Borges on Homer, Milton, and Blindness

My favorite Jorge Luis Borges short story, “El Hacedor (The Maker),” is about the Greek poet Homer going blind:

He had never dwelled on memory’s delights. Impressions slid over him, vivid but ephemeral. A potter’s vermilion; the heavens laden with stars that were also gods; the moon, from which a lion had fallen; the slick feel of marble beneath slow sensitive fingertips; the taste of wild boar meat, eagerly torn by his white teeth; a Phoenician word; the black shadow a lance casts on yellow sand; the nearness of the sea or of a woman; a heavy wine, its roughness cut by honey-these could fill his soul completely. He knew what terror was, but he also knew anger and rage, and once he had been the first to scale an enemy wall. Eager, curious, casual, with no other law than fulfillment and the immediate indifference that ensues, he walked the varied earth and saw, on one seashore or another, the cities of men and their palaces. In crowded marketplaces or at the foot of a mountain whose uncertain peak might be inhabited by satyrs, he had listened to complicated tales which he accepted, as he accepted reality, without asking whether they were true or false.

Gradually now the beautiful universe was slipping away from him. A stubborn mist erased the outline of his hand, the night was no longer peopled by stars, the earth beneath his feet was unsure. Everything was growing distant and blurred. When he knew he was going blind he cried out; stoic modesty had not yet been invented and Hector could flee with impunity. I will not see again, he felt, either the sky filled with mythical dread, or this face that the years will transform. Over this desperation of his flesh passed days and nights. But one morning he awoke; he looked, no longer alarmed, at the dim things that surrounded him; and inexplicably he sensed, as one recognizes a tune or a voice, that now it was over and he had faced it, with fear but also with joy, hope, and curiosity. Then he descended into his memory, which seemed to him endless, and up from that vertigo he succeeded in bringing forth a forgotten recollection that shone like a coin under the rain, perhaps because he had never looked at it, unless in a dream.

Borges also gradually went blind, as had many members of his family. “The world of the blind is not the night that people imagine,” he said in a 1977 lecture called “Blindness,” collected in his magnificent posthumous anthology Selected Nonfictions. “I should say that I am speaking for myself, and for my father and my grandmother, who both died blind—blind, laughing, and brave, as I also hope to die. They inherited many things—blindness, for example—but one does not inherit courage.”

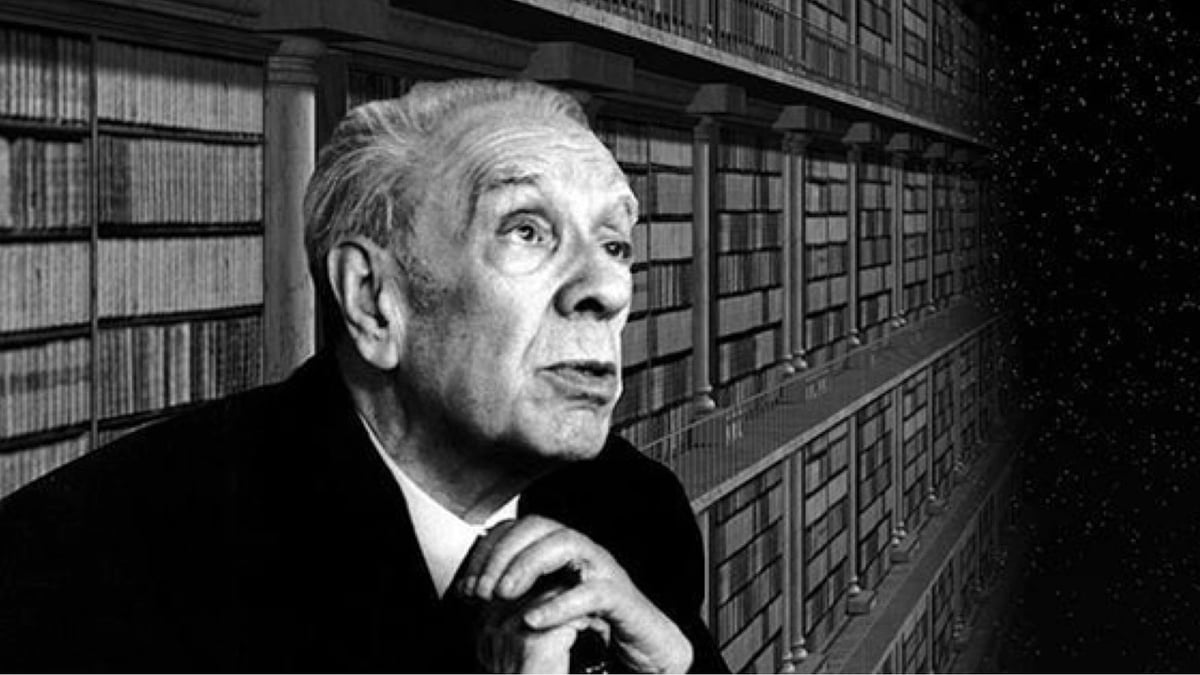

This lecture is the source of a famous Borges quote: “I had always imagined Paradise as a kind of library.” It does not usually include the context: Borges had been appointed as director of Argentina’s national library almost exactly when he became so blind he could no longer read.

No one should read self-pity or reproach

into this statement of the majesty of God;

who with such splendid irony

granted me books and blindness at one touch.

In his lecture, Borges discusses his own blindness, as well as that of Homer, Joyce, his predecessor at the library Paul Groussac, and a number of other writers. One of its most striking passages concerns John Milton, about whom Borges writes relatively little elsewhere. Milton, we’re told, went blind voluntarily, writing pamphlets in poor lighting to support the execution of Charles I, which landed him in political trouble after the Restoration. Borges likewise resisted, and survived Peron’s rule in Argentina.

Borges is especially struck by Milton’s Samson Agonistes, which is also about a blind hero who strikes down a wicked king.

He wanted to create a Greek tragedy. The action takes place in a single day, Samson’s last. Milton thought on the similarity of destinies, since he, like Samson, had been a strong man who was ultimately defeated. He was blind. And he wrote those verses which, according to Landor, he punctuated badly, but which in fact had to be “Eyeless, in Gaza, at the mill, with the slaves” — as if the misfortunes were accumulating on Samson.

Milton has a sonnet in which he speaks of his blindness. There is a line one can tell was written by a blind man. When he has to describe the world, he says, “In this dark world and wide.” It is precisely the world of the blind when they are alone, walking with hands outstretched, searching for props. Here we have an example — much more important than mine — of a man who overcomes blindness and does his work: Paradise Lost, Paradise Regained, Samson Agonistes, his best sonnets, part of A History of England, from the beginnings to the Norman Conquest. All of this was executed while he was blind; all of it had to be dictated to casual visitors.

Here we return to Borges’s “The Maker”:

Why did those memories come back to him, and why did they come without bitterness, as a mere foreshadowing of the present?

In grave amazement he understood. In this night too, in this night of his mortal eyes into this he was now descending, love and danger were again waiting. Ares and Aphrodite, for already he divined (already it encircled him) a murmur of glory and hexameters, a murmur of men defending a temple the gods will not save, and of black vessels searching the sea for a beloved isle, the murmur of the Odysseys and Iliads it was his destiny to sing and leave echoing concavely in the memory of man. These things we know, but not those that he felt when he descended into the last shade of all.

Stay Connected