kottke.org posts about finance

The story is a bit out-of-date, but this overview of the cause and effects of the Icelandic financial crisis is still worth a read.

Picture a pig trying to balance on a mouse’s back and you’ll get some idea of the scale of the problem. In a mere seven years since bank deregulation and privatisation, Iceland’s financial institutions had managed to rack up $75bn of foreign debt. In his address to the nation, Haarde put the problem in perspective by referring to the $700bn financial rescue package in America: “The huge measures introduced by the US authorities to rescue their banking system represent just under 5 per cent of the US GDP. The total economic debt of the Icelandic banks, however, is many times the GDP of Iceland.”

Michael Lewis takes a look at the current financial crisis and traces its roots back to the 1980s and the events chronicled in his book, Liar’s Poker. He begins by introducing us to some analysts and investors that saw the whole thing coming. One of those people is Steve Eisman.

“We have a simple thesis,” Eisman explained. “There is going to be a calamity, and whenever there is a calamity, Merrill is there.” When it came time to bankrupt Orange County with bad advice, Merrill was there. When the internet went bust, Merrill was there. Way back in the 1980s, when the first bond trader was let off his leash and lost hundreds of millions of dollars, Merrill was there to take the hit. That was Eisman’s logic-the logic of Wall Street’s pecking order. Goldman Sachs was the big kid who ran the games in this neighborhood. Merrill Lynch was the little fat kid assigned the least pleasant roles, just happy to be a part of things. The game, as Eisman saw it, was Crack the Whip. He assumed Merrill Lynch had taken its assigned place at the end of the chain.

It’s a fantastic article, well worth reading to the end…the final dozen paragraphs are the best part of the whole thing. Who knew deviled eggs were so pregnant with metaphor?

As I was reading the article, Matt Bucher dropped a note into my inbox. As hoped for months ago, Lewis is writing a book about this whole mess.

MONEYBALL and THE BLIND SIDE author Michael Lewis’s untitled behind-the-scenes story of a few men and women who foresaw the current economic disaster, tried to prevent it, but were overruled by the financial institutions with whom they worked, sold to Star Lawrence at Norton, by Al Zuckerman at Writers House (NA).

The Portfolio piece will definitely find itself into the book, as will this piece on Meredith Whitney, this one on Goldman Sachs, Lewis’ subprime parable, and other pieces from Bloomberg, Porfolio, and his upcoming gig at Vanity Fair. One question though…what happens to Lewis’ forthcoming book on New Orleans? Did that just disappear?

Jonah Lehrer answers the burning question of the day: what do cod fish have to do with the current financial crisis?

The [cod population] models were all wrong. The cod population never grew. By the late 1980’s, even the trawlers couldn’t find cod. It was now clear that the scientists had made some grievous errors. The fishermen hadn’t been catching 16 percent of the cod population; they had been catching 60 percent of the cod population. The models were off by a factor of four. “For the cod fishery,” write Orrin Pilkey and Linda Pilkey-Jarvis, in their excellent book Useless Arithmetic: Why Environmental Scientists Can’t Predict the Future, “as for most of earth’s surface systems, whether biological or geological, the complex interaction of huge numbers of parameters make mathematical modeling on a scale of predictive accuracy that would be useful to fishers a virtual impossibility.”

In the same way, incorrect but highly lucrative financial models caused people to take on too much risk and leverage.

Volkswagen was briefly the world’s largest company in terms of market cap today.

Volkswagen briefly became the world’s largest company by market capitalisation on Tuesday as panic-buying by hedge funds desperate to cover losses caused its value to shoot up by up to €150bn.

Porsche revealed that it owned 74% of VW instead of the previously assumed 35%…which caused panicked buying by hedge funds. (via mr)

James Surowiecki, who writes the biweekly financial column for the New Yorker, has started a finance blog on the NYer site called The Balance Sheet.

This radio program made the rounds last week, but I finally got caught up this weekend so I’ll add my voice to the chorus urging you to listen to This American Life’s episode on the financial crisis, Another Frightening Show About the Economy. Paired with The Giant Pool of Money from back in May, this is an excellent overview of what’s going on in the financial markets right now. The hosts of the two shows are also doing a daily blog/podcast thing at Planet Money In addition, the last half of this week’s TAL concerns the political angle of the financial mess. I haven’t had a chance to listen yet, but check it out if you’re into that sort of thing.

Phil Gyford, wearing his finest pair of Tufte trousers, takes a chart of the FTSE that the Guardian ran on Saturday and places it on a scale that shows the fluctuations of Friday’s market compared to the full value of the index.

This particular annoyance is the graphs of share prices in the press and on TV. It is standard practice to start the y-axis at a number much higher than zero, in order to magnify the ups and downs of the market.

This is perhaps the most succinct explanation of the current financial crisis I had read: The Financial Crisis, as Explained to My Fourteen-Year-Old Sister.

Kevin: Imagine that I let you borrow $50, but in exchange for my generosity, you promise to pay me back the $50 with an extra $10 in interest. To make sure you pay me back, I take your Charizard Pokémon card as collateral.

Olivia: Kevin, I don’t play Pokémon anymore.

Kevin: I’m getting to that. Let’s say that the Charizard is worth $50, so in case you decide to not return my money, at least I’ll have something that’s worth what I loaned out.

Olivia: Okay.

Kevin: But one day, people realize that Pokémon is stupid and everyone decides that the cards are overvalued. That’s right — everybody turned twelve on the same day! Now your Charizard is only worth, say, $25.

The only thing that’s missing is the part of the explanation where the parents swoop in and pay Kevin full value for that Pokémon card, which allows him to keep lending money in exchange for cardboard rectangles.

The Money Meltdown is a one-page site which aims to provide visitors with the best places to go online to get a handle on the current financial crisis. (thx, robin)

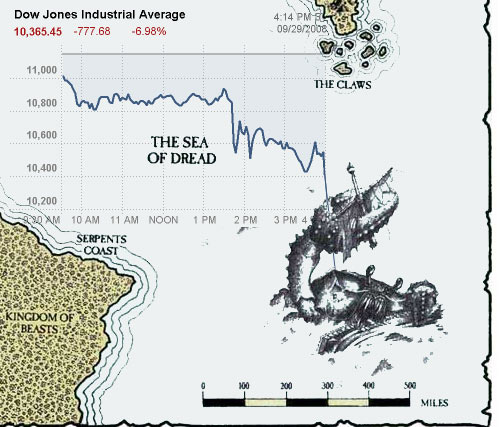

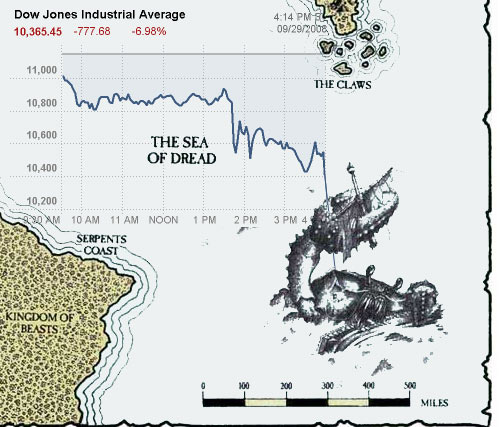

While following the market yesterday, I updated my Twitter account after a particularly precipitous mid-afternoon drop in the DJIA:

The DJIA trend line just kinda disappeared off the bottom of the chart there into Here Be Monsters territory about 30 minutes ago.

I meant “here be dragons” but you get the idea. Anyway, a reader sent in this chart that captures what many were feeling after the market closed.

The Sea of Dread, indeed. (thx, margaret)

High-end prostitutes see an uptick in business — for a few months anyway — during times of financial hardship and crisis.

Their clients were coming to them for a mix of escape and encouragement. As Jean, a New Yorker and a 35-year-old former paralegal turned “corporate escort” (her description) told me, “I had about two dozen men who started doubling their visits with me. They couldn’t face their wives, who were bitching about the fact they lost income. Men want to be men. All I did was make them feel like they could go back out there with their head up.”

Indeed, forty percent of encounters between high-end prostitutes don’t involve sex…like therapy with occasional benefits.

Michael Lewis rents a mansion in New Orleans and finds in the experience a parable about the thirst of Americans for better housing than they can afford, the subprime mortgage crisis, and the ensuing financial panic.

The real moral is that when a middle-class couple buys a house they can’t afford, defaults on their mortgage, and then sits down to explain it to a reporter from the New York Times, they can be confident that he will overlook the reason for their financial distress: the peculiar willingness of Americans to risk it all for a house above their station. People who buy something they cannot afford usually hear a little voice warning them away or prodding them to feel guilty. But when the item in question is a house, all the signals in American life conspire to drown out the little voice. The tax code tells people like the Garcias that while their interest payments are now gargantuan relative to their income, they’re deductible. Their friends tell them how impressed they are-and they mean it. Their family tells them that while theirs is indeed a big house, they have worked hard, and Americans who work hard deserve to own a dream house. Their kids love them for it.

(thx, kabir)

Ok, Michael Lewis *is* writing a book about the current financial situation. Sort of. It’s called Panic: The Story of Modern Financial Insanity.

When it comes to markets, the first deadly sin is greed. Michael Lewis is our jungle guide through five of the most violent and costly upheavals in recent financial history: the crash of ‘87, the Russian default (and the subsequent collapse of Long-Term Capital Management), the Asian currency crisis of 1999, the Internet bubble, and the current sub-prime mortgage disaster.

It’s out in December so I imagine that it won’t include the current Lehman/AIG/Merrill/bailout kerfuffle, but that’s what “with new material” paperbacks are for. (thx, paul)

Michael Lewis looks on the bright side of the current financial crisis and finds five positive aspects.

Our willingness to believe that we can hire some expert to tell us how to outperform markets is a big problem, with big consequences. It underpins Wall Street’s brokerage operations, for instance, and leads to a lot more people giving out financial advice than should be giving out financial advice. Thanks to the current panic many Americans have learned that the experts who advise them what to do with their savings are, at best, fools.

God I hope he writes a book about all this someday, sort of a Liar’s Poker 2. He can call it Fool’s Roulette or something.

Google is providing real-time stock prices now…no page refresh necessary. So you can, for instance, watch Apple’s stock price drop after Jobs’ keynote. Now I know how daytraders feel…I can’t take my eyes off of the screen.

Yay! Today is sub-prime mortgage day on kottke.org, I guess. The collapse of the sub-prime mortgage market took everyone on Wall Street by surprise…except Goldman Sachs, which earned $11.6 billion in 2007 when everyone else lost money. How’d they do it? Michael Lewis says that Goldman went against the flow in shorting sub-prime mortgages by assuming that the entire rest of the industry, including their own expert and extremely well-paid traders, were, as Lewis puts it, “a bunch of idiots”.

Update: Here’s the WSJ article mentioned by Lewis in the above piece. (thx, andy)

n+1 magazine has a fascinating Interview with a Hedge Fund Manager. Topics of conversation include the sub-prime mortgage crisis. I gotta admit that I didn’t understand some of this, but most of it was pretty interesting. (via snarkmarket)

Hedge fund manager John Paulson and investor Jeff Greene both became insanely wealthy over the subprime mortgage crisis. But how? (Parsing the Wall Street Journal is hard!) So Paulson “had to think up a technical way to bet against the housing and mortgage markets.” His guys bought up “collateralized debt obligation” slices, which are repackaged mortgage securities. (Kind of lost already!) His firm also bought up “credit-default swaps.” Paulson then opened a hedge fund shop, taking $150-million in mostly European money to back his scheme. Then he hung on. Now “he tells investors ‘it’s still not too late’ to bet on economic troubles.” Neat! Paulson’s ex-friend Greene did much the same thing, getting an investment bank’s participation for assets for the swap. Then… something happened and he bought three jets and a 145-foot yacht. Finance for idiots explanations eagerly sought! (And is there any small-scale way to do such things? Or do the abilities of regular people to make money on a crisis stop at short-selling and investing in Halliburton?)

Michael Lewis on a new way in which insurance companies are evaluating risk with respect to natural catastrophes.

The logic of catastrophe is very different: either no one is affected or vast numbers of people are. After an earthquake flattens Tokyo, a Japanese earthquake insurer is in deep trouble: millions of customers file claims. If there were a great number of rich cities scattered across the planet that might plausibly be destroyed by an earthquake, the insurer could spread its exposure to the losses by selling earthquake insurance to all of them. The losses it suffered in Tokyo would be offset by the gains it made from the cities not destroyed by an earthquake. But the financial risk from earthquakes — and hurricanes — is highly concentrated in a few places. There were insurance problems that were beyond the insurance industry’s means. Yet insurers continued to cover them, sometimes unenthusiastically, sometimes recklessly.

James Simons, hedge fund manager, earned $1.7 billion last year. $1.7 fucking billion! His company charges fees of 5% of assets and 44% of profits while the fund grossed 84% this year. Can one person add $1.7 billion of value to the economy? Something is wrong here.

A record-breaking year for Goldman Sachs; they’re setting aside $16.5 billion for salaries, benefits, and bonuses. That’s $622,000 (!!!!!!) for each employee. Instead of the typical business puff piece telling us about what these i-bankers are going to do with their money (cars, houses, expensive dinners!), how about investigating where all this money is coming from and what, exactly, Goldman does that’s so beneficial to the economy to earn such incredible profits.

You know those spams you get touting penny stocks? It turns out they actually work. “The team found that a spammer who bought shares the day before starting an e-mail campaign and then sold them the day after could make a return on his or her investment of 4.9%. If he or she were to be a particularly effective spammer, returns to this strategy would be roughly 6%.”

Update: NPR report on the spam stocks study. (thx, jeff)

Daniel Gross on why the financial markets reacted to the London bombings as they did. Stocks dropped (but not too much), oil fell sharply, and transportation and insurance stocks took a bigger hit than most.

The Neiman Marcus Paradox: How dumb rich people end up in debt. “14 percent of people with more than $5 million in assets have credit-card balances [which is] mystifying since credit-card cash is perhaps the most expensive form of money legally available.”

Newer posts

Stay Connected