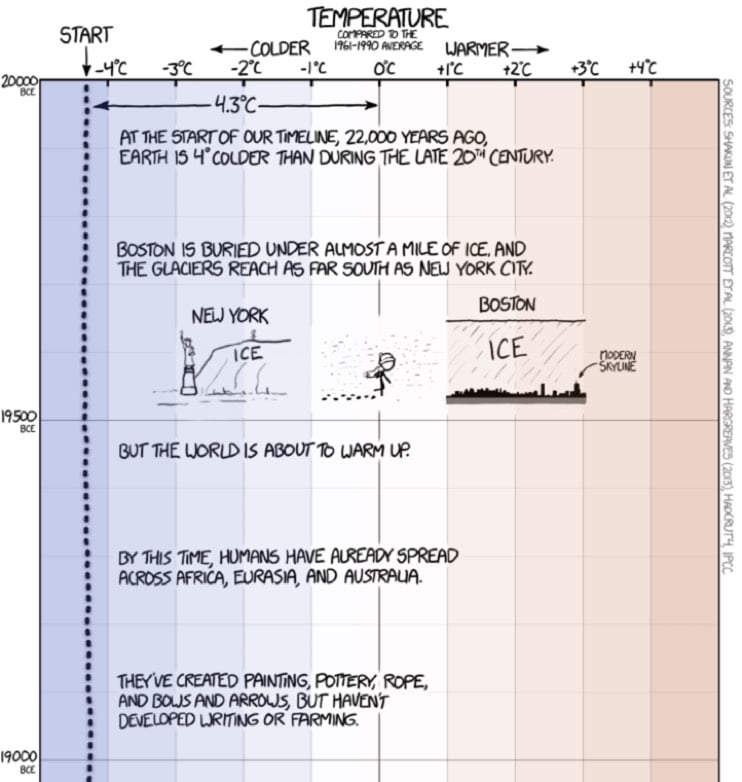

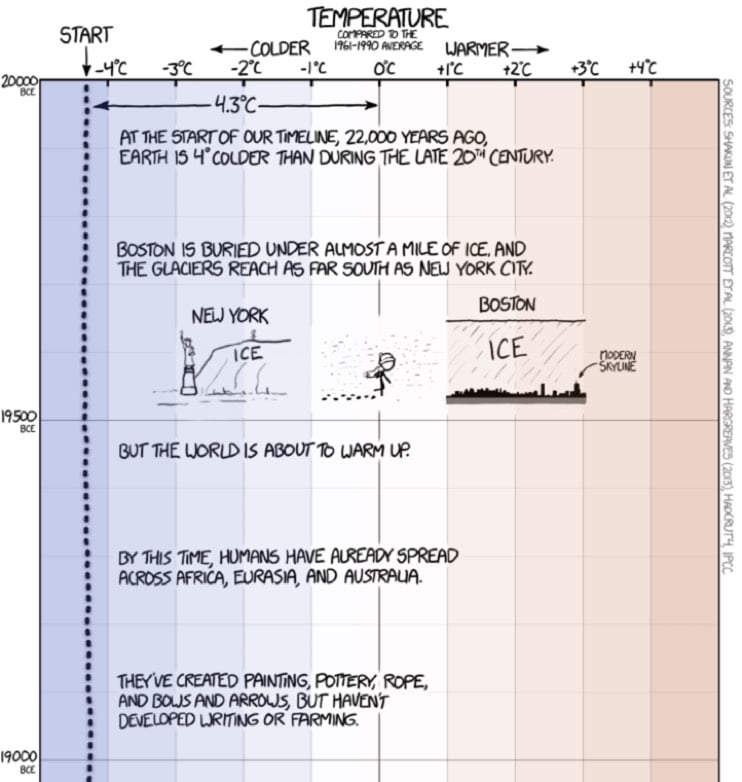

From XKCD, a typically fine illustration of climate change since the last ice age ~20,000 years ago.

When people say “the climate has changed before”, these are the kinds of changes they’re talking about.

And then in the alt text on the image:

[After setting your car on fire] Listen, your car’s temperature has changed before.

The chart is a perfect use of scale to illustrate a point about what the data actually shows. Tufte would be proud.

Update: Tufte is proud. (via @pixelcult)

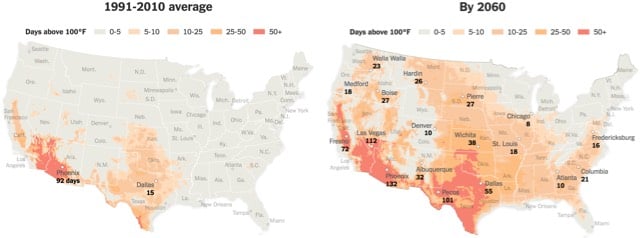

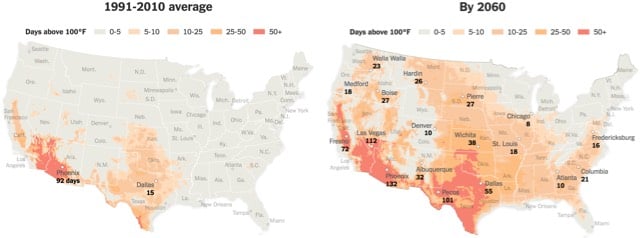

In today’s installment of terrifying graphics about climate change, the NY Times made a series of three maps showing the potential rise of 100 degree temperatures across the United States if current greenhouse gas emission trends continue through the end of this century. Look at the areas in orange and red on the 1991-2010 map: what sort of landscape do you picture? Keeping that landscape picture in your mind, look at the orange and red areas on the 2060 and 2100 maps. Yep! And Phoenix with 163 days above 100 degrees — that’s every day from March 25th to September 4th over 100 degrees.

P.S. A word about climate change and rising temperatures. The temperature that climate scientists typically reference and care about with regard to climate change is “the average global temperature across land and ocean surface areas”. According to the NOAA, the average temperature of the Earth in the 20th century was 13.9°C (57.0°F). In 2015, the average global temperature was 0.90°C (1.62°F) above that.

In order to avoid dangerous effects of climate change, climate scientists advocate keeping the global average temperature increase below 2 degrees (and more recently, below 1.5 degrees). In late 2015, 195 nations came together in Paris and agreed to:

[Hold] the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels and to pursue efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels, recognizing that this would significantly reduce the risks and impacts of climate change

That’s degrees Celsius, not Fahrenheit. I don’t know about you, but as an American, when I hear 2 degrees, I think, oh, that’s not bad. But 2°C is an increase of 3.6°F, which does seem significant.

Note also that it specifies keeping the temperature “below pre-industrial levels” and not below 20th century levels. It is maddeningly difficult to track down an exact figure for the pre-industrial global temperature, partially because of a lack of precise data, partially because of politics, and partially because of the impenetrability of scientific writing. From a piece Eric Holthaus wrote for FiveThirtyEight earlier this year:

It sounds easy enough to measure global warming: see how hot it was, compare it to how hot it used to be. But climate scientists have several ways of measuring how hot it used to be. NASA’s base period, as I mentioned above, is an average of 1951-80 global temperatures, mostly because that was the most recently available 30-year period when the data set was first created. By chance, it’s also pretty representative of the world’s 20th-century climate and can help us understand how much warmer the world has become while many of us have been alive.

Other organizations go further back. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, the body of climate scientists that was formed to provide assessments to the United Nations, bases its temperature calculations on an 1850-1900 global average. There was about 0.4 degrees of warming between that time period and the NASA base period.

Climate scientists often refer to that 1850-1900 timespan as “pre-industrial” because we don’t have comprehensive temperature data from the 1700s. But meteorologist Michael Mann, director of Penn State University’s Earth System Science Center, has argued that an additional 0.25 degrees of warming occurred between the start of the Industrial Revolution (around 1750) and 1850. Including Mann’s adjustment would bring February 2016 global temperatures at or very near 2 degrees above the “pre-industrial” average.

I now completely understand why some people deny that anthropogenic climate change is happening. Seriously. I looked for more than 30 minutes for a report or scientific paper that stated the average global temperature for 1850-1900 and I couldn’t find one. I looked at UN reports, NASA reports, reports from the UK: nothing. There were tons of references to temperatures relative to the 1850-1900 baseline, but no absolute temperatures were given. Now, I don’t mean to get all Feynman here, but this is bullshit. When the world got together in Paris and talked about a 1.5 degree increase, was everyone even talking about the same thing? You might begin to wonder what the scientists are hiding with their obfuscation.

Anyway, the important point is that according to climate scientists, we are already flirting with 1.5°C of global warming since pre-industrial times. Which means that without action, the spread of those Phoenician temperatures across the circa-2100 United States is a thing that’s going to happen.

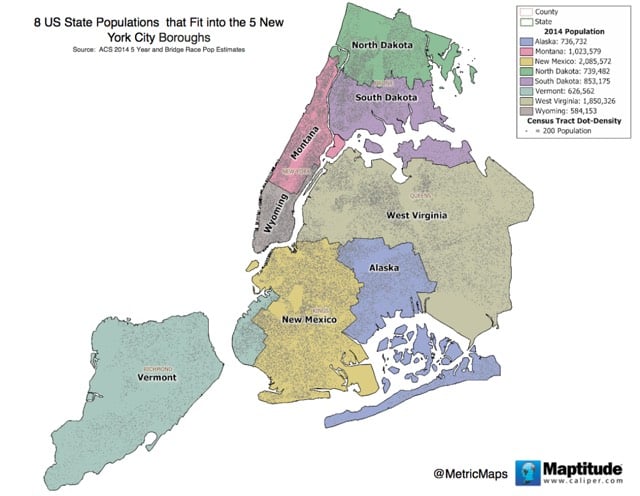

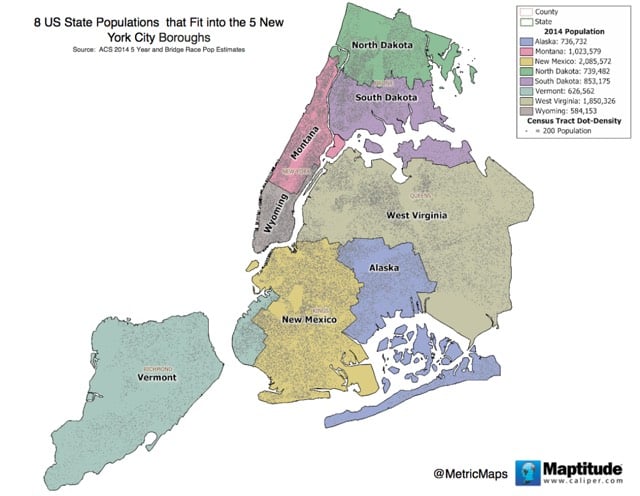

The population of NYC is equal to the combined populations of Vermont, Alaska, New Mexico, North Dakota, South Dakota, Wyoming, Montana, and West Virginia. Here’s what that looks like on a map.

Put another way: 16 US Senators represent as many people in those states as a fraction of one of New York States’ Senators represent the population of NYC. A Senator from Wyoming represents 290,000 people while one from New York represents 9.8 million people…and in California, there are 19 million people per Senator. That gives a Wyoming resident 65 times the voting power of a California resident.

Oh, this new book from Jennifer Daniel and New Scientist looks great: The Origin of (almost) Everything.

Together they take us on a whistle-stop tour from the start of our universe (through the history of stars, galaxies, meteorites, the Moon and dark energy) to our planet (through oceans and weather to oil) and life (through dinosaurs to emotions and sex) to civilization (from cities to alcohol and cooking), knowledge (from alphabets to alchemy) ending up with technology (computers to rocket science). Witty essays explore the concepts alongside enlightening infographics that zoom from how many people have ever lived to showing you how a left-wing brain differs from a right-wing one.

And Stephen Hawking wrote the foreword. You fancy, Jennifer Daniel!

From Clive Thompson, a history of the infographic, which was developed in part to help solve problems with an abundance of data available in the 19th century.

The idea of visualizing data is old: After all, that’s what a map is — a representation of geographic information — and we’ve had maps for about 8,000 years. But it was rare to graph anything other than geography. Only a few examples exist: Around the 11th century, a now-anonymous scribe created a chart of how the planets moved through the sky. By the 18th century, scientists were warming to the idea of arranging knowledge visually. The British polymath Joseph Priestley produced a “Chart of Biography,” plotting the lives of about 2,000 historical figures on a timeline. A picture, he argued, conveyed the information “with more exactness, and in much less time, than it [would take] by reading.”

Still, data visualization was rare because data was rare. That began to change rapidly in the early 19th century, because countries began to collect-and publish-reams of information about their weather, economic activity and population. “For the first time, you could deal with important social issues with hard facts, if you could find a way to analyze it,” says Michael Friendly, a professor of psychology at York University who studies the history of data visualization. “The age of data really began.”

Using the results of a recent report by a team of Yale researchers, this visualization shows the growth of urbanization across the globe from 3700 BC to the present day. There is an amazing flurry of activity in the last few seconds of the video because:

By 2030, 75 percent of the world’s population is expected to be living in cities. Today, about 54 percent of us do. In 1960, only 34 percent of the world lived in cities.

There are now 21 Chinese cities alone with a population of over 4 million.

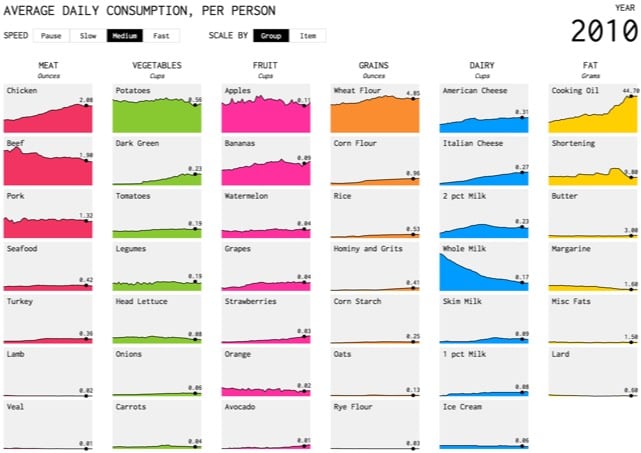

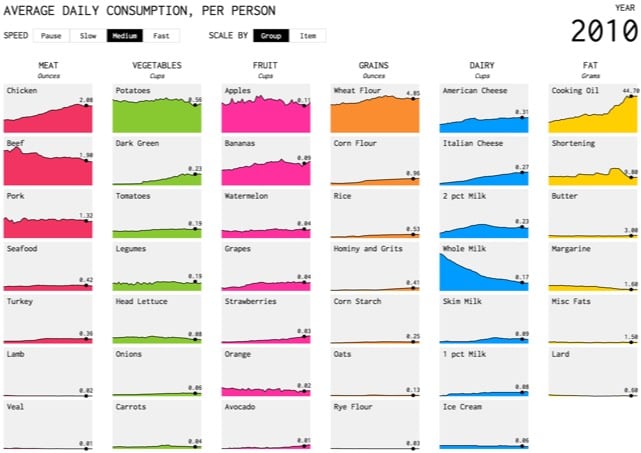

From Flowing Data, an animated infographic that shows how the American diet has changed since 1970. We eat less beef, potatoes, margarine, and whole milk than we used to, but more chicken, cooking oil, bananas, and Italian cheese.

Newer posts

Older posts

Socials & More