kottke.org posts about lists

Jordan Hoffman is a huge huge huge Star Trek fan. So great is his fandom that he is able to rank every single episode from every single Star Trek series from #695 to #1. Several TNG episodes make it into the top 10, including Yesterday’s Enterprise, Darmok, and The Best of Both Worlds.

Physics World, the magazine of the Institute of Physics, has named their 2014 Breakthrough of the Year and nine runners-up. The top spot goes to the ESA’s Rosetta mission for landing on a comet.

By landing the Philae probe on a distant comet, the Rosetta team has begun a new chapter in our understanding of how the solar system formed and evolved — and ultimately how life was able to emerge on Earth. As well as looking forward to the fascinating science that will be forthcoming from Rosetta scientists, we also acknowledge the technological tour de force of chasing a comet for 10 years and then placing an advanced laboratory on its surface.

The other nine achievements, which you can click through to read about, are:

Quasar shines a bright light on cosmic web

Neutrinos spotted from Sun’s main nuclear reaction

Laser fusion passes milestone

Electrons’ magnetic interactions isolated at long last

Disorder sharpens optical-fibre images

Data stored in magnetic holograms

Lasers ignite ‘supernovae’ in the lab

Quantum data are compressed for the first time

Physicists sound-out acoustic tractor beam

Rolling Stone lists the 40 most groundbreaking music albums in history. Kanye West makes the list with 808s and Heartbreaks, Dr. Dre with The Chronic, Nirvana with Nevermind, and the Beatles with Rubber Soul and Sgt. Pepper’s. About The Chronic:

The album sold a world to white America that it had never really seen before, and packaged it with a soundtrack so funky there was no avoiding it. It was both raw, uncut underground and carefully composed pop. If Public Enemy confronted white America, The Chronic seduced it. For the first time ever, hip-hop’s mainstream and America’s were one.

I counted only four women artists though: Mary J. Blige, Loretta Lynn, Nico, and Carole King.

kottke.org favorite Matt Zoller Seitz weighs in on his top 10 best TV shows for 2014. For someone who doesn’t watch a ton of TV, I have seen a surprising number of these.

My friend David has been trying to tell me about Hannibal, but I haven’t been listening. Maybe I should start? Olive Kitteridge was great; Frances McDormand was incredible. True Detective was pretty good and I was lukewarm on Cosmos (I have NDT issues). Mad Men continues to be great…I keep waiting for it to fall off in quality, but it hasn’t happened. The Roosevelts was really interesting and like Seitz, I find myself thinking about it often. I’ve seen bits and pieces of John Oliver but I get enough of the “humans are awful ha ha” news on Twitter to become a regular viewer.

Other shows I’ve watched that aren’t on the list: Downton Abbey (my favorite soap), Game of Thrones (tied w/ Mad Men for my fave current show, although MM is better), Boardwalk Empire (strong finish), Sherlock (still fun, tho got a bit too self referential there), and Girls (gave up after s03e04 when it was airing but recently powered through rest of the 3rd season and is back in my good graces).

Businessweek is 85 years old and to celebrate, they’ve listed the 85 most disruptive ideas created during that time. They include kitty litter, Air Jordans, information theory, refrigeration, the jet engine, and the Polaroid camera.

Polaroids were the first social network. You’d take a picture, and someone would say, “I want one, too,” so you’d give it away and take another. People shared Polaroids the way they now share information on social media. Of course, it was more personal, because you were sharing with just one person, not the entire world.

I met Andy Warhol in the ’70s at the Whitney Museum and started doing projects with him because he loved my photographs. He’d never had a pal who was a photographer, so I was his guru, showing him what cameras to buy, what pictures to take. When Polaroid came out with its SX-70 model, the company sent big boxes of film and cameras to the Factory, which was at 860 Broadway (it’s now a Petco). Andy loved Polaroid. Everything was “gee whiz”; it was brand-new. So immediate. I took photos of him with his new toy.

From the emergence of markets in the 13th century to the scientific revolution of the 17th century to castles in the 11th century, this is a list of historian Ian Mortimer’s 10 biggest changes of the past 1000 years.

Most people think of castles as representative of conflict. However, they should be seen as bastions of peace as much as war. In 1000 there were very few castles in Europe — and none in England. This absence of local defences meant that lands were relatively easy to conquer — William the Conqueror’s invasion of England was greatly assisted by the lack of castles here. Over the 11th century, all across Europe, lords built defensive structures to defend them and their land. It thus became much harder for kings to simply conquer their neighbours. In this way, lords tightened their grip on their estates, and their masters started to think of themselves as kings of territories, not of tribes. Political leaders were thus bound to defend their borders — and govern everyone within those borders, not just their own people. That’s a pretty enormous change by anyone’s standards.

The list is adapted from Mortimer’s recent book, Centuries of Change.

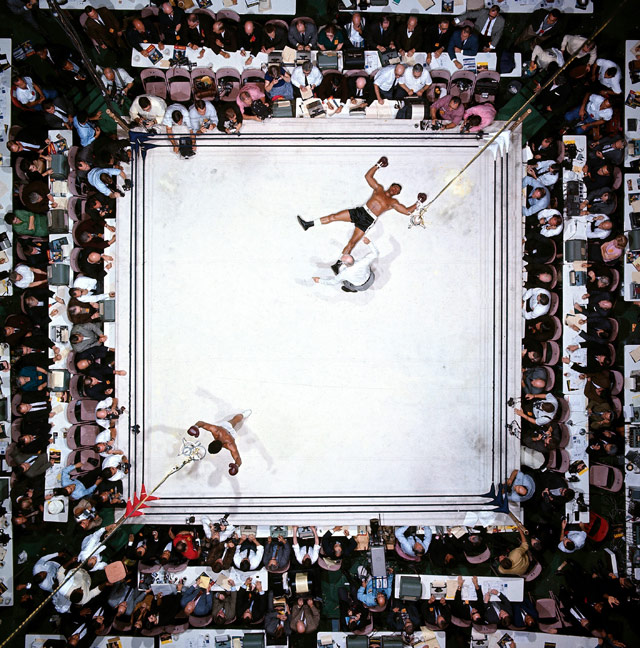

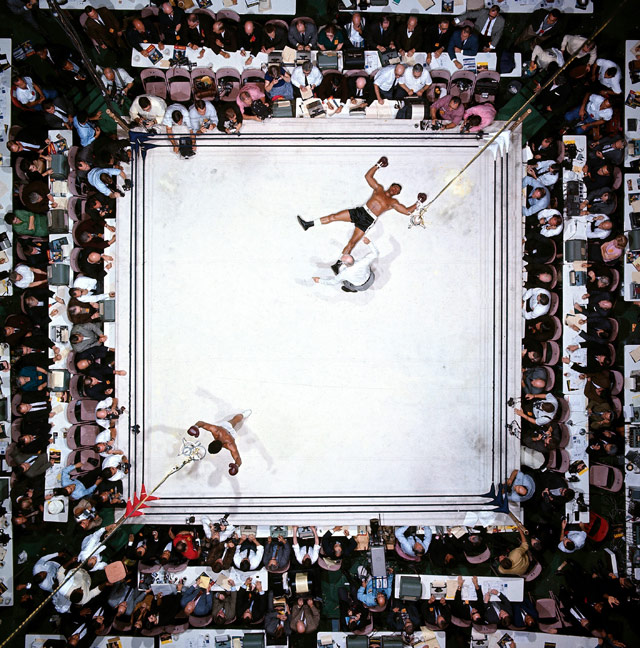

From the Guardian’s photo editor, an annotated list of the 25 best photographs of Muhammad Ali. My favorite is by Neil Leifer:

(via @DavidGrann)

From Silence of the Lambs (#1) to To Kill A Mocking Bird (#9) to Blade Runner (#28), these are the 50 best book-to-movie adaptations ever, compiled by Total Film.

Somehow absent is Spike Jonze’s Adaptation and I guess 2001 was not technically based on a book, but whatevs. The commenters additionally lament the lack of Requiem for a Dream, Gone with the Wind, The French Connection, Rosemary’s Baby, Last of the Mohicans, and The Wizard of Oz.

From CineFix, their top ten slow motion sequences of all time.

Includes scenes from The Matrix, Hard Boiled, Reservoir Dogs, and The Shining. But no Wes Anderson!?! *burns down internet* (via @DavidGrann)

Flavorwire collected a list of the favorite books of 50 well-known people, including Bill Murray, Amy Poehler, Ayn Rand, and Caroline Kennedy. Here are some of the picks:

Bill Murray: The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn by Mark Twain.

Dolly Parton: The Little Engine That Could by Watty Piper.

Joan Didion: Victory by Joseph Conrad.

Robin Williams: The Foundation Trilogy by Isaac Asimov.

Michelle Obama: Song of Solomon by Toni Morrison.

Nikola Tesla: Faust by Johann Wolfgang Von Goethe.

(via @davidgrann)

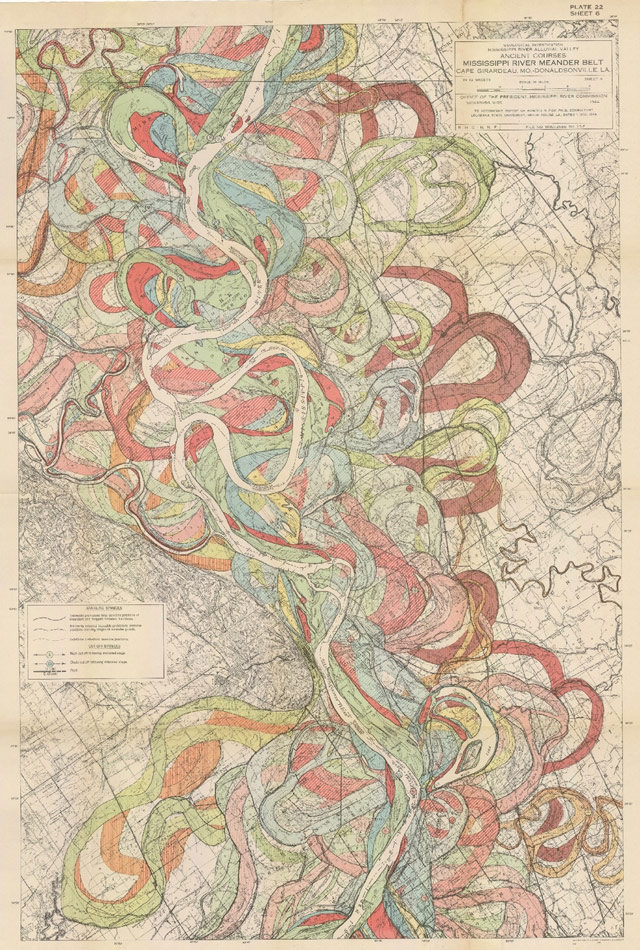

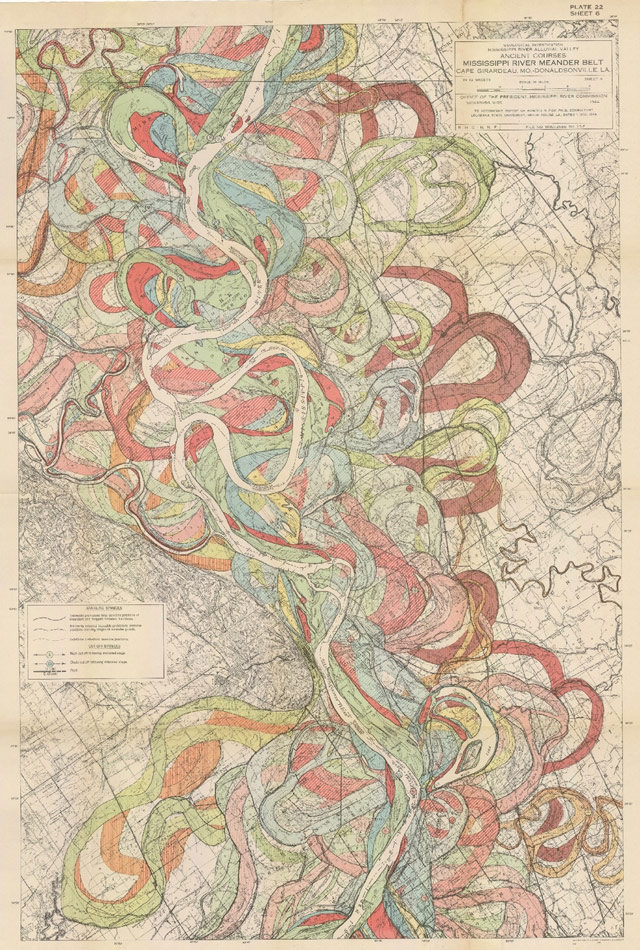

Bill Rankin of radicalcartography picks his five favorite maps. The historical meanderings of the Mississippi River map from an Army Corps of Engineers report is a favorite of mine too:

How do you pick just 10 essays for a list of the best essays since 1950? You exclude any New Journalism, non-American writers, and even so, it must have been difficult. Here’s Robert Atwan’s full list and a few of his choices:

Susan Sontag, “Notes on ‘Camp’”

David Foster Wallace, “Consider the Lobster”

Annie Dillard, “Total Eclipse”

John McPhee, “The Search for Marvin Gardens”

Many of the essays are available online…ladies and gentlemen, start your Instapapers.

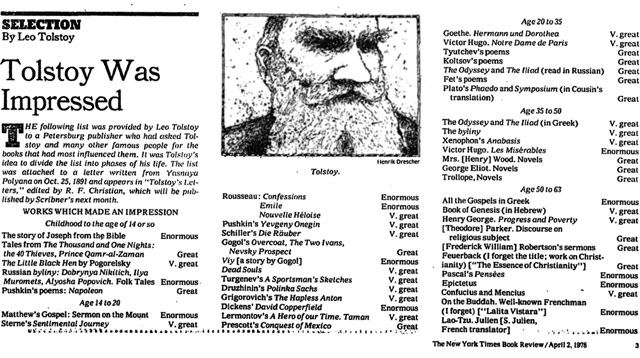

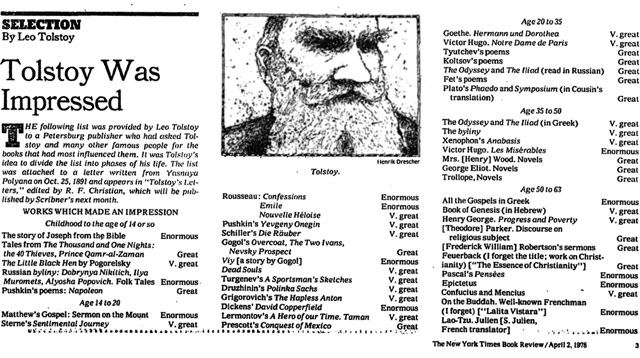

When Russian author Leo Tolstoy was in his 60s, he was asked to list the books which influenced him the most in his career. He responded by grouping the books into three main categories by level of impact: great, v. great, and enormous. Some of his picks:

Matthew’s Gospel: Sermon on the Mount - Enormous

Dickens’ David Copperfield - Enormous

Victor Hugo. Les Misérables - Enormous

Pushkin’s Yevgeny Onegin - V. great

George Eliot. Novels - Great

The NY Times reprinted the list in 1978; here’s the original listing.

According to Rolling Stone, 1984 was the greatest year in pop music history. And they made a list of the top 100 singles from that year; here’s the top 5:

5. Thriller, Michael Jackson

4. Let’s Go Crazy, Prince

3. I Feel for You, Chaka Khan

2. Borderline, Madonna

1. When Doves Cry, Prince

1984 was also a fine year for movies and the most 1980s year of the 1980s. Both Bill Simmons and Aaron Cohen agree, 1984 was the best year.

From Wikipedia, a list of common misconceptions, including a recent favorite about life expectancy in the Middle Ages:

It is true that life expectancy in the Middle Ages and earlier was low; however, one should not infer that people usually died around the age of 30. In fact, the low life expectancy is an average very strongly influenced by high infant mortality, and the life expectancy of people who lived to adulthood was much higher. A 21-year-old man in medieval England, for example, could by one estimate expect to live to the age of 64.

Also, Vikings didn’t wear horned helmets, Romans didn’t puke in vomitoriums after rich meals, the average housefly lives for 20 to 30 days, medieval Europeans didn’t believe the Earth was flat, Napoleon was taller than average, the Bible’s forbidden fruit was not explicitly an apple, and humans have more than 20 senses. (via @linuz90)

New Yorker music critic Sasha Frere-Jones recently compiled a series of five playlists on Spotify of “perfect” songs: vol 1, vol 2, vol 3, vol 4, vol 5. Among the songs found on the playlists are Maps by Yeah Yeah Yeahs, Blue Moon by Elvis, Pony by Ginuwine, Transmission by Joy Division, Tennis Court by Lorde, No Scrubs by TLC, and Rock Steady by Aretha Franklin. The playlists are also available on Rdio, courtesy of my friend Matt: vol 1, vol 2, vol 3, vol 4, and vol 5.

Update: And here’s an Rdio playlist with all five volumes of Perfect Recordings. This will be on shuffle at my place for months to come.

From Matter, a list of things to enjoy now before climate change takes them away or makes them more difficult to procure. Like Joshua trees:

The Joshua trees of Joshua Tree National Park need periods of cold temperatures before they can flower. Young trees are now rare in the park.

And chocolate:

Steep projected declines in yields of maize, sorghum, and other staples portend a coming food crisis for parts of sub-Saharan Africa. But here’s what will probably get everyone’s attention in the developed world: Studies suggest cacao production will begin to decline in Ghana and the Ivory Coast, the source of half of the world’s chocolate, by 2030.

And cherries:

Eighty percent of tart cherries come from a single five-county area in Michigan, all of which is threatened.

But as noted previously, we’ve got plenty of time to enjoy jellyfish:

Important cold-water fish species, including cod, pollock, and Atlantic Salmon, face a growing threat of population collapse as the oceans heat up. Studies suggest a radical fix: Eat lots of jellyfish, which will thrive in our new climate.

Also, The Kennedy Space Center, Havana, Coney Island, the Easter Island statues, and The Leaning Tower of Pisa will all be underwater sooner than you think.

Holy informational rabbit hole, Batman! Wikipedia has a page that is a List of lists of lists.

This article is a list of articles comprising a list of things that are themselves lists of things, such as the lists of lists listed below.

Inception horn! Includes such lists of lists as Lists of fictional Presidents of the United States, Ranked lists of Chilean regions, Lists of black people, and Lists of nuclear disasters and radioactive incidents. (via @sampotts)

Today’s brain-melter: Every Insanely Mystifying Paradox in Physics. It’s all there, from the Greisen-Zatsepin-Kuzmin limit to quantum immortality to, of course, the tachyonic antitelephone.

A tachyonic antitelephone is a hypothetical device in theoretical physics that could be used to send signals into one’s own past. Albert Einstein in 1907 presented a thought experiment of how faster-than-light signals can lead to a paradox of causality, which was described by Einstein and Arnold Sommerfeld in 1910 as a means “to telegraph into the past”.

If you emerge with your brain intact, at the very least, you’ll have lost a couple of hours to the list.

In light of the ongoing policing situation in Ferguson, Missouri in the wake of the shooting of an unarmed man by a police officer and how the response to the community protests is highlighting the militarization of US police departments since 9/11, it’s instructive to look at one of the first and most successful attempts at the formation of a professional police force.

The UK Parliament passed the first Metropolitan Police Act in 1829. The act was introduced by Home Secretary Sir Robert Peel, who undertook a study of crime and policing, which resulted in his belief that the keys to building an effective police force were to 1) make it professional (most prior policing had been volunteer in nature); 2) organize as a civilian force, not as a paramilitary force; and 3) make the police accountable to the public. The Metropolitan Police, whose officers were referred to as “bobbies” after Peel, was extremely successful and became the model for the modern urban police force, both in the UK and around the world, including in the United States.

At the heart of the Metropolitan Police’s charter were a set of rules either written by Peel or drawn up at some later date by the two founding Commissioners: The Nine Principles of Policing. They are as follows:

1. To prevent crime and disorder, as an alternative to their repression by military force and severity of legal punishment.

2. To recognise always that the power of the police to fulfil their functions and duties is dependent on public approval of their existence, actions and behaviour, and on their ability to secure and maintain public respect.

3. To recognise always that to secure and maintain the respect and approval of the public means also the securing of the willing co-operation of the public in the task of securing observance of laws.

4. To recognise always that the extent to which the co-operation of the public can be secured diminishes proportionately the necessity of the use of physical force and compulsion for achieving police objectives.

5. To seek and preserve public favour, not by pandering to public opinion, but by constantly demonstrating absolutely impartial service to law, in complete independence of policy, and without regard to the justice or injustice of the substance of individual laws, by ready offering of individual service and friendship to all members of the public without regard to their wealth or social standing, by ready exercise of courtesy and friendly good humour, and by ready offering of individual sacrifice in protecting and preserving life.

6. To use physical force only when the exercise of persuasion, advice and warning is found to be insufficient to obtain public co-operation to an extent necessary to secure observance of law or to restore order, and to use only the minimum degree of physical force which is necessary on any particular occasion for achieving a police objective.

7. To maintain at all times a relationship with the public that gives reality to the historic tradition that the police are the public and that the public are the police, the police being only members of the public who are paid to give full-time attention to duties which are incumbent on every citizen in the interests of community welfare and existence.

8. To recognise always the need for strict adherence to police-executive functions, and to refrain from even seeming to usurp the powers of the judiciary of avenging individuals or the State, and of authoritatively judging guilt and punishing the guilty.

9. To recognise always that the test of police efficiency is the absence of crime and disorder, and not the visible evidence of police action in dealing with them.

As police historian Charles Reith noted in 1956, this philosophy was radical when implemented in London in the 1830s and “unique in history and throughout the world because it derived not from fear but almost exclusively from public co-operation with the police, induced by them designedly by behaviour which secures and maintains for them the approval, respect and affection of the public”. Apparently, it remains radical in the United States in 2014. (thx, peter)

Sight and Sound polled 340 critics and filmmakers in search of the world’s best documentary films. Here are their top 50. From the list, the top five:

A Man with a Movie Camera

Shoah

Sans soleil

Night and Fog

The Thin Blue Line

Unless you went to film school or are a big film nerd, you probably haven’t seen (or even heard of) the top choice, A Man with a Movie Camera. Roger Ebert reviewed the film several years ago as part of his Great Movies Collection.

Born in 1896 and coming of age during the Russian Revolution, Vertov considered himself a radical artist in a decade where modernism and surrealism were gaining stature in all the arts. He began by editing official newsreels, which he assembled into montages that must have appeared rather surprising to some audiences, and then started making his own films. He would invent an entirely new style. Perhaps he did. “It stands as a stinging indictment of almost every film made between its release in 1929 and the appearance of Godard’s ‘Breathless’ 30 years later,” the critic Neil Young wrote, “and Vertov’s dazzling picture seems, today, arguably the fresher of the two.” Godard is said to have introduced the “jump cut,” but Vertov’s film is entirely jump cuts.

If you’re curious, the film is available on YouTube in its entirety:

(via open culture)

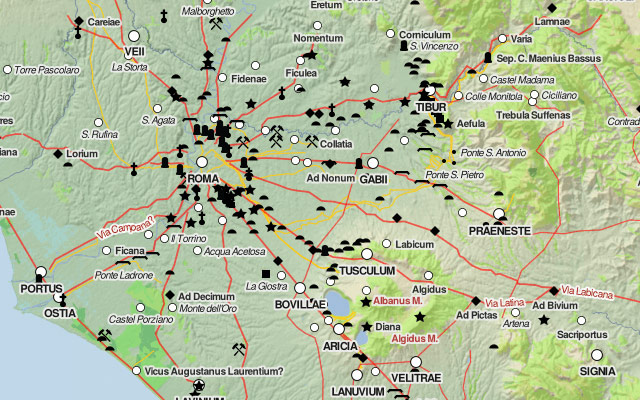

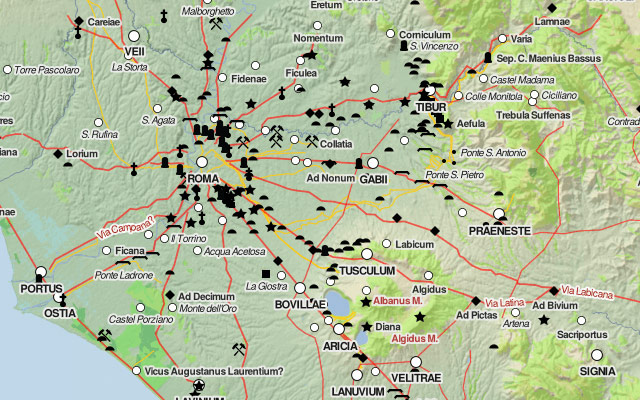

The Digital Atlas of the Roman Empire lets you explore ancient Rome in a Google Maps interface. (via @pbump)

Update: From Vox, 40 Maps That Explain the Roman Empire.

Two thousand years ago, on August 19, 14 AD, Caesar Augustus died. He was Rome’s first emperor, having won a civil war more than 40 years earlier that transformed the dysfunctional Roman Republic into an empire. Under Augustus and his successors, the empire experienced 200 years of relative peace and prosperity. Here are 40 maps that explain the Roman Empire — its rise and fall, its culture and economy, and how it laid the foundations of the modern world.

Over at McSweeney’s, David Tate imagines more engaging copy for the Ten Commandments, aka you won’t believe what God said to this man…

At the Beginning He Had Me Confused, But by Minute Two I Knew That I Shouldn’t Have Other Gods.

37 Things in Your Bedroom That You Need to Get Rid of Right Now, Like Adulteresses.

From CineFix, a collection of ten of the most iconic and memorable editing moments in cinematic history.

(via @brillhart)

The staff and contributors of Dissolve recently listed the 50 greatest summer blockbusters ever. Here’s #50-31, #30-11, and the top 10.

Blockbusters have become such an integral part of the way we talk about films that it’s hard to believe they haven’t always been with us. But while there have always been big movies-lavish productions designed to draw crowds and command repeat business-the blockbuster as we know it has a definite start date: June 20, 1975. That’s when Jaws first hit screens in the middle of what was once, in the words of The Financial Times, a “low season” when the “only steady summer dollars came, in the U.S., from drive-in theaters.” It’s summer, after all; why go to the movies when you could be outside? Jaws changed that. Star Wars cemented that change. And now, the summer-movie season is dominated by the biggest films Hollywood has to offer.

Jaws is the no-surprise #1 but Who Framed Roger Rabbit at #8? Hmm, dunno about that. And leaving Star Wars just off the top 10 is a bold move. My personal top ten would also have included Ghostbusters — I remember vividly waiting in line in the sweltering heat outside the El Lago theater to see Ghostbusters and just being completely and utterly blown away by it — and Terminator 2. Oh and Batman. I think I saw that movie half-a-dozen times in the theater and it was just everywhere that summer…the logo, that song by Prince, everything. (via @khoi)

Earlier today I asked my Twitter followers for recommendations for “really good” biographies about scientists. I gave Genius (James Gleick’s bio of Richard Feynman) and Cleopatra, A Life (not about a scientist but was super interesting and well-written) as examples of what I was looking for. You can see the responses here and I’ve pulled out a few of the most interesting ones below:

- Isaac Newton by James Gleick. Gleick wrote the aforementioned Genius and Chaos, another favorite of mine. I tried to read The Information last year after many glowing recommendations from friends but couldn’t get into it. Someone suggested Never at Rest is a superior Newton bio.

- The Man Who Loved Only Numbers by Paul Hoffman. I’ve read this biography of mathematician Paul Erdos; highly recommended.

- Galileo’s Daughter by Dava Sobel. I’ve never read anything by Sobel; I’ll have to rectify that.

- Einstein: His Life and Universe by Walter Isaacson. I enjoyed his problematic Jobs biography and I notice that he’s written one on Ben Franklin as well.

- Alan Turing: The Enigma by Andrew Hodges.

- American Prometheus by Kai Bird and Martin Sherwin. Bio of J. Robert Oppenheimer, leader of the Manhattan Project. See also: The Making of the Atomic Bomb, one of my favorite books ever.

- Everything and More by David Foster Wallace. I’ve heard Wallace was bit handwavy with the math in this one, but I still enjoyed it.

- Newton and the Counterfeiter by Thomas Levenson. Newton was a detective?

- The Philosophical Breakfast Club by Laura Snyder. Four-way bio of a group of school friends (Charles Babbage, John Herschel, William Whewell, and Richard Jones) who changed the world.

- The Reluctant Mr. Darwin by David Quammen. How Charles Darwin devised his theory of evolution and then sat on it for years is one of science’s most fascinating stories.

- T. rex and the Crater of Doom by Walter Alvarez. Not a biography of a person but of a theory: that a meteor impact 65 million years ago caused the extinction of the dinosaurs.

- Walt Disney by Neal Gabler. Disney isn’t a scientist, but when you ask for book recommendations and Steven Johnson tells you to read something, it goes on the list.

- The Man Who Knew Infinity by Robert Kanigel. Bio of brilliant Indian mathematician Srinivasa Ramanujan.

- Edge of Objectivity by Charles Gillispie. A biography of modern science published in 1966, all but out of print at this point unfortunately.

- Galileo at Work by Stillman Drake.

- The Age of Wonder by Richard Holmes.

And many more here. Thanks to everyone who suggested books.

Update: Because this came up on Twitter, some biographies specifically about women in science: The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, Hedy’s Folly, On a Farther Shore, Marie Curie: A Life, A Feeling for the Organism, Rosalind Franklin: The Dark Lady of DNA, Jane Goodall: The Woman Who Redefined Man, and Radioactive.

There haven’t been many good books written about soccer, but here are eleven of them worth your time. Franklin Foer’s How Soccer Explains the World: An Unlikely Theory of Globalization looks especially interesting.

A groundbreaking work — named one of the five most influential sports books of the decade by Sports Illustrated — How Soccer Explains the World is a unique and brilliantly illuminating look at soccer, the world’s most popular sport, as a lens through which to view the pressing issues of our age, from the clash of civilizations to the global economy.

Foer is one of the contributors, alongside authors Aleksandar Hemon and Karl Ove Knausgaard, to the New Republic’s excellent World Cup coverage.

Over the course of his 3000 columns at The Motley Fool, Morgan Housel has learned a few things:

I’ve learned that short-term thinking is at the root of most of our problems, whether it’s in business, politics, investing, or work.

I’ve learned that debt can cause more social problems than some drugs, yet drugs are illegal and debt is tax deductible.

I’ve learned that finance is actually very simple, but it’s made to look complicated to justify fees.

Unfortunately, the list is undermined almost completely by the get-rich-quick advertising on the site, including this bit at the end of the article, which I can’t even tell is an ad or just a promotion:

Opportunities to get wealthy from a single investment don’t come around often, but they do exist, and our chief technology officer believes he’s found one. In this free report, Jeremy Phillips shares the single company that he believes could transform not only your portfolio, but your entire life. To learn the identity of this stock for free and see why Jeremy is putting more than $100,000 of his own money into it, all you have to do is click here now.

Short-term thinking is at the root of most of our problems, click here now. Now!

Newer posts

Older posts

Stay Connected