kottke.org posts about libraries

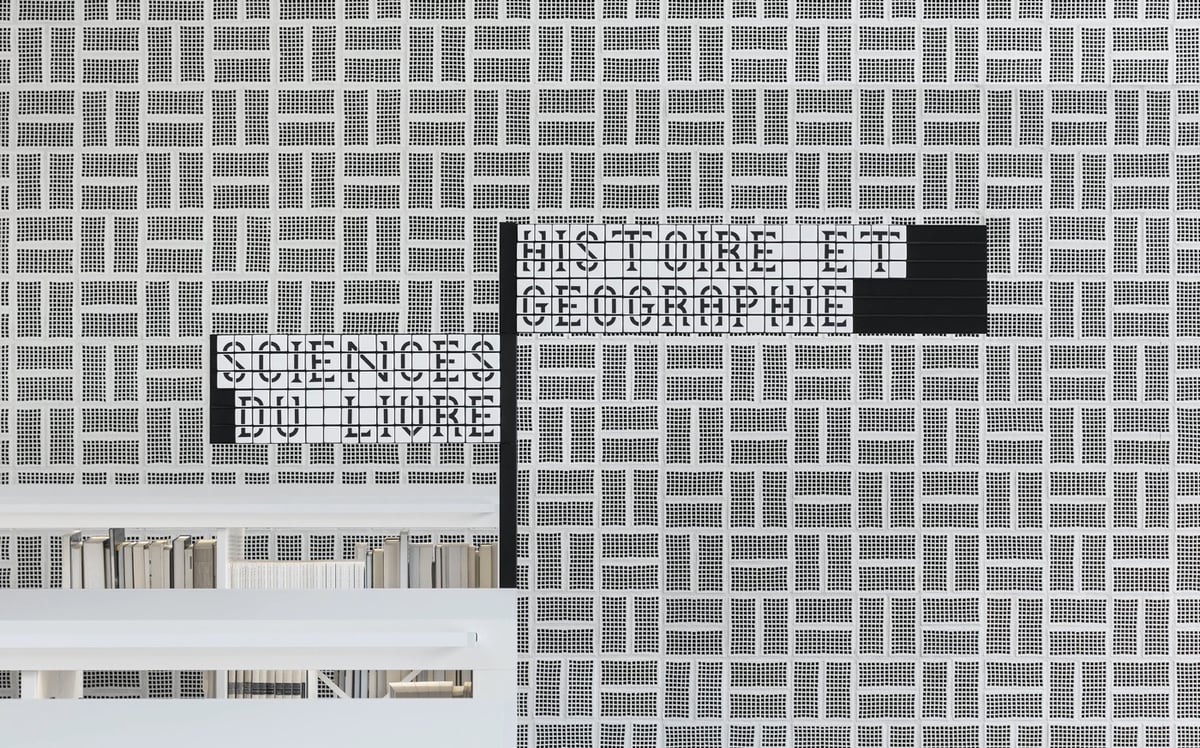

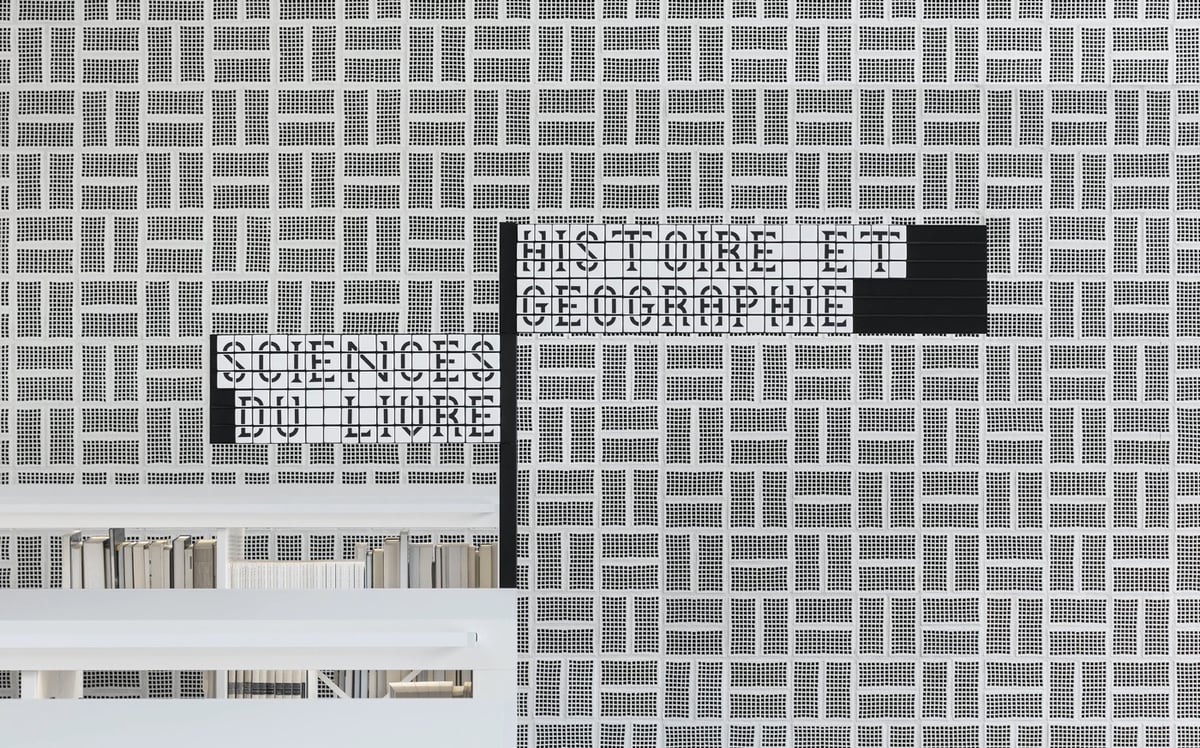

Sascha Lobe’s team at Pentagram has designed a functional and stylish modular signage system for the National Library of Luxembourg. The signs use cubes (inspired by LED clock displays?) that can be reconfigured into different words by library staff.

Numerical and alphabetical cubes are the foundation of the BnL’s modular signage system. In handling massive volumes of information and growing library collections, it is essential to free the library staff from rigid systems and equip them with the ability to easily make signage changes.

The flexible signage plan, consisting of 25,000 resin cubes, 6000 tableaus and 2,400 numerical shelving characters, enables staff to independently customize information as the library’s collection fluctuates. The resin cubes, constructed from a durable material, also translate the timelessness of the library and its long-standing presence throughout the years and into the future.

The only (but perhaps significant) downside to the signs is that they are not actually super legible when compared to a non-modular alternative. They sure do look great though.

Update: This post got shared on Twitter by a couple of librarian pals and Librarian Twitter was not impressed by this signage at all. Not legible, not accessible, and difficult/fiddly to maintain were the main complaints. As someone who believes that design is primarily about how something works and not how something looks, I’m a bit embarrassed that I didn’t hit that point harder in this post. I do love the aesthetics of the project, but from the photos, the legibility looks terrible. Maybe it’s different while navigating the space in person, but if not, you have to wonder how helpful hard-to-read signs are to patrons.

The Finns love libraries, and a new fabulous one opened last year in Helsinki. Tommi Laitio, Helsinki’s executive director for culture and leisure was at the CityLab DC conference recently and presented some of the thinking behind Finland’s investments in libraries and culture, and why they are so important to their country.

“This progress from one of the poorest countries of Europe to one of the most prosperous has not been an accident. It’s based on this idea that when there are so few of us—only 5.5 million people—everyone has to live up to their full potential,” he said. “Our society is fundamentally dependent on people being able to trust the kindness of strangers.”

One of the goals of the Oodi library is to make them less afraid of the various contemporary anxieties and from more informed citizens.

Nordic-style social services have not shielded the residents of Finland’s largest city from 21st-century anxieties about climate change, migrants, disruptive technology, and the other forces fueling right-leaning populist movements across Europe. Oodi, which was the product of a 10-year-long public consultation and design process, was conceived in part to resist these fears. “When people are afraid, they focus on short-term selfish solutions,” Laitio said. “They also start looking for scapegoats.”

The central library is built to serve as a kind of citizenship factory, a space for old and new residents to learn about the world, the city, and each other. It’s pointedly sited across from (and at the same level as) the Finnish Parliament House that it shares a public square with.

The library is widely popular and committed to openness.

Oodi just hit 3 million visitors this year—”a lot for a city of 650,000,” Laitio said. In its very first month, 420,000 Helsinki residents—almost two-thirds of the population—went to the library. Some may only have been skateboarders coming in to use the bathroom, but that’s fine: The library has a “commitment to openness and welcoming without judgement,” he said. “It’s probably the most diverse place in our city, in many ways.” (Emphasis mine)

The images are taken from this post on ArchDaily where you can also find a lot more views of the gorgeous spaces.

I superficially resemble Chuck Klosterman — we’re redheaded dudes with glasses and beards — but wouldn’t call myself a fan. I’ve enjoyed his writing from time to time as it’s popped up from here to there, but I’ve never read any of his books, nor am I particularly pressed to. It’s okay. He’s doing fine.

What I am struck by in this interview is the criteria Klosterman poses for liking writers and choosing their books. There’s two parts to it. Here it goes.

Which writers — novelists, playwrights, critics, journalists, poets — working today do you admire most?

This is an odd answer, but when I think about writers I “admire,” it has almost nothing to do with their books. It has more to do with how they manage their life. Writing seems to attract a lot of psychologically unhinged people, so I’m always impressed with authors who are able to view their career accurately, who are able to reconcile the inherent dissonance between commercial and critical success, and who seem to enjoy the process of writing without cannibalizing every other aspect of their existence in order to get it done. Jonathan Lethem seems like this kind of guy. George Saunders. Maria Semple. It’s possible, of course, that these writers aren’t the way they appear on the surface, and maybe if I knew them intimately I’d conclude they were all crazy. But then again, not seeming like a self-absorbed sociopath is 75 percent of the way to actually being a normal person.

Whose opinion on books do you most trust?

Part-time bookstore employees and research librarians. They have no agenda and plenty of free time. The research librarians are especially good, because they don’t even care if their suggestions make them seem cool.

1) What’s weird is we spent the better part of the twentieth century enshrining genius sociopaths at the top of the author pile. Some of this was necessary pushback against 19th century criticism that tended to be overly moralizing, equating the goodness of an author with the naively perceived goodness of their personal lives. But I wonder now whether we’re swinging back to that, by way of politics an everything else. Good writers should first and foremost be good people. Or at least, in Klosterman’s formulation, reasonably normal people.

2) This might be the most interesting piece of it for me. Librarians and bookstore employees. It makes a good deal of sense; they are the people who are closest to the books. But it also makes me wonder: whose opinion do you trust most when it comes to books? Friends? Critics? Publishers? Academics? Who’s got your number?

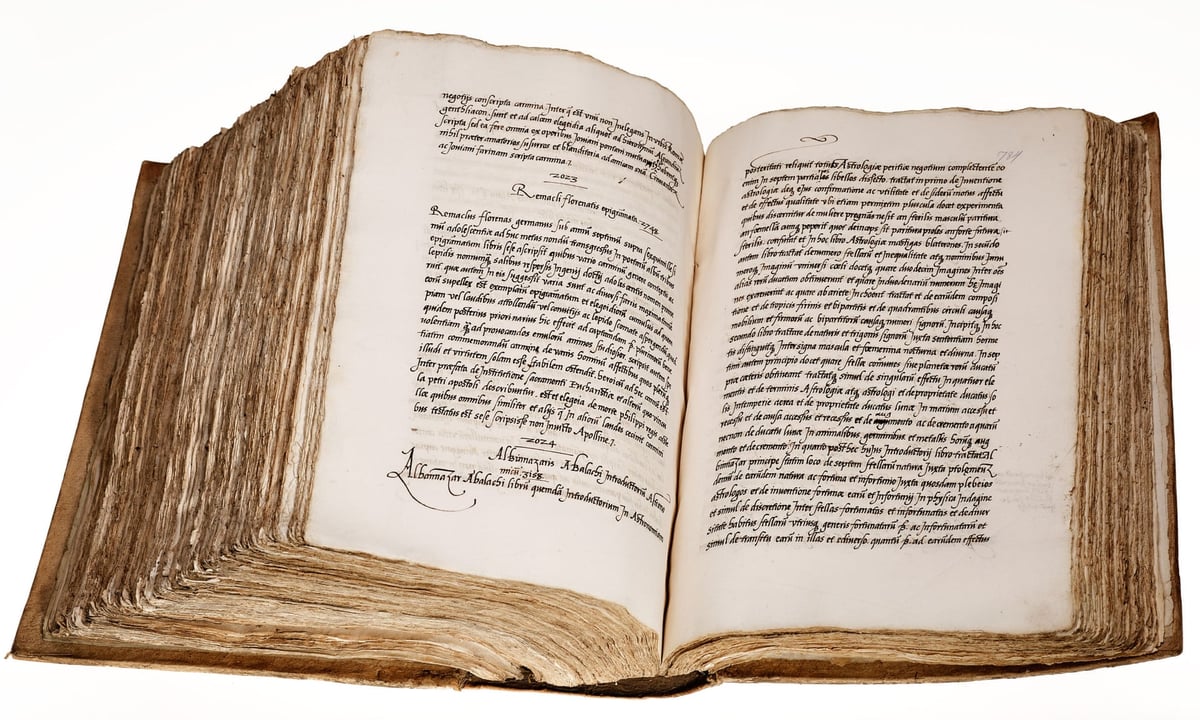

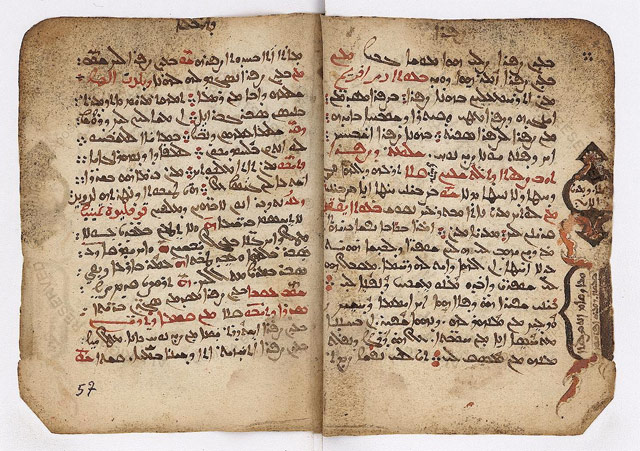

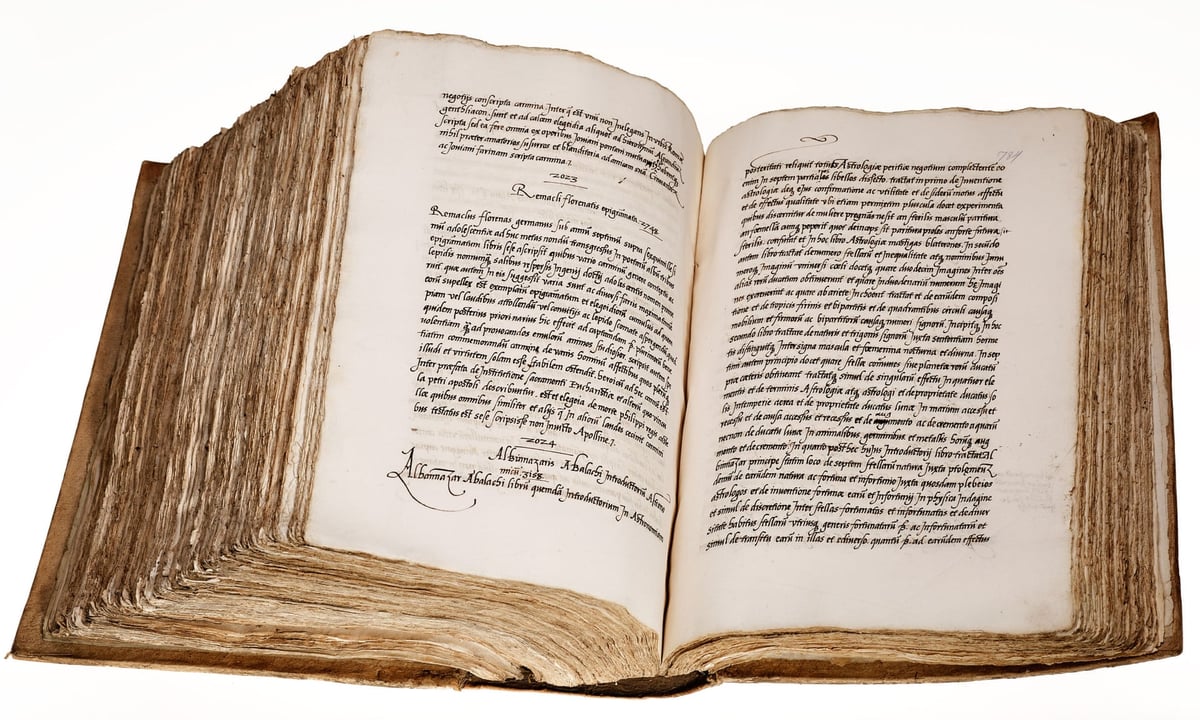

Hernando Colón was the illegitimate son of Christopher Columbus. He was also one of the great book collectors of 16th century Europe, having traveled extensively and assembled a library of about 15,000 volumes.

What’s left of Colón’s library has been housed in Seville Cathedral since 1552. The other evidence of the library is a catalogue, with epitomes and summaries of the books in the collection. But the catalog itself, called the Libro de los Epítomes, was thought to be lost, until it was identified in an unlikely collection belonging to “Árni Magnússon, an Icelandic scholar born in 1663, who donated his books to the University of Copenhagen on his death in 1730.”

The discovery in the Arnamagnæan Collection in Copenhagen is “extraordinary”, and a window into a “lost world of 16th-century books”, said Cambridge academic Dr Edward Wilson-Lee, author of the recent biography of Colón, The Catalogue of Shipwrecked Books.

“It’s a discovery of immense importance, not only because it contains so much information about how people read 500 years ago, but also, because it contains summaries of books that no longer exist, lost in every other form than these summaries,” said Wilson-Lee. “The idea that this object which was so central to this extraordinary early 16th-century project and which one always thought of with this great sense of loss, of what could have been if this had been preserved, for it then to just show up in Copenhagen perfectly preserved, at least 350 years after its last mention in Spain …”

Another choice quote from Wilson-Lee:

After amassing his collection, Colón employed a team of writers to read every book in the library and distill each into a little summary in Libro de los Epítomes, ranging from a couple of lines long for very short texts to about 30 pages for the complete works of Plato, which Wilson-Lee dubbed the “miracle of compression”.

Because Colón collected everything he could lay his hands on, the catalogue is a real record of what people were reading 500 years ago, rather than just the classics. “The important part of Hernando’s library is it’s not just Plato and Cortez, he’s summarising everything from almanacs to news pamphlets. This is really giving us a window into the entirety of early print, much of which has gone missing, and how people read it - a world that is largely lost to us,” said Wilson-Lee.

What a wonder.

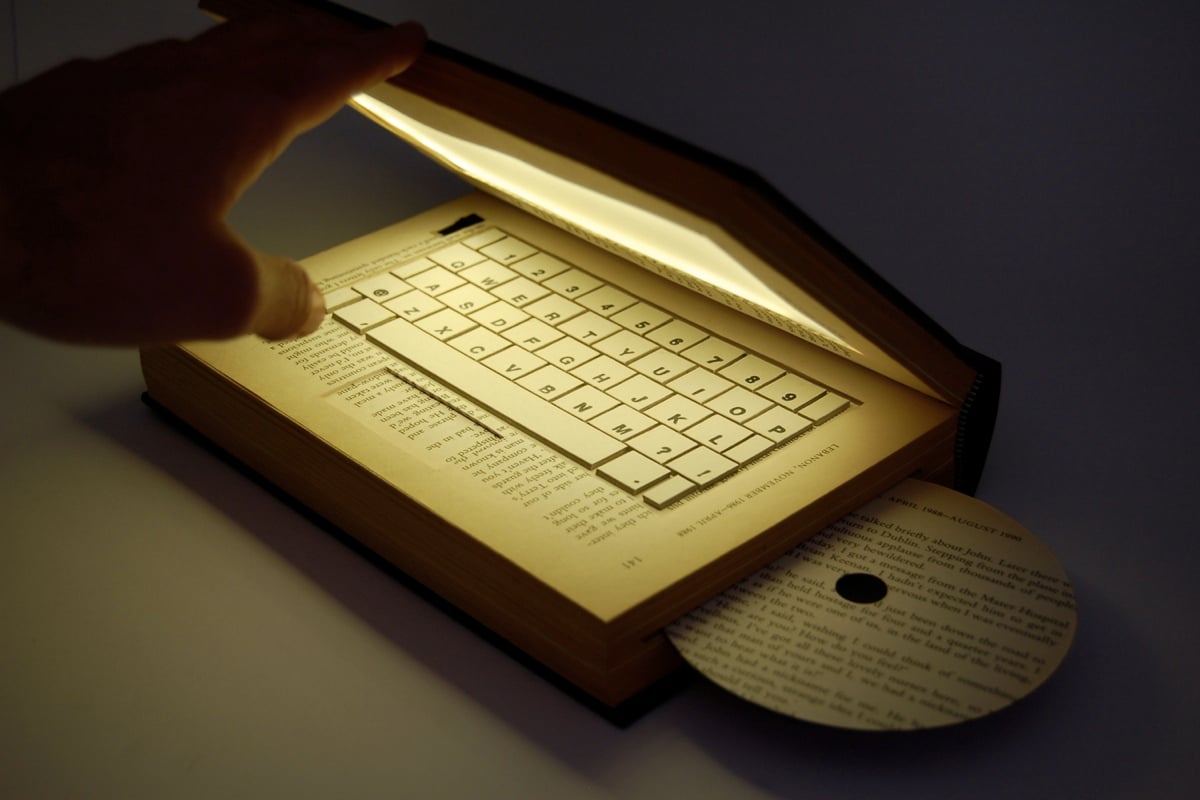

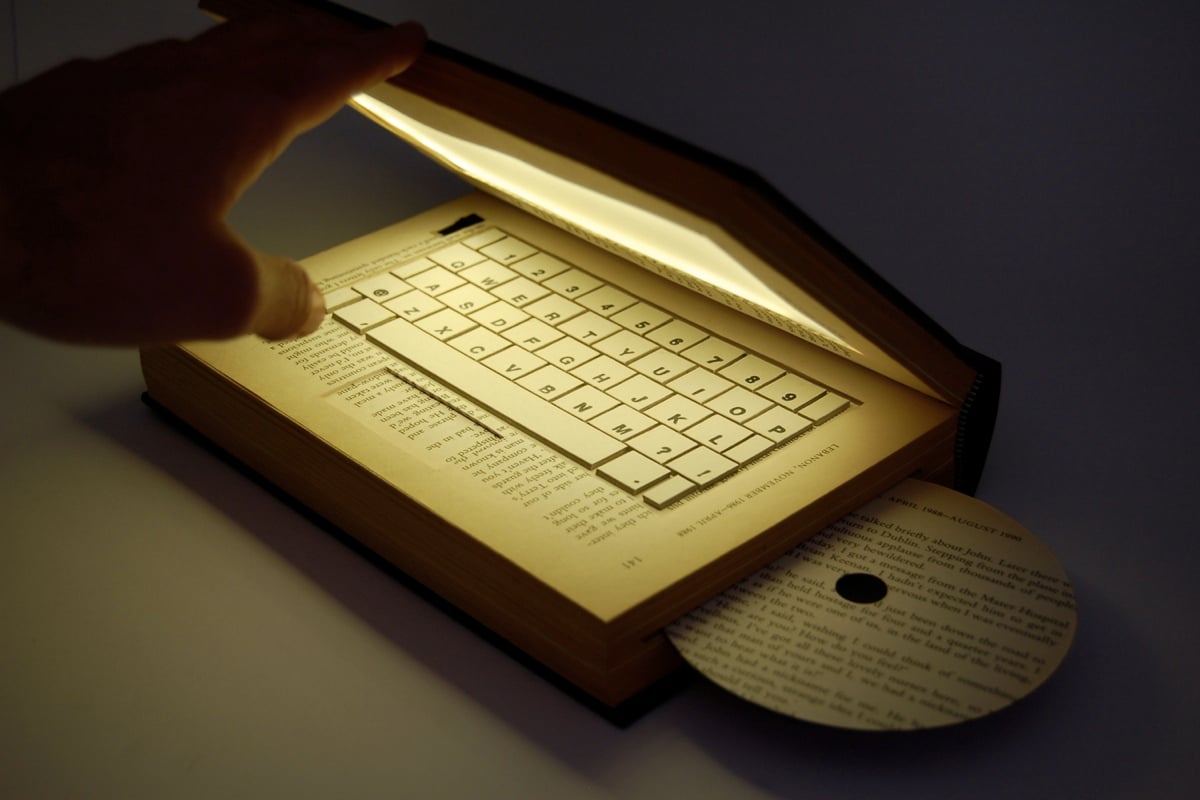

Writing in Wired, Craig Mod expertly dissects both the e-book revolution that never happened and the quieter one that actually did:

The Future Book was meant to be interactive, moving, alive. Its pages were supposed to be lush with whirling doodads, responsive, hands-on. The old paperback Zork choose-your-own-adventures were just the start. The Future Book would change depending on where you were, how you were feeling. It would incorporate your very environment into its story—the name of the coffee shop you were sitting at, your best friend’s birthday. It would be sly, maybe a little creepy. Definitely programmable. Ulysses would extend indefinitely in any direction you wanted to explore; just tap and some unique, mega-mind-blowing sui generis path of Joycean machine-learned words would wend itself out before your very eyes.

Prognostications about how technology would affect the form of paper books have been with us for centuries. Each new medium was poised to deform or murder the book: newspapers, photography, radio, movies, television, videogames, the internet.

That isn’t what happened. The book was neither murdered nor fundamentally transformed in its appearance, its networked quality, or its multimedia status. But the people and technologies around the book all did fundamentally change, and arguably, changed for the better.

Our Future Book is composed of email, tweets, YouTube videos, mailing lists, crowdfunding campaigns, PDF to .mobi converters, Amazon warehouses, and a surge of hyper-affordable offset printers in places like Hong Kong.

For a “book” is just the endpoint of a latticework of complex infrastructure, made increasingly accessible. Even if the endpoint stays stubbornly the same—either as an unchanging Kindle edition or simple paperback—the universe that produces, breathes life into, and supports books is changing in positive, inclusive ways, year by year. The Future Book is here and continues to evolve. You’re holding it. It’s exciting. It’s boring. It’s more important than it has ever been.

This is all clever, sharply observed, and best of all, true. But Craig is a very smart man, so I want to push him a little bit.

What he’s describing is the present book. The present book is an instantiation of the future book, in St. Augustine’s sense of the interconnectedness and unreality of the past, future, and eternity in the ephemerality of the present, sure. But what motivated discussions of the future book throughout the 20th and in the early 21st century was the animating force of the idea that the book had a future that was different from the present, whose seeds we could locate in the present but whose tree was yet to flourish. Craig Mod gives us a mature forest and says, “behold, the future.” But the present state of the book and discussions around the book feel as if that future has been foreclosed on; that all the moves that were left to be made have already been made, with Amazon the dominant inertial force locking the entire ecosystem into place.

But, in the entire history of the book, these moments of inertia have always been temporary. The ecosystem doesn’t remain locked in forever. So right now, Amazon, YouTube, and Kickstarter are the dominant players. Mailchimp being joined by Substack feels a little like Coke being joined by Pepsi; sure, it’s great to have the choice of a new generation, but the flavor is basically the same. So where is the next disruption going to come from?

I think the utopian moment for the future of the book ended not when Amazon routed its vendors and competitors, although the Obama DOJ deserves some blame in retrospect for handing them that win. I think it ended when the Google Books settlement died, leading to Google Books becoming, basically abandonware, when it was initially supposed to be the true Library of Babel. I think that project, the digitization of all printed matter, available for full-text search and full-image browsing on any device, and possible conversion to audio formats and chopped up into newsletters, and whatever way you want to re-imagine these old and new books, remains the gold standard for the future of the book.

There are many people and institutions still working on making this approach reality. The Library of Congress’s new digital-first, user-focused mission statement is inspiring. The Internet Archive continues to do the Lord’s work in digitizing and making available our digital heritage. HathiTrust is still one of the best ideas I’ve ever heard. The retrenchment of the Digital Public Library of America is a huge blow. But the basic idea of linking together libraries and cultural institutions into an enormous network with the goal of making their collections available in common is an idea that will never die.

I think there’s a huge commercial future for the book, and for reading more broadly, rooted in the institutions of the present that Craig identifies: crowdfunding, self-publishing, Amazon as a portal, email newsletters, etc. etc. But the noncommercial future of the book is where all the messianic energy still remains. It’s still the greatest opportunity and the hardest problem we have before us. It’s the problem that our generation has to solve. And at the moment, we’re nowhere.

Wonderful writer Susan Orlean1 is out with a new book called The Library Book, which is specifically about a 1986 fire at the Los Angeles Public Library and more generally a love letter to libraries. The New Yorker recently published an excerpt.

Our visits were never long enough for me — the library was so bountiful. I loved wandering around the shelves, scanning the spines of the books until something happened to catch my eye. Those trips were dreamy, frictionless interludes that promised I would leave richer than I arrived. It wasn’t like going to a store with my mom, which guaranteed a tug-of-war between what I desired and what she was willing to buy me; in the library, I could have anything I wanted. On the way home, I loved having the books stacked on my lap, pressing me under their solid, warm weight, their Mylar covers sticking to my thighs. It was such a thrill leaving a place with things you hadn’t paid for; such a thrill anticipating the new books we would read.

Like Orlean and probably many of you readers, I loved the library when I was a kid. Browsing the shelves, I felt like any and all knowledge was literally at my fingertips. My sister and I would each check out a mess of books, read them all in like a day and a half, and then we’d switch and read each others’ — I have read at least the first dozen of The Baby-Sitters Club books and a lot of Nancy Drew as well as all of Judy Blume’s pre-1990 oeuvre. Our family didn’t have a lot of money growing up and Orlean is spot-on with how wonderful & transformative the infinite library felt compared to the fraught retail environment of forbidden Pac-Man notepads, Bazooka Joe gum, and baseball cards.

Eric Klinenberg recently wrote an opinion piece for the NY Times called To Restore Civil Society, Start With the Library.

Libraries are an example of what I call “social infrastructure”: the physical spaces and organizations that shape the way people interact. Libraries don’t just provide free access to books and other cultural materials, they also offer things like companionship for older adults, de facto child care for busy parents, language instruction for immigrants and welcoming public spaces for the poor, the homeless and young people.

I recently spent a year doing ethnographic research in libraries in New York City. Again and again, I was reminded how essential libraries are, not only for a neighborhood’s vitality but also for helping to address all manner of personal problems.

For older people, especially widows, widowers and those who live alone, libraries are places for culture and company, through book clubs, movie nights, sewing circles and classes in art, current events and computing. For many, the library is the main place they interact with people from other generations.

For children and teenagers, libraries help instill an ethic of responsibility, to themselves and to their neighbors, by teaching them what it means to borrow and take care of something public, and to return it so others can have it too. For new parents, grandparents and caretakers who feel overwhelmed when watching an infant or a toddler by themselves, libraries are a godsend.

Khoi Vinh, who until fairly recently had taken public libraries for granted, followed on with some additional thoughts.

Even more radically, your time at the library comes with absolutely no expectation that you buy anything. Or even that you even transact at all. And there’s certainly no implication that your data or your rights are being surrendered in return for the services you partake in.

This rare openness and neutrality imbues libraries with a distinct sense of community, of us, of everyone having come together to fund and build and participate in this collective sharing of knowledge and space. All of that seems exceedingly rare in this increasingly commercial, exposed world of ours. In a way it’s quite amazing that the concept continues to persist at all.

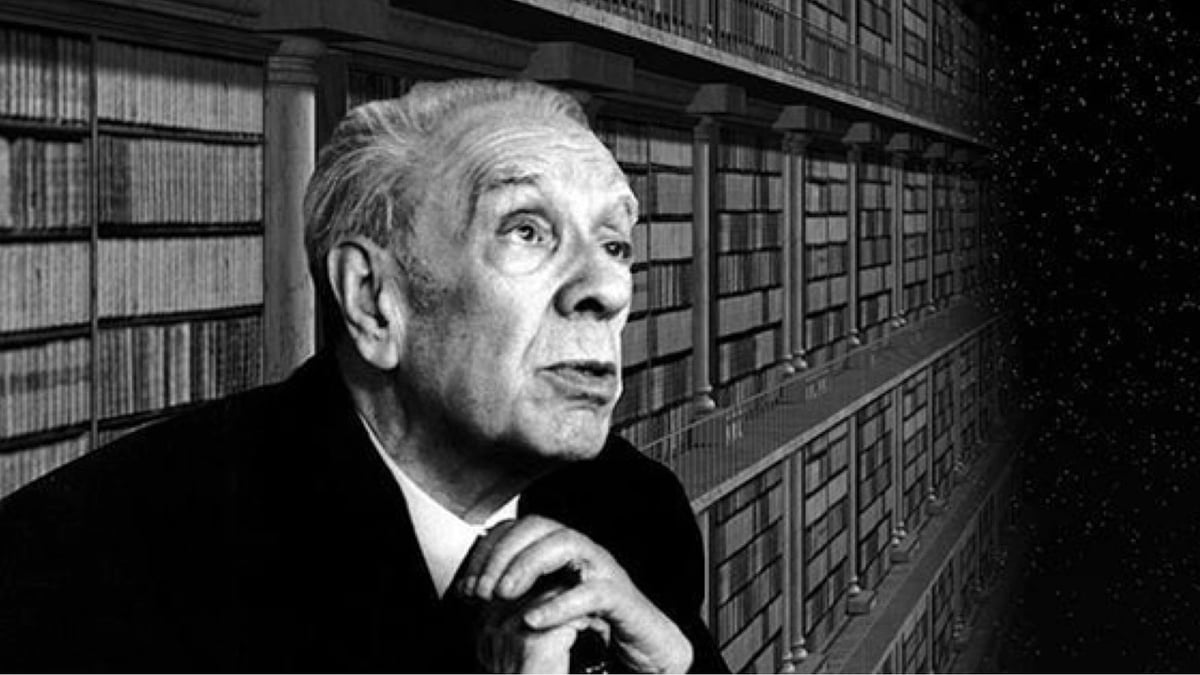

My favorite Jorge Luis Borges short story, “El Hacedor (The Maker),” is about the Greek poet Homer going blind:

He had never dwelled on memory’s delights. Impressions slid over him, vivid but ephemeral. A potter’s vermilion; the heavens laden with stars that were also gods; the moon, from which a lion had fallen; the slick feel of marble beneath slow sensitive fingertips; the taste of wild boar meat, eagerly torn by his white teeth; a Phoenician word; the black shadow a lance casts on yellow sand; the nearness of the sea or of a woman; a heavy wine, its roughness cut by honey-these could fill his soul completely. He knew what terror was, but he also knew anger and rage, and once he had been the first to scale an enemy wall. Eager, curious, casual, with no other law than fulfillment and the immediate indifference that ensues, he walked the varied earth and saw, on one seashore or another, the cities of men and their palaces. In crowded marketplaces or at the foot of a mountain whose uncertain peak might be inhabited by satyrs, he had listened to complicated tales which he accepted, as he accepted reality, without asking whether they were true or false.

Gradually now the beautiful universe was slipping away from him. A stubborn mist erased the outline of his hand, the night was no longer peopled by stars, the earth beneath his feet was unsure. Everything was growing distant and blurred. When he knew he was going blind he cried out; stoic modesty had not yet been invented and Hector could flee with impunity. I will not see again, he felt, either the sky filled with mythical dread, or this face that the years will transform. Over this desperation of his flesh passed days and nights. But one morning he awoke; he looked, no longer alarmed, at the dim things that surrounded him; and inexplicably he sensed, as one recognizes a tune or a voice, that now it was over and he had faced it, with fear but also with joy, hope, and curiosity. Then he descended into his memory, which seemed to him endless, and up from that vertigo he succeeded in bringing forth a forgotten recollection that shone like a coin under the rain, perhaps because he had never looked at it, unless in a dream.

Borges also gradually went blind, as had many members of his family. “The world of the blind is not the night that people imagine,” he said in a 1977 lecture called “Blindness,” collected in his magnificent posthumous anthology Selected Nonfictions. “I should say that I am speaking for myself, and for my father and my grandmother, who both died blind—blind, laughing, and brave, as I also hope to die. They inherited many things—blindness, for example—but one does not inherit courage.”

This lecture is the source of a famous Borges quote: “I had always imagined Paradise as a kind of library.” It does not usually include the context: Borges had been appointed as director of Argentina’s national library almost exactly when he became so blind he could no longer read.

No one should read self-pity or reproach

into this statement of the majesty of God;

who with such splendid irony

granted me books and blindness at one touch.

In his lecture, Borges discusses his own blindness, as well as that of Homer, Joyce, his predecessor at the library Paul Groussac, and a number of other writers. One of its most striking passages concerns John Milton, about whom Borges writes relatively little elsewhere. Milton, we’re told, went blind voluntarily, writing pamphlets in poor lighting to support the execution of Charles I, which landed him in political trouble after the Restoration. Borges likewise resisted, and survived Peron’s rule in Argentina.

Borges is especially struck by Milton’s Samson Agonistes, which is also about a blind hero who strikes down a wicked king.

He wanted to create a Greek tragedy. The action takes place in a single day, Samson’s last. Milton thought on the similarity of destinies, since he, like Samson, had been a strong man who was ultimately defeated. He was blind. And he wrote those verses which, according to Landor, he punctuated badly, but which in fact had to be “Eyeless, in Gaza, at the mill, with the slaves” — as if the misfortunes were accumulating on Samson.

Milton has a sonnet in which he speaks of his blindness. There is a line one can tell was written by a blind man. When he has to describe the world, he says, “In this dark world and wide.” It is precisely the world of the blind when they are alone, walking with hands outstretched, searching for props. Here we have an example — much more important than mine — of a man who overcomes blindness and does his work: Paradise Lost, Paradise Regained, Samson Agonistes, his best sonnets, part of A History of England, from the beginnings to the Norman Conquest. All of this was executed while he was blind; all of it had to be dictated to casual visitors.

Here we return to Borges’s “The Maker”:

Why did those memories come back to him, and why did they come without bitterness, as a mere foreshadowing of the present?

In grave amazement he understood. In this night too, in this night of his mortal eyes into this he was now descending, love and danger were again waiting. Ares and Aphrodite, for already he divined (already it encircled him) a murmur of glory and hexameters, a murmur of men defending a temple the gods will not save, and of black vessels searching the sea for a beloved isle, the murmur of the Odysseys and Iliads it was his destiny to sing and leave echoing concavely in the memory of man. These things we know, but not those that he felt when he descended into the last shade of all.

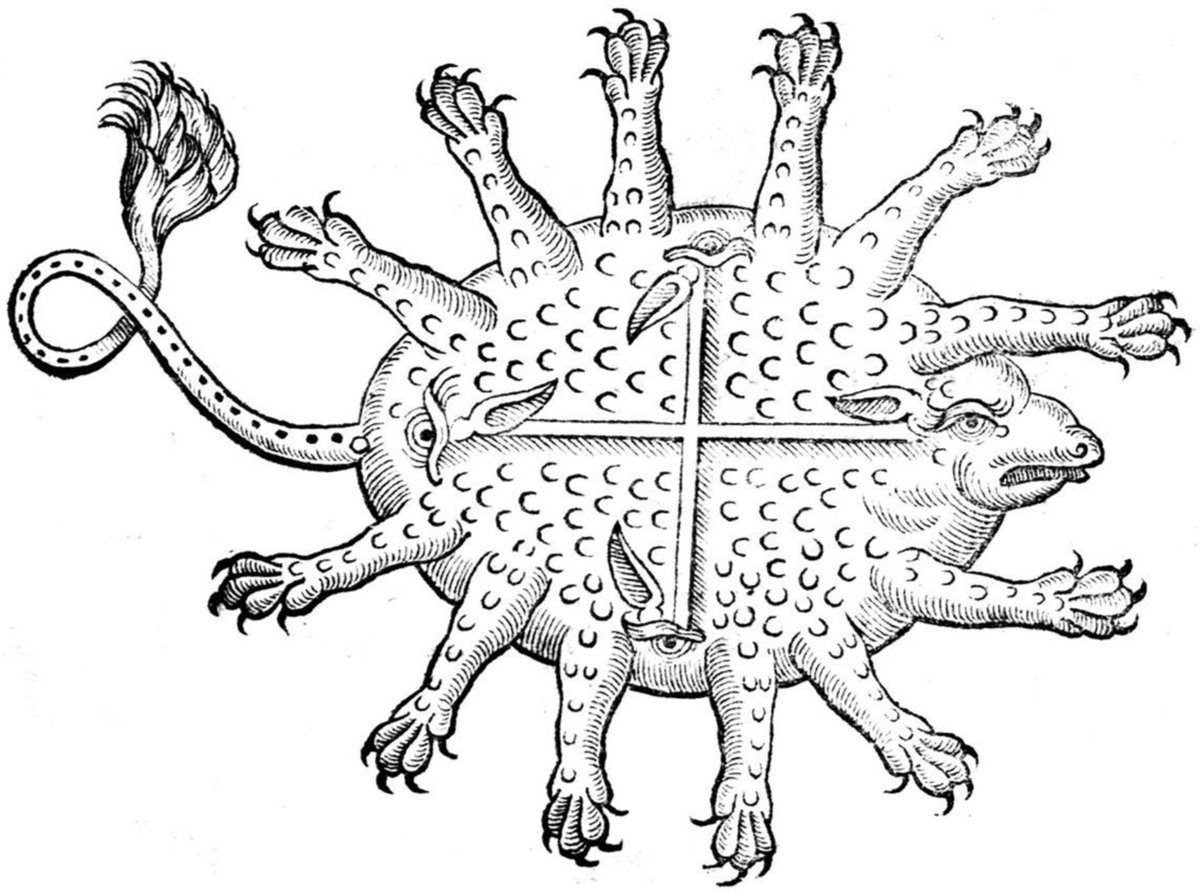

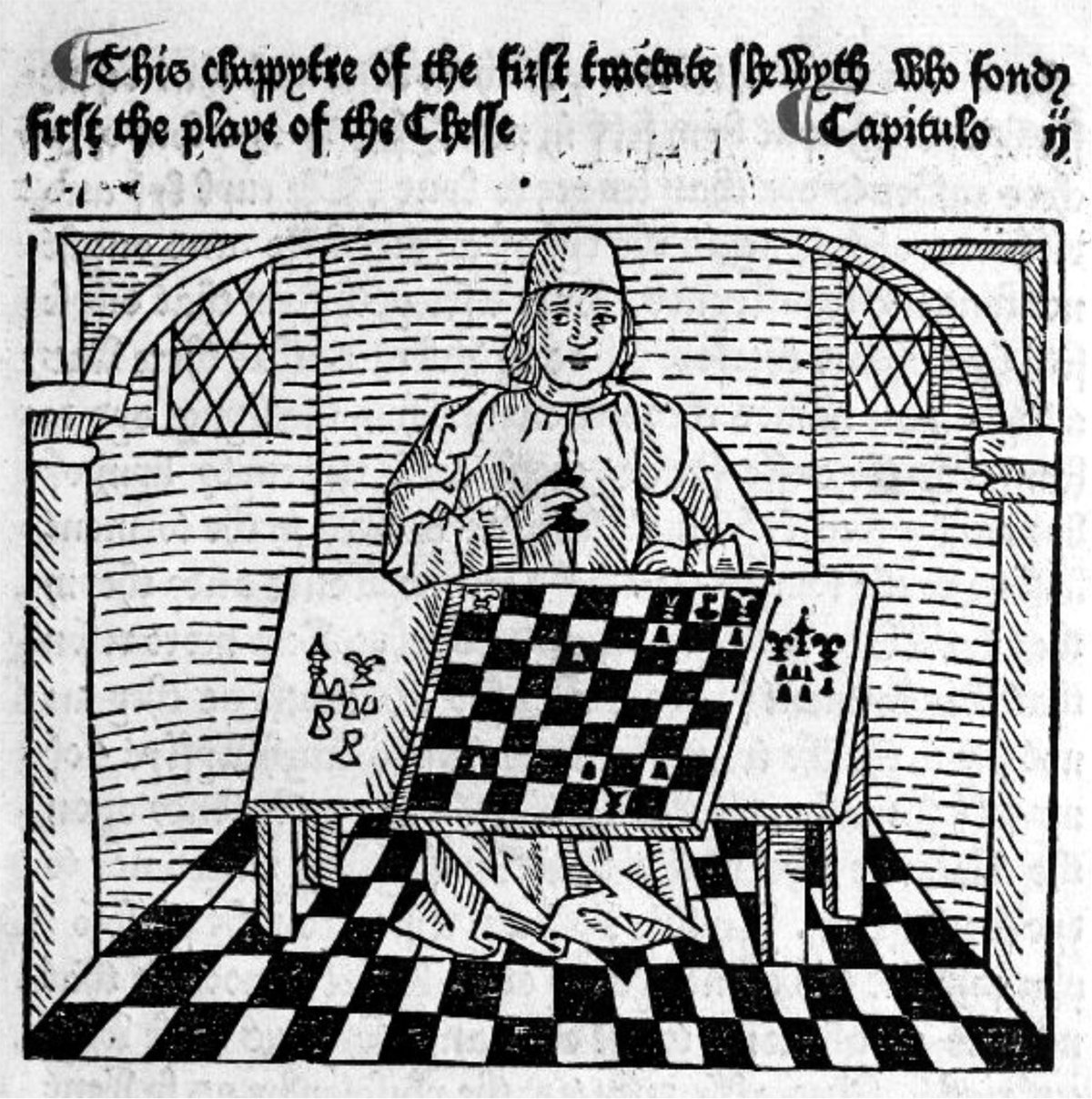

A bunch of libraries and museums have banded together for the Color Our Collections campaign, offering up free coloring books that let you color artworks from their collections. Participating institutions include the NYPL, the Biodiversity Heritage Library, the Smithsonian, the New York Botanical Garden, and the Bodleian Libraries at Oxford.

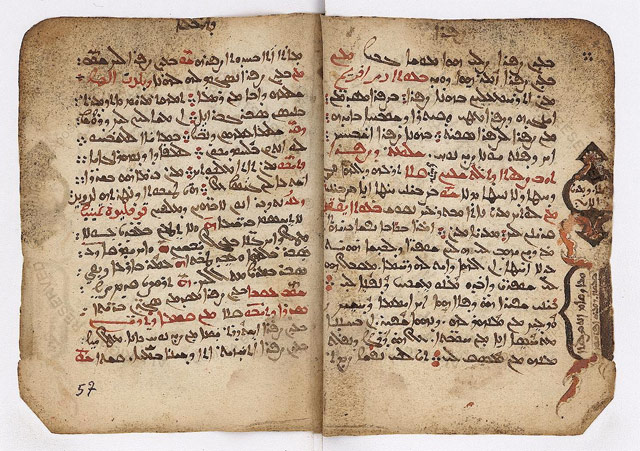

The Vatican is beginning the process of digitizing its extensive library of books and manuscripts, previously only available to a select few scholars and historians. Their plan calls for an initial 3000 manuscripts to be scanned, with the rest of the 82,000 other documents to hopefully follow.

That’s 41 million pages spanning nearly 2,000 years of church history that will soon be clickable, zoomable, and presumably, printable. When all is said and done, you’ll be able to read the Psalms handwritten across 13th-century vellum on your iPhone — so long as you speak ancient Greek.

Jay Walker made a lot of money and used some of it to finance a ridiculously huge and nerdy library in his house. Wired has a tour.

The massive “book” by the window is a specially commissioned, internally lit 2.5-ton Clyde Lynds sculpture. It’s meant to embody the spirit of the library: the mind on the right page, the universe on the left. Pointing out to that universe is a powerful Questar 7 telescope. On the rear of the table (from left) are a globe of the moon signed by nine of the 12 astronauts who walked on it, a rare 19th-century sky atlas with white stars against a black sky, and a fragment from the Sikhote-Alin meteorite that fell in Russia in 1947—it’s tiny but weighs 15 pounds. In the foreground is Andrea Cellarius’ hand-painted celestial atlas from 1660. “It has the first published maps where Earth was not the center of the solar system,” Walker says. “It divides the age of faith from the age of reason.”

(via design observer)

A thoughtful letter from a librarian to a woman who wanted a book depicting gay marriage removed from the children’s section of the library.

I fully appreciate that you, and some of your friends, strongly disagree with its viewpoint. But if the library is doing its job, there are lots of books in our collection that people won’t agree with; there are certainly many that I object to. Library collections don’t imply endorsement; they imply access to the many different ideas of our culture, which is precisely our purpose in public life.

SMU is pursuing the George W. Bush presidential library but the faculty says, in effect, “That crook? Hell no!”

Top 1000 publications owned by US libraries. The Holy Bible, the 2000 US Census, and Mother Goose top the list. (via o’r)

In addition to books, you can check people out of the Malmo, Sweden library. The library “will let curious visitors check out living people for a 45-minute chat in a project meant to tear down prejudices about different religions, nationalities, or professions”.

Stay Connected