kottke.org posts about books

GQ has an excerpt of Rosecrans Baldwin’s new book about the eighteen months he and his wife spent in Paris.

Bruno sat under a machine shaped like a palm tree that sucked up smoke. He lit a cigarette, unpopped a shirt button nonchalantly, ordered Sancerre, and began talking over my head. After fifteen minutes, I understood that he’d worked on the infant-nutrition project for eleven months, ever since he’d joined the agency. They’d gone through four copywriters in the same amount of time; I was number five.

Bruno said, Reservoir Dogs, did I know this film?

“Bien sur,” I said, adding, “Mr. Pink?”

“Okay, good,” Bruno said in English. “Then, Mr. Pink… do not be this. Do not be saying in the office, ‘Fuck, fuck, fuck.’”

Evidently Bruno had overheard me swearing. He wanted me to know that cursing wasn’t cool in Parisian office culture. It seemed to weigh on Bruno, speaking English like that, correcting my behavior. As though envisioning trials to come.

The book is called Paris, I Love You But You’re Bringing Me Down and is due out soooon.

Adam Mansbach will blurb your novel, but it’s gonna cost you. Here’s part of his price list:

You live in one of the following neighborhoods: Brooklyn Heights, Park Slope, Boerum Hill, Carroll Gardens, Williamsburg. (+$150)

You claim to be friends with a friend of mine, but that friend of mine hates you. (+$100)

The word after the gerund in your two-word title is a proper noun masquerading as a regular noun, i.e. “Losing Ground,” a novel about a man named Peter Ground. (+$250)

Your novel is a retelling of another novel from the perspective of a minor character, a piece of furniture, or a magical being who did not appear in the original. (+$275)

I literally LOL’d (LLOL?) at the last line. (via the blurb-worthy @tadfriend)

Out today: Mike Monteiro’s Design is a Job. The book is an important reminder that how effective you are as a designer depends on many things aside from what you can do in Photoshop or InDesign. You need to build a stable environment for yourself (and your employees) to do your best work: you need to get clients, know how to talk to them, set up a stable and sustainable business, collaborate with others, etc. etc. For a taste of what the book has to offer, A List Apart has an excerpt of the second chapter, Getting Clients.

The biggest lie in this book would be if I told you I don’t worry about where the next client is coming from. I could tell you that once you build up enough of a portfolio, or garner enough experience, or achieve a certain level of notoriety in the industry, this won’t be a concern anymore. I could tell you I sleep soundly, not bolting out of bed at 4 a.m. to run laps around the local high school track. I could tell you that I never worry about enough presents under the tree. I could tell you these things, but I’d be lying. And I don’t want to lie to you. Getting clients is the most petrifying and scary thing I can think of in the world. I’d rather wrestle lady Bengal tigers in heat with meat strapped to my genitals than look for new clients.

If putting in the work to get the kind of work you want to do sounds too daunting, then close this book right now. Walk away. Rethink your life choices and take up a less stressful craft, like cleaning out cobra pits. Do it. No one will think less of you. Cover yourself in sackcloth and pray to your god for penance.

Go!

Kurt Vonnegut is just the bee’s knees, isn’t he? Here’s a letter he wrote in 1973 to the head of the school board at Drake High School in North Dakota after the school burned all of its copies of Slaughterhouse-Five in the school’s furnace.

If you were to bother to read my books, to behave as educated persons would, you would learn that they are not sexy, and do not argue in favor of wildness of any kind. They beg that people be kinder and more responsible than they often are. It is true that some of the characters speak coarsely. That is because people speak coarsely in real life. Especially soldiers and hardworking men speak coarsely, and even our most sheltered children know that. And we all know, too, that those words really don’t damage children much. They didn’t damage us when we were young. It was evil deeds and lying that hurt us.

A book containing David Foster Wallace’s previously uncollected nonfiction is due out in November.

Beloved for his epic agony, brilliantly discerning eye, and hilarious and constantly self-questioning tone, David Foster Wallace was heralded by both critics and fans as the voice of a generation. BOTH FLESH AND NOT gathers 15 essays never published in book form, including “Federer Both Flesh and Not,” considered by many to be his nonfiction masterpiece; “The (As it Were) Seminal Importance of Terminator 2,” which deftly dissects James Cameron’s blockbuster; and “Fictional Futures and the Conspicuously Young,” an examination of television’s effect on a new generation of writers.

There are also several books about Wallace and his writings coming out over the next few months.

In a 1935 piece for Esquire magazine entitled Remembering Shooting-Flying: A Key West Letter, Ernest Hemingway listed seventeen books that were among his favorites. They were so dear to him that he would rather read any of them for the first time again than have a yearly income of a million dollars. (That’s about $16.5 million/year in today’s dollars.) Here’s the actual passage from the article:

When you have been lucky in your life you find that just about the time the best of the books run out (and I would rather read again for the first time Anna Karenina, Far Away and Long Ago, Buddenbrooks, Wuthering Heights, Madame Bovary, War and Peace, A Sportsman’s Sketches, The Brothers Karamozov, Hail and Farewell, Huckleberry Finn, Winesburg, Ohio, La Reine Margot, La Maison Tellier, Le Rouge et le Noire, La Chartreuse de Parme, Dubliners, Yeats’s Autobiographies and a few others than have an assured income of a million dollars a year) you have a lot of damned fine things that you can remember. Then when the time is over in which you have done the things that you can now remember, and while you are doing other things, you find you can read the books again, and, always, there are a few, a very few, good new ones. Last year there was La Condition Humaine by Andre Malraux. It was translated, I do not know how well, as Man’s Fate, and sometimes it is as good as Stendhal and that is something no prose writer has been in France for over fifty years.

But this is supposed to be about shooting, not about books, although some of the best shooting I remember was in Tolstoi and I have often wondered how the snipe fly in Russia now and whether shooting pheasants is counter-revolutionary. When you have loved three things all your life, from the earliest you can remember; to fish, to shoot and, later, to read; and when, all your life, the necessity to write has been your master, you learn to remember and, when you think back, you remember more fishing and shooting and reading than anything else and that is a pleasure.

That creep can roll, man. See also Hemingway kicks a can. (via lists of note)

The Tournament of Books, The Morning News’ annual fiction competition, has begun. If you like books and the NCAA basketball tournament, this is pretty much your thing.

From Project Gutenberg, Francis Grose’s Dictionary in the Vulgar Tongue was published in 1811 and gives the reader a full account of the slang, swears, and insults used at the time.

FLOGGING CULLY. A debilitated lecher, commonly an old one.

COLD PIG. To give cold pig is a punishment inflicted on sluggards who lie too long in bed: it consists in pulling off all the bed clothes from them, and throwing cold water upon them.

TWIDDLE-DIDDLES. Testicles.

TWIDDLE POOP. An effeminate looking fellow.

ROUND ROBIN. A mode of signing remonstrances practised by sailors on board the king’s ships, wherein their names are written in a circle, so that it cannot be discovered who first signed it, or was, in other words, the ringleader.

A modern copy is available on Amazon.

Martin Amis, one of the greatest living British novelists, published a guide to video games in 1982 called Invasion of the Space Invaders: An Addict’s Guide to Battle Tactics, Big Scores and the Best Machines. It has an introduction by Steven Spielberg and Amis has barely acknowledged its existence since its publication.

It’s a deeply strange artifact: an A4-sized, full color glossy affair, abundantly illustrated with captioned photographs, screen shots, and lavish illustrations of exploding space ships and lunar landscapes. It boasts a perfunctory introduction by Steven Spielberg (“read this book and learn from young Martin’s horrific odyssey round the world’s arcades before you too become a video-junkie”), complete with full-page portrait of the Hollywood Boy Wonder leaning awkwardly against an arcade machine like some sort of geeky, high-waisted Fonz. We’re not even into the text proper, and already its cup runneth over with 100-proof WTF.

That’s the subtitle of a book released in 2010 called The Last Leaf by Stuart Lutz. In the book are dozens of interviews with “last survivors or final eyewitness of historically important events”, including the last living pitcher to give up a home run to Babe Ruth in 1927, the last man alive to work with Thomas Edison, and the last American WWI soldier.

When we read about famous historical events, we may wonder about the firsthand experiences of the people directly involved. What insights could be gained if we could talk to someone who remembered the Civil War, or the battle to win the vote for women, or Thomas Edison’s struggles to create the first electric light bulb? Amazingly, many of these experiences are still preserved in living memory by the final survivors of important, world-changing events. In this unique oral history book, author and historic document specialist Stuart Lutz records the stories told to him personally by people who witnessed many of history’s most famous events.

See also human wormholes and the Great Span.

Adapted from her upcoming book Bringing Up Bébé: One American Mother Discovers the Wisdom of French Parenting, Pamela Druckerman shares why French parents are superior in this WSJ article.

The French, I found, seem to have a whole different framework for raising kids. When I asked French parents how they disciplined their children, it took them a few beats just to understand what I meant. “Ah, you mean how do we educate them?” they asked. “Discipline,” I soon realized, is a narrow, seldom-used notion that deals with punishment. Whereas “educating” (which has nothing to do with school) is something they imagined themselves to be doing all the time.

One of the keys to this education is the simple act of learning how to wait. It is why the French babies I meet mostly sleep through the night from two or three months old. Their parents don’t pick them up the second they start crying, allowing the babies to learn how to fall back asleep. It is also why French toddlers will sit happily at a restaurant. Rather than snacking all day like American children, they mostly have to wait until mealtime to eat. (French kids consistently have three meals a day and one snack around 4 p.m.)

We have a French pediatrician who advised us to do almost exactly what is in this article and we’ve had pretty good success with it. It’s not all roses (kids are kids after all) and a lot of work, especially for the first couple of years, because you have to be consistent and steady and firm (but also flexible) and I know I haven’t always done a great job, but the dividends have been totally worth it so far.

Did you know that the Charlotte’s Web audiobook is read by E.B. White himself? He died in 1985 and must have recorded it before then. My wife and son listened to it on a long car trip this weekend and was declared “soooo good”.

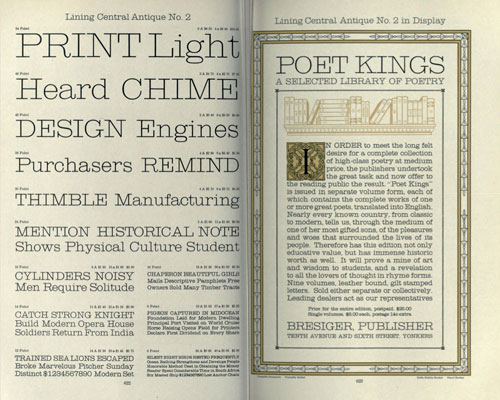

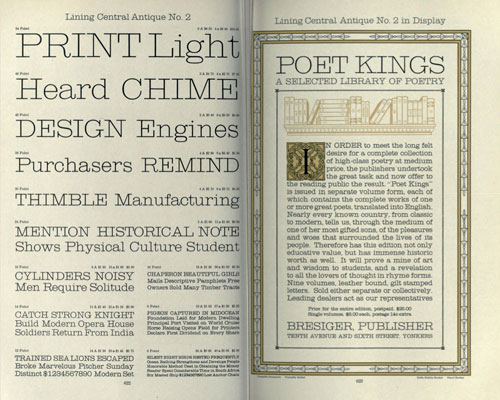

The Internet Archive is hosting a copy of the American Specimen Book of Type Styles put out by the American Type Founders Company in 1912. It’s a 1300-page book listing hundreds of typefaces and their possible use cases.

There’s also a 1910 copy of what is basically the German version of the ATF book. Look at these swirls! (via @h_fj)

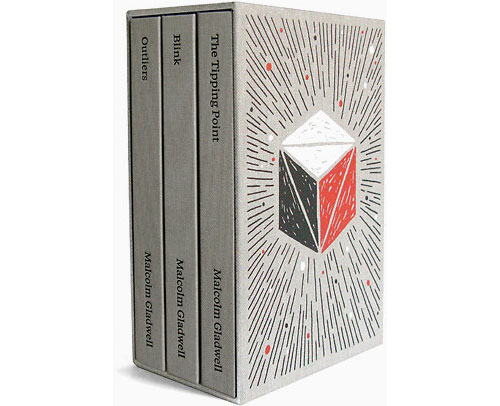

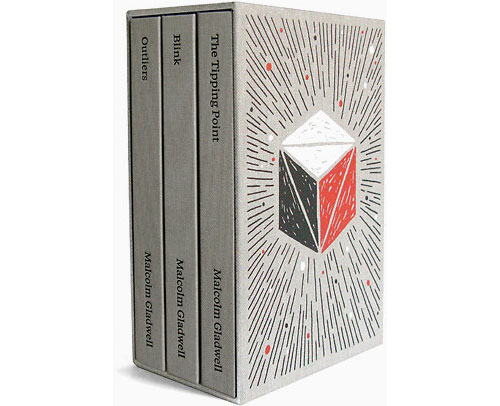

Paul Sahre and Brian Rea designed a 3-book boxed set for Malcolm Gladwell’s “intellectual adventure stories”.

“During our initial meeting with Malcolm, he referred to the three books as ‘intellectual adventure stories,’” Sahre tells Co.Design. “Brian and I really responded to that, as it suggested a specific and interesting way to think about how the books could be designed. We wanted the books to feel like first editions of Moby-Dick or Treasure Island or The Wizard of Oz.”

The tasteful gray cloth binding and foil stamping of the set and its “extremely conventional” design, as Sahre puts it (“maybe ‘comfortable’ would be a better way to describe it,” he adds) makes me think of famous children’s literature collections, like The Chronicles of Narnia. “This ‘traditional/comfortable’ design allowed for the drawings Brian was doing to venture off into the abstract and unconventional place they ended up,” Sahre continues. “More importantly, the quiet design allowed the text and the drawings room to interact and to breathe. I hope the reader doesn’t notice the design of the book at all.”

The set is available on Amazon.

Steve Denning, writing in Forbes:

In today’s paradoxical world of maximizing shareholder value, which Jack Welch himself has called “the dumbest idea in the world”, the situation is the reverse. CEOs and their top managers have massive incentives to focus most of their attentions on the expectations market, rather than the real job of running the company producing real products and services.

Denning is summarizing the ideas contained in Roger Martin’s new book, Fixing the Game: Bubbles, Crashes, and What Capitalism Can Learn from the NFL.

In Fixing the Game, Roger Martin reveals the culprit behind the sorry state of American capitalism: our deep and abiding commitment to the idea that the purpose of the firm is to maximize shareholder value. This theory has led to a massive growth in stock-based compensation for executives and, through this, to a naive and wrongheaded linking of the real market — the business of designing, making, and selling products and services — with the expectations market — the business of trading stocks, options, and complex derivatives. Martin shows how this tight coupling has been engineered and lays out its results: a single-minded focus on the expectations market that will continue driving us from crisis to crisis — unless we act now.

(thx, david)

In an excerpt from the introduction to Subway, his collection of photographs of the NYC subway, Bruce Davidson recalls how he came to start taking photos on the subway in the 1980s.

As I went down the subway stairs, through the turnstile, and onto the darkened station platform, a sinking sense of fear gripped me. I grew alert, and looked around to see who might be standing by, waiting to attack. The subway was dangerous at any time of the day or night, and everyone who rode it knew this and was on guard at all times; a day didn’t go by without the newspapers reporting yet another hideous subway crime. Passengers on the platform looked at me, with my expensive camera around my neck, in a way that made me feel like a tourist-or a deranged person.

Published just a few days after what would become George Orwell’s most well-known novel in 1949, here’s what the New York Times had to say about Nineteen Eighty-Four.

In the excesses of satire one may take a certain comfort. They provide a distance from the human condition as we meet it in our daily life that preserves our habitual refuge in sloth or blindness or self-righteousness. Mr. Orwell’s earlier book, Animal Farm, is such a work. Its characters are animals, and its content is therefore fabulous, and its horror, shading into comedy, remains in the generalized realm of intellect, from which our feelings need fear no onslaught. But ”Nineteen Eighty-four” is a work of pure horror, and its horror is crushingly immediate.

The Millions presents their annual A Year in Reading for 2011, where they ask a bunch of people their favorite reads of the year.

With this in mind, for an eighth year, we asked some of our favorite writers, thinkers, and readers to look back, reflect, and share. Their charge was to name, from all the books they read this year, the one(s) that meant the most to them, regardless of publication date. Grouped together, these ruminations, cheers, squibs, and essays will be a chronicle of reading and good books from every era. We hope you find in them seeds that will help make your year in reading in 2012 a fruitful one.

Contributors include Duff McKagan, Mayim Bialik, Jennifer Egan, Colum McCann, and Rosecrans Baldwin.

In recent years, authors have claimed that many seemingly boring things have changed the world but a particularly strong case can be made for the potato and Charles C. Mann makes it.

The effects of this transformation were so striking that any general history of Europe without an entry in its index for S. tuberosum should be ignored. Hunger was a familiar presence in 17th- and 18th-century Europe. Cities were provisioned reasonably well in most years, their granaries carefully monitored, but country people teetered on a precipice. France, the historian Fernand Braudel once calculated, had 40 nationwide famines between 1500 and 1800, more than one per decade. This appalling figure is an underestimate, he wrote, “because it omits the hundreds and hundreds of local famines.” France was not exceptional; England had 17 national and big regional famines between 1523 and 1623. The continent simply could not reliably feed itself.

The potato changed all that. Every year, many farmers left fallow as much as half of their grain land, to rest the soil and fight weeds (which were plowed under in summer). Now smallholders could grow potatoes on the fallow land, controlling weeds by hoeing. Because potatoes were so productive, the effective result, in terms of calories, was to double Europe’s food supply.

Mann talks more about the potato in his excellent 1493: Uncovering the New World Columbus Created.

Richard Rhodes, author of two of my favorite books of all time (Making of the Atomic Bomb and Dark Sun), has written a book about one of the most intriguing people of the 20th century, Hedy Lamarr, big-time Hollywood bombshell and inventor of a frequency-hopping spread-spectrum communication system.

Hedwig (Hedy) Kiesler may be one of the greatest unsung heroes of twentieth century technological progress. An opportunistic Austrian immigrant driven by curiosity and a desire to make it as a Hollywood actress in the early years of World War II, Hedy worked with avant-garde composer George Antheil to create the technology that we depend upon today for cell phones and GPS: frequency hopping. Though Richard Rhodes presents details about everyone involved in the separate experiences that the two inventors drew upon to make their breakthrough in Hedy’s Folly, the invention itself takes center stage, driving the remarkable story with precision. Rhodes skillfully weaves together all the disparate parts of the story, from how Hedy learned about Nazi torpedoes to why George’s knowledge of player pianos was key to the invention, in order to create a highly readable genesis of the technology that influences billions of lives every day.

Now that the folks at Next Restaurant are done with their initial menu (Paris, 1906), they’re giving it all away in a cookbook available exclusively for iBooks. And they’re going to do the same thing for each of their menus.

Next is a restaurant like no other. Every season the menu and service explore an entirely different cuisine. Buying a ticket is the only way to get in… and the entire season sold out in a few hours. The inaugural menu took diners back to Paris: 1906, Escoffier at the Ritz for a multi-course pre fixe dinner that was described by the New York Times as “Belle Epoque dishes largely unseen on American tables for generations.”

Ok, someone needs to do this: 1. Open a restaurant (in New York, say) that features old menus from Next every three months using the Next cookbooks to plan menus. 2. Call it Previous. 3. Profit!

In a review of Walter Isaacson’s biography of Steve Jobs, Malcolm Gladwell says that Jobs was much more of a “tweaker” than an inventor…he took ideas from others and made them better.

Jobs’s sensibility was editorial, not inventive. His gift lay in taking what was in front of him-the tablet with stylus-and ruthlessly refining it. After looking at the first commercials for the iPad, he tracked down the copywriter, James Vincent, and told him, “Your commercials suck.”

“Well, what do you want?” Vincent shot back. “You’ve not been able to tell me what you want.”

“I don’t know,” Jobs said. “You have to bring me something new. Nothing you’ve shown me is even close.”

Vincent argued back and suddenly Jobs went ballistic. “He just started screaming at me,” Vincent recalled. Vincent could be volatile himself, and the volleys escalated.

When Vincent shouted, “You’ve got to tell me what you want,” Jobs shot back, “You’ve got to show me some stuff, and I’ll know it when I see it.”

HBO is doing a show (or is it a movie?) based on Jonathan Franzen’s The Corrections.

With 2 Oscar winners, Chris Cooper and Diane Wiest, already cast as the leads, this was a no-brainer, but it’s now official: HBO’s drama pilot The Corrections is proceeding to production.

Oliver Stone is set to direct a movie for HBO based on Robert Caro’s biography of Robert Moses, The Power Broker.

Moses, who at one time was dubbed the city’s “master builder,’ was among the most powerful men in 20th century urban planning and politics, having influenced New York’s infrastructure as much as any other individual.

The story says it’ll be a movie, but how are they going to cram the 1344 pages of The Power Broker into 120 minutes? It’ll be a multi-parter, surely. (via ★al)

You can’t believe how excited my four-year-old was at the arrival of this book last night. He read it this morning as he ate his breakfast, quiet as a stone, save for the occasional “daddy, look at this!” outburst.

From 1958, a piece from Fortune magazine written by Jane Jacobs called Downtown is for People.

There are, certainly, ample reasons for redoing downtown—falling retail sales, tax bases in jeopardy, stagnant real-estate values, impossible traffic and parking conditions, failing mass transit, encirclement by slums. But with no intent to minimize these serious matters, it is more to the point to consider what makes a city center magnetic, what can inject the gaiety, the wonder, the cheerful hurly-burly that make people want to come into the city and to linger there. For magnetism is the crux of the problem. All downtown’s values are its byproducts. To create in it an atmosphere of urbanity and exuberance is not a frivolous aim.

Jacobs’ classic The Death and Life of Great American Cities came out 50 years ago.

My copy of Walter Isaacson’s authorized biography of Steve Jobs just showed up on my Kindle and many other people are reporting the same on Twitter. The book is also available as a hardcover.

Using Jeffrey Eugenides’s newest book, The Marriage Plot, as a jumping-off point, Evan Hughes explores how the personal relationships and jealousies amongst a cadre of writers that included Eugenides, Rick Moody, Jonathan Franzen, Mary Karr, and David Foster Wallace pushed each of them to produce their best work and plumb the lowest depths of their self-loathing.

It was another novel-in-manuscript that had propelled Franzen toward his new phase — the thousand-plus pages of Infinite Jest. Almost all of what Franzen had read at the Limbo had been written in a kind of response to Wallace after getting an early look at his groundbreaking book. “I felt, Shit, this guy’s really done it.” As Franzen saw it, Wallace had managed to incorporate the kind of broad-canvas social critique that the great postmodernists did into a narrative “of deadly personal pertinence.” The pages Franzen produced then, he says, “came out of trying to feel good about myself as a writer after what an achievement Infinite Jest was.” His comments to Wallace weren’t all sunshine, though; he also “pointed toward some plot problems.” Wallace granted that the problems existed, Franzen told me, but said that he would thereafter deny ever having admitted it.

Nevertheless, Franzen knew it was “a giant book,” an end point of sorts. “It was clear that it was not going to be appropriate of me to try to compete at the level of rhetoric and the level of formal invention that he had achieved.” He turned instead to “a family story about a midwestern Christmas,” the beginning of which he read at the Limbo. The result was The Corrections.

A version of Food Rules by Michael Pollan illustrated by Maira Kalman? Hell yeah!

Michael Pollan and Maira Kalman come together to create an enhanced Food Rules for hardcover, now beautifully illustrated and with even more food wisdom.

Michael Pollan’s definitive compendium, Food Rules, is here brought to colorful life with the addition of Maira Kalman’s beloved illustrations.

This brilliant pairing is rooted in Pollan’s and Kalman’s shared appreciation for eating’s pleasures, and their understanding that eating doesn’t have to be so complicated. Written with the clarity, concision, and wit that is Michael Pollan’s trademark, this indispensable handbook lays out a set of straightforward, memorable rules for eating wisely. Kalman’s paintings remind us that there is delight in learning to eat well.

Newer posts

Older posts

Stay Connected