kottke.org posts about books

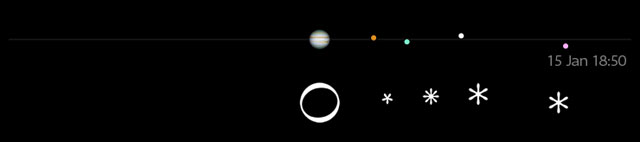

Paul Bogard recently published a book on darkness called The End of Night. Nicola Twilley and Geoff Manaugh interviewed Bogard about the book, the night sky, astronomy, security, cities, and prisons, among other things. The interview is interesting throughout but one of my favorite things is this illustration of the Bortle scale.

Twilley: It’s astonishing to read the description of a Bortle Class 1, where the Milky Way is actually capable of casting shadows!

Bogard: It is. There’s a statistic that I quote, which is that eight of every ten kids born in the United States today will never experience a sky dark enough to see the Milky Way. The Milky Way becomes visible at 3 or 4 on the Bortle scale. That’s not even down to a 1. One is pretty stringent. I’ve been in some really dark places that might not have qualified as a 1, just because there was a glow of a city way off in the distance, on the horizon. You can’t have any signs of artificial light to qualify as a Bortle Class 1.

A Bortle Class 1 is so dark that it’s bright. That’s the great thing-the darker it gets, if it’s clear, the brighter the night is. That’s something we never see either, because it’s so artificially bright in all the places we live. We never see the natural light of the night sky.

I can also recommend reading David Owen’s 2007 NYer piece on light pollution.

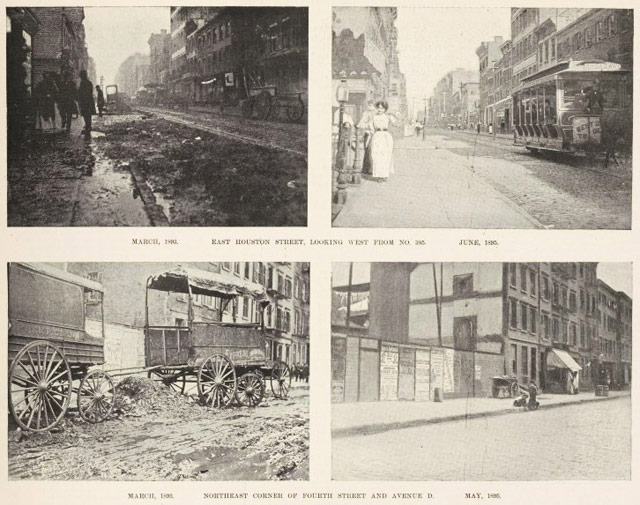

Robin Nagle, the Anthropologist in Residence for the New York City Department of Sanitation, recently wrote a book about the city’s sanitation department. Collectors Weekly has an interview with Nagle about the book and sanitation in general.

Waring also dressed the workers in white, and even his wife said, ‘What, are you crazy?’ But he wanted them to be associated with notions of hygiene. Of course, those in the medical profession wore white, and he understood, quite rightly, that it was an issue of public health and hygiene to keep the street clean. He also put them in the helmets that the police wore to signify authority, and they quickly were nicknamed the White Wings.

These men became heroes because, for the first time in anyone’s memory, they actually cleaned the city. It was a very bright day in the history of the department. Waring was only in office for three years, but after he left, nobody could use the old excuses that Tammany had used to dodge the issue of waste management. They had always said it was too crowded, with too many diverse kinds of people, and never mind that London and Paris and Philadelphia and Boston cleaned their streets. New York was different and it just couldn’t be done. Waring proved them wrong. Rates of preventable disease went down. Mortality rates went down. It also had a ripple effect across all different areas of the city.

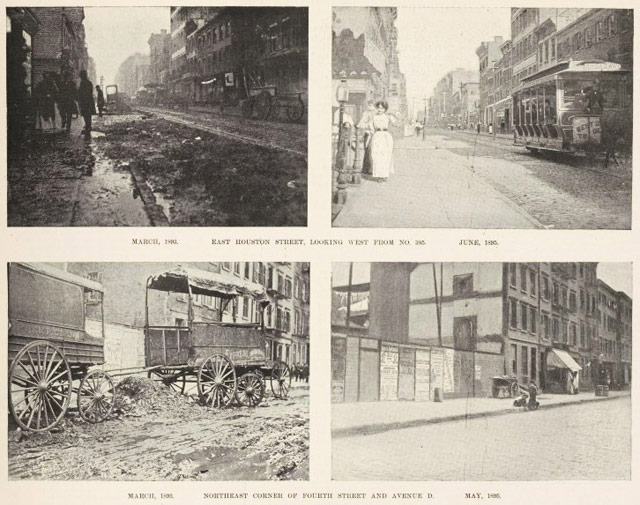

Now, NYC is not the cleanest city in the world, not by a long-shot, but it used to be so much worse. In the early 1890s, the streets were literally covered in trash because the Department of Street Cleaning (as it was known then) was so inept; look at the difference made by a 1895 reorganization of the department:

The book trailer for Thomas Pynchon’s new novel is either brilliant or the dumbest thing ever.

Fun fact: the phrase “I don’t even” was invented to react to this video. (via @GreatDismal)

I took a Greek and Roman literature class in college. Among the texts we studied was Lucretius’ On The Nature of Things. Shamefully, about the only thing I remembered from it was that the poem was an early articulation of the concept of atoms (see also Democritus). Impressive, chatting about atoms in 50 BCE. But reading Stephen Greenblatt’s The Swerve has reminded me what an impressive and prescient document it is, quite apart from its beauty as a poem. In chapter eight of his book, Greenblatt summarizes the main points of Lucretius’ poem:

Everything is made of invisible particles.

The elementary particles of matter — “the seeds of things” — are eternal.

The elementary particles are infinite in number but limited in shape and size.

All particles are in motion in an infinite void.

The universe has no creator or designer.

Everything comes into being as a result of a swerve.

[Ok, the swerve deserves a bit of explanation. Here’s Greenblatt:

If all the individual particles, in their infinite numbers, fell through the void in straight lines, pulled down by their own weight like raindrops, nothing would ever exist. But the particles do no move lockstep in a preordained single direction. Instead, “at absolutely unpredictable time and places they deflect slightly from their straight course, to a degree that could be described as no more than a shift of movement.” The position of the elementary particles is thus indeterminate.

I can’t help but think of quantum mechanics here. Anyway, back to the list.]

The swerve is the source of free will.

Nature ceaselessly experiments.

The universe was not created for or about humans.

Humans are not unique.

Human society began not in a Golden Age of tranquility and plenty, but in a primitive battle for survival.

The soul dies.

There is no afterlife.

Death is nothing to us.

All organized religions are superstitious delusions.

Religions are invariably cruel.

There are no angels, demons, or ghosts.

The highest goal of human life is the enhancement of pleasure and the reduction of pain.

The greatest obstacle to pleasure is not pain; it is delusion.

Understanding the nature of things generates deep wonder.

The seeds of atomic theory, quantum mechanics, evolution, agnosticism, atheism…they’re all right there, in a poem written by a man who died more than 2000 years ago.

If you’re at all interested in the Pioneer Anomaly (and you really should be, it’s fascinating), The Pioneer Detectives ebook by Konstantin Kakaes looks interesting.

Explore one of the greatest scientific mysteries of our time, the Pioneer Anomaly: in the 1980s, NASA scientists detected an unknown force acting on the spacecraft Pioneer 10, the first man-made object to journey through the asteroid belt and study Jupiter, eventually leaving the solar system. No one seemed able to agree on a cause. (Dark matter? Tensor-vector-scalar gravity? Collisions with gravitons?) What did seem clear to those who became obsessed with it was that the Pioneer Anomaly had the potential to upend Einstein and Newton — to change everything we know about the universe.

Kakaes was a science writer for The Economist and studied physics at Harvard, so this topic seems right up his alley. Available for $2.99 for the Kindle and for iBooks on iOS.

Sabine Heinlein follows several people through a post-prison jobs program to see how ex-convicts prepare for re-entry into the workforce.

In prison Angel thought that it wouldn’t be too hard to find a job once he got out. He believed he had come a long way. At eighteen he hadn’t been able to read or write. He wet his bed and suffered from uncontrollable outbursts of anger. At forty-seven he had studied at the college level. He told me he had read several thousand books. He earned numerous certificates while incarcerated — a Vocational Appliance Repair Certificate, a Certificate of Proficiency of Computer Operator, a Certificate in Library Training, an IPA (Inmate Program Assistant) II Training Certificate, and several welding certifications — but in the outside world these credentials counted for little.

“Irrelevant,” Angel said. “They might as well be toilet paper.”

This piece is the seventh chapter from Heinlein’s book, Among Murderers: Life After Prison.

In 2009, Dave Eggers published a book called Zeitoun, the story of a man and his family experiencing Hurricane Katrina and its aftermath.

Through the story of one man’s experience after Hurricane Katrina, Eggers draws an indelible picture of Bush-era crisis management. Abdulrahman Zeitoun, a successful Syrian-born painting contractor, decides to stay in New Orleans and protect his property while his family flees. After the levees break, he uses a small canoe to rescue people, before being arrested by an armed squad and swept powerlessly into a vortex of bureaucratic brutality. When a guard accuses him of being a member of Al Qaeda, he sees that race and culture may explain his predicament.

The story has taken an unexpected turn since its publication. The protagonist of the story, Abdulrahman Zeitoun, is currently on trial for the attempted first-degree murder of his wife.

Zeitoun made an offer: $20,000 to kill his ex-wife, Kathy, according to Pugh’s testimony. Zeitoun instructed Pugh, who was to be released soon from jail, to call Kathy Zeitoun — Zeitoun allegedly wrote her phone number on an envelope, which was introduced as evidence — and ask to see one of the family’s rental properties. When she took him to a certain property in Algiers, he could kill her there, he allegedly said. Zeitoun also allegedly told Pugh to buy a “throwaway phone” and take pictures to confirm she was dead.

(via digg)

Update: Zeitoun was found not guilty.

Abdulrahman Zeitoun was found not guilty Tuesday of trying to hire a hitman to kill his wife.

The verdict came from Orleans Parish Criminal District Court Judge Frank Marullo. Zeitoun, 55, had waived his right to a jury trial. He had been charged with solicitation of first-degree murder and attempted first-degree murder of his ex-wife. He was acquitted on both counts.

(thx, mike)

Details are scarce and publication is months away, but hotshot book designer Peter Mendelsund is coming out with a book called Cover. I bet it will contain a collection of his covers. Or will be about covers. Or something. But I love book covers so whatever it is, I am covered.

Even as a religious watcher of SNL in high school and into college, I had no idea Jack Handey was a real person until much later. So this profile of him comes in handy (ahem).

This idea — the notion of real jokes and the existence of pure comedy — came up again and again when I asked other writers about Handey. It seemed as if to them Handey is not just writing jokes but trying to achieve some kind of Platonic ideal of the joke form. “There is purity to his comedy,” Semple said. “His references are all grandmas and Martians and cowboys. It’s so completely free from topical references and pop culture that I feel like everyone who’s gonna make a Honey Boo Boo joke should do some penance and read Jack Handey.”

“For a lot of us, he was our favorite writer, and the one we were most in awe of,” said James Downey, who wrote for “S.N.L.” “When I was head writer there, my policy was just to let him do his thing and to make sure that nothing got in the way of him creating.”

“He was the purest writer,” Franken said. “It was pure humor, it wasn’t topical at all. It was Unfrozen Caveman Lawyer.”

Handey’s first novel is out today: The Stench of Honolulu. (via df)

Adapted from Brett Martin’s Difficult Men, this piece in Slate gives a glimpse of what it was like on the set of The Wire.

In the isolated hothouse of Baltimore, immersed in the world of the streets, the cast of The Wire showed a bizarre tendency to mirror its onscreen characters in ways that took a toll on its members’ outside lives: Lance Reddick, who played the ramrod-straight Lieutenant Cedric Daniels, tormented by McNulty’s lack of discipline, had a similarly testy relationship with West, who would fool around and try to make Reddick crack up during his camera takes. Gilliam and Lombardozzi, much like Herc and Carver, would spend the bulk of Seasons 2 and 3 exiled to the periphery of the action, stewing on stakeout in second-unit production and eventually lobbying to be released from their contracts.

Oh, McNutty. (thx, sam)

Malcolm Gladwell on economist Albert Hirschman, who embraced the roles of adversity, anxiety, and failure in creativity and success.

“The Principle of the Hiding Hand,” one of Hirschman’s many memorable essays, drew on an account of the Troy-Greenfield “folly,” and then presented an even more elaborate series of paradoxes. Hirschman had studied the enormous Karnaphuli Paper Mills, in what was then East Pakistan. The mill was built to exploit the vast bamboo forests of the Chittagong Hill Tracts. But not long after the mill came online the bamboo unexpectedly flowered and then died, a phenomenon now known to recur every fifty years or so. Dead bamboo was useless for pulping; it fell apart as it was floated down the river. Because of ignorance and bad planning, a new, multimillion-dollar industrial plant was suddenly without the raw material it needed to function.

But what impressed Hirschman was the response to the crisis. The mill’s operators quickly found ways to bring in bamboo from villages throughout East Pakistan, building a new supply chain using the country’s many waterways. They started a research program to find faster-growing species of bamboo to replace the dead forests, and planted an experimental tract. They found other kinds of lumber that worked just as well. The result was that the plant was blessed with a far more diversified base of raw materials than had ever been imagined. If bad planning hadn’t led to the crisis at the Karnaphuli plant, the mill’s operators would never have been forced to be creative. And the plant would not have been nearly as valuable as it became.

“We may be dealing here with a general principle of action,” Hirschman wrote, “Creativity always comes as a surprise to us; therefore we can never count on it and we dare not believe in it until it has happened. In other words, we would not consciously engage upon tasks whose success clearly requires that creativity be forthcoming. Hence, the only way in which we can bring our creative resources fully into play is by misjudging the nature of the task, by presenting it to ourselves as more routine, simple, undemanding of genuine creativity than it will turn out to be.”

Gladwell’s piece is based on Jeremy Adelman’s recent biography of Hirschman, Worldly Philosopher.

Here are pair of articles by Tom Standage, drawn from his forthcoming book on the 2,000-year history of social media, Writing on the Wall. In Share it like Cicero, Standage writes about how Roman authors used social networking to spread and publish their work.

One of the stories I tell in “Writing on the Wall” is about the way the Roman book-trade worked. There were no printing presses, so copying of books, which took the form of multiple papyrus rolls, was done entirely by hand, by scribes, most of whom were slaves. There were no formal publishers either, so Roman authors had to rely on word-of-mouth recommendations and social distribution of their works via their networks of friends and acquaintances.

In the late 1600s, a particularly effective social networking tool arose in England: the coffeehouse.

Like coffee itself, coffeehouses were an import from the Arab world. England’s first coffeehouse opened in Oxford in the early 1650s, and hundreds of similar establishments sprang up in London and other cities in the following years. People went to coffeehouses not just to drink coffee, but to read and discuss the latest pamphlets and news-sheets and to catch up on rumor and gossip.

Coffeehouses were also used as post offices. Patrons would visit their favorite coffeehouses several times a day to check for new mail, catch up on the news and talk to other coffee drinkers, both friends and strangers. Some coffeehouses specialized in discussion of particular topics, like science, politics, literature or shipping. As customers moved from one to the other, information circulated with them.

Standage previously wrote about the European coffeehouse in A History of the World in 6 Glasses.

An excerpt from Daniel Dennett’s new book, Intuition Pumps and Other Tools for Thinking, outlines seven of Dennett’s tools for thinking. His second tool is “respect your opponent”:

The best antidote I know for this tendency to caricature one’s opponent is a list of rules promulgated many years ago by social psychologist and game theorist Anatol Rapoport.

How to compose a successful critical commentary:

1. Attempt to re-express your target’s position so clearly, vividly and fairly that your target says: “Thanks, I wish I’d thought of putting it that way.”

2. List any points of agreement (especially if they are not matters of general or widespread agreement).

3. Mention anything you have learned from your target.

4. Only then are you permitted to say so much as a word of rebuttal or criticism.

In an essay that covers similar ground to Steven Johnson’s Where Good Ideas Come From, David Galbraith offers an interesting perspective on maximizing your creative potential.

I remember the very instant that I learned to be creative, to ‘invent’ things, to do things in an interesting and unusual way, and it happened by accident, literally.

I created mess around myself, the kind of chaos that would be very dangerous in an operating theater but which is synonymous with artists’ studios, and in that mess I edited the accidents. By increasing the amount of mess I had freed things up and increased the possibilities, I had maximised the adjacent possible and was able to create the appearance of inventing new things by editing the mistakes which appeared novel and interesting.

The adjacent possible is one of those ideas that, once you hear it, you want to apply to everything around you.

In a book called Three Felonies A Day, Boston civil rights lawyer Harvey Silverglate says that everyone in the US commits felonies everyday and if the government takes a dislike to you for any reason, they’ll dig in and find a felony you’re guilty of.

The average professional in this country wakes up in the morning, goes to work, comes home, eats dinner, and then goes to sleep, unaware that he or she has likely committed several federal crimes that day. Why? The answer lies in the very nature of modern federal criminal laws, which have exploded in number but also become impossibly broad and vague. In Three Felonies a Day, Harvey A. Silverglate reveals how federal criminal laws have become dangerously disconnected from the English common law tradition and how prosecutors can pin arguable federal crimes on any one of us, for even the most seemingly innocuous behavior. The volume of federal crimes in recent decades has increased well beyond the statute books and into the morass of the Code of Federal Regulations, handing federal prosecutors an additional trove of vague and exceedingly complex and technical prohibitions to stick on their hapless targets. The dangers spelled out in Three Felonies a Day do not apply solely to “white collar criminals,” state and local politicians, and professionals. No social class or profession is safe from this troubling form of social control by the executive branch, and nothing less than the integrity of our constitutional democracy hangs in the balance.

In response to a question about what happens to big company CEOs who refuse to go along with government surveillance requests, John Gilmore offers a case study in what Silverglate is talking about.

We know what happened in the case of QWest before 9/11. They contacted the CEO/Chairman asking to wiretap all the customers. After he consulted with Legal, he refused. As a result, NSA canceled a bunch of unrelated billion dollar contracts that QWest was the top bidder for. And then the DoJ targeted him and prosecuted him and put him in prison for insider trading — on the theory that he knew of anticipated income from secret programs that QWest was planning for the government, while the public didn’t because it was classified and he couldn’t legally tell them, and then he bought or sold QWest stock knowing those things.

This CEO’s name is Joseph P. Nacchio and TODAY he’s still serving a trumped-up 6-year federal prison sentence today for quietly refusing an NSA demand to massively wiretap his customers.

You combine this with the uber-surveillance allegedly being undertaken by the NSA and other governmental agencies and you’ve got a system for more or less automatically accusing any US citizen of a felony. Free society, LOL ROFLcopter.

Update: For the past two years, the Wall Street Journal has been “examining the vastly expanding federal criminal law book and its consequences”. (thx, jesse)

From a passage of Kurt Vonnegut’s Bluebeard, the three types of specialists needed for the success of any revolution.

Slazinger claims to have learned from history that most people cannot open their minds to new ideas unless a mind-opening team with a peculiar membership goes to work on them. Otherwise, life will go on exactly as before, no matter how painful, unrealistic, unjust, ludicrous, or downright dumb that life may be.

The team must consist of three sorts of specialists, he says. Otherwise the revolution, whether in politics or the arts or the sciences or whatever, is sure to fail.

The rarest of these specialists, he says, is an authentic genius — a person capable of having seemingly good ideas not in general circulation. “A genius working alone,” he says, “is invariably ignored as a lunatic.”

The second sort of specialist is a lot easier to find: a highly intelligent citizen in good standing in his or her community, who understands and admires the fresh ideas of the genius, and who testifies that the genius is far from mad. “A person like this working alone,” says Slazinger, “can only yearn loud for changes, but fail to say what their shapes should be.”

The third sort of specialist is a person who can explain everything, no matter how complicated, to the satisfaction of most people, no matter how stupid or pigheaded they may be. “He will say almost anything in order to be interesting and exciting,” says Slazinger. “Working alone, depending solely on his own shallow ideas, he would be regarded as being as full of shit as a Christmas turkey.”

Slazinger, high as a kite, says that every successful revolution, including Abstract Expressionism, the one I took part in, had that cast of characters at the top — Pollock being the genius in our case, Lenin being the one in Russia’s, Christ being the one in Christianity’s.

He says that if you can’t get a cast like that together, you can forget changing anything in a great big way.

(via @moleitau)

In this morning’s NY Times, Angelina Jolie writes about her decision to have a preventive double mastectomy to hopefully ward off cancer.

My mother fought cancer for almost a decade and died at 56. She held out long enough to meet the first of her grandchildren and to hold them in her arms. But my other children will never have the chance to know her and experience how loving and gracious she was.

We often speak of “Mommy’s mommy,” and I find myself trying to explain the illness that took her away from us. They have asked if the same could happen to me. I have always told them not to worry, but the truth is I carry a “faulty” gene, BRCA1, which sharply increases my risk of developing breast cancer and ovarian cancer.

It happens that just last night I read about the BRCA-1 gene in Siddhartha Mukhergee’s excellent biography of cancer, The Emperor of All Maladies. This part is right near the end of the book:

Like cancer prevention, cancer screening will also be reinvigorated by the molecular understanding of cancer. Indeed, it has already been. The discovery of the BRCA genes for breast cancer epitomizes the integration of cancer screening and cancer genetics. In the mid-1990s, building on the prior decade’s advances, researchers isolated two related genes, BRCA-1 and BRCA-2, that vastly increase the risk of developing breast cancer. A woman with an inherited mutation in BRCA-1 has a 50 to 80 percent chance of developing breast cancer in her lifetime (the gene also increases the risk for ovarian cancer), about three to five times the normal risk. Today, testing for this gene mutation has been integrated into prevention efforts. Women found positive for a mutation in the two genes are screened more intensively using more sensitive imaging techniques such as breast MRI. Women with BRCA mutations might choose to take the drug tamoxifen to prevent breast cancer, a strategy shown effective in clinical trials. Or, perhaps most radically, women with BRCA mutations might choose a prophylactic mastectomy of both breasts and ovaries before cancer develops, another strategy that dramatically decreases the chances of developing breast cancer.

Radical is an understatement…what a tough and brave decision to make. Again from the book, I liked this woman’s take on it:

An Israeli woman with a BRCA-1 mutation who chose this strategy after developing cancer in one breast told me that at least part of her choice was symbolic. “I am rejecting cancer from my body,” she said. “My breasts had become no more to me than a site for my cancer. They were of no more use to me. They harmed my body, my survival. I went to the surgeon and asked him to remove them.”

The genetic testing company 23andme screens for three common types of mutation in the BRCA1 or BRCA2 genes:

Five to 10 percent of breast cancers occur in women with a genetic predisposition for the disease, usually due to mutations in either the BRCA1 or BRCA2 genes. These mutations greatly increase not only the risk for breast cancer in women, but also the risk for ovarian cancer in women as well as prostate and breast cancer among men. Hundreds of cancer-associated BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations have been documented, but three specific BRCA mutations are worthy of note because they are responsible for a substantial fraction of hereditary breast cancers and ovarian cancers among women with Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry. The three mutations have also been found in individuals not known to have Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry, but such cases are rare.

23andme testing kits are only $99.

Update: Two things. First, and I hope this isn’t actually necessary because you are all intelligent people who can read things and make up your own minds, but let me just state for the official record that you should never never never never NEVER take medical advice, inferred or otherwise, from celebrities or bloggers. Come on, seriously. If you’re concerned, go see a doctor.

Two: I have no idea what the $99 23andme test covers with regard to BRCA1 and BRCA2 gene mutations beyond what the company states. The most comprehensive test for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations was developed by a company called Myriad Genetics and costs about $3000. Myriad has patented the genes, a decision that has been sharply criticized and is currently being decided by the Supreme Court.

But many doctors, patients and scientists aren’t happy with the situation.

Some are offended by the very notion that a private company can own a patent based on a gene that was invented not by researchers in a lab but by Mother Nature. Every single cell in every single person has copies of the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes.

Myriad officials say they deserves the patent because they invested a great deal of money to figure out the sequence and develop “synthetic molecules” based on that sequence that can be used to test the variants in a patient.

“We think it is right for a company to be able to own its discoveries, earn back its investment, and make a reasonable profit,” the company wrote on its blog.

I do know the 23andme test covers something related to the BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations…a friend of a friend did the 23andme test, tested positive for the BRCA1 mutation, and decided to have a preventive double mastectomy after consulting her doctor and further tests. (thx, mark, allison, and ★spavis)

We all know that art forgeries are just cheap rip-offs of real art. What Jonathan Keats’ new book presupposes is, maybe they’re not?

Forgers are the foremost artists of our age.

I’m not talking about the objects they make. Their real art is to con us into accepting the works as authentic. They do so, inevitably, by finding our blind spots, and by exploiting our common-sense assumptions. When they’re caught (if they’re caught), the scandal that ensues is their accidental masterpiece. Learning that we’ve been defrauded makes us anxious — much more so than any painting ever could — provoking us to examine our poor judgment. This effect is inescapable, since we certainly didn’t ask to be duped. A forgery is more direct, more powerful, and more universal than any legitimate artwork.

See also Uncreative Writing, fake is the new real, even if it’s fake it’s real, and this paragraph from Joe Posnanski’s piece on pitching phenoms:

You have to understand that to a boy of the 1970s, the line between comic books and real life people was hopelessly blurred. Was Steve Austin, the Six Million Dollar Man, real or fake? Fake? Well, then, how about Evel Knievel jumping over busses on his motorcycle? Oh, he was real. The Superman ads said, “You will believe a man can fly,” and Fonzie started jukeboxes by simply hitting them, and Elvis Presley wore capes, and Nolan Ryan threw pitches 102 mph, and Roger Staubach (who they called Captain America) kept bringing the Cowboys back from certain defeat, and Muhammad Ali let George Foreman tire himself out by leaning against the ropes and taking every punch he could throw. What was real anyway?

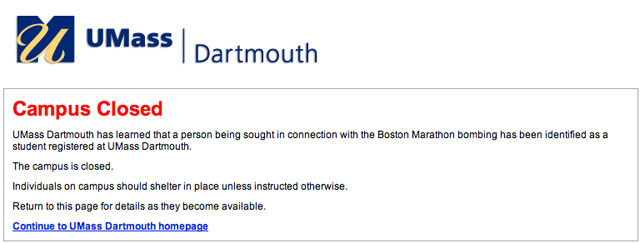

James Surowiecki, the author of The Wisdom of Crowds, wrote about what was right and wrong about Reddit’s crowdsourced hunt for the Boston bombing suspects.

The truth is that if Reddit is actually interested in using the power of its crowd to help the authorities, it needs to dramatically rethink its approach, because the process it used to try to find the bombers wasn’t actually tapping the wisdom of crowds at all — at least not as I would define that wisdom. For a crowd to be smart, the people in it need to be not only diverse in their perspectives but also, relatively speaking, independent of each other. In other words, you need people to be thinking for themselves, rather than following the lead of those around them.

When the book came out in 2004, I wrote a short post that summarizes the four main conditions you need for a wise crowd. What’s striking about most social media and software, as Surowiecki notes in the case of Reddit, is how most of these conditions are not satisfied. There’s little diversity and independence: Twitter and Facebook mostly show you people who are like you and things your social group is into. And social media is becoming ever more centralized: Facebook, Twitter, Tumblr, Medium, Pinterest, etc. instead of a decentralized network of independent blogs. In fact, the nature of social media is to be centralized, peer-dependent, and homogeneous because that’s how people naturally group themselves together. It’s a wonder the social media crowd ever gets anything right.

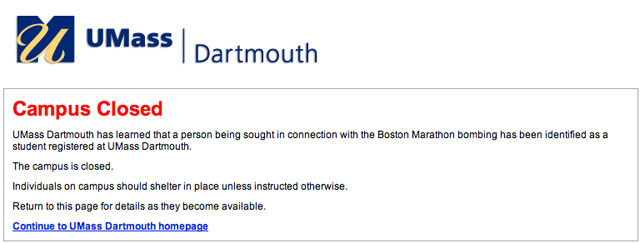

UMass Dartmouth is reporting that “a person being sought in connection with the Boston Marathon bombing has been identified as a student registered at UMass Dartmouth”:

I don’t know that there’s any verified report that registered student is bombing suspect Dzhokhar Tsarnaev, but I found a blog post from August 2011 that suggests that Tsarnaev was participating in the school’s summer reading program for incoming first-year students. The students were participating in a group discussion blog while reading Malcolm Gladwell’s Blink: The Power of Thinking Without Thinking. The post in question was written by UMass Dartmouth English teacher Shelagh Smith on the concept of thin-slicing as it pertained to the case of the West Memphis Three. The post reads, in part:

I believe that thin slicing put them in jail. It helped an entire community make a rash decision and justify their actions in convicting three teens of murder. Once the town was able to identify the bogeyman, they could rest easy again.

But it all went horribly wrong. The real murderers were never found. These young men went into prison at 18 years old. Today, they walked out at 36 years old.

Being different - being unique - is a right we’re supposed to enjoy in this country. But what we can’t control is how people view us.

So what do we do about that? Is there anything we can do about it?

In response, a commenter listing his name as “Dzhokhar Tsarnaev” posted the following about a week and a half after the original posting:

In this case it would have been hard to protect or defend these young boys if the whole town exclaimed in happiness at the arrest. Also, to go against the authorities isn’t the easiest thing to do. Don’t get me wrong though, I am appalled at the situation but I think that the town was scared and desperate to blame someone. It’s because of stories like this and such occurrences that make a positive change in this world. I’m pretty sure there won’t be anymore similar tales like this. In any case, if they do, people won’t stand quiet, i hope.

Tsarnaev also made another comment in another thread on the blog a few minutes earlier in which he offered a critique of Gladwell’s book:

While I understand and agree with most of the concepts that Gladwell explained in his book, there are several ideas of his that I cannot fathom or just choose not to believe. Yes, this book was very interesting but the idea that a person can predict whether you and your partner are going to be together in the future is honestly a little hard to believe. Sure, if you put two obvious celebrities in a room talking about how they’re going to adopt six children, that’s just not going to work out. And the idea that a more experienced doctor is more likely to be sued is likely to happen because they would have way more patients and more time in the work force. “Thin-slicing” and other concepts made me want to keep reading.

I’m currently reading The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of Cancer (which is excellent) and I’m up to the chapters on prevention, specifically the prevention of lung cancer through reduction of cigarette smoking. I had no idea cigarette smoking was so uncommon in the US as recently as 1870…but we caught up quickly.

In 1870, the per capita consumption in America was less than one cigarette per year. A mere thirty years later, Americans were consuming 3.5 billion cigarettes and 6 billion cigars every year. By 1953, the average annual consumption of cigarettes had reached thirty-five hundred per person. On average, an adult American smoked ten cigarettes every day, an average Englishman twelve, and a Scotsman nearly twenty.

For some context on that 3500/yr per person number (and the unbelievable 7000/yr Scottish rate), the current rate in the US is around 1000/yr and the highest current rate in the world is in Serbia at almost 2900/yr per person.

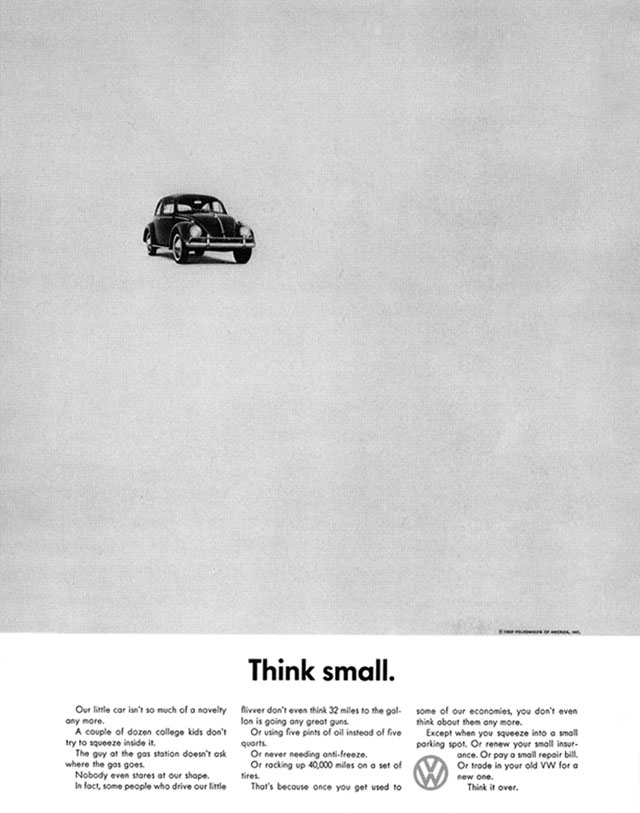

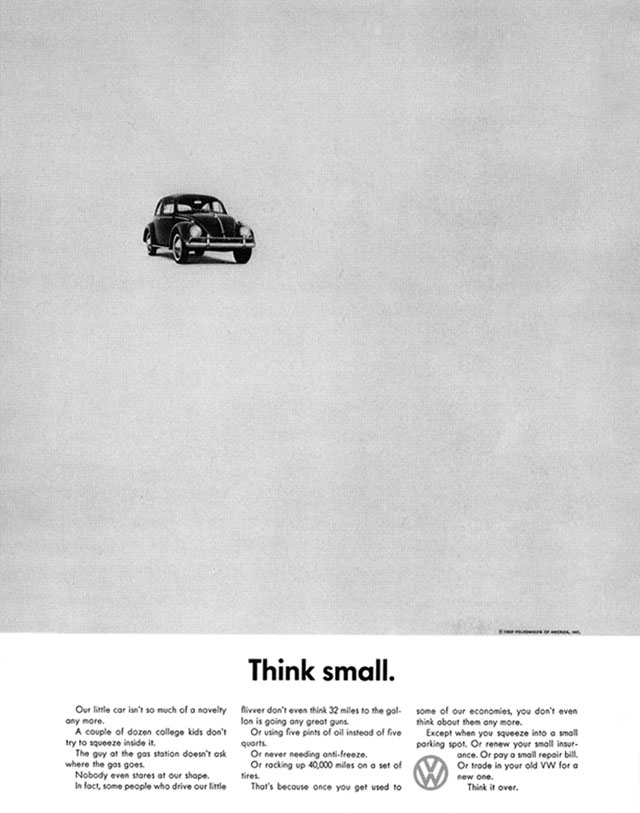

If the advertising parts of Mad Men are your favorite bits of the show, might I recommend Taschen’s two-volume Mid-Century Ads (on Amazon).

It’s a beautiful set of books, tons of ads from the 50s and 60s presented in large format.

Excerpted from a book called The Art of Making Magazines, a piece on how fact-checking works at the New Yorker.

So that was the old New Yorker. The biggest difference between David Remnick’s New Yorker today and the Shawn New Yorker is timeliness. During the Shawn years, book reviews ran months, even years out of sync with publication dates. Writers wrote about major issues without any concern for news pegs or what was going on in the outside world. That was the way people thought, and it was really the way the whole editorial staff was tuned.

All this changed when Tina Brown arrived. Whereas before, editorial schedules were predictable for weeks or a month in advance, under Tina we began getting 8,000-, 10,000-, 12,000-word pieces in on a Thursday that were to close the following Wednesday. But something else changed in a way that is more important. Prior to Tina, the magazine really had been writer-driven, and I think this is why they gave the writers so much liberty. They wanted the writers to develop their own, often eccentric, interests.

Under Tina, writing concepts began to originate in editors’ meetings, and assignments were given out to writers who were essentially told what to write. And a lot of what the editors wanted was designed to be timely and of the moment and tended to change from day to day. So the result was that we were working on pieces that were really much more controversial and much less well-formulated than anything we had dealt with previously, and often we would put teams of checkers to work on these pieces and checking and editing could go on all night.

This looks beautiful: A Map of the World is a collection of maps by illustrators and storytellers. I’ve featured at least a few of the maps in the book here on kottke.org. Here’s a sample:

You can see more of the maps in the book on the publisher’s web site. (via raul, who says “This book is insanely beautiful. Buy it if you love maps. It will make you happy.”)

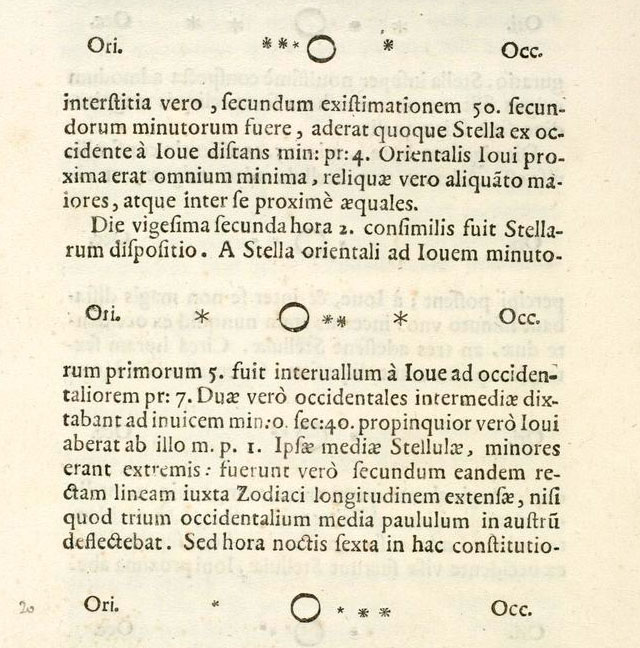

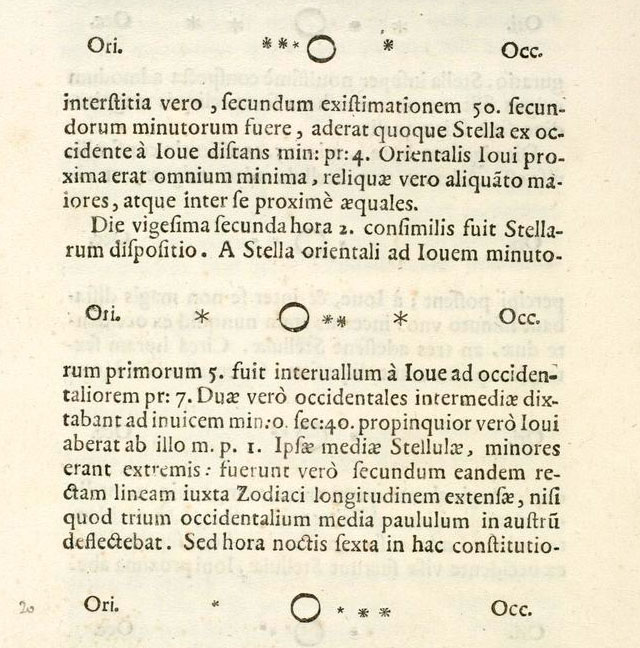

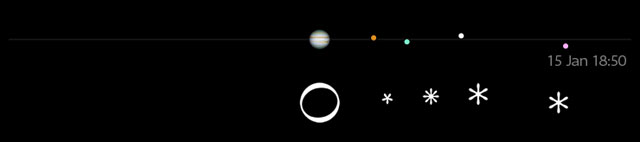

In the pages of Sidereus Nuncius, Galileo described the four large moons of Jupiter in a series of 64 sketches which looked a lot like ASCII art in the text:

Using an online tool for computing the positions of Jupiter’s moons, Ernie Wright compared Galileo’s sketches to the moons’ actual motions.

Click through for an animated GIF of all the comparisons. Not bad for the telescopic state of the art in 1610. For a taste of how celestial objects actually appeared when viewed through Galileo’s telescope, check out this video starting around 7:30. (thx, john)

This story by Kevin Guilfoile about his aging father (who worked for the Pirates and the Baseball Hall of Fame) and the mystery of what happened to the bat that Roberto Clemente got his 3,000th hit with is one of my favorite things that I’ve read over the past few months.

[My father’s] personality is present, if his memories are a jumble. He is still funny, and surprisingly quick with one-liners to crack up the staff at the facility where he lives. He is exceedingly polite, same as he ever was. He is good at faking a casual conversation, especially on the phone. But if you sit and talk with him for a long time, he gets very anxious. He starts tapping his forehead with his fingers. “Shouldn’t we be going?” he’ll say. You tell him there’s no place we need to be, but 30 seconds later he’ll ask again, “Shouldn’t we be going?”

What happens to memories when they’re collapsed inside time like this? They don’t exactly disappear, they just become impossible to unpack. And so my father, who loved stories so much — who loved to tell them, who loved to hear them — can no longer comprehend them. The structure of any story, after all, is that this happened and then that happened, and he can’t make sense of any sequence.

That is the real hell of this disease. His own identity has become a puzzle he can’t solve.

Objects have stories, too. Puzzles that need to be solved. Like a pair of baseball bats, for instance, that each passed through Roberto Clemente’s hands before they passed through my father’s. One hung on my bedroom wall throughout my childhood. The other is in the Baseball Hall of Fame.

These objects never forget, but they never tell their stories, either.

Without a little bit of luck, we’d never hear them.

Or more than a little luck:

My father has lots of old baseball bats given to him by players he worked with over the years. He has Mickey Mantle bats from his years with the Yankees, and Willie Stargell and Dave Parker bats from his days with the Pirates. The one I always loved best was an Adirondack model with R CLEMENTE embossed in modest block letters, instead of the usual signature burned into the barrel. On the bottom of the knob, Roberto had written a tiny “37” in ballpoint pen, presumably to indicate its weight: 37 ounces. It also had a series of scrapes around the middle where someone had scratched off the trademark stripe that encircled all Adirondack bats. Former Pirates GM Joe Brown gave my dad this bat several years after Roberto died. For much of my childhood it hung on the wall of my bedroom, on a long rack with about a dozen other game-used bats.

My dad had been working at the Hall of Fame for more than a decade when, in 1993, his old friend Tony Bartirome, a one-time Pirates infielder who had become their longtime trainer, came to Cooperstown for a visit. Tony and his wife went to dinner with my folks and then came back to our house to chat. The only way to go to the first-floor washroom in that house was through my old bedroom, and on a trip there, Tony noticed that Adirondack of Clemente’s hanging on the wall.

Tony carried it into the living room. He said to Dad, “Where did you get this bat?” My dad told him that Joe Brown had given him the bat as a gift, sometime in the late ’70s. “Bill,” Tony said. “This is the bat Roberto used to get his 3,000th hit.”

My father was confused by this. “That’s impossible,” he told Tony. “The day he hit 3,000 I went down to the clubhouse, and Roberto himself handed me the bat he used. I sent it to the Hall of Fame. I walk by it every day.”

“Well,” Tony said. “I have a story to tell you.”

It’s a wonderful story, read the whole thing. Or get the book: the story is excerpted from Guilfoile’s A Drive into the Gap, available here or for the Kindle.

Matt Kahn is reading every bestselling novel from each of the past 100 years.

For this blog I plan, among other things, to read and review every novel to reach the number one spot on Publishers Weekly annual bestsellers list, starting in 1913. Beyond just a book review, I’m going to provide some information on the authors and the time at which these books were written in an attempt to figure out just what made these particular books popular at that particular time.

A few things. The Silmarillion?! Was the top selling book in 1977? John Grisham appears on the list 11 different times; the guy is a machine. And it’s interesting to see when popularity and critical acclaim part ways, when the Roths, le Carrés, and E.L. Doctorows give way to the Clancys, Grishams, and Dan Browns.

According to Penguin’s year-end financial report, Thomas Pynchon’s next novel will deal with “Silicon Alley between dotcom boom collapse and 9/11”. The title is Bleeding Edge.

Nassim Taleb asserts that, on average, old technologies have longer life expectancies than younger technologies, which helps explain why books are still around and CD-ROM magazines aren’t.

For example: Let’s assume the sole information I have about a gentleman is that he is 40 years old, and I want to predict how long he will live. I can look at actuarial tables and find his age-adjusted life expectancy as used by insurance companies. The table will predict he has an extra 44 years to go; next year, when he turns 41, he will have a little more than 43 years to go.

For a perishable human, every year that elapses reduces his life expectancy by a little less than a year.

The opposite applies to non-perishables like technology and information. If a book has been in print for 40 years, I can expect it to be in print for at least another 40 years. But — and this is the main difference — if it survives another decade, then it will be expected to be in print another 50 years.

This is adapted from Taleb’s recent book, Antifragile. Anyone read this yet? I really liked The Black Swan.

Newer posts

Older posts

Stay Connected