kottke.org posts about film school

If you’ve seen a superhero film in the past 10-15 years, chances are that when you see a character wearing a suit, what you’re seeing is almost 100% computer generated. Sometimes the character on the screen is motion-captured but sometimes it’s completely animated. It’s amazing how much these movies are made like animated movies — they can make so many different kinds of changes (clothes, movements, body positioning) way after filming is completed. (via @tvaziri)

Francis Ford Coppola, a legendary filmmaker no matter how you slice it, sat down recently to talk through his most notable films: The Godfather films, The Conversation, Apocalypse Now, and a new movie he’s working on called Megalopolis. I really enjoyed this. Some tidbits:

- Coppola didn’t know anything about the Mafia before making The Godfather.

- The studio did not want to call it Godfather Part II. And now explicit sequels like that are ubiquitous.

- He praised the way Marlon Brando thought about ants and termites?!

- I’d missed that Godfather Part III had been recently recut and rechristened “Mario Puzo’s The Godfather, Coda: The Death of Michael Corleone”, which is what Coppola wanted to call it all along.

And this is a great way to think about creative projects:

Learning from the great Elia Kazan, I always try to have a word that is the core of what the movie is really about — in one word. For “Godfather,” the key word is succession. That’s what the movie is about. Apocalypse Now,” morality. “The Conversation,” privacy.

(via open culture)

In a series of video meditations on what he calls “Practices of Viewing”, Johannes Binotto explores techniques that filmmakers have used since the invention of film but are now within the control of home viewers: fast forward, mute, pause, screenshotting, and masking. Great stuff; this series was the most-mentioned in the recent Sight & Sound poll of the best video essays of 2021. Communications professor Katie Bird wrote of Practices of Viewing:

Beyond inspirational, and field changing, nothing made me want to throw in the towel on making more than seeing Binotto’s playful, critical, and incisive video series Practices of Viewing. Each one challenged our ways of ‘seeing’ and making, each one carefully bringing in new techniques to test the boundaries and possibilities of videographic form. But whatever trepidation I felt, was always overshadowed by the openness and curiosity that grounded each of Binotto’s experiments and his welcomeness as a videographic maker joyfully throwing out these gambits for the rest of us to up our games.

They’re so good and succinct, but somehow only one of them has over 500 views (and even that one hasn’t broken 1000 views). If you’re even a casual student or fan of film, take a few minutes to watch the first one and you’ll get sucked into the rest.

Typically, we think of music in movies in terms of what the music adds to the visuals. Music often tells us how to feel about what we’re seeing — it sets the mood and provides an emotional context. But, as Evan Puschak details in this video, you can also learn something about music (Mozart, in this case) from the way in which talented directors and music producers deploy it in movies, particularly when they use it unconventionally.

[These films and TV shows] teach us something about the Lacrimosa. They open up doors in the music that maybe even Mozart didn’t see. This is what’s so cool about movies — they bring art forms together and, in these collisions, it’s possible to see some really beautiful sparks.

These days, movies, TV shows, and even commercials all use something called the Dutch angle,1 a filmmaking technique where the camera is angled to produce a tilted scene, often to highlight that something is not quite right. The technique originated in Germany, inspired by Expressionist painters.

It was pioneered by German directors during World War I, when outside films were blocked from being shown in Germany. Unlike Hollywood, which was serving up largely glamorous, rollicking films, the German film industry took inspiration from the Expressionist movement in art and literature, which was focused on processing the insanity of world war. Its themes touched on betrayal, suicide, psychosis, and terror. And Expressionist films expressed that darkness not just through their plotlines, but their set designs, costumes… and unusual camera shots.

This got me thinking about my favorite shot from Black Panther, this camera roll in the scene where Killmonger takes the Wakandan throne:

It’s the Dutch angle but even more dynamic and it blew me away the first time I saw it. I poked around a little to see if this particular move had been done before (if director Ryan Coogler and cinematographer Rachel Morrison were referencing something specific) and I found Christopher Nolan (although I’d argue that he uses it in a slightly different way) and Stranger Things (in the scene starting at 1:33). Anywhere else?

From Patrick Willems, a history and celebration/defense of movie opening title sequences. They have fallen out of favor over the past decade or two, but Willems argues they serve a needed purpose. For instance, opening title sequences can set the tone or theme of the film before it even gets started — that’s what Saul Bass set out to do:

Bass called this “creating a climate for the story”. Here’s one of Willems’ favorite opening sequences by Bass, from 1966’s Grand Prix, which I’d somehow never seen before and is fantastic:

Me? I love opening title sequences. (Except when they are bad and too long.) But I also love when the movie starts right away. And when the movie starts right away and then you get a title card like 8 minutes into it. I’m a fan of anything when it’s done well. *shrugs*

P.S. You can check out hundreds of great examples of opening title sequences at Art of the Title.

I love Evan Puschak’s short analysis of a two-and-a-half minute scene from Sam Raimi’s 2004 film, Spider-Man 2. Raimi, a horror movie veteran, basically snuck a tight horror sequence into a PG-13 superhero movie — it’s a little cheesy, bloodless, and terrifying.

I don’t know if a 10-second sequence of a plane landing in one of Brian De Palma’s worst films properly qualifies as “The Most Difficult Shot in Movie History”, but the story behind it is genuinely interesting. The logistics of having only 30 seconds out of an entire year to get this exact shot of the setting sun and coordinating that with a landing supersonic jet at one of the world’s busiest airports are certainly daunting. As Patrick Willems notes in his commentary, this shot also signifies the end of an era in the film industry.

The Texas Switch is a filmmaking technique in which an actor and stunt person are switched seamlessly during a single shot — the actor steps out of the frame or behind a prop and the stunt person steps in (or vice versa). The lack of cutting keeps the narrative going and helps to obscure the switcheroo. The video above contains many great examples of the technique.

See also some Texas Switches from James Bond movies. (via storythings)

I keep tabs on a few trusted film school-ish YouTube channels and while I like when they cover films I’ve seen or those directed by my favorite directors, it’s more valuable when they introduce me to something new. Evan Puschak’s Nerdwriter is a particular favorite guiding light and in his latest video, he talks about Agnès Varda’s Cléo from 5 to 7, a film I now want to watch as soon as possible. A synopsis via Wikipedia:

Cléo from 5 to 7 follows a pop singer through two extraordinary hours in which she awaits the results of a recent biopsy. The film is superficially about a woman coming to terms with her mortality, which is a common auteurist trait for Varda. On a deeper level, Cléo from 5 to 7 confronts the traditionally objectified woman by giving Cléo her own vision. She cannot be constructed through the gaze of others, which is often represented through a motif of reflections and Cléo’s ability to strip her body of “to-be-looked-at-ness” attributes (such as clothing or wigs). Stylistically, Cléo from 5 to 7 mixes documentary and fiction, as had La Pointe Courte. The film represents diegetic action said to occur between 5 and 7 p.m., although its run-time is 89 minutes.

I’ve added Cléo from 5 to 7 to my HBO Max queue but you can also find it on Kanopy (accessible with a library card) and The Criterion Channel.

In this short video, YouTuber Paul E.T. shows how you can make a Netflix-style true crime documentary about anything. Even stolen toast. The equipment needs are pretty minimal - a good camera, a couple of lenses, some lighting, and a decent mic. The magic is in the editing. (via my son’s insistence that I click on this while browsing YouTube on the TV last night)

The YouTube channel In Depth Cine has been looking at how directors like Spike Lee, Alfonso Cuarón, Martin Scorsese, and Wes Anderson shoot films at three different budget levels, from the on-a-shoestring films early in their careers to later blockbusters, to see the similarities and differences in their approaches. For instance, Wes Anderson made Bottle Rocket for $5 million, Rushmore for $10 million, and Grand Budapest Hotel for $25 million:

Steven Spielberg shot Duel for $450,000, Raiders of the Lost Ark for $20 million, and Saving Private Ryan for $70 million:

Christopher Nolan did Following for $6,000, Memento for $9 million, and Inception for $160 million:

You can find the full playlist of 3 Budget Levels videos here. (This list really needs some female directors — Ava DuVernay, Sofia Coppola, and Kathryn Bigelow would be easy to do, for starters. And Chloé Zhao, after The Eternals gets released.)

As an unapologetic fan of James Cameron’s Titanic, I really enjoyed Evan Puschak’s video love letter to the film and the genre it embodies: melodrama.

The term “melodrama” literally means drama accompanied by music, which is why film is maybe the best most natural medium for it — aside from opera. What’s important to note is that the moral core of melodrama doesn’t intellectualize the story; it adds to the emotion by giving it the flavor of virtue. You know that Rose and Jack should be together, so when they get together it feels right and righteous. And when Jack dies at the end, it’s a heartbreak that makes the whole universe seem wicked.

Miiight be time for a rewatch.

Love it or hate it, we all know what Wes Anderson movies look like by now — the vibrant color palette, use of symmetry, lateral tracking shots, slow motion, etc. etc. In this video, Thomas Flight explores why Anderson uses these stylistic elements to tell affective and entertaining stories.

But what is at the core of those individual stylistic decisions? Why does Anderson choose those things? Why do all those things seem to form a very specific unified whole? And what function, if any, do they serve in telling the kinds of stories Wes wants to tell?

The sources for the video are listed in the description; one I particularly enjoyed was David Bordwell writing about planimetric composition. (via open culture)

This is a treat: a 30-minute video that celebrates the animations & animators that changed cinema, e.g. Yuri Norstein, Miyazaki, Fantasia, The Iron Giant, Persepolis, etc. — a full list of the filmography is available in the description. Absolutely stunning visuals on some of these. See also The 100 Sequences That Shaped Animation. (via open culture)

Ten years on from the release of Christopher Nolan’s Inception, Andrew Saladino of The Royal Ocean Film Society smartly traces the key influences of the film, rejecting the simplistic notion that Inception is just a rip-off of Paprika or The Matrix. Instead, he delves into long-standing themes in science fiction and other genres that Nolan is able to synthesize into something new. (Remember, everything is a remix.)

Also, kudos to Saladino to getting through an entire video on the ideas that influenced Inception without making an inception joke or reference, e.g. “Dark City incepted Nolan into including malleable architecture”. Clearly I could not have resisted.

The kids and I were talking about how slow motion video works the other day, so I was happy to see this new video from Phil Edwards detailing how the technique works and its history in cinema, from Eadweard Muybridge to Wes Anderson and from Seven Samurai to The Matrix.

I am an unabashed fan of slow motion; you can check out dozens of slow motion videos I have posted over the years, including this video of Alan Rickman dramatically drinking tea.

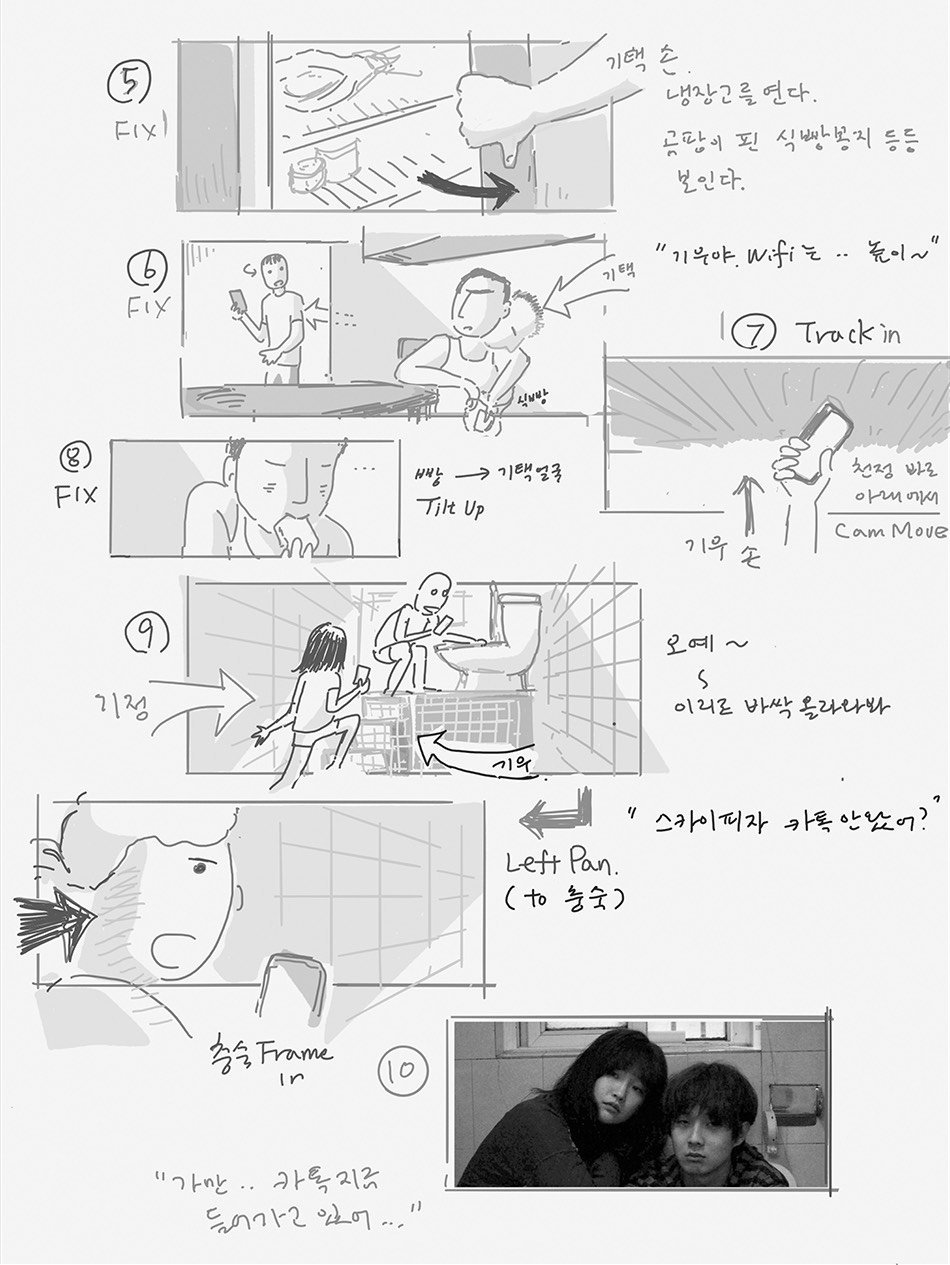

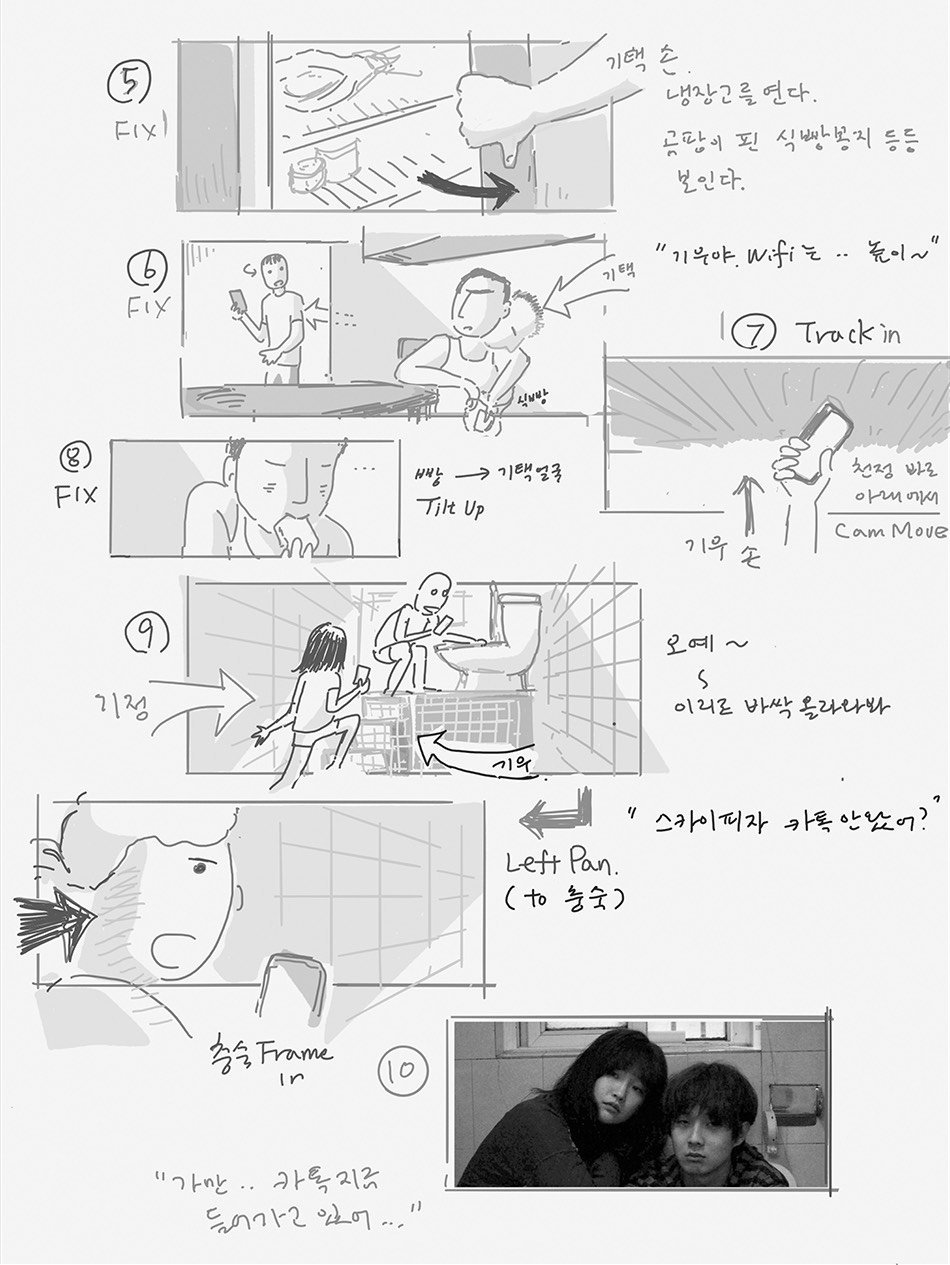

Before he begins filming any of his movies, director Bong Joon-ho draws out storyboards for every single shot of every single scene of the film. From an interview with Bong in 2017:

I’m always very nervous in my everyday life and if I don’t prepare everything beforehand, I go crazy. That’s why I work very meticulously on the storyboards. If I ever go to a psych ward or a psychiatric hospital, they’ll diagnose me as someone who has a mental problem and they’ll tell me to stop working, but I still want to work. I have to draw storyboards.

For his Oscar-winning Parasite, Bong has collected the storyboards into a 304-page graphic novel due out in mid-May: Parasite: A Graphic Novel in Storyboards.

Drawn by Bong Joon Ho himself before the filming of the Palme d’Or Award-winning, Golden Globe(R)-nominated film, these illustrations, accompanied by every line of dialog, depict the film in its entirety. Director Bong has also provided a foreword which takes the reader even deeper into the creative process which gave rise to the stunning cinematic achievement of Parasite.

The book has already been released in Korea, and Through the Viewfinder did a 5-minute video comparison of the storyboards with the filmed scenes for the peach fuzz montage scene (and another video of the flood scene).

Amazing. That’s a whole lotta film school packed into five minutes of video.

From Jon Lefkovitz, Sight & Sound is a feature-length documentary film about the legendary film editor and sound designer Walter Murch, who edited and did sound design for films like The Godfather, Apocalypse Now, and The Conversation.

This feature-length documentary, viewed and enjoyed by legendary film editor and sound designer Walter Murch himself (“The Conversation”, “Apocalypse Now”), was culled by Jon Lefkovitz from over 50 hours of Murch’s lectures, interviews, and commentaries.

That’s the whole film embedded above, available online for free. Here’s the trailer in case you need some prodding. I haven’t watched the whole film yet, but I’m definitely going to tuck into it in the next few days.

See also Worldizing — How Walter Murch Brought More Immersive Sound to Film.

I love echo - any kind of reverberation or atmosphere around a voice or a sound effect that tells you something about the space you are in.

That’s a quote from legendary film editor and sound designer Walter Murch. In the 70s, he pioneered a technique called worldizing, for which he used a mix of pristine studio-recorded and rougher set-recorded sounds to make a more immersive soundscape for theater audiences. He used it in The Godfather, Apocalypse Now, and American Graffiti:

George [Lucas] and I took the master track of the two-hour radio show with Wolfman Jack as DJ and played it back on a Nagra in a real space — a suburban backyard. I was fifty-or-so-feet away with a microphone recording that sound onto another Nagra, keeping it in sync and moving the microphone kind of at random, back and forth, as George moved the speaker through 180 degrees. There were times when microphone and speaker were pointed right at each other, and there were other times when they were pointed in completely opposite directions. So that was a separate track. Then, we did that whole thing again.

When I was mixing the film, I had three tracks to draw from. One of them was what you might call the “dry studio track” of the radio show, where the music was very clear and sharp and everything was in audio focus. Then there were the other two tracks which were staggered a couple of frames to each other, and on which the axis of the microphone and the speakers was never the same because we couldn’t remember what we had done intentionally.

1917 is the latest in a string of one-shot movies, where the action is presented in real-time and filmed to look as though it were done in one continuous take. This video takes a look at how director Sam Mendes, cinematographer Roger Deakins, and editor Lee Smith constructed the film. In this interview, Smith & Mendes say that the film contains dozens of cuts, with shots lasting anywhere from 39 seconds to 8 & 1/2 minutes. My favorite parts of the video are when they show the camera going from hand-held to crane to truck to cover single shots at a variety of speeds and angles. It’s really impressive.

But — does the effect work to draw the audience into the action? I saw 1917 last night and was distracted at times looking for the cuts and wondering how they seamlessly transitioned from a steadicam sort of shot to a crane shot. Maybe I’d read too much about it going in and distracted myself?

For the lastest episode of Nerdwriter, Evan Puschak reviews the history of movies about journalism and shows how the makers of Spotlight (and also All the President’s Men) show the often repetitive and tedious work required to do good journalism

I loved Spotlight (and All the President’s Men and The Post), but I hadn’t realized until just now how many of my favorite movies and TV shows of the last few years are basically adult versions of Richard Scarry’s What Do People Do All Day?

Speaking of, watching this video I couldn’t help but think that David Simon1 faced a similar challenge in depicting effective police work in The Wire. Listening to wiretapped conversations, sitting on rooftops waiting for drug dealers to use payphones, and watching container ships unloading are not the most interesting thing in the world to watch. But through careful editing, some onscreen exposition by Lester Freamon, and major consequences, Simon made pedestrian policing engaging and interesting, the heart of the show.

Riffing off a remark made by Guillermo del Toro that a director’s output is all part of the same movie, Andrew Saladino of The Royal Ocean Film Society looks at the many airships in Hayao Miyazaki’s films. What does the director’s continued use of flying machines tell us about filmmaking, technology, and everything else he’s trying to communicate though his films?

Pixar is always trying to push the envelope of animation and filmmaking, going beyond what they’ve done before. For the studio’s latest release, Toy Story 4, the filmmakers worked to inject as much reality into the animation as possible and to make it feel like a live-action movie shot with real cameras using familiar lenses and standard techniques. In the latest episode of Nerdwriter, Evan Puschak shares how they did that:

As I learned when I visited Pixar this summer,1 all of the virtual cameras and lenses they use in their 3D software to “shoot” scenes are based on real cameras and lenses. As the first part of the video shows, when they want two things to be in focus at the same time, they use a lens with a split focus diopter. You can tell that’s what they’re doing because you can see the artifacts on the screen — the blurring, the line marking the diopter transition point — just as you would in a live-action film.

They’re doing a similar thing by capturing the movement of actual cameras and then importing the motion into their software:

To get the motion just right for the baby carriage scene in the antique store for TS4, they took an actual baby carriage, strapped a camera to it, plopped a Woody doll in it, and took it for a spin around campus. They took the video from that, motion-captured the bounce and sway of the carriage, and made it available as a setting in the software that they could apply to the virtual camera.

Now, this is a really interesting decision on Pixar’s part! Since their filmmaking is completely animated and digital, they can easily put any number of objects in focus in the same scene or simply erase the evidence that a diopter was used. But no, they keep it in because making something look like it was shot in the real world with real cameras helps the audience believe the action on the screen. Our brains have been conditioned by more than 100 years of cinema to understand the visual language of movies, including how cameras move and lenses capture scenes. Harnessing that visual language helps Pixar’s filmmakers make the presentation of the action on the screen seem familiar rather than unrealistic.

Filmmaker Alfonso Cuarón has become the modern director most associated with the long take. In this video, The Royal Ocean Film Society takes a look at the long shots in his films, from Great Expectations to Gravity to Roma and considers how his approach evolves over time and what separates them from the use of long takes as “an obnoxious mainstream gimmick”.

All of the sequences discussed in the video are available to watch in full length here.

(I looked up Cuarón’s filmography and noticed he’s only directed 5 films in the past 20 years and only 8 total. I would have guessed more.)

Ben Burtt was the sound designer for the original Star Wars trilogy and was responsible for coming up with many of the movies’ iconic sounds, including the lightsaber and Darth Vader’s breathing.1 In this video, Burtt talks at length about how two dozens sounds from Star Wars were developed.

The base sound for the blaster shots came from a piece of metal hitting the guy-wire of a radio tower — I have always loved the noise that high-tension cables make. And I never noticed that Vader’s use of the force was accompanied by a rumbling sound. Anyway, this is a 45-minute masterclass in scrappy sound design.

See also: how the Millennium Falcon hyperdrive malfunction noise was made, exploring the sound design of Star Wars, and This Happy Dog Sounds Like a TIE Fighter.

2018’s most visually inventive movie was Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse. In this video, Danny Dimian, Visual Effects Supervisor, and Josh Beveridge, Head of Character Animation, talk about how they and their team created the look of the movie.

Two of my favorite details of the movie were the halftone patterns and the offset printing artifacts used to “blur” the backgrounds and fast-moving elements in some scenes. Borrowing those elements from the comic books could have gone wrong, it could have been super cheesy, they could have overused them in a heavy-handed way. But they totally nailed it by finding ways to use these techniques in service to the story, not just aesthetically.

Oh and the machine learning stuff? Wow. I didn’t know that sort of thing was being used in film production yet. Is this a common thing?

Update: Simon Willison did a Twitter thread that points to dozens of people who worked on Spider-Verse explaining how different bits of the film got made. What an amazing resource…kudos to Sony Animation for allowing their artists to share their process in public like this.

In the latest episode of Nerdwriter, Evan Puschak examines how Ian McKellen does a lot of heavy lifting with his eyes, especially in the Lord of the Rings trilogy. On his way there, I really liked Puschak’s lovely description of the physical craft of acting:

Part of that craft is understanding and gaining control of all the involuntary things we do when we communicate — the inflection of the voice, the gestures of the body, and the expressions of the face.

P.S. Speaking of actors being able to control their faces, have you ever seen Jim Carrey do wordless impressions of other actors? Check this out:

The Jack Nicholson is impressive enough but his Clint Eastwood (at ~1:15) is really off the charts. Look at how many different parts of his face are moving independently from each other as that jiggling Jello mold eventually gather into Eastwood’s grimace. Both McKellen and Carrey are athletic af in terms of their body control in front of an audience or camera.

Jonathan Demme’s The Silence of the Lambs is one of the finest psychological thrillers ever made. In the episode of the always-illuminating Lessons from the Screenplay, the team analyzes a scene from the film with Hannibal Lecter and Clarice Starling that demonstrates how effective scenes follow the same three act structure as entire movies/books/stories do.

The Lessons team also did a podcast episode about the differences between the screenplay for the film and the book that inspired it.

Using screenwriter Danny Rubin’s book How To Write Groundhog Day as a guide, Lessons from the Screenplay examines how the protagonist in the Bill Murray comedy classic is forced by his circumstances to undergo the hero’s journey and emerging at the end having changed. This passage from Rubin’s book sets the stage:

The conversation I was having with myself about immortality was naturally rephrased in my mind as a movie idea: “Okay, there’s this guy that lives forever…” Movie stories are by nature about change, and if I were to test the change of this character against an infinity of time, I’d want him to begin as somebody who seemed unable to change.

We’ve all seen movies where the change the protagonist undergoes does not seem earned and it makes the whole movie seem phony and hollow. One of the things that makes Groundhog Day so great is that a person who starts out genuinely horrible at the beginning transforms into a really good person by the end and the audience completely buys it. At any point along the way, the story could very easily jump off the rails of credulity, but it never does. A nearly perfect little movie.

Newer posts

Older posts

Socials & More