The Changing Profile of Covid-19’s Presenting Symptoms

As Ed Yong notes in his helpful overview of the pandemic, this is such a huge and quickly moving event that it’s difficult to know what’s happening. Lately, I’ve been seeking information on Covid-19’s presenting symptoms after seeing a bunch of anecdotal data from various sources.

In the early days of the epidemic (January, February, and into March), people were told by the CDC and other public health officials to watch out for three specific symptoms: fever, a dry cough, and shortness of breath. In many areas, testing was restricted to people who exhibited only those symptoms. Slowly, as more data is gathered, the profile of the presenting symptoms has started to shift. From a New York magazine piece by David Wallace-Wells on Monday:

While the CDC does list fever as the top symptom of COVID-19, so confidently that for weeks patients were turned away from testing sites if they didn’t have an elevated temperature, according to the Journal of the American Medical Association, as many as 70 percent of patients sick enough to be admitted to New York State’s largest hospital system did not have a fever.

Over the past few months, Boston’s Brigham and Women’s Hospital has been compiling and revising, in real time, treatment guidelines for COVID-19 which have become a trusted clearinghouse of best-practices information for doctors throughout the country. According to those guidelines, as few as 44 percent of coronavirus patients presented with a fever (though, in their meta-analysis, the uncertainty is quite high, with a range of 44 to 94 percent). Cough is more common, according to Brigham and Women’s, with between 68 percent and 83 percent of patients presenting with some cough — though that means as many as three in ten sick enough to be hospitalized won’t be coughing. As for shortness of breath, the Brigham and Women’s estimate runs as low as 11 percent. The high end is only 40 percent, which would still mean that more patients hospitalized for COVID-19 do not have shortness of breath than do. At the low end of that range, shortness of breath would be roughly as common among COVID-19 patients as confusion (9 percent), headache (8 to 14 percent), and nausea and diarrhea (3 to 17 percent).

Recently, as noted by the Washington Post, the CDC has changed their list of Covid-19 symptoms to watch out for. They now list two main symptoms (cough & shortness of breath) and several additional symptoms (fever, chills, repeated shaking with chills, muscle pain, headache, sore throat, new loss of taste or smell). They also note that “this list is not all inclusive”. Compare that with their list from mid-February.

In addition, there’s evidence that children might have different symptoms (including stomach issues or diarrhea), doctors are reporting seeing “COVID toes” on some patients, and you might want to look at earlier data from these three studies about symptoms observed in Wuhan and greater China.

The reason I’m interested in this shift in presenting symptoms is that on the last day or two of my trip to Asia, I got sick — and I’ve been wondering if it was Covid-19.

Here’s the timeline: starting on Jan 21, I was in Saigon, Vietnam for two weeks, then in Singapore for 4 days, and then Doha, Qatar for 48 hours. The day I landed in Doha, Feb 9, I started to feel a little off, and definitely felt sick the next day. I had a sore throat, headache, and congestion (stuffy nose) for the first few days. There was also some fatigue/tiredness but I was jetlagged too so… All the symptoms were mild and it felt like a normal cold to me. Here’s how I wrote about it in my travelogue:

I got sick on the last day of the trip, which turned into a full-blown cold when I got home. I dutifully wore my mask on the plane and in telling friends & family about how I was feeling, I felt obliged to text “***NOT*** coronavirus, completely different symptoms!!”

I flew back to the US on Feb 11 (I wore a mask the entire time in the Doha airport, on the plane, and even in the Boston airport, which no one else was doing). I lost my sense of taste and smell for about 2 days, which was a little unnerving but has happened to me with past colds. At no point did I have even the tiniest bit of fever or shortness of breath. The illness did drag on though — I felt run-down for a few weeks and a very slight cough that developed about a week and a half after I got sick lingered for weeks.

According to guidance from the WHO, CDC, and public health officials at the time, none of my initial symptoms were a match for Covid-19. I thought about getting a test or going to the doctor, but in the US in mid-February, and especially in Vermont, there were no tests available for someone with a mild cold and no fever. But looking at the CDC’s current list of symptoms — which include headache, sore throat, and new loss of taste or smell — and considering that I’d been in Vietnam and Singapore when cases were reported in both places, it seems plausible to me that my illness could have been a mild case of Covid-19. Hopefully it wasn’t, but I’ll be getting an antibody test once they are (hopefully) more widely available, even though the results won’t be super reliable.

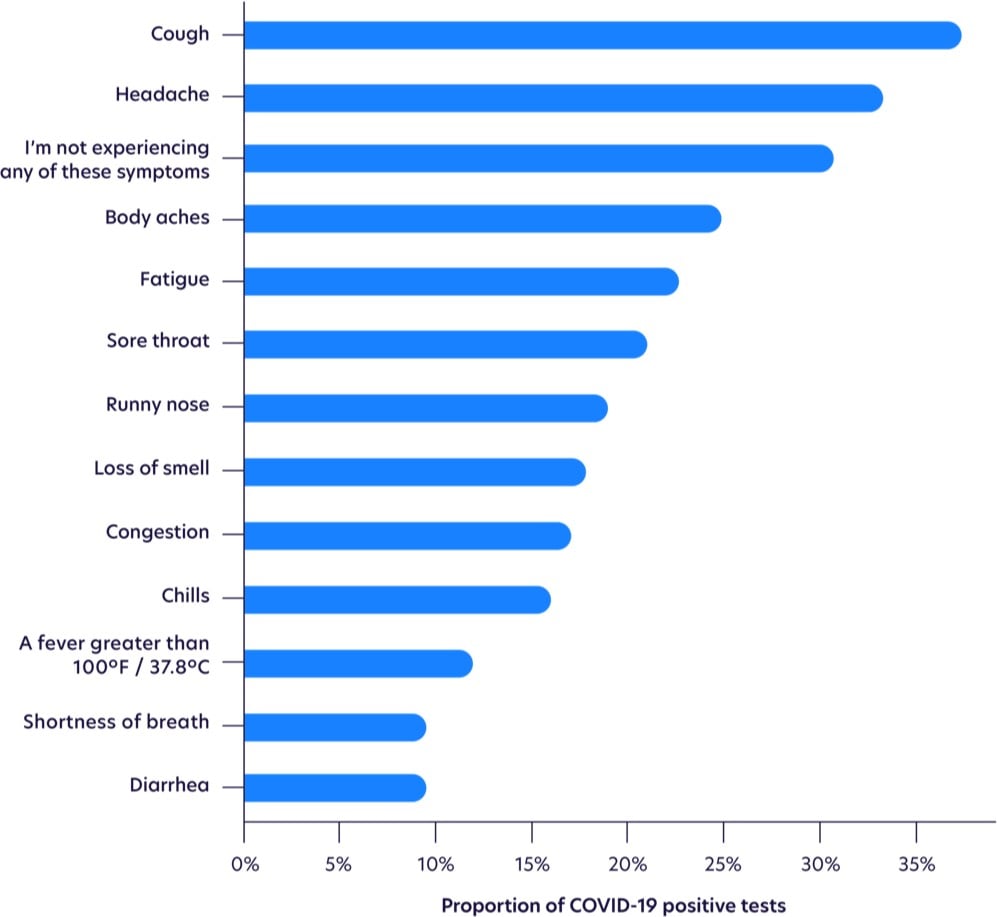

Update: More on the changing profile of Covid-19 symptoms from a sample size of more than 30,000 tests.

Fever is waaay down on the list.

While not as common as other symptoms, loss of smell was the most highly correlated with testing positive, as shown with odds ratios below, after adjusting for age and gender. Those with loss of smell were more likely to test positive for COVID-19 than those with a high fever.

Seeing this makes me think more than ever that I had it. I had three of the top five symptoms, plus an eventual cough (the most common symptom) and a loss of smell & taste (the most highly correlated symptom). The timing of the onset of my symptoms (my first day in Qatar) indicates that I probably got infected on my last day in Vietnam, in transit from Vietnam to Singapore (1 2-hr plane ride, 2 airports, 1 taxi, 1 train ride), or on my first day in Singapore. But I went to so many busy places during that time that it’s impossible to know where I might have gotten infected (or who I then went on to unwittingly infect).

Update: A few weeks ago, I noticed some horizontal lines on several of my toenails, a phenomenon I’d never seen before. When I finally googled it, I discovered they’re called Beau’s lines and they can show up when the body has been stressed by illness or disease. Hmm. From the Wikipedia page:

Some other reasons for these lines include trauma, coronary occlusion, hypocalcaemia, and skin disease. They may be a sign of systemic disease, or may also be caused by an illness of the body, as well as drugs used in chemotherapy, or malnutrition. Beau’s lines can also be seen one to two months after the onset of fever in children with Kawasaki disease.

From the Mayo Clinic:

Conditions associated with Beau’s lines include uncontrolled diabetes and peripheral vascular disease, as well as illnesses associated with a high fever, such as scarlet fever, measles, mumps and pneumonia.

From the estimated growth of my nails, it seems as though whatever disruption that caused the Beau’s lines happened 5-6 months ago, which lines up with my early February illness that I believe was Covid-19. Covid-19 can definitely affect the vascular systems of infected persons. Kawasaki disease is a vascular disease and a similar syndrome in children resulting from SARS-CoV-2 exposure is currently under investigation. And here’s a paper from December 1971 that tracked the development of Beau’s lines in several people who were ill during the 1968 flu pandemic (an H3N2 strain of the influenza A virus) — coronaviruses and influenza viruses are different but this is still an indicator that viruses can result in Beau’s lines. “Covid toe” has been observed in many Covid-19 patients. Harvard dermatologist and epidemiologist Dr. Esther Freeman reports that people may be experiencing hair loss due to Covid-19.

I couldn’t find any scientific literature about the possible correlation of Covid-19 and Beau’s lines, but I did find some suggestive anecdotal information. I found several people on Twitter who noticed lines in their nails (both fingers and toes) and who also have confirmed or suspected cases of Covid-19. And if you go to Google’s search bar and type “Beau’s lines c”, 3 of the 10 autocomplete suggestions are related to Covid-19, which indicates that people are searching for it (but not enough to register on Google Trends).

But I am definitely intrigued. Are dermatologists and podiatrists seeing Beau’s lines on patients who have previously tested positive for Covid-19? Have people who have tested positive noticed them? Email me at [email protected] if you have any info about this; I’d love to get to the bottom of this.

Stay Connected