kottke.org posts about Moon

I was away this weekend at a family function and mostly without internet access, so I didn’t get to watch the coverage of the Moon landing for the first time in more than a decade. I also didn’t get to share a bunch of links I had up in browser tabs and now I think everyone is (justifiably) tired of all the Apollo 11 hoopla, myself included. But I hope you’ll indulge me in just one more and then I’ll (maybe! hopefully!) shut up about it for another year.

It’s tough to narrow it down, but the most dramatic & harrowing part of the whole mission is when Neil Armstrong notices that the landing site the LM (call sign “Eagle”) is heading towards is no good — it’s too rocky and full of craters — so he guides the spacecraft over that area to a better landing spot. He does this despite never having flown the LM that way in training, with program alarms going off, with Mission Control not knowing what he’s doing (he doesn’t have time to tell them), and with very low fuel. Eagle had an estimated 15-20 seconds of fuel left when they touched down and the guy doing the fuel callouts at Mission Control was basically just estimating the remaining fuel in his head based on how much flying he thinks the LM had done…and again, the LM had never been flown like that before and Mission Control didn’t know what Armstrong was up to! (The 13 Minutes to the Moon podcast does an excellent job explaining this bit of the mission, episode 9 in particular.)

Throughout this sequence, there was a camera pointed out Buzz Aldrin’s window — you can see that video here — but that was a slightly different view from Armstrong’s. We’ve never seen what Armstrong saw to cause him to seek out a new landing site. Now, a team at NASA has simulated the view out of his window using data from the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter Camera:

The LROC team reconstructed the last three minutes of the landing trajectory (latitude, longitude, orientation, velocity, altitude) using landmark navigation and altitude call outs from the voice recording. From this trajectory information, and high resolution LROC NAC images and topography, we simulated what Armstrong saw in those final minutes as he guided the LM down to the surface of the Moon. As the video begins, Armstrong could see the aim point was on the rocky northeastern flank of West crater (190 meters diameter), causing him to take manual control and fly horizontally, searching for a safe landing spot. At the time, only Armstrong saw the hazard; he was too busy flying the LM to discuss the situation with mission control.

This reconstructed view was actually pretty close to the camera’s view out of Aldrin’s window:

See also a photograph of the Apollo 11 landing site taken by the LRO camera from a height of 15 miles.

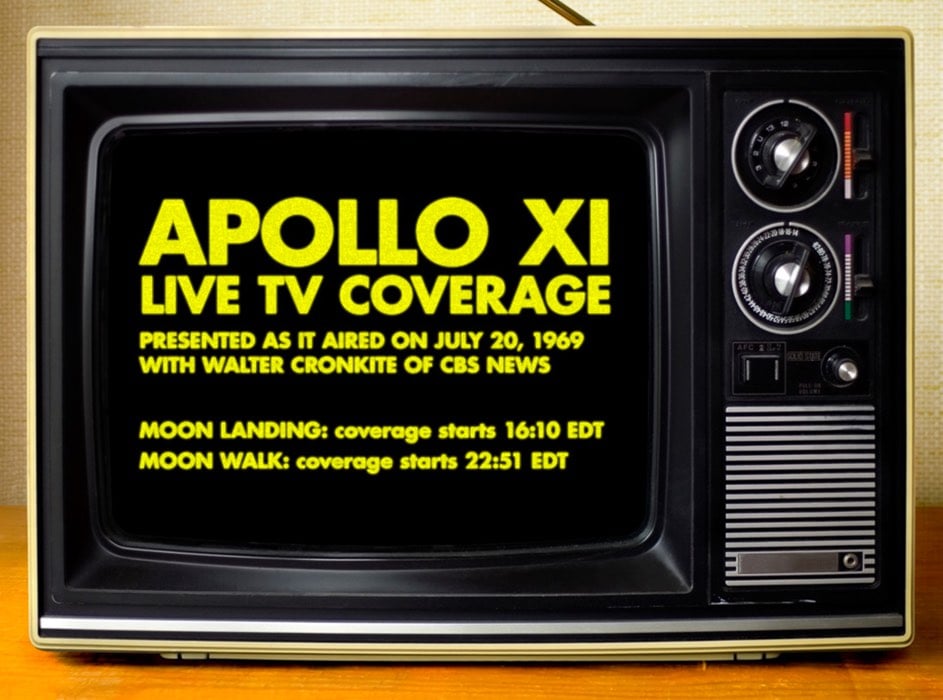

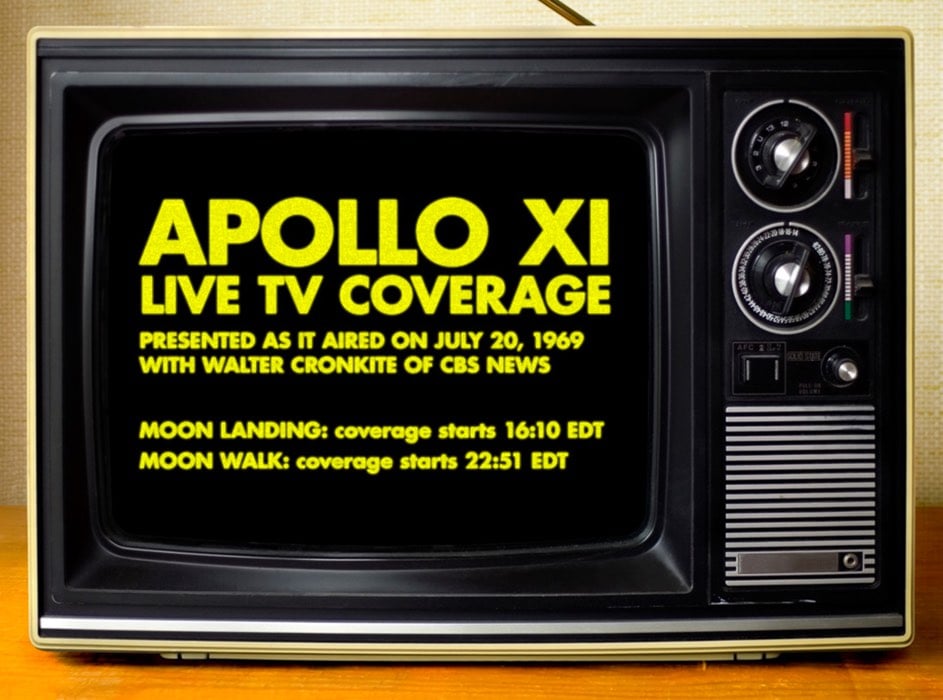

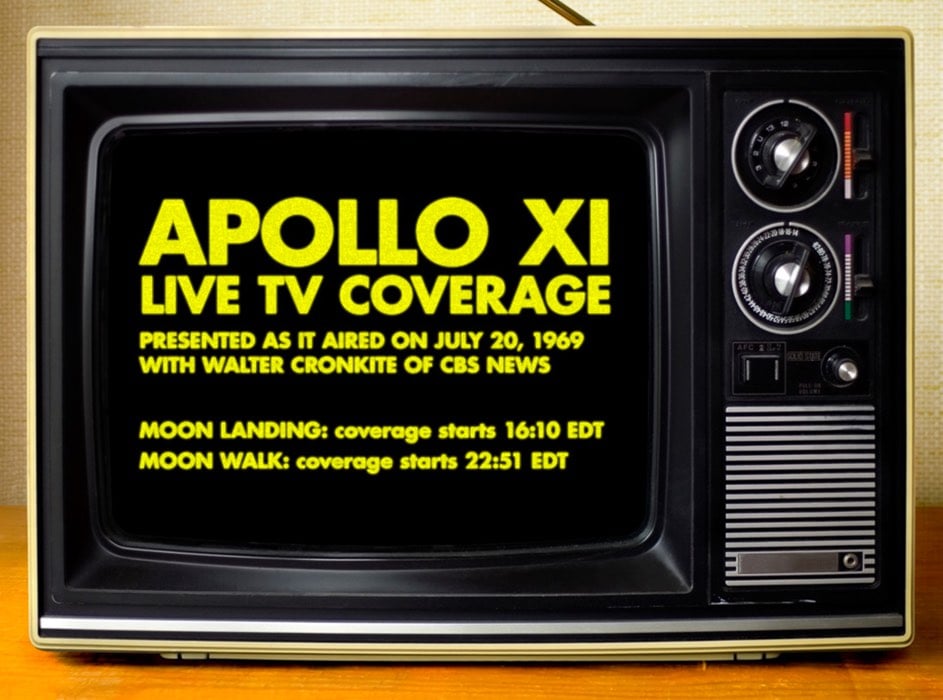

You’ve heard by now that it’s the 50th anniversary of the first humans landing on the Moon. On July 20, 1969, 50 years ago today, Neil Armstrong & Buzz Aldrin landed on the Moon and went for a little walk. For the 11th year in a row, you can watch the original CBS News coverage of Walter Cronkite reporting on the Moon landing and the first Moon walk on a small B&W television, synced to the present-day time. Just open this page in your browser today, July 20th, and the coverage will start playing at the proper time. Here’s the schedule (all times EDT):

4:10:30 pm: Moon landing broadcast starts

4:17:40 pm: Lunar module lands on the Moon

4:20:15 pm - 10:51:26 pm: Break in coverage

10:51:27 pm: Moon walk broadcast starts

10:56:15 pm: First step on Moon

11:51:30 pm: Nixon speaks to the Eagle crew

12:00:30 am: Broadcast end (on July 21)

Set an alarm on your phone or calendar!

This is one of my favorite things I’ve ever done online…here’s what I wrote when I launched the project in 2009:

If you’ve never seen this coverage, I urge you to watch at least the landing segment (~10 min.) and the first 10-20 minutes of the Moon walk. I hope that with the old time TV display and poor YouTube quality, you get a small sense of how someone 40 years ago might have experienced it. I’ve watched the whole thing a couple of times while putting this together and I’m struck by two things: 1) how it’s almost more amazing that hundreds of millions of people watched the first Moon walk *live* on TV than it is that they got to the Moon in the first place, and 2) that pretty much the sole purpose of the Apollo 11 Moon walk was to photograph it and broadcast it live back to Earth.

I wrote a bit last year about what to watch for during the landing sequence.

Two other things. You can also experience the landing and Moon walk live at Apollo 11 in Real Time. And it looks like CBS News is doing a livestream of Cronkite’s coverage of the landing on YouTube starting at 3:30pm. Nice to see them catching up! :)

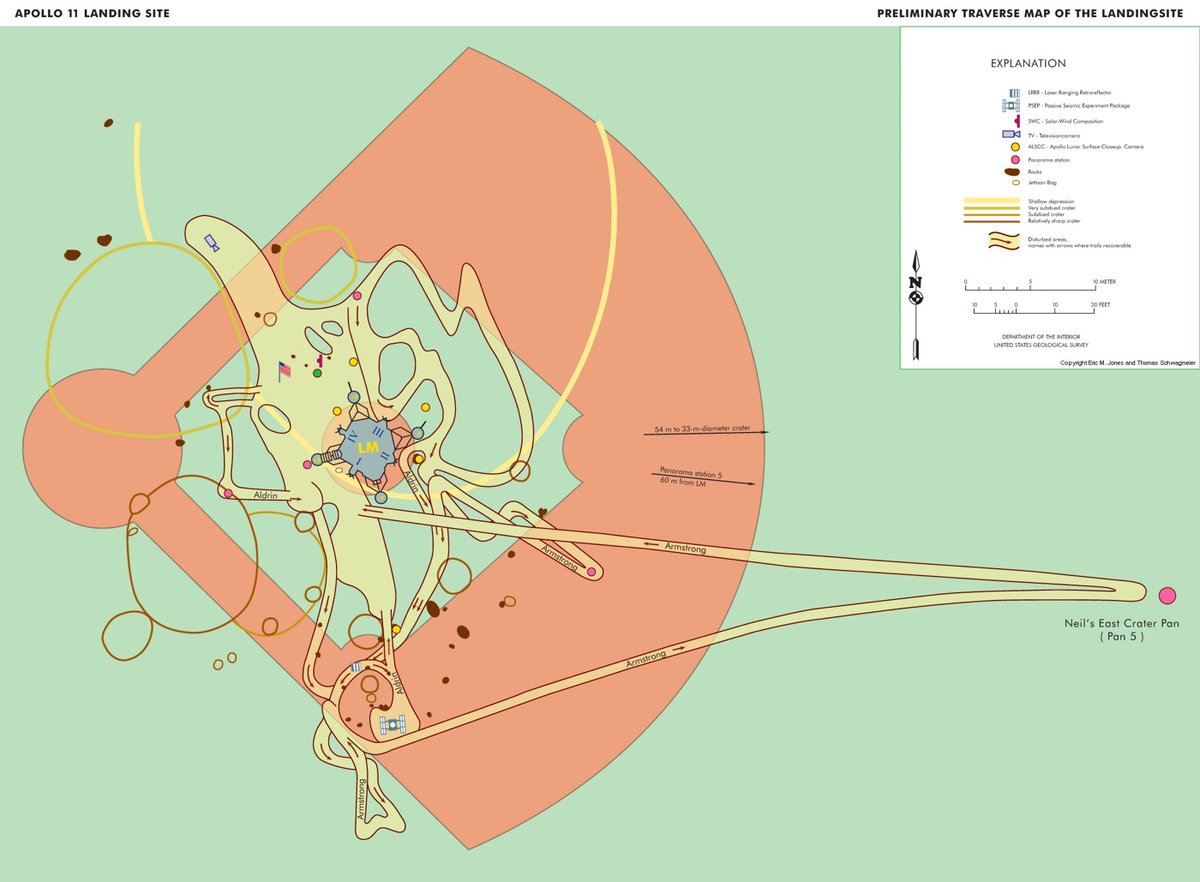

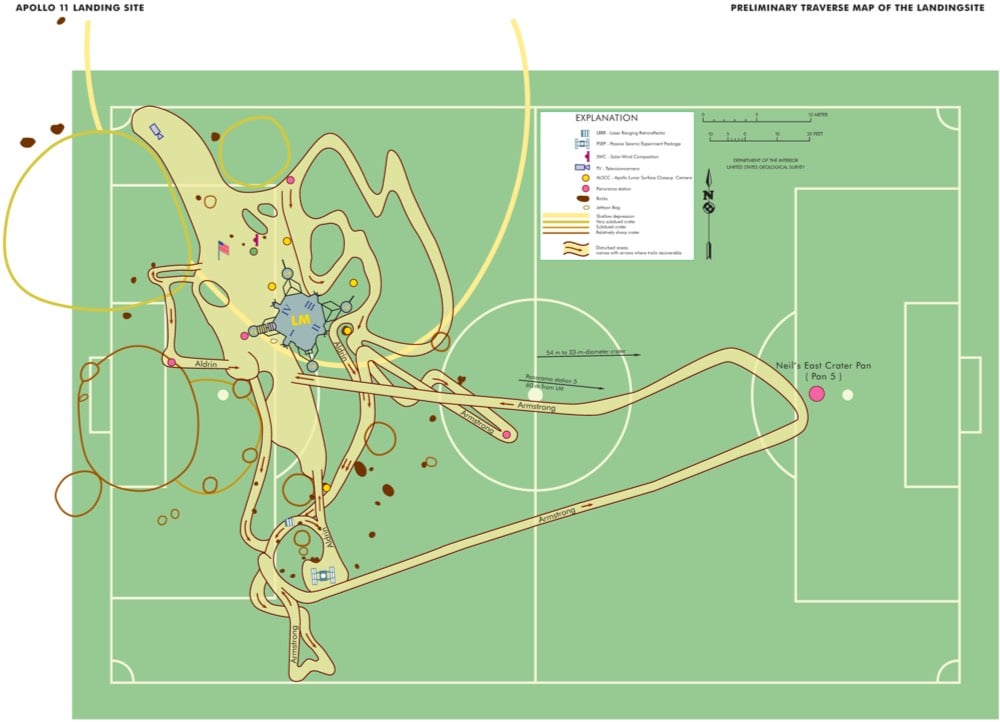

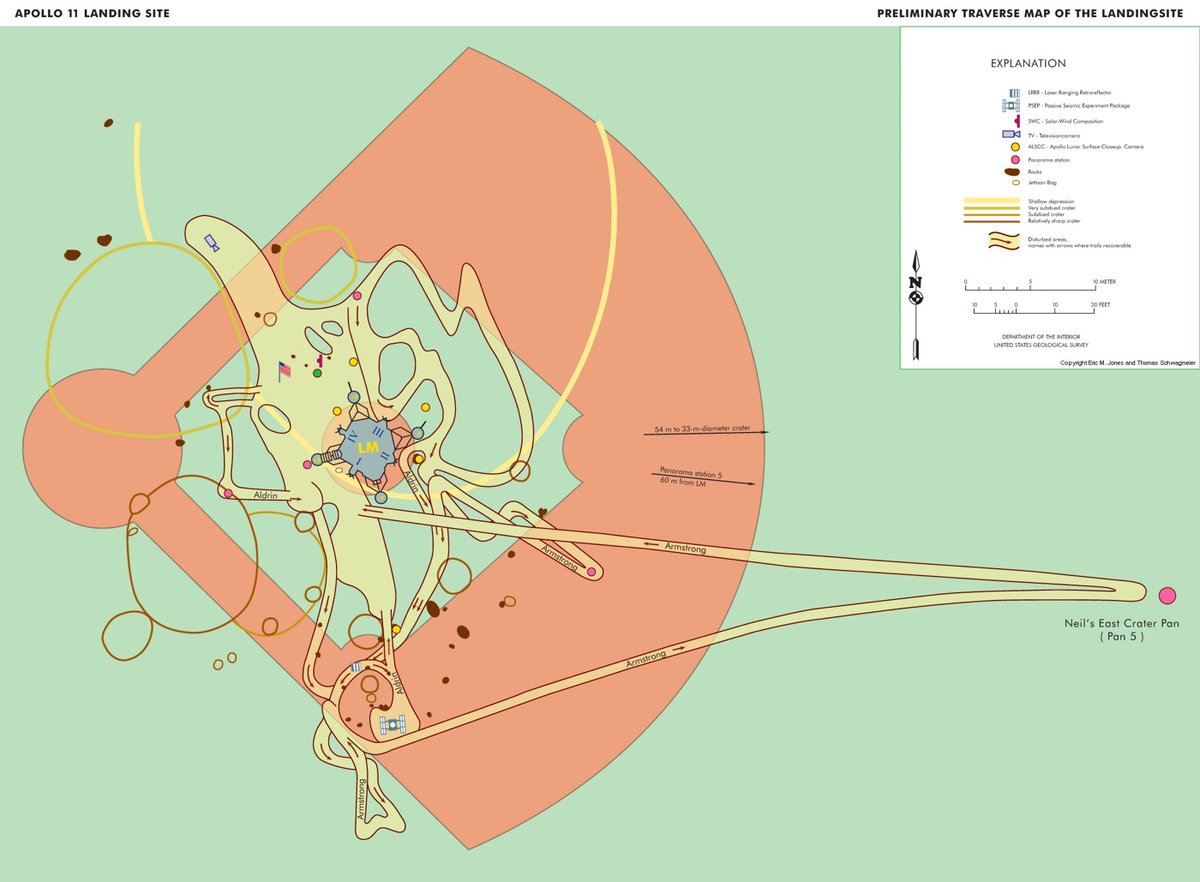

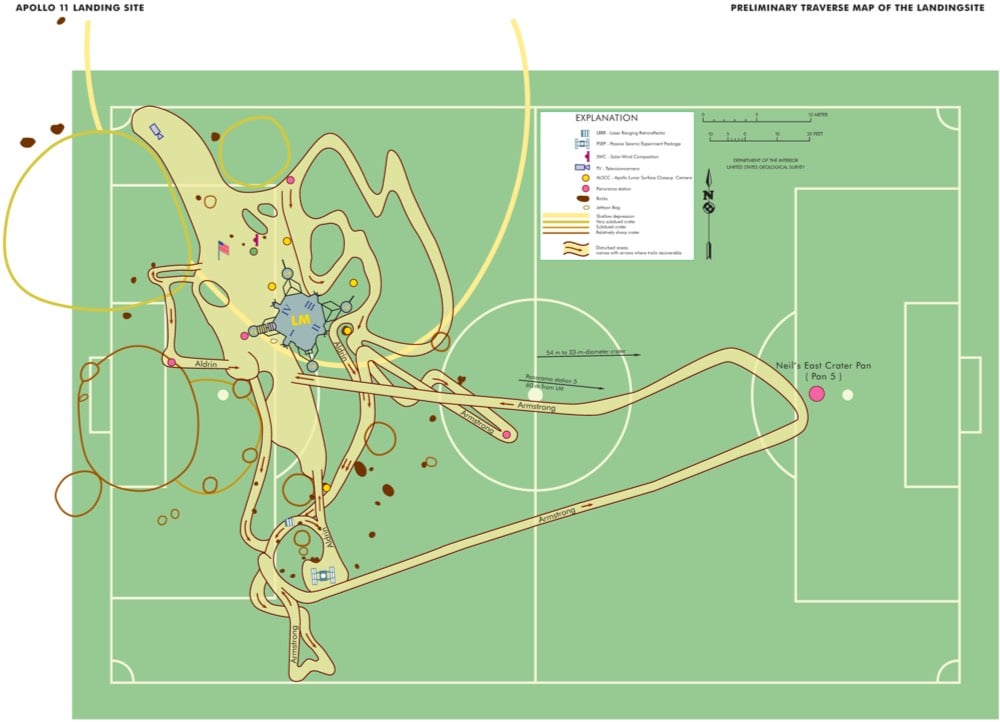

With the 50th anniversary of the first crewed landing on the Moon fast approaching, I thought I’d share one of my favorite views of the Moon walk, a map of where Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin walked on the Moon, superimposed over a baseball field (bigger). The Lunar Module is parked on the pitcher’s mound and you can see where the two astronauts walked, set up cameras, collected samples, and did experiments.

This map easily illustrates something you don’t get from watching video of the Moon walk: just how close the astronauts stayed to the LM and how small an area they covered during their 2 and 1/2 hours on the surface. The crew had spent 75+ hours flying 234,000 miles to the Moon and when they finally got out onto the surface, they barely left the infield! On his longest walk, Armstrong ventured into center field about 200 feet from the mound, not even far enough to reach the warning track in most major league parks. In fact, the length of Armstrong’s walk fell far short of the 363-foot length of the Saturn V rocket that carried him to the Moon and all of their activity could fit neatly into a soccer pitch (bigger):

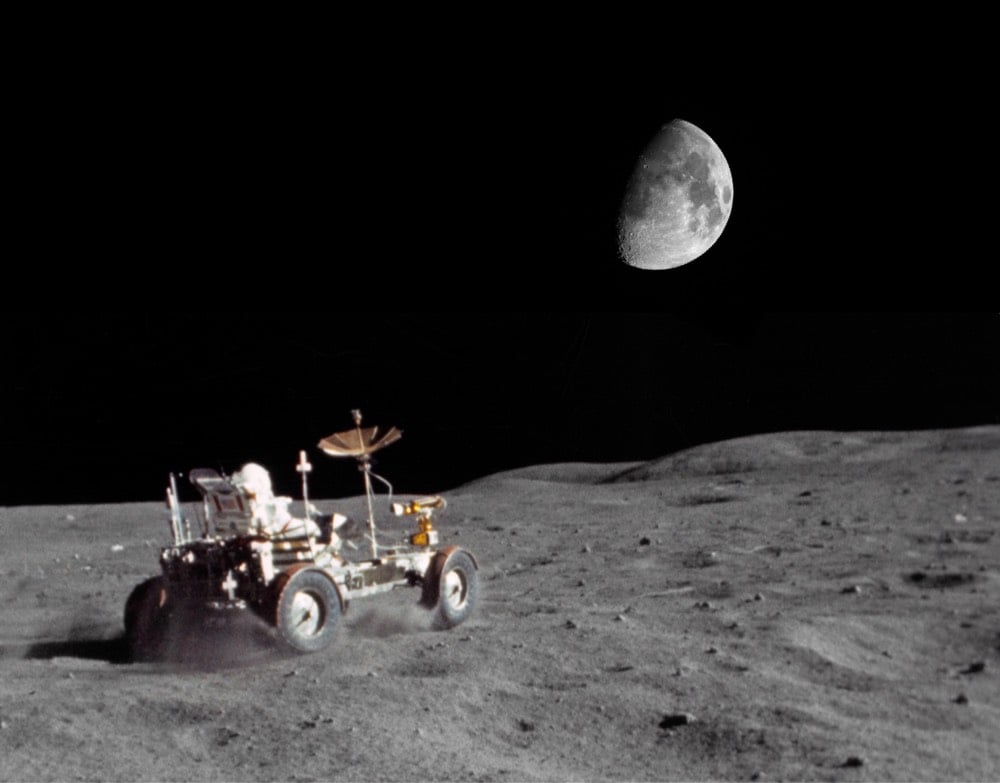

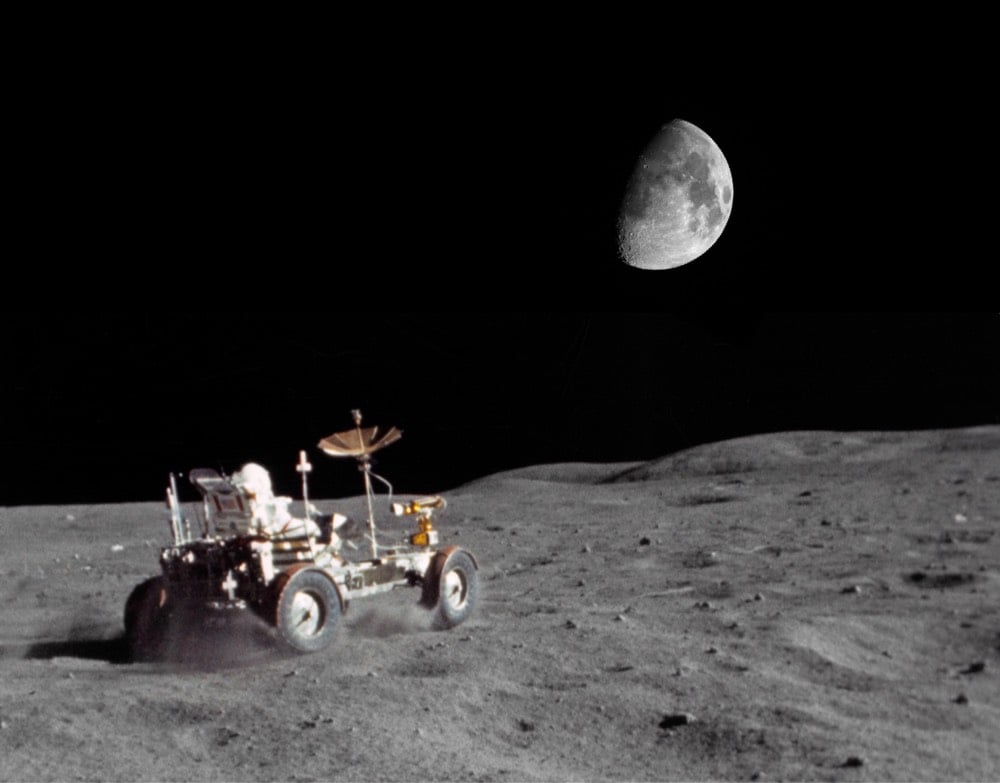

Astronauts on subsequent missions ventured much further. The Apollo 12 crew ventured 600 feet from the LM on their second walk of the mission. The Apollo 14 crew walked almost a mile. After the Lunar Rover entered the mix, excursions up to 7 miles during EVAs that lasted for more than 7 hours at a time became common.

The Apollo Flight Journal has put together a 20-minute video of the full descent and landing of the Apollo 11 Lunar Module containing Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin on July 20, 1969.

The video combines data from the onboard computer for altitude and pitch angle, 16mm film that was shot throughout the descent at 6 frames per second. The audio recording is from two sources. The air/ground transmissions are on the left stereo channel and the mission control flight director loop is on the right channel. Subtitles are included to aid comprehension.

Reminder that you can follow along in sync with the entire Apollo 11 mission right up until their splashdown. I am also doing my presentation of Walter Cronkite’s CBS news coverage of the landing and the Moon walk again this year, starting at 4:10pm EDT on Saturday, July 20. Here’s the post I wrote about it last year for more details. (thx, david)

Today, July 2, 2019, just after 4:30pm ET, a total solar eclipse will be visible in parts of Chile and Argentina. Because most of you, I am guessing, are not currently in those parts of Chile and Argentina, the best way to watch the eclipse is through any number of live streams, three of which I’m embedding here:

I was lucky enough to see the eclipse in 2017 and it was a life-altering experience, so I’ll be tearing myself away from the USA vs England match for a few minutes at least.

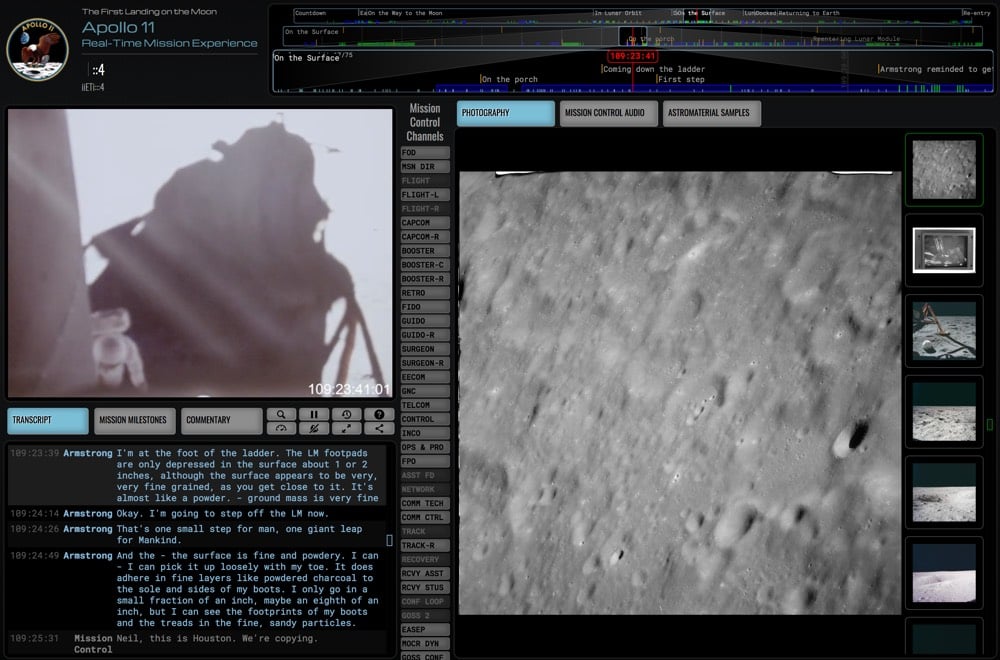

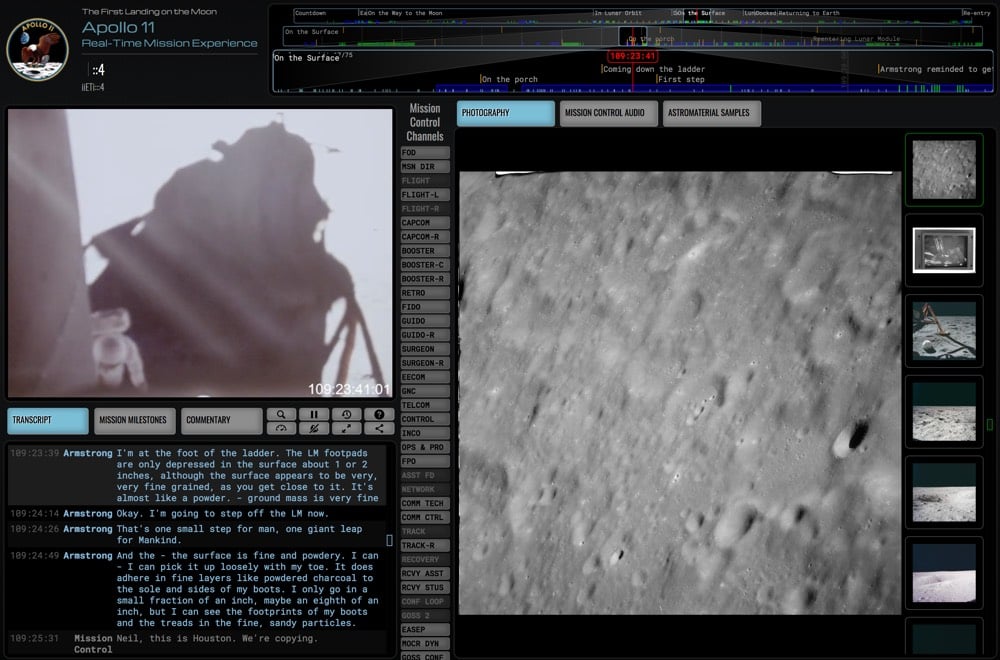

Well, this is just flat-out fantastic. Ben Feist and a team of collaborators have built Apollo 11 In Real Time, an interactive presentation of the first mission to land on the Moon as it happened.

This website replays the Apollo 11 mission as it happened, 50 years ago. It consists entirely of historical material, all timed to Ground Elapsed Time — the master mission clock. Footage of Mission Control, film shot by the astronauts, and television broadcasts transmitted from space and the surface of the Moon, have been painstakingly placed to the very moments they were shot during the mission, as has every photograph taken, and every word spoken.

You can tune in in real time beginning July 16th, watch/experience it right now from 1 minute before launch, or you can skip around the timeline to just watch the moments you want. As someone who has been hosting an Apollo 11 in real time thing for the past 9 years, this site makes me both ridiculously happy and a little bit jealous.

I’ve only ever seen footage of the first moonwalk in grainy videos as broadcast on TV, but this site shows it in the original resolution and it’s a revelation. Here’s the moonwalk, beginning with some footage of the folks in Mission Control nervously fidgeting with their hands (skip to 5:18:00 if the video doesn’t start there):

The rest of the video for the entire mission can be found here…what a trove. This whole thing is marvelous…I can’t wait to tune in when July 16th rolls around.

Charles Fishman has a new book, One Giant Leap, all about NASA’s Apollo program to land an astronaut on the moon. He talks about it on Fresh Air with Dave Davies.

On what computers were like in the early ’60s and how far they had to come to go to space

It’s hard to appreciate now, but in 1961, 1962, 1963, computers had the opposite reputation of the reputation they have now. Most computers couldn’t go more than a few hours without breaking down. Even on John Glenn’s famous orbital flight — the first U.S. orbital flight — the computers in mission control stopped working for three minutes [out] of four hours. Well, that’s only three minutes [out] of four hours, but that was the most important computer in the world during that four hours and they couldn’t keep it going during the entire orbital mission of John Glenn.

So they needed computers that were small, lightweight, fast and absolutely reliable, and the computers that were available then — even the compact computers — were the size of two or three refrigerators next to each other, and so this was a huge technology development undertaking of Apollo.

On the seamstresses who wove the computer memory by hand

There was no computer memory of the sort that we think of now on computer chips. The memory was literally woven … onto modules and the only way to get the wires exactly right was to have people using needles, and instead of thread wire, weave the computer program. …

The Apollo computers had a total of 73 [kilobytes] of memory. If you get an email with the morning headlines from your local newspaper, it takes up more space than 73 [kilobytes]. … They hired seamstresses. … Every wire had to be right. Because if you got [it] wrong, the computer program didn’t work. They hired women, and it took eight weeks to manufacture the memory for a single Apollo flight computer, and that eight weeks of manufacturing was literally sitting at sophisticated looms weaving wires, one wire at a time.

One anecdote that was new to me describes Armstrong and Aldrin test-burning moon dust, to make sure it wouldn’t ignite when repressurized.

Armstrong and Aldrin actually had been instructed to do a little experiment. They had a little bag of lunar dirt and they put it on the engine cover of the ascent engine, which was in the middle of the lunar module cabin. And then they slowly pressurized the cabin to make sure it wouldn’t catch fire and it didn’t. …

The smell turns out to be the smell of fireplace ashes, or as Buzz Aldrin put it, the smell of the air after a fireworks show. This was one of the small but sort of delightful surprises about flying to the moon.

In July, American Experience will air Chasing the Moon, a 6-hour documentary film about the effort to send a manned mission to the Moon before the end of the 1960s.

The series recasts the Space Age as a fascinating stew of scientific innovation, political calculation, media spectacle, visionary impulses and personal drama. Utilizing a visual feast of previously overlooked and lost archival material — much of which has never before been seen by the public — the film features a diverse cast of characters who played key roles in these historic events. Among those included are astronauts Buzz Aldrin, Frank Borman and Bill Anders; Sergei Khrushchev, son of the former Soviet premier and a leading Soviet rocket engineer; Poppy Northcutt, a 25-year old “mathematics whiz” who gained worldwide attention as the first woman to serve in the all-male bastion of NASA’s Mission Control; and Ed Dwight, the Air Force pilot selected by the Kennedy administration to train as America’s first black astronaut.

Among the stories not usually told about the Moon missions is that of Ed Dwight, NASA’s first black astronaut trainee:

Since 2019 is the 50th anniversary of the Apollo 11 mission, there’s a *lot* of stuff out there about the Space Race and Apollo program, but this film looks like it’s going to be one of the best. The film will start airing on PBS on July 8 and the Blu-ray & DVD comes out on July 9. There’s a companion book that will be available next week.

In commemoration of the 50th anniversary of the Apollo 11 Moon landing, the USPS is releasing a pair of stamps with lunar imagery.

One stamp features a photograph of Apollo 11 astronaut Buzz Aldrin in his spacesuit on the surface of the moon. The image was taken by astronaut Neil Armstrong. The other stamp, a photograph of the moon taken in 2010 by Gregory H. Revera of Huntsville, AL, shows the landing site of the lunar module in the Sea of Tranquility. The site is indicated on the stamp by a dot.

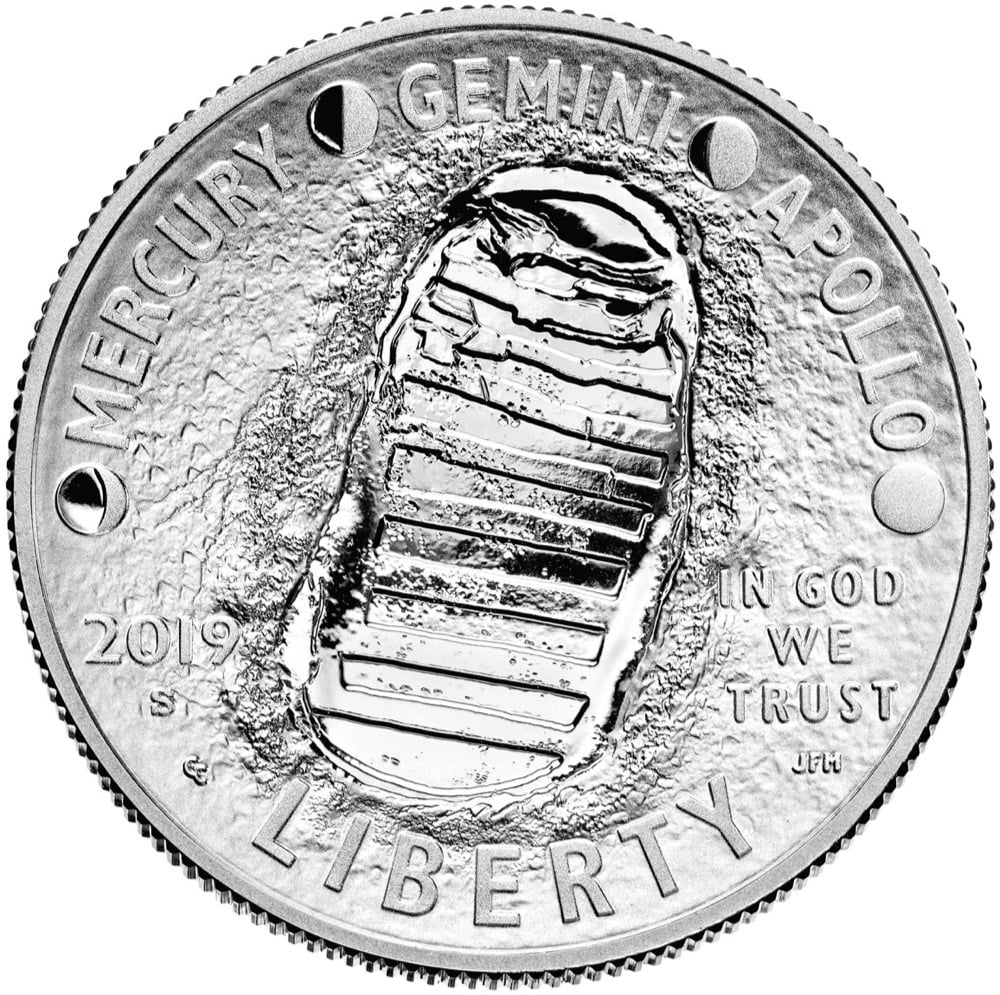

These pair nicely with the US Mint’s Apollo 11 commemorative coins.

(via swissmiss)

We’re coming up on the 50th anniversary of the Apollo 11 mission, which means an increase in Apollo 11 media. This is a strong early entrant: “Apollo 11”, a feature-length documentary on the mission, featuring “a newly discovered trove of 65mm footage” of starting clarity.

Miller and his team collaborated with NASA and the National Archives (NARA) to locate all of the existing footage from the Apollo 11 mission. In the course of sourcing all of the known imagery, NARA staff members made a discovery that changed the course of the project — an unprocessed collection of 65mm footage, never before seen by the public. Unbeknownst to even the NARA archivists, the reels contained wide format scenes of the Saturn V launch, the inside of the Launch Control Center and post-mission activities aboard the USS Hornet aircraft carrier.

The find resulted in the project evolving from one of only filmmaking to one of also film curation and historic preservation. The resulting transfer — from which the documentary was cut — is the highest resolution, highest quality digital collection of Apollo 11 footage in existence.

The film is 100% archival footage and audio. They’ve paired the footage with selections from 11,000 hours of mission audio.

The other unexpected find was a massive cache of audio recordings — more than 11,000 hours — comprising the individual tracks from 60 members of the Mission Control team. “Apollo 11” film team members wrote code to restore the audio and make it searchable and then began the multi-year process of listening to and documenting the recordings. The effort yielded new insights into key events of the moon landing mission, as well as surprising moments of humor and camaraderie.

This. Sounds. Amazing. The film premiered at the Sundance Film Festival a few days ago and the reviews have been overwhelmingly positive. Here’s David Erhlich writing for Indiewire:

It’s rare that picture quality can inspire a physical reaction, but the opening moments of “Apollo 11,” in which a NASA camera crew roams around the base of the rocket and spies on some of the people who’ve come to gawk at it from a beach across the water, are vivid enough to melt away the screen that stands between them. The clarity takes your breath away, and it does so in the blink of an eye; your body will react to it before your brain has time to process why, after a lifetime of casual interest, you’re suddenly overcome by the sheer enormity of what it meant to leave the Earth and land somewhere else. By tricking you at a base sensory level into seeing the past as though it were the present, Miller cuts away the 50 years that have come between the two, like a heart surgeon who cuts away a dangerous clot so that the blood can flow again. Such perfect verisimilitude is impossible to fake.

And Daniel Fienberg for The Hollywood Reporter:

Much of the footage in Apollo 11 is, by virtue of both access and proper preservation, utterly breathtaking. The sense of scale, especially in the opening minutes, sets the tone as rocket is being transported to the launch pad and resembles nothing so much as a scene from Star Wars only with the weight and grandeur that come from 6.5 million pounds of machinery instead of CG. The cameraman’s astonishment is evident and it’s contagious. The same is true of long tracking shots through the firing room as the camera moves past row after row after row of computers, row after row after row of scientists and engineers whose entire professional careers have led to this moment.

There will be a theatrical release (including what sounds like an IMAX release for museums & space centers) followed by a showing on TV by CNN closer to July.

Something incredible happened during the super blood wolf moon eclipse that took place on Sunday night: a meteorite struck the moon during the eclipse and it was captured on video, the first time this has ever happened.

Jose Maria Madiedo at the University of Huelva in Spain has confirmed that the impact is genuine. For years, he and his colleagues have been hoping to observe a meteorite impact on the moon during a lunar eclipse, but the brightness of these events can make that very difficult — lunar meteorite impacts have been filmed before, but not during an eclipse.

The 4K video of the impact above was taken by amateur astronomer Deep Sky Dude in Texas…he notes the impact happening at 10:41pm CST. I couldn’t find any confirmation on this, but the impact looks bright enough that it may have been visible with the naked eye if you were paying sufficient attention to the right area at the right time.

Phil Plait has a bunch more info on the impact. If the impact site can be accurately determined, NASA will attempt to send the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter to get photos of it.

Interestingly, I talked to Noah Petro, Project Scientist for LRO, and he noted that the impact may have created secondary craters, smaller ones made by debris blown out by the main impact. Those will spread out over a larger area, and are easier to spot, so it’s possible that even with a rough location known beforehand the crater can be found. Also, fresh craters look distinct from older ones — they’re brighter, and have a bright fresh splash pattern around them — so once it’s in LRO’s sights it should be relatively easy to spot.

It’s not clear how big the crater will be. I’ve seen some estimates that the rock that hit was probably no more than a dozen kilograms or so, and the crater will be probably 10 meters across. That’s small, but hopefully its freshness will make it stand out.

Equipped with only a magnifying glass and the light of the Sun, it’s pretty easy to start a fire.1 So, with a much bigger glass, could you start a fire with moonlight?

First, here’s a general rule of thumb: You can’t use lenses and mirrors to make something hotter than the surface of the light source itself. In other words, you can’t use sunlight to make something hotter than the surface of the Sun.

There are lots of ways to show why this is true using optics, but a simpler — if perhaps less satisfying — argument comes from thermodynamics:

Lenses and mirrors work for free; they don’t take any energy to operate.[2] If you could use lenses and mirrors to make heat flow from the Sun to a spot on the ground that’s hotter than the Sun, you’d be making heat flow from a colder place to a hotter place without expending energy. The second law of thermodynamics says you can’t do that. If you could, you could make a perpetual motion machine.

In a better world, Randall Munroe would be writing middle school science textbooks.

Using 3D rendering software, Yeti Dynamics made this video that shows what our sky would look like if several of our solar system’s planets orbited the Earth in place of the Moon. If you look closely when Saturn and Jupiter are in the sky, you can see their moons as well.

the moon that flies in front of Saturn is Tethys. It is Tiny. but *very* close. Dione would be on a collision course, it’s orbital distance from Saturn is Nearly identical to our Moon’s orbit around Earth

See also their video of what the Moon would look like if it orbited the Earth at the same distance as the International Space Station.

Update: And here’s what it would look like if the Earth had Saturn’s rings. (via @FormingWorship)

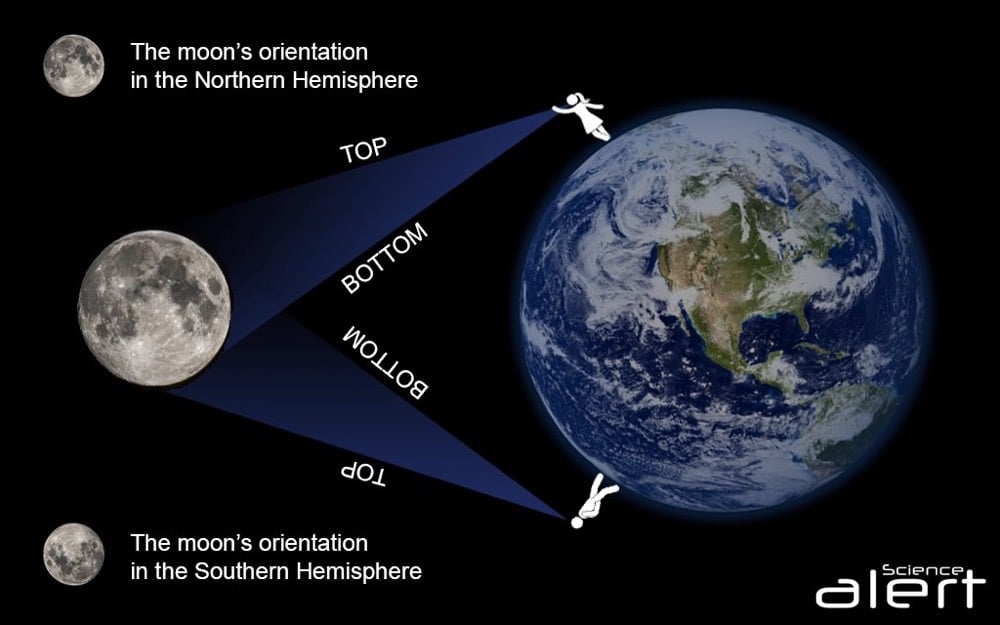

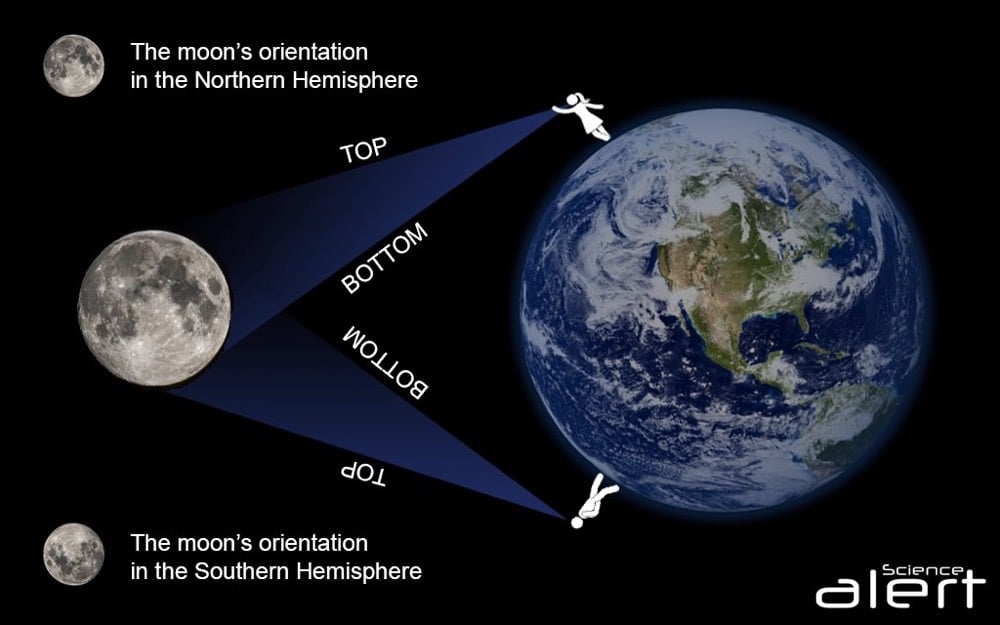

How old were you when you learned that the Moon in the Southern Hemisphere is upside down? I was today years old…this is my head exploding —> %@*&!$. Ok, the Moon isn’t upside down (that’s Northern-ist) but its orientation changes depending on if you’re north or south of the equator.

“From our perspective, the Moon and the night sky is actually rotated 180 degrees compared to our Northern Hemispherical friends,” Jake Clark, an astronomer from the University of Southern Queensland in Australia, explained to ScienceAlert.

“In the south we see the Moon’s dark ‘Oceanus Procellarum’ sea in the south-east corner compared to in the north-west corner for a northern observer.”

But why does it look like this? Well, because physically, we’re actually upside down compared to someone standing in the opposite hemisphere.

That makes perfect sense & the explanation is quite simple but it’s still messing with my head. How did I not know this? Here’s how the Moon appears in the Northern Hemisphere (from Wikipedia):

And here’s a photo from Brendan Keene in Australia:

The NY times recently asked eight artists what art projects they would do if they could fly to the Moon. Here’s Kara Walker’s answer:

Gil Scott Heron wrote that famous poem, “Whitey on the Moon”: “The man just upped my rent last night / Cause whitey’s on the moon / No hot water, no toilets, no lights / But whitey’s on the moon.”

I got thinking about a moon colony, which plenty of people have talked about pretty seriously over the years. So what I’d do is this: For every female child born on Earth, one sexist, white supremacist adult male would be shipped to the moon. They could colonize it to their heart’s content, and look down from a distance of a quarter-million miles. It’s a monochrome world up there; probably they’d love it. The colony would be hermetically sealed. And the rest of us could enjoy the sight of them from a safe distance. Maybe there could be some kind of selection ritual involved, something to do with menstruation and the tides — a touch of nature, to add a bit of irony justice to the endeavor.

For the supremacists, maybe traveling so far from home would help inspire a different worldview. And for the rest of us down on Earth, perhaps this is an opportunity to focus on the nature of our home planet with the same dreamy reverence we once reserved for the moon.

Here’s Scott-Heron’s Whitey on the Moon. In contrast, architect Daniel Libeskind would turn the Moon into a square by painting part of it black:

My son Noam is an astrophysicist at the Leibniz Institute in Germany, and we did some calculations about how it could work. We thought the best way would be to paint sections of it black, so they no longer reflect the sun’s light. To account for the curvature, you’d need to paint four spherical caps on the moon’s surface. That would create a kind of frame that looks square when you see it from earth.

In a paper called “Can Moons Have Moons?”, a pair of astronomers says that some of the solar system’s moons, including ours, are large enough and far enough away from their host planets to have their own sizable moons.

We find that 10 km-scale submoons can only survive around large (1000 km-scale) moons on wide-separation orbits. Tidal dissipation destabilizes the orbits of submoons around moons that are small or too close to their host planet; this is the case for most of the Solar System’s moons. A handful of known moons are, however, capable of hosting long-lived submoons: Saturn’s moons Titan and Iapetus, Jupiter’s moon Callisto, and Earth’s Moon.

Throughout the paper, the authors refer to these possible moons of moons as “submoons” but a much more compelling name has been put forward: “moonmoons”.

Moonmoon is an example of the linguistic process of reduplication, which is often deployed in English to make things more cute and whimsical. In the pure form of reduplication, you get words like bonbon, choo-choo, bye-bye, there there, and moonmoon but relaxing the rules a little to incorporate rhymes and near-rhymes yields hip-hop, zig-zag, fancy-shmancy, super-duper, pitter-patter, and okey-dokey. And with contrastive reduplication, in which a word repeats as a modifier to itself:

“It’s tuna salad, not salad-salad.”

“Does she like me or like-like me?”

“The party is fancy but not fancy-fancy.”

“The car isn’t mine-mine, it’s my mom’s.”

Fun! And astronomy should be fun too. Let’s definitely call them moonmoons.

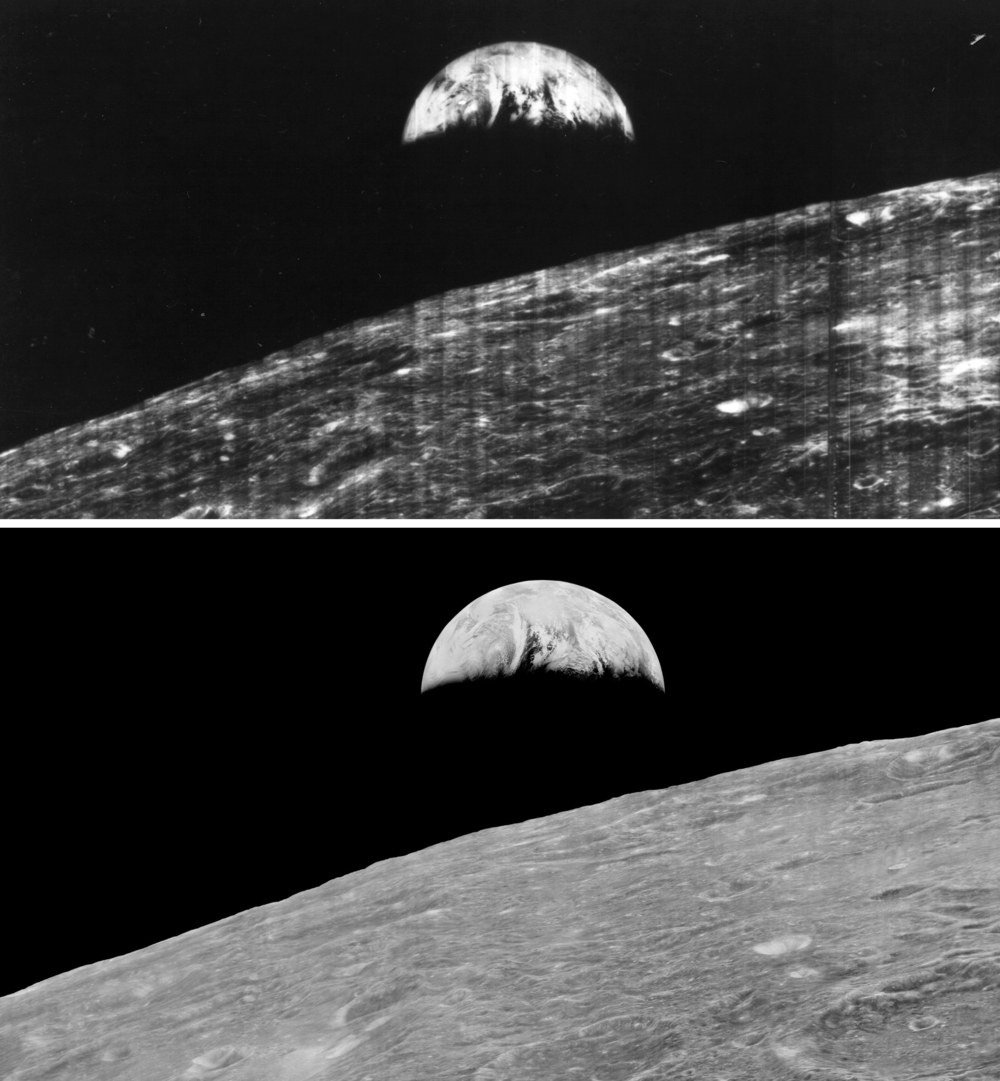

In 1968, the crew of Apollo 8 became the first ever humans to leave the cozy confines of Earth orbit. From Wikipedia:

The three-astronaut crew — Commander Frank Borman, Command Module Pilot James Lovell, and Lunar Module Pilot William Anders — became the first humans to travel beyond low Earth orbit; see Earth as a whole planet; enter the gravity well of another celestial body (Earth’s moon); orbit another celestial body (Earth’s moon); directly see the far side of the Moon with their own eyes; witness an Earthrise; escape the gravity of another celestial body (Earth’s moon); and re-enter the gravitational well of Earth.

That’s a substantial list of firsts. But before setting out on the mission, neither the crew or anyone else at NASA gave much thought to perhaps the most significant and long-lasting achievements on that list: “see Earth as a whole planet” and “witness an Earthrise”. In this gem of a short film by Emmanuel Vaughan-Lee, Anders, Borman, and Lovell recall what it was like for them to be the first of only 24 people to see, with their own eyes, the Earth from that distance, a blue marble hanging in the inky blackness of space.

What they should have sent was poets, because I don’t think we captured the grandeur of what we’d seen.

The day after Apollo 8 orbited the Moon, a poem by Archibald Macleish published on the front page of the NY Times tried to capture that grandeur: Riders on Earth Together, Brothers in Eternal Cold.

Men’s conception of themselves and of each other has always depended on their notion of the earth. When the earth was the World — all the world there was — and the stars were lights in Dante’s heaven, and the ground beneath men’s feet roofed Hell, they saw themselves as creatures at the center of the universe, the sole, particular concern of God — and from that high place they ruled and killed and conquered as they pleased.

And when, centuries later, the earth was no longer the World but a small, wet spinning planet in the solar system of a minor star off at the edge of an inconsiderable galaxy in the immeasurable distances of space — when Dante’s heaven had disappeared and there was no Hell (at least no Hell beneath the feet) — men began to see themselves not as God-directed actors at the center of a noble drama, but as helpless victims of a senseless farce where all the rest were helpless victims also and millions could be killed in world-wide wars or in blasted cities or in concentration camps without a thought or reason but the reason — if we call it one — of force.

Now, in the last few hours, the notion may have changed again. For the first time in all of time men have seen it not as continents or oceans from the little distance of a hundred miles or two or three, but seen it from the depth of space; seen it whole and round and beautiful and small as even Dante — that “first imagination of Christendom” — had never dreamed of seeing it; as the Twentieth Century philosophers of absurdity and despair were incapable of guessing that it might be seen. And seeing it so, one question came to the minds of those who looked at it. “Is it inhabited?” they said to each other and laughed — and then they did not laugh. What came to their minds a hundred thousand miles and more into space — “half way to the moon” they put it — what came to their minds was the life on that little, lonely, floating planet; that tiny raft in the enormous, empty night. “Is it inhabited?”

The medieval notion of the earth put man at the center of everything. The nuclear notion of the earth put him nowhere — beyond the range of reason even — lost in absurdity and war. This latest notion may have other consequences. Formed as it was in the minds of heroic voyagers who were also men, it may remake our image of mankind. No longer that preposterous figure at the center, no longer that degraded and degrading victim off at the margins of reality and blind with blood, man may at last become himself.

To see the earth as it truly is, small and blue and beautiful in that eternal silence where it floats, is to see ourselves as riders on the earth together, brothers on that bright loveliness in the eternal cold — brothers who know now they are truly brothers.

This video explores how humans could begin to colonize the Moon today, using currently available technology.

We actually do have the technology and current estimates from NASA and the private sector say it could be done for $20-40 billion spread out over about a decade. The price is comparable to the International Space Station or the budget surplus of Germany in 2017.

That’s also only 12-25% of the net worth of Jeff Bezos. I don’t know whether that’s more an illustration of the relative affordability of building a Moon base or of Bezos’ wealth, but either way it’s a little bit crazy that the world’s richest man can easily afford to fund the building of a Moon base and somehow it’s not happening (or even close to happening).

For more than 35 years, Dennis Hope has been selling land on the Moon. Hope registered a claim for the Moon in 1980 and, since the US government & the UN didn’t object, he figures he owns it (along with the other planets and moons in the solar system).

“I sent the United Nations a declaration of ownership detailing my intent to subdivide and sell the moon and have never heard back,” he says. “There is a loophole in the treaty — it does not apply to individuals.”

The US government had several years to contest such a claim. which they never did. Neither did the United Nations nor the Russian Government. This allowed Mr. Hope to take the next step and copyright his work with the US Copyright registry office. So, with his claim and Copyright Registration Certificate from the US Government in hand, Mr. Hope became what is probably the largest landowner on the planet today.

An acre-sized plot of the Moon is currently available for $24.99 and Hope says he has sold over a billion acres of his celestial properties to more than 6 million people, including to such moonsteaders as George H.W. Bush, Ronald Reagan, and Star Trek cast members.

NASA recently published this visualization of sunrises and sunsets on the Moon set to the strains of Claude Debussy’s most famous work, Clair de Lune.

The visuals were composed like a nature documentary, with clean cuts and a mostly stationary virtual camera. The viewer follows the Sun throughout a lunar day, seeing sunrises and then sunsets over prominent features on the Moon. The sprawling ray system surrounding Copernicus crater, for example, is revealed beneath receding shadows at sunrise and later slips back into darkness as night encroaches.

A lovely way to spend five minutes. (thx, gina)

I have been going a little Moon crazy lately. There was the whole Apollo 11 thing, I finished listening to the excellent audiobook of Andrew Chaikin’s A Man on the Moon (which made me feel sad for a lot of different reasons), and am thinking about a rewatch of From the Earth to the Moon, the 1998 HBO series based on Chaikin’s book. This video from National Geographic answers a lot of questions about the Moon in a short amount of time.

In May 1961, President John F. Kennedy stood before Congress and said:

I believe that this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to the earth.

A little more than 8 years later, it was done. On July 20, 1969, 49 years ago today, Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin landed on the Moon, took a walk, and returned safely to Earth a few days later. And the whole thing was broadcast live on television screens around the world.

For the 40th anniversary of the landing in 2009, I put together a page where you can watch the original CBS News coverage of Walter Cronkite reporting on the Moon landing and the first Moon walk, synced to the present-day time. Just open this page in your browser and the coverage will start playing at the proper time. Here’s the schedule (all times EDT):

4:10:30 pm: Moon landing broadcast starts

4:17:40 pm: Lunar module lands on the Moon

4:20:15 pm: Break in coverage

10:51:27 pm: Moon walk broadcast starts

10:56:15 pm: First step on Moon

11:51:30 pm: Nixon speaks to the Eagle crew

12:00:30 am: Broadcast end (on July 21)

You can add these yearly recurring events to your calendar: Moon landing & Moon walk.

Here’s what I wrote when I launched the project, which is one of my favorite things I’ve ever done online:

If you’ve never seen this coverage, I urge you to watch at least the landing segment (~10 min.) and the first 10-20 minutes of the Moon walk. I hope that with the old time TV display and poor YouTube quality, you get a small sense of how someone 40 years ago might have experienced it. I’ve watched the whole thing a couple of times while putting this together and I’m struck by two things: 1) how it’s almost more amazing that hundreds of millions of people watched the first Moon walk *live* on TV than it is that they got to the Moon in the first place, and 2) that pretty much the sole purpose of the Apollo 11 Moon walk was to photograph it and broadcast it live back to Earth.

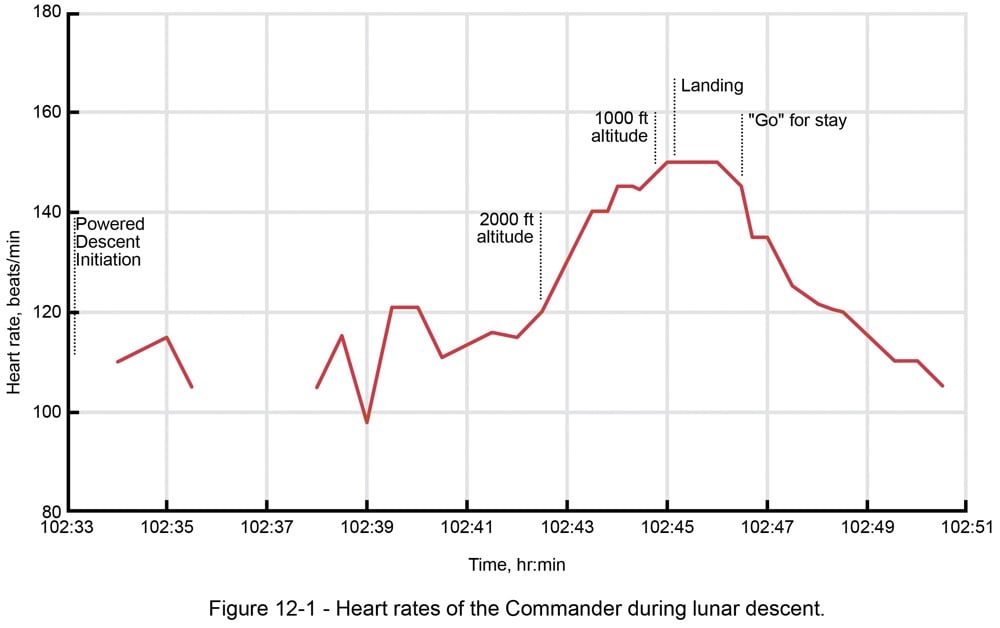

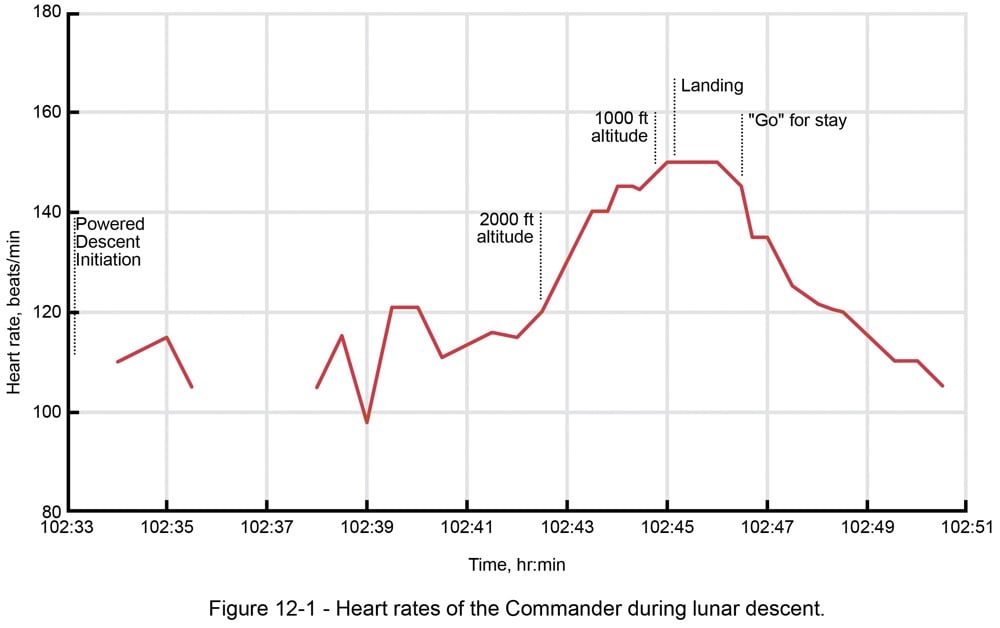

I’ve been listening to the audiobook of Andrew Chaikin’s account of the Apollo program, A Man on the Moon, and the chapter about Apollo 11’s Moon landing was riveting.1 I’ve watched the TV footage & listened to the recordings dozens of times and I was still on the edge of my seat, sweating the landing alongside Armstrong and Aldrin. And sweating they were…at least Armstrong was. Take a look at his heart rate during the landing; it peaked at 150 beats per minute at landing (note: the “1000 ft altitude” is mislabeled, it should be “100 ft”):

For reference, Armstrong’s resting heart rate was around 60 bpm. There are a couple of other interesting things about this chart. The first is the two minutes of missing data starting around 102:36. They were supposed to be 10 minutes from landing on the Moon and instead their link to Mission Control in Houston kept cutting out. Then there were the intermittent 1201 and 1202 program alarms, which neither the LM crew nor Houston had encountered in any of the training simulations. At the sign of the first alarm at 102:38:26, Armstrong’s heart rate actually appears to drop. And then, as the alarms continue throughout the sequence along with Houston’s assurances that the alarm is nothing to worry about, Armstrong’s heart rate stays steady.

Right around the 2000 feet mark, Armstrong realizes that he needs to maneuver around a crater and some rocks on the surface to reach a flat landing spot and his heart rate steadily rises until it plateaus at the landing. At the time, he thought he’d landed with less than 30 seconds of fuel remaining. That Neil Armstrong was able to keep his cool with unknown alarms going off while avoiding craters and boulders with very little fuel remaining and his heart rate spiking while skimming over the surface OF THE FREAKING MOON doing something no one had ever done before is one of the most totally cold-blooded & badass things anyone has ever done. Damn, I get goosebumps just reading about it!

Update: The landing broadcast just aired and I wanted to explain a little about what you saw (you can relive it here).

The shots of the Moon you see during the landing broadcast are animations…there is obviously no camera on the Moon watching the LM descend to the surface. There was a camera recording the landing from the LM but that footage was not released until later. This is in contrast to the footage you’ll see later on the Moon walk broadcast…that footage was piped in live to TV screens all over the world as it happened.

The radio voices you hear are mostly Mission Control in Houston (specifically Apollo astronaut Charlie Duke, who acted as the spacecraft communicator for this mission) and Buzz Aldrin, whose job during the landing was to keep an eye on the LM’s altitude and speed — you can hear him calling it out, “3 1/2 down, 220 feet, 13 forward.” Armstrong doesn’t say a whole lot…he’s busy flying and furiously searching for a suitable landing site. But it’s Armstrong that says after they land, “Houston, Tranquility Base here. The Eagle has landed.”. Note the change in call sign from “Eagle” to “Tranquility Base”. :)

Two things to listen for on the broadcast: the 1201/1202 program alarms I mentioned above and two quick callouts by Charlie Duke about the remaining fuel towards the end: “60 seconds” and “30 seconds”. Armstrong is taking all this information in through his earpiece — the 1202s, the altitude and speed from Aldrin, and the remaining fuel — and using it to figure out where to land.

The CBS animation shows the fake LM landing on the fake Moon before the actual landing — when Buzz says “contact light” and then “engine stop”. The animation was based on the scheduled landing time and evidently couldn’t be adjusted. The scheduled time was overshot because of the crater and boulders situation mentioned above.

Cronkite was joined on the program by former astronaut Wally Schirra. When Armstrong signaled they’d landed, Schirra can be seen dabbing his eyes and Cronkite looks a little misty as well as he rubs his hands together.

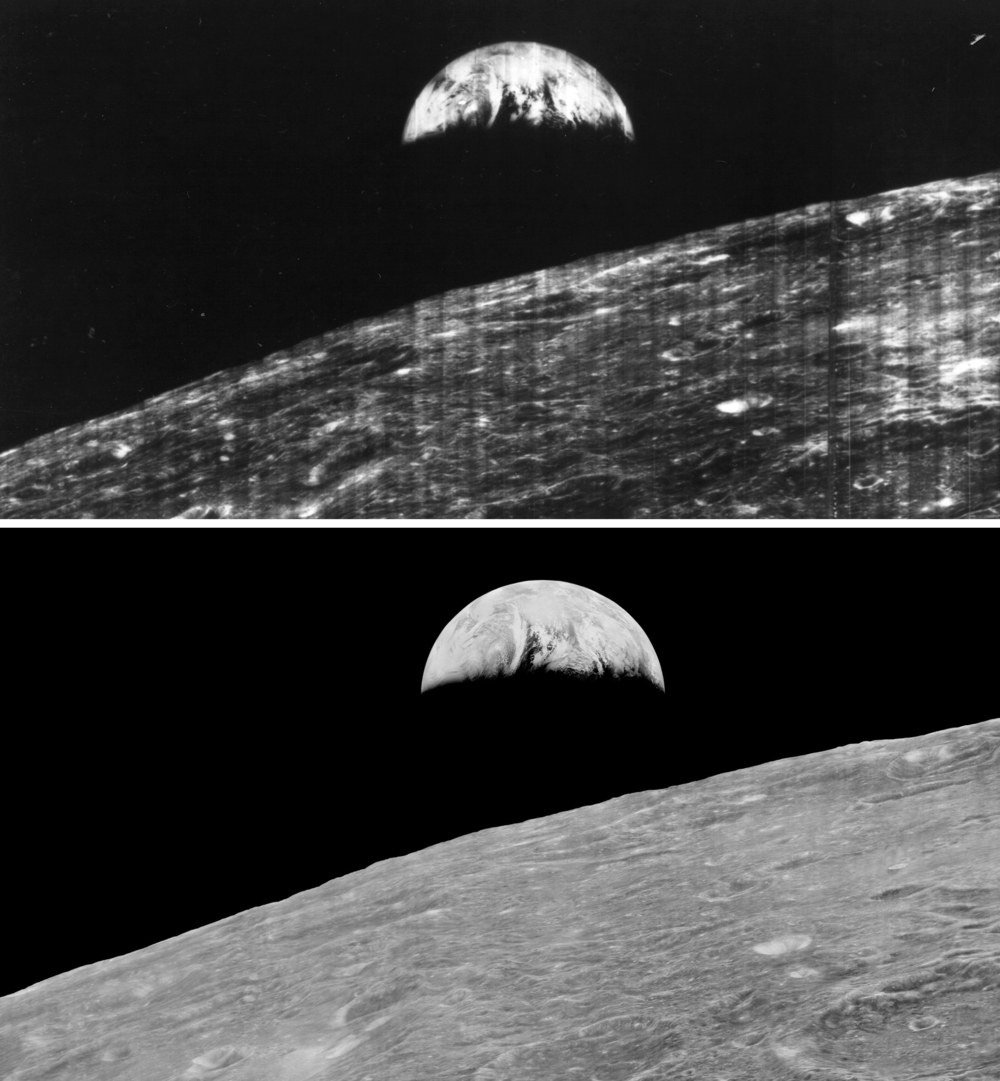

In 1966 and 1967, NASA sent five spacecraft to orbit the Moon to take high-resolution photos to aid in finding a good landing spot for the Apollo missions. NASA released some photos to the public and they were extremely grainy and low resolution because they didn’t want the Soviet Union to know the capabilities of US spy satellites. Here’s a comparison to what the public saw at the time versus how the photos actually looked:

The Lunar Orbiters never returned to Earth with the imagery. Instead, the Orbiter developed the 70mm film (yes film) and then raster scanned the negatives with a 5 micron spot (200 lines/mm resolution) and beamed the data back to Earth using lossless analog compression, which was yet to actually be patented by anyone. Three ground stations on earth, one of which was in Madrid, another in Australia and the other in California recieved the signals and recorded them. The transmissions were recorded on to magnetic tape. The tapes needed Ampex FR-900 drives to read them, a refrigerator sized device that cost $300,000 to buy new in the 1960’s.

The high-res photos were only revealed in 2008, after a volunteer restoration effort undertaken in an abandoned McDonald’s nicknamed McMoon.

They were huge files, even by today’s standards. One of the later images can be as big as 2GB on a modern PC, with photos on top resolution DSLRs only being in the region of 10MB you can see how big these images are. One engineer said you could blow the images up to the size of a billboard without losing any quality. When the initial NASA engineers printed off these images, they had to hang them in a church because they were so big. The below images show some idea of the scale of these images. Each individual image when printed out was 1.58m by 0.4m.

You can view a collection of some of the images here.

Using imagery and data that the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter spacecraft has collected since 2009, NASA made this video tour of the Moon in 4K resolution. This looked incredible on my iMac screen.

As the visualization moves around the near side, far side, north and south poles, we highlight interesting features, sites, and information gathered on the lunar terrain.

See also The 100-megapixel Moon and A full rotation of the Moon.

Wylie Overstreet and Alex Gorosh took a telescope around the streets of LA and invited people to look at the Moon through it. Watching people’s reactions to seeing such a closeup view of the Moon with their own eyes, perhaps for the first time, is really amazing.

Whoa, that looks like that’s right down the street, man!

I often wonder what the effect is of most Americans not being able to see the night sky on a regular basis. As Sriram Murali says:

The night skies remind us of our place in the Universe. Imagine if we lived under skies full of stars. That reminder we are a tiny part of this cosmos, the awe and a special connection with this remarkable world would make us much better beings — more thoughtful, inquisitive, empathetic, kind and caring. Imagine kids growing up passionate about astronomy looking for answers and how advanced humankind would be, how connected and caring we’d feel with one another, how noble and adventurous we’d be.

Seán Doran used images from the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter to create this 100-megapixel image of the Moon (full 10000x10000 pixel image here). Phil Plait explains how Doran made the image:

LRO WAC images have a resolution of about 100 meters per pixel over a swath of about 60 km of lunar surface (using what’s called the pushbroom technique, similar to how a flatbed scanner works). They are usually taken straight down, toward the spacecraft nadir (the opposite of the zenith). To get the correct perspective for the Moon as a globe, Doran took the images, along with altimeter data, and mapped them onto a sphere. That way features near the edge look foreshortened, as they really do when you look at the entire Moon. He also used Apollo images to make sure things lined up. So the image isn’t exactly scientifically rigorous, but it is certainly spectacular.

The image is also available at Gigapan for easier exploration.

Even two months later, I’m still reeling from seeing the total solar eclipse. When I think about that day and those two minutes, a chill goes right down my spine. Vi Hart, who took part in Atlas Obscura’s eclipse festival in Oregon, wrote a beautifully poetic piece about witnessing the eclipse that took me right back there.

I’m not sure exactly what I expected, but this wasn’t it. I’d seen photos of coronas around suns, but this wasn’t that. And I’d expected that those photos, like many astronomical pictures, are long exposure, other wavelengths, and otherwise capturing things the naked eye can’t see. I thought there might be a glow of light in a circle, or nothing, or, I don’t know. What I did not expect was an unholy horror sucking the life and light and warmth out of the universe with long reaching arms, that what I’d seen in pictures was not an exaggeration but a failure to capture the extent of this thing that human eyes, and not cameras, are uniquely suited to absorb the horror of.

I protest the idea that the sun, or the moon, or the hole in the universe where the sun was ripped away from us, was black. It was not black. It was a new color, perceivable to the human eye only in certain conditions. I’ve read the literature on color perception and color philosophy. I’ve got the ontological chops. I feel qualified to make this statement, that this thing in the sky was not black. I could understand why people would describe it as black, just as without a word for red you might describe blood as black. But it wasn’t, and so no photograph could possibly capture what it’s like, and no screen can yet display it.

(thx, geoff)

For a pair of projects, Penelope Umbrico collected hundreds of photos of full Moons from Flickr and arranged them into massive wall-sized collages.

Everyone’s Photos Any License, looks at a purportedly more rarified photographic practice: taking a clear photograph of the full moon requires expensive specialized photographic equipment. However, when I searched Flickr for ‘full moon’ I was surprised to find 1,146,034 nearly identical, technically proficient images, most with the ‘All Rights Reserved’ license. Seen individually any one of these images is impressive. Seen as a group, however, they seem to cancel each other out. Everyone’s Photos Any License seeks to address the shifts in meaning and value that occur when the individual subjective experience of witnessing and photographing is revealed as a collective practice, seen recontextualized in its entirety.

For one of the project, Umbrico requested permission to display “Rights Reserved” photos from 654 photographers in exchange for 1/654 of the profit from any potential sale. Many of them were not into that arrangement, so she substituted images with Creative Commons licences instead.

See also Umbrico’s Sunset Portraits, Suns from Sunsets from Flickr, and TVs from Craigslist. (via austin kleon)

The Moon 1968-1972 is a slim volume of photographs from the Apollo missions to the Moon that took place over four short years almost 50 years ago. The book contains a passage by E.B. White taken from this New Yorker article about the Apollo 11 landing in 1969.

The moon, it turns out, is a great place for men. One-sixth gravity must be a lot of fun, and when Armstrong and Aldrin went into their bouncy little dance, like two happy children, it was a moment not only of triumph but of gaiety. The moon, on the other hand, is a poor place for flags. Ours looked stiff and awkward, trying to float on the breeze that does not blow. (There must be a lesson here somewhere.) It is traditional, of course, for explorers to plant the flag, but it struck us, as we watched with awe and admiration and pride, that our two fellows were universal men, not national men, and should have been equipped accordingly. Like every great river and every great sea, the moon belongs to none and belongs to all. It still holds the key to madness, still controls the tides that lap on shores everywhere, still guards the lovers who kiss in every land under no banner but the sky. What a pity that in our moment of triumph we did not forswear the familiar Iwo Jima scene and plant instead a device acceptable to all: a limp white handkerchief, perhaps, symbol of the common cold, which, like the moon, affects us all, unites us all.

I was not prepared for how incredible the total eclipse was. It was, literally, awesome. Almost a spiritual experience. I also did not anticipate the crazy-ass, reverse storm-chasing car ride we’d need to undertake in order to see it.

I’m not a bucket list sort of person, but ever since seeing a partial eclipse back in college in the 90s (probably this one), I have wanted to witness a total solar eclipse with my own eyes. I started planning for the 2017 event three years ago…the original idea was to go to Oregon, but then some college friends suggested meeting up in Nebraska, which seemed ideal: perhaps less traffic than Oregon, better weather, and more ways to drive in case of poor weather.

Well, two of those things were true. Waking up on Monday, the cloud cover report for Lincoln didn’t look so promising. Rejecting the promise of slightly better skies to the west along I-80, we opted instead to head southeast towards St. Joseph, Missouri where the cloud cover report looked much better. Along the way, thunderstorms started popping up right where we were headed. Committed to our route and trusting this rando internet weather report with religious conviction, we pressed on. We drove through three rainstorms, our car hydroplaning because it was raining so hard, flood warnings popping up on our phones for tiny towns we were about to drive through. Morale was low and the car was pretty quiet for awhile; I Stoically resigned myself to missing the eclipse.

But on the radar, hope. The storms were headed off to the northeast and it appeared as though we might make it past them in time. The Sun appeared briefly through the clouds and from the passenger seat, I stabbed at it shining through the windshield, “There it is! There’s the Sun!” We angled back to the west slightly and, after 3.5 hours in the car, we pulled off the road near the aptly named town of Rayville with 40 minutes until totality, mostly clear skies above us. After our effort, all that was missing was a majestic choral “ahhhhhh” sound as the storm clouds parted to reveal the Sun.

My friend Mouser got his camera set up — he’d brought along the 500mm telephoto lens he uses for birding — and we spent some time looking at the partial eclipse through our glasses, binoculars (outfitted with my homemade solar filter), and phone cameras. I hadn’t seen a partial eclipse since that one back in the 90s, and it was cool seeing the Sun appear as a crescent in the sky. I took this photo through the clouds:

Some more substantial clouds were approaching but not quickly enough to ruin the eclipse. I pumped my fist, incredulous and thrilled that our effort was going to pay off. As totality approached, the sky got darker, our shadows sharpened, insects started making noise, and disoriented birds quieted. The air cooled and it even started to get a little foggy because of the rapid temperature change.

We saw the Baily’s beads and the diamond ring effect. And then…sorry, words are insufficient here. When the Moon finally slipped completely in front of the Sun and the sky went dark, I don’t even know how to describe it. The world stopped and time with it. During totality, Mouser took the photo at the top of the page. I’d seen photos like that before but had assumed that the beautifully wispy corona had been enhanced with filters in Photoshop. But no…that is actually what it looks like in the sky when viewing it with the naked eye (albeit smaller). Hands down, it was the most incredible natural event I’ve ever seen.

After two minutes — or was it several hours? — it was over and we struggled to talk to each other about what we had just seen. We stumbled around, dazed. I felt high, euphoric. Raza Syed put it perfectly:

It was beautiful and dramatic and overwhelming — the most thrillingly disorienting passage of time I’ve experienced since that one time I skydived. It was a complete circadian mindfuck.

After waiting for more than 20 years, I’m so glad I finally got to witness a total solar eclipse in person. What a thing. What a wondrous thing.

Update: Here are some reports from my eclipse-chasing buddies: a photo of Mouser setting up his camera rig, Nina’s sharp shadow at 99% totality, and Mouser’s slightly out-of-focus shot of the Sun at totality (with an account of our travels that day).

Newer posts

Older posts

Socials & More