kottke.org posts about books

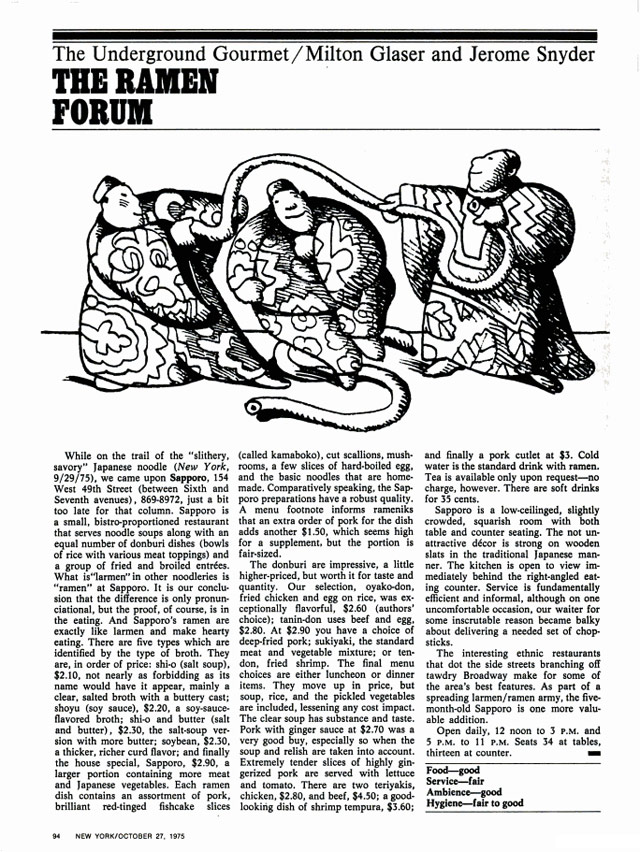

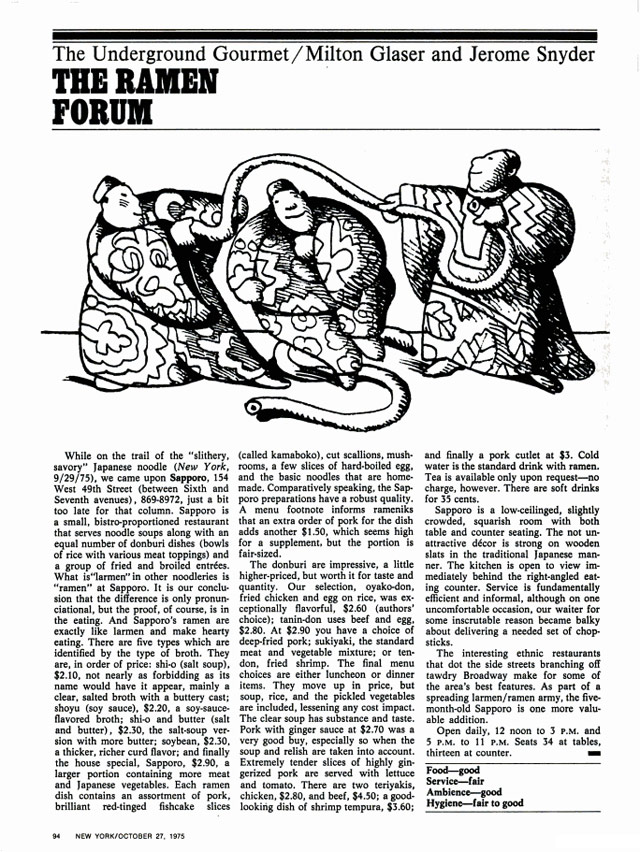

Today I learned that iconic designer Milton Glaser co-wrote a column for New York magazine (which he co-founded) about where to find cheap-but-good food in NYC. It was called The Underground Gourmet. Here’s a typical column from the October 27, 1975 issue, reviewing a ramen joint in Midtown called Sapporo that is miraculously still around:

Glaser and his co-authior Jerome Snyder eventually packaged the column into a series of books, some of which you can find on Amazon…I bought a copy this morning.

I found out about Glaser’s food enthusiasm from this interview in Eye magazine about The Underground Gourmet and his long collaboration with restaurateur Joe Baum of the Rainbow Room and Windows on the World.

We just walked the streets … When friends of ours knew we were doing it we got recommendations.

There were parts of the city where we knew we could find good places … particularly in the ethnic parts. We knew if we went to Chinatown we would find something if we looked long enough, or Korea Town, or sections of Little Italy.

More then than now, the city was more locally ethnic before the millionaires came in and bought up every inch of space. So you could find local ethnic places all over the city. And people were dying to discover that. And it was terrific to be able to find a place where you could have lunch for four dollars.

In 2010, Josh Perilo wrote an appreciation of The Underground Gourmet in which he noted only six of the restaurants reviewed in the 1967 edition had survived:

Being obsessed with the food and history of New York (particularly Manhattan), this was like finding a culinary time capsule. I immediately dove in. What I found was shocking, both in the similarities between then and now, and in the differences.

The most obvious change was the immense amount of restaurants that no longer existed. These were not landmarked establishments, by and large. Most of them were hole-in-the wall luncheonettes, inexpensive Chinese restaurants and greasy spoons. But the sheer number of losses was stunning. Of the 101 restaurants profiled, only six survive today: Katz’s Delicatessen, Manganaro’s, Yonah Schimmel’s Knishes Bakery, The Puglia and La Taza de Oro. About half of the establishments were housed in buildings that no longer exist, especially in the Midtown area. The proliferation of “lunch counters” also illustrated the evolution of this city’s eating habits. For every kosher “dairy lunch” joint that went down, it seems as though a Jamba Juice or Pink Berry has taken its place.

Man, it’s hard not get sucked into reading about all these old places…looking forward to getting my copy of the book in a week or two.

Update: Glaser’s co-author Jerome Snyder was also a designer…and no slouch either.

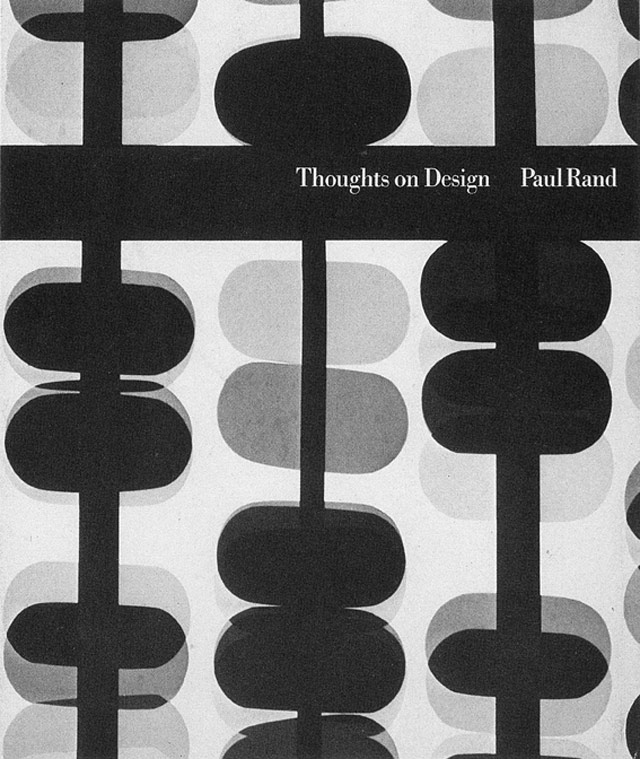

Legendary designer Paul Rand’s Thoughts on Design is back in print for the first time since the 1970s. The new version, which will be out on Aug 19, is available for preorder and comes with a foreword by Michael Bierut.

One of the seminal texts of graphic design, Paul Rand’s Thoughts on Design is now available for the first time since the 1970s. Writing at the height of his career, Rand articulated in his slender volume the pioneering vision that all design should seamlessly integrate form and function. This facsimile edition preserves Rand’s original 1947 essay with the adjustments he made to its text and imagery for a revised printing in 1970, and adds only an informative and inspiring new foreword by design luminary Michael Bierut. As relevant today as it was when first published, this classic treatise is an indispensable addition to the library of every designer.

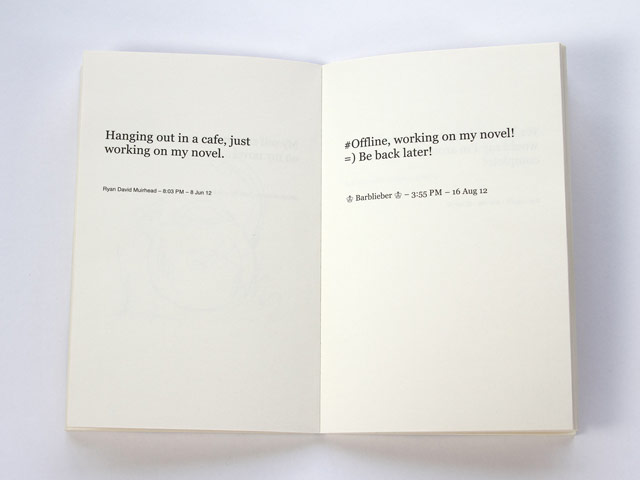

From artist Cory Arcangel, Working On My Novel is a book comprised of tweets from people who posted they were working on their novels.

What does it feel like to try and create something new? How is it possible to find a space for the demands of writing a novel in a world of instant communication? Working on My Novel is about the act of creation and the gap between the different ways we express ourselves today. Exploring the extremes of making art, from satisfaction and even euphoria to those days or nights when nothing will come, it’s the story of what it means to be a creative person, and why we keep on trying.

Arcangel also ran a blog that reposted “I’m sorry I haven’t posted” posts from other blogs.

For August, the writers at HiLobrow will have a month of appreciations of fonts and typefaces, lovingly titled “Kern Your Enthusiasm.” Matthew Battles kicks things off with the legendary Aldine Italic developed for Venetian publisher Aldus Manutius, a new set of metal letters that helped jumpstart a little thing we call the Renaissance.

When Aldus put the first version of a typeface we call italic to use in 1501, the printing press had been proliferating in Europe for half a century. In other words, it was about as old as the computer is now. It was a time of immense invention and swiftly spun variety in the printed book, and a time of new mobility and independence of thought and activity among certain classes of people as well — and the combination of new ways and new tools meant new kinds of books. Crucially, the book was getting smaller, small enough to act not only as a desktop, but as a mobile device.

Previous HiLobrow series include “Kirb Your Enthusiasm” (on Jack Kirby), “Kirk Your Enthusiasm” (on Star Trek’s Captain Kirk) and “Herc Your Enthusiasm” (on old school hip-hop, where I contributed a short thing on Afrika Bambaataa.)

Hi, everybody! Tim Carmody here, guest-hosting for Jason this week.

Not everybody gives their computers, smartphones, or wireless networks distinctive names. You’re more likely to see a thousand public networks named “Belkin” or some alphanumeric gibberish than one named after somebody’s favorite character in The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy.

But many, many people do name their machines — and ever since we slid into the post-PC era, we’re more likely to have a bunch of different machines of every different type living together on a network, each needing a name. So, how do you decide what to call them? Do you just pick what strikes your fancy at the moment, or do you have a system?

About three years ago, I asked my friends and followers on Twitter this question and got back some terrific responses. I don’t have access to all of their answers, because, well, time makes fools of us all, especially on Twitter. But I think I have the best responses.

Most people who wrote back did have unifying themes for their machines. And sweet Jesus, are those themes nerdy.

- A lot of people name their computers, networks, and hard drives after characters, places, and objects from Star Wars. Like, a lot of them.

- Even more of my friends name devices after their favorite books and writers. My favorite of these came from @DigDoug: “All of my machines are named after characters in Don Quixote. My Macbook is Dulcinea, the workhorse is Rocinante.” (Note: these systems are also popular among my friends for naming their cats. I don’t know what to make of that.)

- Science- and mythology-inspired names are well-represented. Mathias Crawford’s hard drives are named after types of penguins; Alan Benzie went with goddesses: “The names Kali, Isis, Eris, Juno, Lilith & Hera are distributed around whatever devices and drives I have at any time.” (When I first read this, I thought these might have been moons of Jupiter, which would both split the difference between science and mythology and would be a super-cool way to name your stuff.)

- Wi-fi networks might be named for places, funny phrases, or abstract entities, but when it comes to phones or laptops, most people seemed to pick persons’ names. Oliver Hulland’s hard drives were all named after muppets; Alex Hern named his computer’s hard drive and its time capsule backup Marx and Engels, respectively.

- Some people always stuck with the same system, and sometimes even the same set of names. A new laptop would get the same name as the old laptop, and so forth — like naming a newborn baby after a dead relative. Other people would retire names with the devices that bore them. They still refer to them by their first names, often with nostalgia and longing.

As for me, I’ve switched up name systems over the years, mostly as the kinds of devices on my network have changed. I used to just have a desktop PC (unnamed), so I started out by naming external hard drives after writers I liked: Zora, after Zora Neale Hurston, and then Dante. The first router I named, which I still have, is Ezra.

Years later, I named my laptop “Wallace”: this is partly for David Foster Wallace, but also so I could yell “where the fuck is Wallace?!?” whenever I couldn’t find it.

Without me even realizing it, that double meaning changed everything. My smartphone became “Poot.” When I got a tablet, it was “Bodie.” My Apple TV was “Wee-Bay,” my portable external drive “Stringer.” I even named my wi-fi network “D’Angelo” — so now D’Angelo runs on Ezra, which connects to Dante, if that makes sense.

As soon as it was Wallace and Poot, the rules were established: not just characters from The Wire, but members of the Barksdale crew from the first season of The Wire. No “Bunk,” no “Omar,” no “Cheese.” And when the machines died, their names died with them.

The first one to go, fittingly, was Wallace. I called the new machine “Cutty.” I was only able to justify to myself by saying that because he was a replacement machine, it was okay to kick over to Season 3. Likewise, my Fitbit became “Slim Charles.”

Now, for some reason, this naming scheme doesn’t apply at all to my Kindles. My first one was “Tlon, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius,” and its replacement is “Funes the Memorious.” I have no explanation for this, other than to say that while all my other devices commingle, the Kindles seem to live in a hermetic world of their own.

Explaining Hitler is a 1998 book by Ron Rosenbaum that compiled a number of different theories about why Adolf Hitler was the way he was, updated recently with new information.

Hitler did not escape the bunker in Berlin but, seven decades later, he has managed to escape explanation in ways both frightening and profound. Explaining Hitler is an extraordinary quest, an expedition into the war zone of Hitler theories. This is a passionate, enthralling book that illuminates what Hitler explainers tell us about Hitler, about the explainers, and about ourselves.

Vice recently interviewed Rosenbaum about the book.

Oh my God, there are so many terrible psychological attempts to explain Hitler. I think the subject brings out the worst in talk show psychologists. There’s a lot of ‘psychopathic narcissism’ among those psychologizing Hitler. The examples in my book were two psychoanalysts-one wanted to claim that Hitler became Hitler because he was beaten by his father, and the other psychoanalyst was equally determined to believe that Hitler had a malignant mother who was over-protective. As if everyone who has an over-protective mother or abusive father turns into Hitler. If everyone who has been struck by their father turned into Hitler we would be in a lot more trouble than we are.

Related by not related: Rosenbaum wrote a story in 1971 for Esquire about phone phreaking, Secrets of the Little Blue Box, which inspired the very first partnership between a pair of young future tech titans, Steve Wozniak and Steve Jobs. (via @errolmorris)

Update: Rosenbaum talks about Explaining Hitler on the Virtual Memories podcast.

From a pair of science historians, Naomi Oreskes and Erik Conway, comes The Collapse of Western Civilization: A View from the Future, a book of science fiction about the consequences of climate change.

The year is 2393, and a senior scholar of the Second People’s Republic of China presents a gripping and deeply disturbing account of how the children of the Enlightenment, the political and economic elites of the so-called advanced industrial societies, entered into a Penumbral period in the early decades of the twenty-first century, a time when sound science and rational discourse about global change were prohibited and clear warnings of climate catastrophe were ignored. What ensues when soaring temperatures, rising sea levels, drought, and mass migrations disrupt the global governmental and economic regimes? The Great Collapse of 2093.

Update: In the same vein is Steven Amsterdam’s Things We Didn’t See Coming.

Richly imagined, dark, and darkly comic, the stories follow the narrator over three decades as he tries to survive in a world that is becoming increasingly savage as cataclysmic events unfold one after another. In the first story, “What We Know Now” — set in the eve of the millennium, when the world as we know it is still recognizable — we meet the then-nine-year-old narrator fleeing the city with his parents, just ahead of a Y2K breakdown. The remaining stories capture the strange — sometimes heartbreaking, sometimes funny — circumstances he encounters in the no-longer-simple act of survival; trying to protect squatters against floods in a place where the rain never stops, being harassed (and possibly infected) by a man sick with a virulent flu, enduring a job interview with an unstable assessor who has access to all his thoughts, taking the gravely ill on adventure tours.

(thx, matty)

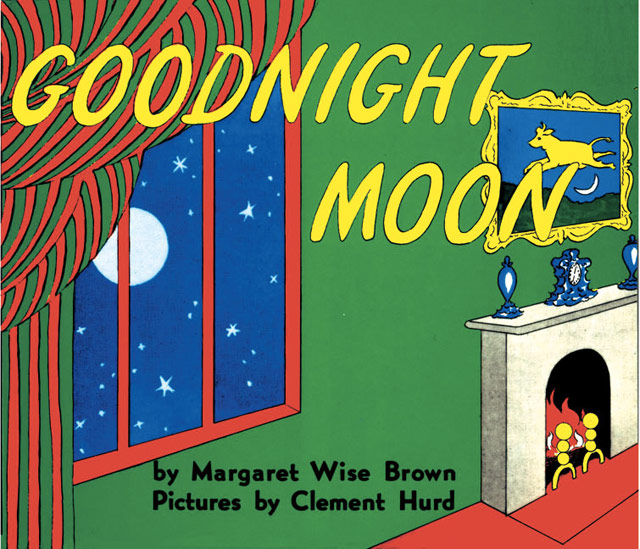

From Aimee Bender, an appreciation of Margaret Wise Brown’s Goodnight Moon, a favorite of mine to read to my kids when they were younger.

“Goodnight Moon” does two things right away: It sets up a world and then it subverts its own rules even as it follows them. It works like a sonata of sorts, but, like a good version of the form, it does not follow a wholly predictable structure. Many children’s books do, particularly for this age, as kids love repetition and the books supply it. They often end as we expect, with a circling back to the start, and a fun twist. This is satisfying but it can be forgettable. Kids - people - also love depth and surprise, and “Goodnight Moon” offers both.

Haven’t read Goodnight Moon in ages…at 4 and 7, my kids protest whenever I suggest it. We’re currently powering our way through the third Harry Potter book, which, though I enjoy Potter, is no Goodnight Moon.

Update: How Goodnight Moon overcame bad initial reviews and became a word-of-mouth bestseller.

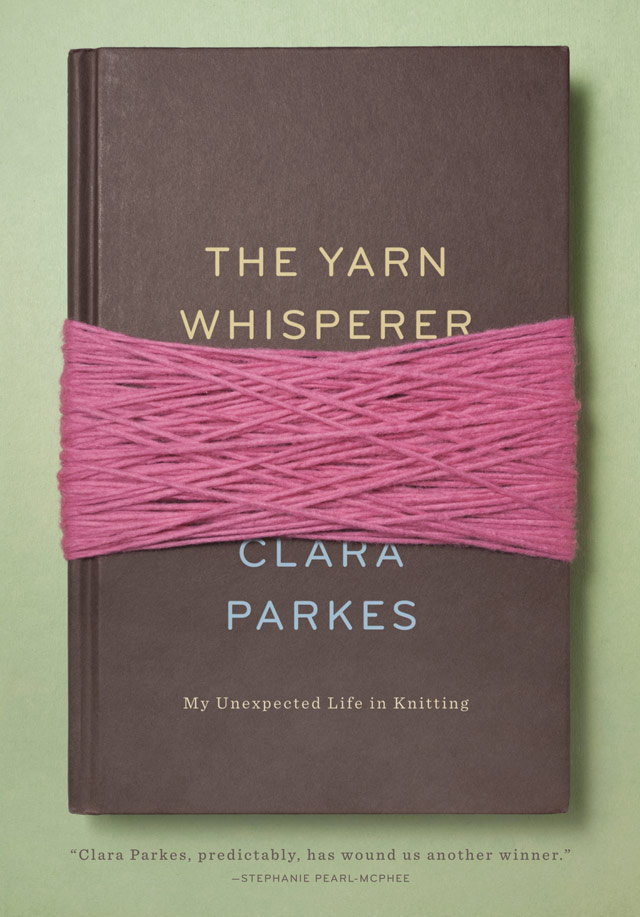

An extensive collection of book covers featuring books. Confused? Maybe an example will help:

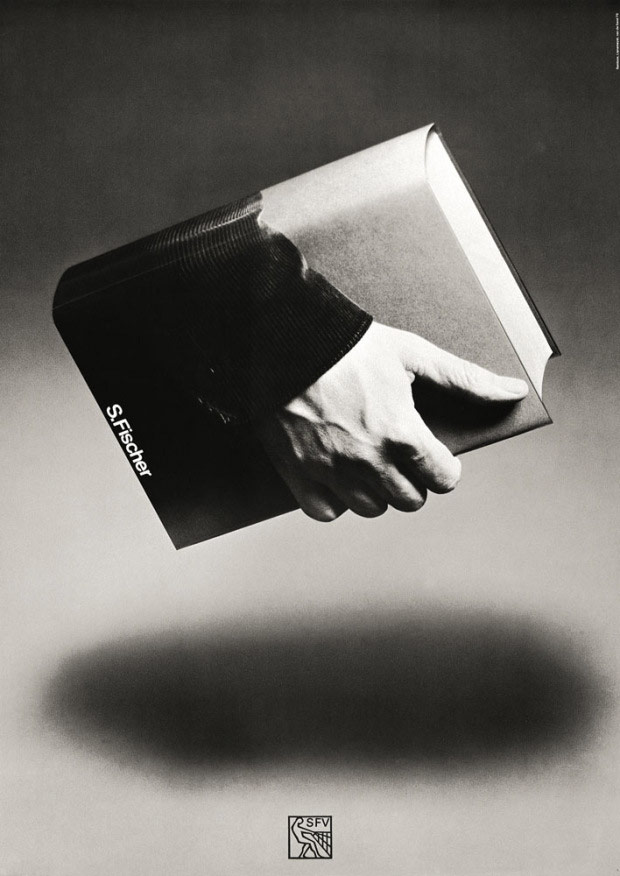

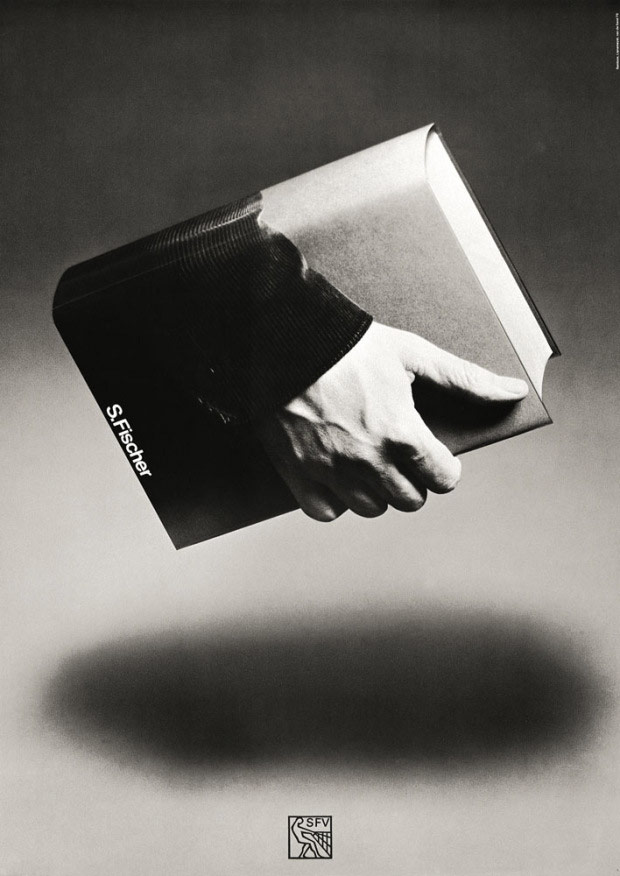

I love these book posters by Gunter Rambow from the 1970s, especially this one:

(via @michaelbierut)

From Portraits in Creativity, a video profile of Maira Kalman, doer of many wonderful things.

Kalman’s newest book is Girls Standing on Lawns, a collaboration with MoMA and Daniel Handler (aka Lemony Snicket).

This clever book contains 40 vintage photographs from the collection of The Museum of Modern Art, New York, more than a dozen original paintings by Kalman inspired by the photographs, and brief, lyrical texts by Handler. Poetic and thought-provoking, Girls Standing on Lawns is a meditation on memories, childhood, nostalgia, home, family, and the act of seeing.

I once saw Kalman while I was eating lunch with my son in the cafe on the second floor of MoMA. She came in and sat opposite us a few tables away and started sketching. What a thrill to watch her work. (via @curiousoctopus)

If you’ve been paying attention to the promos for HBO’s Game of Thrones series, there’s been a lot of Jon Snow sitting on the Iron Throne. When the show started, Snow seemed like a relatively minor character, but his uncertain parentage hinted at possible greater things on the horizon. Here’s a video explanation of one of the more popular theories about Snow’s parents:

BTW, if you, like me, haven’t read the books and have only seen the TV show, the video doesn’t contain any outright spoilers, only enriching context. So watch away. And if you’ve read the books, you probably don’t need to watch the video because you’re probably already aware of this old theory. If you’re interested, there are more theories (and crazy spoilers) where that came from.

Earlier today I asked my Twitter followers for recommendations for “really good” biographies about scientists. I gave Genius (James Gleick’s bio of Richard Feynman) and Cleopatra, A Life (not about a scientist but was super interesting and well-written) as examples of what I was looking for. You can see the responses here and I’ve pulled out a few of the most interesting ones below:

- Isaac Newton by James Gleick. Gleick wrote the aforementioned Genius and Chaos, another favorite of mine. I tried to read The Information last year after many glowing recommendations from friends but couldn’t get into it. Someone suggested Never at Rest is a superior Newton bio.

- The Man Who Loved Only Numbers by Paul Hoffman. I’ve read this biography of mathematician Paul Erdos; highly recommended.

- Galileo’s Daughter by Dava Sobel. I’ve never read anything by Sobel; I’ll have to rectify that.

- Einstein: His Life and Universe by Walter Isaacson. I enjoyed his problematic Jobs biography and I notice that he’s written one on Ben Franklin as well.

- Alan Turing: The Enigma by Andrew Hodges.

- American Prometheus by Kai Bird and Martin Sherwin. Bio of J. Robert Oppenheimer, leader of the Manhattan Project. See also: The Making of the Atomic Bomb, one of my favorite books ever.

- Everything and More by David Foster Wallace. I’ve heard Wallace was bit handwavy with the math in this one, but I still enjoyed it.

- Newton and the Counterfeiter by Thomas Levenson. Newton was a detective?

- The Philosophical Breakfast Club by Laura Snyder. Four-way bio of a group of school friends (Charles Babbage, John Herschel, William Whewell, and Richard Jones) who changed the world.

- The Reluctant Mr. Darwin by David Quammen. How Charles Darwin devised his theory of evolution and then sat on it for years is one of science’s most fascinating stories.

- T. rex and the Crater of Doom by Walter Alvarez. Not a biography of a person but of a theory: that a meteor impact 65 million years ago caused the extinction of the dinosaurs.

- Walt Disney by Neal Gabler. Disney isn’t a scientist, but when you ask for book recommendations and Steven Johnson tells you to read something, it goes on the list.

- The Man Who Knew Infinity by Robert Kanigel. Bio of brilliant Indian mathematician Srinivasa Ramanujan.

- Edge of Objectivity by Charles Gillispie. A biography of modern science published in 1966, all but out of print at this point unfortunately.

- Galileo at Work by Stillman Drake.

- The Age of Wonder by Richard Holmes.

And many more here. Thanks to everyone who suggested books.

Update: Because this came up on Twitter, some biographies specifically about women in science: The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, Hedy’s Folly, On a Farther Shore, Marie Curie: A Life, A Feeling for the Organism, Rosalind Franklin: The Dark Lady of DNA, Jane Goodall: The Woman Who Redefined Man, and Radioactive.

Inspired by Halt and Catch Fire, I’m re-reading Tracy Kidder’s The Soul of a New Machine. I had forgotten how good this book is. Man. The story follows an engineering team at Data General as they attempt to design and build an entirely new minicomputer in the late 1970s. Kidder won a Pulitzer and a National Book Award for this book.

The Atlantic published two lengthy excerpts of the book back in 1981 — Flying Upside Down and The Ultimate Toy — but if those catch your fancy at all, I’d recommend skipping them and just read the book.

One holiday morning in 1978, Tom West traveled to a city that was situated, he would later say guardedly, “somewhere in America.” He entered a building as though he belonged there, strolled down a hallway, and let himself quietly into a windowless room. Just inside the door, he stopped.

The floor was torn up; a shallow trench filled with fat power cables traversed it. Along the far wall, at the end of the trench, enclosed in three large, cream-colored steel cabinets, stood a VAX 11/780, the most important of a new class of computers called “32-bit superminis.” To West’s surprise, one of the cabinets was open and a man with tools was standing in front of it. A technician, still installing the machine, West figured.

Although West’s designs weren’t illegal, they were sly, and he had no intention of embarrassing the friend who had told him he could visit this room. If the technician had asked West to identify himself, West wouldn’t have lied and he wouldn’t have answered the question, either. But the moment went by. The technician didn’t inquire. West stood around and watched him work, and in a little while the technician packed up his tools and left.

Then West closed the door and walked back across the room to the computer, which was now all but fully assembled. He began to take it apart.

West was the leader of a team of computer engineers at a company called Data General. The machine that he was disassembling was produced by a rival firm, Digital Equipment Corporation, or DEC. A VAX and a modest amount of adjunctive equipment sold for something like $200,000, and as West liked to say, DEC was beginning to sell VAXes “like jellybeans.” West had traveled to this room to find out for himself just how good this computer was, compared with the one that his team was building.

Just after Infinite Jest was published, David Foster Wallace came to Boston and did a radio interview with Chris Lydon. Radio Open Source recently unearthed that interview, probably unheard for the past 18 years, and published it on their site.

When I started the book the only idea I had is I wanted to do something about America that was sad but wasn’t just making fun of America. Most of my friends are extremely bright, privileged, well-educated Americans who are sad on some level, and it has something, I think, to do with loneliness. I’m talking out of my ear a little bit, this is just my opinion, but I think somehow the culture has taught us or we’ve allowed the culture to teach us that the point of living is to get as much as you can and experience as much pleasure as you can, and that the implicit promise is that will make you happy. I know that’s almost offensively simplistic, but the effects of it aren’t simplistic at all.

There haven’t been many good books written about soccer, but here are eleven of them worth your time. Franklin Foer’s How Soccer Explains the World: An Unlikely Theory of Globalization looks especially interesting.

A groundbreaking work — named one of the five most influential sports books of the decade by Sports Illustrated — How Soccer Explains the World is a unique and brilliantly illuminating look at soccer, the world’s most popular sport, as a lens through which to view the pressing issues of our age, from the clash of civilizations to the global economy.

Foer is one of the contributors, alongside authors Aleksandar Hemon and Karl Ove Knausgaard, to the New Republic’s excellent World Cup coverage.

I missed this news a couple of months ago: Steven Spielberg is going to direct a movie version of Roald Dahl’s The BFG.

Renowned film director Steven Spielberg will direct the new adaptation with Melissa Mathison, who last worked with Spielberg on ET, writing the script. Frank Marshall will produce the film and Michael Siegel and John Madden are on board as executive producers.

I can’t find any direct evidence, but the way the news is being reported, this seems like it’ll be a live-action film and not a Tintin 3-D motion capture affair.

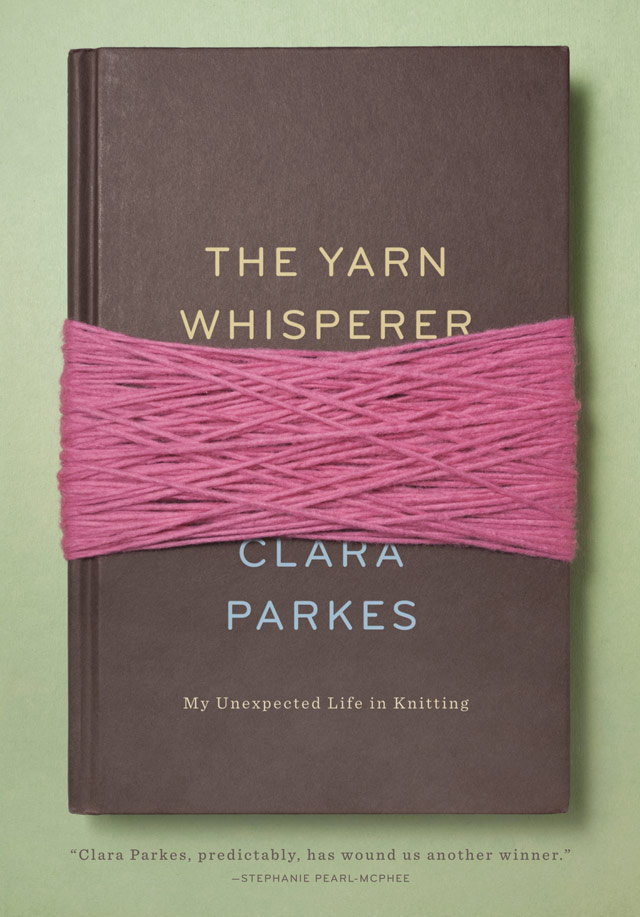

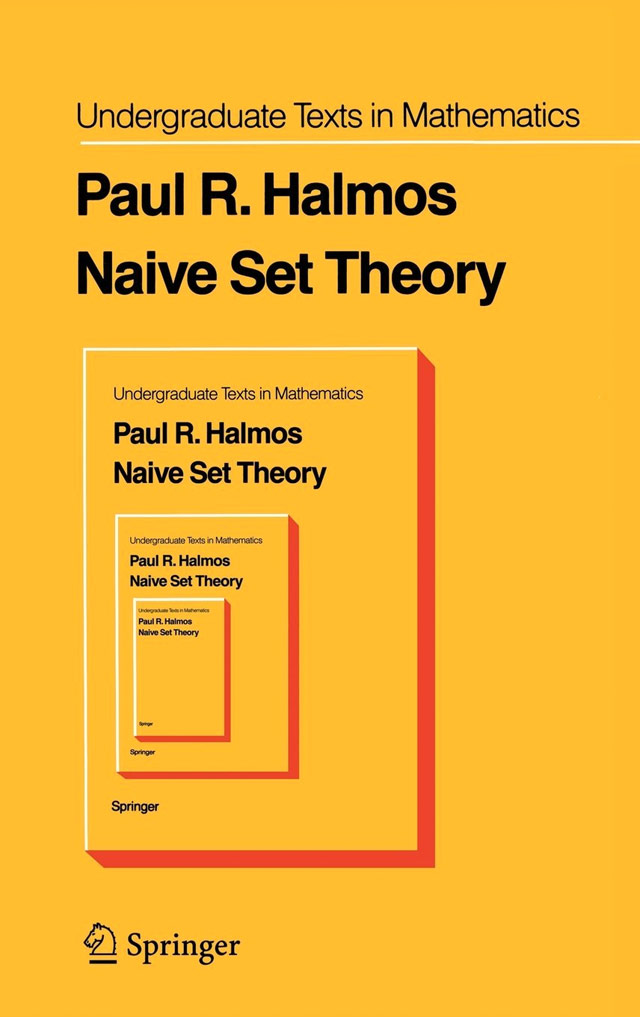

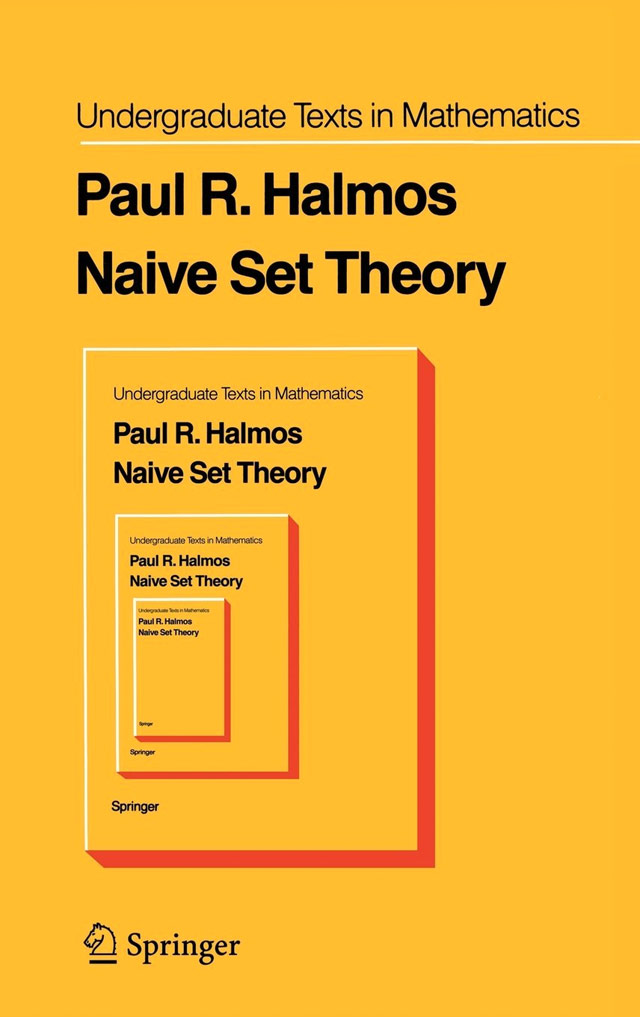

The book cover for Naive Set Theory by Paul Halmos is so so good:

The cover is a riff on, I think, Russell’s Paradox, a problem with naive set theory described by Bertrand Russell in 1901 about whether sets can contain themselves.

Russell’s paradox is based on examples like this: Consider a group of barbers who shave only those men who do not shave themselves. Suppose there is a barber in this collection who does not shave himself; then by the definition of the collection, he must shave himself. But no barber in the collection can shave himself. (If so, he would be a man who does shave men who shave themselves.)

Reminds me of David Pearson’s genius cover for Benjamin’s The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction.

Paul Greenberg has an excerpt in the NY Times of his new book, American Catch: The Fight for Our Local Seafood.

As go scallops, so goes the nation. According to the National Marine Fisheries Service, even though the United States controls more ocean than any other country, 86 percent of the seafood we consume is imported.

But it’s much fishier than that: While a majority of the seafood Americans eat is foreign, a third of what Americans catch is sold to foreigners.

The seafood industry, it turns out, is a great example of the swaps, delete-and-replace maneuvers and other mechanisms that define so much of the outsourced American economy; you can find similar, seemingly inefficient phenomena in everything from textiles to technology. The difference with seafood, though, is that we’re talking about the destruction and outsourcing of the very ecological infrastructure that underpins the health of our coasts.

The article and book focus on three formerly American seafoods that we now mostly import from elsewhere: salmon, oysters, and shrimp.

In 2005, the United States imported five billion pounds of seafood, nearly double what we imported twenty years earlier. Bizarrely, during that same period, our seafood exports quadrupled. American Catch examines New York oysters, Gulf shrimp, and Alaskan salmon to reveal how it came to be that 91 percent of the seafood Americans eat is foreign.

In the 1920s, the average New Yorker ate six hundred local oysters a year. Today, the only edible oysters lie outside city limits. Following the trail of environmental desecration, Greenberg comes to view the New York City oyster as a reminder of what is lost when local waters are not valued as a food source.

Farther south, a different catastrophe threatens another seafood-rich environment. When Greenberg visits the Gulf of Mexico, he arrives expecting to learn of the Deepwater Horizon oil spill’s lingering effects on shrimpers, but instead finds that the more immediate threat to business comes from overseas. Asian-farmed shrimp-cheap, abundant, and a perfect vehicle for the frying and sauces Americans love-have flooded the American market.

Finally, Greenberg visits Bristol Bay, Alaska, home to the biggest wild sockeye salmon run left in the world. A pristine, productive fishery, Bristol Bay is now at great risk: The proposed Pebble Mine project could undermine the very spawning grounds that make this great run possible. In his search to discover why this precious renewable resource isn’t better protected, Greenberg encounters a shocking truth: the great majority of Alaskan salmon is sent out of the country, much of it to Asia. Sockeye salmon is one of the most nutritionally dense animal proteins on the planet, yet Americans are shipping it abroad.

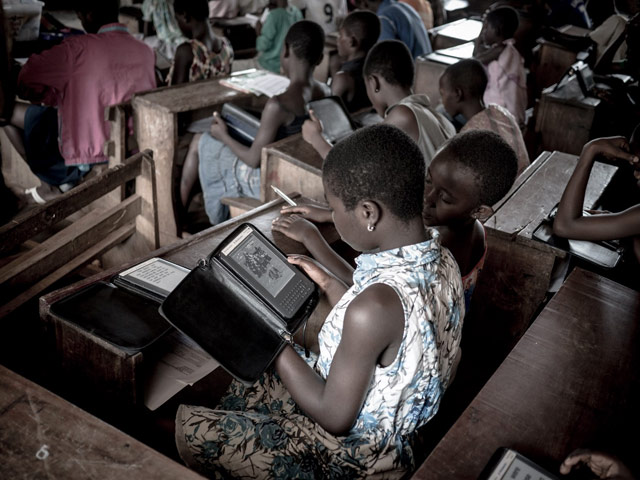

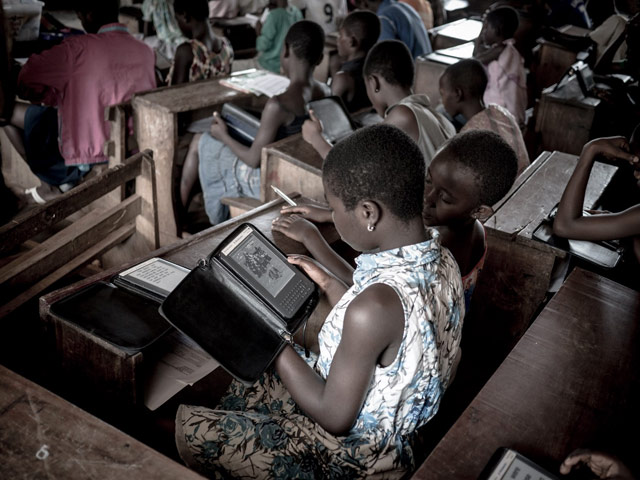

Craig Mod visited Ghana recently to check on the progress of Worldreader, an organization dedicated to distributing digital books to children and families in places like Rwanda, Ghana, and South Africa.

Those of us who work in technology tend to take religious-like stances over its ability to change the world, always for the better. My paranoia of trickery comes from an inherent suspicion towards technology, and an even deeper suspicion of presuming to know better. It’s too easy to fall into the first-world trope of “all the poor need is a little sprinkling of silicon and then everything will be fine.” It’s never that simple. Technology is, at best, the tip of the iceberg. A very tiny component of the work that needs to be done in the greater whole of reforming or impacting or increasing accessibility to education, first-world and third-world alike. Technology deployed without infrastructure, without understanding, without administrative or community support, without proper curriculum is nearly worthless. Worse than worthless, even — for it can be destructive, the time and budget spent on the technology eating into more fundamental, more meaningful points of badly needed reform.

The Mozart Project is a book about the life and music of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. Or is it an app? Stephen Fry calls it “a completely new kind of book”…you read it in iBooks but it acts more like an app than anything. Over 200 pages of text by leading Mozart scholars is accompanied by hours of music, videos, photo slideshows, all sorts of other goodies.

Curated and authored by some of the most respected experts, The Mozart Project gives new insight into the life of a musical genius, providing the ultimate experience both in terms of contributors and the carefully selected playlist of music and images that they have chosen to feature throughout the book.

After thumbing through a copy at my local bar the other night, I’ve had my eye on Jeffrey Morgenthaler’s new book, The Bar Book: Elements of Cocktail Technique.

Written by renowned bartender and cocktail blogger Jeffrey Morgenthaler, The Bar Book is the only technique-driven cocktail handbook out there. This indispensable guide breaks down bartending into essential techniques, and then applies them to building the best drinks. More than 60 recipes illustrate the concepts explored in the text, ranging from juicing, garnishing, carbonating, stirring, and shaking to choosing the correct ice for proper chilling and dilution of a drink. With how-to photography to provide inspiration and guidance, this book breaks new ground for the home cocktail enthusiast.

I’ve been beefing up my home bar over the past few weeks and hopefully this book will help me along in the technique department. Nothing in there about catching glasses behind your back, but no book is perfect, I guess. (thx, gabe)

Alex Wright previously wrote about Paul Otlet (and many other things) in his 2007 book Glut (my post about the book is here). Otlet imagined something like personal computing and the internet back in the 1930s.

Here, the workspace is no longer cluttered with any books. In their place, a screen and a telephone within reach. Over there, in an immense edifice, are all the books and information. From there, the page to be read, in order to know the answer to the question asked by telephone, is made to appear on the screen. The screen could be divided in half, by four, or even ten if multiple texts and documents had to be consulted simultaneously. There would be a loudspeaker if the image had to be complemented by oral data and this improvement could continue to the automating the call for onscreen data. Cinema, phonographs, radio, television: these instruments, taken as substitutes for the book, will in fact become the new book, the most powerful works for the diffusion of human thought. This will be the radiated library and the televised book.

Wright is back with a new book called Cataloging the World in which Otlet takes center stage.

In Cataloging the World, Alex Wright introduces us to a figure who stands out in the long line of thinkers and idealists who devoted themselves to the task. Beginning in the late nineteenth century, Paul Otlet, a librarian by training, worked at expanding the potential of the catalog card, the world’s first information chip. From there followed universal libraries and museums, connecting his native Belgium to the world by means of a vast intellectual enterprise that attempted to organize and code everything ever published. Forty years before the first personal computer and fifty years before the first browser, Otlet envisioned a network of “electric telescopes” that would allow people everywhere to search through books, newspapers, photographs, and recordings, all linked together in what he termed, in 1934, a reseau mondial—essentially, a worldwide web.

James Somers says that we’re probably using the wrong dictionary and that most modern dictionaries are “where all the words live and the writing’s no good”.

The New Oxford American dictionary, by the way, is not like singularly bad. Google’s dictionary, the modern Merriam-Webster, the dictionary at dictionary.com: they’re all like this. They’re all a chore to read. There’s no play, no delight in the language. The definitions are these desiccated little husks of technocratic meaningese, as if a word were no more than its coordinates in semantic space.

As a counterpoint, Somers offers John McPhee’s secret weapon, Webster’s Revised Unabridged Dictionary, the bulk of which was the work of one man and was last revised in 1913.

Take a simple word, like “flash.” In all the dictionaries I’ve ever known, I would have never looked up that word. I’d’ve had no reason to — I already knew what it meant. But go look up “flash” in Webster’s (the edition I’m using is the 1913). The first thing you’ll notice is that the example sentences don’t sound like they came out of a DMV training manual (“the lights started flashing”) — they come from Milton and Shakespeare and Tennyson (“A thought flashed through me, which I clothed in act”).

You’ll find a sense of the word that is somehow more evocative than any you’ve seen. “2. To convey as by a flash… as, to flash a message along the wires; to flash conviction on the mind.” In the juxtaposition of those two examples — a message transmitted by wires; a feeling that comes suddenly to mind — is a beautiful analogy, worth dwelling on, and savoring. Listen to that phrase: “to flash conviction on the mind.” This is in a dictionary, for God’s sake.

And, toward the bottom of the entry, as McPhee promised, is a usage note, explaining the fine differences in meaning between words in the penumbra of “flash”:

“… Flashing differs from exploding or disploding in not being accompanied with a loud report. To glisten, or glister, is to shine with a soft and fitful luster, as eyes suffused with tears, or flowers wet with dew.”

Did you see that last clause? “To shine with a soft and fitful luster, as eyes suffused with tears, or flowers wet with dew.” I’m not sure why you won’t find writing like that in dictionaries these days, but you won’t. Here is the modern equivalent of that sentence in the latest edition of the Merriam-Webster: “glisten applies to the soft sparkle from a wet or oily surface .”

Who decided that the American public couldn’t handle “a soft and fitful luster”? I can’t help but think something has been lost. “A soft sparkle from a wet or oily surface” doesn’t just sound worse, it actually describes the phenomenon with less precision. In particular it misses the shimmeriness, the micro movement and action, “the fitful luster,” of, for example, an eye full of tears — which is by the way far more intense and interesting an image than “a wet sidewalk.”

It’s as if someone decided that dictionaries these days had to sound like they were written by a Xerox machine, not a person, certainly not a person with a poet’s ear, a man capable of high and mighty English, who set out to write the secular American equivalent of the King James Bible and pulled it off.

Don’t miss the end of the piece, where Somers shows how to replace the tin-eared dictionaries on your Mac, iPhone, and Kindle with the Webster’s 1913. (via @satishev)

Update: In the same vein, Kevin Kelly recommends using The Synonym Finder as a thesaurus.

Just look up a word, any word, and it proceeds to overwhelm you with alternative choices (a total of 1.5 million synonyms are presented in 1,361 pages), including short phrases and only mildly related words. Rather than being a problem of imprecision, the Finder’s broad inclusiveness prods your imagination and prompts your recall.

What if Ayn Rand had written Harry Potter? It might go a little something like this.

Professor Snape stood at the front of the room, sort of Jewishly. “There will be no foolish wand-waving or silly incantations in this class. As such, I don’t expect many of you to appreciate the subtle science and exact art that is potion-making. However, for those select few who possess, the predisposition…I can teach you how to bewitch the mind and ensnare the senses. I can tell you how to bottle fame, brew glory, and even put a stopper in death.”

Harry’s hand shot up.

“What is it, Potter?” Snape asked, irritated.

“What’s the value of these potions on the open market?”

“What?”

“Why are you teaching children how to make these valuable products for ourselves at a schoolteacher’s salary instead of creating products to meet modern demand?”

“You impertinent boy-“

“Conversely, what’s to stop me from selling these potions myself after you teach us how to master them?”

“I-“

“This is really more of a question for the Economics of Potion-Making, I guess. What time are econ lessons here?”

“We have no economics lessons in this school, you ridiculous boy.”

Harry Potter stood up bravely. “We do now. Come with me if you want to learn about market forces!”

The students poured into the hallway after him. They had a leader at last.

Steven Johnson has been working on a six-part series for PBS called How We Got to Now. (There’s a companion book as well.) The series is due in October but the trailer dropped today:

And here’s a snippet of one of the episodes about railway time. I’m quite looking forward to this series; Johnson and I cover similar ground in our work with similar sensibilities. I’m always cribbing stuff from his writing and using his frameworks to think things through and just from the trailer, I counted at least three things I’ve covered on kottke.org in the past: Hedy Lamarr, urban sanitation, and Jacbo Riis (not to mention all sorts of stuff about time).

From a book by Hartmut Esslinger, a collection of photographs of prototypes his company Frog Design worked on for Apple Computer.

The portables and phones are especially interesting.

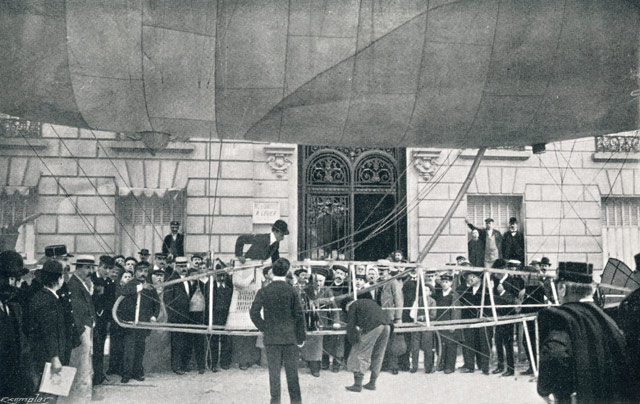

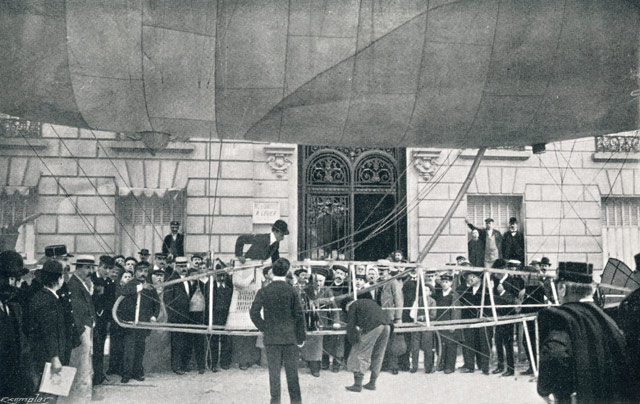

In Brazil’s National Air and Space Museum, there is a golden globe containing the preserved heart of Alberto Santos-Dumont, a man who thought he beat the Wright Brothers in building and flying the first heavier-than-air flying machine. Santos-Dumont’s first success was with dirigibles; at the turn of the century, he would regularly use his personal airship to fly to dinner or to visit friends.

Imagine the frenetic pace of life in belle époque Paris. Automobiles appearing on the streets, attracting huge crowds. The telegraph bringing news from all over the world. Cafés playing phonographs while their patrons drank absinthe and cocaine wine. Now imagine a Parisian walking the streets in the early morning, in a time where an automobile was still a fascinating novelty, and then suddenly, a small airship appears floating just above the street. A crowd would gather to see the aviator driving his Baladeuse (The Wanderer), a personal sized dirigible, over the streets as if it were a carriage or automobile. Santos-Dumont would then land in front of his favorite café, tie the guide rope much like one might tie a horse to a hitching post, and walk in for a meal. It must have been quite a sight. Going to the café was not the only time Santos-Dumont used his Baladeuse — he was also fond of surprising his friends by landing in front of their porches with his airship.

Paul Hoffman wrote a well-reviewed book about Santos-Dumont called Wings of Madness.

Let’s talk cultural mesofacts. You likely recall 50 Cent as a rapper In Da Club but much has happened since then. 50 diversified like crazy: started a record label, parlayed a possible Vitaminwater endorsement into an investment worth $100 million, and, relevant to the matter at hand, wrote several books, including a pair of self-improvement books: Formula 50: A 6-Week Workout and Nutrition Plan That Will Transform Your Life and The 50th Law. Zach Baron recently recruited 50 Cent to be his life coach for a GQ piece and it ends up going way better than he expected.

50 Cent thinks for a minute. Actually, he says, my girlfriend — the one I just mentioned, the one I’d just moved in with? 50 Cent would like her to make a vision board, too. Then we’re going to compare. “Take things out of your folder and things out of her folder to create a folder that has everything,” he says. “Now the vision board is no longer your personal vision board for yourself: It’s a joint board.” That joint board will represent what we have in common. It will be a monument to our love.

But there will be some leftover unmatched photos, too, in each of our folders. And that’s what the joint board is really for — what it’s designed to reveal. “The things that end up on your vision board that aren’t in hers are the things that she has to accept,” 50 Cent says. “And the things that she has that you don’t are the things that you have to make a compromise with.” In a healthy relationship, he explains, your differences are really what need talking about. This is how you go about making that conversation happen.

This article just keeps getting better the more you read it. (via @ystrickler)

Internet mega-retailer Amazon is trying, mob-style, to pressure Hachette for better terms on ebooks by disappearing the publisher’s book from amazon.com.

The retailer began refusing orders late Thursday for coming Hachette books, including J.K. Rowling’s new novel. The paperback edition of Brad Stone’s “The Everything Store: Jeff Bezos and the Age of Amazon” — a book Amazon disliked so much it denounced it — is suddenly listed as “unavailable.”

In some cases, even the pages promoting the books have disappeared. Anne Rivers Siddons’s new novel, “The Girls of August,” coming in July, no longer has a page for the physical book or even the Kindle edition. Only the audio edition is still being sold (for more than $60). Otherwise it is as if it did not exist.

No question about it: this sucks on Amazon’s part and demonstrates the degree to which the company’s top priority isn’t customer service. Better customer service in this case would be to offer these books for sale. I noticed another less nefarious instance of this the other day: because Amazon is offering a streaming version of The Lego Movie (which presumably has a high profit margin), they are not currently taking pre-orders of the The Lego Movie Blu-ray (out on June 17), even though Barnes and Noble has it for pre-order and Amazon has no problem offering for pre-order a Blu-ray of The Nutty Professor that isn’t out until September. I guess it makes sense to drive sales to the high-margin streaming offering but not letting people pre-order what is likely to be a very popular Blu-ray is baffling.

Anyway, if this trend continues, I’d look for Amazon to start more aggressively promoting the Kindle editions of books, to the point of manipulating available inventory as with Hachette. That is, if they’re not doing it already.

Newer posts

Older posts

Stay Connected