kottke.org posts about science

Plants eat light, grow almost everywhere on Earth, and make up 99% of the planet’s biomass. But do what extent do plants think? Or feel? Michael Pollan tackles the question of plant intelligence in a thought-provoking article for the New Yorker (sadly behind their paywall).

Indeed, many of the most impressive capabilities of plants can be traced to their unique existential predicament as beings rooted to the ground and therefore unable to pick up and move when they need something or when conditions turn unfavorable. The “sessile life style” as plant biologists term it, calls for an extensive and nuanced understanding of one’s immediate environment, since the plant has to find everything it needs, and has to defend itself, while remaining fixed in place. A highly developed sensory apparatus is required to locate food and identify threats. Plants have evolved between fifteen and twenty different senses, including analogues of our five: smell and taste (they sense and respond to chemicals in the air or on their bodies); sight (they react differently to various wavelengths of light as well as to shadow); touch (a vine or root “knows” when it encounters a solid object); and, it has been discovered, sound.

In a recent experiment, Heidi Appel, a chemical ecologist at the University of Missouri, found that, when she played a recording of a caterpillar chomping a leaf for a plant that hadn’t been touched, the sound primed the the plant’s genetic machinery to produce defense chemicals. Another experiment, dome in Mancuso’s lab and not yet published, found that plant roots would seek out a buried pipe through which water was flowing even if the exterior of the pipe was dry, which suggested that plants somehow “hear” the sound of flowing water.

One of the researchers featured in the article, Stefano Mancuso, has a TED talk available in which he outlines his case for plant intelligence:

The article also discusses if plants have feelings. If so, should we feel bad that our wifi routers might kill plants?

Update: Mancuso and Alessandra Viola have collaborated on a new book about the intelligence of plants, Brilliant Green: The Surprising History and Science of Plant Intelligence.

There’s art on the Moon, a small sculpture called Fallen Astronaut. Artist Paul van Hoeydonck made it. Commander David Scott of Apollo 15 placed it on the Moon in 1971. Instead of a triumph, the whole thing fell into scandal and was forgotten.

In reality, van Hoeydonck’s lunar sculpture, called Fallen Astronaut, inspired not celebration but scandal. Within three years, Waddell’s gallery had gone bankrupt. Scott was hounded by a congressional investigation and left NASA on shaky terms. Van Hoeydonck, accused of profiteering from the public space program, retreated to a modest career in his native Belgium. Now both in their 80s, Scott and van Hoeydonck still see themselves unfairly maligned in blogs and Wikipedia pages-to the extent that Fallen Astronaut is remembered at all.

And yet, the spirit of Fallen Astronaut is more relevant today than ever. Google is promoting a $30 million prize for private adventurers to send robots to the moon in the next few years; companies such as SpaceX and Virgin Galactic are creating a new for-profit infrastructure of human spaceflight; and David Scott is grooming Brown University undergrads to become the next generation of cosmic adventurers.

Governments come and go, public sentiment waxes and wanes, but the dream of reaching to the stars lives on. Fallen Astronaut does, too, hanging eternally 238,000 miles above our heads. Here, for the first time, we tell the full, tangled tale behind one of the smallest yet most extraordinary achievements of the Space Age.

In a fly-by of Earth on its way to Jupiter, NASA’s Juno probe took a short movie of the Moon orbiting the Earth. It’s the first time the Moon’s orbit has been captured on film.

(via @DavidGrann)

Using a large piece of spandex (representing spacetime) and some balls and marbles (representing masses), a high school science teacher explains how gravity works.

The bits about how the planets all orbit in the same direction and the demo of the Earth/Moon orbit are really neat. And you can stop watching around the 7-minute mark…the demos end around then.

Update: Here’s another video of a similar system with some slightly different demos.

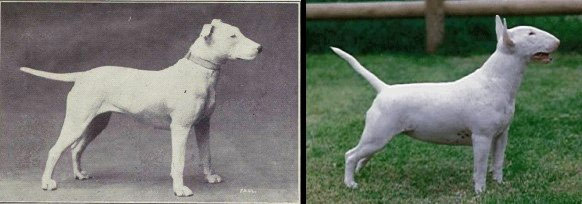

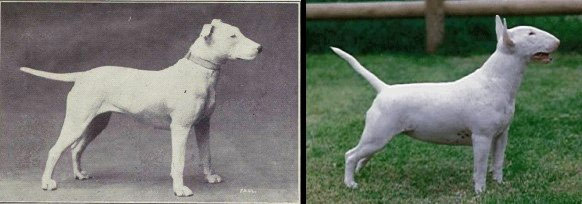

From a blog about the science of dogs, a comparison of photos of purebred dogs from 1915 to those of today. You can see how much the dogs have changed in just under 100 years, in some cases for the worse. For instance, the difference in the Bull Terrier (aka the Spuds MacKenzie dog) is marked and a bit disturbing:

Pure breeding has also introduced medical problems for some breeds.

The English bulldog has come to symbolize all that is wrong with the dog fancy and not without good reason; they suffer from almost every possible disease. A 2004 survey by the Kennel Club found that they die at the median age of 6.25 years (n=180). There really is no such thing as a healthy bulldog. The bulldog’s monstrous proportions makes them virtually incapable of mating or birthing without medical intervention.

(via @mulegirl)

Your body clock alarm is just as accurate as the one on your phone: your body naturally takes note of what time you want to wake up and wakes you up.

There’s evidence you can will yourself to wake on time, too. Sleep scientists at Germany’s University of Lubeck asked 15 volunteers to sleep in their lab for three nights. One night, the group was told they’d be woken at 6 a.m., while on other nights the group was told they’d be woken at 9 a.m..

But the researchers lied-they woke the volunteers at 6 a.m anyway. And the results were startling. The days when sleepers were told they’d wake up early, their stress hormones increased at 4:30 a.m., as if they were anticipating an early morning. When the sleepers were told they’d wake up at 9 a.m., their stress hormones didn’t increase — and they woke up groggier. “Our bodies, in other words, note the time we hope to begin our day and gradually prepare us for consciousness,” writes Jeff Howe at Psychology Today.

(via digg)

From Wikipedia, a list of products and technologies that have been developed with the help of NASA, including memory foam, Dustbusters, and powdered lubricants.

For more than 50 years, the NASA Innovative Partnerships Program has connected NASA resources to private industry, referring to the commercial products as spin-offs. Well-known products that NASA claims as spin-offs include memory foam (originally named temper foam), freeze-dried food, firefighting equipment, emergency “space blankets”, Dustbusters, cochlear implants, and now Speedo’s LZR Racer swimsuits. NASA claims that there are over 1650 other spin-offs in the fields of computer technology, environment and agriculture, health and medicine, public safety, transportation, recreation, and industrial productivity.

NASA did not, however, invent Teflon or Velcro. (via @tangentialism)

Hans Bethe was a giant in the field of nuclear physics. He rubbed shoulders with Einstein, Bohr, and Pauli, was head of the Theoretical Division of the US atomic bomb project, and was awarded a Nobel Prize. In 1999, at the age of 93, Bethe gave a series of three lectures to the residents of his retirement community near Cornell University, where he had taught since 1935. Video of the lectures is available on the Cornell website.

In the first lecture, Bethe covers the development of the “old quantum theory”, covering the work of Max Planck and Niels Bohr. In the second and third lectures, he relates how modern quantum mechanics was developed, with a healthy amount of personal recollection along the way:

Professor Bethe offers personal anecdotes about many of the famous names commonly associated with quantum physics, including Bohr, Heisenberg, Born, Pauli, de Broglie, Schrödinger, and Dirac.

Without a doubt, this is the most high-power presentation ever made at a retirement home. (via @stevenstrogatz)

Google and NASA recently bought a D-Wave quantum computer. But according to a piece by Sophie Bushwick published on the Physics Buzz Blog, there isn’t scientific consensus on whether the computer is actually using quantum effects to calculate.

In theory, quantum computers can perform calculations far faster than their classical counterparts to solve incredibly complex problems. They do this by storing information in quantum bits, or qubits.

At any given moment, each of a classical computer’s bits can only be in an “on” or an “off” state. They exist inside conventional electronic circuits, which follow the 19th-century rules of classical physics. A qubit, on the other hand, can be created with an electron, or inside a superconducting loop. Obeying the counterintuitive logic of quantum mechanics, a qubit can act as if it’s “on” and “off” simultaneously. It can also become tightly linked to the state of its fellow qubits, a situation called entanglement. These are two of the unusual properties that enable quantum computers to test multiple solutions at the same time.

But in practice, a physical quantum computer is incredibly difficult to run. Entanglement is delicate, and very easily disrupted by outside influences. Add more qubits to increase the device’s calculating power, and it becomes more difficult to maintain entanglement.

(via fine structure)

Not to get all Malcolm Gladwell here, but it’s counterintuitive that hot water freezes faster than cold water. The phenomenon is called the Mpemba effect and until recently, no one could explain how it works. A group of researchers in Singapore think they’ve cracked the puzzle.

Now Xi and co say hydrogen bonds also explain the Mpemba effect. Their key idea is that hydrogen bonds bring water molecules into close contact and when this happens the natural repulsion between the molecules causes the covalent O-H bonds to stretch and store energy.

But as the liquid warms up, it forces the hydrogen bonds to stretch and the water molecules sit further apart. This allows the covalent molecules to shrink again and give up their energy. The important point is that this process in which the covalent bonds give up energy is equivalent to cooling.

In fact, the effect is additional to the conventional process of cooling. So warm water ought to cool faster than cold water, they say. And that’s exactly what is observed in the Mpemba effect.

(via ★djacobs)

This video dicusses three simple ways to travel through time (all of which you can do right now at home) and three not-so-simple time travel methods.

For more on time-travel, here are some works by physicist and time-lord Sean Carroll:

Rules for time-travellers - http://blogs.discovermagazine.com/cos…

Learn more about time and time-machines in his book From Eternity to Here - http://preposterousuniverse.com/etern…

Visualizations of the spinning universe - http://iopscience.iop.org/1367-2630/1…

An engaging talk on the Paradoxes of Time Travel - https://vimeo.com/11917849

(via digg)

NASA’s Solar Dynamics Observatory is getting some really amazing shots of the Sun, including this 200,000 mile-long solar eruption that left a huge canyon on the surface of the Sun:

Different wavelengths help capture different aspect of events in the corona. The red images shown in the movie help highlight plasma at temperatures of 90,000° F and are good for observing filaments as they form and erupt. The yellow images, showing temperatures at 1,000,000° F, are useful for observing material coursing along the sun’s magnetic field lines, seen in the movie as an arcade of loops across the area of the eruption. The browner images at the beginning of the movie show material at temperatures of 1,800,000° F, and it is here where the canyon of fire imagery is most obvious.

The level of detail shown is incredible. (via @DavidGrann)

In an interview accompanying a Frontline episode on drug-resistant bacteria, an associate director for the CDC, Dr. Arjun Srinivasan, says that “we’re in the post-antibiotic era”.

The more you use an antibiotic, the more you expose a bacteria to an antibiotic, the greater the likelihood that resistance to that antibiotic is going to develop. So the more antibiotics we put into people, we put into the environment, we put into livestock, the more opportunities we create for these bacteria to become resistant. …We also know that we’ve greatly overused antibiotics and in overusing these antibiotics, we have set ourselves up for the scenario that we find ourselves in now, where we’re running out of antibiotics.

We are quickly running out of therapies to treat some of these infections that previously had been eminently treatable. There are bacteria that we encounter, particularly in health-care settings, that are resistant to nearly all — or, in some cases, all — the antibiotics that we have available to us, and we are thus entering an era that people have talked about for a long time.

For a long time, there have been newspaper stories and covers of magazines that talked about “The end of antibiotics, question mark?” Well, now I would say you can change the title to “The end of antibiotics, period.”

We’re here. We’re in the post-antibiotic era. There are patients for whom we have no therapy, and we are literally in a position of having a patient in a bed who has an infection, something that five years ago even we could have treated, but now we can’t.

You know how when you first hear a joke it’s the funniest thing ever and then you hear it a second time and it’s less funny and then a third, fourth, and fifth times and it just keeps getting less and less funny until you’re not laughing at all and it actually becomes annoying? That’s how antibiotics work across the entire human population. And if Dr. Srinivasan is correct, we’re transitioning into the not laughing stage and the annoying stage where lots of people start dying can’t be far behind (unless we get some new jokes/treatments).

Yesterday, Mark Sample tweeted about disasters, low-points, and chronic trauma:

“Low point” is the term for when the worst part of a disaster has come to pass. Our disasters increasingly have no low point.

After the low point of a disaster is reached, things begin to get better. When there is no clear low point, society endures chronic trauma.

Disasters with no clear low point: global warming, mass extinction, colony collapse disorder, ocean acidification, Fukushima.

To which I would add: drug-resistant infectious diseases. (via digg)

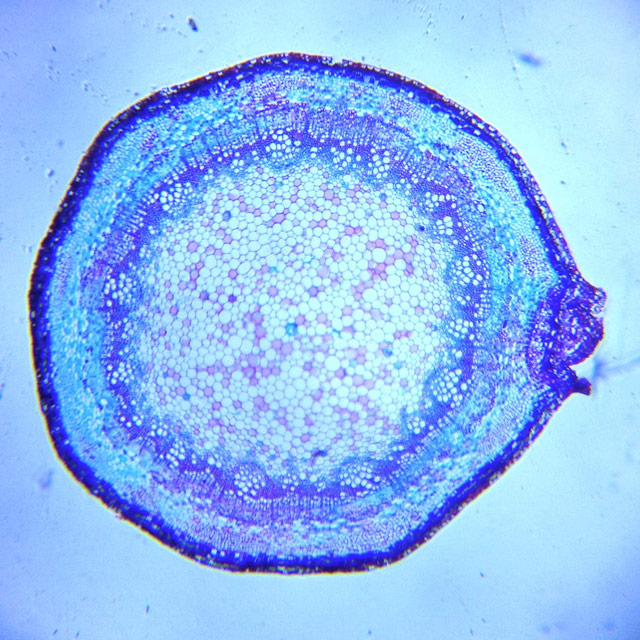

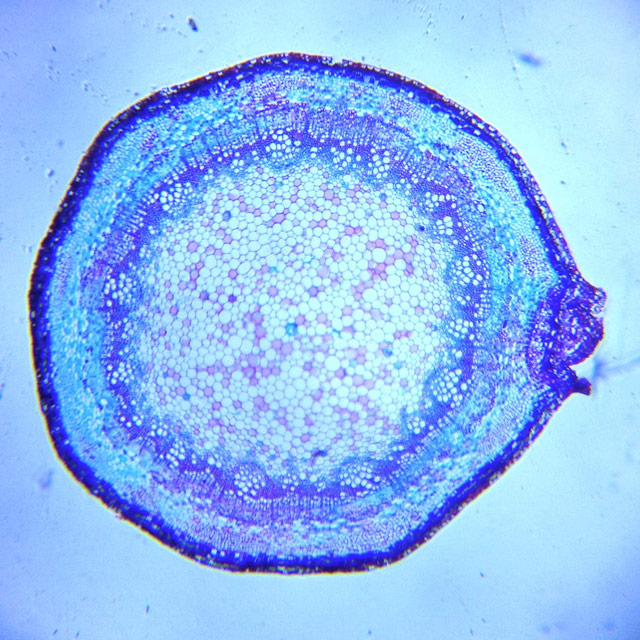

With $10 and a little elbow grease, you can turn your iPhone into a really nice digital microscope capable of 175x magnification, allowing you to take photos of plant cells:

Here’s how you do it:

(via ★interesting)

For the New York Review of Books, theoretical physicist and Nobel laureate Steven Weinberg gives us an update on what we know and don’t know about physics.

It turns out that particles already known to us are not enough to account for the mass of the hot matter in which the sound waves must have propagated. Fully five sixths of the matter of the universe would have to be some kind of “dark matter,” which does not emit or absorb light. The existence of this much dark matter in the present universe had already been inferred from the fact that clusters of galaxies hold together gravitationally, despite the high random speeds of the galaxies in the clusters. So this is a great puzzle: What is the dark matter? Theories abound, and attempts are underway to catch ambient dark matter particles or remnants of their annihilation in detectors on Earth or to create dark matter in accelerators. But so far dark matter has not been found, and no one knows what it is.

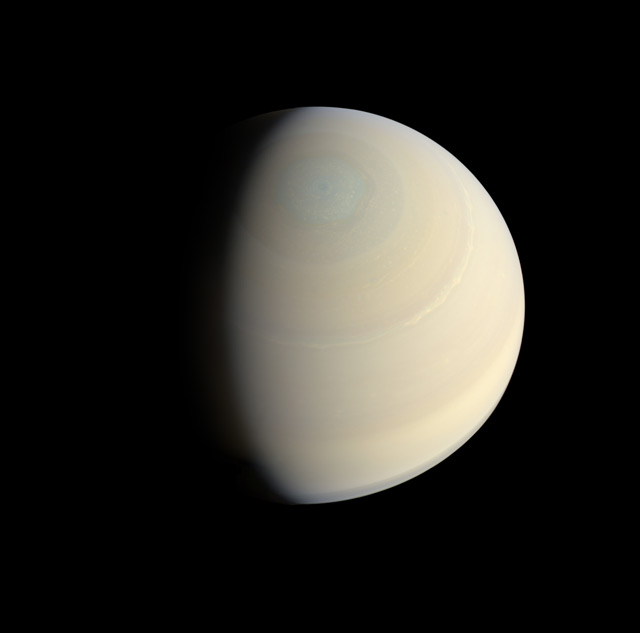

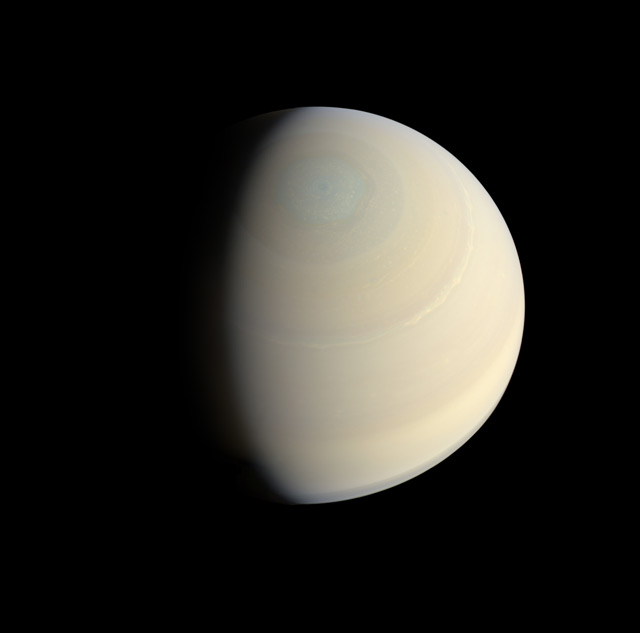

Over at The Planetary Society, Emily Lakdawalla highlighted an image taken by the Cassini spacecraft of Saturn separate from its rings.

This enormous mosaic showing the flattened globe of Saturn floating amongst the complete disk of its rings must surely be counted among the great images of the Cassini mission. From Earth, we never see Saturn separate from its rings. Here, we can see the whole thing, a gas giant like Jupiter, separated at last from the rings that encircle it.

Taking this idea one step further, I removed the rings completely, along with the “ringlight” lighting up the night hemisphere, creating a more-or-less pure look of what Saturn would look like without its rings.

Larger version is available on Mlkshk.

Google’s got themselves a quantum computer (they’re sharing it with NASA) and they made a little video about it:

I’m sure that Hartmut is a smart guy and all, but he’s got a promising career as an Arnold Schwarzenegger impersonator hanging out there if the whole Google thing doesn’t work out.

A promising debut by Sarah Pavis of a science program called Square 1, an attempt at a Connections-like show for the modern day. In the first episode, she explores how phone touchscreens work.

In addition to being an occasional guest editor around these parts, Sarah is a mechanical engineer, so she knows her science.

What if there were a new class of wonder drugs for children that prevented some of the worst diseases in history with very limited side effects…would you take them? Some people don’t “trust” that wacky “science” though.

What’s so confounding is that many of the parents requesting exemptions for their children cite specious, disproven fears — such as that the vaccine could cause autism — many of which were based on a fraudulent, retracted study or fringe research published in non-peer-reviewed journals. And the rest of the country hasn’t been as successful as Massachusetts in containing measles infections. Earlier this year, an intentionally unvaccinated 17-year-old from Brooklyn, New York, was infected with measles while on a trip to the United Kingdom. Because he lived in a community with a large number of other deliberately unvaccinated children, the virus quickly spread. By the time the outbreak was contained, 58 people had been infected — making it the largest outbreak in the country in more than 15 years. Nationwide, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported 159 total cases between January and August, which puts 2013 on track to record the most domestic measles infections since the disease was declared eliminated from the United States in 2000.

Declared eliminated! [Hair-tearing-out noise]

Scientists have discovered the source of a massive 13th century volcanic eruption: a volcano called Samalas on Indonesia’s Lombok Island. The blast was eight times as powerful as Krakatoa.

Though the eruption was equatorial, its impact was felt and noted around the world. “The climate was disturbed for at least two years after the eruption,” Lavigne said. Evidence of this was found in studies of tree rings that revealed abnormal growth rates, climate models, and historical records from as far afield as Europe.”

Medieval chronicles, for example, describe the summer of 1258 as unseasonably cold, with poor harvests and incessant rains that triggered destructive floods — a “year without a summer.” The winter immediately following the eruption was warmer in western Europe, however, as would be expected from high-sulfur eruptions in the tropics. The team cites historical records from Arras (northern France) that speak of a winter so mild “that frost barely lasted for more than two days,” and even in January 1258 “violets could be observed, and strawberries and apple trees were in blossom.”

Note that at a volume of 40 km3 of debris, Samalas doesn’t even come close to being on the list of the 40 most explosive volcanic eruptions in history, most of which happened millions of years ago. (via digg)

Light (aka electromagnetic radiation) is responsible for most of what we know about the universe. By measuring photons of various frequencies in different ways — “the careful collection of ancient light” — we’ve painted a picture of our endless living space. But light isn’t perfect. It can bend, scatter, and be blocked. Changes in gravity are more difficult to detect, but new instruments may allow scientists to construct a different map of the universe and its beginnings.

LIGO works by shooting laser beams down two perpendicular arms and measuring the difference in length between them-a strategy known as laser interferometry. If a sufficiently large gravitational wave comes by, it will change the relative length of the arms, pushing and pulling them back and forth. In essence, LIGO is a celestial earpiece, a giant microphone that listens for the faint symphony of the hidden cosmos.

Like many exotic physical phenomena, gravitational waves originated as theoretical concepts, the products of equations, not sensory experience. Albert Einstein was the first to realize that his general theory of relativity predicted the existence of gravitational waves. He understood that some objects are so massive and so fast moving that they wrench the fabric of spacetime itself, sending tiny swells across it.

How tiny? So tiny that Einstein thought they would never be observed. But in 1974 two astronomers, Russell Hulse and Joseph Taylor, inferred their existence with an ingenious experiment, a close study of an astronomical object called a binary pulsar [see “Gravitational Waves from an Orbiting Pulsar,” by J. M. Weisberg et al.; Scientific American, October 1981]. Pulsars are the spinning, flashing cores of long-exploded stars. They spin and flash with astonishing regularity, a quality that endears them to astronomers, who use them as cosmic clocks. In a binary pulsar system, a pulsar and another object (in this case, an ultradense neutron star) orbit each other. Hulse and Taylor realized that if Einstein had relativity right, the spiraling pair would produce gravitational waves that would drain orbital energy from the system, tightening the orbit and speeding it up. The two astronomers plotted out the pulsar’s probable path and then watched it for years to see if the tightening orbit showed up in the data. The tightening not only showed up, it matched Hulse and Taylor’s predictions perfectly, falling so cleanly on the graph and vindicating Einstein so utterly that in 1993 the two were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics.

Friday morning is as good a time as any to revisit what I consider one of the quintessential Kottke.org post(s), The case of the plane and conveyor belt. Essentially, will an airplane take off on a treadmill. Prompted by a question on The Straight Dope, the post, now over 7 years old, has everything you need for a Kottke.org post: airplanes, physics, a waffle, and careful consideration of the facts. The question was addressed again a few days later to definitively and succinctly put the argument to rest.

Now that I’ve closed the comments on the question of the airplane and the conveyor belt, I’m still getting emails calling me an idiot for thinking that the plane will take off. Having believed that after first hearing the question and formulating several reasons reinforcing my belief, I can sympathize with that POV, but that doesn’t change the fact that I was initially wrong and that if you believe the plane won’t take off, you’re wrong too.

A 2008 liveblog of an episode of Mythbusters, further cemented the following notion:

For what it’s worth commenters almost everywhere continue to disagree. For more opinions, see here, here, here, here.

In the 1980s, Charles Ehret developed an antidote to jet lag called The Argonne Anti-Jet-Lag-Diet.

After experimenting on protozoa, rats, and his eight children, Ehret recommended that the international traveler, in the several days before his flight, alternate days of feasting with days of very light eating. Come the flight, the traveler would nibble sparsely until eating a big breakfast at about 7:30 a.m. in his new time zone — no matter that it was still 1:30 a.m. in the old time zone or that the airline wasn’t serving breakfast until 10:00 a.m. His reward would be little or no jet lag.

The diet was adopted by US government agencies and other groups as well as Ronald Reagan, but it difficult to stick to. Recently, researchers in Boston have devised a simpler anti-jet lag remedy:

The international traveler, they counsel, can avoid jet lag by simply not eating for twelve to sixteen hours before breakfast time in the new time zone-at which point, as in Ehret’s diet, he should break his fast. Since most of us go twelve to sixteen hours between dinner and breakfast anyway, the abstention is a small hardship.

According to the Harvard team, the fast works because our bodies have, in addition to our circadian clock, a second clock that might be thought of as a food clock or, perhaps better, a master clock. When food is scarce, this master clock suspends the circadian clock and commands the body to sleep much less than normally. Only after the body starts eating again does the master clock switch the circadian clock back on.

Totally trying this the next time I have to travel, although the Advil PM/melatonin combination my doctor suggested worked really well for me on my trip to New Zealand. (via @genmon)

I had no idea that’s how rubber bands worked. Once again, Feynman takes something that seems pretty simple and makes it both simpler and vividly complex.

(via @stevenstrogatz)

A Texas man was getting drunk without drinking alcohol and his doctors think they figured out why: brewer’s yeast in his in gut was brewing beer and making the man intoxicated.

The patient had an infection with Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Cordell says. So when he ate or drank a bunch of starch — a bagel, pasta or even a soda — the yeast fermented the sugars into ethanol, and he would get drunk. Essentially, he was brewing beer in his own gut. Cordell and McCarthy reported the case of “auto-brewery syndrome” a few months ago in the International Journal of Clinical Medicine.

Some clever entrepreneur will undoubtedly turn this syndrome into a product…the market opportunity for a pill that allows you to get drunk on spaghetti *and* be the owner/operator of your own microbrewery is too large to ignore. (via ★interesting)

For the first time, researchers have put together all the climate data they have (from ice cores, coral, sediment drilling) into one chart that shows the “global temperature reconstruction for the last 11,000 years”:

The climate curve looks like a “hump”. At the beginning of the Holocene - after the end of the last Ice Age - global temperature increased, and subsequently it decreased again by 0.7 ° C over the past 5000 years. The well-known transition from the relatively warm Medieval into the “little ice age” turns out to be part of a much longer-term cooling, which ended abruptly with the rapid warming of the 20th Century. Within a hundred years, the cooling of the previous 5000 years was undone. (One result of this is, for example, that the famous iceman ‘Ötzi’, who disappeared under ice 5000 years ago, reappeared in 1991.)

What on Earth could have caused that spike over the past 250 years? A real head-scratcher, that. But also, what would have happened had the Industrial Revolution and the corresponding anthropogenic climate change been delayed a couple hundred years? The Earth might have been in the midst of a new ice age, Europe might have been too cold to support industry, and things may not have gotten going at all. Who’s gonna write the screenplay for this movie? (via @CharlesCMann)

Volume 1 of The Feynman Lectures on Physics is now available in HTML form. What a fantastic resource.

Nearly fifty years have passed since Richard Feynman taught the introductory physics course at Caltech that gave rise to these three volumes, The Feynman Lectures on Physics. In those fifty years our understanding of the physical world has changed greatly, but The Feynman Lectures on Physics has endured. Feynman’s lectures are as powerful today as when first published, thanks to Feynman’s unique physics insights and pedagogy. They have been studied worldwide by novices and mature physicists alike; they have been translated into at least a dozen languages with more than 1.5 millions copies printed in the English language alone. Perhaps no other set of physics books has had such wide impact, for so long.

The apples that you buy at the market are all from the same species of plant, Malus domestica. Within that species, there are 7,500 different varieties (or cultivars) of apples. The list of apple cultivars includes Red Delicious, Macoun, Honeycrisp, Granny Smith, and the like. They look and taste different but are all recognizable as apples.

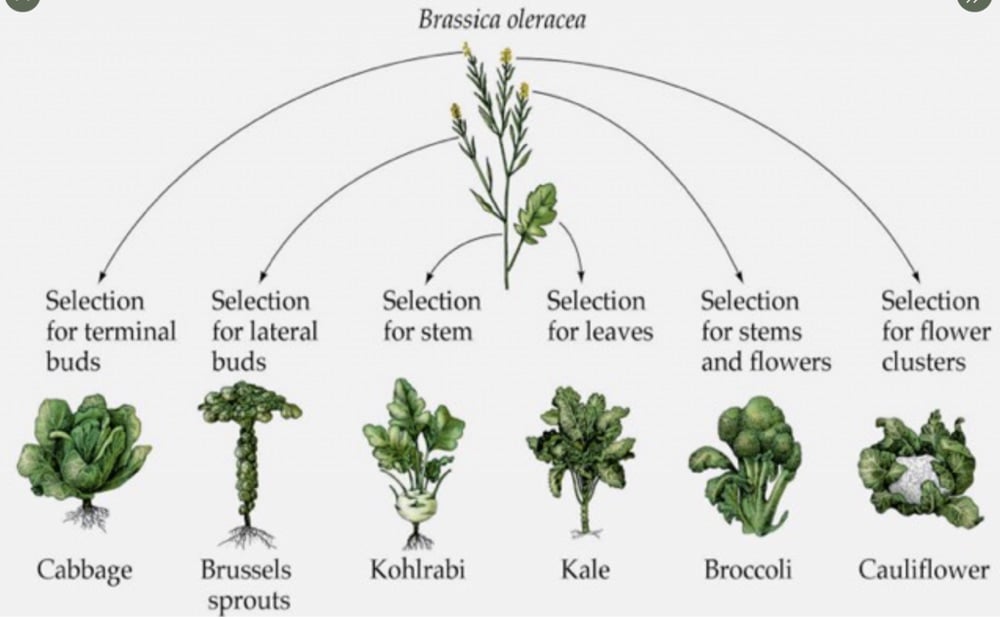

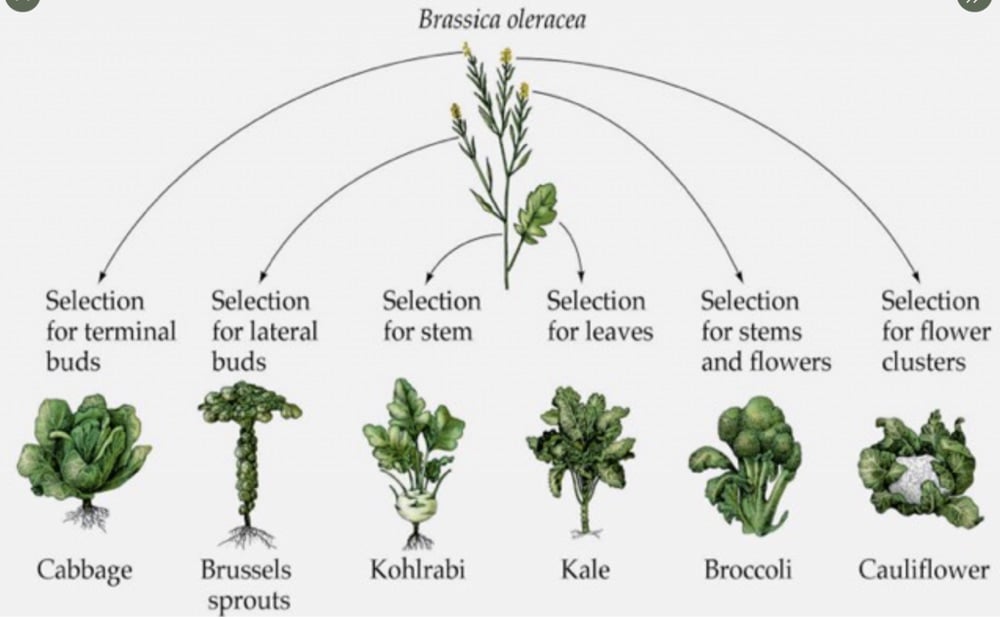

Brassica oleracea is a species of plant that, like the apple, has a number of different cultivars. But these cultivars differ widely from each other: cabbage, kale, broccoli, brussels sprouts, kohlrabi, collard greens, and cauliflower. Nutty that all those vegetables come from the same species of plant. (via @ajsheets)

Old people, like those who live to be older than 30, didn’t exist in great numbers until about 30,000 years ago. Why is that? Anthropologist Rachel Caspari speculates that around that time, enough people were living long enough to function as a shared cultural hard drive for humans, a living memory bank for skills, histories, family trees, etc. that helped human groups survive longer.

Caspari says it wasn’t a biological change that allowed people to start living reliably to their 30s and beyond. (When she looked at other populations of Neanderthals and Homo sapiens that lived in the same place and time, the two different species had similar proportions of old people, suggesting the change was not genetic.) Instead, it was culture. Something about how people were living made it possible to survive into old age, maybe the way they found or stored food or built shelters, who knows. That’s all lost-pretty much all we have of them is teeth-but once humans found a way to keep old people around, everything changed.

Old people are repositories of information, Caspari says. They know about the natural world, how to handle rare disasters, how to perform complicated skills, who is related to whom, where the food and caves and enemies are. They maintain and build intricate social networks. A lot of skills that allowed humans to take over the world take a lot of time and training to master, and they wouldn’t have been perfected or passed along without old people. “They can be great teachers,” Caspari says, “and they allow for more complex societies.” Old people made humans human.

What’s so special about age 30? That’s when you’re old enough to be a grandparent. Studies of modern hunter-gatherers and historical records suggest that when older people help take care of their grandchildren, the grandchildren are more likely to survive. The evolutionary advantages of living long enough to help raise our children’s children may be what made it biologically plausible for us to live to once unthinkably old ages today.

I took a Greek and Roman literature class in college. Among the texts we studied was Lucretius’ On The Nature of Things. Shamefully, about the only thing I remembered from it was that the poem was an early articulation of the concept of atoms (see also Democritus). Impressive, chatting about atoms in 50 BCE. But reading Stephen Greenblatt’s The Swerve has reminded me what an impressive and prescient document it is, quite apart from its beauty as a poem. In chapter eight of his book, Greenblatt summarizes the main points of Lucretius’ poem:

Everything is made of invisible particles.

The elementary particles of matter — “the seeds of things” — are eternal.

The elementary particles are infinite in number but limited in shape and size.

All particles are in motion in an infinite void.

The universe has no creator or designer.

Everything comes into being as a result of a swerve.

[Ok, the swerve deserves a bit of explanation. Here’s Greenblatt:

If all the individual particles, in their infinite numbers, fell through the void in straight lines, pulled down by their own weight like raindrops, nothing would ever exist. But the particles do no move lockstep in a preordained single direction. Instead, “at absolutely unpredictable time and places they deflect slightly from their straight course, to a degree that could be described as no more than a shift of movement.” The position of the elementary particles is thus indeterminate.

I can’t help but think of quantum mechanics here. Anyway, back to the list.]

The swerve is the source of free will.

Nature ceaselessly experiments.

The universe was not created for or about humans.

Humans are not unique.

Human society began not in a Golden Age of tranquility and plenty, but in a primitive battle for survival.

The soul dies.

There is no afterlife.

Death is nothing to us.

All organized religions are superstitious delusions.

Religions are invariably cruel.

There are no angels, demons, or ghosts.

The highest goal of human life is the enhancement of pleasure and the reduction of pain.

The greatest obstacle to pleasure is not pain; it is delusion.

Understanding the nature of things generates deep wonder.

The seeds of atomic theory, quantum mechanics, evolution, agnosticism, atheism…they’re all right there, in a poem written by a man who died more than 2000 years ago.

Newer posts

Older posts

Stay Connected