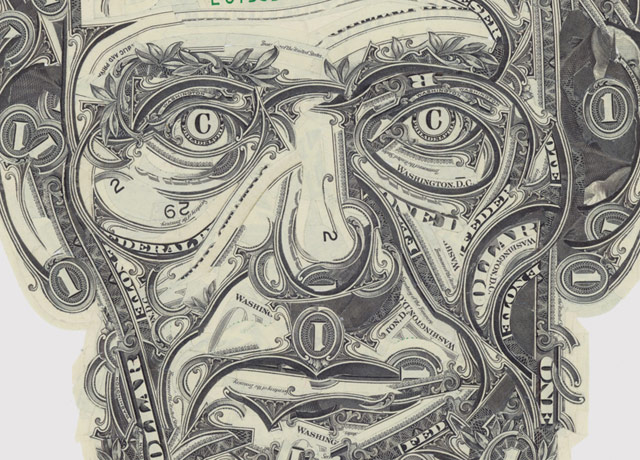

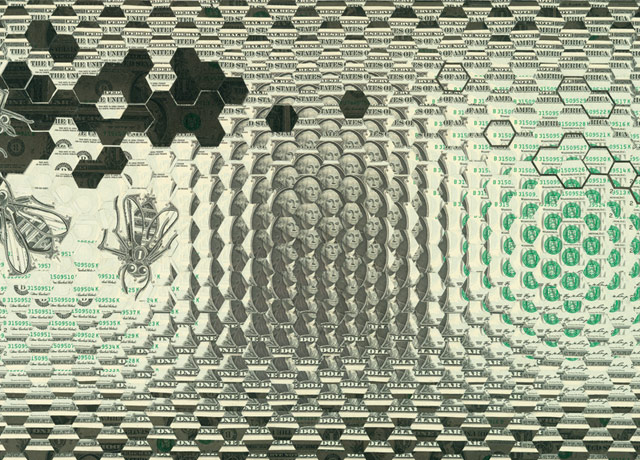

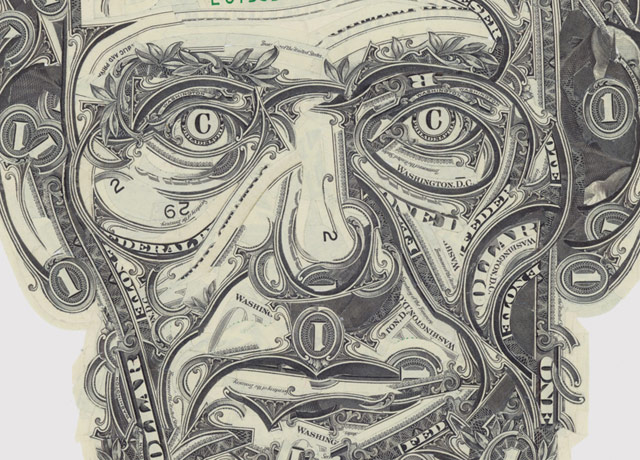

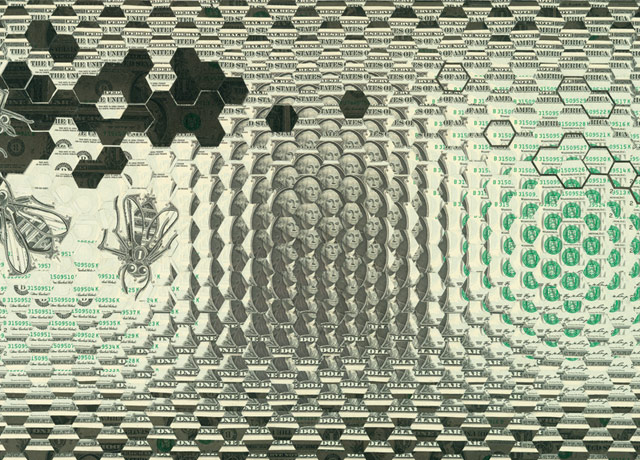

The art of currency

Mark Wagner constructs intricate works of collage out of pieces of US $1 bills.

I love that last one. No Photoshop…he cuts and assembles the pieces by hand:

This site is made possible by member support. 💞

Big thanks to Arcustech for hosting the site and offering amazing tech support.

When you buy through links on kottke.org, I may earn an affiliate commission. Thanks for supporting the site!

kottke.org. home of fine hypertext products since 1998.

Mark Wagner constructs intricate works of collage out of pieces of US $1 bills.

I love that last one. No Photoshop…he cuts and assembles the pieces by hand:

File this under “markets in everything”: people will pay big money for US currency notes with interesting serial numbers.

In addition to the “low numbers,” which stop at 100, there are “ladders,” which have numbers in sequence, such as 12345678 or 54321098. These sell for as much as $1,300. A “radar” (selling for $20 to $40) is a palindrome, such as 35299253, and “repeaters” are notes with two blocks of the same four digits, like 41884188. Undis observes subcategories of each of these, such as “super radars” ($75 to $100) that have all internal digits the same, like 46666664.

And here I thought I was being pretty eagle-eyed by fishing a $2 bill out of the tip jar at the bagel place this morning. (via digg)

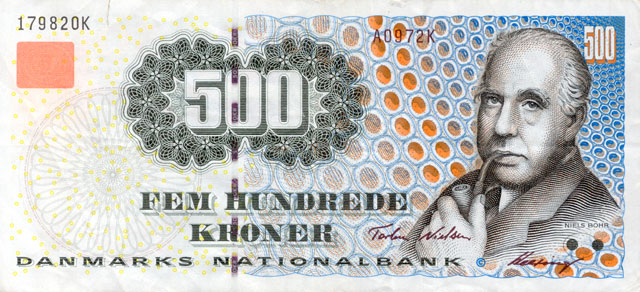

Some countries, the cool ones, put physicists and other scientists on their money. Here’s Niels Bohr on the Danish 500 kroner note:

Even the US sneaks onto the cool list with Ben Franklin on the $100.

US currency is already embarrassing and this new design for the $100 bill is not helping.

This may be worse than the horrible US passport.

For a project called The Fundamental Units, Martin John Callanan used a very powerful 3D microscope to take 400-megapixel images of the lowest denomination coin from each of the world’s 166 active currencies. This is the 1 stotinki coin from Bulgaria:

And this is a small part of that same coin at tremendous zoom:

From a site called Celebrity Net Worth (I know, blech), a list of the 25 richest people of all time, adjusted for inflation. Gates, Buffett, and Rockefeller all make the list but the big cheese is Malian emperor Mansa Musa I, with a net worth of $400 billion in today’s dollars.

Mansa Musa I of Mali is the richest human being in history with a personal net worth of $400 billion! Mansa Musa lived from 1280 - 1337 and ruled the Malian Empire which covered modern day Ghana, Timbuktu and Mali in West Africa. Mansa Musa’s shocking wealth came from his country’s vast production of more than half the world’s supply of salt and gold.

(via @DavidGrann)

In this week’s New Yorker, Chrystia Freeland writes about how the ultra-rich have taken a dislike to President Obama and his anti-business policy and rhetoric, even though the President “has served the rich quite well”. This article is infuriating, a bunch of very powerful men (and they are all men) sitting around crying about their powerlessness. A few choice quotes:

Cooperman regarded the comments as a declaration of class warfare, and began to criticize Obama publicly. In September, at a CNBC conference in New York, he compared Hitler’s rise to power with Obama’s ascent to the Presidency, citing disaffected majorities in both countries who elected inexperienced leaders.

Strong argument there. Per Godwin, that should have been the end of it.

Evident throughout the letter is a sense of victimization prevalent among so many of America’s wealthiest people. In an extreme version of this, the rich feel that they have become the new, vilified underclass.

Underclass! Boo hoo! Do you want some cheese with that 2005 Petrus?

T. J. Rodgers, a libertarian and a Silicon Valley entrepreneur, has taken to comparing Barack Obama’s treatment of the rich to the oppression of ethnic minorities — an approach, he says, that the President, as an African-American, should be particularly sensitive to.

Yes, I can imagine the President nodding, upset at missing the obvious parallel here. The police chasing hedge fund managers through the streets of lower Manhattan with firehoses is a scene that I will never forget.

[Founding partner of the hedge fund AQR Capital Management Clifford S. Asness] suggested that “hedge funds really need a community organizer,” and accused the White House of “bullying” the financial sector.

Clifford S. Asness swinging from the bathroom door knob by his underwear. Clifford S. Asness called “Assness” in trigonometry class. Nude photos taken of Clifford S. Asness in the locker room and distributed to the freshman girls. Clifford S. Asness teased so mercilessly about his acne that he has to stay home from school throwing up from the emotional pain of being so thoroughly and callously rejected by one’s peers.

In 2010, the private-equity billionaire Stephen Schwarzman, of the Blackstone Group, compared the President’s as yet unsuccessful effort to eliminate some of the preferential tax treatment his sector receives to Hitler’s invasion of Poland.

Hitler again! Obama is obviously a fascist communist.

“You know, the largest and greatest country in the free world put a forty-seven-year-old guy that never worked a day in his life and made him in charge of the free world,” Cooperman said. “Not totally different from taking Adolf Hitler in Germany and making him in charge of Germany because people were economically dissatisfied.

Hitler, take three. Stick with what you know.

He was a seventy-two-year-old world-renowned cardiologist; his wife was one of the country’s experts in women’s medicine. Together, they had a net worth of around ten million dollars. “It was shocking how tight he was going to be in retirement,” Cooperman said. “He needed four hundred thousand dollars a year to live on. He had a home in Florida, a home in New Jersey. He had certain habits he wanted to continue to pursue.

Shocking. Needed. Certain habits.

People don’t realize how wealthy people self-tax. If you have a certain cause, an art museum or a symphony, and you want to support it, it would be nice if you had the choice.

We didn’t realize that. And it’s such an either-or thing too…can’t pay your taxes *and* help the Met buy a Vermeer.

In 1985’s Brewster’s Millions, Richard Pryor played a man who stood to inherit $300 million if he could spend $30 million in a month without telling anyone why. Great movie. They should remake it. It’s not a perfect analogy, but billionaire Charles F. Feeney is trying to spend all of his money just the same. In 1982, he used $6 billion of his fortune to fund Atlantic Philanthropies. Feeney was able to run the foundation anonymously for 15 years by utilizing Bermuda’s flexible disclosure laws. This also meant he wasn’t able to deduct these donations from his taxes.

He’s raised his profile lately with the hope of inspiring other rich people to spend their money the same way, and Warren Buffett refers to him as the “spiritual leader” of the effort to encourage billionaires to pledge half their fortune to philanthropy.

When the last of its money has been spent and it closes its doors sometime around 2020, Atlantic Philanthropies will be by far the largest such organization to have voluntarily shut itself down, according to Steven Lawrence, director of research for the Foundation Center. (The much bigger Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation plans to shut down 50 years after its founders die.)

By its end, Atlantic will have invested about $7.5 billion in direct medical care, immigration reform, education, criminal justice advocacy and peace-building initiatives. It was an invisible hand at the end of armed conflicts in South Africa and in Northern Ireland, providing funds to buttress constitutional politics over paramilitary action. It has supported marriage-equality campaigns, death penalty opponents and contributed $25 million to push health care reform.

More like this please. (via @randomantonym)

Writing for IEEE Spectrum, New Yorker staff writer James Surowiecki writes about the development and evolution of money, from that of tribal societies to today’s highly abstracted currencies.

It’s really in the seventh century B.C.E., when the small kingdom of Lydia introduced the world’s first standardized metal coins, that you start to see money being used in a recognizable way. Located in what is now Turkey, Lydia sat on the cusp between the Mediterranean and the Near East, and commerce with foreign travelers was common. And that, it turns out, is just the kind of situation in which money is quite useful.

To understand why, imagine doing a trade in the absence of money-that is, through barter. (Let’s leave aside the fact that no society has ever relied solely or even largely on barter; it’s still an instructive concept.) The chief problem with barter is what economist William Stanley Jevons called the “double coincidence of wants.” Say you have a bunch of bananas and would like a pair of shoes; it’s not enough to find someone who has some shoes or someone who wants some bananas. To make the trade, you need to find someone who has shoes he’s willing to trade and wants bananas. That’s a tough task.

With a common currency, though, the task becomes easy: You just sell your bananas to someone in exchange for money, with which you then buy shoes from someone else. And if, as in Lydia, you have foreigners from whom you’d like to buy or to whom you’d like to sell, having a common medium of exchange is obviously valuable. That is, money is especially useful when dealing with people you don’t know and may never see again.

In this same vein, this reply on Reddit to “Where has all the money in the world gone?” is also worth a read.

The thing to remember is that all throughout, from the initial trade to this central-banking system, all of this money is debt. It is IOUs, except instead of being an IOU that says “Kancho_Ninja will give one bushel of apples to the bearer of this bond in October”, it says “Anyone in town will give you anything worth one bushel of apples in trade.”

The money is not an actual thing that you can eat or wear or build a house with, it’s an IOU that is redeemable anywhere, for anything, from anyone. It is a promise to pay equivalent value at some time in the future, except the holder of the money can call on anybody at all to fulfill that promise — they don’t have to go back to the original promiser.

Frontline is doing a four-hour show about the world financial crisis, which, according to many people featured on the program, is ongoing.

Since 2008, Wall Street and Washington have fought against the tide of the fiercest financial crisis since the Great Depression. What have they wrought? In a special four-hour investigation, FRONTLINE tells the inside story of the struggles to rescue and repair a shattered economy, exploring key decisions, missed opportunities, and the unprecedented and uneasy partnership between government leaders and titans of finance that affects the fortunes of millions of people around the world.

The program airs on April 24th.

Sara Blakely is one of the few women who has joined the Forbes Billionaires list without help from a spouse or an inheritance. She came up with the idea for Spanx and spent two years and $5000 developing it and the $1 billion company it would become.

Blakely, then 27, moved to Atlanta, set aside her entire $5,000 savings and spent the next two years meticulously planning the launch of her product while working nine to five at Danka. She spent seven nights straight at the Georgia Tech library researching every hosiery patent ever filed. She visited craft stores like Michaels to find the right fabrics. She sought out hosiery mills in the Yellow Pages and started cold calling, only to be told no repeatedly. Immune to rejection thanks to years selling door-to-door, she decided just to show up. At the Acme-McCrary hosiery factory in Asheboro, N.C., she was turned away, only to receive a call from the manager two weeks later. He had daughters, he told her, who wouldn’t let him pass up her invention.

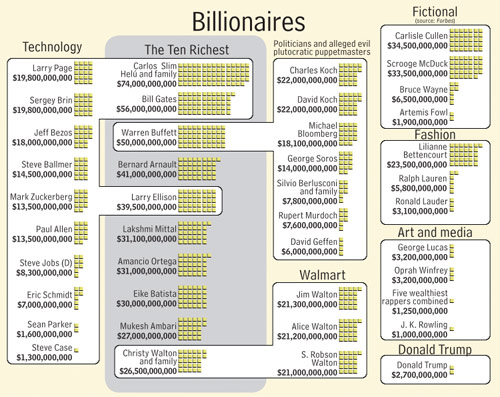

An epic chart from XKCD: Money - A chart of almost all of it, where it is, and what it can do. It’s broken out into “dollars, thousands, millions, billions, trillions”…here’s just a little snippet of the billions section:

James Somers noticed that his equity derivative-trading roommate was the only one of his young professional friends who comes home from work “buoyant and satisfied”, so he accompanied him to work one day to see what his job entailed. Turns out he basically plays video games all day.

A trader’s job is to be smarter than the market. He converts a mess of analysis and intuition into simple bets. He makes moves. If his predictions are better than everyone else’s, he wins money; if not, he loses it. At every moment he has a crystalline picture of his bottom line, the “P and L” (profit and loss) that determines how much of a bonus he’ll get and, more importantly, where he stands among his peers. As my friend put it, traders are “very, very, very competitive.” At the end of the day they ask each other “how did you do today?” Trading is one of the few jobs with an actual leaderboard, which, if you’ve ever been on one, or strived to get there, you’ll recognize as being perhaps the single most powerful driver of a gamer’s engagement.

That seems to be the core of it, but no doubt there are other game-like features in play here: the importance of timing and tactile dexterity; the clear presence of two abstract levels of attention and activity, one long-term and strategic, the other fiercely tactical, localized in bursts a minute or two long; the need for teams and ceaseless chatter; and so on.

Athleticism and competitiveness are often downplayed when we talk about white collar careers but are essential in many disciplines. Doctors (surgeons in particular) have both those traits, founding a startup company is definitely competitive and can be as physically demanding as running, teachers are standing or walking all day long, and even something like programming requires manual dexterity with the mouse & keyboard and the stamina to sit in a chair paying single-minded attention to a task for 10-12 hours a day. (via @tcarmody)

From the New Yorker a week or two ago, John Cassidy has an article about the social value of what Wall Street and investment banking. It’s not a pretty picture.

Lord Adair Turner, the chairman of Britain’s top financial watchdog, the Financial Services Authority, has described much of what happens on Wall Street and in other financial centers as “socially useless activity” — a comment that suggests it could be eliminated without doing any damage to the economy. In a recent article titled “What Do Banks Do?,” which appeared in a collection of essays devoted to the future of finance, Turner pointed out that although certain financial activities were genuinely valuable, others generated revenues and profits without delivering anything of real worth — payments that economists refer to as rents. “It is possible for financial activity to extract rents from the real economy rather than to deliver economic value,” Turner wrote. “Financial innovation…may in some ways and under some circumstances foster economic value creation, but that needs to be illustrated at the level of specific effects: it cannot be asserted a priori.”

Turner’s viewpoint caused consternation in the City of London, the world’s largest financial market. A clear implication of his argument is that many people in the City and on Wall Street are the financial equivalent of slumlords or toll collectors in pin-striped suits. If they retired to their beach houses en masse, the rest of the economy would be fine, or perhaps even healthier.

I particularly enjoyed the characterization of banking as a utility:

Most people on Wall Street, not surprisingly, believe that they earn their keep, but at least one influential financier vehemently disagrees: Paul Woolley, a seventy-one-year-old Englishman who has set up an institute at the London School of Economics called the Woolley Centre for the Study of Capital Market Dysfunctionality. “Why on earth should finance be the biggest and most highly paid industry when it’s just a utility, like sewage or gas?” Woolley said to me when I met with him in London. “It is like a cancer that is growing to infinite size, until it takes over the entire body.”

p.s. Thanks to Typekit, the New Yorker’s web site now uses the same familiar typefaces that you find in the magazine. Looks great.

Man, that guy really hates pennies, aka “disgusting bacteria-ridden disks of suck that fail to facilitate commerce”.

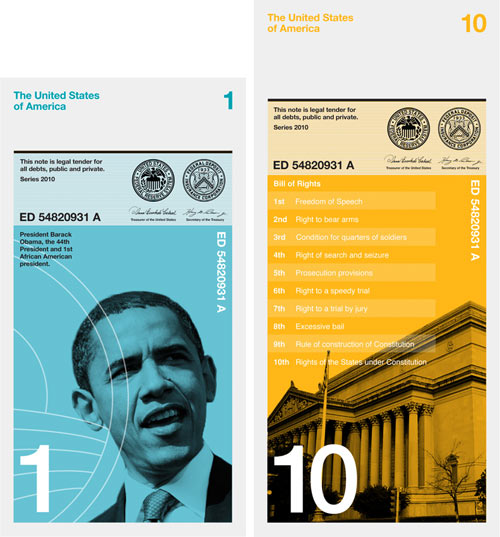

A very nice US currency redesign by Dowling Duncan.

When we researched how notes are used we realized people tend to handle and deal with money vertically rather than horizontally. You tend to hold a wallet or purse vertically when searching for notes. The majority of people hand over notes vertically when making purchases. All machines accept notes vertically. Therefore a vertical note makes more sense.

The note imagery relates to the value of each note:

$1 - The first African American president

$5 - The five biggest native American tribes

$10 - The bill of rights, the first 10 amendments to the US Constitution

$20 - 20th Century America

$50 - The 50 States of America

$100 - The first 100 days of President Franklin Roosevelt.

Needs more guilloche but other than that: fire up the presses.

David Graeber has been researching the history of money and debt for a book he’s writing. This abbreviated version of his findings makes for really interesting reading.

However tawdry their origins, the creation of new media of exchange — coinage appeared almost simultaneously in Greece, India, and China — appears to have had profound intellectual effects. Some have even gone so far as to argue that Greek philosophy was itself made possible by conceptual innovations introduced by coinage. The most remarkable pattern, though, is the emergence, in almost the exact times and places where one also sees the early spread of coinage, of what were to become modern world religions: prophetic Judaism, Christianity, Buddhism, Jainism, Confucianism, Taoism, and eventually, Islam. While the precise links are yet to be fully explored, in certain ways, these religions appear to have arisen in direct reaction to the logic of the market. To put the matter somewhat crudely: if one relegates a certain social space simply to the selfish acquisition of material things, it is almost inevitable that soon someone else will come to set aside another domain in which to preach that, from the perspective of ultimate values, material things are unimportant, and selfishness — or even the self — illusory.

There are at least 2 crazy passages in this article about the amount of inflation in Zimbabwe over the past 30 years.

Hyperinflation in Zimbabwe, the former Rhodesia, was a quadrillion times worse than it was in Weimar Germany.

In grade school, quadrillion was always an exaggeration but not here:

The cumulative devaluation of the Zimbabwe dollar was such that a stack of 100,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 (26 zeros) two dollar bills (if they were printed) in the peak hyperinflation would have be needed to equal in value what a single original Zimbabwe two-dollar bill of 1978 had been worth. Such a pile of bills literally would be light years high, stretching from the Earth to the Andromeda Galaxy.

Andromeda Galaxy! It’s our nearest galactic neighbor but still 2,500,000 light-years away. (via daveg)

Who knew that a long article about F Scott Fitzgerald’s tax returns could be so interesting?

The five months of furious short-story writing in 1923-24 had left him with a stake of $7,000. In Great Neck, that would only cover two and a half months of expenses. How could he stretch the $7,000 to gain the time to finish Gatsby? Earlier, as he was struggling to save, a friend wrote from France to suggest that Fitz-gerald join the many Americans living well in Europe on the strong American dollar. The friend wrote that it cost one-tenth as much to live in Europe: he had just finished “a meal fit for a king, washed down with champagne, for the absurd sum of sixty-one cents.” Fitzgerald thought, based on the friend’s recommendation, living expenses on the off-season Riviera would be low enough to let him finish Gatsby without any short-story interruptions.

This American Life recently aired a follow-up to their well-received program about the recent financial crisis called Return To The Giant Pool of Money.

We catch back up with the people we met in 2008, to see how they’ve fared over the last 18 months. We talk to Clarence Nathan, who in 2008 received a half million dollar loan that he said he wouldn’t have given himself; Jim Finkel, a Wall Street finance guy, who put together and managed complicated mortgage-based financial securities; Richard Campbell, the Marine who was facing foreclosure; and Glen Pizzolorusso, the mortgage company sales manager who led the life of a b-list celebrity.

On Reddit, an informal Q&A with a $30 million lottery winner about how the money has changed his life.

I went to the lottery’s website after finding the ticket and realized that I had won. I freaked out ran up to my apartment’s door and locked all the locks. It was completely irrational.

(via cyn-c)

Daniel Suelo, who lives in a cave near Moab, Utah, has gone without using money since 2000.

“When I lived with money, I was always lacking,” he writes. “Money represents lack. Money represents things in the past (debt) and things in the future (credit), but money never represents what is present.”

The idea started to take shape when Suelo was on a Peace Corps mission to Ecuador. As he monitored the health of the population of the village he was staying in, he noticed that their health declined as they made more money — “It looked like money was impoverishing them.” You can find out more about Suelo’s philosophy on his web site and follow his adventures on his blog, both of which he updates at the public library.

New Scientist has collected a bunch of studies related to the pychological impact of money on people.

Almost all of us, for example, are “loss averse” — it hurts more to lose £50 than it feels good to win £50. We also value money in relative rather than absolute terms — we consider £10 irrelevant when buying a house but not when paying for a meal. Similarly, finding £100 will give many people more pleasure than having a heating bill cut from £950 to £835, even though this gains them more in real terms.

Michael Lewis, who is seemingly cranking out 10,000 words a day about finance and sports these days, writes in the pages of Vanity Fair about the Icelandic financial collapse. It’s an amazing story.

That was the biggest American financial lesson the Icelanders took to heart: the importance of buying as many assets as possible with borrowed money, as asset prices only rose. By 2007, Icelanders owned roughly 50 times more foreign assets than they had in 2002. They bought private jets and third homes in London and Copenhagen. They paid vast sums of money for services no one in Iceland had theretofore ever imagined wanting. “A guy had a birthday party, and he flew in Elton John for a million dollars to sing two songs,” the head of the Left-Green Movement, Steingrimur Sigfusson, tells me with fresh incredulity. “And apparently not very well.” They bought stakes in businesses they knew nothing about and told the people running them what to do — just like real American investment bankers!

But it was all essentially make-believe.

A handful of guys in Iceland, who had no experience of finance, were taking out tens of billions of dollars in short-term loans from abroad. They were then re-lending this money to themselves and their friends to buy assets — the banks, soccer teams, etc. Since the entire world’s assets were rising — thanks in part to people like these Icelandic lunatics paying crazy prices for them — they appeared to be making money. Yet another hedge-fund manager explained Icelandic banking to me this way: You have a dog, and I have a cat. We agree that they are each worth a billion dollars. You sell me the dog for a billion, and I sell you the cat for a billion. Now we are no longer pet owners, but Icelandic banks, with a billion dollars in new assets. “They created fake capital by trading assets amongst themselves at inflated values,” says a London hedge-fund manager. “This was how the banks and investment companies grew and grew. But they were lightweights in the international markets.”

In Germany in the 1920s, towns, banks, and companies printed their own money called notgeld.

Notgeld was mainly issued in the form of (paper) banknotes. Sometimes other forms were used, as well: coins, leather, silk, linen, stamps, aluminium foil, coal, and porcelain; there are also reports of elemental sulfur being used, as well as all sorts of re-used paper and carton material.

A Flickr user has uploaded hundreds of examples of the notgeld notes collected by his wife’s family; they’re so colorful! (via design observer)

The story is a bit out-of-date, but this overview of the cause and effects of the Icelandic financial crisis is still worth a read.

Picture a pig trying to balance on a mouse’s back and you’ll get some idea of the scale of the problem. In a mere seven years since bank deregulation and privatisation, Iceland’s financial institutions had managed to rack up $75bn of foreign debt. In his address to the nation, Haarde put the problem in perspective by referring to the $700bn financial rescue package in America: “The huge measures introduced by the US authorities to rescue their banking system represent just under 5 per cent of the US GDP. The total economic debt of the Icelandic banks, however, is many times the GDP of Iceland.”

Michael Lewis takes a look at the current financial crisis and traces its roots back to the 1980s and the events chronicled in his book, Liar’s Poker. He begins by introducing us to some analysts and investors that saw the whole thing coming. One of those people is Steve Eisman.

“We have a simple thesis,” Eisman explained. “There is going to be a calamity, and whenever there is a calamity, Merrill is there.” When it came time to bankrupt Orange County with bad advice, Merrill was there. When the internet went bust, Merrill was there. Way back in the 1980s, when the first bond trader was let off his leash and lost hundreds of millions of dollars, Merrill was there to take the hit. That was Eisman’s logic-the logic of Wall Street’s pecking order. Goldman Sachs was the big kid who ran the games in this neighborhood. Merrill Lynch was the little fat kid assigned the least pleasant roles, just happy to be a part of things. The game, as Eisman saw it, was Crack the Whip. He assumed Merrill Lynch had taken its assigned place at the end of the chain.

It’s a fantastic article, well worth reading to the end…the final dozen paragraphs are the best part of the whole thing. Who knew deviled eggs were so pregnant with metaphor?

As I was reading the article, Matt Bucher dropped a note into my inbox. As hoped for months ago, Lewis is writing a book about this whole mess.

MONEYBALL and THE BLIND SIDE author Michael Lewis’s untitled behind-the-scenes story of a few men and women who foresaw the current economic disaster, tried to prevent it, but were overruled by the financial institutions with whom they worked, sold to Star Lawrence at Norton, by Al Zuckerman at Writers House (NA).

The Portfolio piece will definitely find itself into the book, as will this piece on Meredith Whitney, this one on Goldman Sachs, Lewis’ subprime parable, and other pieces from Bloomberg, Porfolio, and his upcoming gig at Vanity Fair. One question though…what happens to Lewis’ forthcoming book on New Orleans? Did that just disappear?

On the one hand, lack of slack tells us the poor must make higher quality decisions because they don’t have slack to help buffer them with things. But even though they have to supply higher quality decisions, they’re in a worse position to supply them because they’re depleted. That is the ultimate irony of poverty. You’re getting cut twice. You are in an environment where the decisions have to be better, but you’re in an environment that by the very nature of that makes it harder for you apply better decisions.

This radio program made the rounds last week, but I finally got caught up this weekend so I’ll add my voice to the chorus urging you to listen to This American Life’s episode on the financial crisis, Another Frightening Show About the Economy. Paired with The Giant Pool of Money from back in May, this is an excellent overview of what’s going on in the financial markets right now. The hosts of the two shows are also doing a daily blog/podcast thing at Planet Money In addition, the last half of this week’s TAL concerns the political angle of the financial mess. I haven’t had a chance to listen yet, but check it out if you’re into that sort of thing.

Stay Connected