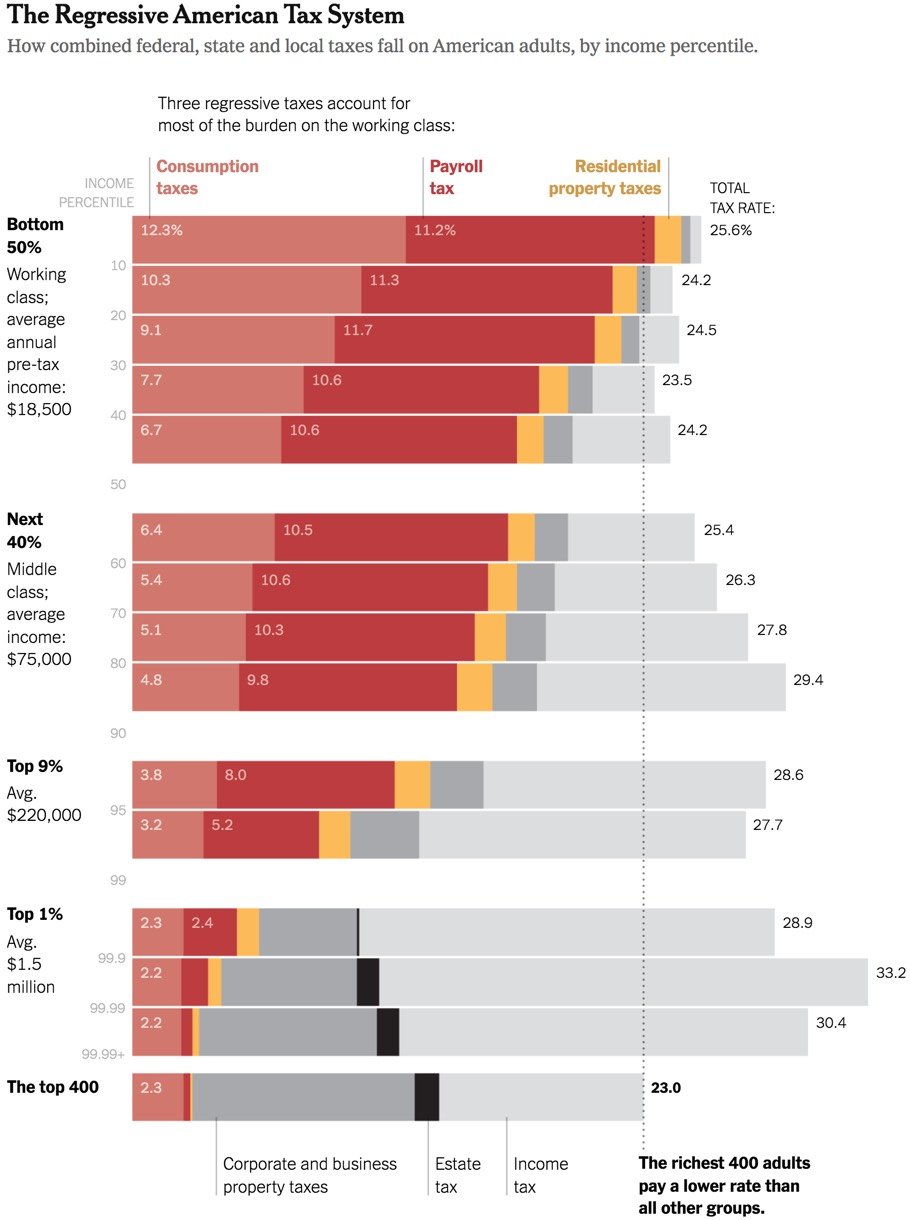

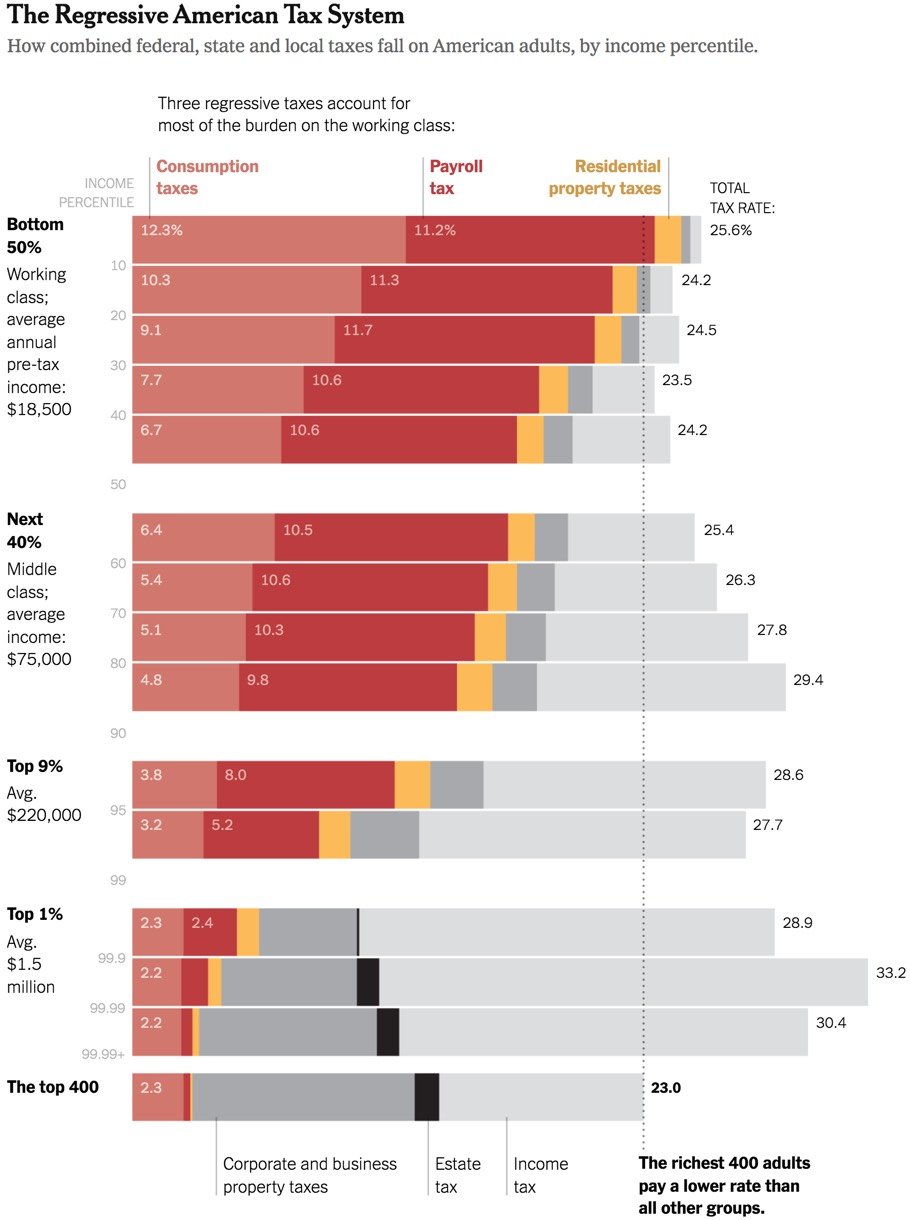

On Monday, I posted a link to David Leonhardt’s NY Times piece, The Rich Really Do Pay Lower Taxes Than You.

For the first time on record, the 400 wealthiest Americans last year paid a lower total tax rate — spanning federal, state and local taxes — than any other income group, according to newly released data. That’s a sharp change from the 1950s and 1960s, when the wealthy paid vastly higher tax rates than the middle class or poor. Since then, taxes that hit the wealthiest the hardest — like the estate tax and corporate tax — have plummeted, while tax avoidance has become more common. President Trump’s 2017 tax cut, which was largely a handout to the rich, plays a role, too. It helped push the tax rate on the 400 wealthiest households below the rates for almost everyone else.

The result is a tax system that is much less progressive than it used to be. And unjust. The economists who compiled this data, Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman, have written a book called The Triumph of Injustice: How the Rich Dodge Taxes and How to Make Them Pay. In this piece called How to Tax Our Way Back to Justice, the pair lay out the problem and how we can fix it to make our tax system more just for the majority of Americans.

The good news is that we can fix tax injustice, right now. There is nothing inherent in modern technology or globalization that destroys our ability to institute a highly progressive tax system. The choice is ours. We can countenance a sprawling industry that helps the affluent dodge taxation, or we can choose to regulate it. We can let multinationals pick the country where they declare their profits, or we can pick for them. We can tolerate financial opacity and the countless possibilities for tax evasion that come with it, or we can choose to measure, record and tax wealth.

If we believe most commentators, tax avoidance is a law of nature. Because politics is messy and democracy imperfect, this argument goes, the tax code is always full of “loopholes” that the rich will exploit. Tax justice has never prevailed, and it will never prevail. […] But they are mistaken.

Science writer Ed Yong noticed that the stories he was writing quoted sources that were disproportionately male. Using a spreadsheet to track who he contacted for stories and a few extra minutes per piece, Yong set about changing that gender imbalance.

Skeptics might argue that I needn’t bother, as my work was just reflecting the present state of science. But I don’t buy that journalism should act simply as society’s mirror. Yes, it tells us about the world as it is, but it also pushes us toward a world that could be. It is about speaking truth to power, giving voice to the voiceless. And it is a profession that actively benefits from seeking out fresh perspectives and voices, instead of simply asking the same small cadre of well-trod names for their opinions.

Another popular critique is that I should simply focus on finding the most qualified people for any given story, regardless of gender. This point seems superficially sound, but falls apart at the gentlest scrutiny. How exactly does one judge “most qualified”? Am I to list all the scientists in a given field and arrange them by number of publications, awards, or h-index, and then work my way down the list in descending order? Am I to assume that these metrics somehow exist in a social vacuum and are not themselves also influenced by the very gender biases that I am trying to resist? It would be crushingly naïve to do so.

Journalism and science both work better with the inclusion and participation of a diverse set of voices bent on the pursuit of truth.

Update: NY Times’ columnist David Leonhardt conducted his own experiment and discovered I’m Not Quoting Enough Women.

In response to some poorly conducted and racist research attempting to correlate the size of people’s brains to their intelligence, science historian and paleontologist Stephen Jay Gould wrote in his 1980 book, The Panda’s Thumb:

I am, somehow, less interested in the weight and convolutions of Einstein’s brain than in the near certainty that people of equal talent have lived and died in cotton fields and sweatshops.

Gould’s assertion is echoed by this piece in the NY Times, in which David Leonhardt reports on the research of Stanford’s Raj Chetty. Chetty’s findings (unsurprisingly) show that financial inequality and differences in race & sex have a large effect on which Americans end up inventing things. Leonhardt calls this “a betrayal of American ideals”.

Not surprisingly, children who excelled in math were far more likely to become inventors. But being a math standout wasn’t enough. Only the top students who also came from high-income families had a decent chance to become an inventor.

This fact may be the starkest: Low-income students who are among the very best math students — those who score in the top 5 percent of all third graders — are no more likely to become inventors than below-average math students from affluent families.

In the article, AOL founder Steve Case says: “Creativity is broadly distributed. Opportunity is not.” The problem is even more severe when you consider differences in sex and race:

I encourage you to take a moment to absorb the size of these gaps. Women, African-Americans, Latinos, Southerners, and low- and middle-income children are far less likely to grow up to become patent holders and inventors. Our society appears to be missing out on most potential inventors from these groups. And these groups together make up most of the American population.

Because of survivorship bias, it’s tough to focus on the potential inventors, the lost Einsteins:

The key phrase in the research paper is “lost Einsteins.” It’s a reference to people who could “have had highly impactful innovations” if they had been able to pursue the opportunities they deserved, the authors write. Nobody knows precisely who the lost Einsteins are, of course, but there is little doubt that they exist.

Arizona Senator John McCain has publicly come out against the latest Republican attempt to repeal the ACA. His statement begins:

As I have repeatedly stressed, health care reform legislation ought to be the product of regular order in the Senate. Committees of jurisdiction should mark up legislation with input from all committee members, and send their bill to the floor for debate and amendment. That is the only way we might achieve bipartisan consensus on lasting reform, without which a policy that affects one-fifth of our economy and every single American family will be subject to reversal with every change of administration and congressional majority.

I would consider supporting legislation similar to that offered by my friends Senators Graham and Cassidy were it the product of extensive hearings, debate and amendment. But that has not been the case. Instead, the specter of September 30th budget reconciliation deadline has hung over this entire process.

Many opponents of the ACA repeal are hailing McCain as a hero for going against his party leadership on this issue. I don’t see it — he’d still support a bill like Graham-Cassidy that would take away healthcare coverage from millions of Americans if only it were the result of proper procedure — particularly because of what he says next (italics mine):

We should not be content to pass health care legislation on a party-line basis, as Democrats did when they rammed Obamacare through Congress in 2009.

This is false. The NY Times’ David Leonhardt explained back in March during another Republican repeal effort:

When Barack Obama ran for president, he faced a choice. He could continue moving the party to the center or tack back to the left. The second option would have focused on government programs, like expanding Medicare to start at age 55. But Obama and his team thought a plan that mixed government and markets — farther to the right of Clinton’s — could cover millions of people and had a realistic chance of passing.

They embarked on a bipartisan approach. They borrowed from Mitt Romney’s plan in Massachusetts, gave a big role to a bipartisan Senate working group, incorporated conservative ideas and won initial support from some Republicans. The bill also won over groups that had long blocked reform, like the American Medical Association.

But congressional Republicans ultimately decided that opposing any bill, regardless of its substance, was in their political interest. The consultant Frank Luntz wrote an influential memo in 2009 advising Republicans to talk positively about “reform” while also opposing actual solutions. McConnell, the Senate leader, persuaded his colleagues that they could make Obama look bad by denying him bipartisan cover.

Adam Jentleson, former Deputy Chief of Staff for Senator Harry Reid, said basically the same thing on Twitter:

The votes were party-line, but that was a front manufactured by McConnell. He bragged about it at the time. McConnell rarely gives much away but he let the mask slip here, saying he planned to oppose Obamacare regardless of what was in the bill. Those who worked on and covered the bill know there were GOP senators who wanted to support ACA — but McConnell twisted their arms. On Obamacare, Democrats spent months holding hearings and seeking GOP input — we accepted 200+ GOP amendments!

For reference, here was the Senate vote, straight down party lines. Hence the “ramming” charge…if you didn’t know any better. Luckily, Snopes does know better.

According to Mark Peterson, chair of the UCLA Department of Public Policy, one easy metric by which to judge transparency is the number of hearings held during the development of a bill, as well as the different voices heard during those hearings. So far, the GOP repeal efforts have been subject to zero public hearings.

In contrast, the ACA was debated in three House committees and two Senate committees, and subject to hours of bipartisan debate that allowed for the introduction of amendments. Peterson told us in an e-mail that he “can’t recall any major piece of legislation that was completely devoid of public forums of any kind, and that were crafted outside of the normal committee and subcommittee structure to this extent”.

The Wikipedia page about the ACA tells much the same story.

Stay Connected