Slow Motion Surfing

You know what’s pretty? Big waves and surfing in slow motion. Take a break and relax at 1000 fps with this mesmerizing video.

The Hans Zimmer soundtrack only adds to the effect. (via ★interesting)

This site is made possible by member support. 💞

Big thanks to Arcustech for hosting the site and offering amazing tech support.

When you buy through links on kottke.org, I may earn an affiliate commission. Thanks for supporting the site!

kottke.org. home of fine hypertext products since 1998.

You know what’s pretty? Big waves and surfing in slow motion. Take a break and relax at 1000 fps with this mesmerizing video.

The Hans Zimmer soundtrack only adds to the effect. (via ★interesting)

From Grantland’s 30 for 30 Shorts series, a short film on former major league catcher Mackey Sasser and how he lost the ability to throw the ball back to the pitcher.

[I took the video out because someone at ESPN/Grantland is idiot enough to think that, by default, videos embedded on 3rd-party sites should autoplay. Really? REALLY!? Go here to watch instead.]

I remember Sasser (I had his rookie card) but had kinda stopped paying attention to baseball by the time his throwing problem started; I had no idea it was so bad. The video of him trying to throw is painful to watch. According to the therapists we see working with Sasser in the video, unresolved mental trauma (say, from childhood) builds up and leaves the person unable to resolve something as seemingly trivial as a small problem throwing a ball back to the pitcher. I’ve read and written a lot about this sort of thing over the years.

Watch as Stig Severinsen, aka The Man Who Doesn’t Breathe, swims underwater amongst icebergs. Beautiful.

Severinsen is currently the world’s record holder for the longest time holding a breath at 22 minutes. 22! I barely breathed myself while watching this video of his record breaking attempt. (via devour)

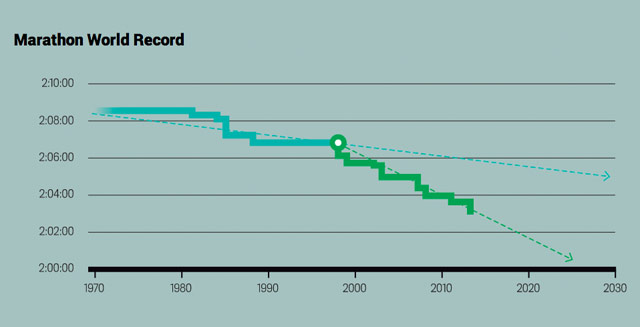

I am not a runner so I didn’t think I would find this exploration into the conditions under which a 2-hour marathon could occur that interesting. I was incorrect.

Between 1990 (the first year in which data was available) and 2011, the average male marathoner ranked in the top 100 that year shrank by 1.3 inches and 7.5 pounds. Smaller runners have less weight to haul around, yes. But they’re also better at heat dissipation; thanks to greater skin surface area relative to their weight, they can sustain higher speeds (and thus, greater internal heat production) without overheating and having to slow down. Despite our sub-two runner’s short frame, he’ll also have disproportionately long legs that help him cover ground and unusually slender calves that require less energy to swing than heavier limbs.

Runners shed heat through their skin, so bigger runners should have an advantage, right? Indeed, a 6’ 3” marathoner can dissipate 32 percent more heat than a 5’ 3” athlete with the same BMI. But heat generation rises faster in bigger runners because mass increases quicker than skin area. So at the same effort, the 6’ 3” guy ends up producing 42 percent more heat than his shorter peer-and overheating sooner.

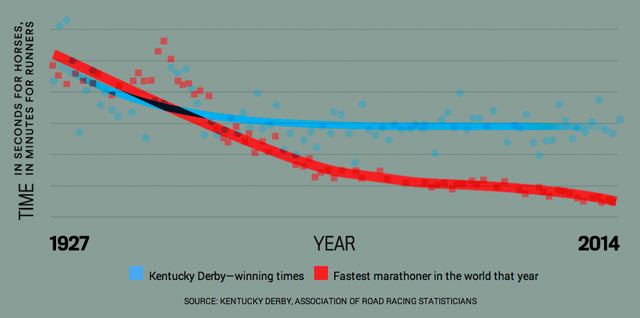

The piece includes a favorite old chestnut of mine, man vs. horse:

Horses are still much quicker at distance, but humans are still improving.

Update: At the 2014 Berlin Marathon, Dennis Kimetto set a new world record, lowering the mark under 2:03 for the first time. (via @brzeski)

A Euro 2016 qualifying match between Albania and Serbia was abandoned today after a drone flying a banner with a map of Kosovo and the Albanian flag on it hovered over the pitch.

Tensions increased further when the flag was snared by Serbia’s Stefan Mitrovic, who then pulled on the strings connecting it to the drone. He was immediately confronted by Albanian players, and a shoving match ensued.

The match was abandoned after a lengthy delay. At the recommendation of UEFA, no Albanian fans were allowed into the stadium for the match in Belgrade due to tensions between the two nations. Kosovo, where the population includes both ethnic Serbs and Albanians, declared its independence from Serbia in 2008, a declaration that the Serbians dispute. Nick Ames wrote a soccer-centric take on the tensions between the two nations.

It comes down, really, to Kosovo — and that is a phrase that can be applied as shorthand for Serbian-Albanian relations as a whole. As Tim Judah writes in his seminal history, The Serbs: “So poisoned is the whole subject of Kosovo that when Albanian or Serbian academics come to discuss its history, especially its modern history, all pretence of impartiality is lost.”

Kosovo, situated to the south of Serbia and the north-east of Albania, declared independence in 2008 having previously been part of Serbia. The Serbs still regard it as their own, but it is recognised by 56 percent of UN member states and its ethnic makeup is, depending on which side you refer to, overwhelmingly Albanian. (It’s worth noting that figures vary wildly.)

The emotional significance goes as far back as 1389, when the Serbs were defeated by the Ottoman army in the Battle of Kosovo, which took place near its modern-day capital, Pristina. It has been much-mythologised in Serbian history. Far more recently, memories of the 1998-99 Kosovo War — an appallingly brutal fight for the territory from which it has not really recovered — still run deep.

FYI: the YouTube embed above was recorded off of a TV…if you’re in the US, the ESPN story has better video.

When he was 17, Eric Kester was a ball boy for the Chicago Bears and saw all the stuff you don’t hear about on TV or even on blogs.

I lay awake at night wondering how many lives were irreparably damaged by my most handy ball boy tool: smelling salts. On game days my pockets were always full of these tiny ammonia stimulants that, when sniffed, can trick a brain into a state of alertness. After almost every crowd-pleasing hit, a player would stagger off the field, steady himself the best he could, sometimes vomit a little, and tilt his head to the sky. Then, with eyes squeezed shut in pain, he’d scream “Eric!” and I’d dash over and say, “It’s O.K., I’m right here, got just what you need.”

And from Vice, the story of former NFL running back Gerald Willhite:

Memory loss is just one of the problems that plague Gerald Willhite, 55. Frustration, depression, headaches, body pain, swollen joints, and a disassociative identity disorder are other reminders of his seven-season (1982-88) career with the Denver Broncos, during which he said he sustained at least eight concussions.

“I think we were misled,” Willhite said from Sacramento. “We knew what we signed up for, but we didn’t know the magnitude of what was waiting for us later.”

When Willhite read about the symptoms of some former players who were taking legal action against the NFL, he thought “Crap, I got the same issues.” He decided to join the lawsuit that claimed the league had withheld information about brain injuries and concussions. He feels that the $765 million settlement, announced last summer and earmarked for the more than 4,000 players in the lawsuit, is like a “Band-Aid put on a gash.”

Still haven’t watched any NFL this year. (via @arainert)

I’ve posted quite a few skateboarding videos here over the years and they all have their share of amazing tricks, but the shit Bob Burnquist pulls on his massive backyard MegaRamp in this video is crazy/incredible. My mouth dropped open at least four times while watching. I rewatched the trick at 2:50 about 10 times and still can’t believe it’s not from a video game. (via @bryce)

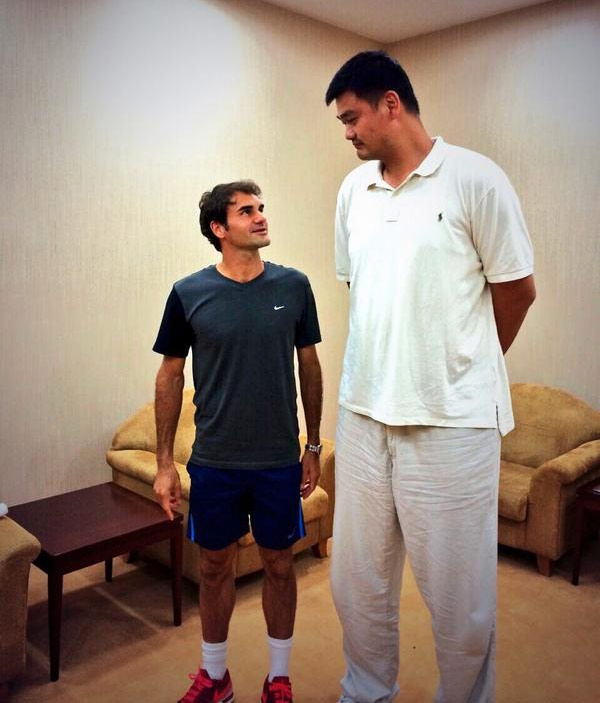

Possible captions for this photo: Honey, I Shrunk the Federer. Federer just drank some of Alice’s Drink Me potion. Pocket Roger. Yao Ming is a very large man.

As I’ve written before, after the World Cup in 2010, I wanted to keep watching soccer but didn’t quite know how club soccer worked or anything about the various teams. I wish I’d had this book then: Club Soccer 101. It’s a guide to 101 of the most well-known teams from leagues all over the world.

The book covers the history of European powerhouses like Arsenal, Barcelona, Bayern Munich, Chelsea, Inter Milan, Manchester United, Paris Saint-Germain, and Real Madrid; historic South American clubs like Boca Juniors, Corinthians, Penarol, and Santos; and rising clubs from Africa, Asia, and America, including such leading MLS clubs as LA Galaxy, New York Red Bulls, and Seattle Sounders. Writing with the passion and panache of a deeply knowledgeable and opinionated fan, Luke Dempsey explains what makes each club distinctive: their origins, fans, and style of play; their greatest (and most heartbreaking) seasons and historic victories and defeats; and their most famous players — from Pelé, Eusébio, and Maradona to Lionel Messi, Wayne Rooney, and Ronaldo.

Lionel Messi made his debut for FC Barcelona 10 years ago. At Grantland, Brian Phillips assesses his career thus far.

The irony of that goal against Getafe, in retrospect, is that he’s not the next Maradona; he’s nothing like Maradona. Maradona was all energy, right on the surface; watching Messi is like watching someone run in a dream. Like Cristiano Ronaldo, Maradona jumped up to challenge you; if you took the field against him, he wanted to humiliate you, to taunt you. Messi plays like he doesn’t know you’re there. His imagination is so perfectly fused with his technique that his assumptions can obliterate you before his skill does.

He has always seemed oddly nonthreatening for someone with a legitimate claim to being the best soccer player in history. He seems nice, and maybe he is. (He goes on trial for tax evasion soon; it is impossible to believe he defrauded authorities on purpose, because it is impossible to believe that he manages his finances at all.) On the pitch, though, this is deceptive. It’s an artifact of his indifference to your attention. He doesn’t notice whether or not you notice. His greatness is nonthreatening because it is so elusive, even though its elusiveness is what makes it a threat.

Messi is only 27, holds or is within striking distance of all sorts of all-time records, and I’m already sad about his career ending. This is big talk, perhaps nonsense, but Messi might be better at soccer than Michael Jordan was at basketball. I dunno, I was bummed when Jordan retired (well, the first two times anyway), but with Messi, thinking about his retirement, it seems to me like soccer will lose something special that it will never ever see again.

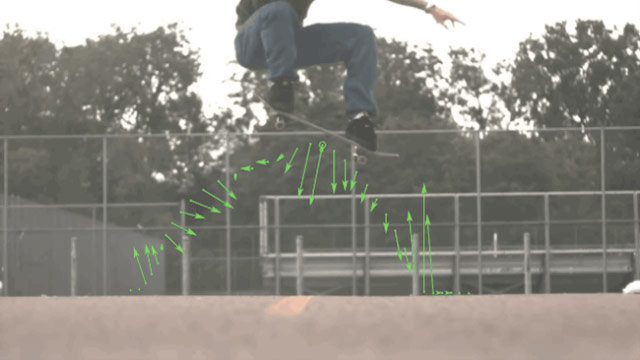

This is fun…Aatish Bhatia maps out the forces and motions involved in doing an ollie on a skateboard.

It’s a neat piece of science art, and it also tells us something interesting. The arrows show us that the force on the skateboard is constantly changing, both in magnitude as well as in direction. Now the force of gravity obviously isn’t changing, so the reason that these force arrows are shrinking and growing and tumbling around is that the skater is changing how their feet pushes and pulls against the board. By applying a variable force that changes both in strength and direction, they’re steering the board.

Is this the first surrealist free diving video? I wasn’t sure and then Superman showed up.

Thirteen Ways of Looking at Greg Maddux is not really a story about Greg Maddux. Or sports. It’s about Jeremy Collins’ friend Jason Kenney, demons, self-control, determination, friendship, competitiveness, and loss.

Jason kept a picture of Maddux above his desk in our dorm room at Young Harris College in the north Georgia mountains. A beautiful athlete, the best on campus, Jason played only intramurals and spent serious time at his desk. A physics workhorse and calculus whiz, he kept Maddux’s image at eye-level.

Shuffling and pardoning down the aisle to our seats, Jason stopped and squeezed my shoulder. “Look,” he said.

Maddux strode toward home, hurling the ball through the night.

It’s 2014. I’m thirty-seven. My wife and daughter are both asleep. I’m a thousand miles from the stadium-turned-parking-lot. On YouTube, Kenny Lofton of the American League Champion Cleveland Indians looks at the first pitch for a ball. Inside, low. I don’t remember the call. I remember all of us standing, holding our breath. Then I remember light. Thousands of lights. Waves of tiny diamonds. The whole stadium flashing and Jason, who would die five months later on the side of a south Georgia highway, leaning into my ear and whispering, “Maddux.”

Great, great story. As Tom Junod remarked on Twitter, “Every once in a while, a writer throws everything he’s got into a story. This is one of those stories.”

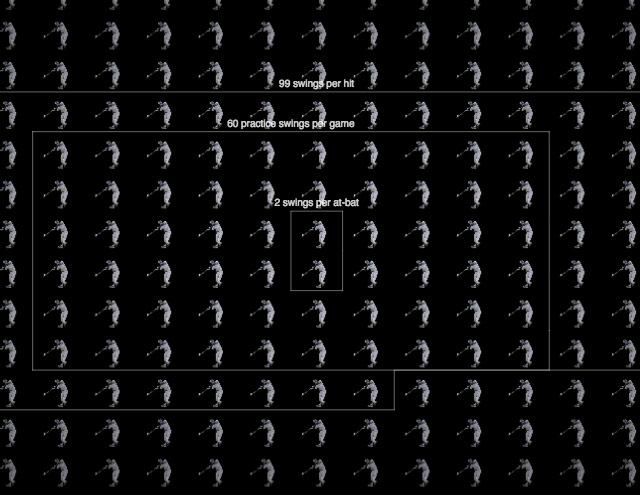

Love this New York Times visualization of how many times Derek Jeter has swung a bat during his career. This is like Powers of Ten, but with Derek Jeter bat swings.

This goal by AC Milan’s Jeremy Menez against Parma over the weekend is just beyond:

No-look backheel. Jeebus.

Life-long NFL football fan Steve Almond recently wrote a book called Against Football in which he details why he is no longer watching the game he loves. Ian Crouch talked with Almond for the New Yorker.

Any other year, Steve Almond would have seen the play. But, after forty years of fandom, he’s quit the N.F.L. In his new book, “Against Football,” Almond is plain about what he considers the various moral hazards of the game: “I happen to believe that our allegiance to football legitimizes and even fosters within us a tolerance for violence, greed, racism, and homophobia.”

This part resonated most with me:

Even a casual N.F.L. fan can recognize that this is a particularly opportune time for a Raiders fan to stop watching football. The team is terrible. I asked Almond about that. “If the Raiders were really good, I might not have written the book,” he said. “How fucked up is that? It’s true, I love them. I see those colors, and it’s me.” For Almond, his struggle to confront his own hypocrisy is exactly the point: proof of football’s insidiousness, of its ominous power.

“Football somehow hits that Doritos bliss point,” he told me. “It’s got the intellectual allure of all these contingencies and all this strategy, but at the same time it is so powerfully connecting us to the intuitive joys of childhood, that elemental stuff: Can you make a miracle? Can you see the stuff that nobody else sees? And most of us can’t, but we love to see it. And I don’t blame people for wanting to see it. I love it, and I’m going to miss it.”

I’ve been a steadfast fan of NFL football for the past 15 years. Most weekends I’d catch at least two or three games on TV. Professional football lays bare all of the human achievement + battle with self + physical intelligence + teamwork stuff I love thinking about in a particularly compelling way. But for a few years now, the cons have been piling up in my conscience: the response to head injuries, the league’s nonprofit status, the homophobia, and turning a blind eye to the reliance on drugs (PEDs and otherwise). And the final straw: the awful terrible inhuman way the league treats violence against women.

It’s overwhelming. Enough is enough. I dropped my cable subscription a few months ago and was considering getting it again to watch the NFL, but I won’t be doing that. Pro football, I love you, but we can’t see each other anymore. And it’s definitely you, not me. Call me when you grow up.

Update: Chuck Klosterman recently tackled (*groan*) this issue in the NY Times Magazine: Is It Wrong to Watch Football?

My (admittedly unoriginal) suspicion is that the reason we keep having this discussion over the ethics of football is almost entirely a product of the sport’s sheer popularity. The issue of concussions in football is debated exhaustively, despite the fact that boxing — where the goal is to hit your opponent in the face as hard as possible — still exists. But people care less about boxing, so they worry less about the ethics of boxing. Football is the most popular game in the United States and generates the most revenue, so we feel obligated to worry about what it means to love it. Well, here’s what it means: We love something that’s dangerous. And I can live with that.

Ta-Nehisi Coates quit watching back in 2012 after Junior Seau died.

I’m not here to dictate other people’s morality. I’m certainly not here to call for banning of the risky activities of consenting adults. And my moral calculus is my own. Surely it is a man’s right to endanger his body, and just as it is my right to decline to watch. The actions of everyone in between are not my consideration.

Same here. I don’t feel any sense of judgment or righteousness about this. Just the personal loss of a hobby I *really* enjoyed. (via @campbellmiller & @Godzilla07)

It turns out that this close-up video of slow motion skateboard tricks is all I’ve ever wanted out of life.

I had no idea that’s what they were doing down there. It’s a symphony of footwork!

Anthony Richardson (previously, previouslyer, previouslyest) describes a NASCAR race from the British perspective.

Now for the bumper view! Wow, the easiest way to work out what on Earth is going on. Oh, the car’s giving the one in front a little sniff. Ah, they’re a bit like dogs, aren’t they? Petrol dogs.

That’s the somewhat unusual name of a feature-length documentary about world-class stone skippers. Here’s the trailer:

I love skipping stones. When I see flat water and flat rocks, I can’t not do it. They have to change that name though. They were likely going for “Jiro Dreams of Sushi” but really missed the mark. Oh, and they’re raising funds on Kickstarter to finish the film.

The zen art of stone skipping meets the competitive nature of mankind in this feature-length documentary. Set in the world of professional stone skipping, this film will examine the competitive nature of mankind. World Records will be tested, rivalries will fester, and a sport will rise from the ashes of obscurity.

Update: The full-length movie is now available for rent or purchase on Vimeo.

Michael Jordan and Kobe Bryant played against each other in only eight NBA games, but none of the games took place with both players in their prime. Their first few meetings, dominated by Jordan, happened during Kobe’s first and second NBA seasons, when he was an impulsive and unpolished teen. Their final meetings, dominated by Bryant, found an out-of-retirement Jordan on the hapless Washington Wizards, pushing 40 years old.

But more than any other two marquee players in NBA, Jordan and Kobe have played with very similar styles. Like almost identically similar, as this video clearly shows:

The first 15 seconds of the video is a fantastic piece of editing, stitching together similar moves made by each player into seamless single plays. And dang…even the tongue wagging thing is the same. How many hours of Jordan highlight reels did Kobe watch growing up? And practicing moves in the gym?

As an aside, and I can’t believe I’m saying such a ridiculous thing in public, but I can do a pretty good MJ turnaround fadeaway. I mean, for a 6-foot-tall 40-year-old white guy who doesn’t get a lot of exercise and has never had much of a vertical leap. I learned it from watching Jordan highlights on SportsCenter and practicing it for hundreds of hours in my driveway against my taller next-door neighbor. I played basketball twice in the past month for the first time in years. Any skills I may have once had are almost completely gone…so many airballs and I couldn’t even make a free throw for crying out loud. Except for that turnaround. That muscle memory is still intact; the shots were falling and the whole thing felt really smooth and natural. I think I’ll still be shooting that shot effectively into my 70s. (via devour)

Erik Malinowski takes a baseball commercial that used to air late nights on ESPN in the ’90s and ’00s, and uses it to trace the effect of technology on sports.

“He was the first guy I ever knew who used video as a training device in baseball,” says Shawn Pender, a former minor-league player who would appear in several of Emanski’s instructional videos. “There just wasn’t anyone else who was doing what he did.”

It’s also something of a detective story, since its subject Tom Emanski has virtually fallen off the face of the earth:

Fred McGriff is surely correct that nearly two decades of video sales — first through TV and radio and now solely through the internet — made Emanski a very wealthy man, but this perception has led to some rather outlandish internet rumors.

According to one, the Internal Revenue Service investigated Emanski in 2003 for unpaid taxes and, in doing so, somehow disclosed his estimated net worth at around $75 million. There’s no public record of such an investigation ever having taken place or been disclosed, and an IRS spokesman for the Florida office would say only that the agency is “not permitted to discuss a particular or specific taxpayer’s tax matter or their taxes based on federal disclosure regulations and federal law.”

Yesterday, I was looking for a GIF of two people missing a high-five (as one does) and the top hits I got back were all of New England Patriots quarterback Tom Brady.

I thought, “the three-time Super Bowl winner and one of his wide receivers trying to high-five and missing each other’s hands? That’s pretty funny!” Oh no. What is funnier still is Brady trying to high-five one or more of his teammates and the other players totally ignoring him. What’s even funnier than that? This has happened over and over again.

Against the Ravens:

Against the Saints:

And against the Steelers. (These are all just from last season, and all Patriots wins, by the way):

Nobody likes a pity five.

NFL Films even made a “Give Brady a high-five” video, which led to this spoof PSA:

If Glenn Burke and the 1977 Dodgers show us the original spirit of the high-five, Tom Brady and the 2013 Patriots show us that the high-five evangelist’s work is never done.

(via Boston.com and SB Nation)

For the latest installment of Grantland’s 30 for 30 short documentary series, a story on the genesis of the high five and what happened to one of its inventors. This video is chock full of amazing vintage footage of awkward high fives. [Weird aside: The sound on this video is only coming out of the left channel. Is that a subtle homage to the one-handed gesture or a sound mixing boner?]

The evidence has mounted to such an extent that Brian Windhorst of ESPN has written an article about LeBron James’ fantastic memory.

So what does it mean? What it seems to suggest — at least the part of it that James will discuss — is that if you give up the baseline to James on a drive in November 2011 and he’s playing against you in March 2013, the Heat small forward will remember it. It means that if you tried to change your pick-and-roll coverage in the middle of the fourth quarter of the 2008 playoffs, he’ll be ready for you to try it again in 2014, even if you’re coaching a different team. It also means that if you had a good game the last time you played against Milwaukee because James got you a few good looks in the first quarter, the next time you play the Bucks you can count on James looking for you early in the game. Because, you know, the memory never forgets.

“I can usually remember plays in situations a couple of years back — quite a few years back sometimes,” James says. “I’m able to calibrate them throughout a game to the situation I’m in, to know who has it going on our team, what position to put him in.

“I’m lucky to have a photographic memory,” he will add, “and to have learned how to work with it.”

Which sounds great, right? Except that thinking’s best friend is often overthinking.

Consider what you know of the 2011 NBA Finals. And now consider it, instead, like this: In what will likely be remembered as the low point of his career, James is miserable for several games against the Dallas Mavericks — including a vitally important Game 4 collapse when he somehow scores just eight points in 46 minutes. At times during that game it appears as if James is in a trance.

“What is he thinking?” the basketball world wonders.

James — with two titles and counting, and four straight trips to the Finals — can admit today what he’s thinking in 2011: He’s thinking of everything. Everything good, and everything bad. In 2011, he isn’t just playing against the Mavs; he’s also battling the demons of a year earlier, when he failed in a series against the Boston Celtics as the pressure of the moment beat him down. It’s Game 5 of the 2010 Eastern Conference semifinals, and it is, to this point, perhaps the most incomprehensible game of James’ career. His performance is so lockjawed, so devoid of rhythm, the world crafts its own narrative, buying into unfounded and ridiculous rumors because they seem more plausible than his performance.

I’ve probably said this a million times, but my favorite aspect of sports is the mental game, each athlete’s battle with her/himself: from Shaq’s dreamful attraction to Allen Iverson’s visualization in lieu of practice to better living through self deception to Roger Federer’s conservation of concentration to free diver Natalia Molchanova’s attention deconcentration to deliberate practice to relaxed concentration. James taming his tide of memories fits right in.

If you enjoyed the World Cup but don’t know how to proceed into the seemingly impenetrable world of soccer, with its overlapping leagues, cups, and tournaments, this guide from Grantland is for you.

Just because the World Cup is over doesn’t mean soccer stops. Soccer never stops; that’s one of its biggest appeals. There are so many different teams, leagues, club competitions, and international tournaments that, if you want to, you can always find someone to cheer for or some team to root against. It can also be a bit daunting to wade into without any experience. Luckily, you have me, your Russian Premier League-watching, tactics board-chalking, Opta Stats-devouring Gandalf, to help you tailor your soccer-watching habits. And now I will answer some completely made-up questions to guide you along your soccer path.

This was basically my situation after the 2010 World Cup, a soccer fan with nowhere to direct his fandom. What I did was:

1. Picked a player I enjoyed watching (Messi) and started following his club team (FC Barcelona) and, to a somewhat lesser degree, the league that team played in (La Liga). I know a lot more cities in Spain than I used to.

2. Watched as many Champions League matches as I could every year, again more or less following Barcelona.

3. Got into UEFA European Championship, which is basically the World Cup but just for Europe. It’s held every four years on a two-year stagger from the WC and the next one is in 2016 in France, which, I’m realizing just now, I should try to attend.

I also watched a few Premier League matches here and there…it’s a great league with good competition. What I didn’t do is follow any MLS or the USMNT, although after this WC, I might give the Gold Cup and Copa America tournaments some more attention. And qualifying matches for the 2018 World Cup start in mid-2015…soccer never ends.

Somehow I lived in WI for the first 17 years of my life, was a Brewers fan for many of those years, and never realized the old Brewers logo contained the letters “m” and “b” hidden in the ball and glove.

Wow. If your mind is blowing right now too, there’s a Facebook group we can join together: Best Day of My Life: When I Realized the Brewers Logo Was a Ball and Glove AND the Letters M and B. (via kathryn yu)

ps. If you’ve somehow missed the hidden arrow in the FedEx logo, here you go. Best kind of natural high there is.

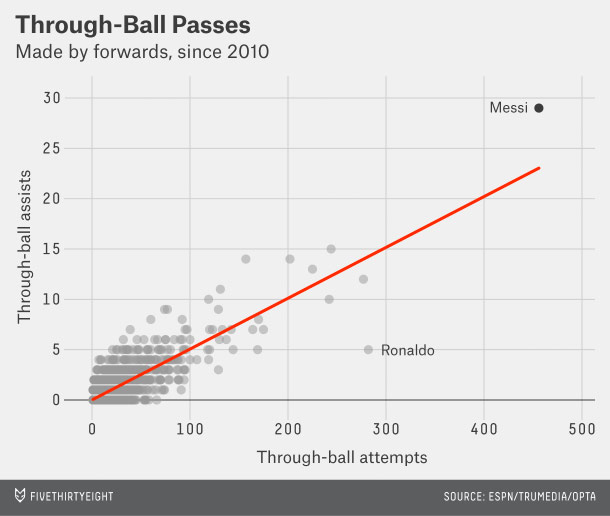

An open-and-shut case from FiveThirtyEight: Lionel Messi is far and away the best player in football. Ronaldo is the only player who is close and he’s not even all that close.

By now I’ve studied nearly every aspect of Messi’s game, down to a touch-by-touch level: his shooting and scoring production; where he shoots from; how often he sets up his own shots; what kind of kicks he uses to make those shots; his ability to take on defenders; how accurate his passes are; the kind of passes he makes; how often he creates scoring chances; how often those chances lead to goals; even how his defensive playmaking compares to other high-volume shooters.

And that’s just the stuff that made it into this article. I arrived at a conclusion that I wasn’t really expecting or prepared for: Lionel Messi is impossible.

It’s not possible to shoot more efficiently from outside the penalty area than many players shoot inside it. It’s not possible to lead the world in weak-kick goals and long-range goals. It’s not possible to score on unassisted plays as well as the best players in the world score on assisted ones. It’s not possible to lead the world’s forwards both in taking on defenders and in dishing the ball to others. And it’s certainly not possible to do most of these things by insanely wide margins.

But Messi does all of this and more.

The piece is chock-full of evidential graphs of how much of an outlier Messi is among his talented peers:

One of my favorite things that I’ve written about sports is how Lionel Messi rarely dives, which allows him to keep the advantage he has over the defense.

After Michael Lewis wrote Moneyball in 2003 about the Oakland A’s, their general manager Billy Beane, and his then-unorthodox and supposedly superior managerial strategy, a curious thing happened: the A’s didn’t do that well. They went to the playoffs only twice between 2003 and 2011 and finished under .500 four times. Teams like the Red Sox, who adopted Beane’s strategies with the punch of a much larger payroll, did much better during those years.

But Beane hung in there and has figured out how to beat the big boys again, with two first place in 2012 & 2013 and the best record in the majors this year so far. Will Leitch explains how.

First, don’t spend a lot on a little; spend a little on a lot.

The emotional through-line of Moneyball is Beane learning from his experience as a failed prospect and applying it to today’s game. The idea: Scouts were wrong about him, and therefore they’ll be wrong about tons of guys. Only trust the numbers.

That was an oversimplification, but distrusting the ability of human beings to predict the future has been the centerpiece of the A’s current run. This time, though, the A’s aren’t just doubting the scouts; they’re also skeptical that statistical analysis can reliably predict the future (or that their analysis could reliably predict it better than their competitors). Instead, Beane and his front office have bought in bulk: They’ve brought in as many guys as possible and seen who performed. They weren’t looking for something that no one else saw: They amassed bodies, pitted them against one another, were open to anything, and just looked to see who emerged. Roger Ebert once wrote that the muse visits during the act of creation, rather than before. The A’s have made it a philosophy to just try out as many people as possible — cheap, interchangeable ones — and pluck out the best.

There haven’t been many good books written about soccer, but here are eleven of them worth your time. Franklin Foer’s How Soccer Explains the World: An Unlikely Theory of Globalization looks especially interesting.

A groundbreaking work — named one of the five most influential sports books of the decade by Sports Illustrated — How Soccer Explains the World is a unique and brilliantly illuminating look at soccer, the world’s most popular sport, as a lens through which to view the pressing issues of our age, from the clash of civilizations to the global economy.

Foer is one of the contributors, alongside authors Aleksandar Hemon and Karl Ove Knausgaard, to the New Republic’s excellent World Cup coverage.

Watch as two players from the Japanese national soccer team try to score against 55 kids.

The kids had two opportunities to stop the pro players, once with 33 players and the second time with 55 players. This didn’t turn out how I expected, given how a similar stunt involving fencing ended.

This was posted on Marginal Revolution a few days ago and garnered several interesting comments about how much better professional athletes are than us regular folk. Here are a few:

Rugby: I played against an international player once. Watching him play, I’d seen a chap who ran in straight lines, a strong tackler with a weak kick. Playing against him revealed him to be skillful, agile and possessed of a howitzer kick.

Back in the 1980s a friend was watching a pickup basketball game in Boston and reported what happened when a player from the Celtics showed up. He was so much faster, more athletic, and more agile than the other players that it seemed like he was playing a different sport. The player turned out to be Scott Wedman, who by that time was old and slow by NBA standards, and mainly hung around the 3-point line to shoot outside shots after the defense had collapsed on Bird, McHale, et al. But compared to non-NBA players, he was Michael Jordan (or LeBron James).

My U-19 team (we were very good by local standards) had a practice with the New Zealand All Blacks, who were on some sort of tour. It was like they were from a different planet. I stood no chance of containing, or conversely getting past, the smallest of them under almost any circumstance.

Back in the olden thymes I was a pretty good baseball player. Early in my high school career I got the chance to catch a AAA pitcher. I went into thinking I would have no trouble. The first pitch was on top of me so fast I was knocked off balance. It took a bunch of pass balls before I got used to how to handle his breaking stuff.

The result in the video might also shed some light on the question of choosing to fight one horse-sized duck or 100 duck-sized horses.

Stay Connected