The Backyard Astronomer

With the homemade telescope in his backyard observatory, amateur astronomer Gary Hug has discovered over 300 asteroids.

This site is made possible by member support. ❤️

Big thanks to Arcustech for hosting the site and offering amazing tech support.

When you buy through links on kottke.org, I may earn an affiliate commission. Thanks for supporting the site!

kottke.org. home of fine hypertext products since 1998.

With the homemade telescope in his backyard observatory, amateur astronomer Gary Hug has discovered over 300 asteroids.

I’ve pretty much stopped watching science and engineering TV shows because their information density is often so low. Mythbusters is no exception, but this clever YouTube channel helpfully edits the 44-minute episodes down to a svelte and info-packed 2-5 minutes. (via digg)

With amazing super slow-motion footage of a match head starting to burn as a backdrop, this video explains the chemical reactions involved in lighting a match.

When the match is struck, a small amount of the red phosphorus on the striking surface is converted into white phosphorus, which then ignites. The heat from this ignites the potassium chlorate, and the match head bursts into flame. During manufacture, the match stick itself is soaked in ammonium phosphate, which prevents ‘afterglow’ once the flame has gone out, and paraffin, which ensures that it burns easily.

(via gizmodo)

In an all-white room, mosquitoes are mated and the resulting larvae divided by sex. Workers whisk at stray mosquitoes with electrified tennis rackets — the kind you see in novelty stores, but which have sold out in mosquito-obsessed Brazil.

MIT Tech Review takes you inside the mosquito factory that could stop Zika and other diseases. (Add “working in a mosquito factory” to the list of jobs I’m glad I don’t have…)

From PHD Comics, and explanation of what gravitational waves are and why their discovery is so important to the future of science. (via df)

Update: Brian Greene’s explanation of gravitational waves to Stephen Colbert is the best one yet:

Greene is great at explaining physics in terms almost anyone can understand. Even though it’s more than 15 years old now, his book, The Elegant Universe, still contains the best explanation of modern physics (quantum mechanics + relativity) I’ve ever read.

In How We Got to Now, the TV series based on the book of the same name, Steven Johnson explains how the wine press was used to print books, which resulted in a surge in demand for reading glasses, which had yet more unintended effects.

Johnson calls this cascade of inadvertent invention the Hummingbird Effect.

This is how change happens in the natural world: sometime during the Cretaceous age, flowers began to evolve colors and scents that signaled the presence of pollen to insects, who simultaneously evolved complex equipment to extract the pollen and, inadvertently, fertilize other flowers with pollen.

Over time, the flowers supplemented the pollen with even more energy-rich nectar to lure the insects into the rituals of pollination. Bees and other insects evolved the sensory tools to see and be drawn to flowers, just as the flowers evolved the properties that attract bees. The symbiosis between flowering plants and insects that led to the production of nectar ultimately created an opportunity for much larger organisms — the hummingbirds — to extract nectar from plants, though to do that they evolved a extremely unusual form of flight mechanics that enable them to hover alongside the flower in a way that few birds can even come close to doing. In other words, they had to learn an entirely new way to fly.

In an interview with Popular Mechanics, Johnson shared another example:

At the start of the 20th century, in Brooklyn, a printer was doing full-color magazines. In the summer the ink didn’t set up properly. The printer hired a young engineer, Willis Carrier, to devise a way to bring down the temperature and humidity in the room. He built this contraption that made the printing possible. Then the workers were like, “I’m gonna have my lunch in the room with the contraption, it’s cool in there.” Carrier says, “Hmm, that’s interesting.” He sets up the Carrier Corporation, which air-conditions movie theaters, paving the way for the summer blockbuster. Before air conditioning, a crowded theater was the last place you wanted to go. After a/c, summer movies become part of the cultural landscape.

After a potential detection of gravitational waves back in 2014 turned out to be galactic dust, scientists working on the LIGO experiment have announced they have finally detected evidence of gravitational waves. Nicola Twilley has the scoop for the New Yorker on how scientists detected the waves.

A hundred years ago, Albert Einstein, one of the more advanced members of the species, predicted the waves’ existence, inspiring decades of speculation and fruitless searching. Twenty-two years ago, construction began on an enormous detector, the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO). Then, on September 14, 2015, at just before eleven in the morning, Central European Time, the waves reached Earth. Marco Drago, a thirty-two-year-old Italian postdoctoral student and a member of the LIGO Scientific Collaboration, was the first person to notice them. He was sitting in front of his computer at the Albert Einstein Institute, in Hannover, Germany, viewing the LIGO data remotely. The waves appeared on his screen as a compressed squiggle, but the most exquisite ears in the universe, attuned to vibrations of less than a trillionth of an inch, would have heard what astronomers call a chirp — a faint whooping from low to high. This morning, in a press conference in Washington, D.C., the LIGO team announced that the signal constitutes the first direct observation of gravitational waves.

The NY Times headline above is from when the concept of gravitational lensing suggested by Einstein’s theory of relatively was confirmed in 1919. I thought it was appropriate in this case. Wish they still ran headlines like that.

Update: The LIGO team has detected gravitational waves a second time.

Today, the LIGO team announced its second detection of gravitational waves-the flexing of space and time caused by the black hole collision. The waves first hit the observatory in Livingston, Louisiana, and then 1.1 milliseconds later passed through the one in Hanford, Washington.

By now, those waves are 2.8 trillion or so miles away, momentarily reshaping every bit of space they pass through.

For her new book, Ariel Waldman asked dozens of astronauts about their experiences in space.

With playful artwork accompanying each, here are the real stories behind backwards dreams, “moon face,” the tricks of sleeping in zero gravity and aiming your sneeze during a spacewalk, the importance of packing hot sauce, and dozens of other cosmic quirks and amazements that come with travel in and beyond low Earth orbit.

Waldman is the co-creator of the very cool spaceprob.es.

Update: This book is now out, shipping, released…launched, if you will.

“I’m looking at a picture of two mice. The one on the right looks healthy. The one on the left has graying fur, a hunched back, and an eye that’s been whitened by cataracts.”

What’s the difference? Well, scientists at the Mayo clinic used a process to remove senescent (or retired) cells from one of them. And that process leads to mice who age better and live longer. As one researcher not connected to the study explains:

The usual caveats apply — it’s got to be reproduced by other people — but if it’s correct, without wanting to be too hyperbolic, it’s one of the more important aging discoveries ever.

As part of a celebration of the legacy of Richard Feynman at Caltech this week, Bill Gates contributed a video about what he learned from Feynman.

In that video, I especially love the way Feynman explains how fire works. He takes such obvious delight in knowledge — you can see his face light up. And he makes it so clear that anyone can understand it.

I love that video as well…just watched it again and it’s so so good.

So, this is a time travel movie with Keanu Reeves (narrator) and Alex Winter (director), but it’s not Bill & Ted’s Excellent Adventure, Part 3? No, of course not. It’s actually a video about quantum chess featuring Paul Rudd, Stephen Hawking, and music from The Matrix. Like, WHAT?! If The Chickening hadn’t dropped earlier, this would be the oddest thing you’ll watch this week. (And it’s not quite clear, but the video appears to be an advertisement for a quantum chess game that’s launching on Kickstarter next week. Nothing about this makes any sense…) (via @gavinpurcell)

Today is the 30th anniversary of the final launch and subsequent catastrophic loss of the Space Shuttle Challenger. Popular Mechanics has an oral history of the launch and aftermath.

Capano: We got the kids quiet, and then I remember that the line that came across the TV was “The vehicle has exploded.” One of the girls in my classroom said, “Ms. Olson [Capano’s maiden name], what do they mean by ‘the vehicle’?” And I looked at her and I said, “I think they mean the shuttle.” And she got very upset with me. She said, “No! No! No! They don’t mean the shuttle! They don’t mean the shuttle!”

Raymond: The principal came over the PA system and said something like, “We respectfully request that the media leave the building now. Now.” Some of the press left, but some of them took off into the school. They started running into the halls to get pictures, to get sound-people were crying, people were running. It was chaos. Some students started chasing after journalists to physically get them out of the school.

I have certainly read about Feynman’s O-ring demonstration during the investigation of the disaster, but I hadn’t heard this bit:

Kutyna: On STS-51C, which flew a year before, it was 53 degrees [at launch, then the coldest temperature recorded during a shuttle launch] and they completely burned through the first O-ring and charred the second one. One day [early in the investigation] Sally Ride and I were walking together. She was on my right side and was looking straight ahead. She opened up her notebook and with her left hand, still looking straight ahead, gave me a piece of paper. Didn’t say a single word. I look at the piece of paper. It’s a NASA document. It’s got two columns on it. The first column is temperature, the second column is resiliency of O-rings as a function of temperature. It shows that they get stiff when it gets cold. Sally and I were really good buddies. She figured she could trust me to give me that piece of paper and not implicate her or the people at NASA who gave it to her, because they could all get fired.

I wondered how I could introduce this information Sally had given me. So I had Feynman at my house for dinner. I have a 1973 Opel GT, a really cute car. We went out to the garage, and I’m bragging about the car, but he could care less about cars. I had taken the carburetor out. And Feynman said, “What’s this?” And I said, “Oh, just a carburetor. I’m cleaning it.” Then I said, “Professor, these carburetors have O-rings in them. And when it gets cold, they leak. Do you suppose that has anything to do with our situation?” He did not say a word. We finished the night, and the next Tuesday, at the first public meeting, is when he did his O-ring demonstration.

We were sitting in three rows, and there was a section of the shuttle joint, about an inch across, that showed the tang and clevis [the two parts of the joint meant to be sealed by the O-ring]. We passed this section around from person to person. It hit our row and I gave it to Feynman, expecting him to pass it on. But he put it down. He pulled out pliers and a screwdriver and pulled out the section of O-ring from this joint. He put a C-clamp on it and put it in his glass of ice water. So now I know what he’s going to do. It sat there for a while, and now the discussion had moved on from technical stuff into financial things. I saw Feynman’s arm going out to press the button on his microphone. I grabbed his arm and said, “Not now.” Pretty soon his arm started going out again, and I said, “Not now!” We got to a point where it was starting to get technical again, and I said, “Now.” He pushed the button and started the demonstration. He took the C-clamp off and showed the thing does not bounce back when it’s cold. And he said the now-famous words, “I believe that has some significance for our problem.” That night it was all over television and the next morning in the Washington Post and New York Times. The experiment was fantastic-the American public had short attention spans and they didn’t understand technology, but they could understand a simple thing like rubber getting hard.

I never talked with Sally about it later. We both knew what had happened and why it had happened, but we never discussed it. I kept it a secret that she had given me that piece of paper until she died [in 2012].

Whoa, dang. Also not well known is that the astronauts survived the initial explosion and were possibly alive and conscious when they hit the water two and a half minutes later.

Over the December holiday, I read 10:04 by Ben Lerner (quickly, recommended). The novel includes a section on the Challenger disaster and how very few people saw it live:

The thing is, almost nobody saw it live: 1986 was early in the history of cable news, and although CNN carried the launch live, not that many of us just happened to be watching CNN in the middle of a workday, a school day. All other major broadcast stations had cut away before the disaster. They all came back quickly with taped replays, of course. Because of the Teacher in Space Project, NASA had arranged a satellite broadcast of the mission into television sets in many schools — and that’s how I remember seeing it, as does my older brother. I remember tears in Mrs. Greiner’s eyes and the students’ initial incomprehension, some awkward laughter. But neither of us did see it: Randolph Elementary School in Topeka wasn’t part of that broadcast. So unless you were watching CNN or were in one of the special classrooms, you didn’t witness it in the present tense.

Oh, the malleability of memory. I remember seeing it live too, at school. My 7th grade English teacher permanently had a TV in her room and because of the schoolteacher angle of the mission, she had arranged for us to watch the launch, right at the end of class. I remember going to my next class and, as I was the first student to arrive, telling the teacher about the accident. She looked at me in disbelief and then with horror as she realized I was not the sort of kid who made terrible stuff like that up. I don’t remember the rest of the day and now I’m doubting if it happened that way at all. Only our classroom and a couple others watched it live — there wasn’t a specially arranged whole-school event — and I doubt my small school had a satellite dish to receive the special broadcast anyway. Nor would we have had cable to get CNN…I’m not even sure cable TV was available in our rural WI town at that point. So…?

But, I do remember the jokes. The really super offensive jokes. The jokes actually happened. Again, from 10:04:

I want to mention another way information circulated through the country in 1986 around the Challenger disaster, and I think those of you who are more or less my age will know what I’m talking about: jokes. My brother, who is three and a half years older than I, would tell me one after another as we walked to and from Randolph Elementary that winter: Did you know that Christa McAuliffe was blue-eyed? One blew left and one blew right; What were Christa McAuliffe’s last words to her husband? You feed the kids — I’ll feed the fish; What does NASA stand for? Need Another Seven Astronauts; How do they know what shampoo Christa McAuliffe used? They found her head and shoulders. And so on: the jokes seemed to come out of nowhere, or to come from everywhere at once; like cicadas emerging from underground, they were ubiquitous for a couple of months, then disappeared. Folklorists who study what they call ‘joke cycles’ track how — particularly in times of collective anxiety — certain humorous templates get recycled, often among children.

At the time, I remember these jokes being hilarious1 but also a little horrifying. Lerner continues:

The anonymous jokes we were told and retold were our way of dealing with the remainder of the trauma that the elegy cycle initiated by Reagan-Noonan-Magee-Hicks-Dunn-C.A.F.B. (and who knows who else) couldn’t fully integrate into our lives.

Reminds me of how children in Nazi ghettos and concentration camps dealt with their situation by playing inappropriate games.

Even in the extermination camps, the children who were still healthy enough to move around played. In one camp they played a game called “tickling the corpse.” At Auschwitz-Birkenau they dared one another to touch the electric fence. They played “gas chamber,” a game in which they threw rocks into a pit and screamed the sounds of people dying.

Also, does anyone remember the dead baby jokes? They were all the rage when I was a kid. There were books of them. “Q: What do you call a dead baby with no arms and no legs laying on a beach? A: Sandy.” And we thought they were funny as hell.↩

Neoantigen vaccines use the DNA from a cancer patient’s own tumor to, hopefully, eradicate the cancer.

For some 50 years, cancer biologists have tried to incite the immune system to attack cancer by targeting molecules that commonly stud the surfaces of malignant cells. These “antigens” act as homing beacons that immune cells find and lock onto (much as antigens on viruses attract the immune system, the basis for preventive vaccines such as that for measles).

Trouble is, normal cells sometimes sport the same antigens as tumors, and the immune system is programmed not to attack antigens found on healthy cells. As a result, revving up the immune system to target common tumor antigens hasn’t worked, leading to a number of failed experimental cancer vaccines.

That led biologists to a different approach: siccing the immune system on antigens found only on cancer cells — and only on the cancer cells of a single patient. “It’s highly unlikely that any two patients have the same neoantigens,” said Dr. Catherine Wu of Boston’s Dana-Farber Cancer Institute. “That’s why we have an opportunity to make cancer vaccines truly personalized, loaded with patient-specific neoantigens.”

From the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, an animated map of the yearly migratory patterns of 118 bird species in the Western Hemisphere.

La Sorte says a key finding of the study is that bird species that head out over the Atlantic Ocean during fall migration to spend winter in the Caribbean and South America follow a clockwise loop and take a path farther inland on their return journey in the spring. Species that follow this broad pattern include Bobolinks, Yellow and Black-billed cuckoos, Connecticut and Cape May warblers, Bicknell’s Thrush, and shorebirds, such as the American Golden Plover.

“These looped pathways help the birds take advantage of conditions in the atmosphere,” explains La Sorte. “Weaker headwinds and a push from the northeast trade winds as they move farther south make the fall journey a bit easier. The birds take this shorter, more direct route despite the dangers of flying over open-ocean.”

The map was created with data from eBird, a database of crowdsourced bird sightings. They also created a follow-up map which labels each of the species. Look at how far Baird’s Sandpiper (#5) flies…all the way from central Argentina to Northern Canada and back. (thx, kevin)

The London Underground recently conducted an experiment on one of the escalators leading out of the busy Holborn station. Instead of letting people walk up the left side of the escalator, they asked them to stand on both sides.

The theory, if counterintuitive, is also pretty compelling. Think about it. It’s all very well keeping one side of the escalator clear for people in a rush, but in stations with long, steep walkways, only a small proportion are likely to be willing to climb. In lots of places, with short escalators or minimal congestion, this doesn’t much matter. But a 2002 study of escalator capacity on the Underground found that on machines such as those at Holborn, with a vertical height of 24 metres, only 40% would even contemplate it. By encouraging their preference, TfL effectively halves the capacity of the escalator in question, and creates significantly more crowding below, slowing everyone down. When you allow for the typical demands for a halo of personal space that persist in even the most disinhibited of commuters — a phenomenon described by crowd control guru Dr John J Fruin as “the human ellipse”, which means that they are largely unwilling to stand with someone directly adjacent to them or on the first step in front or behind — the theoretical capacity of the escalator halves again. Surely it was worth trying to haul back a bit of that wasted space.

Leaving aside “the human ellipse” for now,1 how did the theory work in the real life trial? The stand-only escalator moved more than 25% more people than usual:

But the preliminary evidence is clear: however much some people were annoyed, Lau’s hunch was right. It worked. Through their own observations and the data they gathered, Harrison and her team found strong evidence to back their case. An escalator that carried 12,745 customers between 8.30 and 9.30am in a normal week, for example, carried 16,220 when it was designated standing only. That didn’t match Stoneman’s theoretical numbers: it exceeded them.

But not everyone liked being asked to stand for the common good:

“This is a charter for the lame and lazy!” said one. “I know how to use a bloody escalator!” said another. The pilot was “terrible”, “loopy,” “crap”, “ridiculous”, and a “very bad idea”; in a one-hour session, 18 people called it “stupid”. A customer who was asked to stand still replied by giving the member of staff in question the finger. One man, determined to stride to the top come what may, pushed a child to one side. “Can’t you let us walk if we want to?” asked another. “This isn’t Russia!”

There’s a lesson in income inequality here somewhere…2

Update: The NY Times wades into the not walking on escalators debate: Why You Shouldn’t Walk on Escalators. Standing on the escalator, meet American self-interest.

It would be hard to persuade people that “everybody wins” if they all merely stood on the escalator, Curtis W. Reisinger, a psychologist at Zucker Hillside Hospital in Glen Oaks, N.Y., said.

“Overall I am not too optimistic that people’s sense of altruism can override their sense of urgency and immediacy in a major metro area where the demands for speed and expediency are high,” he wrote in an email.

Sam Schwartz, New York City’s former traffic commissioner and a fellow in transportation at Hunter College, said people’s competitive nature tends to trump logic and science.

“In the U.S., self-interest dominates our behavior on the road, on escalators and anywhere there is a capacity problem,” he wrote in an email. “I don’t believe Americans, any longer (if they ever did), have a rational button.”

There’s nothing more American than a few people gaining a few extra seconds at the expense of many having to wait a lot longer. See also Tom Junod’s piece from Esquire, The Water-Park Scandal and Two Americas in the Raw: Are We a Nation of Line-Cutters, or Are We the Line?

Update: Cheddar did a short video on standing vs walking on escalators:

What a phrase! Check out Fruin’s chapter on Designing for Pedestrians for more.↩

Ok, explicitly: the people standing are poor, the people walking are rich, and speed is income. When the walkers redistribute some of their speed to the whole group, on average everyone gets to where they’re going faster. But the walkers are unwilling to give up walking because they believe their own individual speed will prevail. “This isn’t Russia!” indeed.↩

This is America in a nutshell. Instead of banning kids from playing football, as the world’s leading expert on the football-related head injuries urges, a school district is having their football players drink a brand of chocolate milk that has been shown in a preliminary study to “improve their cognitive and motor function over the course of a season, even after experiencing concussions”.

Experimental groups drank Fifth Quarter Fresh after each practice and game, sometimes six days a week, while control groups did not consume the chocolate milk. Analysis was performed on two separate groups: athletes who experienced concussions during the season and those who did not. Both non-concussed and concussed groups showed positive effects from the chocolate milk.

Non-concussed athletes who drank Maryland-produced Fifth Quarter Fresh showed better cognitive and motor scores over nine test measures after the season as compared to the control group.

Concussed athletes drinking the milk improved cognitive and motor scores in four measures after the season as compared to those who did not.

Vice Sports has a quick look at what’s wrong with this study.

See also these new helmets designed to “prevent” concussions. The problem is not poorly designed helmets or lack of magic chocolate milk. Those things only make matters worse by implicitly condoning poor behavior, e.g. if helmets prevent concussions, it’ll gradually result in harder hitting, which will result in more injuries.

With hindsight, it seems bloody obvious the Sun and not the Earth is the center of the solar system. Occam’s razor and all that. (via @somniumprojec)

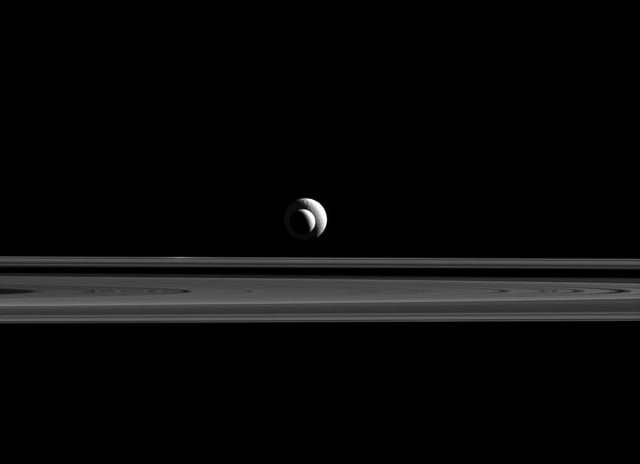

The Cassini spacecraft took a photo of two moons of Saturn, Tethys and Enceladus, beautifully aligned with each other. The cosmic ballet goes on. (via slate)

You know the vodka that comes in the Crystal Skull head?1 A forensic scientist used facial reconstruction techniques to give the skull a face.

Fun fact: immediately before I went onstage at Webstock, I drank at shot of Crystal Skull vodka. Funner fact: I also took some Vicodin (left over from a dental procedure), which typically mellows me out. Neither did a damn thing to calm my nerves. ¯\_(ツ)_/¯ ↩

IUPAC, the governing body for the official periodic table of elements, has announced the addition of four new elements to the table: ununtrium, ununpentium, ununseptium, and ununoctium. Those are working names…the teams that discovered each element has been invited to name them.

The proposed names and symbols will be checked by the Inorganic Chemistry Division of IUPAC for consistency, translatability into other languages, possible prior historic use for other cases, etc. New elements can be named after a mythological concept, a mineral, a place or country, a property or a scientist.

Ununoctium is so unstable that its half-life is 0.89 milliseconds and only three or four atoms of the substance have been produced in the past 10 years.

If you’re interested in strange stories involving brain tumors, fecal bacterium, and Institutional Review Boards, Emily Eakin’s “Bacteria on the Brain” for the New Yorker should be right up your alley.

Dr. Paul Muizelaar, then chair of the neurosurgery department at U.C. Davis, undertook a daring approach to treating brain tumors. It might work, but would it help?

The previous month, he had operated on Patrick Egan, a fifty-six-year-old real-estate broker, who also suffered from glioblastoma. Egan was a friend of Muizelaar’s, and, like Terri Bradley, he had exhausted the standard therapies for the disease. The tumor had spread to his brain stem and was shortly expected to kill him. Muizelaar cut out as much of the tumor as possible. But before he replaced the “bone flap” — the section of skull that is removed to allow access to the brain — he soaked it for an hour in a solution teeming with Enterobacter aerogenes, a common fecal bacterium. Then he reattached it to Egan’s skull, using tiny metal plates and screws. Muizelaar hoped that inside Egan’s brain an infection was brewing.

Kurzgesagt makes some of the most entertaining science explainers around. Check out their most recent video on black holes.

The winner of the 2015 Small World in Motion competition is Wim van Egmond’s video of a single-celled organism consuming a smaller single-celled organism. The winners of the photomicrography contest are worth a look as well.

Over the years, there’s been a growing consensus that suggests being happy is correlated with living a long life. Well, you can wipe that smile off your face because a massive study published in The Lancent makes it clear that no such correlation exists. So what about all those studies suggesting that stress and joylessness hastened death’s arrival? According the new study’s co-author:

In our view, the previous studies haven’t been well done. All that’s going on is ill health actually was causing unhappiness and stress.

In other words, your unhappiness is going to last longer than you thought.

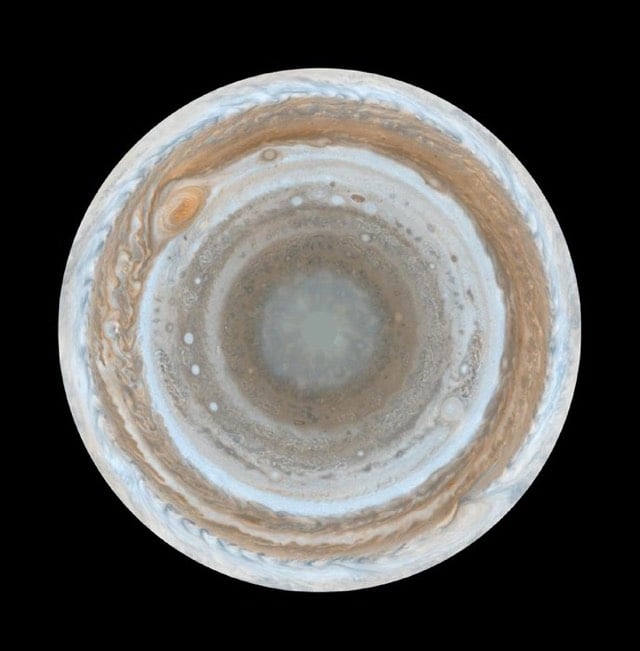

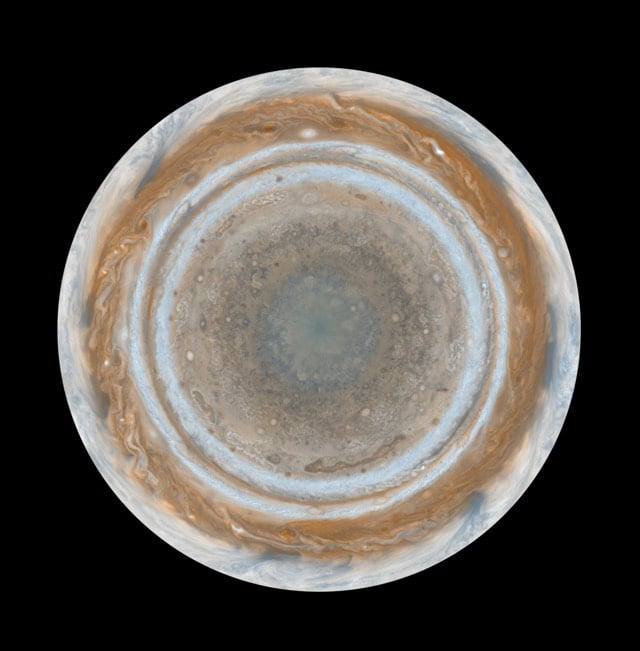

When you see photos of Jupiter, they’re almost always the of same view: the north pole at the top, the gaseous bands perfectly horizontal, and the Red Spot somewhere in the mix. But @robdubbin reminds us that there are other ways of looking at Jupiter. Here’s a view of the planet’s southern hemisphere:

And the northern hemisphere:

If you take photos of the whole of Jupiter’s surface and stretch it out flat, you get something like this:

That last one in particular is worth checking out at full resolution. (via @tcarmody)

If you take two circular magnets and slap them on the ends of a AA battery, the resulting axel will drive on a road of aluminum foil. This is called a homopolar motor and it’s one of the simplest machines you can build. How does it work? Well, it’s been awhile since my last electromagnetism class, but the homopolar motor works because the combination of the flow of the electric current (from the battery) and the flow of the magnetic current produces a torque via the Lorenz force. This short video explanation should give you a good idea of the principles involved. (via digg)

A European Space Agency probe will be launched into space early next month to help test the last major prediction of Einstein’s theory of general relativity: the existence of gravitational waves.

Gravitational waves are thought to be hurled across space when stars start throwing their weight around, for example, when they collapse into black holes or when pairs of super-dense neutron stars start to spin closer and closer to each other. These processes put massive strains on the fabric of space-time, pushing and stretching it so that ripples of gravitational energy radiate across the universe. These are gravitational waves.

The Lisa Pathfinder probe won’t measure gravitational waves directly, but will test equipment that will be used for the final detector.

LISA Pathfinder will pave the way for future missions by testing in flight the very concept of gravitational wave detection: it will put two test masses in a near-perfect gravitational free-fall and control and measure their motion with unprecedented accuracy. LISA Pathfinder will use the latest technology to minimise the extra forces on the test masses, and to take measurements. The inertial sensors, the laser metrology system, the drag-free control system and an ultra-precise micro-propulsion system make this a highly unusual mission.

(via @daveg)

Why isn’t it super-fast to fly west in an airplane, given that the Earth is spinning at 700-1000 miles per hour relative to its center? This seems like a sorta-variation on the old airplane on a treadmill question, doesn’t it?

The Cassini probe, launched from Earth in 1997 (six months before I started publishing kottke.org), has been taking photos of Saturn and its moons for 11 years now. The Wall Street Journal has a great feature that shows exactly what the probe has been looking at all that time. (Note: the video above features flashing images, so beware if that sort of thing is harmful to you.)

Stay Connected