The Moral Calculus of COVID-19

COVID-19 has required all of us to scrutinize our actions and sacrifice our desires and even our obligations in order to keep ourselves and those around us safe. I want to examine two cases where reasonable, well-informed, and influential people make entirely different choices based on largely similar evidence.

You may have heard that MSNBC host Rachel Maddow has been quarantining at home following close contact with a person who had tested positive for COVID-19. You may have also heard that last night, Maddow returned to her show (still filming from home) to reveal that this person was her partner of 20+ years, artist/photographer Susan Mikula. Mikula is recovering, but at at least one point, the couple genuinely feared for her life. Maddow herself is still testing negative; with Mikula in much less danger and Maddow nearing the end of quarantine, they felt it was time to open the curtain on their experience.

If you haven’t seen it already, I’d like you to watch the video of Maddow describing her experience of living with a loved one who is suffering from COVID-19, whom you have to care for but cannot touch without grave risk to yourself, and then to others. (It is about Mikula’s own experience, but it’s really much more about Maddow’s experience, for good reason.)

Here’s a quick excerpt, if you want a textual preview (via Vulture):

“Just believe me: Whatever you have calculated into your life as acceptable risk, as inevitable risk, something that you’re willing to go through in terms of this virus because statistically, hey probably, it will be fine for you and your loved ones, I’m just here to tell you to recalibrate that,” [Maddow] warned. “Frankly, the country needs you to recalibrate that because broadly speaking, there’s no room for you in the hospital right now.”

She cites hospitals being overwhelmed with a “50 percent” increase in patients “in two weeks.” While it may be easy to risk your own life, the virus doesn’t let you make the choice. “What you need to know is whoever’s the most important person in your life, whoever you most love and most care for and most cherish in the world, that’s the person who you may lose and who you may spend weeks up all night freaking out about and calling doctors all over the place and over and over again all night long, trying to figure out how to keep that person breathing and out of the hospital,” she said. “Whatever you’re doing, however you’ve calibrated risk in your life, don’t get this thing.”

Another moment worth noting in the video is shortly after she begins. Maddow is interrupted by a recurring beeping noise in a room off-camera. She has to attend to it herself, in the middle of a live television show, because there’s no one else at home who can do it. She takes off her microphone and earpiece, then has to put it back on. After already revealing at the beginning of the show that she’s not wearing makeup—she doesn’t know how to apply it herself, and no one can help her—it’s a nice peek behind the scenes.

I don’t know if everyone always understands how much work it takes it is to perform for live television: how many accessories you need, how much support is required. People don’t see what you have to look like, sound like, or act like; they don’t see the almost cyborg contraption you have to become in order to make a successful television appearance. Being good at television is a specific skill. It’s as different from writing, reporting, or public speaking as football, baseball, and basketball are from playing polo. It doesn’t matter if you have your words on a teleprompter (although that does help): you still have to deliver them, in time, no backsies, and look and sound good while you’re doing it.

The disruption of the show also happens in the middle of a charming metaphor Maddow uses to describe her relationship:

The way that I think about it is not that she is the sun and I’m a planet that orbits her—that would give too much credit to the other planets. I think of it more as a pitiful thing: that she is the planet and I am a satellite, and I’m up there sort of beep-beep-beeping at her and blinking my lights and just trying to make her happy.

Compare this to Farhad Manjoo’s essay in The New York Times today, “I Traced My COVID-19 Bubble and It’s Enormous.” Manjoo starts with a classic dilemma: he knows it’s unsafe in general to travel for Thanksgiving, but he wonders if it might be safer for his family, given the size of their social circle and the precautions they’ve taken. He’d like to find out more, to replace his general intuitions, which pull him in both directions, with something more concrete. This is a time-honored journalistic premise (a rhetorical trope, really) for answering a question many people might have.

In researching his close contacts, and their own exposure to other people, Manjoo quickly has cold water thrown on the notion that his bubble is in any way contained to the degree he’d imagined it to be. (This part of the story is well-illustrated: I’ll give you the text excerpts, but it’s worth clicking through and scrolling through yourself.)

I thought my bubble was pretty small, but it turned out to be far larger than I’d guessed.

My only close contacts each week are my wife and kids.

My kids, on the other hand, are in a learning pod with seven other children and my daughter attends a weekly gymnastics class.

I emailed the parents of my kids’ friends and classmates, as well as their teachers, and asked how large each family’s bubble was.

Already, my network was up to almost 40 people.

Turns out a few of the families in our learning pod have children in day care or preschool.

And one’s classmate’s mother is a doctor who comes into contact with about 10 patients each week.

Once I had counted everyone, I realized that visiting my parents for Thanksgiving would be like asking them to sit down to dinner with more than 100 people.

He isn’t actually done counting yet: from himself, he’s only gone to three degrees of separation. But presumably, the point in the headline is made. The author’s bubble is enormous, and presumably the reader’s is, too.

Then a curious thing happens. Manjoo decides that what he’s learned doesn’t matter. He thinks his family and his contacts are special after all. “All of my indirect contacts are taking the virus seriously—none of them spun conspiracy theories about the pandemic, or suggested it was no big deal or told me to bug off and mind my own business.” (This is a very low threshold for “taking the virus seriously.”) And he would really like to take his wife and children to see his parents. An epidemiologist gives him some cover, saying his desire to see their parents is understandable, and it’s all a matter of assessing and evaluating risk.

So, he changes his mind again. He makes a few concessions (drive, not fly; an outdoor meal rather than an indoor one; staying off-site rather than sleeping over). And he’s going to travel five hours each way with his wife and children and their 100+ direct and indirect contacts to celebrate Thanksgiving with his parents.

This is contrarianism on a scale not usually seen in a newspaper article. (They’re usually too short to take this many turns.) It is one thing to counter received wisdom by posing a counterfactual. It is another to spend hours of reporting, gathering facts, calling in experts, putting everything on the record, and then deciding that none of that matters.

On Twitter, I called it “the full Gladwell”; only Malcolm Gladwell at The New Yorker can consistently pull this hairpin twist off and stick the landing, even if he frequently violates good sense and plain facts to do it.

It’s important, though, that this is not just a rhetorical trick. These are the real lives of real people, both in the story itself, and radiating out to its readers and their contacts in a global newspaper, the United States’ paper of record. And the reasoning and evidence that are considered but discarded gives the illusion that this is a choice motivated not by setting reason aside, but considering all options and maximizing one’s expected utility.

Not to “both sides” this, but I’m gonna “both sides” this: in some sense, both Maddow and Manjoo are putting their thumb on the scales, in opposite directions. For Maddow, the experience of almost losing the love of her life makes it so that she would take no willing risk that might endanger her or anyone else. (She acknowledges that a certain amount of unavoidable, unwilling risk remains.)

Manjoo is different. He acknowledges that he has no such experience. He is less concerned with the possible loss of his parents’ lives than the loss of their presence in his life and in their childrens’ lives. He sees the willing assumption of risk as an open moral question, and something that can be calculated and appropriately mitigated.

Maddow has constructed a universe where she is a tiny satellite orbiting a much larger planet, whose continued health and existence is the central focus of her concern. Manjoo has drawn a map with himself at its center, where anyone beyond the reach of his telephone falls off the edges.

Maddow is also explicitly pleading with her viewers to learn what they can from her experience, and adjust their behavior accordingly. Manjoo is performing his calculus only for himself; he implicitly presents himself as a representative example (while also claiming he and his circle are extraordinarily conscientious and effective), but each reader can draw their own conclusions and make their own decision.

At this point the balancing dominoes tip over. Maddow’s position, her argument, and her example are clearly more moral and more persuasive than Manjoo’s. Manjoo’s essay is worth reading, but the conclusion is untenable. It doesn’t do the work needed to arrive there or persuade anyone else to do the same. And at a time when many people are spinning conspiracies about the pandemic, or claiming that it’s no big deal, and in turn influencing others—when we haven’t even yet considered the virus’s impact on the uncounted number of people, from medical staff and many other essential workers to prisoners and the impoverished, who do not simply get to choose how to spend their holiday—it’s irresponsible.

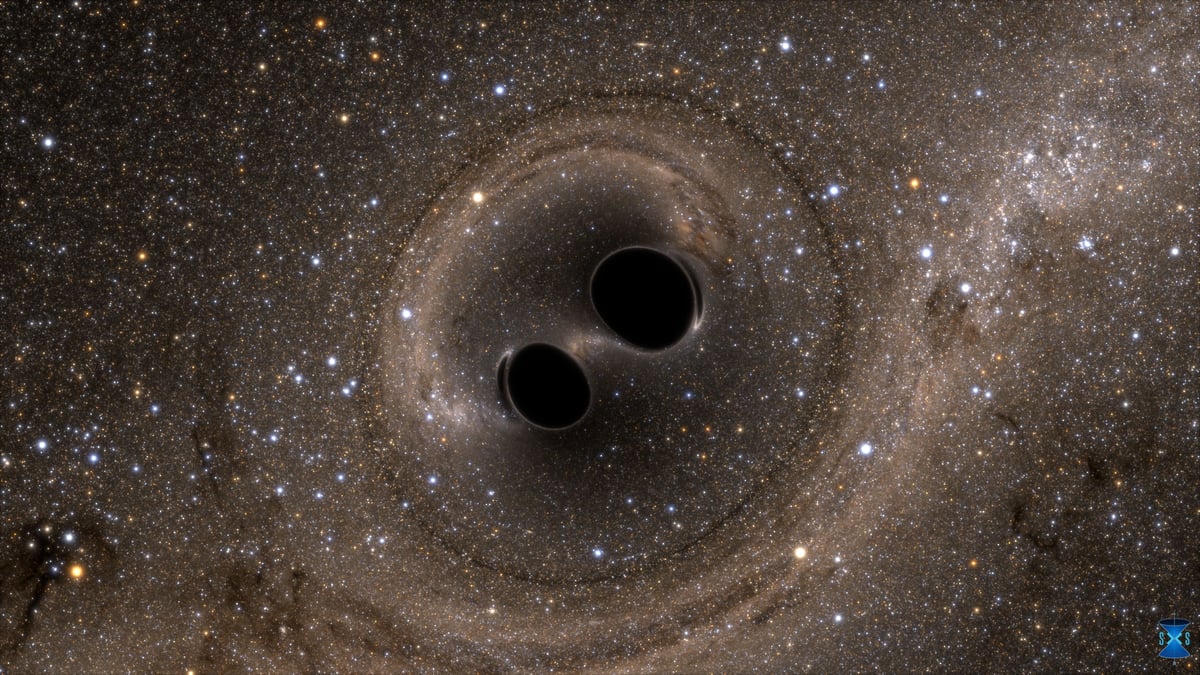

The larger moral tragedy is that because our leaders have failed, and too often actually worked to damage the infrastructure, expertise, and goodwill accumulated over generations, we have no consistent, authoritative guidance on what we should and should not do. We do not know who to trust. We have no money, no help, and no plan but to wait. We have no sense of what rules our friends and neighbors, colleagues and workers, are following when they’re not in our sight; we don’t even know what practices they would even admit to embracing. We have no money; we have no help. We are left on our own, adrift in deep space, scribbling maps and adding sums on the back of a napkin. We are all in this together, yet we are completely alone.

Stay Connected