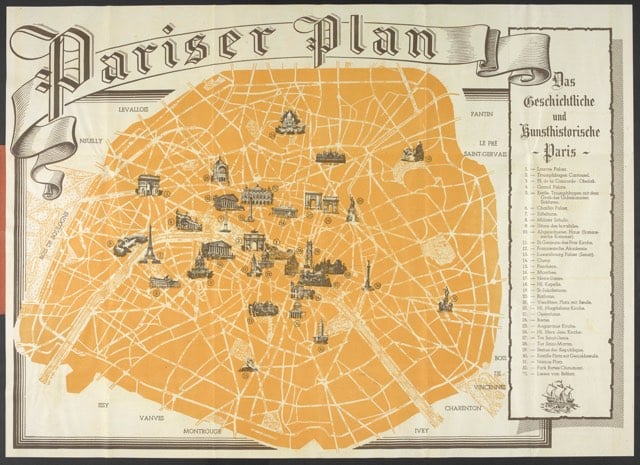

1940 Nazi tourist map of Paris

In 1940, Germany published a tourist map of occupied Paris intended for use by German soldiers on leave.

This site is made possible by member support. 💞

Big thanks to Arcustech for hosting the site and offering amazing tech support.

When you buy through links on kottke.org, I may earn an affiliate commission. Thanks for supporting the site!

kottke.org. home of fine hypertext products since 1998.

In 1940, Germany published a tourist map of occupied Paris intended for use by German soldiers on leave.

After the end of World War II in Europe, homosexual prisoners of liberated concentration camps were refused reparations and some were even thrown into jail without credit for their time served in the camps. From the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum:

After the war, homosexual concentration camp prisoners were not acknowledged as victims of Nazi persecution, and reparations were refused. Under the Allied Military Government of Germany, some homosexuals were forced to serve out their terms of imprisonment, regardless of the time spent in concentration camps. The 1935 version of Paragraph 175 remained in effect in the Federal Republic (West Germany) until 1969, so that well after liberation, homosexuals continued to fear arrest and incarceration.

After 1945, it was no longer a crime to be Jewish in Germany, but homosexuality was another matter. Paragraph 175 of the German Criminal Code had been on the books since 1871. An English translation of the earliest version read simply:

Unnatural fornication, whether between persons of the male sex or of humans with beasts, is to be punished by imprisonment; a sentence of loss of civil rights may also be passed.

In Germany, homosexuality was considered a crime worthy of up to five years of imprisonment until Paragraph 175 was voided in 1994.

Update: I missed this while writing the post: Paragraph 175 was amended in 1969 to limit enforcement to engaging in homosexual acts with minors (under 21 years). (thx, eric)

On a strong recommendation from Meg, I have been reading Peter Gray’s Free to Learn: Why Unleashing the Instinct to Play Will Make Our Children Happier, More Self-Reliant, and Better Students for Life. Gray is a developmental psychologist and in Free to Learn he argues that 1) children learn primarily through self-directed play (by themselves and with other children), and 2) our current teacher-driven educational system is stifling this instinct in our kids, big-time.

I have a lot to say about Free to Learn (it’s fascinating), but I wanted to share one of the most surprising and unsettling passages in the book. In a chapter on the role of play in social and emotional development, Gray discusses play that might be considered inappropriate, dangerous, or forbidden by adults: fighting, violent video games, climbing “too high”, etc. As part of the discussion, he shares some of what George Eisen uncovered while writing his book, Children and Play in the Holocaust.

In the ghettos, the first stage in concentration before prisoners were sent off to labor and extermination camps, parents tried desperately to divert their children’s attention from the horrors around them and to preserve some semblance of the innocent play the children had known before. They created makeshift playgrounds and tried to lead the children in traditional games. The adults themselves played in ways aimed at psychological escape from their grim situation, if they played at all. For example, one man traded a crust of bread for a chessboard, because by playing chess he could forget his hunger. But the children would have none of that. They played games designed to confront, not avoid, the horrors. They played games of war, of “blowing up bunkers,” of “slaughtering,” of “seizing the clothes of the dead,” and games of resistance. At Vilna, Jewish children played “Jews and Gestapomen,” in which the Jews would overpower their tormenters and beat them with their own rifles (sticks).

Even in the extermination camps, the children who were still healthy enough to move around played. In one camp they played a game called “tickling the corpse.” At Auschwitz-Birkenau they dared one another to touch the electric fence. They played “gas chamber,” a game in which they threw rocks into a pit and screamed the sounds of people dying. One game of their own devising was modeled after the camp’s daily roll call and was called klepsi-klepsi, a common term for stealing. One playmate was blindfolded; then one of the others would step forward and hit him hard on the face; and then, with blindfold removed, the one who had been hit had to guess, from facial expressions or other evidence, who had hit him. To survive at Auschwitz, one had to be an expert at bluffing — for example, about stealing bread or about knowing of someone’s escape or resistance plans. Klepsi-klepsi may have been practice for that skill.

Gray goes on to explain why this sort of play is so important:

In play, whether it is the idyllic play we most like to envision or the play described by Eisen, children bring the realities of their world into a fictional context, where it is safe to confront them, to experience them, and to practice ways of dealing with them. Some people fear that violent play creates violent adults, but in reality the opposite is true. Violence in the adult world leads children, quite properly, to play at violence. How else can they prepare themselves emotionally, intellectually, and physically for reality? It is wrong to think that somehow we can reform the world for the future by controlling children’s play and controlling what they learn. If we want to reform the world, we have to reform the world; children will follow suit. The children must, and will, prepare themselves for the real world to which they must adapt to survive.

Like I said, fascinating.

World War II began 75 years ago today with Germany’s invasion of Poland. A few years back, Alan Taylor did a 20-part photographic retrospective of the war for In Focus, which is well worth the time to scroll through.

These images still give us glimpses into the experiences of our parents, grandparents and great grandparents, moments that shaped the world as it is today.

Life has a collection of color photos of the invasion of Poland. Time has a map dated Aug 28, 1939 that shows how Europe was preparing for war, including “Americans scuttle home”.

The Imitation Game is a historical drama about Alan Turing, focusing on his efforts in breaking the Enigma code during WWII. Benedict Cumberbatch plays Alan Turing. Here’s a trailer:

I watched the first episode of Band of Brothers last night to see if it held up (it does). The episode centers on the training and deployment to England of Easy Company of the 506th Parachute Infantry Regiment, led by Lt. Herbert Sobel. In the miniseries, Sobel is played by David Schwimmer and is depicted as a real hardass who earns the hatred of his men while pushing them to be the best company in the entire regiment.

In real life, Sobel rose to the rank of Lieutenant Colonel, fought in the Korean War, was awarded the Bronze Star, married and had three children. The part of Sobel’s Wikipedia entry about his later years is among the saddest things I have ever read:

In the late 1960s, Sobel shot himself in the head with a small-caliber pistol. The bullet entered his left temple, passed behind his eyes, and exited out the other side of his head. This severed his optic nerves and left him blind. He was later moved to a VA assisted living facility in Waukegan, Illinois. Sobel resided there for his last seventeen years until his death due to malnutrition on September 30, 1987. No services were held for Sobel after his death.

Rest in peace, Lieutenant Colonel Sobel.

Per Betteridge’s law of headlines, the answer to this is “no”, but it’s still an interesting yarn.

Among the many enduring mysteries of this period is the fate of the world’s most famous painting. It seems that Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa was among the paintings found in the Altaussee salt mine in the Austrian alps, which was converted by the Nazis into their secret stolen-art warehouse.

The painting only “seems” to have been found there because contradictory information has come down through history, and the Mona Lisa is not mentioned in any wartime document, Nazi or allied, as having been in the mine. Whether it may have been at Altaussee was a question only raised when scholars examined the postwar Special Operations Executive report on the activities of Austrian double agents working for the allies to secure the mine. This report states that the team “saved such priceless objects as the Louvre’s Mona Lisa”. A second document, from an Austrian museum near Altaussee dated 12 December 1945, states that “the Mona Lisa from Paris” was among “80 wagons of art and cultural objects from across Europe” taken into the mine.

The Mona Lisa was actually stolen in 1911, in one of the cleverest art heists ever pulled.

Jay Zeamer and a group of fellow misfits collectively called the Eager Beavers were an American photoreconnaissance team in the Pacific theater during WWII. They flew their beat-up B-17 bomber into enemy territory to collection reconnaissance photographs. Roger Cicala shares the engaging story of their most noteworthy photo.

The only crew that volunteered, of course, was Jay Zeamer and the Eager Beavers. One of the crew, bombardier Joseph Sarnovski, had absolutely no reason to volunteer. He’d already been in combat for 18 months and was scheduled to go home in 3 days. Being a photo mission, there was no need for a bombardier. But if his friends were going, he wanted to go, and one of the bombardier’s battle stations was to man the forward machine guns. They might need him, so he went.

They suspected the airstrip at Buka had been expanded and reinforced, but weren’t sure until they got close. As soon as the airfield came in sight, they saw numerous fighters taking off and heading their way. The logical thing to do would have been to turn right and head for home. They would be able to tell the intelligence officers about the increased number of planes at Buka even if they didn’t get photos.

But Zeamer and photographer William Kendrick knew that photos would be invaluable for subsequent planes attacking the base, and for Marines who were planning to invade the island later. Zeamer held the plane level (tilting the wings even one degree at that altitude could put the photograph half a mile off target) and Kendrick took his photos, which gave plenty of time for over 20 enemy fighters to get up to the altitude Old 666 was flying at.

(via petapixel)

A 7-minute time lapse video of the European front line changes during World War II, from the invasion of Poland to (spoilers!) the surrender of Germany.

Surprising to me how much of the war involves no shifting front lines…the map view really emphasizes this in a way that other WWII narratives do not. (via open culture)

Kevin Delaney, the head of Wayland High School’s history department, gave his 11th grade students an interesting challenge: find out everything you can about the person who owned a dusty briefcase full of papers that Delaney had found in the storage room. The man, Martin Joyce, turned out to have a life that spanned many significant events in history and his story provided the students with a personal lens into history.

Inside were the assorted papers — letters, military records, photos — left behind by a man named Martin W. Joyce, a long-since deceased West Roxbury resident who began his military career as an infantryman in World War I and ended it as commanding officer of the liberated Dachau concentration camp. Delaney could have contacted a university or a librarian and handed the trove of primary sources over to a researcher skilled in sorting through this kind of thing. Instead, he applied for a grant, and asked an archivist to come teach his students how to handle fragile historical materials. Then, for the next two years, he and his 11th grade American history students read through the documents, organized and uploaded them to the web, and wrote the biography of a man whom history nearly forgot, but who nonetheless witnessed a great deal of it.

“Joyce became the thread that went through our general studies,” Delaney says. “When we were studying World War I, we did the traditional World War I lessons and readings. And then stopped the clocks and thought, ‘What’s going on with Joyce in this period?’”

As the class repeatedly asked and answered that question, they slowly uncovered the life of a man who not only oversaw the liberated Dachau but also found himself a participant in an uncommon number of consequential events throughout Massachusetts and U.S. history. In a way Delaney couldn’t have imagined when he first popped open the suitcase that day, Joyce would turn out to be something akin to Boston’s own Forrest Gump — a perfect set of eyes through which to visit America’s past.

Fantastic, what a great story. My favorite tidbit is that after all the wars and stuff, he and his wife were on the Andrea Doria when it was struck by the Stockholm and sunk. Part of the students’ project was building a web site pertaining to Joyce’s life and includes scans of all the papers they discovered…it’s well worth looking through. (via @SlateVault)

An incredibly brave and cunning group of French prisoners of war were able to construct a camera inside the Nazi prison camp they were being held at and film their conditions.

Their rarely seen footage is called Sous Le Manteau (Clandestinely). So professional is it that on first viewing you would be forgiven for thinking it is a post-war reconstruction.

Prisoners filmed the camp secretly with a camera inside a hollowed-out dictionary. It is in fact a 30-minute documentary, shot in secret by the prisoners themselves. Risking death, they recorded it on a secret camera built from parts that were smuggled into the camp in sausages.

The prisoners had discovered that German soldiers would only check food sent in by cutting it down the middle. The parts were hidden in the ends.

The camera they built was concealed in a hollowed-out dictionary from the camp library. The spine of the book opened like a shutter. The 8mm reels on which the film was stored were then nailed into the heels of their makeshift shoes.

It gives an incredible insight into living conditions within the camp. The scant food they were given, the searches conducted without warning by the German soldiers. They filmed it all, even the searches, right under the noses of their guards.

A minute of the film is viewable on the BBC’s website. (via @DavidGrann)

German photographer Hugo Jaeger traveled around Poland after the Nazi invasion and documented daily life there. Life has a selection of Jaeger’s color photos from that time.

Why would Hugo Jaeger, a photographer dedicated to lionizing Adolf Hitler and the “triumphs” of the Third Reich, choose to immortalize conquered Jews in Warsaw and Kutno (a small town in central Poland) in such an uncharacteristic, intimate manner? Most German photographers working in the same era as Jaeger usually focused on the Wehrmacht; on Nazi leaders; and on the military victories the Reich was so routinely enjoying in the earliest days of the Second World War. Those pictures frequently document brutal acts of humiliation, even as they glorify German troops.

The photographs that Jaeger made in the German ghettos in occupied Poland, on the other hand, convey almost nothing of the triumphalism seen in so many of his other photographs. Here, in fact, there is virtually no German military presence at all. We see the devastation in the landscape of the German invasion of Poland, but very little of the “master race” itself.

It is, of course, impossible to fully recreate exactly what Jaeger had in mind, but from the reactions of the people portrayed in these images in Warsaw and Kutno, there appears to be surprising little hostility between the photographer and his subjects. Most of the people in these pictures, Poles and Jews, are smiling at the camera. They trust Jaeger, and are as curious about this man with a camera as he is about them. In this curiosity, there is no sense of hatred. The men, women and children on the other side of the lens and Jaeger look upon one another without the aggression and tension characteristic of the relationship between perpetrator and victim.

It’s still amazing the extent to which early color photography can transport us back to the past in a way that black & white photography or even video cannot.

This obituary of Count Robert de La Rochefoucauld has 4 or 5 paragraphs similar to the one below.

En route to his execution in Auxerre, La Rochefoucauld made a break, leaping from the back of the truck carrying him to his doom, and dodging the bullets fired by his two guards. Sprinting through the empty streets, he found himself in front of the Gestapo’s headquarters, where a chauffeur was pacing near a limousine bearing the swastika flag. Spotting the key in the ignition, La Rochefoucauld jumped in and roared off, following the Route Nationale past the prison he had left an hour earlier.

(via Stellar)

Soon after the US dropped two nuclear bomb on Japan in 1945, a group of physicists at the University of Pennsylvania decided to investigate for themselves how nuclear fission and the bomb might work using non-classified materials. In doing so, they ventured into classified territory and raised questions about the nature of science and secrecy.

To what degree would nuclear research become shackled by the requirements of national security? Would the open circulation of new scientific knowledge cease if that knowledge was relevant to nuclear fission? Those questions were hardly idle speculation: From the fall of 1945 through the summer of 1946, the US Congress was crafting new, unprecedented legislation that would legally define the bounds of open scientific research and even free speech. The idea of restricting open scientific communication “may seem drastic and far-reaching,” President Harry S. Truman argued in an October 1945 statement exhorting Congress to rapid action. But, he said, the atomic bomb “involves forces of nature too dangerous to fit into any of our usual concepts.”

The former Manhattan Project scientists who founded what would eventually become the Federation of American Scientists were adamantly opposed to keeping nuclear technology a closed field. From early on they argued that there was, as they put it, “no secret to be kept.” Attempting to control the spread of nuclear weapons by controlling scientific information would be fruitless: Soviet scientists were just as capable as US scientists when it came to discovering the truths of the physical world. The best that secrecy could hope to do would be to slightly impede the work of another nuclear power. Whatever time was bought by such impediment, they argued, would come at a steep price in US scientific productivity, because science required open lines of communication to flourish.

At the University of Pennsylvania were nine scientists sympathetic to that message. All had been involved with wartime work, but in the area of radar, not the bomb. Because they had not been part of the Manhattan Project in any way, they were under no legal obligation to maintain secrecy; they were simply informed private citizens. In the fall of 1945, they tried to figure out the technical details behind the bomb.

The @RealTimeWWII Twitter account is tweeting the events of World War II as they happened 72 years ago. A sample tweet from a few hours ago:

Germany has announced (again) that it will respect the neutrality of Belgium & Holland; “No German troops will enter the Low Countries”

Meanwhile back in 1668, Samuel Pepys is having trouble with his wife because he had a dalliance with the maid.

To dinner. The girle with us, but my wife troubled thereat to see her, and do tell me so, which troubles me, for I love the girle.

Matthew Porter’s photo composite Empire on the Platte is arresting.

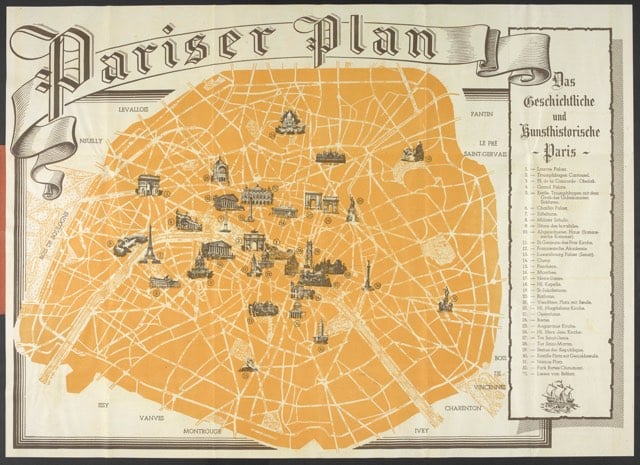

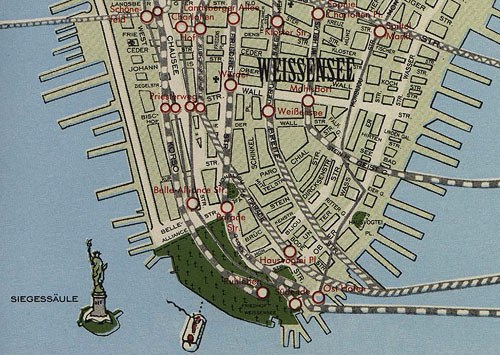

Pairs nicely with Melissa Gould’s Neu-York, “an obsessively detailed alternate-history map, imagining how Manhattan might have looked had the Nazis conquered it in World War II”.

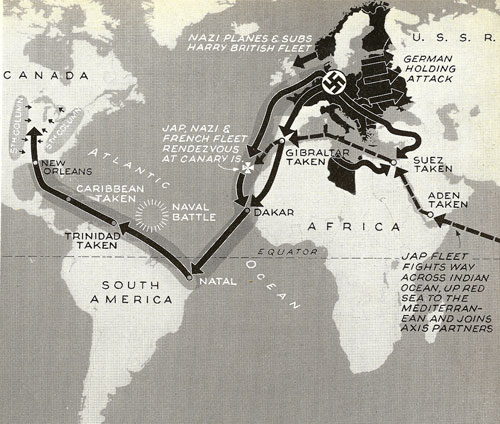

In 1942, Life magazine speculated about what an Axis invasion of North America might look like.

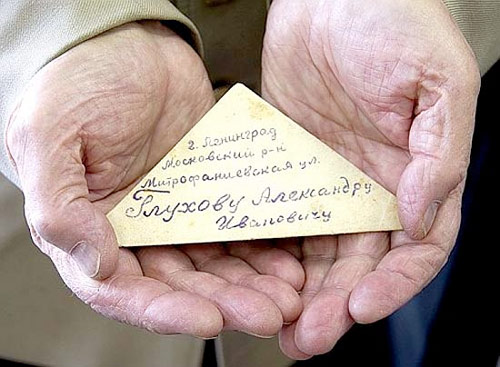

The standard form of Soviet war correspondence during WWII were letters folded into a triangular shape.

During the war, the mails were brought for free from the front to home. It could not have been differently, because probably the postage stamps would have been the last item the halting logistic support would have delivered to the front. Even so, postcards and envelopes were shortages. The soldiers’ genius has thus created, right in the first months of the war, the format that was a letter and its own envelope in one. The folding process is very similar to how we, in our childhood, folded our soldier’s shako, knowing nothing about the triangular soldier’s letters.

(via raul)

These color photos taken of London during WWII’s Battle of Britain are great.

Alan Taylor recently covered the Battle of Britain over at In Focus as well…I love this “business as usual” photo.

As part of his new-ish gig as editor of In Focus at The Atlantic, Alan Taylor is running a 20-week series of photo essays on World War II. The first essay, Before the War, has been posted and is excellent.

The years leading up to the declaration of war between the Axis and Allied powers in 1939 were tumultuous times for people across the globe. The Great Depression had started a decade before, leaving much of the world unemployed and desperate. Nationalism was sweeping through Germany, and it chafed against the punitive measures of the Versailles Treaty that had ended World War I. China and the Empire of Japan had been at war since Japanese troops invaded Manchuria in 1931. Germany, Italy, and Japan were testing the newly founded League of Nations with multiple invasions and occupations of nearby countries, and felt emboldened when they encountered no meaningful consequences. The Spanish Civil War broke out in 1936, becoming a rehearsal of sorts for the upcoming World War — Germany and Italy supported the nationalist rebels led by General Francisco Franco, and some 40,000 foreign nationals traveled to Spain to fight in what they saw as the larger war against fascism.

(thx, david)

Kamikaze pilot Masanobu Kuno wrote a farewell letter to his young son and daughter the day before he flew to his death in the Battle of Okinawa. From the translation:

Your father will become a god and watch you two closely. Both of you, study hard and help out your mother with work. I can’t be your horse to ride, but you two be good friends.

I should have a “crying at work” tag for posts like this.

Malcolm Gladwell tells us about Operation Mincemeat, a caper undertaken by British intelligence to fool the Hitler and the Nazis into thinking the Allied invasion of mainland Europe would come from through Greece and not Sicily.

It did not take long for word of the downed officer to make its way to German intelligence agents in the region. Spain was a neutral country, but much of its military was pro-German, and the Nazis found an officer in the Spanish general staff who was willing to help. A thin metal rod was inserted into the envelope; the documents were then wound around it and slid out through a gap, without disturbing the envelope’s seals. What the officer discovered was astounding. Major Martin was a courier, carrying a personal letter from Lieutenant General Archibald Nye, the vice-chief of the Imperial General Staff, in London, to General Harold Alexander, the senior British officer under Eisenhower in Tunisia. Nye’s letter spelled out what Allied intentions were in southern Europe. American and British forces planned to cross the Mediterranean from their positions in North Africa, and launch an attack on German-held Greece and Sardinia. Hitler transferred a Panzer division from France to the Peloponnese, in Greece, and the German military command sent an urgent message to the head of its forces in the region: “The measures to be taken in Sardinia and the Peloponnese have priority over any others.”

An amazingly extensive Flash presentation of the eastern front in Europe during World War II. It takes a while for the Flash to load because of all the resources but well worth the wait if you’re at all interested in WWII. (thx, reis)

Kseniya Simonova won Ukraine’s Got Talent 2009 competition with her dramatization of Germany’s invasion of Ukraine during WWII, performed with sand on a giant lightbox. Sounds like the cheesiest thing, but this performance is amazing.

Watch until at least 1:06…that’s when my mouth dropped open a bit. The entire audience was in tears by the end. (via @jessicadeva)

Rochus Misch, now 92, recollects that he was in Adolf Hitler’s bunker when the German dictator committed suicide.

“Then Bormann ordered Hitler’s door to be opened. I saw Hitler slumped with his head on the table. Eva Braun was lying on the sofa, with her head towards him. Her knees were drawn tightly up to her chest. She was wearing a dark blue dress with white frills. I will never forget it.

In remembrance of the mass destruction of life and property due to the dropping of the first atomic bomb on Hiroshima 64 years ago today, The Big Picture presents a typically excellent selection of photos.

Update: From Design Observer about a year ago, Hiroshima, The Lost Photographs.

As a follow-up to the excellent Band of Brothers, HBO, Steven Speilberg, and Tom Hanks have teamed up to make The Pacific, a 10-part miniseries about the fighting in the Pacific during WWII from the perspective of a group of US Marines. The first trailer for the series has been released:

(via sarahnomics)

Update: So of course HBO made YouTube remove the video of the trailer. But they put up a smaller crappier version on their own site so it’s all ok, right? (Why do media companies not like people spreading their advertising around? That’s the fucking goal, yes?) Anyway, in the meantime I changed the link to the video above with a new one that hasn’t been removed yet. And if that one gets removed, you can probably find the newest ones here. (thx, greg)

Dueling book reviews! (Sort of.) First, a pair of books suggest, contrary to Robert Oppenheimer’s post-war views, that the US is the only nation to have developed atomic weaponry and that all the other nuclear nations have gotten their information from the US program.

All paths stem from the United States, directly or indirectly. One began with Russian spies that deeply penetrated the Manhattan Project. Stalin was so enamored of the intelligence haul, Mr. Reed and Mr. Stillman note, that his first atom bomb was an exact replica of the weapon the United States had dropped on Nagasaki.

Moscow freely shared its atomic thefts with Mao Zedong, China’s leader. The book says that Klaus Fuchs, a Soviet spy in the Manhattan Project who was eventually caught and, in 1959, released from jail, did likewise. Upon gaining his freedom, the authors say, Fuchs gave the mastermind of Mao’s weapons program a detailed tutorial on the Nagasaki bomb. A half-decade later, China surprised the world with its first blast.

The book, in a main disclosure, discusses how China in 1982 made a policy decision to flood the developing world with atomic know-how. Its identified clients include Algeria, Pakistan and North Korea.

This week’s New Yorker contains an article about a third book that’s the culmination of more than a decade of research on the workings of the atomic bombs dropped on Japan (subscribers only). From the abstract:

Coster-Mullen’s book includes more than a hundred pages of declassified photographs from half a dozen government archives. Coster-Mullen, who is a truck driver by profession, sees his project as a diverting mental challenge. “This is nuclear archeology,” he says.

Coster-Mullen goes on to add that “the secret of the atomic bomb is how easy they are to make”. His hand-bound book, Atom Bombs, is available from Amazon.

Harper’s has a translated excerpt from a 1942 letter detailing a list of recipes used by the residents of Leningrad during the city’s blockage by the Nazis in WWII (subscribers only). In addition to mustard cakes and leather-belt soup, here’s this:

Soup from pets and domesticated animals

Meat is ranked by taste in the following order: dog, guinea pig, cat, rat. Gut the carcass, wash well and place in cold water. Add salt. Cook for one to three hours. For aroma: bay leaf, pepper, any sort of herbs, and, if available, grain.

A month after the bombing of Hiroshima in 1945, the US government imposed a code of censorship in Japan, which means that photos of the effects of the nuclear device are somewhat difficult to come by. Enter diner owner Don Levy of Watertown, MA.

One rainy night eight years ago, in Watertown, Massachusetts, a man was taking his dog for a walk. On the curb, in front of a neighbor’s house, he spotted a pile of trash: old mattresses, cardboard boxes, a few broken lamps. Amidst the garbage he caught sight of a battered suitcase. He bent down, turned the case on its side and popped the clasps.

He was surprised to discover that the suitcase was full of black-and-white photographs. He was even more astonished by their subject matter: devastated buildings, twisted girders, broken bridges — snapshots from an annihilated city. He quickly closed the case and made his way back home.

The photographs were taken by the US Strategic Bombing Survey immediately after the war and are now in the possession of the International Center of Photography. A copy of a report made by the US Strategic Bombing Survey is available online at the Truman Library.

André Zucca’s color photographs of Paris during the German occupation of WWII have provoked controversy because Zucca worked for a German propaganda magazine. But Richard Brody argues that Zucca’s photographs are true to the Paris of the time and don’t just show the “cheerful ease” of the city’s residents.

Certainly, Zucca couldn’t get the whole story: he photographed Jews wearing the star but couldn’t show the roundups or the deportation to Auschwitz; he could show German soldiers but couldn’t show the arrest, torture, and execution of resisters. He couldn’t, but nobody could; the problem wasn’t that he worked for a propaganda rag: photographers who actively worked for the Resistance couldn’t do it either. But what he did do was to capture the paradoxes of the Occupation, where horror and pleasure coexisted in shockingly close proximity, where the active resistance to Nazi occupation was in fact far less prevalent than the feigned daily oblivion of those who kept their heads down and tried to cope.

Stay Connected