kottke.org posts about books

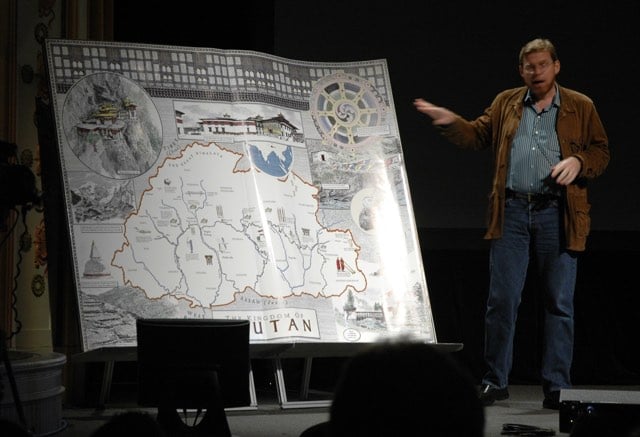

When I went to the Poptech conference 10 years ago, one of the talks featured one of the world’s largest books, a book of photographs of Bhutan. The book used to fetch $10,000 a copy, but Amazon now sells it for just under $300. Something is fishy though…many of the vendors selling the book are shipping it for only $3.99, which seems unlikely for a book that weighs 133 pounds. (via cory)

Update: Long story short, there were two versions of this book made: the big one and a smaller one that’s only a foot and a half tall. That Amazon link used to go to the big book but it’s the little one now. Make sense? Anyway, here’s a link to the big one if you want to buy it for $5,824.34 with free shipping. (thx everyone)

Kazuo Ishiguro wrote his excellent novel, The Remains of the Day, in only four weeks (more or less).

So Lorna and I came up with a plan. I would, for a four-week period, ruthlessly clear my diary and go on what we somewhat mysteriously called a “Crash”. During the Crash, I would do nothing but write from 9am to 10.30pm, Monday through Saturday. I’d get one hour off for lunch and two for dinner. I’d not see, let alone answer, any mail, and would not go near the phone. No one would come to the house. Lorna, despite her own busy schedule, would for this period do my share of the cooking and housework. In this way, so we hoped, I’d not only complete more work quantitively, but reach a mental state in which my fictional world was more real to me than the actual one.

If you’ve read The Hobbit and the Lord of the Rings trilogy (and/or watched the movies1) but didn’t delve into the appendices or, shudder, The Silmarillion, this is the video for you. It explains about the Gods who created Middle Earth, what wizards are (not men, but angels), and the specialness of Men and Elves.

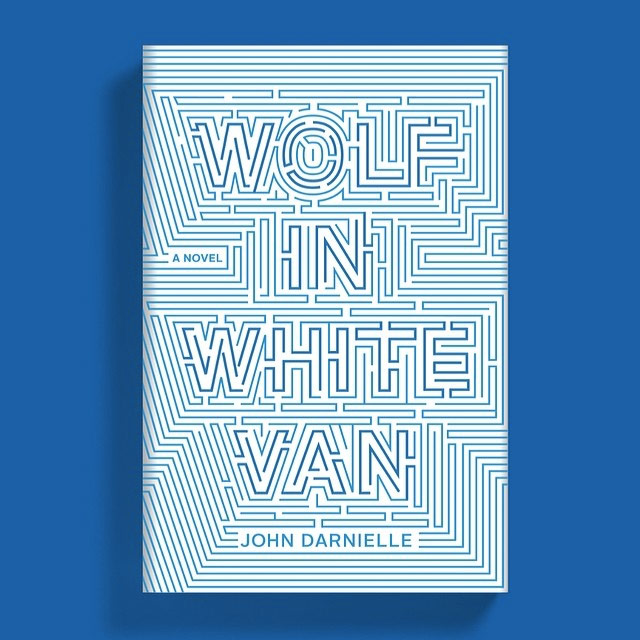

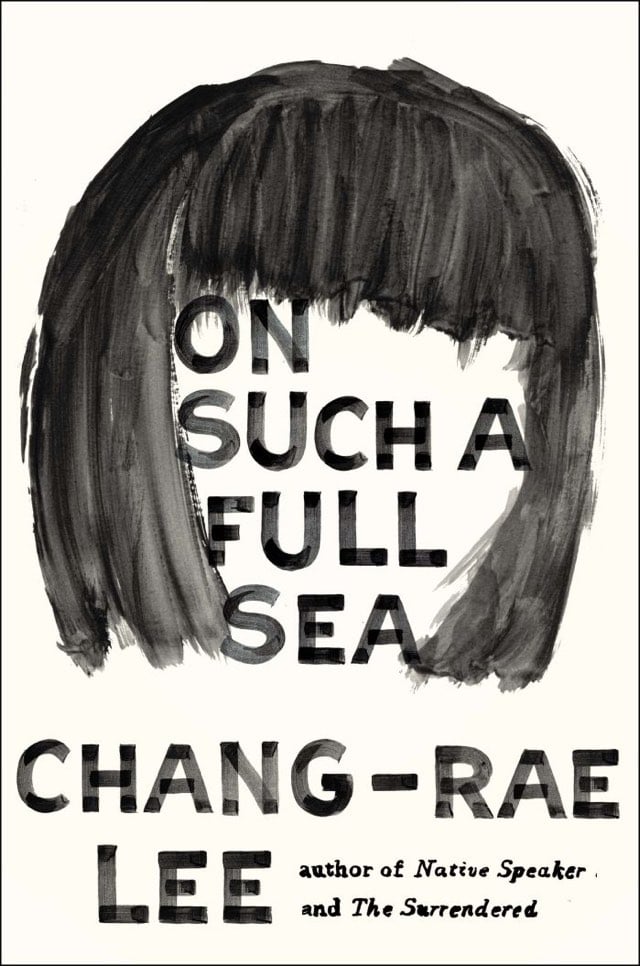

At the NY Times, Nicholas Blechman weighs in with his picks for the best book covers of 2014.

Dan Wagstaff, aka The Casual Optimist, picked 50 Covers for 2014.

From Jarry Lee at Buzzfeed, 32 Of The Most Beautiful Book Covers Of 2014.

Paste’s Liz Shinn and Alisan Lemay present their 30 Best Book Covers of 2014.

And from much earlier in the year (for some reason), Zachary Petit’s 19 of the Best Book Covers of 2014 at Print.

Wait, how did I miss this…Hilary Mantel’s excellent pair of novels about Thomas Cromwell & Henry VIII, Wolf Hall and Bring Up the Bodies, are being turned into a six-part BBC miniseries. Outstanding! Noted Shakespearian actor Mark Rylance will play Cromwell with Homeland’s Damian Lewis as Henry VIII.

BBC One will be airing the show in Britain in January while American audiences without access to BitTorrent will have to wait until PBS airs it in April.

Wow, the art of making marbled paper, a short film from 1970. Charmingly British, just like the film about the Teddy Grays candy factory or the putter togetherer of scissors. Super cool how the inks are placed on a water bath, swirled expertly to make patterns, and then transferred to the paper.

Also of note: the segment on the conservation of old books starting at around 9:55…I never knew they took them apart like that to dunk the pages in water! Sadly, the Cockerell Bindery ceased operation in the late 1980s with the death of Sydney Cockerell and its contents were sold at auction. (thx, matt)

Photographer Noah Kalina (of Everyday fame) keeps a blog of his purchases from Amazon called Amazon Primed. Recently documented purchases include a Weber grill and a shoulder mount for a camera. Now Kalina has turned his blog into a book published by Amazon.

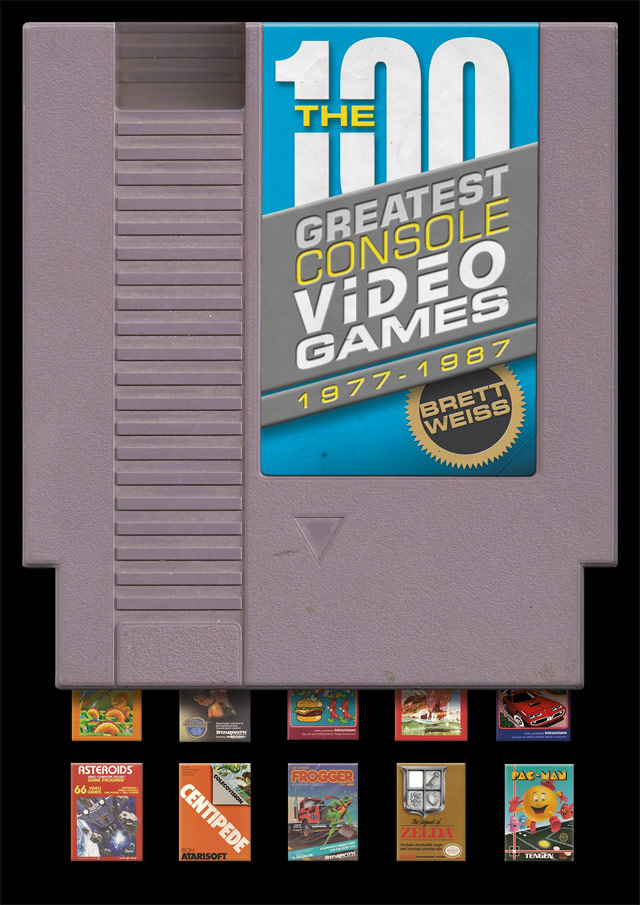

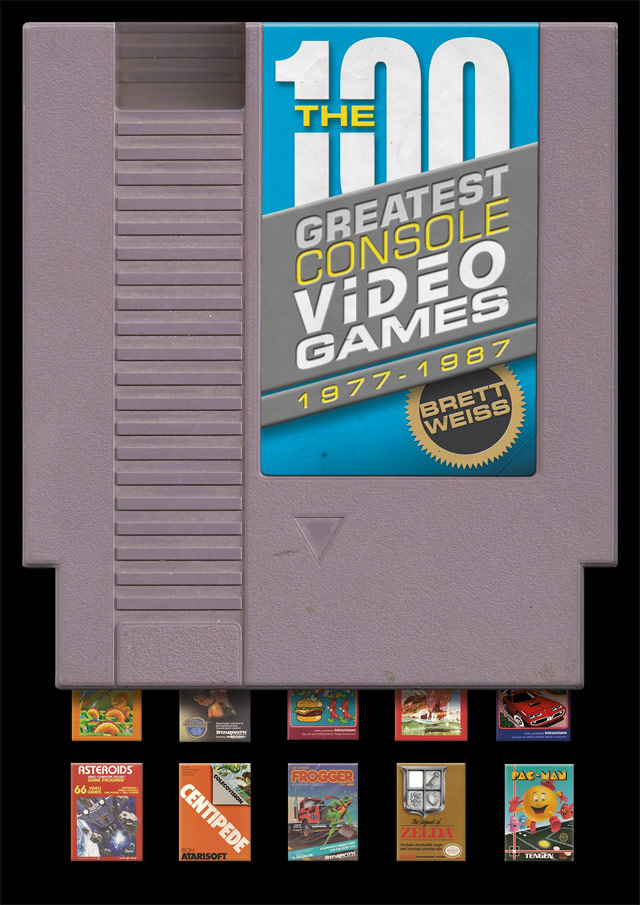

The 100 Greatest Console Video Games: 1977-1987 is a recent book chronicling the best games from the first golden era in console video games, from the Intellivision1 to the Atari 2600 to the Nintendo.

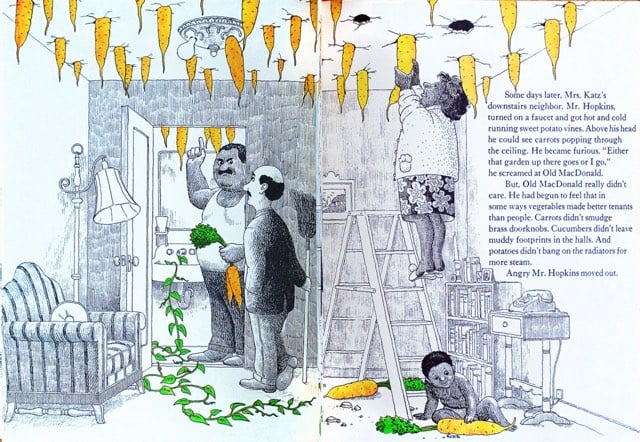

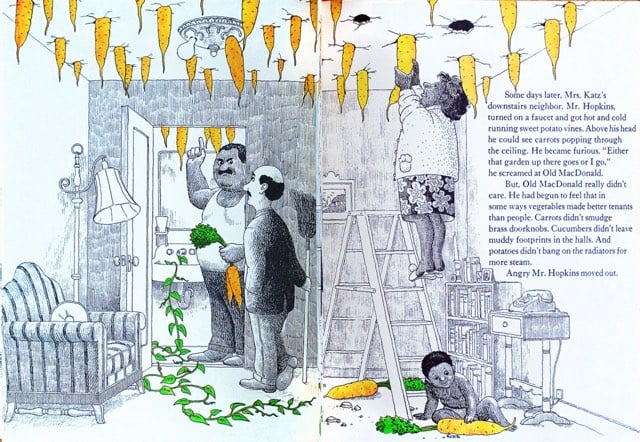

My favorite book when I was a kid was Cloudy With a Chance of Meatballs by Judi and Ronald Barrett.1 So I was excited when the kids brought home a book from the library from the same authors that I hadn’t seen before: Old MacDonald Had An Apartment House. The story is about an apartment building super who starts growing food and raising livestock in vacant apartments as the increasingly alarmed tenants move out. Totally awesome 70s hippie energy crisis stuff. It didn’t click that I had actually read (and loved!) this book as a kid until we reached this page:

Love that page. Hot and cold running sweet potato vines.

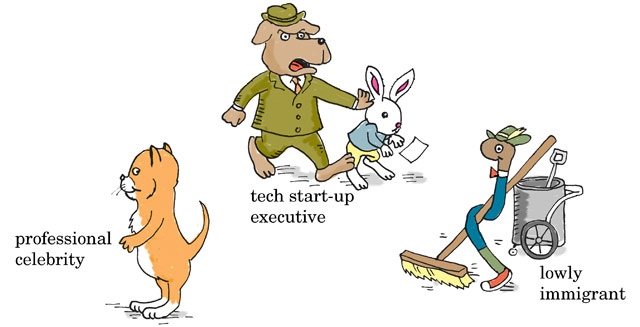

Oh, this is great. The butchers, farmers, doctors, and children’s book librarians of Richard Scarry’s original Busy, Busy Town give way to the non-lending officer, one-percenter service provider, fart-sound app maker, and lowly immigrant in Tom the Dancing Bug’s 21st century Busy Town.

For his recently released book Wild Life, Brad Wilson shot photos of all kinds of animals on a black background, resulting in unusually expressive portraits.

Reminds me of Jill Greenberg’s monkey portraits…expressive in the same way.

Lauren Ipsum is a book about computer science for kids (age 10 and up) published by No Starch Press.

Meet Lauren, an adventurer who knows all about solving problems. But she’s lost in the fantastical world of Userland, where mail is delivered by daemons and packs of wild jargon roam.

Lauren sets out for home, traveling through a journey of puzzles, from the Push and Pop Cafe to the Garden of the Forking Paths. As she discovers the secrets of Userland, Lauren learns about computer science without even realizing it-and so do you!

Sounds intriguing. And 1000 bonus points for making the protagonist a girl. There’s an older self-published version of the book that’s been out for a couple of years. I like the older description slightly better:

Laurie is lost in Userland. She knows where she is, or where she’s going, but maybe not at the same time. The only way out is through Jargon-infested swamps, gates guarded by perfect logic, and the perils of breakfast time at the Philosopher’s Diner. With just her wits and the help of a lizard who thinks he’s a dinosaur, Laurie has to find her own way home.

Lauren Ipsum is a children’s story about computer science. In 20 chapters she encounters dozens of ideas from timing attacks to algorithm design, the subtle power of names, and how to get a fair flip out of even the most unfair coin.

Has anyone read it?

In his recent book, How Star Wars Conquered the Universe, Chris Taylor tells the story of how avant garde cinema fan George Lucas built one of the biggest movie franchises ever.

How did a few notes scribbled on a legal pad in 1973 by George Lucas, a man who hated writing, turn into a four billion dollar franchise that has quite literally transformed the way we think about entertainment, merchandizing, politics, and even religion? A cultural touchstone and cinematic classic, Star Wars has a cosmic appeal that no other movie franchise has been able to replicate. From Jedi-themed weddings and international storm-trooper legions, to impassioned debates over the digitization of the three Star Wars prequels, to the shockwaves that continue to reverberate from Disney’s purchase of the beloved franchise in 2012, the series hasn’t stopped inspiring and inciting viewers for almost forty years. Yet surprisingly little is known about its history, its impact — or where it’s headed next.

(via mr)

Near the end of Lolita, Vladimir Nabokov writes:

Had I done to Dolly, perhaps, what Frank Lasalle, a fifty-year-old mechanic, had done to eleven-year-old Sally Horner in 1948?

For years, no one picked up on the fact that Sally Horner really was abducted by a man named Frank La Salle in 1948 and the crime was a definite influence on Nabokov in writing Lolita, not until Alexander Dolinin suggested it in 2005. Sarah Weinman explores the connection in Hazlitt.

On her way home from school the next day, though, the man sought her out again. Without warning, the rules had changed: Sally had to go with him to Atlantic City — the government insisted. She’d have to convince her mother he was the father of two school friends, inviting her to a seashore vacation. He would take care of the rest with a phone call and a convincing appearance at the Camden bus depot.

His name was Frank La Salle, and he was no FBI agent — rather, he was the sort G-men wanted to drive off the streets, though Sally didn’t learn that until it was far too late. It took 21 months to break free of him, after a cross-country journey from Camden, New Jersey, to San Jose, California. That five-cent notebook didn’t just alter Sally Horner’s own life, though: it reverberated throughout the culture, and in the process, irrevocably changed the course of 20th-century literature.

(via @DavidGrann)

The Marshmallow Test was developed by psychologist Walter Mischel to study self-control and delayed gratification. From a piece about Mischel in the New Yorker:

Once Mischel began analyzing the results, he noticed that low delayers, the children who rang the bell quickly, seemed more likely to have behavioral problems, both in school and at home. They got lower S.A.T. scores. They struggled in stressful situations, often had trouble paying attention, and found it difficult to maintain friendships. The child who could wait fifteen minutes had an S.A.T. score that was, on average, two hundred and ten points higher than that of the kid who could wait only thirty seconds.

Mischel has written a book about the test, its findings, and learning greater self-control: The Marshmallow Test: Mastering Self-Control.

The world’s leading expert on self-control, Walter Mischel has proven that the ability to delay gratification is critical for a successful life, predicting higher SAT scores, better social and cognitive functioning, a healthier lifestyle and a greater sense of self-worth. But is willpower prewired, or can it be taught?

In The Marshmallow Test, Mischel explains how self-control can be mastered and applied to challenges in everyday life — from weight control to quitting smoking, overcoming heartbreak, making major decisions, and planning for retirement. With profound implications for the choices we make in parenting, education, public policy and self-care, The Marshmallow Test will change the way you think about who we are and what we can be.

Here’s a video of the test in action:

Update: A recent study showed that the environment in which the test is performed is important.

Now a new study demonstrates that being able to delay gratification is influenced as much by the environment as by innate ability. Children who experienced reliable interactions immediately before the marshmallow task waited on average four times longer — 12 versus three minutes — than youngsters in similar but unreliable situations.

(thx, maggie & adam)

Acclaimed science and math writer Simon Singh has written a book on the mathematics of The Simpsons, The Simpsons and Their Mathematical Secrets. Boing Boing has an excerpt.

The principles of rubber sheet geometry can be extended into three dimensions, which explains the quip that a topologist is someone who cannot tell the difference between a doughnut and a coffee cup. In other words, a coffee cup has just one hole, created by the handle, and a doughnut has just one hole, in its middle. Hence, a coffee cup made of a rubbery clay could be stretched and twisted into the shape of a doughnut. This makes them homeomorphic.

By contrast, a doughnut cannot be transformed into a sphere, because a sphere lacks any holes, and no amount of stretching, squeezing, and twisting can remove the hole that is integral to a doughnut. Indeed, it is a proven mathematical theorem that a doughnut is topologically distinct from a sphere. Nevertheless, Homer’s blackboard scribbling seems to achieve the impossible, because the diagrams show the successful transformation of a doughnut into a sphere. How?

Although cutting is forbidden in topology, Homer has decided that nibbling and biting are acceptable. After all, the initial object is a doughnut, so who could resist nibbling? Taking enough nibbles out of the doughnut turns it into a banana shape, which can then be reshaped into a sphere by standard stretching, squeezing, and twisting. Mainstream topologists might not be thrilled to see one of their cherished theorems going up in smoke, but a doughnut and a sphere are identical according to Homer’s personal rules of topology. Perhaps the correct term is not homeomorphic, but rather Homermorphic.

Changing your mind about something significant as an adult can be very difficult. For many, ideas are identity, and the particular set of ideas you currently possess got you where you are today, so why switch it up? The Chronicle Review recently asked a group of scholars which non-fiction book “profoundly altered the way they regard themselves, their work, the world”. Law professor William Ian Miller had this to say:

No nonfiction books in the past 30 years have transformed me. Some have taught me things, made me hold their authors in deep respect (Bartlett, Bynum). Some have moved me greatly (some of the better soldier memoirs). But knocked me off my horse on the way to Damascus? Nope.

I am 68; if you had asked me the question about a self-transforming book when I was 19, I would have had to say just about half of the ones I read. You could say these books changed my mind, but my mind was pretty much a tabula rasa when I was in my first year of college. Rather they made my mind.

The David Foster Wallace Reader is a collection of Wallace’s best, funniest, and most celebrated writing.

Where do you begin with a writer as original and brilliant as David Foster Wallace? Here — with a carefully considered selection of his extraordinary body of work, chosen by a range of great writers, critics, and those who worked with him most closely. This volume presents his most dazzling, funniest, and most heartbreaking work — essays like his famous cruise-ship piece, “A Supposedly Fun Thing I’ll Never Do Again,” excerpts from his novels The Broom of the System, Infinite Jest, and The Pale King, and legendary stories like “The Depressed Person.”

Wallace’s explorations of morality, self-consciousness, addiction, sports, love, and the many other subjects that occupied him are represented here in both fiction and nonfiction. Collected for the first time are Wallace’s first published story, “The View from Planet Trillaphon as Seen In Relation to the Bad Thing” and a selection of his work as a writing instructor, including reading lists, grammar guides, and general guidelines for his students.

If you’ve somehow been waiting to dig into Wallace’s writing but didn’t know where to start, this is where you start.

Kip Thorne is a theoretical physicist who did some of the first serious work on the possibility of travel through wormholes. Several years ago, he resigned as the Feynman Professor of Theoretical Physics from Caltech in part to make movies. To that end, Thorne acted as Christopher Nolan’s science advisor for Interstellar. As a companion to the movie, Thorne wrote a book called The Science of Interstellar.

Yet in The Science of Interstellar, Kip Thorne, the physicist who assisted Nolan on the scientific aspects of Interstellar, shows us that the movie’s jaw-dropping events and stunning, never-before-attempted visuals are grounded in real science. Thorne shares his experiences working as the science adviser on the film and then moves on to the science itself. In chapters on wormholes, black holes, interstellar travel, and much more, Thorne’s scientific insights — many of them triggered during the actual scripting and shooting of Interstellar — describe the physical laws that govern our universe and the truly astounding phenomena that those laws make possible.

Wired has a piece on how Thorne and Nolan worked together on the film. Phil Plait was unimpressed with some of the science in the movie, although he retracted some of his criticism. If you’re confused by the science or plot, Slate has a FAQ.

Update: Well, well, the internet’s resident Science Movie Curmudgeon Neil deGrasse Tyson actually liked the depiction of science in Interstellar. In particular: “Of the leading characters (all of whom are scientists or engineers) half are women. Just an FYI.” (via @thoughtbrain)

Update: What’s wrong with “What’s Wrong with the Science of Movies About Science?” pieces? Plenty says Matt Singer.

But a movie is not its marketing; regardless of what ‘Interstellar”s marketing said, the film itself makes no such assertions about its scientific accuracy. It doesn’t open with a disclaimer informing viewers that it’s based on true science; in fact, it doesn’t open with any sort of disclaimer at all. Nolan never tells us exactly where or when ‘Interstellar’ is set. It seems like the movie takes place on our Earth in the relatively near future, but that’s just a guess. Maybe ‘Interstellar’ is set a million years after our current civilization ended. Or maybe it’s set in an alternate dimension, where the rules of physics as Phil Plait knows them don’t strictly apply.

Or maybe ‘Interstellar’ really is set on our Earth 50 years in the future, and it doesn’t matter anyway because ‘Interstellar’ is a work of fiction. It’s particularly strange to see people holding ‘Interstellar’ up to a high standard of scientific accuracy because the movie is pretty clearly a work of stylized, speculative sci-fi right from the start.

(via @khoi)

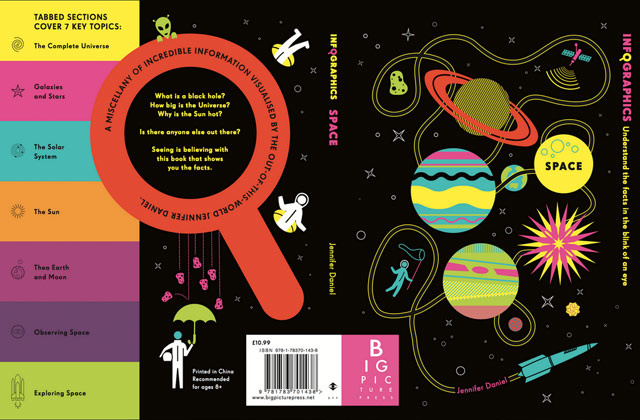

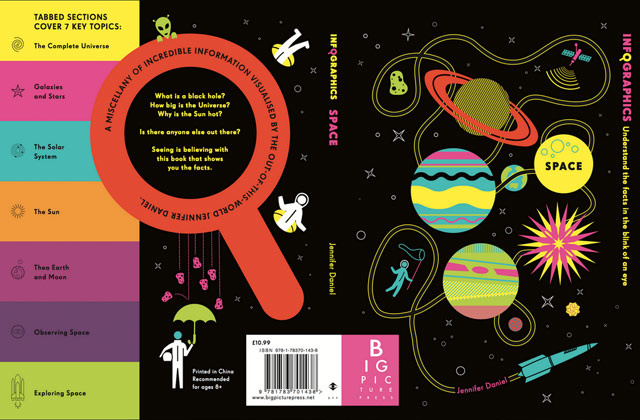

A children’s book about space featuring information graphics illustrated by the completely awesome Jennifer Daniel!?

The third in a visually stunning series of information graphics that shows just how interesting and humorous scientific information can be. Complex facts about space are reinterpreted as stylish infographics that astonish, amuse, and inform.

INSTANT PURCHASE. February 2015 cannot come fast enough.

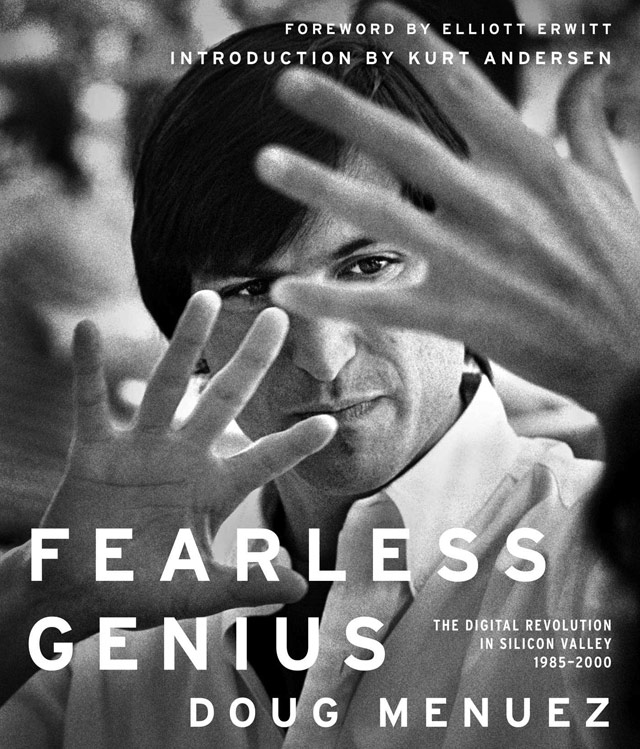

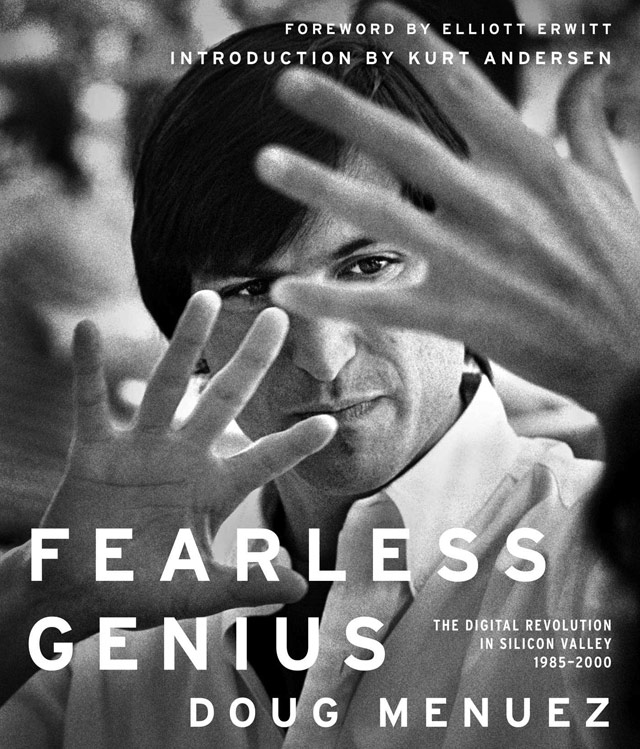

Beginning in 1985, photographer and filmmaker Doug Menuez wrangled access to some of the people at the center of the Silicon Valley technology boom, including Steve Jobs as he broke away from Apple to create NeXT. Menuez has published more than 100 of those behind-the-scenes photos in a new book, Fearless Genius.

In the spring of 1985, a technological revolution was under way in Silicon Valley, and documentary photographer Doug Menuez was there in search of a story — something big. At the same time, Steve Jobs was being forced out of his beloved Apple and starting over with a new company, NeXT Computer. His goal was to build a supercomputer with the power to transform education. Menuez had found his story: he proposed to photograph Jobs and his extraordinary team as they built this new computer, from conception to product launch.

In an amazing act of trust, Jobs granted Menuez unlimited access to the company, and, for the next three years, Menuez was able to get on film the spirit and substance of innovation through the day-to-day actions of the world’s top technology guru.

The web site for the project details some of the other things Menuez has in store, including a feature-length documentary and a TV series. Ambitious. For a sneak peek, check out the NeXT-era photos Menuez posted at Storehouse. This image of Jobs, labelled “Steve Jobs Pretending to Be Human”, is a particular favorite:

(via df)

From the emergence of markets in the 13th century to the scientific revolution of the 17th century to castles in the 11th century, this is a list of historian Ian Mortimer’s 10 biggest changes of the past 1000 years.

Most people think of castles as representative of conflict. However, they should be seen as bastions of peace as much as war. In 1000 there were very few castles in Europe — and none in England. This absence of local defences meant that lands were relatively easy to conquer — William the Conqueror’s invasion of England was greatly assisted by the lack of castles here. Over the 11th century, all across Europe, lords built defensive structures to defend them and their land. It thus became much harder for kings to simply conquer their neighbours. In this way, lords tightened their grip on their estates, and their masters started to think of themselves as kings of territories, not of tribes. Political leaders were thus bound to defend their borders — and govern everyone within those borders, not just their own people. That’s a pretty enormous change by anyone’s standards.

The list is adapted from Mortimer’s recent book, Centuries of Change.

Canadian astronaut Chris Hadfield became a celebrity while aboard the International Space Station. Now he’s publishing a book of photographs he took during his time in orbit: You Are Here: Around the World in 92 Minutes.

During 2,597 orbits of our planet, I took about 45,000 photographs. At first, my approach was scattershot: just take as many pictures as possible. As time went on, though, I began to think of myself as a hunter, silently stalking certain shots. Some eluded me: Brasilia, the capital of Brazil, and Uluru, or Ayers Rock, in Australia. I captured others only after methodical planning: “Today, the skies are supposed to be clear in Jeddah and we’ll be passing nearby in the late afternoon, so the angle of the sun will be good. I need to get a long lens and be waiting at the window, looking in the right direction, at 4:02 because I’ll have less than a minute to get the shot.” Traveling at 17,500 miles per hour, the margin for error is very slim. Miss your opportunity and it may not arise again for another six weeks, depending on the ISS’s orbital path and conditions on the ground.

In an interview with Quartz, Hadfield says the proceeds from the book are being donated to the Red Cross.

The NY Times interviewed several people in their 80s who are still killing it in their careers and creative pursuits. Says Ruth Bader Ginsberg about surprises about turning 80:

Nothing surprised me. But I’ve learned two things. One is to seek ever more the joys of being alive, because who knows how much longer I will be living? At my age, one must take things day by day. I have been asked again and again, “How long are you going to stay there?” I make that decision year by year. The minute I sense I am beginning to slip, I will go. There’s a sense that time is precious and you should enjoy and thrive in what you’re doing to the hilt. I appreciate that I have had as long as I have… It’s a sense reminiscent of the poem “Gather ye rosebuds while ye may.” I had some trying times when my husband died. We’d been married for 56 years and knew each other for 60. Now, four years later, I’m doing what I think he would have wanted me to do.

The interviews are accompanied by an essay by Lewis Lapham, himself on the cusp of 80.

John D. Rockefeller in his 80s was known to his business associates as a crazy old man possessed by the stubborn and ferocious will to know why the world wags and what wags it, less interested in money than in the solving of a problem in geography or corporate combination. By sources reliably informed I’m told that Warren Buffett, 84, and Rupert Murdoch, 83, never quit asking questions.

I read a book several years ago which is relevant here called Old Masters and Young Geniuses, in which economist David Galenson divided creative people into two main camps: conceptual and experimental innovators:

1) The conceptual innovators who peak creatively early in life. They have firm ideas about what they want to accomplish and then do so, with certainty. Pablo Picasso is the archetype here; others include T.S. Eliot, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and Orson Wells. Picasso said, “I don’t seek, I find.”

2) The experimental innovators who peak later in life. They create through the painstaking process of doing, making incremental improvements to their art until they’re capable of real masterpiece. Cezanne is Galenson’s main example of an experimental innovator; others include Frank Lloyd Wright, Mark Twain, and Jackson Pollock. Cezanne remarked, “I seek in painting.”

As Ebola enters a deepening relationship with the human species, the question of how it is mutating has significance for every person on earth.

From the front lines in West Africa to the genomics researchers who hope to control the outbreak, The New Yorker’s Richard Preston provides a detailed and interesting look at The Ebola Wars. Preston is the author of 1995’s The Hot Zone, the bestselling account of the first emergence of Ebola, which is back in the top 50 on Amazon.

From Silence of the Lambs (#1) to To Kill A Mocking Bird (#9) to Blade Runner (#28), these are the 50 best book-to-movie adaptations ever, compiled by Total Film.

Somehow absent is Spike Jonze’s Adaptation and I guess 2001 was not technically based on a book, but whatevs. The commenters additionally lament the lack of Requiem for a Dream, Gone with the Wind, The French Connection, Rosemary’s Baby, Last of the Mohicans, and The Wizard of Oz.

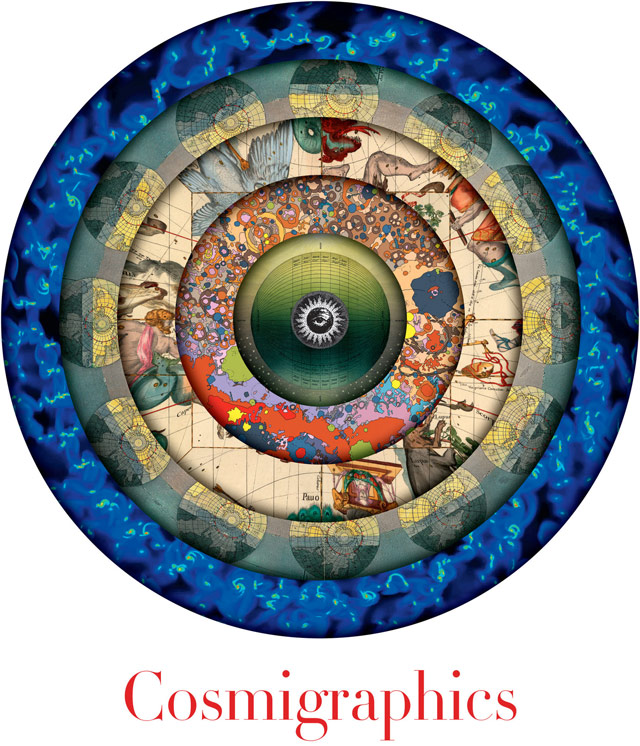

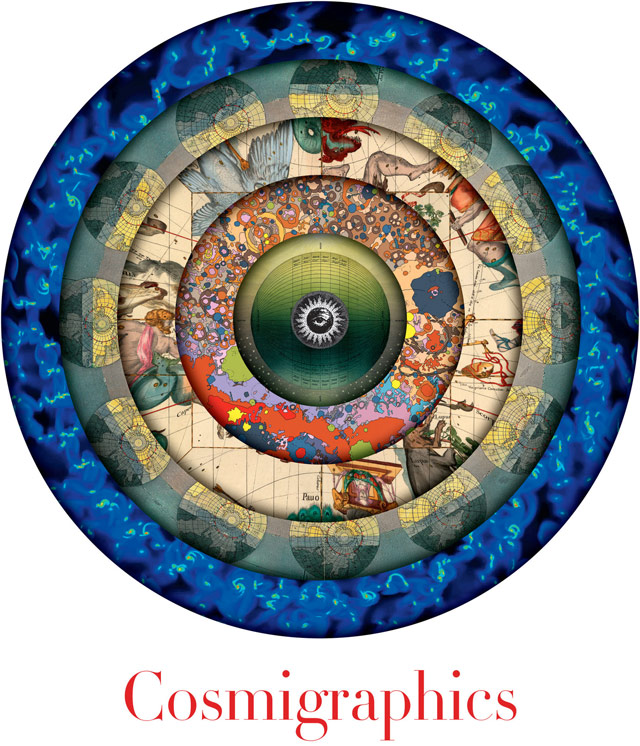

From Michael Benson comes Cosmigraphics, a survey of many ways in which humans have represented the Universe, from antiquity on up to the present day.

Selecting artful and profound illustrations and maps, many hidden away in the world’s great science libraries and virtually unknown today, he chronicles more than 1,000 years of humanity’s ever-expanding understanding of the size and shape of space itself. He shows how the invention of the telescope inspired visions of unimaginably distant places and explains why today we turn to supercomputer simulations to reveal deeper truths about space-time.

The NY Times has an adaptation of the introduction to the book.

Among the narrative threads woven into the book are the 18th-century visual meditations on the possible design of the Milky Way - including the astonishing work of the undeservedly obscure English astronomer Thomas Wright, who in 1750 reasoned his way to (and illustrated) the flattened-disk form of our galaxy. In a book stuffed with exquisite mezzotint plates, Wright also conceived of another revolutionary concept: a multigalaxy cosmos. All of this a quarter-century before the American Revolution, at a time when the Milky Way was thought to constitute the entirety of the universe.

Speaking of PBS shows, Steven Johnson’s How We Got to Now starts on PBS tonight with two back-to-back episodes. The NY Times has a positive review.

The opening episode, for instance, is called “Clean,” and it sets the pattern for the five that follow. We tend not to acknowledge just how recent some of the trends and comforts of modern life are, including the luxury of not walking through horse manure and human waste on the way to the post office.

The episode turns back the clock just a century and a half, to a time before our liquid waste stream was largely contained in underground pipes. Mr. Johnson then traces the emergence of the idea that with a little effort, cities and towns could have a cleaner existence, and the concurrent idea that cleanliness would have public health benefits.

But his examination of “the ultraclean revolution,” as he calls it, doesn’t stop at the construction of sewage and water-purification systems. He extends the thread all the way to the computer revolution, visiting a laboratory where microchips are made.

The show is based on Johnson’s book of the same name, which enters the NY Times bestseller list at #4 this week. Also, I keep wanting to call the book/show How We Got to Know, which strikes me as a perfectly appropriate title as well.

Update: The first two episodes are available online until 10/30.

Update: How We Got to Now is now available on Netflix and Amazon Prime Video.

Atul Gawande’s best selling Being Mortal is getting the Frontline treatment on PBS this January. Here’s the trailer:

In the November issue of Elle, Laurie Abraham talks about the fear, pressure, regret, and misconceptions related to how we think about abortion in America, written through the lens of her own experiences.

In several meetings at work in which this essay was discussed, I noticed that none of the other editors in the room, all of them pro-choice, could bring themselves to utter the word abortion; it was “Laurie’s pro piece,” or her “memoir.” I know that my colleagues, many of whom are my friends, were just trying to be kind when they referred to my “reproductive rights” story. The truth is, I felt uncomfortable saying it out loud too. Abortion is a conversational third rail, women’s dirtiest dirty laundry, to mix metaphors. Because the other thing about living in a political culture where a single-cell zygote is constantly being called a “person” is that there is a penumbra of shame surrounding abortion. For myself, however, I wonder: Am I really ashamed — and, if so, what is it exactly that I’m ashamed of?

The book Abraham references throughout, Katha Pollitt’s Pro: Reclaiming Abortion Rights sounds really interesting. (via @atotalmonet)

Newer posts

Older posts

Stay Connected