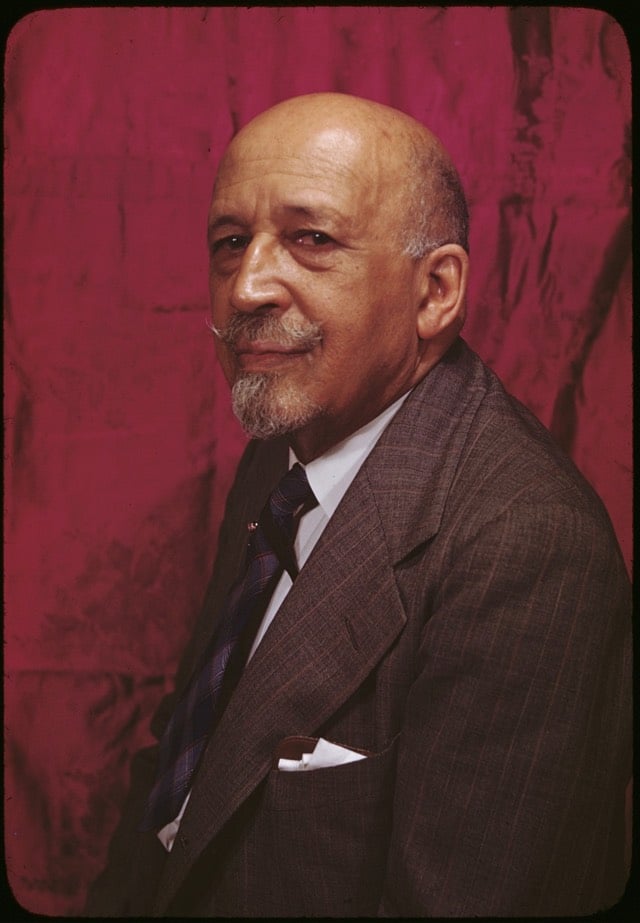

Tomorrow, February 23, is William Edward Burghardt Du Bois’s birthday. Du Bois was born in 1868 and died in 1963. In fact, Du Bois died, in Ghana, the day before the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. Roy Wilkins and hundreds of thousands of marchers observed Du Bois’s death with a moment of silence.

Du Bois is one of the most influential and important thinkers in American history. He wrote many, many speeches, essays, and books that are essential to understanding American culture, society, labor, and politics, particularly as they affected and were affected in turn by black people.

My favorite Du Bois essay, and one of the first I ever read, was and probably still is “Criteria of Negro Art.” It was written and published in 1926, and first presented as a speech in honor of Carter Woodson. I have in the last few years met otherwise extremely well-read people who knew nothing of this essay and have since sworn an oath to remedy that wherever possible. So you get to read some excerpts from it now.

The Big Idea of the essay is really formulated in the fourth paragraph:

What do we want? What is the thing we are after? As it was phrased last night it had a certain truth: We want to be Americans, full-fledged Americans, with all the rights of other American citizens. But is that all? Do we want simply to be Americans? Once in a while through all of us there flashes some clairvoyance, some clear idea, of what America really is. We who are dark can see America in a way that white Americans cannot. And seeing our country thus, are we satisfied with its present goals and ideals?

The answer to this first question “What do we want?” is Art, the proper appreciation of Beauty and Freedom; and the answer to the last question, “are we satisfied with [America’s] present goals and ideals?” is, of course, No.

In the twelfth paragraph, Du Bois argues that the lives of black Americans, not just the emerging intellectual bourgeoisie of the 1920s, but the lives of all black Americans, for their entire history, are the proper subject of this new kind of Art:

This is brought to us peculiarly when as artists we face our own past as a people. There has come to us — and it has come especially through the man we are going to honor tonight — a realization of that past, of which for long years we have been ashamed, for which we have apologized. We thought nothing could come out of that past which we wanted to remember; which we wanted to hand down to our children. Suddenly, this same past is taking on form, color, and reality, and in a half shamefaced way we are beginning to be proud of it. We are remembering that the romance of the world did not die and lie forgotten in the Middle Age [sic]; that if you want romance to deal with you must have it here and now and in your own hands.

Du Bois, after all, was a sociologist, and knew how to mobilize facts and figures; he does so in this anecdote, about black soldiers who fought in the Great War:

Have you heard the story of the conquest of German East Africa? Listen to the untold tale: There were 40,000 black men and 4,000 white men who talked German. There were 20,000 black men and 12,000 white men who talked English. There were 10,000 black men and 400 white men who talked French. In Africa then where the Mountains of the Moon raised their white and snow-capped heads into the mouth of the tropic sun, where Nile and Congo rise and the Great Lakes swim, these men fought; they struggled on mountain, hill and valley, in river, lake and swamp, until in masses they sickened, crawled and died; until the 4,000 white Germans had become mostly bleached bones; until nearly all the 12,000 white Englishmen had returned to South Africa, and the 400 Frenchmen to Belgium and Heaven; all except a mere handful of the white men died; but thousands of black men from East, West and South Africa, from Nigeria and the Valley of the Nile, and from the West Indies still struggled, fought and died. For four years they fought and won and lost German East Africa; and all you hear about it is that England and Belgium conquered German Africa for the allies!

In the 18th paragraph, he demolishes the premise that the success of black artists in and of itself is evidence of racial progress as such:

With the growing recognition of Negro artists in spite of the severe handicaps, one comforting thing is occurring to both white and black. They are whispering, “Here is a way out. Here is the real solution of the color problem. The recognition accorded Cullen, Hughes, Fauset, White and others shows there is no real color line. Keep quiet! Don’t complain! Work! All will be well!”

And beginning in the 21st paragraph, he quickly, and with startling beauty, poses the real problem for black artists working in America:

There is in New York tonight a black woman molding clay by herself in a little bare room, because there is not a single school of sculpture in New York where she is welcome. Surely there are doors she might burst through, but when God makes a sculptor He does not always make the pushing sort of person who beats his way through doors thrust in his face. This girl is working her hands off to get out of this country so that she can get some sort of training.

There was Richard Brown. If he had been white he would have been alive today instead of dead of neglect. Many helped him when he asked but he was not the kind of boy that always asks. He was simply one who made colors sing.

There is a colored woman in Chicago who is a great musician. She thought she would like to study at Fontainebleau this summer where Walter Damrosch and a score of leaders of Art have an American school of music. But the application blank of this school says: “I am a white American and I apply for admission to the school.”

We can go on the stage; we can be just as funny as white Americans wish us to be; we can play all the sordid parts that America likes to assign to Negroes; but for any thing else there is still small place for us.

I first read this essay at least twenty years ago, but I swear I’ve thought about “when God makes a sculptor He does not always make the pushing sort of person who beats his way through doors thrust in his face” every day since. Every day. I think about it for black artists, for gay, lesbian, transgender, and queer artists, for women who put up with harassment and abuse from the very people who’ve promised to help them pursue their art. And I think about it even more when I think about the thousands if not millions of people who were turned away from ever becoming artists, writers, musicians, actors, sculptors, dancers, engineers, designers, programmers, or any other critical or creative field where doors are so often thrust in your face.

Yes, push through those doors. But hold them open after you. Because the next person, God may not have made to be one whose first inclination is to push.

All art, Du Bois argues, and in particular the art of black people, relies on not just Beauty, but Truth and Goodness, “goodness in all its aspects of justice, honor and right — not for sake of an ethical sanction but as the one true method of gaining sympathy and human interest.” Art that seeks to restore the balance of truth and goodness, on a subject like the lives of black people, which is prone to so much distortion and misunderstanding, necessarily relies on an ideal of Justice. This leads to maybe the most famous quote of the essay:

Thus all Art is propaganda and ever must be, despite the wailing of the purists. I stand in utter shamelessness and say that whatever art I have for writing has been used always for propaganda for gaining the right of black folk to love and enjoy. I do not care a damn for any art that is not used for propaganda. But I do care when propaganda is confined to one side while the other is stripped and silent.

What America is getting from its white artists, is propaganda that shames and distorts the lives of black people, in order to show them to be sinister and/or servile.

In other words, the white public today demands from its artists, literary and pictorial, racial pre-judgment which deliberately distorts Truth and Justice, as far as colored races are concerned, and it will pay for no other.

But respectability politics is almost as dangerous, when it comes to art.

On the other hand, the young and slowly growing black public still wants its prophets almost equally unfree. We are bound by all sorts of customs that have come down as second-hand soul clothes of white patrons. We are ashamed of sex and we lower our eyes when people will talk of it. Our religion holds us in superstition. Our worst side has been so shamelessly emphasized that we are denying we have or ever had a worst side. In all sorts of ways we are hemmed in and our new young artists have got to fight their way to freedom.

And here is the bind, the contradiction which even Du Bois cannot completely unravel. Until black artists produce great art, black people will not be registered by white people as fully human. And once those great artists appear, their blackness will be erased away, in favor of a false universality and sham humanism.

And then do you know what will be said? It is already saying. Just as soon as true Art emerges; just as soon as the black artist appears, someone touches the race on the shoulder and says, “He did that because he was an American, not because he was a Negro; he was born here; he was trained here; he is not a Negro — what is a Negro anyhow? He is just human; it is the kind of thing you ought to expect.”

I do not doubt that the ultimate art coming from black folk is going to be just as beautiful, and beautiful largely in the same ways, as the art that comes from white folk, or yellow, or red; but the point today is that until the art of the black folk compells [sic] recognition they will not be rated as human. And when through art they compell [sic] recognition then let the world discover if it will that their art is as new as it is old and as old as new.

Du Bois closes the essay with one of the most beautiful passages I’ve ever read. It’s also the most personal. It’s about his friend and classmate William Vaughan Moody.

I had a classmate once who did three beautiful things and died. One of them was a story of a folk who found fire and then went wandering in the gloom of night seeking again the stars they had once known and lost; suddenly out of blackness they looked up and there loomed the heavens; and what was it that they said? They raised a mighty cry: “It is the stars, it is the ancient stars, it is the young and everlasting stars!”

There are other great essays about the relationship between politics and art. Some of them are subtler than Du Bois’s. Some take on more directly the nature of politics or art itself. Some have a more politically radical intent. Some name more names, and pick more fights. But nobody but Du Bois, working with the economy he’s working with, states as directly the political problems facing art, artists, art critics, and the art-loving public. Nobody gets to the root of things as squarely as he does.

It’s the best essay on art and politics ever written. And if you don’t agree, I want to see your candidate. That’s all.

W.E.B. Du Bois was an American author, sociologist, historian, and activist. Apparently Du Bois was also a designer and design director of some talent as these hand-drawn infographics show.

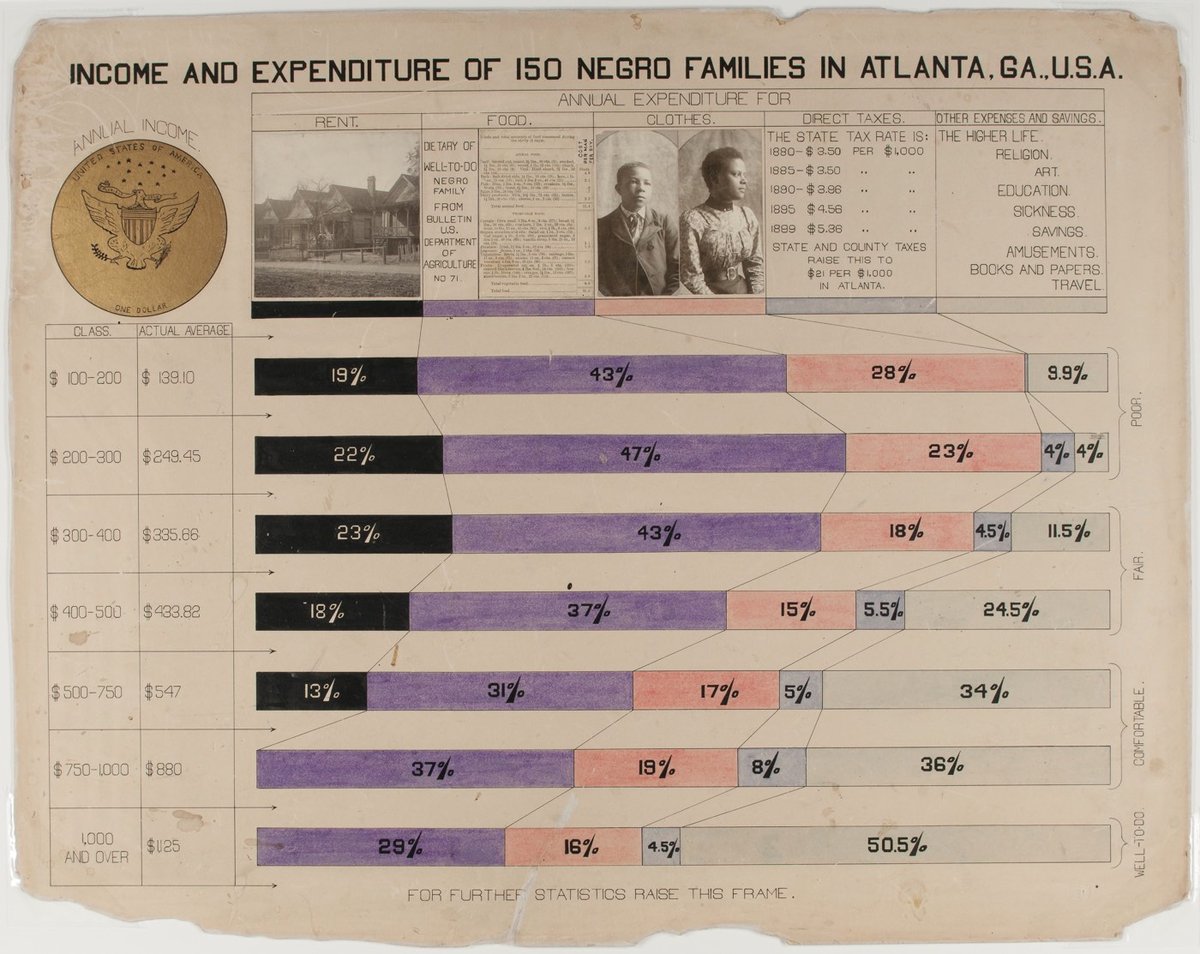

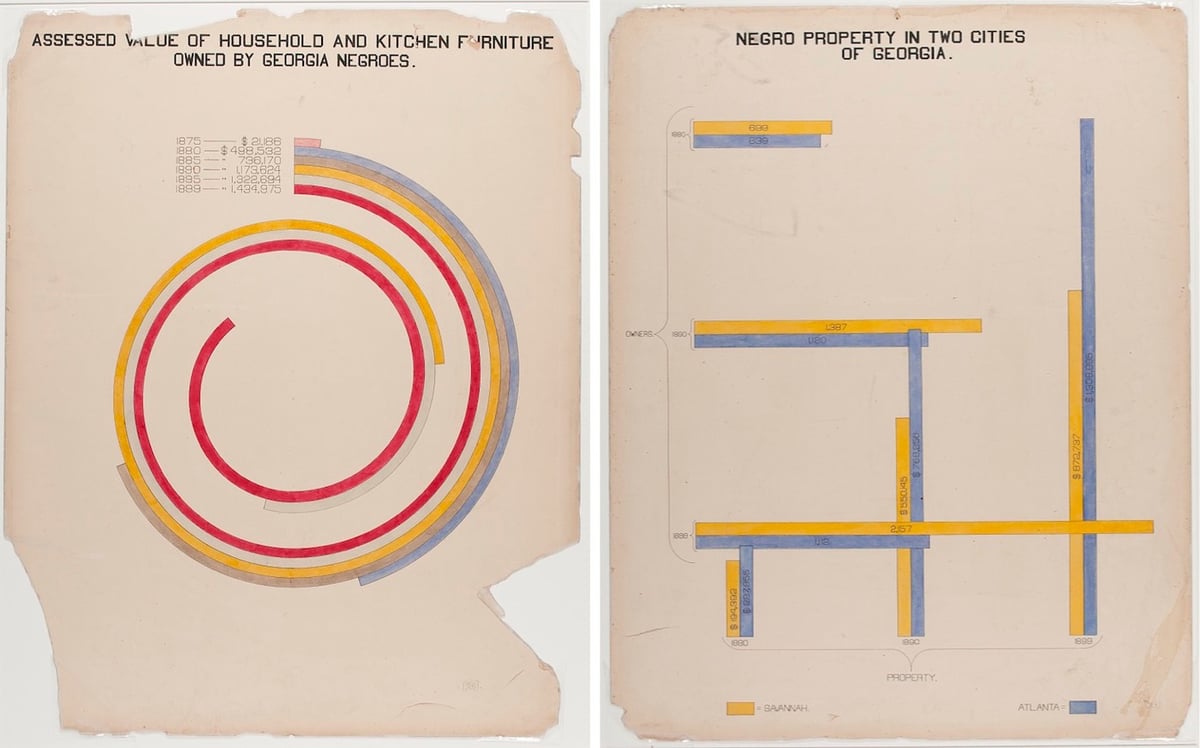

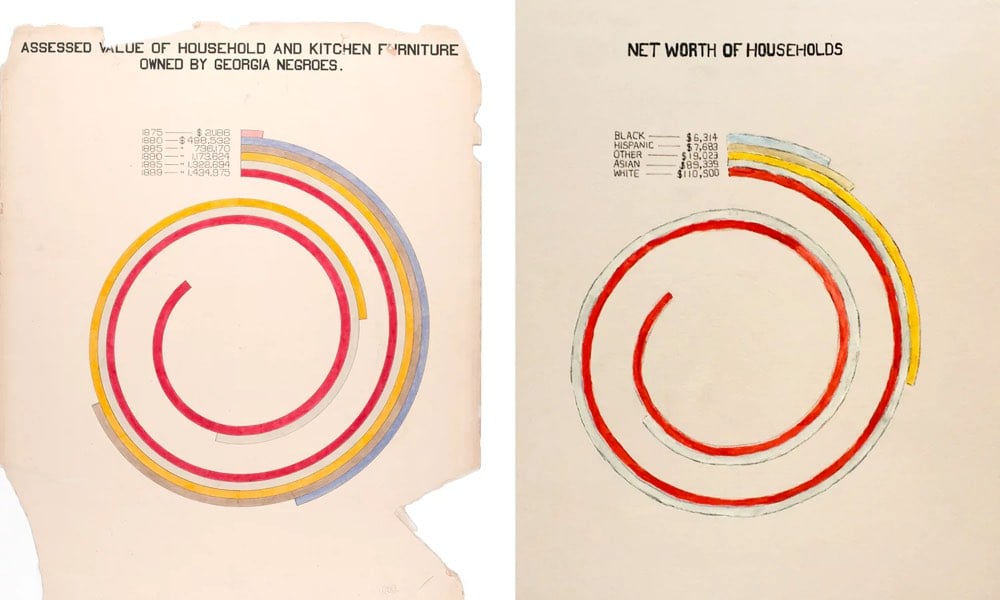

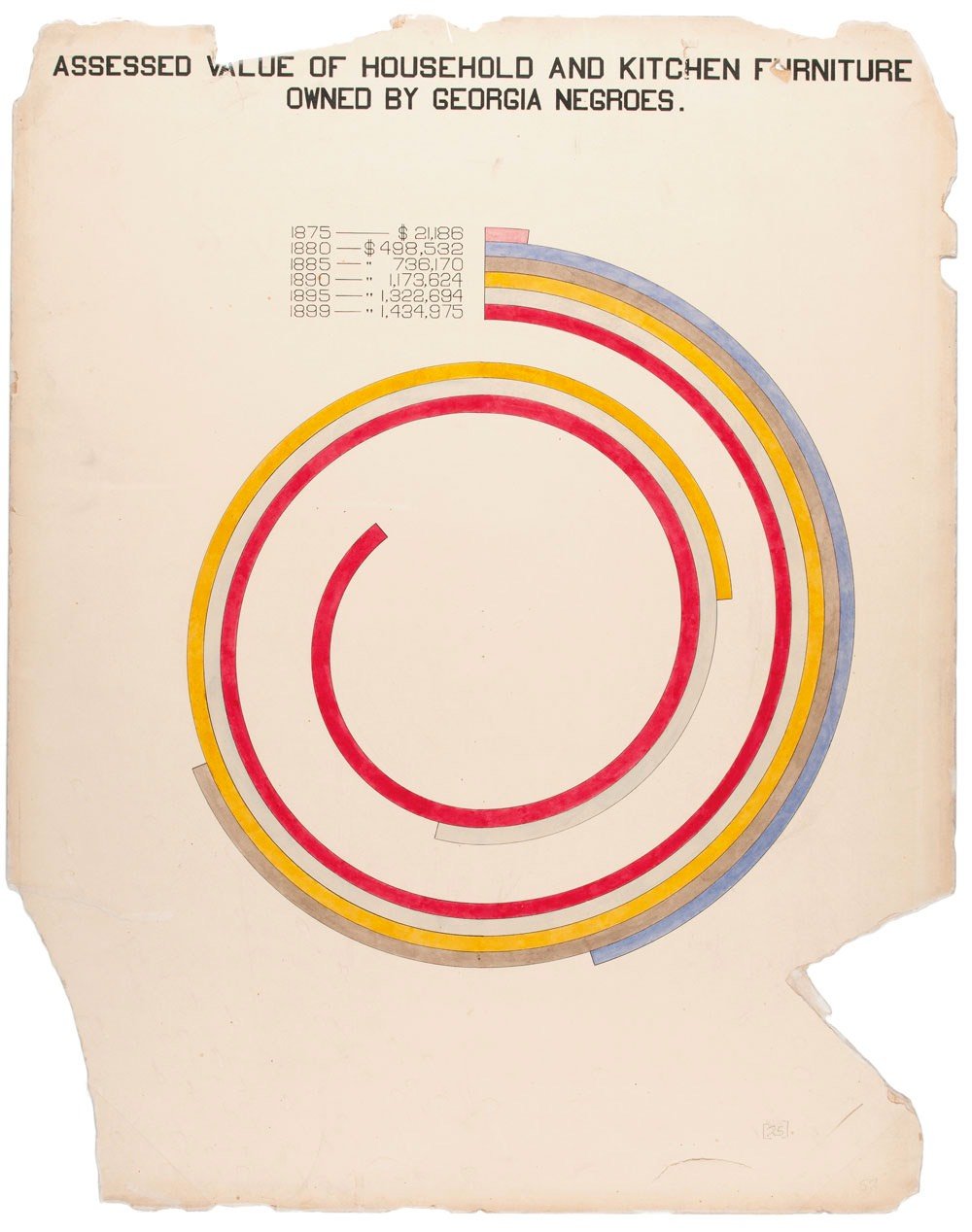

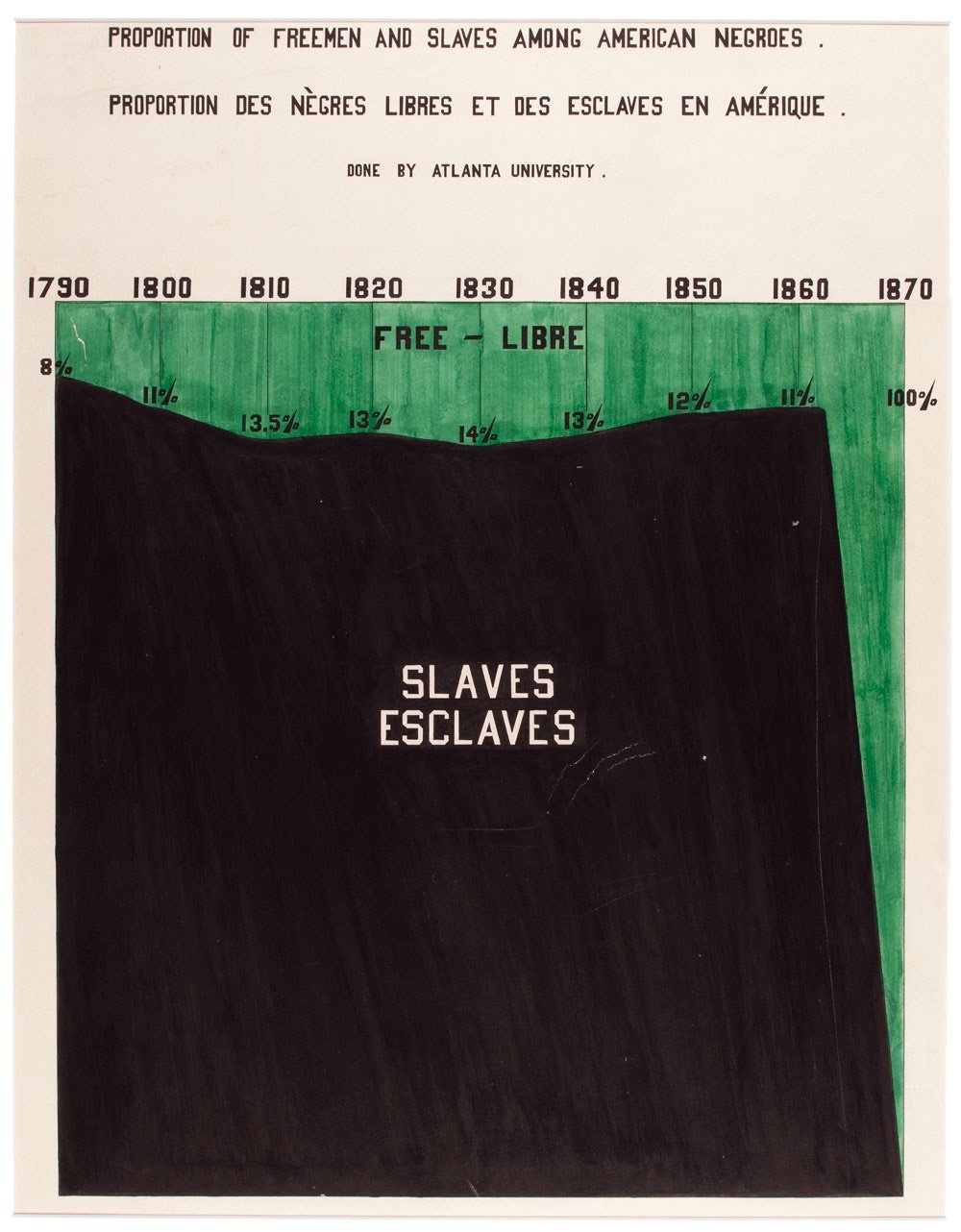

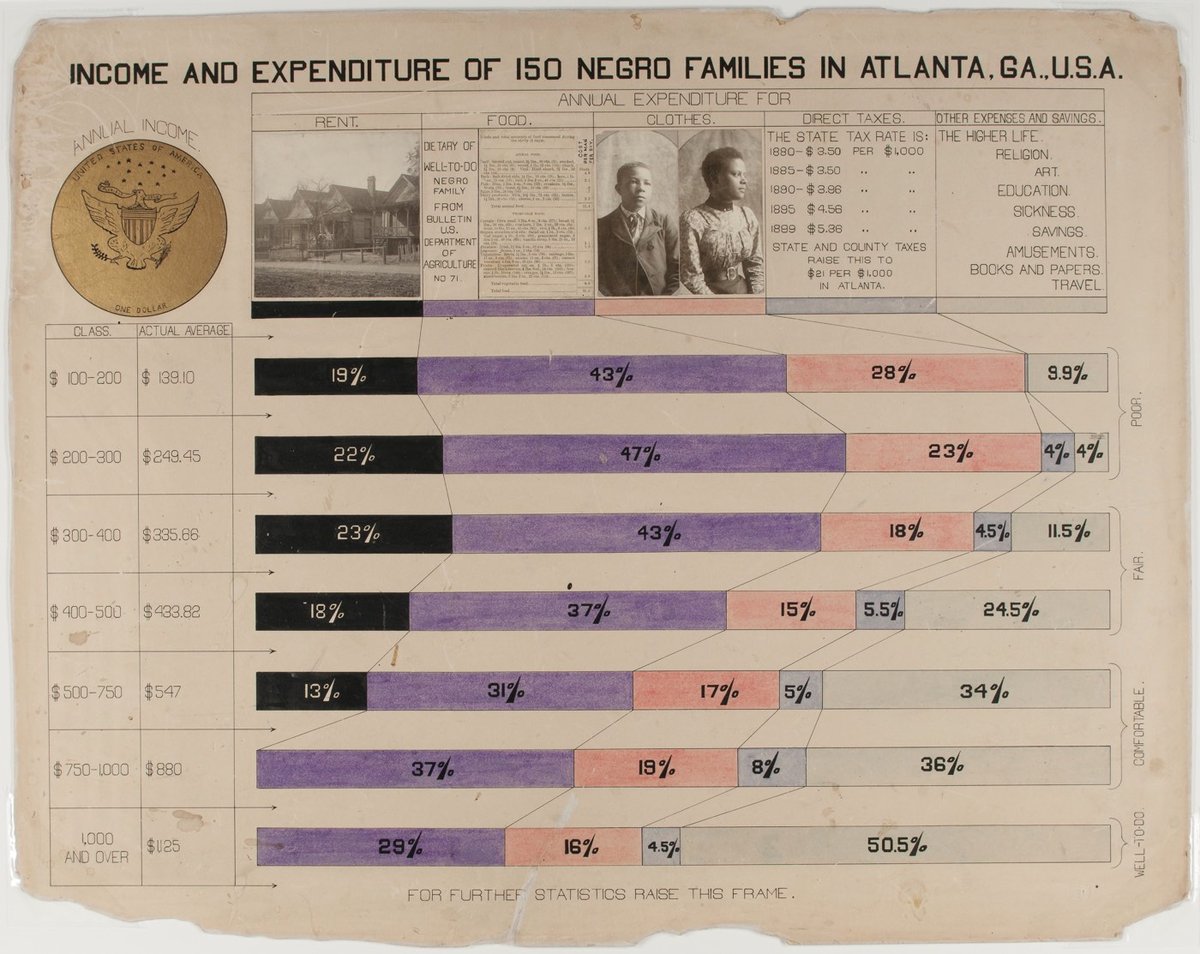

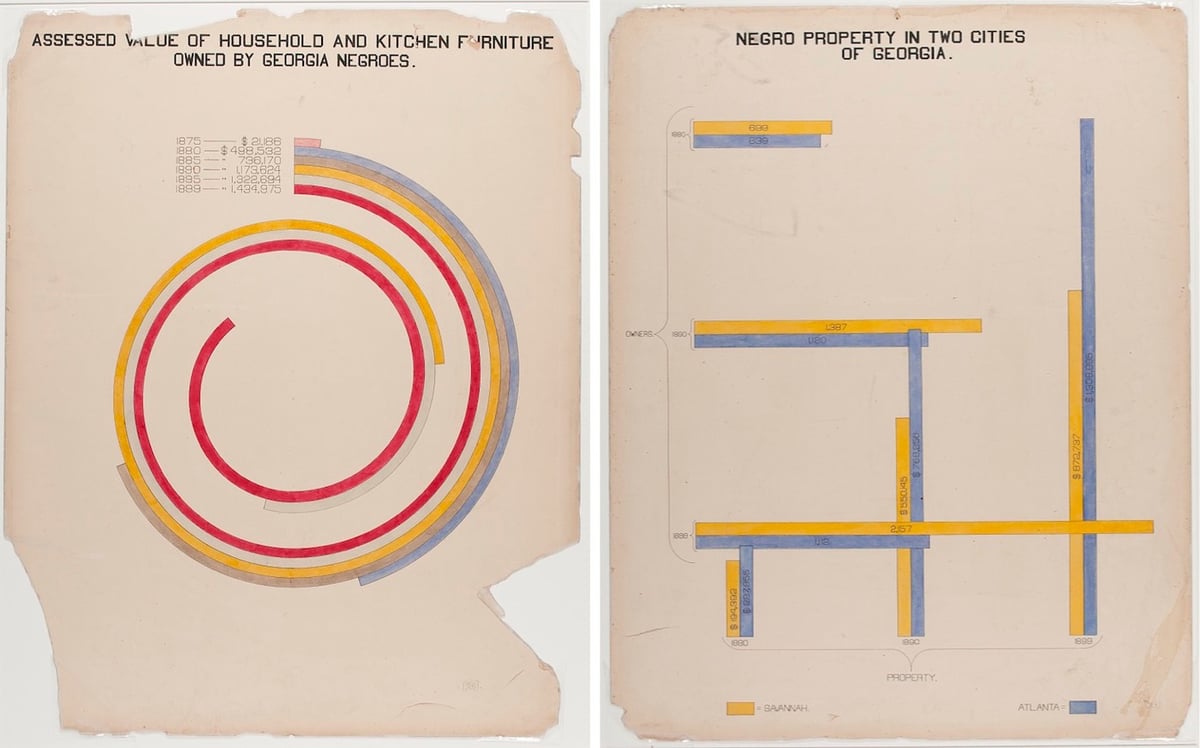

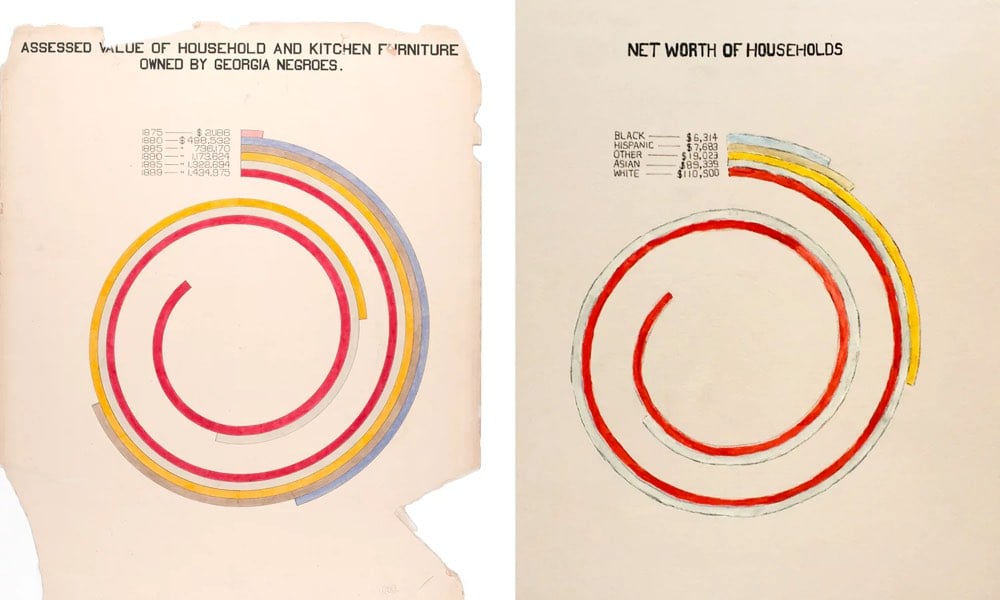

In addition to an extensive collection of photographs, four volumes containing 400 official patents by African Americans, more than 200 books penned by African-American authors, various maps, and a statuette of Frederick Douglass, the exhibition featured a total of fifty-eight stunning hand-drawn charts (a selection of which we present below). Created by Du Bois and his students at Atlanta, the charts, many of which focus on economic life in Georgia, managed to condense an enormous amount of data into a set of aesthetically daring and easily digestible visualisations. As Alison Meier notes in Hyperallergic, “they’re strikingly vibrant and modern, almost anticipating the crossing lines of Piet Mondrian or the intersecting shapes of Wassily Kandinsky”.

Update: Oh, this is great: Mona Chalabi has updated Du Bois’ charts with current data.

Wealth. If I had stayed close to the original chart, the updated version would have shown that in 2015, African American households in Georgia had a median income of about $36,655, which would fail to capture the story of inflation (net asset numbers aren’t published as cumulative for one race). Instead, I wanted to see how wealth varies by race in America today.

The story is bleak. I hesitated to use the word “worth”, but it’s the language used by the Census Bureau when they’re collecting this data and, since money determines so much of an individual’s life, the word seems relevant. For every dollar a black household in America has in net assets, a white household has 16.5 more.

Stay Connected