kottke.org posts about climate crisis

A new video from Kurzgesagt is designed to provide a little hope that humans can figure a way out of the climate crisis, without being overly pollyannish.

And so for many the future looks grim and hopeless. Young people feel particularly anxious and depressed. Instead of looking ahead to a lifetime of opportunity they wonder if they will even have a future or if they should bring kids into this world. It’s an age of doom and hopelessness and giving up seems the only sensible thing to do.

But that’s not true. You are not doomed. Humanity is not doomed.

There’s been progress in the last decade, in terms of economics, technology, policy, and social mores. It’s not happening fast enough to limit warming to 1.5°C, but if progress continues, gains accumulate, people keep pushing, and politicians start to figure out where the momentum is heading, we can get things under control before there’s a global apocalypse.

The winning entries in the Environmental Photographer of the Year for 2021 highlight the ways in which our planet’s climate is changing and how humans are (and are not) adapting to those changes. From top to bottom, photos by Kevin Ochieng Onyango, Simone Tramonte, and Michele Lapini. (via dense discovery)

Temperature Textiles are knitted textiles like blankets, scarves, and socks with patterns drawn from climate crisis indicators like temperature, sea level rise, and CO2 emissions. See also Global Warming Blankets. (via colossal)

While indigenous communities, farmers, and those living close to the land have known for generations the role that beavers play in maintaining healthy ecosystems, more and more scientists have been experimenting and gathering data on just how essential these animals are. Through their actions, beaver (and humans mimicking their actions) can help restore river-based ecosystems, improve wildfire resilience, bring fish & other animals back to habitats, and fight drought.

Beaver should be our national climate action plan because connected floodplains store water, store carbon, improve water quality, improve the resilience to wildfire, and what beaver do play an enormous role in controlling the dynamics of those systems. So, yeah, it sounds really trite to give a national climate action plan to some rodents. But if we don’t do that directly, we should at least be trying to mimic what they do.

The video above provides a great overview on what we’re learning about how beavers restore ecosystems. Last month, I linked to this Sacramento Bee piece about how beavers were used to revitalize a dry California creek bed:

The creek bed, altered by decades of agricultural use, had looked like a wildfire risk. It came back to life far faster than anticipated after the beavers began building dams that retained water longer.

“It was insane, it was awesome,” said Lynnette Batt, the conservation director of the Placer Land Trust, which owns and maintains the Doty Ravine Preserve.

“It went from dry grassland… to totally revegetated, trees popping up, willows, wetland plants of all types, different meandering stream channels across about 60 acres of floodplain,” she said.

The Doty Ravine project cost about $58,000, money that went toward preparing the site for beavers to do their work.

In comparison, a traditional constructed restoration project using heavy equipment across that much land could cost $1 to $2 million, according to Batt.

See also The Beaver Manifesto and this long piece from Places Journal about beavers as environmental engineers.

Across North America and Europe, public agencies and private actors have reintroduced beavers through “re-wilding” initiatives. In California and Oregon, beavers are enhancing wetlands that are critical breeding habitat for salmonids, amphibians, and waterfowl. In Nevada, Utah, and New Mexico, environmental groups have partnered with ranchers and farmers to encourage beaver activity on small streams. Watershed advocates in California are leading a campaign to have beavers removed from the state’s non-native species list, so that they can be managed as a keystone species rather than a nuisance. And federal policy is shifting, too. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service sees beavers as “partners in restoration,” and the Forest Service has supported efforts like the Methow Beaver Project, which mitigates water shortages in North Central Washington. Since 2017, the USDA Natural Resource Conservation Service has funded beaver initiatives through its Aquatic Restoration Program.

(via the kid should see this)

A group of researchers, scientists, and artists is building an Earth’s Black Box in a remote area of Tasmania that will function like a flight data recorder for climate change, recording the potential crash of our civilization.

Earth’s Black Box will record every step we take towards this catastrophe. Hundreds of data sets, measurements, and interactions relating to the health of our planet will be continuously collected and safely stored for future generations.

The purpose of the device is to provide an unbiased account of the events that lead to the demise of the planet, hold accountability for future generations, and inspire urgent action.

In a quote to the NY Times, one of the project’s participants said, “I’m on the plane; I don’t want it to crash.”

Artist Rogan Brown is highlighting what the climate crisis is doing to global coral populations with two recent delicate and intricate paper sculptures of bleached coral. Brown writes:

Here I try to capture the beauty, intricacy and fragility of the coral reef in layers of simple paper. The world’s coral reefs have become symbols of the devastating effects of global warming and man-made pollution. Mass bleaching events occur each year with increasing regularity and if the situation continues then it is inevitable that we will witness the demise of these magnificent biodiverse habitats. My hope is that by reminding us of how astonishing these ecosystems are we may unite to save them.

You can check out the rest of Brown’s intricate paper sculptures in his portfolio or on Instagram. (via colossal)

Since 2003, photographer Olaf Otto Becker has been documenting the decline of the glaciers and ice sheet in Greenland.

Greenland’s ice sheet is melting. Regularly, like the ticking of a clock, huge, new icebergs from the edges of the glacier plunge into the ocean each day with a thunderous boom and a roar. Our planet breathes. The accelerated melting of the ice is nothing more than one of our Earth’s compensatory reactions. Everything is constantly in motion. Even landscapes are changing with breathtaking speed, if time is not measured on a human scale. For me, icebergs are swimming sculptures, witnesses to a global change that, drifting southward on the ocean, slowly dissolve into their mirror image.

I’ve included some of my favorite shots from his projects above — beautiful but signifiers of the deep trouble humanity is in. (via colossal)

For the last ten years, artist Amy Balkin has been collecting artifacts related to the climate crisis. The collection is called A People’s Archive of Sinking and Melting.

A People’s Archive of Sinking and Melting is a collection of materials contributed by people living in places that may disappear because of the combined physical, political, and economic impacts of climate change, primarily sea level rise, erosion, desertification, and glacial melting.

From a piece about the archive in the New Yorker:

There is an incredible pathos to Balkin’s collection of things. In the light of imagined future eyes, tinged by loss, all manner of things become relevant that would otherwise pass unnoticed. Even two beer-bottle caps, in this context, are mesmerizing. Both are from places that are threatened with a certain kind of disappearance, or, at the very least, radical change; through their corrosion and fading, they seemed to foretell this disappearance somehow. And yet, paradoxically, looking at them, I knew that these pieces of metal would likely outlast me. A future person might see them in a museum, displayed with a label that reads “Beer-bottle caps, common in this time.” But what would that person’s world be like? What would be lost, between now and then, even as these fragments are shored up against ruin?

You can contribute to the archive — instructions for sending in an artifact are here.

Because of humans, most of the world’s oyster reefs have disappeared over the last 200 years. Now, some groups around the world are trying to put some of them back. In addition to providing water filtration and habitats for other animals, offshore oyster reefs can help slow long-term erosion by acting as living breakwater structures that partially deflect waves during storm surges.

In the last century, 85% of the world’s oyster reefs have vanished. And we’re only recently beginning to understand what that’s cost us: While they don’t look incredibly appealing from the shore, oysters are vital to bays and waterways around the world. A single oyster can filter up to 50 gallons of water every day. And over time, oysters form incredible reef structures that double as habitats for various species of fish, crabs, and other animals. In their absence, our coastlines have suffered.

Now, several projects from New York to the Gulf of Mexico and Bangladesh are aiming to bring the oysters back. Because not only are oysters vital ecosystems; they can also protect us from the rising oceans by acting as breakwaters, deflecting waves before they hit the shore. It won’t stop the seas from rising — but embracing living shorelines could help protect us from what’s to come.

(via the kid should see this)

Update: Check out the Billion Oyster Project if you’d like to get involved in returned oysters to New York Harbor. (via @djacobs)

One of the many effects of human-driven climate change is that, on average, the bodies of animals are getting smaller — birds, fish, deer, frogs, rodents, insects. And these changes could have large and unpredictable consequences.

“That’s the problem with human-driven climate change. It’s the rate of change that’s just orders of magnitude faster than what the natural world has had to deal with in the past. Size is really important to survival, and you can’t just change that indefinitely without consequence. For one thing, I don’t think it’s feasible that species are going to be able to continue to get smaller and maintain things like a migration from one hemisphere to another.”

And since smaller bodies can hold fewer eggs, they result in fewer offspring, and a lower population size in the long run. For amphibians who need to keep their skin wet in order to breathe, shrinking can mean higher chances of drying out in a drought because their bodies absorb and hold smaller quantities of water.

But the more concerning consequences have to do with how this could destabilize relationships between species. Because shrinking plays out at different rates for different species, predators might have to eat more and more of shrinking prey, for example, throwing a finely-tuned ecosystem off balance.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has released their summary report on the climate emergency, which warns that our climate is now changing rapidly almost everywhere and immediate & massive action is necessary. The press release starts:

Scientists are observing changes in the Earth’s climate in every region and across the whole climate system, according to the latest Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Report, released today. Many of the changes observed in the climate are unprecedented in thousands, if not hundreds of thousands of years, and some of the changes already set in motion — such as continued sea level rise — are irreversible over hundreds to thousands of years.

However, strong and sustained reductions in emissions of carbon dioxide (CO2) and other greenhouse gases would limit climate change. While benefits for air quality would come quickly, it could take 20-30 years to see global temperatures stabilize, according to the IPCC Working Group I report, Climate Change 2021: the Physical Science Basis, approved on Friday by 195 member governments of the IPCC, through a virtual approval session that was held over two weeks starting on July 26.

This is a huge deal — all 195 member governments had to approve the findings and language in this report and the report is not ambiguous. From Eric Holthaus:

The report’s main takeaway, put in a single sentence directly quoted from the report’s press release: “Unless there are immediate, rapid and large-scale reductions in greenhouse gas emissions, limiting warming to close to 1.5°C or even 2°C will be beyond reach.”

That means “immediate, rapid, large-scale” change is what we MUST demand — there’s a vastly limited future for all of us if it doesn’t happen right away.

The most striking part of the report to me is its of use the word “rapid” prominently, which to me is a major change from past reports.

The era of rapid climate change has begun. Both a rapid escalation of consequences, and a rapid escalation of solutions. Time has run out for anything but radical change.

To me, the report is equal parts depressing and galvanizing.

It will take several years, even in the best possible scenario, to see the positive effects of rapidly reductions in emissions. But that’s not so different from every other worthwhile investment we make — from going to school, to going to therapy, to building bike lanes, to forming communities of mutual aid. Every worthwhile thing takes time. And, if we believe this report, the next 20-30 years is the most important time of our whole lives.

In this video, Tomorrow’s Build takes a look at the $7 billion flood defense system that was built to protect Venice, Italy from increased flooding due to climate change. They detail how the system was built, how well it works, how it compares with other defense systems, the challenges associated with keeping it working, and how well this sort of defense system might work for other coastal cities (NYC, SF, Sydney).

In what will be an increasingly common occurrence in the years to come, smoke from fires in the western United States and Canada covered a large part of the US over the past few days. The smoke drifted thousands of miles to the eastern seaboard and turned the skies hazy, the Sun orange, and the air dangerous for some people to breathe. But there’s good news: your Covid mask works for air pollution too!

Dr. Commane said people should avoid going outdoors in high-pollution conditions, and especially avoid strenuous exercise. She also suggested that wearing filtered masks can provide protection for those who can’t avoid the outdoors.

“A lot of the masks people have been wearing for Covid are designed to capture PM2.5,” she said, referring to N95-style masks. “That’s the right size to be very useful for air quality.”

It’s always nice when your apocalyptic dystopias match up so nicely.

Sarah Miller, author of this 2019 article on Miami real estate & rising oceans, recently wrote this resonant piece, All The Right Words On Climate Have Already Been Said.

I told her I didn’t have anything to say about climate change anymore, other than that I was not doing well, that I was miserable. “I am so unhappy right now.” I said those words. So unhappy. Fire season was not only already here, I said, but it was going to go on for at least four more months, and I didn’t know what I was going to do with myself. I didn’t know how I would stand the anxiety. I told her I felt like all I did every day was try to act normal while watching the world end, watching the lake recede from the shore, and the river film over, under the sun, an enormous and steady weight.

There’s only one thing I have to say about climate change, I said, and that’s that I want it to rain, a lot, but it’s not going to rain a lot, and since that’s the only thing I have to say and it’s not going to happen, I don’t have anything to say.

Miller continued:

Also, for what? Let’s give the article (the one she was starting to maybe think about asking me to write that I was wondering if I could write) the absolute biggest benefit of the doubt and imagine that people read it and said, “Wow, this is exactly how I feel, thanks for putting it into words.”

What then? What would happen then? Would people be “more aware” about climate change? It’s 109 degrees in Portland right now. It’s been over 130 degrees in Baghdad several times. What kind of awareness quotient are we looking for? What more about climate change does anyone need to know? What else is there to say?

This is where I am on the climate emergency most days now (and nearly there on the pandemic). Really, what the fuck else is there to say?

From Electric Vehicles Won’t Save Us by Coby Lefkowitz:

This isn’t a story about Elon Musk, or Tesla, or a contrarian take about how “oil is good, actually.” I unconditionally support electric vehicles in their quest to take over the primacy of gasoline-powered vehicles in the market. But I don’t save that enthusiasm for their prospects on society broadly. From the perspective of the built environment, there is nothing functionally different between an electric vehicle and a gasoline propelled one. The relationship is the same, and it’s unequivocally destructive. Cars, however they’re powered, are environmentally cataclysmic, break the tethers of community, and force an infrastructure of dependency that is as financially ruinous to our country as it is dangerous to us as people. In order to build a more sustainable future and a better world for humanity, we need to address the root problems that have brought us to where we so perilously lie today.

For this video, the NY Times talked to several people from around the world (Britain, Zimbabwe, Norway, India, etc.) about what they think about how the United States is approaching climate change and other environmental challenges. Spoiler alert: there is a lot of incredulity about how shitty America is doing in this area. And that matters because what happens here affects everyone around the world.

See also What Does U.S. Health Care Look Like Abroad? and What Do U.S. Elections Look Like Abroad?

Writing in the New Yorker and citing a report by Carbon Tracker Initiative, Bill McKibben provides some hope that we can address the climate crisis.

Titled “The Sky’s the Limit,” it begins by declaring that “solar and wind potential is far higher than that of fossil fuels and can meet global energy demand many times over.” Taken by itself, that’s not a very bold claim: scientists have long noted that the sun directs more energy to the Earth in an hour than humans use in a year. But, until very recently, it was too expensive to capture that power. That’s what has shifted — and so quickly and so dramatically that most of the world’s politicians are now living on a different planet than the one we actually inhabit. On the actual Earth, circa 2021, the report reads, “with current technology and in a subset of available locations we can capture at least 6,700 PWh p.a. [petawatt-hours per year] from solar and wind, which is more than 100 times global energy demand.” And this will not require covering the globe with solar arrays: “The land required for solar panels alone to provide all global energy is 450,000 km2, 0.3% of the global land area of 149 million km2. That is less than the land required for fossil fuels today, which in the US alone is 126,000 km2, 1.3% of the country.” These are the kinds of numbers that reshape your understanding of the future.

But world governments will need to invest in renewable energy sooner rather than later and fossil fuel companies will fight tooth and nail to slow the transition to renewables. If they win in slow-walking the response to the climate crisis, as McKibben puts it, “no one will have an ice cap in the Arctic, either, and everyone who lives near a coast will be figuring out where on earth to go”.

In his latest impeccably produced video, Neil Halloran looks at the science of climate change and uncertainty both in science and in the public’s trust of science.

Degrees of Uncertainty is an animated documentary about climate science, uncertainty, and knowing when to trust the experts. Using cinematic visualizations, the film travels through 20,000 years of natural temperature changes before highlighting the rapid warming of the last half century.

The vast majority of climate scientists seem pretty sure that human use of fossil fuels has warmed the Earth and that warming is increasingly having an impact on both nature and society. But how do we, as members of the public with a relatively poor understanding of science, evaluate how certain we should be?

FYI: This video includes some interactive elements that only work if you watch it on Halloran’s website.

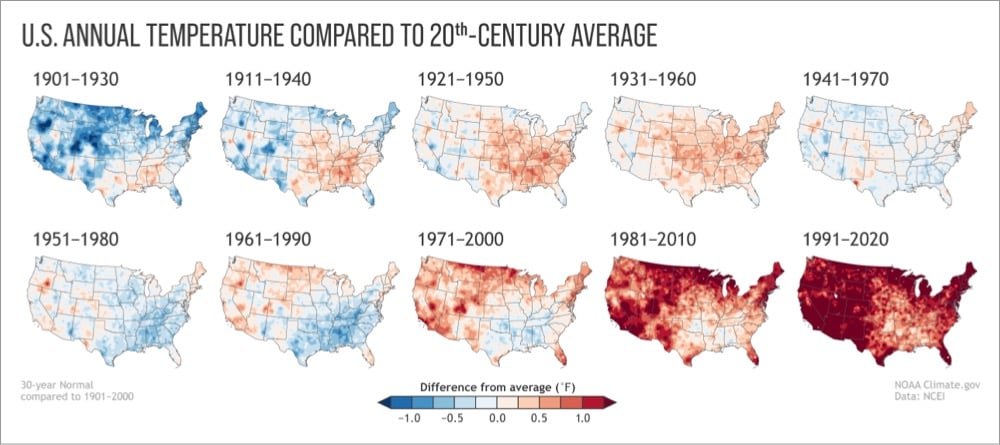

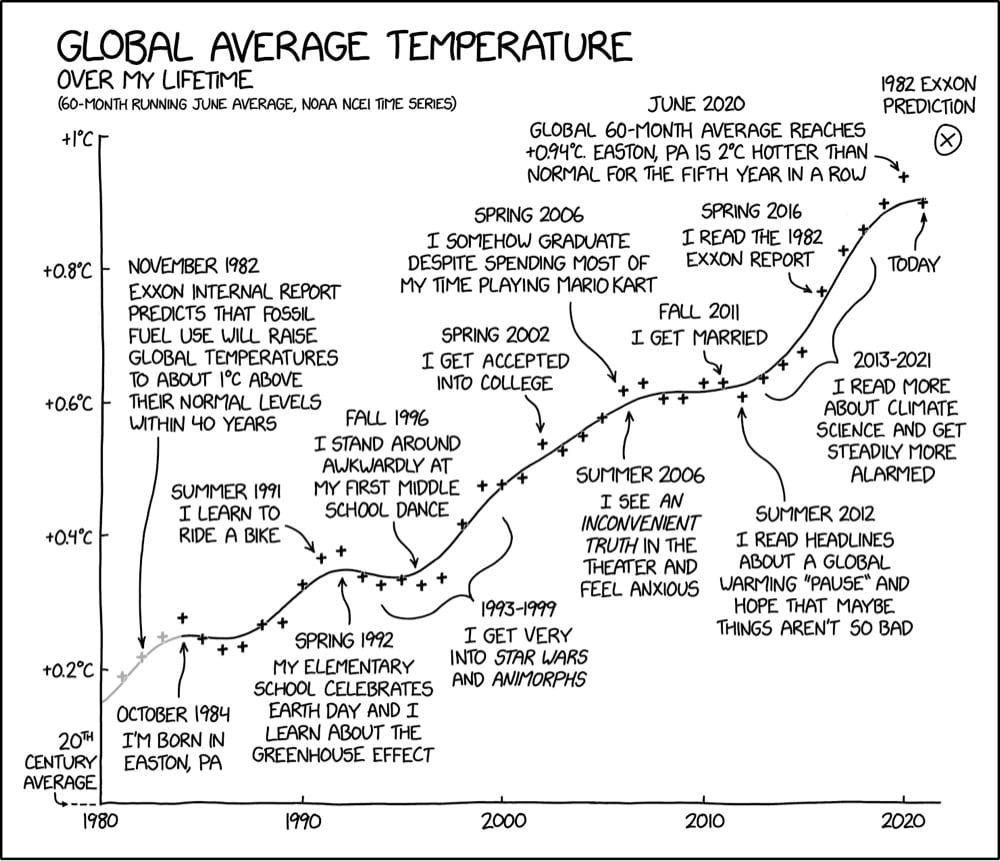

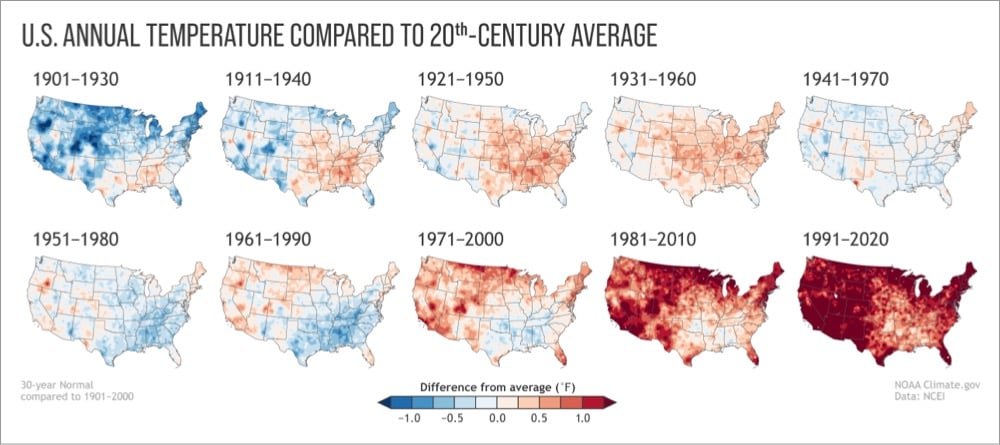

Every 10 years, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) updates its definition of what it defines as “normal” weather.

As soon as the 2021 New Year’s celebrations were over, the calls and questions started coming in from weather watchers: When will NOAA release the new U.S. Climate Normals? The Normals are 30-year averages of key climate observations made at weather stations and corrected for bad or missing values and station changes over time. From the daily weather report to seasonal forecasts, the Normals are the basis for judging how temperature, rainfall, and other climate conditions compare to what’s normal for a given location in today’s climate.

They’re set to release the updated 1991-2020 Normals in early May and, crucially, these new normal climate conditions are not adjusted for climate change.

The last update of the Normals took place in 2011, when the baseline shifted from 1971-2000 to 1981-2010. Among the highlights of the rollout was the creation of a map showing how climate-related planting zones across the contiguous United States had shifted northward in latitude and upward in elevation. It was a clear signal that normal overnight low temperatures across the country were warmer than they used to be.

The planting zone maps emphasized a key point about the Normals and climate change: the once-per-decade update means these products gradually come to reflect the “new normal” of climate change caused by global warming. What’s normal today is often very different than what was normal 50 or 100 years ago. This gradual adjustment is the point: the purpose of the Normals is to provide context on what climate is like today, not how it’s changing over time.

This is literally shifting baselines in action.

So what are shifting baselines? Consider a species of fish that is fished to extinction in a region over, say, 100 years. A given generation of fishers becomes conscious of the fish at a particular level of abundance. When those fishers retire, the level is lower. To the generation that enters after them, that diminished level is the new normal, the new baseline. They rarely know the baseline used by the previous generation; it holds little emotional salience relative to their personal experience.

And so it goes, each new generation shifting the baseline downward. By the end, the fishers are operating in a radically degraded ecosystem, but it does not seem that way to them, because their baselines were set at an already low level.

Over time, the fish goes extinct — an enormous, tragic loss — but no fisher experiences the full transition from abundance to desolation. No generation experiences the totality of the loss. It is doled out in portions, over time, no portion quite large enough to spur preventative action. By the time the fish go extinct, the fishers barely notice, because they no longer valued the fish anyway.

I’ve been thinking a lot about shifting baselines recently — specifically in terms of how quickly people in the US got used to thousands of people dying from Covid every day and became unwilling to take precautions or change behaviors that were deemed essential just months earlier when many fewer people were dying. See also mass shootings.

Greta Thunberg took a year off of school to travel the world to better understand the changing planet, a journey captured in this three-part BBC series set to debut on PBS this Thursday (April 22, aka Earth Day). I found out about this from Lizzie Widdicombe’s short profile of Thunberg in the New Yorker.

Thunberg is on the autism spectrum, and the film illustrates how the condition lends a unique moral clarity to her activism. “I don’t follow social codes,” she said. “Everyone else seems to be playing a role, just going on like before. And I, who am autistic, I don’t play this social game.” She eschews empty optimism. Her over-all reaction to the coronavirus pandemic is to compare it with her cause: “If we humans would actually start treating the climate crisis like a crisis, we could really change things.”

Her uncompromising words can give the wrong impression. “People seem to think that I am depressed, or angry, or worried, but that’s not true,” she said. Having a cause makes her happy. “It was like I got meaning in my life.”

Also from that piece: Thunberg doesn’t live at home; she lives in a safe-house “in a kind of witness-protection program” situation because, one would assume, she gets a lot of threats due of her work.

This new video from Kurzgesagt takes a look at the possible role of nuclear energy in helping to curb the effects of our climate emergency.

Do we need nuclear energy to stop climate change? More and more voices from science, environmental activists and the press have been saying so in recent years — but this comes as a shock to those who are fighting against nuclear energy and the problems that come with it. So who is right? Well — it is complicated.

Rebecca Tuhus-Dubrow wrote about climate change activists who are embracing nuclear energy for the New Yorker back in February.

In the course of years, Hoff grew increasingly comfortable at the plant. She switched roles, working in the control room and then as a procedure writer, and got to know the workforce — mostly older, avuncular men. She began to believe that nuclear power was a safe, potent source of clean energy with numerous advantages over other sources. For instance, nuclear reactors generate huge amounts of energy on a small footprint: Diablo Canyon, which accounts for roughly nine per cent of the electricity produced in California, occupies fewer than six hundred acres. It can generate energy at all hours and, unlike solar and wind power, does not depend on particular weather conditions to operate. Hoff was especially struck by the fact that nuclear-power generation does not emit carbon dioxide or the other air pollutants associated with fossil fuels. Eventually, she began to think that fears of nuclear energy were not just misguided but dangerous. Her job no longer seemed to be in tension with her environmentalist views. Instead, it felt like an expression of her deepest values.

For more reading on the topic, check out Kurzgesagt’s list of source materials used to make their video.

In an opinion piece for Scientific American, Sarah Jaquette Ray argues that our response to the climate emergency must be equitable, or as she puts it: “We can’t fight climate change with more racism.”

One year ago, I published a book called A Field Guide to Climate Anxiety. Since its publication, I have been struck by the fact that those responding to the concept of climate anxiety are overwhelmingly white. Indeed, these climate anxiety circles are even whiter than the environmental circles I’ve been in for decades. Today, a year into the pandemic, after the murder of George Floyd and the protests that followed, and the attack on the U.S. Capitol, I am deeply concerned about the racial implications of climate anxiety. If people of color are more concerned about climate change than white people, why is the interest in climate anxiety so white? Is climate anxiety a form of white fragility or even racial anxiety? Put another way, is climate anxiety just code for white people wishing to hold onto their way of life or get “back to normal,” to the comforts of their privilege?

This is one of those articles where I want to quote the whole thing, so I’ll just do one more paragraph, leave a link to her book, and then just let you read it.

The prospect of an unlivable future has always shaped the emotional terrain for Black and brown people, whether that terrain is racism or climate change. Climate change compounds existing structures of injustice, and those structures exacerbate climate change. Exhaustion, anger, hope-the effects of oppression and resistance are not unique to this climate moment. What is unique is that people who had been insulated from oppression are now waking up to the prospect of their own unlivable future.

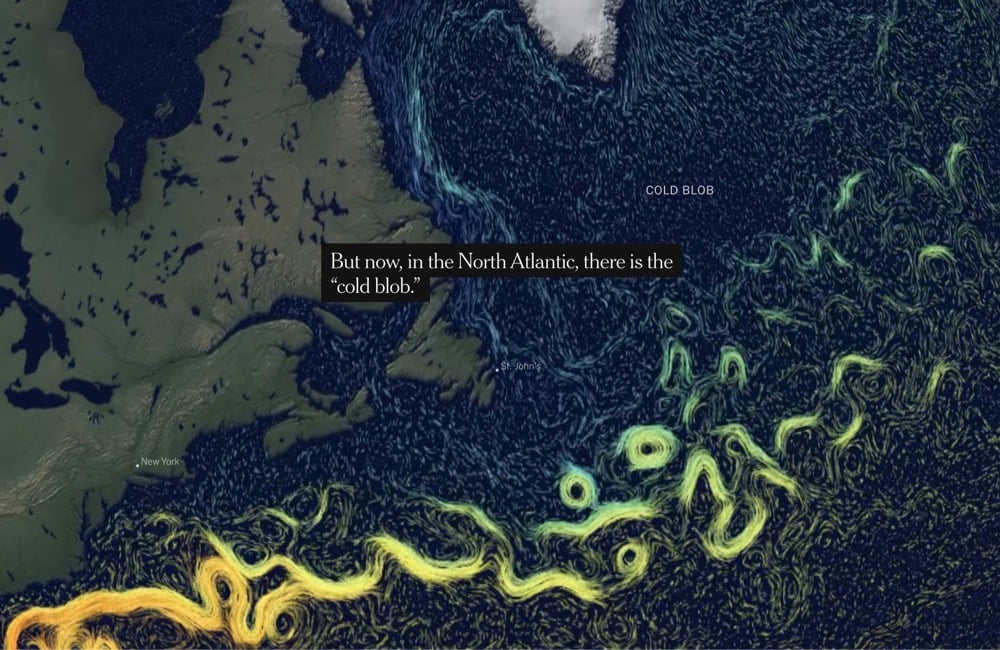

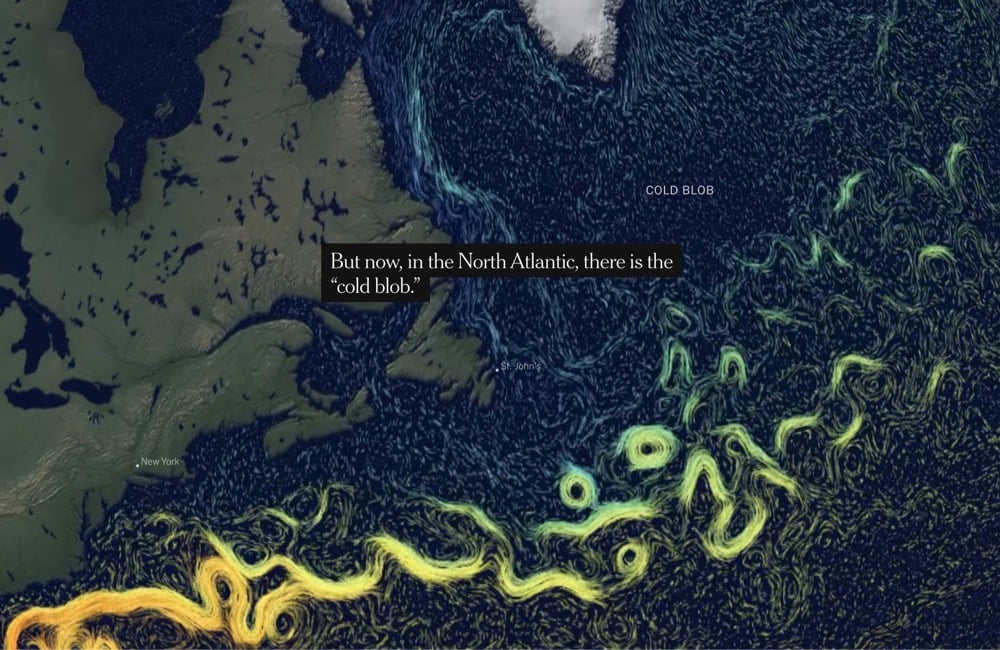

The NY Times has a fantastic interactive piece about a particularly disturbing aspect of the climate crisis: the evidence that a huge Atlantic circulation pattern is weakening and could collapse, leading to “a monstrous change” in temperature, precipitation, and other chaotic effects across the globe.

Now, a spate of studies, including one published last week, suggests this northern portion of the Gulf Stream and the deep ocean currents it’s connected to may be slowing. Pushing the bounds of oceanography, scientists have slung necklace-like sensor arrays across the Atlantic to better understand the complex network of currents that the Gulf Stream belongs to, not only at the surface, but hundreds of feet deep.

“We’re all wishing it’s not true,” Peter de Menocal, a paleoceanographer and president and director of the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, said of the changing ocean currents. “Because if that happens, it’s just a monstrous change.”

The consequences could include faster sea level rise along parts of the Eastern United States and parts of Europe, stronger hurricanes barreling into the Southeastern United States, and perhaps most ominously, reduced rainfall across the Sahel, a semi-arid swath of land running the width of Africa that is already a geopolitical tinderbox.

One of the potential reasons for this weakening is that the quickly melting Greenland ice sheet is dumping massive amounts of cold fresh water into the North Atlantic, disrupting the Gulf Stream. This is “the cold blob”.

The northern arm of the Gulf Stream is but one tentacle of a larger, ocean-spanning tangle of currents called the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation, or AMOC. Scientists have strong evidence from ice and sediment cores that the AMOC has weakened and shut down before in the past 13,000 years. As a result, mean temperatures in parts of Europe may have rapidly dropped to about 15 degrees Celsius below today’s averages, ushering in arctic like conditions. Parts of northern Africa and northern South America became much drier. Rainfall may even have declined as far away as what is now China. And some of these changes may have occurred in a matter of decades, maybe less.

The AMOC is thus a poster child for the idea of climatic “tipping points” — of hard-to-predict thresholds in Earth’s climate system that, once crossed, have rapid, cascading effects far beyond the corner of the globe where they occur. “It’s a switch,” said Dr. de Menocal, and one that can be thrown quickly.

Which brings us to the cold blob. Almost everywhere around the world, average temperatures are rising — except southeast of Greenland where a large patch of the North Atlantic has become colder in recent years.

The title of this post references a “frozen Europe” but because the Earth is a nonlinear system, a weakened AMOC could actually have the opposite effect:

Scientists at the U.K.’s National Oceanography Centre have somewhat counterintuitively linked the cold blob in the North Atlantic with summer heat waves in Europe. In 2015 and 2018, the jet stream, a river of wind that moves from west to east over temperate latitudes in the northern hemisphere, made an unusual detour to the south around the cold blob. The wrinkle in atmospheric flow brought hotter-than-usual air into Europe, they contend, breaking temperature records.

“That was not predicted,” said Joel Hirschi, principal scientist at the centre and senior author of the research. It highlights how current seasonal forecasting models are unable to predict these warm summers. And it underscores the paradox that, far from ushering in a frigid future for, say, Paris, a cooler North Atlantic might actually make France’s summers more like Morocco’s.

(thx, meg)

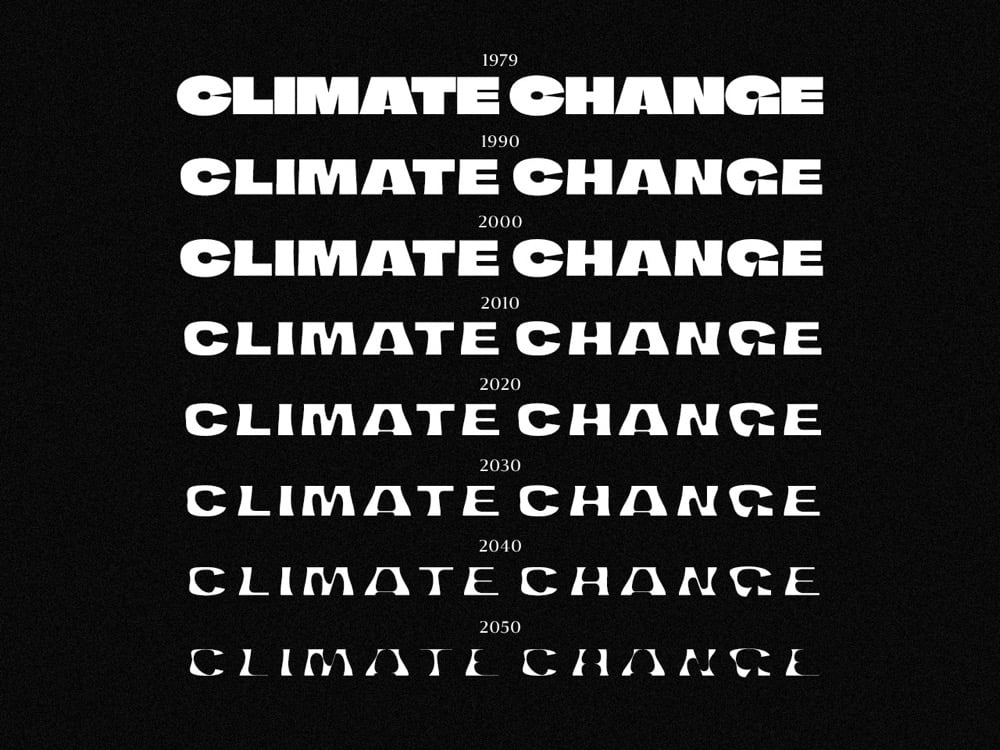

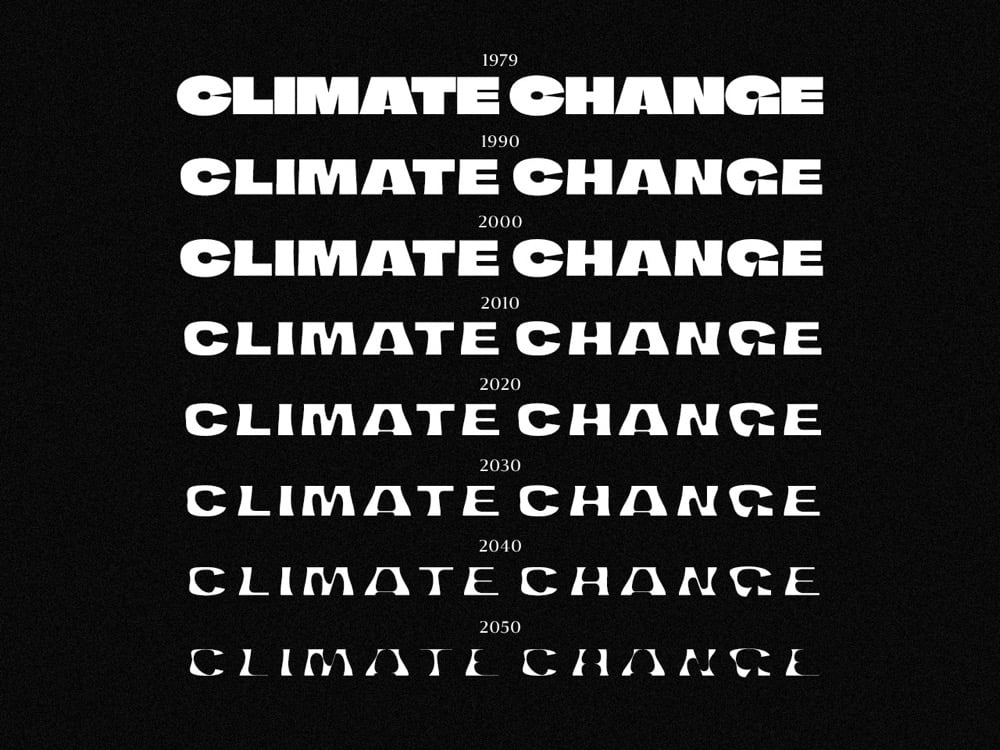

Finnish newspaper Helsingin Sanomat has released a free typeface called Climate Crisis that can help designers and the media visualize the urgency of the climate crisis.

The font is intended to be used by anyone who wishes to visualize the urgency of climate change. Especially the media can use it to enhance its climate-related storytelling through illustrations and dramatizations. Newspaper Helsingin Sanomat is at the moment using the font to draw attention to its climate-related stories.

The typeface has seven weights corresponding to data & projections of the minimum extent of the Arctic sea ice from 1979 to 2050. As you can see in the graphic above, the type gets thinner and thinner as the years pass. (via print)

At the Biden/Harris inauguration on Wednesday, poet Amanda Gorman, dressed in the yellow of the Sun, realigned the planets with her recitation of a poem called The Hill We Climb. In 2018 for The Climate Reality Project, riffing off of the iconic photo of the Earth rising over the surface of the Moon taken by Apollo 8 astronauts, Gorman wrote a poem called Earthrise about the climate emergency and the action we must take to end it. From the text of the poem:

Where despite disparities

We all care to protect this world,

This riddled blue marble, this little true marvel

To muster the verve and the nerve

To see how we can serve

Our planet. You don’t need to be a politician

To make it your mission to conserve, to protect,

To preserve that one and only home

That is ours,

To use your unique power

To give next generations the planet they deserve.

We are demonstrating, creating, advocating

We heed this inconvenient truth, because we need to be anything but lenient

With the future of our youth.

And while this is a training,

in sustaining the future of our planet,

There is no rehearsal. The time is

Now

Now

Now,

Because the reversal of harm,

And protection of a future so universal

Should be anything but controversial.

So, earth, pale blue dot

We will fail you not.

Watch Gorman’s recitation of it above — you might get some goosebumps. (via eric holthaus)

For Gizmodo, Brian Kahn writes about what the 1/6 terrorist action at the Capitol Building means for the climate crisis.

Climate change is chaos by nature. It means more powerful storms, more intense wildfires, more extreme floods and droughts. It is an assault on the weakest among us, and decades of the right-wing mindset of small government have left the country with fewer resources to deal with the fallout. As the summer’s wildfires show, the far-right will be there to try to fill the power void. Those fires occurred in a predominantly white region.

There’s a strong strain of white nationalism and neo-Nazism that ran through Wednesday’s insurrection, and it’s easy to imagine what will happen when flames or storms hit places that are predominantly Black, brown, or Indigenous. In fact, we don’t need to imagine it at all. We’ve seen it in the gunman who showed up at a Walmart to kill immigrants whom he falsely blamed for putting strain on the environment. And we saw it in the white vigilante violence in the vacuum after Hurricane Katrina hit New Orleans. We’ve seen it so frequently, it even has a name: ecofascism.

After Wednesday, the boundaries of permissible violence have now expanded to a distorting degree, at a time of increasing climate instability. White supremacists, neo-Nazis, and other extremists literally took over the halls of power and got away with it. When climate change upends communities with far fewer defenses — communities that hate groups already scapegoat — the results will be catastrophic.

As we’ve seen with the pandemic, fascists will use climate chaos to assert dominance and snatch for power. Others will make vast sums of money — and inequality will continue to grow. Creating confusion with misinformation makes all of that easier to manage for these opportunists.

On his blog, Conor Barnes shared an eclectic list of 100 Tips For A Better Life. I’m less keen on these sorts of lists than I used to be because they’re often written for people who already have pretty good lives and it’s too easy to imagine that a list advocating the opposite of each tip would also lead to a better life. To be fair, Barnes’ list acknowledges the difficulty with generalized advice:

31. The best advice is personal and comes from somebody who knows you well. Take broad-spectrum advice like this as needed, but the best way to get help is to ask honest friends who love you.

That said, here are some of the list items that resonated with me in some way.

3. Things you use for a significant fraction of your life (bed: 1/3rd, office-chair: 1/4th) are worth investing in.

I recently upgraded my mattress from a cheap memory foam one I’d been using for almost 7 years to a hybrid mattress that was probably 3X the cost but is so comfortable and better for my back.

13. When googling a recipe, precede it with ‘best’. You’ll find better recipes.

I’ve been doing this over the past year with mixed results. Google has become a terrible way to find good recipes, even with this trick. My version of this is googling “kenji {name of dish}” — works great.

27. Discipline is superior to motivation. The former can be trained, the latter is fleeting. You won’t be able to accomplish great things if you’re only relying on motivation.

My motivation is sometimes very low when it comes to working on this here website. But my discipline is off the charts, so it gets done 99 days out of 100, even in a pandemic. (I am still unclear whether this is healthy for me or not…)

46. Things that aren’t your fault can still be your responsibility.

48. Keep your identity small. “I’m not the kind of person who does things like that” is not an explanation, it’s a trap. It prevents nerds from working out and men from dancing.

Oh, this used to be me: “I’m this sort of person.” Turns out, not so much.

56. Sometimes unsolvable questions like “what is my purpose?” and “why should I exist?” lose their force upon lifestyle fixes. In other words, seeing friends regularly and getting enough sleep can go a long way to solving existentialism.

75. Don’t complain about your partner to coworkers or online. The benefits are negligible and the cost is destroying a bit of your soul.

Interpreting “partner” broadly here, I completely agree with this one. If they are truly a partner (romantic, business, parenting), complaining is counterproductive. Instead, talk to others about how those relationships can be repaired, strengthened, or, if necessary, brought to an appropriate end.

88. Remember that many people suffer invisibly, and some of the worst suffering is shame. Not everybody can make their pain legible.

91. Human mood and well-being are heavily influenced by simple things: Exercise, good sleep, light, being in nature. It’s cheap to experiment with these.

This is good advice, but some of these things actually aren’t “cheap” for some people.

100. Bad things happen dramatically (a pandemic). Good things happen gradually (malaria deaths dropping annually) and don’t feel like ‘news’. Endeavour to keep track of the good things to avoid an inaccurate and dismal view of the world.

Oof, this ended on a flat note. Many bad things seem to happen dramatically because we don’t notice the results of small bad decisions accumulating over time that lead to sudden outcomes. Like Hemingway said about how bankruptcy happens: gradually, then suddenly. Lung cancer doesn’t happen suddenly; it’s the 40 years of cigarettes. California’s wildfires are the inevitable result of 250 years of climate change & poor forestry management techniques. Miami and other coastal cities are being slowly claimed by the ocean — they will reach breaking points in the near future. Even the results of something like earthquakes or hurricanes can be traced to insufficient investment in safety measures, policy, etc.

The pandemic seemed to come out of nowhere, but experts in epidemiology & infectious diseases had been warning about a pandemic just like this one for years and even decades. The erosion of public trust in government, the politicization of healthcare, the deemphasis of public health, and the Republican death cult (which is its own slow-developing disaster now reaching a crisis) controlling key aspects of federal, state, and local government made the pandemic impossible to contain in America. (This is true of most acute crises in the United States. Where you find people suffering, there are probably decades or even centuries of public policy to blame.)

Bad news happens slowly and unnoticed all the time. You don’t have to look any further for evidence of this than how numb we are to the fact that thousands of Americans are dying every single day from a disease that we know how to control. So, endeavour to keep track of the bad things to avoid an inaccurate and unrealistically optimistic view of the world — it helps in making a list of injustices to pay attention to and work against.

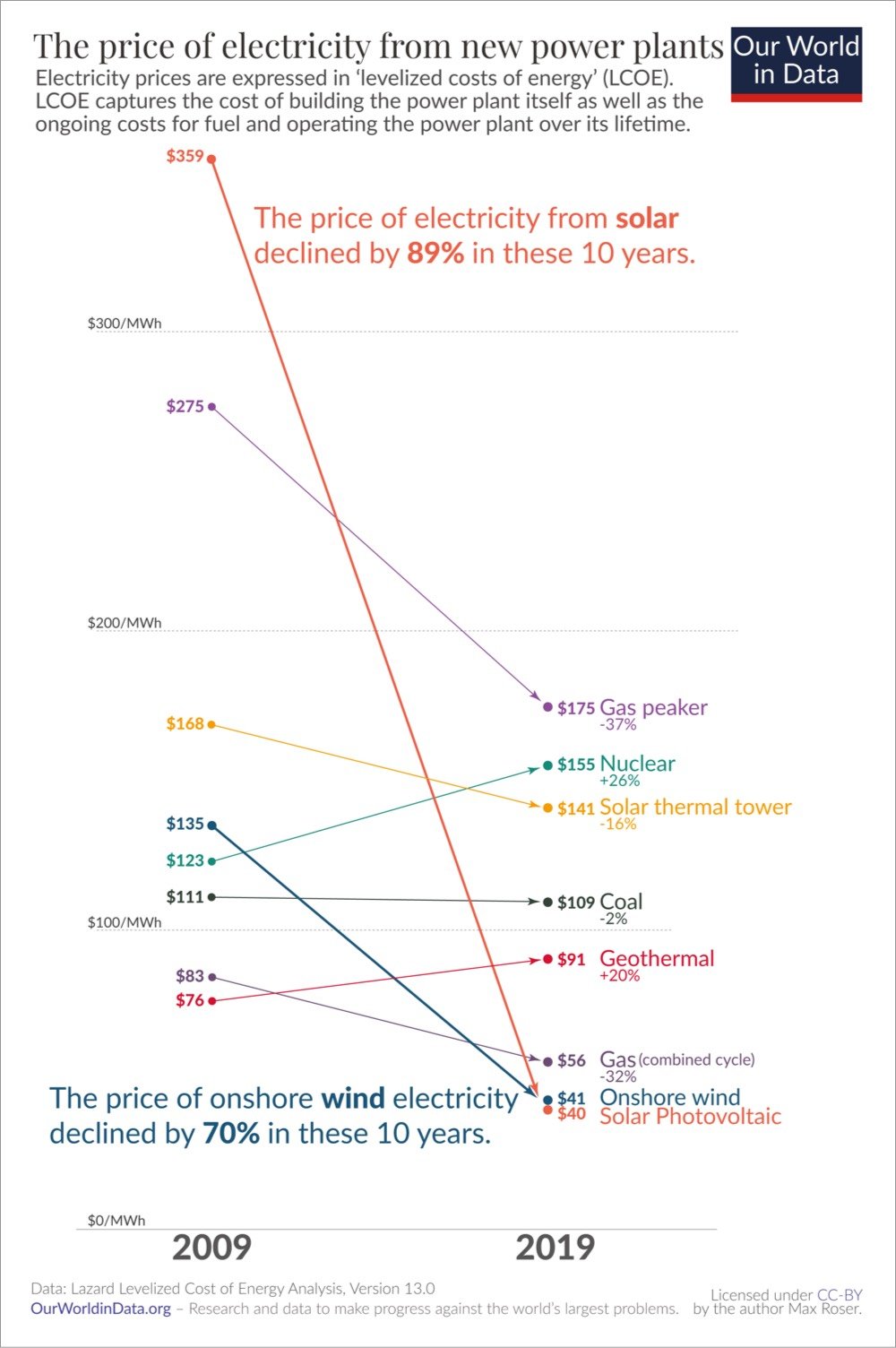

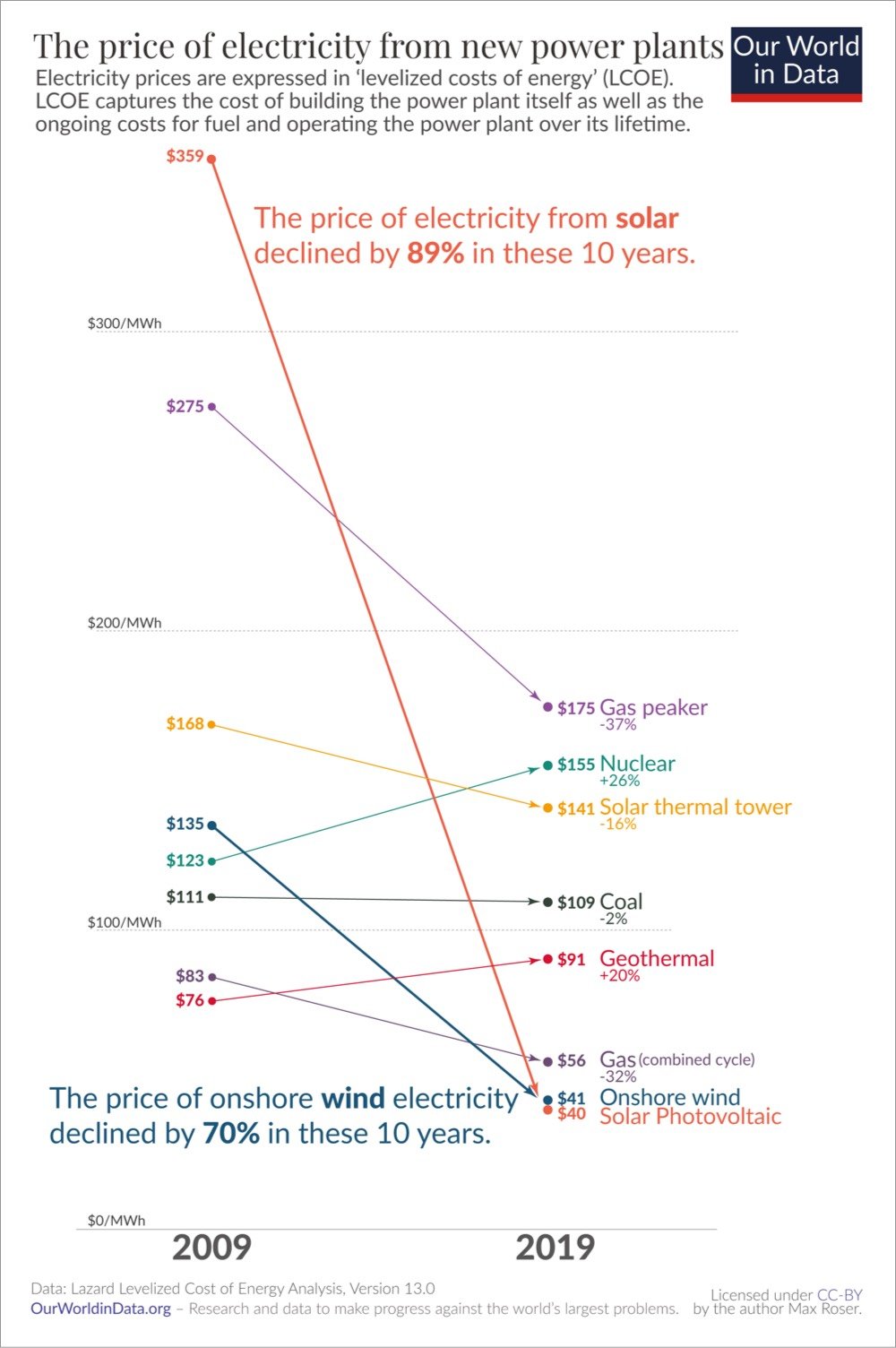

Check out this graph from Our World in Data of the price of electricity from new power plants. In 2009, solar was the most expensive energy source and in 2019 it’s the cheapest.

Electricity from utility-scale solar photovoltaics cost $359 per MWh in 2009. Within just one decade the price declined by 89% and the relative price flipped: the electricity price that you need to charge to break even with the new average coal plant is now much higher than what you can offer your customers when you build a wind or solar plant.

It’s hard to overstate what a rare achievement these rapid price changes represent. Imagine if some other good had fallen in price as rapidly as renewable electricity: Imagine you’d found a great place to live back in 2009 and at the time you thought it’d be worth paying $3590 in rent for it. If housing had then seen the price decline that we’ve seen for solar it would have meant that by 2019 you’d pay just $400 for the same place.

The rest of the page is worth a read as well. One reason why the cost of solar is falling so quickly is that the technology is following a similar exponential curve to computer chips, which provide more speed and power every year for less money, an observation called Wright’s Law:

If you want to know what the future looks like one of the most useful questions to ask is which technologies follow Wright’s Law and which do not.

Most technologies obviously do not follow Wright’s Law — the prices of bicycles, fridges, or coal power plants do not decline exponentially as we produce more of them. But those which do follow Wright’s Law — like computers, solar PV, and batteries — are the ones to look out for. They might initially only be found in very niche applications, but a few decades later they are everywhere.

If you are unaware that technology follows Wright’s Law you can get your predictions very wrong. At the dawn of the computer age in 1943 IBM president Thomas Watson famously said “I think there is a world market for maybe five computers.” At the price point of computers at the time that was perhaps perfectly true, but what he didn’t foresee was how rapidly the price of computers would fall. From its initial niche when there was perhaps truly only demand for five computers they expanded to more and more applications and the virtuous cycle meant that the price of computers declined further and further. The exponential progress of computers expanded their use from a tiny niche to the defining technology of our time.

Solar modules are on the same trajectory, as we’ve seen before. At the price of solar modules in the 1950s it would have sounded quite reasonable to say, “I think there is a world market for maybe five solar modules.” But as a prediction for the future this statement too would have been ridiculously wrong.

Earlier this month, Prince William (British royal) & David Attenborough (British royalty) announced The Earthshot Prize. Inspired by the moonshot effort of the 1960s, the initiative will award five £1 million (~$1.3 million) prizes each year over the next 10 years for projects that provide global solutions to pressing environmental problems in five different categories: fixing the climate, cleaning the air, protecting & restoring nature, reviving the oceans, and building a waste-free world.

The Earthshot Prize is centred around five ‘Earthshots’ — simple but ambitious goals for our planet which if achieved by 2030 will improve life for us all, for generations to come. Each Earthshot is underpinned by scientifically agreed targets including the UN Sustainable Development Goals and other internationally recognised measures to help repair our planet.

Together, they form a unique set of challenges rooted in science, which aim to generate new ways of thinking, as well as new technologies, systems, policies and solutions. By bringing these five critical issues together, The Earthshot Prize recognises the interconnectivity between environmental challenges and the urgent need to tackle them together.

(via moss & fog)

Newer posts

Older posts

Socials & More