kottke.org posts about books

The New Yorker pulled one over on me. The recent Summer Fiction Issue contained a piece (not online) by novelist Haruki Murakami which I skimmed right over, thinking it was a piece of short fiction. Turns out it’s an excerpt from Murakami’s memoir, What I Talk About When I Talk About Running, a book detailing how he became a novelist and an avid runner.

In other words, you can’t please everybody.

Even when I ran the club, I understood this. A lot of the customers came to the club. If one of out ten enjoyed the place and decided to come again, that was enough. If one out of ten was a repeat customer, then the business would survive. To put it another way, it didn’t matter if nine out of ten people didn’t like the club. Realizing this lifted a weight off my shoulders. Still, I had to make sure that the one person who did like the place really liked it. In order to do that, I had to make my philosophy absolutely clear, and patiently maintain that philosophy no matter what. This is what I learned from running a business.

After “A Wild Sheep Chase,” I continued to write with the same attitude that I’d developed as a business owner. And with each work my readership — the one-in-ten repeaters — increased.

In addition to writing his dozen novels, Murakami has also run 26 marathons. The Economist calls the book both puzzling and intriguing and stops just short of recommending it, while the A.V. Club really liked it. The Observer has another excerpt from the book about the author’s ultramarathon attempt.

From an article on a new book written by a woman whose ex-boyfriend has been stalking her for more than a decade, a curious phrase: micro-tampering.

No matter how many times Ms. Brennan changed the locks, she writes, her apartment was entered and subtly rearranged. “I find a bar of soap from the second-floor bathroom on the third-floor kitchen counter,” she writes. “A teaspoon from a kitchen drawer lies on the middle of my bed.”

Update: See also: gaslighting. (thx, alex)

A thoughtful letter from a librarian to a woman who wanted a book depicting gay marriage removed from the children’s section of the library.

I fully appreciate that you, and some of your friends, strongly disagree with its viewpoint. But if the library is doing its job, there are lots of books in our collection that people won’t agree with; there are certainly many that I object to. Library collections don’t imply endorsement; they imply access to the many different ideas of our culture, which is precisely our purpose in public life.

Illustrator Kean Soo and writer Kevin Fanning created a book about the internet for babies: Baby’s First Internet.

Do not stop to think or edit:

You must be the first who said it.

You heard a brand-new band? What luck!

You’ll be the first to say they suck.

I’d read it to Ollie but do 1-year-olds understand cautionary tales?

NY Times columnist David Carr has written a book about his days as a junkie who cleaned himself up only when twin daughters came into his life. The Times has a lengthy excerpt; it’s possibly the best thing I’ve read all week.

If I said I was a fat thug who beat up women and sold bad coke, would you like my story? What if instead I wrote that I was a recovered addict who obtained sole custody of my twin girls, got us off welfare and raised them by myself, even though I had a little touch of cancer? Now we’re talking. Both are equally true, but as a member of a self-interpreting species, one that fights to keep disharmony at a remove, I’m inclined to mention my tenderhearted attentions as a single parent before I get around to the fact that I hit their mother when we were together. We tell ourselves that we lie to protect others, but the self usually comes out looking damn good in the process.

Carr’s book is not the conventional memoir. Instead of relying on his spotty memory from his time as a junkie, he went out and interviewed his family, friends, enemies, and others who knew him at the time to get a more complete picture.

A former colleague interviewed Carr two years ago in Rake Magazine. (via vsl)

After publishing his first book, Mark Hurst offers some tips for would-be authors, painting a not-so-rosy picture of the publishing industry in the process.

You may see now the author’s dilemma. Publishers and bookstores are in it for the money. But you, the author, can’t be in it for the money - it doesn’t pay enough. You should write a book because you believe in it. And that’s the trouble: what you love isn’t necessarily what publishers believe will sell. If you can find a topic that you love and that will sell in the market, well then, go forth and type. You’re one of the lucky ones.

A book by the proprietor of the Waiter Rant blog is finally due out at the end of July.

According to The Waiter, eighty percent of customers are nice people just looking for something to eat. The remaining twenty percent, however, are socially maladjusted psychopaths. Waiter Rant offers the server’s unique point of view, replete with tales of customer stupidity, arrogant misbehavior, and unseen bits of human grace transpiring in the most unlikely places. Through outrageous stories, The Waiter reveals the secrets to getting good service, proper tipping etiquette, and how to keep him from spitting in your food. The Waiter also shares his ongoing struggle, at age thirty-eight, to figure out if he can finally leave the first job at which he’s truly thrived.

Entertainment Weekly recently compiled a list of well-designed book covers from the past 25 years. Not fantastic but a solid list worth browsing.

The internet and other technologies have had differing impacts on the music and publishing businesses.

One of my friends proposed a theory I find compelling: Our cultural consumption exists on a spectrum from “individual” to “collective”. Technology has shifted the balance for both books and music. Digital distrbitution and the iPod have made music consumption much more individualistic, while the internet and global branding have made book consumption increasingly collective.

(via short schrift)

Books summed up in 3 lines or less.

The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe

C.S. LEWIS: Finally, a utopia ruled by children and populated by talking animals.

THE WITCH: Hi, I’m a sexually mature woman of power and confidence.

C.S. LEWIS: Ah! Kill it, lion Jesus!

Michael Lewis, author of Moneyball, The Blind Side, etc, has moved back to his native New Orleans to work on a book “that will center on the restoration of New Orleans”. Back in Aug 2007, Lewis wrote an article for the NY Times Magazine about Hurricane Katrina and the economics of catastrophe. (thx, brian)

While we’re on the topic of The Curious Case of Benjamin Button, Andrew Sean Greer wrote a book with a similar premise published in 2004 called The Confessions of Max Tivoli. It was based in part on the same Fitzgerald story as Fincher’s film.

Mr. Greer is candid about the precedents: F. Scott Fitzgerald told a related story in “The Curious Case of Benjamin Button,” and that in turn was inspired by a remark of Mark Twain that the best part of life came at the beginning and the worst part at the end. Later Fitzgerald found “an almost identical plot” in Samuel Butler’s “Note-books.” In “The Sword and the Stone,” which Mr. Greer read as a child, Merlin ages backward. Mr. Greer carries it further back, to Greek mythology, and forward to “Mork & Mindy,” in which Jonathan Winters played a baby. And at one book signing, he said, a reader asked him if he knew about the “Star Trek” episode in which ——

Actually, when he began the book he was thinking more of Bob Dylan. In 2001, having published a collection of stories and in the middle of writing a novel, he found himself singing “My Back Pages” — “I was so much older then, I’m younger than that now” — and he had what amounted to an epiphany. “I thought that could be a book not like anything I’d written before,” he said. “It sounded like a wild adventure that no one’s going to want to read, but it could be a lot of fun, and maybe that’s the point of it.”

This passage from a NY Times review of Tivoli provides a good sense of what the tone of the film might be:

For when the repercussions of Max’s reverse aging are eventually understood, the tragedy of his predicament becomes clear. Not only does he have the exact year of his death forever staring him in the face (1941, when he will complete his 70-year process of anti-decay), but he must also live his entire life, except for a few brief months in 1906 when his real and apparent ages coincide, being something other than what he seems.

Oh, and Shaun Inman quotes from Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse-Five about WWII moving backwards:

When the bombers got back to their base, the steel cylinders were taken from the racks and shipped back to the United States of America, where factories were operating day and night, dismantling the cylinders, separating the dangerous contents into minerals. Touchingly, it was mainly women who did this work. The minerals were then shipped to specialists in remote areas. It was their business to put them into the ground, to hide them cleverly, so they would never hurt anybody again.

(thx, jamaica)

2600, the hacker’s quarterly magazine, is publishing a best-of book compiling their most interesting and controversial articles.

Since its introduction in January of 1984, 2600 has been a unique source of information for readers with a strong sense of curiosity and an affinity for technology. The articles in 2600 have been consistently fascinating and frequently controversial. Over the past couple of decades the magazine has evolved from three sheets of loose-leaf paper stuffed into an envelope (readers “subscribed” by responding to a notice on a popular BBS frequented by hackers and sending in a SASE) to a professionally produced quarterly magazine. At the same time, the creators’ anticipated audience of “a few dozen people tied together in a closely knit circle of conspiracy and mischief” grew to a global audience of tens of thousands of subscribers.

Only 888 pages. (via bb)

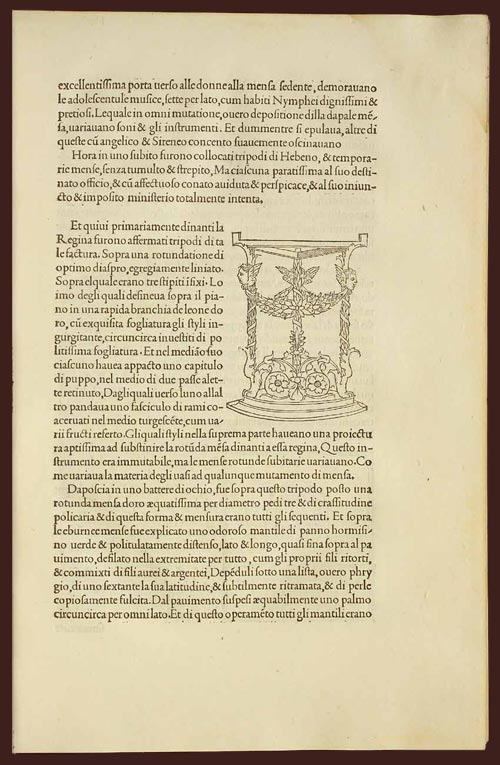

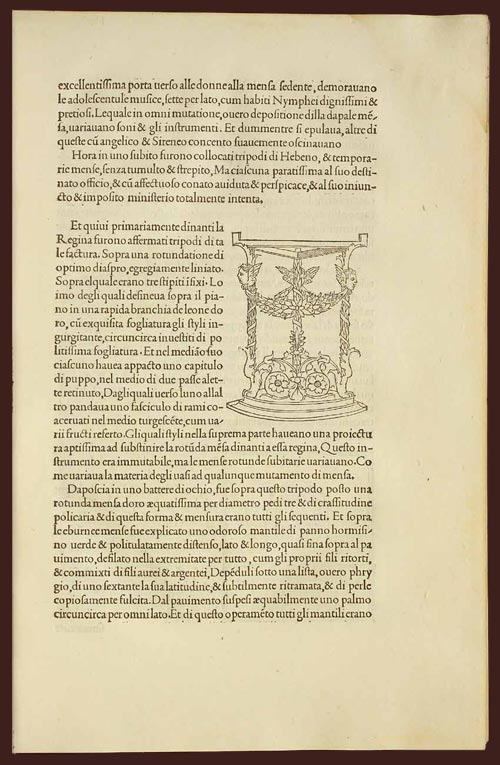

This is a page from a book called Hypnerotomachia Poliphili.

Any guesses as to when it was published? The title, Latin text, yellowed paper, and lack of page numbers might tip you off that it wasn’t exactly released yesterday. Turns out that Hypnerotomachia Poliphili was published in 1499, more than 500 years ago and only 44 years after Gutenberg published his famous Bible. It belongs to a group of books collectively referred to as incunabula, books printed with a printing press using movable type before 1501.

To contemporary eyes, the HP looks almost modern. The text is very readable. The typography, layout, and the way the text flows around the illustration; none of it looks out of the ordinary. When compared to other books of the time (e.g. take a look at a page from the Gutenberg Bible), its modernity is downright eerie. The most obvious difference is the absence of the blackletter typeface. Blackletter was a popular choice because it resembled closely the handwritten script that preceded the printing press, and I imagine its use smoothed the transition to books printed by press. HP dispensed with blackletter and instead used what came to be known as Bembo, a humanist typeface based on the handwriting of Renaissance-era Italian scholars. From a MIT Press e-book on the HP:

One of the features of the Hypnerotomachia that has attracted the attention of scholars has been its use of the famed Aldine “Roman” type font, invented by Nicholas Jenson but distilled into an abstract ideal by Francesco Biffi da Bologna, a jeweler who became Aldus’s celebrated cutter. This font — generally viewed as originating in the efforts of the humanist lovers of belles-lettres and renowned calligraphers such as Petrarch, Poggio Bracciolini, Niccolo Niccoli, Felice Feliciano, Leon Battista Alberti, and Luca Pacioli, to re-create the script of classical antiquity — appeared for the first time in Bembo’s De Aetna. Recut, it appeared in its second and perfected version in the Hypnerotomachia.

In that way, Hypnerotomachia Poliphili is both a throwback to Roman times and an indication of things to come.

The MIT Press site also notes a number of other significant aspects of the book. As seen above, illustrations are integrated into the main text, allowing “the eye to slip back and forth from textual description and corresponding visual representation with the greatest of ease”. In his 2006 book, Beautiful Evidence, Edward Tufte says:

Overall, the design of Hypnerotomachia tightly integrates the relevant text with the relevant image, a cognitive integration along with the celebrated optical integration.

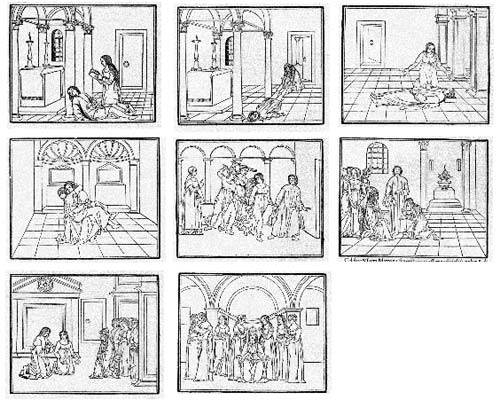

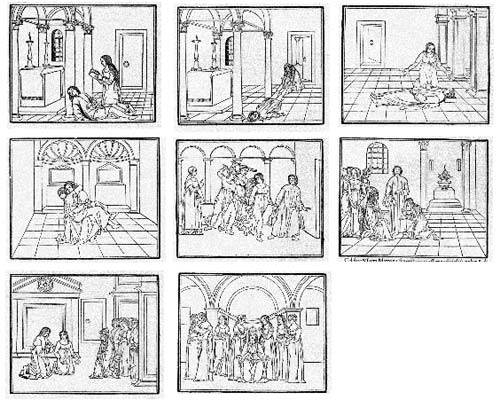

Several pages in the book make use of the text itself to illustrate the shapes of wine goblets. The HP also contained aspects of film, comics, and storyboarding…successive illustrations advanced action begun on previous pages:

All of which makes the following puzzling:

The Hypnerotomachia Poliphili is one of the most unreadable books ever published. The first inkling of difficulty occurs at the moment one picks up the book and tries to utter its tongue-twisting, practically unpronounceable title. The difficulty only heightens as one flips through the pages and tries to decipher the strange, baffling, inscrutable prose, replete with recondite references, teeming with tortuous terminology, choked with pulsating, prolix, plethoric passages. Now in Tuscan, now in Latin, now in Greek — elsewhere in Hebrew, Arabic, Chaldean and hieroglyphs — the author has created a pandemonium of unruly sentences that demand the unrelenting skills of a prodigiously endowed polyglot in order to be understood.

It’s fascinating that a book so readable, so beautifully printed, and so modern would also be so difficult to read. If you’d like to take a crack at it, scans of the entire book are available here and here. The English translation is available on Amazon.

Robert McCrum, the outgoing literary editor of The Observer, recently summed up the last decade in books in ten short chapters (with accompanying timeline).

People will argue about the decisive milestones (I have come up with my own 10, which I have set out in chapters), but there will be general agreement that, in Britain, a decade of change starts with the election of New Labour in 1997. That was also the year Random House launched its website, John Updike published a short story online and Vintage started a series of reading guides to encourage new book clubs. As well as new readers, the millennium saw the emergence of a new literary generation, writers born in the Sixties and Seventies, and few of them more fascinating than Zadie Smith…

McCrum also shares a tidbit about Malcolm Gladwell’s first book which I’d never heard before.

The Tipping Point was almost a flop. It was published to mixed reviews in the US, did no serious business in the UK and was saved by — yes — word of mouth. After a dismal launch, and as a desperate last resort, Gladwell persuaded his American publisher to sponsor a US-wide lecture tour. Only then did the book ‘tip’. Eventually, it would become a literary success of its time, turn its author into a pop cultural guru and spend seven years on the New York Times bestseller list. This was one of those pivotal moments that illustrates the story of this decade.

At the WH Smith shop at Heathrow last weekend, the paperback copy of The Tipping Point was still #5 on the business bestsellers list and nearly sold out.

On the occasion of the release of his 2000 Rolling Stone essay on John McCain’s 2000 presidential campaign in unabridged and expanded book form, David Foster Wallace gives a short interview to the WSJ.

McCain himself has obviously changed [since the 2000 campaign]; his flipperoos and weaselings on Roe v. Wade, campaign finance, the toxicity of lobbyists, Iraq timetables, etc. are just some of what make him a less interesting, more depressing political figure now — for me, at least. It’s all understandable, of course — he’s the GOP nominee now, not an insurgent maverick. Understandable, but depressing. As part of the essay talks about, there’s an enormous difference between running an insurgent Hail-Mary-type longshot campaign and being a viable candidate (it was right around New Hampshire in 2000 that McCain began to change from the former to the latter), and there are some deep, really rather troubling questions about whether serious honor and candor and principle remain possible for someone who wants to really maybe win.

(thx, bill)

At the very moment that humans discovered the scale of the universe and found that their most unconstrained fancies were in fact dwarfed by the true dimensions of even the Milky Way Galaxy, they took steps that ensured that their descendants would be unable to see the stars at all. For a million years humans had grown up with a personal daily knowledge of the vault of heaven. In the last few thousand years they began building and emigrating to the cities. In the last few decades, a major fraction of the human population had abandoned a rustic way of life. As technology developed and the cities were polluted, the nights became starless. New generations grew to maturity wholly ignorant of the sky that had transfixed their ancestors and had stimulated the modern age of science and technology. Without even noticing, just as astronomy entered a golden age most people cut themselves off from the sky, a cosmic isolationism that only ended with the dawn of space exploration.

That’s Carl Sagan in Contact from 1985. The effects of light pollution were documented in the New Yorker last August.

Another new book out in the fall is Thomas Keller’s Under Pressure, the chef’s long-awaited cookbook on sous vide cooking.

In “Under Pressure”, Thomas Keller shows us how sous vide, which involves packing food in airtight plastic bags and cooking at low heat, achieves results that other cooking methods simply cannot — in flavor and precision. For example, steak that is a perfect medium rare from top to bottom; and meltingly tender yet medium rare short ribs that haven’t lost their flavor to the sauce. Fish, which has a small window of doneness, is easier to finesse, and salmon develops a voluptuous texture when cooked at a low temperature. Fruit and vegetables benefit too, retaining their bright colors while achieving remarkable textures. There is wonderment in cooking sous vide — in the ease and precision (salmon cooked at 123 degrees versus 120 degrees!) and the capacity to cook a piece of meat (or glaze carrots, or poach lobster) uniformly.

Under Pressure is out October 1, 2008 and plays Bowie when you open the cover. Keller and Michael Ruhlman have also begun work on a book that “will focus on family-style cooking, in the style of Ad Hoc, and great food to cook at home”.

The Amazon page for Malcolm Gladwell’s new book is up. From here, we learn that the full title is “Outliers: Why Some People Succeed and Some Don’t” and what the cover looks like. Here’s the description:

In this stunning new book, Malcolm Gladwell takes us on an intellectual journey through the world of “outliers” — the best and the brightest, the most famous and the most successful. He asks the question: what makes high-achievers different? His answer is that we pay too much attention to what successful people are like, and too little attention to where they are from: that is, their culture, their family, their generation, and the idiosyncratic experiences of their upbringing. Along the way he explains the secrets of software billionaires, what it takes to be a great soccer player, why Asians are good at math, and what made the Beatles the greatest rock band.

And an excerpt from the Little, Brown catalog:

Outliers is a book about success. It starts with a very simple question: what is the difference between those who do something special with their lives and everyone else? In Outliers, we’re going to visit a genius who lives on a horse farm in Northern Missouri. We’re going to examine the bizarre histories of professional hockey and soccer players, and look into the peculiar childhood of Bill Gates, and spend time in a Chinese rice paddy, and investigate the world’s greatest law firm, and wonder about what distinguishes pilots who crash planes from those who don’t. And in examining the lives of the remarkable among us — the brilliant, the exceptional and the unusual — I want to convince you that the way we think about success is all wrong.

This doesn’t sound exactly what I had heard his new book was going to be.

A few days ago, New Yorker writer Malcolm Gladwell noted that he’s almost finished with his third book. I’ve learned that the subject of this book is the future of the workplace with subtopics of education and genius.

I guess if you flip those around, that describes Outliers marginally well. According to Amazon, the book is due on November 18, 2008. (thx, kyösti)

I just recently picked up on the visual pun on the cover of Cal Henderson’s Building Scalable Web Sites.

A list of 1001 (fiction) Books That You Must Read Before You Die, from a book of the same name. I read too much nonfiction to be well-read fiction-wise, but I have read these thirty from the list:

The Corrections, Jonathan Franzen

House of Leaves, Mark Z. Danielewski

Infinite Jest, David Foster Wallace*

The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle, Haruki Murakami*

Contact, Carl Sagan*

The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, Douglas Adams

One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn

The Lord of the Rings, J.R.R. Tolkien*

Lolita, Vladimir Nabokov*

The Old Man and the Sea, Ernest Hemingway

The Catcher in the Rye, J.D. Salinger

Nineteen Eighty-Four, George Orwell*

Cry, the Beloved Country, Alan Paton

Animal Farm, George Orwell

The Little Prince, Antoine de Saint-Exupéry

The Hobbit, J.R.R. Tolkien*

Brave New World, Aldous Huxley

The Great Gatsby, F. Scott Fitzgerald

The Time Machine, H.G. Wells

The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes, Arthur Conan Doyle

The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Mark Twain

Around the World in Eighty Days, Jules Verne

Little Women, Louisa May Alcott

Crime and Punishment, Fyodor Dostoevsky

Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, Lewis Carroll

A Christmas Carol, Charles Dickens

Pride and Prejudice, Jane Austen*

Candide, Voltaire

Gulliver’s Travels, Jonathan Swift

Robinson Crusoe, Daniel Defoe

Some of my very favorites are on there.

Update: Following Marco’s lead, I’ve marked some favorites with an asterisk. Under duress, I’d admit to the following as my top three favorite fiction books, in order: Infinite Jest, 1984, and Lolita.

This is the second rave review I’ve read of Perfumes: The Guide.

Now there’s a book called Perfumes: The Guide, by the husband and wife team of Luca Turin and Tania Sanchez, which is not just enlightening, but beautifully written, brilliant, often very funny, and occasionally profound. In fact, it’s as vivid as any criticism I’ve come across in the last few years, and what’s more a revelation: part history, part swoon, part plaint. All of the other reading I was supposed to do was put aside while I went through it, and it took me some time to finish, in part because I was savoring it and in part because I kept stopping to copy out passages to e-mail off to friends. In the library of books both useful and delightful, it deserves a place on the shelves somewhere between Pauline Kael’s 5001 Nights at the Movies and Brillat-Savarin’s incomparable Physiology of Taste.

The first review was this New Yorker article:

The joy of Turin and Sanchez’s book, however, is their ability to write about smell in a way that manages to combine the science of the subject with the vocabulary of scent in witty, vivid descriptions of what these smells are like. Their work is, quite simply, ravishingly entertaining, and it passes the high test that their praise is even more compelling than their criticism.

Perfume is one of those things that I don’t particularly like in real life but that I really enjoy reading about.

Newer posts

Older posts

Stay Connected