kottke.org posts about usa

Data from Facebook reveals how the United States is split up into different regions like Stayathomia, Greater Texas, Dixie, and Mormonia.

Stretching from New York to Minnesota, [Stayathomia’s] defining feature is how near most people are to their friends, implying they don’t move far. In most cases outside the largest cities, the most common connections are with immediately neighboring cities, and even New York only has one really long-range link in its top 10. Apart from Los Angeles, all of its strong ties are comparatively local.

(thx, dinu)

Seven myths about the history of the American Revolutionary War, including “Great Britain Could Never Have Won The War” and “General Washington Was A Brilliant Tactician And Strategist”.

Washington also failed to see the potential of a campaign against the British in Virginia in 1780 and 1781, prompting Comte de Rochambeau, commander of the French Army in America, to write despairingly that the American general “did not conceive the affair of the south to be such urgency.” Indeed, Rochambeau, who took action without Washington’s knowledge, conceived the Virginia campaign that resulted in the war’s decisive encounter, the siege of Yorktown in the autumn of 1781.

The eggs for the swine flu vaccine are produced by dozens of farms classified by the US government as part of our country’s “critical infrastructure”.

To ensure it had enough eggs to meet pandemic-level demand, the government invested more than $44 million in the program over five years; more than 35 farms are now involved in this feathered Manhattan Project. No signs advertise the farms’ involvement in the program, and visits from the outside world are discouraged. The government won’t disclose where the farms are located, and the farmers are told to keep quiet about their work — not even the neighbors are to know.

These don’t exactly sound like free-range operations:

After nine months of service, [the chickens] are typically euthanized because they can no longer lay “optimal eggs,” Mr. Robinson said. “They’ve served their government,” he said.

(thx, micah)

Twilight of the American newspaper tells the story of San Francisco and its newspapers. And in that tale, a glimpse that we might be losing our sense of place along with the newspaper.

We will end up with one and a half cities in America — Washington, D.C., and American Idol. We will all live in Washington, D.C., where the conversation is a droning, never advancing, debate between “conservatives” and “liberals.” We will not read about newlyweds. We will not read about the death of salesmen. We will not read about prize Holsteins or new novels. We are a nation dismantling the structures of intellectual property and all critical apparatus. We are without professional book reviewers and art critics and essays about what it might mean that our local newspaper has died. We are a nation of Amazon reader responses (Moby Dick is “not a really good piece of fiction” — Feb. 14, 2009, by Donald J. Bingle, Saint Charles, Ill. — two stars out of five). We are without obituaries, but the famous will achieve immortality by a Wikipedia entry.

This clever graph by National Geographic shows the cost of healthcare compared to life expectancy in a number of countries. The way that the US healthcare expenditure is pictured entirely outside the confines of the graph’s scale and legend is a particularly effective design decision. (thx, jim)

Loosely based on Howard Zinn’s A People’s History of the United States, The People Speak is a show that features well-known actors reading famous speeches and letters from American history.

Using dramatic and musical performances of the letters, diaries and speeches of everyday Americans, The People Speak gives voice to those who spoke up for social change throughout U.S. history, forging a nation from the bottom up with their insistence on equality and justice.

The show starts airing this Sunday but many of the performances are already available online.

New-ish thing from fake is the new real: outlines of the 100 most populous areas in the US. Some are cities and some are states.

The fifty largest metro areas (in blue), disaggregated from their states (in orange). Each has been scaled and sorted according to population.

By themselves, the New York, Los Angeles, and Chicago metros are the three most populous areas in the US. (via snarkmarket)

Maira Kalman wonders about the patterns of food consumption in the United States, whether it is democratic or not, and how we might want to change.

Every one of her essays is outstanding; I can’t stop linking to them.

The most striking feature of the H1N1 flu vaccine manufacturing process is the 1,200,000,000 chicken eggs required to make the 3 billion doses of vaccine that may be required worldwide. There are entire chicken farms in the US and around the world dedicated to producing eggs for the purpose of incubating influenza viruses for use in vaccines. No wonder it takes six months from start to finish. But we’ll get to that in a minute.

The most commonly used process for manufacturing an influenza vaccine was developed in the 1940s — one of its co-inventors was Jonas Salk, who would go on to develop the polio vaccine — and has remained basically unchanged since then. The process is coordinated by the World Health Organization and begins with the detection of a new virus (or rather one that differs significantly from those already going around); in this instance, the Pandemic H1N1/09 virus. Once the pandemic strain has been identified and isolated, it is mixed with a standard laboratory virus through a technique called genetic reassortment, the purpose of which is to create a hybrid virus (also called the “reference virus strain”) with the pandemic strain’s surface antigens and the lab strain’s core components (which allows the virus to grow really well in chicken eggs). Then the hybrid is tested to make sure that it grows well, is safe, and produces the proper antigen response. This takes about six to nine weeks.

[Quick definitional pause. Antigen: “An antigen is any substance that causes your immune system to produce antibodies against it. An antigen may be a foreign substance from the environment such as chemicals, bacteria, viruses, or pollen. An antigen may also be formed within the body, as with bacterial toxins or tissue cells.” So, when the H1N1 vaccine gets inside your body, the pandemic strain’s surface antigens will produce antibodies against it.]

At roughly the same time, a parallel effort to produce what are referred to as reference reagents is undertaken. The deliverable here is a standardized kit provided to vaccine manufacturers so that they can test how much virus they are making and how effective it is. This process serves to standardize vaccine doses across manufacturers and takes four months to complete. WHO notes that this part of the process is “often a bottleneck to the overall timeline for manufacturers to generate the vaccine”.

Once the reference virus strain is produced, it is sent to pharmaceutical companies (Novartis, Sanofi Pasteur, etc.) for large-scale production of the vaccine. The companies fine-tune the virus to increase yields and produce seed virus banks that will be used in the bulk production.

And this is where the 1.2 billion chicken eggs come in. A portion of the seed virus is injected into each 9- to 12-day old fertilized egg. The virus incubates in the egg white for two to three days and is then separated from the egg.

For the shot vaccine, the virus is sterilized so that it won’t make anyone sick. This is the magic part of the vaccine: it’s got the pandemic virus antigens that make your body produce the antibodies to fight the virus but the virus is inactive so it won’t make you ill. For the nasal spray vaccine, the virus is left alive and attenuated to survive only in the nose and not the warmer lungs; it’ll infect you enough to produce antibodies but not enough to make you sick. Either way, the surface antigens are separated out and purified to produce the active ingredient in the vaccine. Each batch of antigen takes about two weeks to produce. With enough laboratory space and chicken eggs, the companies can crank out an infinite amount of purified antigens, but those resources are limited in practice.

[Side note. You may have noticed that the H1N1 vaccine has been difficult to find in some places around the US. The vaccine manufacturers have said that the Pandemic H1N1/09 virus when combined with the standard laboratory virus does not grow as fast in the eggs as they anticipated. The batches of antigens from each egg have been smaller than expected, up to five or even ten times smaller in some cases. Hence the slow rollout of the vaccine.]

The purified antigen is then tested against the aforementioned reference reagents once they are ready. The antigen is diluted to the required concentration and placed into properly labelled vials or syringes. Further testing is performed to make sure the vaccine won’t make anyone ill, to confirm the correct concentration, and for general safety. At this point clinical testing in humans is required in western Europe but not in the United States. Finally, each company’s vaccine has to be approved by the appropriate regulatory body in each country — that’s the FDA in the case of the US — and then the vaccine is distributed to medical facilities around the country.

Sources and more information: WHO, WHO, WHO, WHO, CDC, Time, Washington Post, The Big Picture, Influenza Report, NPR, Wikipedia, Wikipedia, Wikipedia, Wikipedia.

Update: Included in a recent 60 Minutes segment on the H1N1 vaccine is a look at the manufacturing process. (thx, @briandigital)

How did the Byzantine Empire stay around so long? A look at the answers might hold some lessons for the present-day United States.

Avoid war by every possible means, in all possible circumstances, but always act as if war might start at any time. Train intensively and be ready for battle at all times — but do not be eager to fight. The highest purpose of combat readiness is to reduce the probability of having to fight.

In the US, when you make under $20,000, there are government subsidies available to help you out. Between $20-40,000 per year, those subsidies are less available, which makes it difficult for people to cross the gap between one and the other.

In fact, until you get past $40,000 a year, any raise or higher paying job you get might actually sink you deeper into poverty.

(via migurski)

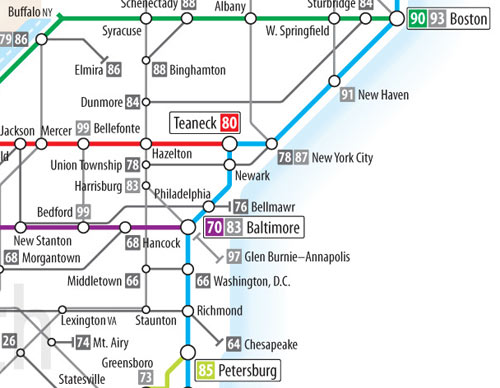

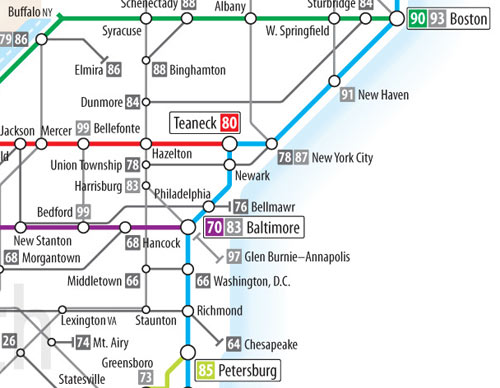

Map of the US Interstate system in the style of the London Tube map.

Go large for detail. (via coudal)

In the early days of the United States (and even in the colonial days), there were struggles about how to handle healthcare. Was it the responsibility of the federal government, the state government, or the individual?

Health care in Colonial America looked nothing like what we’d consider medicine today, but the debates it triggered were similar. The danger of smallpox and the high cost of its prevention led to divisive questions about who should pay, whether everyone deserved equal access, and if responsibility lay at the feet of the individual, the state, or the nation. Epidemics forced the early republic to wrestle with the question of the federal government’s proper role in regulating the nation’s health.

A recent blog post by Roger Ebert shows that more than 200 years later, we’re still having this same basic argument.

I am told we cannot trust the government. I believe we must trust it, and work to make it trustworthy. We are told the free enterprise system will sort things out, but it has not. When insurance companies direct millions toward lobbying and advertising against a health care system, every dollar is being withheld from sick people. When it goes to salaries, executive jets, corporate edifices and legislative manipulation, it isn’t going to Amy Caudle.

Rich Cohen has a really fantastic article about the American history of the automobile and car salesman in the September issue of The Believer.

The history of America is the history of the automobile industry: it starts in fields and garages and ends in boardrooms and dumps; it starts with daredevils and tinkerers and ends with bureaucrats and congressmen; it starts with a sense of here-goes-let’s-hope-it-works and ends with help-help-help. We tend to think of it as an American history that opens, as if summoned by the nature of the age, early in the last century, when the big mills and factories were already spewing smoke above Flint and Detroit, but we tend to be wrong. The history of the car is far older and stranger than you might suppose. Its early life is like the knock-around life one of the stars of the ’80s lived in the ’70s, Stallone before Rocky, say, picking up odd jobs, working the grift, and, of course, porn. The first automobile turned up outside Paris in 1789, when Detroit was an open field. (The hot rod belonged to the Grand Armee before it belonged to Neal and Jack.) It was another of the great innovations that seemed to appear in that age of revolution.

Cohen references one of my favorite pieces from a few years ago, Confessions of a Car Salesman, in which a journalist goes undercover for three months at a pair of Southern California car dealerships. Required reading before purchasing a car.

Cohen’s article also reminded me just how many of the American cars on the road today owe their names to the people who actually started these companies and built these cars back in the early days. Ransom Olds, Louis Chevrolet, Walter Chrysler, Horace and John Dodge, Henry Ford, David Buick…some of these read like a joke from The Simpsons. Here’s Louis Chevrolet racing a Buick in 1910:

Looking overseas, there’s Karl Benz, Michio Suzuki (who didn’t actually start out building cars), Wilhelm Maybach, Ferdinand Porsche, and many others. In an interesting reversal of that trend, Daimler Motoren Gesellschaft (which eventually became part of Daimler-Benz) built a custom sports car for Emil Jellinek, who named it Mercedes after his daughter. Jellinek was so fond of the car that he legally changed his last name to Jellinek-Mercedes and thereafter went by E.J. Mercédès.

To get to a McDonald’s in the lower 48 United States, it’s never more than 145 miles by car. And the McFarthest Spot in the US is in South Dakota.

For maximum McSparseness, we look westward, towards the deepest, darkest holes in our map: the barren deserts of central Nevada, the arid hills of southeastern Oregon, the rugged wilderness of Idaho’s Salmon River Mountains, and the conspicuous well of blackness on the high plains of northwestern South Dakota.

See also maximum Starbucks density and Starbucks center of gravity of Manhattan.

Update: The distribution of McDonald’s in Australia is a bit more uneven. (thx, kit)

Update: As of December 2018, the point the farthest away from any McDonald’s in the lower 48 US states is in Nevada, 120 miles away from the nearest McDonald’s.

What I Learned Today has an excerpt from an article by William Falk of The Week (not online) that suggests, tongue in cheek (I think), that the red parts of the USA should secede from the blue USA.

In a new nation fashioned out of the current red states — call it, for the sake of argument, Limbaughland — the federal tax rate would be cut to 10%, Medicaid, Medicare, and Social Security would be abolished, abortion would be illegal, gays would be closeted again, and Christianity would be the official state religion. Anyone could buy any kind of gun, no questions asked. In the current blue states, which we will call ObamaNation, the federal tax rate would top out at 90%; all employers would institute quota systems for minorities, women and less-abled persons; and you’d get your health care form a single-payer system like Canada’s. Fast food and guns would be banned, while gay marriage and marijuana would be legal.

Tyler Cowen takes a crack at defining American conservatism.

Fiscal conservatism is part and parcel of conservatism per se. A state wrecked by debt is a state due to perish or fall into decay. This is a lesson from history. States must “save up their powder” for true crises and it is a kind of narcissistic arrogation to think that the personal failures of particular individuals — often those with weak values — meet this standard.

Cowen did the same for progressivism a few weeks ago.

Progressive policies offer more scope for individualism and some kinds of freedom. Greater security gives people a greater chance to develop themselves as individuals in important spheres of life, not just money-making and risk protection and winning relative status games.

Atul Gawande and some colleagues searched the US for healthcare successes — hospitals and clinics where costs are relatively low and quality of care is high — and came up with a few lessons.

If the rest of America could achieve the performances of regions like these, our health care cost crisis would be over. Their quality scores are well above average. Yet they spend more than $1,500 (16 percent) less per Medicare patient than the national average and have a slower real annual growth rate (3 percent versus 3.5 percent nationwide).

I wanted this article to be much longer than it was with breakouts of each of the ten lessons with lengthy explanations.

In a week-long series for Slate, Josh Levin asks: how is America going to end?

Hurricane Katrina proved that modern America is resilient. It didn’t prove that we’ll be around forever. After watching the place where I grew up avert total annihilation, I can’t help but wonder what course of events will eventually wipe out New Orleans and America as a whole. When it comes to human civilization, entropy conquers all: Rome fell, the Aztecs were conquered, the British Empire withered, and the Soviet Union cracked apart. America may be exceptional, but it’s not supernatural. Our noble experiment, like every other before it, has to end sometime.

Can you put a dollar value on a human life? Peter Singer writes that the US needs to do just that if we’re serious about making our healthcare system work.

You have advanced kidney cancer. It will kill you, probably in the next year or two. A drug called Sutent slows the spread of the cancer and may give you an extra six months, but at a cost of $54,000. Is a few more months worth that much?

If you can afford it, you probably would pay that much, or more, to live longer, even if your quality of life wasn’t going to be good. But suppose it’s not you with the cancer but a stranger covered by your health-insurance fund. If the insurer provides this man - and everyone else like him - with Sutent, your premiums will increase. Do you still think the drug is a good value? Suppose the treatment cost a million dollars. Would it be worth it then? Ten million? Is there any limit to how much you would want your insurer to pay for a drug that adds six months to someone’s life? If there is any point at which you say, “No, an extra six months isn’t worth that much,” then you think that health care should be rationed.

In an attempt to answer that question, Elizabeth Kolbert reviews a gaggle of books in this week’s New Yorker. (This is only part of the answer.)

According to what’s known as the Expensive Tissue Hypothesis, early humans compensated for the energy used in their heads by cutting back on the energy used in their guts; as man’s cranium grew, his digestive tract shrank. This forced him to obtain more energy-dense foods than his fellow-primates were subsisting on, which put a premium on adding further brain power. The result of this self-reinforcing process was a strong taste for foods that are high in calories and easy to digest; just as it is natural for gorillas to love leaves, it is natural for people to love funnel cakes.

Kolbert’s article is a good overview of the current popular views on obesity. Related: Scientists Discover Gene Responsible For Eating Whole Goddamn Bag Of Chips.

I’ve got two follow-ups to share with you regarding Atul Gawande’s New Yorker piece about healthcare costs in the US (kottke.org post). In the Wall Street Journal, Abraham Verghese argues that in order for a healthcare reform plan to be successful, it has to include cost cutting.

I recently came on a phrase in an article in the journal “Annals of Internal Medicine” about an axiom of medical economics: a dollar spent on medical care is a dollar of income for someone. I have been reciting this as a mantra ever since. It may be the single most important fact about health care in America that you or I need to know. It means that all of us — doctors, hospitals, pharmacists, drug companies, nurses, home health agencies, and so many others — are drinking at the same trough which happens to hold $2.1 trillion, or 16% of our GDP. Every group who feeds at this trough has its lobbyists and has made contributions to Congressional campaigns to try to keep their spot and their share of the grub. Why not? — it’s hog heaven. But reform cannot happen without cutting costs, without turning people away from the trough and having them eat less. If you do that, you have to be prepared for the buzz saw of protest that dissuaded Roosevelt, defeated Truman’s plan and scuttled Hillary Clinton’s proposal.

In Gawande’s example, what Verghese is saying is that you can’t just make McAllen’s healthcare system adopt an El Paso type of system without a whole lot of pain.

Gawande addressed some of the criticisms of his article on the New Yorker site. One of the major criticisms was that McAllen’s higher costs were associated with higher levels of poverty and unhealthiness:

As I noted in the piece, McAllen is indeed in the poorest county in the country, with a relatively unhealthy population and the problems of being a border city. They have a very low physician supply. The struggles the people and medical community face there are huge. But they are just as huge in El Paso — its residents are barely less poor or unhealthy or under-supplied with physicians than McAllen, and certainly not enough so to account for the enormous cost differences. The population in McAllen also has more hospital beds than four out of five American cities.

Atul Gawande discovered that McAllen, Texas spends more per person on healthcare than El Paso (which is demographically similar to McAllen) and set out to find out why. Along the way, he encounters a curious relationship between the amount spent on healthcare and the quality of that care: higher spending does not correlate with better care.

When you look across the spectrum from Grand Junction to McAllen — and the almost threefold difference in the costs of care — you come to realize that we are witnessing a battle for the soul of American medicine. Somewhere in the United States at this moment, a patient with chest pain, or a tumor, or a cough is seeing a doctor. And the damning question we have to ask is whether the doctor is set up to meet the needs of the patient, first and foremost, or to maximize revenue.

There is no insurance system that will make the two aims match perfectly. But having a system that does so much to misalign them has proved disastrous. As economists have often pointed out, we pay doctors for quantity, not quality. As they point out less often, we also pay them as individuals, rather than as members of a team working together for their patients. Both practices have made for serious problems.

Obama, you’re reading this guy’s stuff, yes? Get him on the team.

Update: Dr. Peter Orszag is the Director of the Office of Management and Budget for the White House and is working on some of the problems that Gawande talks about in this article. Here’s a 40-minute video of Orszag speaking on “Health Care - Capturing the Opportunity in the Nation’s Core Fiscal Challenge”. (thx, todd)

I changed the bit in the first paragraph about El Paso and McAllen being “nearby”. Funny, I thought 800 miles in Texas *was* nearby. (thx, stephen)

I also changed “lower spending correlates with better care” to “higher spending does not correlate with better care”…those two statements are not the same. I misread the results of one of the studies that Gawande mentions. (thx, patrick)

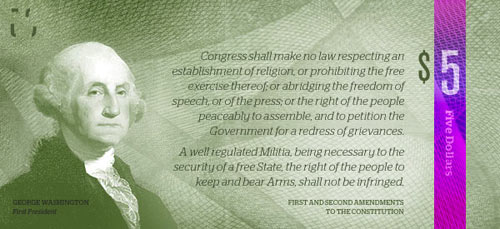

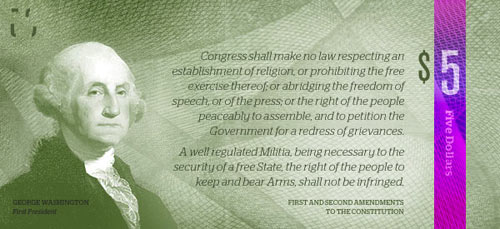

Richard Smith is hosting the Dollar Redesign Project, which is starting to attract some interesting redesigns of American paper currency.

Ministry of Type has some further analysis, including a comparison to European bills.

Georg Jensen aruges that the USPS has, in effect, turned into a huge mail spamming operation (among other problematic aspects of the organization).

Just as General Motors has in effect subsidized Big Oil by continuing to build gas-guzzlers in recent years, so has the USPS continued to subsidize Big Mail by shaping its operations to encourage what it now calls, revealingly, “standard mail” — that is, advertising junk mail. Most American citizens are blissfully unaware of the degree to which USPS subsidizes U.S. businesses by means of the fees it collects from ordinary postal customers. For example, if you wish to mail someone a large envelope weighing three ounces, you’ll pay $1.17 in postage. A business can bulk-mail a three-ounce catalog of the same size for as little as $0.14.

Atul Gawande branches out from his usual excellent writing on medicine and turns his attention to solitary confinement in America’s prison system. Gawande likens extended solitary time to torture.

This is the dark side of American exceptionalism. With little concern or demurral, we have consigned tens of thousands of our own citizens to conditions that horrified our highest court a century ago. Our willingness to discard these standards for American prisoners made it easy to discard the Geneva Conventions prohibiting similar treatment of foreign prisoners of war, to the detriment of America’s moral stature in the world. In much the same way that a previous generation of Americans countenanced legalized segregation, ours has countenanced legalized torture. And there is no clearer manifestation of this than our routine use of solitary confinement-on our own people, in our own communities, in a supermax prison, for example, that is a thirty-minute drive from my door.

This likely will not change until Americans start to believe that rehabilitation and not punishment is the primary goal of prisons. So, probably never.

The results of a survey commissioned by the California Academy of Sciences reveals that Americans don’t know a whole lot about science.

- Only 53% of adults know how long it takes for the Earth to revolve around the Sun.

- Only 59% of adults know that the earliest humans and dinosaurs did not live at the same time.

- Only 47% of adults can roughly approximate the percent of the Earth’s surface that is covered with water.*

- Only 21% of adults answered all three questions correctly.

I bet this got cumulatively 10 seconds of coverage on the major “news” networks, if that. Compare with the endless airtime given to this AIG business and then pull your hair out until you resemble Bruce Willis. (via clusterflock)

Pew Research Center’s interactive maps of migration flows in the US are pretty interesting. The region map makes it seem as though the Northeast is rapidly losing population to the South but the states map clarifies the picture…the flow looks to be hundreds of thousands of retirees moving to Florida and Georgia.

Some think it’s unfair that the former president of Countrywide Financial, a mortgage company that played a big (and negative) role in the subprime mortgage debacle, is now the head of a company making big money buying troubled mortgages from the US government for cheap and then refinancing with the owner, making big money in the process.

But as a Baltimorean explains to McNutty in the very first scene of the first episode of The Wire, that’s how America works.

McNulty: Let me understand. Every Friday night, you and your boys are shootin’ craps, right? And every Friday night, your pal Snot Boogie… he’d wait til there’s cash on the ground and he’d grab it and run away? You let him do that?

Suspect: We’d catch him and beat his ass but ain’t nobody ever go past that.

McNulty: I’ve gotta ask you: if every time Snot Boogie would grab the money and run away… why’d you even let him in the game?

(thx, aaron)

Newer posts

Older posts

Stay Connected