I’m just going to go ahead and say it right up front here: if you had certain expectations in May/June about how the pandemic was going to end in the US (or was even thinking it was over), you need to throw much of that mindset in the trash and start again because the Delta variant of SARS-CoV-2 has changed the game. I know this sucks to hear,1 but Delta is sufficiently different that we need to reset and stop assuming we can solely rely on the vaccines to stop Covid-19 from spreading. Ed Yong’s typically excellent piece on how delta has changed the pandemic’s endgame is helping me wrap my head around this.

But something is different now — the virus. “The models in late spring were pretty consistent that we were going to have a ‘normal’ summer,” Samuel Scarpino of the Rockefeller Foundation, who studies infectious-disease dynamics, told me. “Obviously, that’s not where we are.” In part, he says, people underestimated how transmissible Delta is, or what that would mean. The original SARS-CoV-2 virus had a basic reproduction number, or R0, of 2 to 3, meaning that each infected person spreads it to two or three people. Those are average figures: In practice, the virus spread in uneven bursts, with relatively few people infecting large clusters in super-spreading events. But the CDC estimates that Delta’s R0 lies between 5 and 9, which “is shockingly high,” Eleanor Murray, an epidemiologist at Boston University, told me. At that level, “its reliance on super-spreading events basically goes away,” Scarpino said.

In simple terms, many people who caught the original virus didn’t pass it to anyone, but most people who catch Delta create clusters of infection. That partly explains why cases have risen so explosively. It also means that the virus will almost certainly be a permanent part of our lives, even as vaccines blunt its ability to cause death and severe disease.

And a reminder, as we “argue over small measures” here in the US, that most of the world is in a much worse place:

Pandemics end. But this one is not yet over, and especially not globally. Just 16 percent of the world’s population is fully vaccinated. Many countries, where barely 1 percent of people have received a single dose, are “in for a tough year of either lockdowns or catastrophic epidemics,” Adam Kucharski, the infectious-disease modeler, told me. The U.S. and the U.K. are further along the path to endemicity, “but they’re not there yet, and that last slog is often the toughest,” he added. “I have limited sympathy for people who are arguing over small measures in rich countries when we have uncontrolled epidemics in large parts of the world.”

Where I think Yong’s piece stumbles a little is in its emphasis of the current vaccines’ protection against infection from Delta. As David Wallace-Wells explains in his piece Don’t Panic, But Breakthrough Cases May Be a Bigger Problem Than You’ve Been Told, vaccines still offer excellent protection against severe infection, hospitalization, and death, but there is evidence that breakthrough infections are more common than many public health officials are saying. The problem lies with the use of statistics from before vaccines and Delta were prevalent:

Almost all of these calculations about the share of breakthrough cases have been made using year-to-date 2021 data, which include several months before mass vaccination (when by definition vanishingly few breakthrough cases could have occurred) during which time the vast majority of the year’s total cases and deaths took place (during the winter surge). This is a corollary to the reassuring principle you might’ve heard, over the last few weeks, that as vaccination levels grow we would expect the percentage of vaccinated cases will, too — the implication being that we shouldn’t worry too much over panicked headlines about the relative share of vaccinated cases in a state or ICU but instead focus on the absolute number of those cases in making a judgment about vaccine protection across a population. This is true. But it also means that when vaccination levels were very low, there were inevitably very few breakthrough cases, too. That means that to calculate a prevalence ratio for cases or deaths using the full year’s data requires you to effectively divide a numerator of four months of data by a denominator of seven months of data. And because those first few brutal months of the year were exceptional ones that do not reflect anything like the present state of vaccination or the disease, they throw off the ratios even further. Two-thirds of 2021 cases and 80 percent of deaths came before April 1, when only 15 percent of the country was fully vaccinated, which means calculating year-to-date ratios means possibly underestimating the prevalence of breakthrough cases by a factor of three and breakthrough deaths by a factor of five. And if the ratios are calculated using data sets that end before the Delta surge, as many have been, that adds an additional distortion, since both breakthrough cases and severe illness among the vaccinated appear to be significantly more common with this variant than with previous ones.

Vaccines are still the best way to protect yourself and your community from Covid-19. The vaccines are still really good, better than we could have hoped for. But they’re not magic and with the rise of Delta (and potentially worse variants on the horizon if the virus is allowed to continue to spread unchecked and mutate), we need to keep doing the other things (masking, distancing, ventilation, etc.) in order to keep the virus in check and avoid lockdowns, school closings, outbreaks, and mass death. We’ve got the tools; we just need to summon the will and be in the right mindset.

The Kottke Ride Home podcast has been humming away since August and host Jackson Bird has been sharing some great stuff lately. From today’s show comes this New York magazine piece by David Wallace-Wells about the stunning speed with which the Covid-19 vaccine was developed:

You may be surprised to learn that of the trio of long-awaited coronavirus vaccines, the most promising, Moderna’s mRNA-1273, which reported a 94.5 percent efficacy rate on November 16, had been designed by January 13. This was just two days after the genetic sequence had been made public in an act of scientific and humanitarian generosity that resulted in China’s Yong-Zhen Zhang’s being temporarily forced out of his lab. In Massachusetts, the Moderna vaccine design took all of one weekend. It was completed before China had even acknowledged that the disease could be transmitted from human to human, more than a week before the first confirmed coronavirus case in the United States. By the time the first American death was announced a month later, the vaccine had already been manufactured and shipped to the National Institutes of Health for the beginning of its Phase I clinical trial.

Monday’s show featured the intrigue behind the discovery of a real life treasure:

And if you look back to last week, Jackson clued us in to Radiooooo (“The Musical Time Machine”), Tetris championships, China’s Chang’e 5 mission to the Moon, and DeepMind’s AI breakthrough in protein folding.

If any or all of that sounds interesting to you, you can subscribe to Kottke Ride Home right here or in your favorite podcast app.

As Ed Yong notes in his helpful overview of the pandemic, this is such a huge and quickly moving event that it’s difficult to know what’s happening. Lately, I’ve been seeking information on Covid-19’s presenting symptoms after seeing a bunch of anecdotal data from various sources.

In the early days of the epidemic (January, February, and into March), people were told by the CDC and other public health officials to watch out for three specific symptoms: fever, a dry cough, and shortness of breath. In many areas, testing was restricted to people who exhibited only those symptoms. Slowly, as more data is gathered, the profile of the presenting symptoms has started to shift. From a New York magazine piece by David Wallace-Wells on Monday:

While the CDC does list fever as the top symptom of COVID-19, so confidently that for weeks patients were turned away from testing sites if they didn’t have an elevated temperature, according to the Journal of the American Medical Association, as many as 70 percent of patients sick enough to be admitted to New York State’s largest hospital system did not have a fever.

Over the past few months, Boston’s Brigham and Women’s Hospital has been compiling and revising, in real time, treatment guidelines for COVID-19 which have become a trusted clearinghouse of best-practices information for doctors throughout the country. According to those guidelines, as few as 44 percent of coronavirus patients presented with a fever (though, in their meta-analysis, the uncertainty is quite high, with a range of 44 to 94 percent). Cough is more common, according to Brigham and Women’s, with between 68 percent and 83 percent of patients presenting with some cough — though that means as many as three in ten sick enough to be hospitalized won’t be coughing. As for shortness of breath, the Brigham and Women’s estimate runs as low as 11 percent. The high end is only 40 percent, which would still mean that more patients hospitalized for COVID-19 do not have shortness of breath than do. At the low end of that range, shortness of breath would be roughly as common among COVID-19 patients as confusion (9 percent), headache (8 to 14 percent), and nausea and diarrhea (3 to 17 percent).

Recently, as noted by the Washington Post, the CDC has changed their list of Covid-19 symptoms to watch out for. They now list two main symptoms (cough & shortness of breath) and several additional symptoms (fever, chills, repeated shaking with chills, muscle pain, headache, sore throat, new loss of taste or smell). They also note that “this list is not all inclusive”. Compare that with their list from mid-February.

In addition, there’s evidence that children might have different symptoms (including stomach issues or diarrhea), doctors are reporting seeing “COVID toes” on some patients, and you might want to look at earlier data from these three studies about symptoms observed in Wuhan and greater China.

The reason I’m interested in this shift in presenting symptoms is that on the last day or two of my trip to Asia, I got sick — and I’ve been wondering if it was Covid-19.

Here’s the timeline: starting on Jan 21, I was in Saigon, Vietnam for two weeks, then in Singapore for 4 days, and then Doha, Qatar for 48 hours. The day I landed in Doha, Feb 9, I started to feel a little off, and definitely felt sick the next day. I had a sore throat, headache, and congestion (stuffy nose) for the first few days. There was also some fatigue/tiredness but I was jetlagged too so… All the symptoms were mild and it felt like a normal cold to me. Here’s how I wrote about it in my travelogue:

I got sick on the last day of the trip, which turned into a full-blown cold when I got home. I dutifully wore my mask on the plane and in telling friends & family about how I was feeling, I felt obliged to text “***NOT*** coronavirus, completely different symptoms!!”

I flew back to the US on Feb 11 (I wore a mask the entire time in the Doha airport, on the plane, and even in the Boston airport, which no one else was doing). I lost my sense of taste and smell for about 2 days, which was a little unnerving but has happened to me with past colds. At no point did I have even the tiniest bit of fever or shortness of breath. The illness did drag on though — I felt run-down for a few weeks and a very slight cough that developed about a week and a half after I got sick lingered for weeks.

According to guidance from the WHO, CDC, and public health officials at the time, none of my initial symptoms were a match for Covid-19. I thought about getting a test or going to the doctor, but in the US in mid-February, and especially in Vermont, there were no tests available for someone with a mild cold and no fever. But looking at the CDC’s current list of symptoms — which include headache, sore throat, and new loss of taste or smell — and considering that I’d been in Vietnam and Singapore when cases were reported in both places, it seems plausible to me that my illness could have been a mild case of Covid-19. Hopefully it wasn’t, but I’ll be getting an antibody test once they are (hopefully) more widely available, even though the results won’t be super reliable.

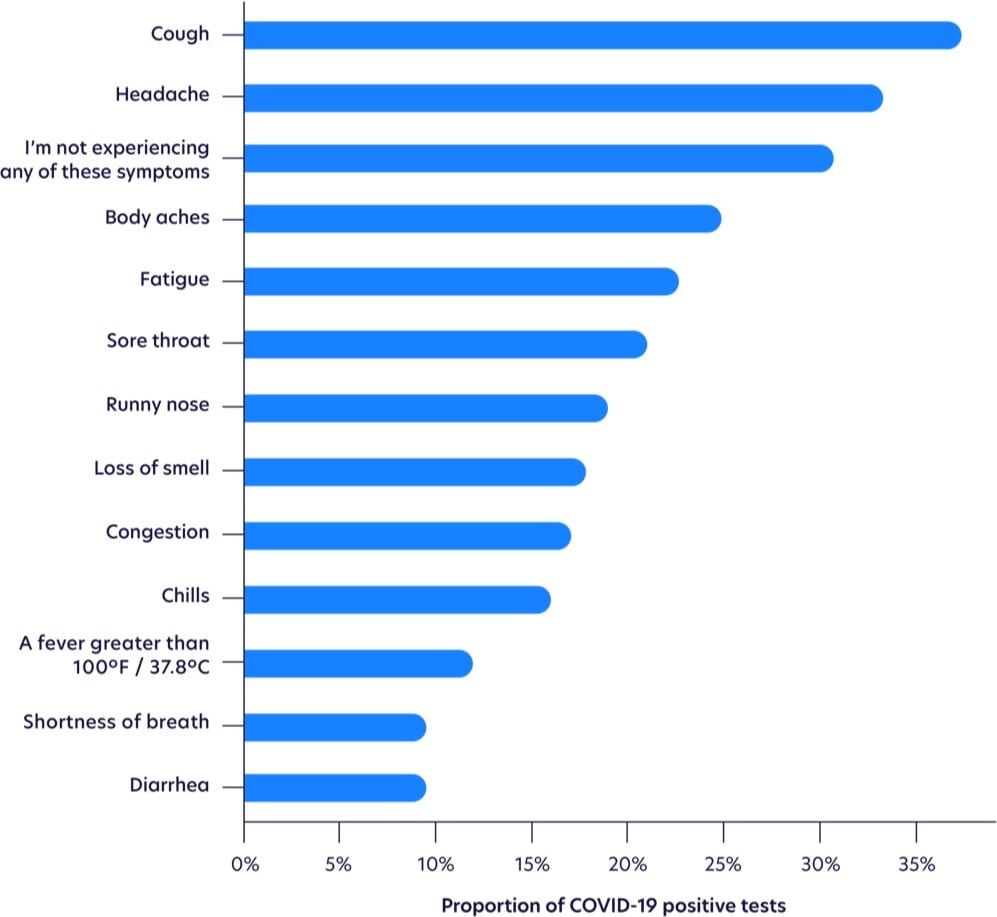

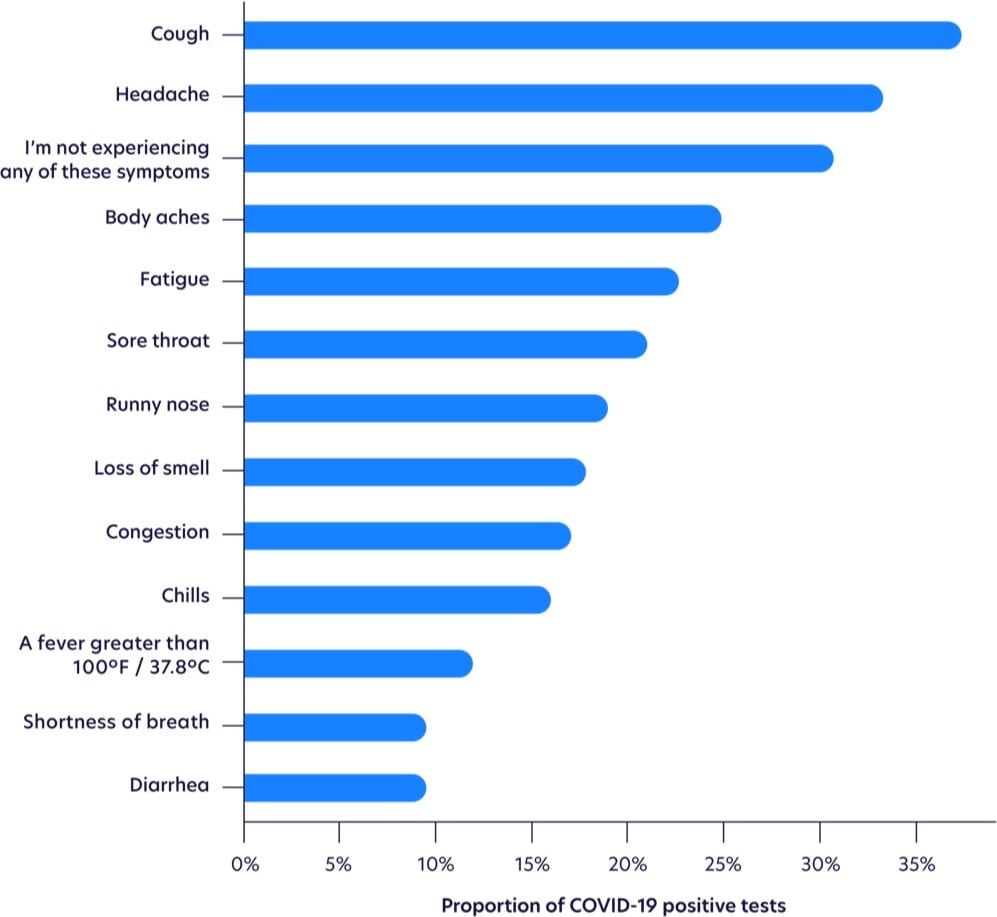

Update: More on the changing profile of Covid-19 symptoms from a sample size of more than 30,000 tests.

Fever is waaay down on the list.

While not as common as other symptoms, loss of smell was the most highly correlated with testing positive, as shown with odds ratios below, after adjusting for age and gender. Those with loss of smell were more likely to test positive for COVID-19 than those with a high fever.

Seeing this makes me think more than ever that I had it. I had three of the top five symptoms, plus an eventual cough (the most common symptom) and a loss of smell & taste (the most highly correlated symptom). The timing of the onset of my symptoms (my first day in Qatar) indicates that I probably got infected on my last day in Vietnam, in transit from Vietnam to Singapore (1 2-hr plane ride, 2 airports, 1 taxi, 1 train ride), or on my first day in Singapore. But I went to so many busy places during that time that it’s impossible to know where I might have gotten infected (or who I then went on to unwittingly infect).

Update: A few weeks ago, I noticed some horizontal lines on several of my toenails, a phenomenon I’d never seen before. When I finally googled it, I discovered they’re called Beau’s lines and they can show up when the body has been stressed by illness or disease. Hmm. From the Wikipedia page:

Some other reasons for these lines include trauma, coronary occlusion, hypocalcaemia, and skin disease. They may be a sign of systemic disease, or may also be caused by an illness of the body, as well as drugs used in chemotherapy, or malnutrition. Beau’s lines can also be seen one to two months after the onset of fever in children with Kawasaki disease.

From the Mayo Clinic:

Conditions associated with Beau’s lines include uncontrolled diabetes and peripheral vascular disease, as well as illnesses associated with a high fever, such as scarlet fever, measles, mumps and pneumonia.

From the estimated growth of my nails, it seems as though whatever disruption that caused the Beau’s lines happened 5-6 months ago, which lines up with my early February illness that I believe was Covid-19. Covid-19 can definitely affect the vascular systems of infected persons. Kawasaki disease is a vascular disease and a similar syndrome in children resulting from SARS-CoV-2 exposure is currently under investigation. And here’s a paper from December 1971 that tracked the development of Beau’s lines in several people who were ill during the 1968 flu pandemic (an H3N2 strain of the influenza A virus) — coronaviruses and influenza viruses are different but this is still an indicator that viruses can result in Beau’s lines. “Covid toe” has been observed in many Covid-19 patients. Harvard dermatologist and epidemiologist Dr. Esther Freeman reports that people may be experiencing hair loss due to Covid-19.

I couldn’t find any scientific literature about the possible correlation of Covid-19 and Beau’s lines, but I did find some suggestive anecdotal information. I found several people on Twitter who noticed lines in their nails (both fingers and toes) and who also have confirmed or suspected cases of Covid-19. And if you go to Google’s search bar and type “Beau’s lines c”, 3 of the 10 autocomplete suggestions are related to Covid-19, which indicates that people are searching for it (but not enough to register on Google Trends).

But I am definitely intrigued. Are dermatologists and podiatrists seeing Beau’s lines on patients who have previously tested positive for Covid-19? Have people who have tested positive noticed them? Email me at [email protected] if you have any info about this; I’d love to get to the bottom of this.

David Wallace-Wells, who you may remember from his 2017 New York magazine piece, has written an opinion piece about climate change for the NY Times called Time to Panic. In it, he urges that it’s time for urgent human action on climate change…time to stop treating it like a problem and start treating it like the crisis it is.

The age of climate panic is here. Last summer, a heat wave baked the entire Northern Hemisphere, killing dozens from Quebec to Japan. Some of the most destructive wildfires in California history turned more than a million acres to ash, along the way melting the tires and the sneakers of those trying to escape the flames. Pacific hurricanes forced three million people in China to flee and wiped away almost all of Hawaii’s East Island.

We are living today in a world that has warmed by just one degree Celsius (1.8 degrees Fahrenheit) since the late 1800s, when records began on a global scale. We are adding planet-warming carbon dioxide to the atmosphere at a rate faster than at any point in human history since the beginning of industrialization.

In October, the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change released what has become known as its “Doomsday” report — “a deafening, piercing smoke alarm going off in the kitchen,” as one United Nations official described it — detailing climate effects at 1.5 and two degrees Celsius of warming (2.7 and 3.6 degrees Fahrenheit). At the opening of a major United Nations conference two months later, David Attenborough, the mellifluous voice of the BBC’s “Planet Earth” and now an environmental conscience for the English-speaking world, put it even more bleakly: “If we don’t take action,” he said, “the collapse of our civilizations and the extinction of much of the natural world is on the horizon.”

Scientists have felt this way for a while. But they have not often talked like it. For decades, there were few things with a worse reputation than “alarmism” among those studying climate change.

This is a bit strange. You don’t typically hear from public health experts about the need for circumspection in describing the risks of carcinogens, for instance. The climatologist James Hansen, who testified before Congress about global warming in 1988, has called the phenomenon “scientific reticence” and chastised his colleagues for it — for editing their own observations so conscientiously that they failed to communicate how dire the threat actually was.

This essay is adapted from Wallace-Wells’ new book The Uninhabitable Earth, which is out tomorrow:

In his travelogue of our near future, David Wallace-Wells brings into stark relief the climate troubles that await — food shortages, refugee emergencies, and other crises that will reshape the globe. But the world will be remade by warming in more profound ways as well, transforming our politics, our culture, our relationship to technology, and our sense of history. It will be all-encompassing, shaping and distorting nearly every aspect of human life as it is lived today.

After talking with dozens of climatologists and related researchers, David Wallace-Wells writes about what will happen to the Earth and human civilization without taking “aggressive action” on slowing climate change. It is a sobering piece.

Since 1980, the planet has experienced a 50-fold increase in the number of places experiencing dangerous or extreme heat; a bigger increase is to come. The five warmest summers in Europe since 1500 have all occurred since 2002, and soon, the IPCC warns, simply being outdoors that time of year will be unhealthy for much of the globe. Even if we meet the Paris goals of two degrees warming, cities like Karachi and Kolkata will become close to uninhabitable, annually encountering deadly heat waves like those that crippled them in 2015. At four degrees, the deadly European heat wave of 2003, which killed as many as 2,000 people a day, will be a normal summer. At six, according to an assessment focused only on effects within the U.S. from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, summer labor of any kind would become impossible in the lower Mississippi Valley, and everybody in the country east of the Rockies would be under more heat stress than anyone, anywhere, in the world today. As Joseph Romm has put it in his authoritative primer Climate Change: What Everyone Needs to Know, heat stress in New York City would exceed that of present-day Bahrain, one of the planet’s hottest spots, and the temperature in Bahrain “would induce hyperthermia in even sleeping humans.” The high-end IPCC estimate, remember, is two degrees warmer still.

Carbon is not only warming the atmosphere, it’s also polluting it.

Our lungs need oxygen, but that is only a fraction of what we breathe. The fraction of carbon dioxide is growing: It just crossed 400 parts per million, and high-end estimates extrapolating from current trends suggest it will hit 1,000 ppm by 2100. At that concentration, compared to the air we breathe now, human cognitive ability declines by 21 percent.

Our climate is supposed to move slowly, in concert with many other slow moving things like ecosystems, evolution, global economies, politics, and civilizations. When the pace of climate change quickens? A lot of those slow moving things are going to break. Heat, drought, famine, coastal flooding, pollution, disease, war, forced migration, economic collapse…humanity will survive, but the worst case scenario is not pretty. And of course, the most vulnerable among us — the poor, young children, the elderly, pregnant women, the disabled, and the otherwise disadvantaged — will undergo the most suffering.

Update: And once again, addressing climate change isn’t about saving the planet, it’s about preserving humanity and preventing human suffering. As Seth Michaels tweeted: “‘the planet’ will be fine. the patterns and structures that determine where we live, what we eat, how we get along? *that’s* what’s at stake”. (via @lauraolin)

Update: A piece like this was going to be controversial and some of the responses are worth reading.

Climate scientist Michael Mann:

I have to say that I am not a fan of this sort of doomist framing. It is important to be up front about the risks of unmitigated climate change, and I frequently criticize those who understate the risks. But there is also a danger in overstating the science in a way that presents the problem as unsolvable, and feeds a sense of doom, inevitability and hopelessness.

The article argues that climate change will render the Earth uninhabitable by the end of this century. Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence. The article fails to produce it.

Eric Holthaus: Stop scaring people about climate change. It doesn’t work.

The real problem is that time and time and time again, psychology researchers have found that trying to scare people into action usually backfires. Presented with the idea that the planet that gives us life might be dying, parts of our brain shut down. We are unable to think logically.

Our brain’s limbic system is hard-wired to prioritize these kinds of threats, so we shift into fight-or-flight mode. And because the odds look stacked against us, most choose to flee. If anything, strategies like this make the problem worse. They take people willing to read something like “The Uninhabitable Earth” and essentially remove them from the pool of people working on real-world solutions.

Robinson Meyer: Are We as Doomed as That New York Magazine Article Says?

Many climate scientists and professional science communicators say no. Wallace-Wells’s article, they say, often flies beyond the realm of what researchers think is likely. I have to agree with them.

At key points in his piece, Wallace-Wells posits facts that mainstream climate science cannot support. In the introduction, he suggests that the world’s permafrost will belch all of its methane into the atmosphere as it melts, accelerating the planet’s warming in the decades to come. We don’t know everything about methane yet, but the picture does not seem this bleak. Melting permafrost will emit methane, and methane is an ultra-potent greenhouse gas, but scientists do not think so much it will escape in the coming century.

Andrew Freedman: Do not accept New York Mag’s climate change doomsday scenario.

In several places, the story either exaggerates the evidence or gets the science flat-out wrong. This is unfortunate, because it detracts from a well-written, attention-grabbing piece. It’s still worth reading, but with a sharp critical eye.

In recent years, scientific evidence has solidified around central findings, showing that sea level rise is likely to be far more severe during the rest of this century than initially anticipated, and that key temperature thresholds may be crossed that make life difficult for some kinds of plants and animals to survive in certain places.

Stay Connected