The NY Times’ Randy Cohen is making

The NY Times’ Randy Cohen is making a literary map of Manhattan. Not a map of where authors hung out, but where their characters did.

This site is made possible by member support. ❤️

Big thanks to Arcustech for hosting the site and offering amazing tech support.

When you buy through links on kottke.org, I may earn an affiliate commission. Thanks for supporting the site!

kottke.org. home of fine hypertext products since 1998.

The NY Times’ Randy Cohen is making a literary map of Manhattan. Not a map of where authors hung out, but where their characters did.

Steven Johnson: “Imagine an alternate world identical to ours save one techno-historical change: videogames were invented and popularized before books”. “Reading books chronically under-stimulates the senses. Unlike the longstanding tradition of gameplaying — which engages the child in a vivid, three-dimensional world filled with moving images and musical soundscapes, navigated and controlled with complex muscular movements — books are simply a barren string of words on the page.”

Books that changed the world. Just a few of the things that have changed the world so far: cod, salt, chips, radio in Canada, sewing machines, atomic weaponry, quinine, cables, sheep, gunpower, etc. etc.

This biography of electricity — and of the men and women who had a hand in uncovering its inner workings — begins in the first moments after the Big Bang. Which is probably not where your high school textbook started its exploration of the subject, nor will you find many of the oftentimes surprising stories Bodanis uses to illustrate his tale.

The first mobile phone was developed in 1879? Thomas Edison, inventor of the light bulb, “had a vacuum where his conscience ought to be”? Alexander Graham Bell, in part, invented the telephone to impress a girl (well, acutally the girl’s parents)? Samuel Morse stole the telegraph from a guy named Joseph Henry and patented it, but not before he ran for mayor of New York City on an anti-black, anti-Jew, and, most especially, anti-Catholic platform? None of that was in my high school science textbook and such is the authority of the textbook that I have a hard time believing some of it. You’re thinking maybe Bodanis is embellishing for the sake of making a more exciting story (history + electricity? wake me when it’s over!), but then you get to the 50 pages of notes and further reading on the subject and realize he’s shooting straight and science is more strange, exciting, and sometime seedy than your teachers let on.

Two years ago, Stephen Dubner wrote an article for the NY Times Magazine on Steven Levitt, an economist with a knack for tackling odd sorts of problems. Last year, Dubner and Levitt collaborated on an article called What the Bagel Man Saw about the economic lessons gleaned from a man who’s been successfully selling bagels on the honor system in offices for more than 20 years. Now Levitt and Dubner are out with a new book called Freakonomics: A Rogue Economist Explores the Hidden Side of Nearly Everything, an overview of Levitt’s work and collaborations with other economists.

Dr. Levitt was kind enough to answer a few questions I had about the book:

jkottke: In Freakonomics, you state that you’re interested in applying economic tools to “more interesting” subjects than what one may have learned about in my high school economics class. What’s your definition of economics? Is it a tool set or a science or what?

Steven Levitt: I think of economics as a worldview, not a set of topics. This worldview has a few different pieces. First, incentives are paramount. If you understand someone’s incentives, you can do a pretty good job of predicting their behavior. Second, the appropriate data, analyzed the right way are key to understanding a problem. Finally, political correctness is irrelevant. Whatever the answer happens to be, whether you think it will be popular or not, that is the answer you put forth.

jkottke: Your talent for ignoring seemingly applicable but ultimately irrelevant information (not that different from a professional-grade batter taking cues from certain aspects of a pitcher’s mechanics and ignoring the extraneous ones in order to hit well), where does that come from? Good genes or was it all the books in your childhood home?

Levitt: If nothing else, I had an unusual home environment. My father is a medical researcher whose claim to fame is that he is the world’s expert on intestinal gas (he’s known as the King of Farts). My mother is a psychic who channels books. From an early age, my life was different from that of other kids. For instance, when I was in junior high, my father would wake me up at night to drill me with questions in hopes that I would be the star of the local high school quiz show.

jkottke: In looking at the world through data, you’ve investigated cheating schoolteachers, falling crime rates due to abortion, and the parallels between McDonald’s corporate structure and the inner workings of a crack-dealing gang. What’s the oddest or most surprising thing you’ve uncovered with this approach? Maybe something you still can’t quite believe or explain?

Levitt: It’s not the oddest result I’ve ever come up with, but there is one finding I have always puzzled over: when cities hire lots of Black cops, the arrest rates of Whites go up, but no more Blacks get arrested. When cities hire White cops, the opposite happens (more Black arrests, no more White arrests). It was an amazingly stark result, but I’m not quite sure what the right story is.

jkottke: In the chapter on the effect of abortion on crime rates, you and Stephen take care emphasizing what the data says and the strong views that people in the US hold on the issue of abortion. Still, if someone wants to twist your observations into something like “abortion is good because it lowers crime”, it’s not that difficult. Have your observations in this area caused any problems for you? Any extreme reactions?

Levitt: I have gotten a whole lot of hate mail on the abortion issue (as much from the left as from the right, amazingly). What I try to tell anyone who will listen — few people will listen when the subject is abortion — is that our findings on abortion and crime have almost nothing to say about public policy on abortion. If abortion is murder as pro-life advocates say, then a few thousand less homicides is nothing compared to abortion itself. If a woman’s right to choose is sacrosanct, then utilitarian arguments are inconsequential. Mainly, I think the results on abortion imply that we should do the best we can to try to make sure kids who are born are wanted and loved. And it turns out that is something just about everyone can agree on.

jkottke: In the book, you say “a slight tweak [in incentives] can produce drastic and unforseen results”. If you were the omnipotent leader of the US for a short time, what little tweak might you make to our political, cultural, or economic frameworks to make America better (if you can forgive the subjectivity of that word)?

Levitt: I would start by increasing the IRS budget ten-fold and doing a lot more tax audits. If everyone paid their taxes, tax rates could be much lower and otherwise honest people wouldn’t be tempted to cheat. For some reason, everyone hates the idea. But we can’t all be cheating more than average on our taxes. I think it would be for the better. And after I got done with that, I’d legalize sports betting, and I would also do away with most of the nonsense and hassle that currently goes into airport security.

jkottke: In the war between the film and music industries and their customers, there’s an argument over how much the explosive increase in Internet piracy affects sales of CDs, movie tickets, and DVDs. Using the same data, the music/movie industry argues that sales are down because of piracy (or at least diminished from what they “should” be in a piracy-free marketplace) while the other side argues that sales are up and that piracy may actually have a beneficial effect. The question of “how does piracy affect record/movie sales?” seems well suited to your particular application of economic tools. Have you looked at this question? And if not, do you have sense of which special view of the data might reveal an answer?

Levitt: I have not myself studied the issue. I have a former student who has studied this issue. Alejandro Zentner. He argues that music sales are way down as a consequence of downloading. He uses the availability/price of high-speed internet across areas and relates that to patterns of self-reported music buying.

But on the other hand, I have a good friend Koleman Strumpf who has also written on this and comes to the opposite conclusion using a whole bunch of clever arguments.

This is a great issue - an important one and a tough one. Having studied both of these papers, I don’t know which one to believe.

—-

Thanks, Steven. For more information on Freakonomics, check out the book’s web site — which includes a weblog written, in part, by the authors — or buy the book on Amazon. Check out also this email conversation between Levitt and Steve Sailer on the connection between legalized abortion and reduced crime in the 1990s, a short profile in Wired, and this profile in Esquire (free subscription required).

Update: Here’s a Freakonomics excerpt from Slate on how distinctively black or white names affect a child’s course in life.

January was a rough month for me and I needed a break from all the “heavy” nonfiction I usually read, so I picked up Susanna Clarke’s Jonathan Strange and Mr. Norrell, a well-received fantasy novel. I’m normally not much of a fantasy reader, but I was in the mood for something fanciful and besides, JS&MN isn’t really fantasy. It contains fantastic things like magicians, Raven Kings, and faeries but belongs more to the 19th century British novel genre…more Jane Austen than JRR Tolkien. (Clarke lists Austen as her favorite author on the book’s site.)

And it’s just plain good, whatever the genre. The simple bold cover drew me in (it looks like the font used is a close cousin to Caslon Antique), but the plot kept me in “I can’t put it down” mode until I had finished. A surprise was how clever and funny Clarke’s writing was…I found myself laughing out loud several times at the book’s cutting deadpan wit. The book weighs in at ~780 pages, but my only disappointment upon finishing was that the story was over…I felt like I’d just gotten to know the characters and wanted to follow them on all sorts of adventures. Luckily, Clarke is working on a sequel of sorts, according to the book’s web site:

The next book will be set in the same world and will probably start a few years after Jonathan Strange & Mr Norrell finishes. I feel very much at home in the early nineteenth century and am not inclined to leave it. I doubt that the new book will be a sequel in the strictest sense. There are new characters to be introduced, though probably some old friends will appear too. I’d like to move down the social scale a bit. Strange and Norrell were both rich, with pots of money and big estates. Some of the characters in the second book have to struggle a bit harder to keep body and soul together. I expect there’ll be more about John Uskglass, the Raven King, and about how magic develops in England.

The first chapter is online if you’d like to read it and Metacritic has several reviews.

P.S. For fun, here are Amazon’s Statistically Improbable Phrases for this book: new manservant, madhouse attendants, fairy roads, practical magician.

Tufte has posted a new chapter from his upcoming book, Beautiful Evidence. Chapter is called “Corrupt Techniques in Evidence Presentations”, some of the ugly evidence in the book.

A few weeks months ago, I chose this book as the first official selection of the unofficial kottke.org book club. The idea of the book club is that I tell you what book I’m going to read next, you can read along if you’d like, and then we get together to discuss it in the comments of a thread like this one.

What a terrible idea…I apologize for even suggesting it. I have trouble reviewing books as it is without the added pressure of a deadline and having people (if any of you actually chose to follow along) who read the book depending on me getting some sort of rip-roaring conversation going. As a result, even though I finished the book weeks and weeks ago, I’ve been avoiding writing this review. However, since I got myself into this, I’m going to give it a shot and hope that someone else can rescue us with a thoughtful, knowledgeable review of the book and/or the comics format in the comments. Here we go.

Many of my friends are into comics in one way or another. I never was, not even as a kid (ok, not exactly true…I really liked Bloom County). I go into comic shops, thumb through comic books and graphic novels, and leave wondering what the hell all the fuss is about. I guess you could say I don’t get comics. Which is odd because as a sort of socially awkward dork, I should identify with many of the characters in the stories and the artists drawing them (and I mean that in a good way).

A few years ago, I bought Chris Ware’s perfect Jimmy Corrigan: The Smartest Kid on Earth, one of my all-time favorite pieces of media. But that’s been the exception to the rule for me and comics. McSweeney’s #13 contained a comic by Chris Ware (he designed the wonderful dust cover as well); it, The Little Nun strips by Mark Newgarden, and the wonderfully spare comics by Richard McGuire (which reminded me of Powers of Ten) were the highlights for me.

So instead of a review, a question. What am I missing here? Why do you enjoy comics and/or graphic novels? I can guess why they are appealing, but I’d rather hear about it from you guys.

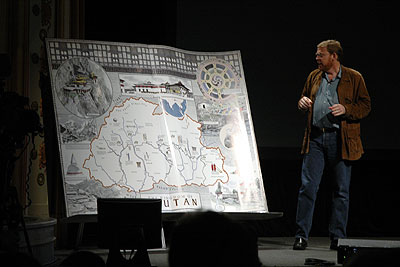

Michael Hawley gave the Poptech audience a wonderful tour of Bhutan and the giant book that resulted from his journeys there. A couple of photos of the book at Poptech:

Turning the pages involved a short walk. If you’d like to own this baby, it’s available for only $10,000 on Amazon.

Salon nails the gist of Oblivion:

With his new story collection, David Foster Wallace has perfected a particularly subtle form of horror story — so subtle, in fact, that to judge from the book’s reviews, few of his readers even realize that’s what these stories are.

Exactly right. It’s Stephen King for the literary crowd. In many of the stories, there’s always something lurking off frame…the oblivion, as it were. Wallace knows, as does Scott McCloud, that what happens between the frames makes the narrative. Wallace never shows us the monster…the reader just gets glimpses of its shadow and is left with a feeling of unease. As opposed to the horror movies of today with their gore and choreographed multimedia frights, the seeming normalcy of Wallace’s stories set the reader up for a later sense of discomfort.

Not wanting to drag my current hardcover with me to the beach, I grabbed The Great Gatsby off the shelf as I left the apartment this morning. I cracked it open on the platform as I waited for the subway and continued reading on the train. Once I arrived at Rockaway Beach, I had a quick lunch and walked down the boardwalk to find a good spot for me and my blanket. Between swims and relaxing naps in the sun, I continued reading. A few hours later, I got back on the train toward Manhattan, reading all the way. As the train slowed for its stop at 14th Street, I read the final paragraph, closed the book, and stood just in time for the doors to snap open in front of me. Fitzgerald, some 80 years ago, must have written the book just for my trip today.

Preview pages about Feynman diagrams from Tufte’s Beautiful Evidence.

“The problem with the global village is all the global village idiots.”

— Paul Ginsparg

“You don’t do good software design by committee.”

— Donald Norman

“There’s no justice like angry-mob justice.”

— Principal Seymour Skinner

“A person is smart. People are stupid.”

— Agent K

The wisdom of crowds you say? As Surowiecki explains, yes, but only under the right conditions. In order for a crowd to be smart, he says it needs to satisfy four conditions:

1. Diversity. A group with many different points of view will make better decisions than one where everyone knows the same information. Think multi-disciplinary teams building Web sites…programmers, designers, biz dev, QA folks, end users, and copywriters all contributing to the process, each has a unique view of what the final product should be. Contrast that with, say, the President of the US and his Cabinet.

2. Independence. “People’s opinions are not determined by those around them.” AKA, avoiding the circular mill problem.

3. Decentralization. “Power does not fully reside in one central location, and many of the important decisions are made by individuals based on their own local and specific knowledge rather than by an omniscient or farseeing planner.” The open source software development process is an example of effect decentralization in action.

4. Aggregation. You need some way of determining the group’s answer from the individual responses of its members. The evils of design by committee are due in part to the lack of correct aggregation of information. A better way to harness a group for the purpose of designing something would be for the group’s opinion to be aggregated by an individual who is skilled at incorporating differing viewpoints into a single shared vision and for everyone in the group to be aware of that process (good managers do this). Aggregation seems to be the most tricky of the four conditions to satisfy because there are so many different ways to aggregate opinion, not all of which are right for a given situation.

Satisfy those four conditions and you’ve hopefully cancelled out some of the error involved in all decision making:

If you ask a large enough group of diverse, independent people to make a prediciton or estimate a probability, and then everage those estimates, the errors of each of them makes in coming up with an answer will cancel themselves out. Each person’s guess, you might say, has two components: information and error. Subtract the error, and you’re left with the information.

There’s more info on the book at the Wisdom of Crowds Web site and in various tangential articles Surowiecki’s written:

- Blame Iacocca - How the former Chrysler CEO caused the corporate scandals

- Search and Destroy (on Google bombs)

- The Pipeline Problem (drug companies)

- Hail to the Geek (government and information flow)

- Going Dutch (IPOs)

- The Coup De Grasso (fairness in business)

- Open Wide (movies and “non-informative information cascades”)

Some running notes:

What I find most useful about reading Jacobs is how well her arguments scale. They’re scale-free arguments. Through her discussion of large cities in The Death and Life of Great American Cities and of entire civilizations in this book, you can see instantly how the problems and solutions she examines could be used to describe smaller entities like towns, families, large corporations, project teams, blogospheres, online communities, etc.

Dark Age Ahead is ultimately another in the this-world-is-going-to-hell genre of media, but Jacobs makes it seem OK somehow. Maybe it’s because she’s really concerned about it and not selling fear like everyone else?

Several mentions of Canada and Toronto (Jacobs’ current place of residence) in the book so far. I wonder about generalizations being made about specific situations in Toronto; something to keep in mind.

Jane Jacobs hates cars. Absolutely can’t stand them. I thought this book was about a possible coming dark age, not her dislike of automobiles.

As I’m reading, I’m flipping back to the endnotes. Many of her sources are either the Toronto Star or private conversations she’s had with people. One gets the mental picture of an elderly woman sitting at her breakfast table, reading the newspaper to guests, and getting so worked up about it all that she writes a book about the coming dark age.

Best chapter is Dumbed Down Taxes, about how the collection and distribution of funds by the government has become disconnected with the needs of people. Jacobs makes the excellent point that maybe the rules and structure we came up with for governing the county 200 years ago isn’t necessarily the best way to go about it now and should be reexamined. Why is New York City part of a state? Does it benefit the state or the city in any way? And what about states? Do they still make sense? (And don’t even get me started on the electoral college.)

Before I bought this book, I looked it up on Amazon and read a review by Dr. J. E. Robinson called The Title and Book Jacket Do Not Match the Text Inside (you’ll have to scroll for the review…Amazon annoyingly doesn’t permalink individual reviews). When I first read the review (2/5 stars), I thought it unfair. Now having finished the book, I still think the review was largely unfair, but Dr. Robinson does have a point. In trying to make her points (which, when she stated them in chapter 1, I thought were excellent), Jacobs is all over the place and seldom manages to clearly support her arguments. Not that the examples she cites aren’t eventually relevant (after all, a dark age pretty much affects everything in a culture), but they don’t go directly to her main points. I would have loved more focus.

Doing a lot of complaining, but really, there lots of excellent stuff here. The individual stories and passages contained in the book would have made a great series of magazine articles or a fantastic weblog.

Tufte has revised his chapter on sparklines. Sparklines are “intense, simple, word-sized graphics”.

This seems familiar:

It made Feynman think wistfully about the days before the future of science had begun to feel like his mission — the days before physicists changed the universe and became the most potent political force within American science, before institutions with fast-expanding budgets began chasing nuclear physicists like Hollywood stars. He remembered when physics was a game, when he could look at the graceful narrowing curve in three dimensions that water makes as it streams from a tap, and he could take the time to understand why.

Sparklines are “intense word-sized graphics”. From Tufte’s upcoming book, Beautiful Evidence

Evidence (ahem) that Tufte is indeed working on his new book, Beautiful Evidence.

How well does the 6 year-old analysis of how we use and will use information technology contained in the pages of Interface Culture hold up? Not too bad, actually. Consider the following paragraph from the “Windows” chapter on what metaforms the Web might be capable of supporting (paragraph breaks and links mine):

Over the next decade, this stitching together of different news and opinion sources will slowly become a type of journalism in its own right, a new form of reporting that synthesizes and digests the great mass of information disseminated online everyday. (Clipping services have occupied a comparable niche for years, though their use is largely limited to corporate executives and other journalists.)

Total News gives us a glimpse of what these new information filters will look like, but the site neglects the defining element of a successful metaform, which is an actual editorial or evaluative sensibility. Total News simply repackages the major online news services indiscriminately; it may be a more convenient format, but it adds nothing to the actual content of the information. More advanced news “browsers” will include a genuine critical temperament, a perspective on the world, an editorial sensibility that governs the decisions about which stories to repackage. The possibilities are endless: a filter for left-leaning economic and political stories; a filter for sports coverage that emphasizes the psychological dimension of professional athletics; a filter that focuses exclusively on independent film news and commentary.

The beautiful thing about this new meta-journalism is that it doesn’t require a massive distribution channel or extravagant licensing fees. A single user with a Web connection and only the most rudimentary HTML skills can upload his or her overview of the day’s news. If the editorial sensibility is sharp enough, this kind of metajournalism could easily find enough of an audience to be commercially sustainable, given the limited overhead required to run such a service.

When the whole blog thing blew up huge and then people like Rafat Ali, Andrew Sullivan, and Nick Denton started making money off of them, Johnson must have danced around the apartment in his underpants (perhaps like Tom Cruise in Risky Business) shouting, “I told you so, I told you so, I called the hell out of that one! In your face!”

DFW is a favorite of mine, but I was disappointed in Everything and More. Perhaps I wasn’t part of the intended audience, but with an interest in all things Wallace, a college degree in physics, a general interest in mathematics, and avid reader of popular science books, if not me, then for whom was this book written?

Mostly I was bothered by Wallace’s signature writing style, which usually challenges the reader in delightful ways. In E&M, he ratcheted his style up to such a degree that it became as obfuscating as the math he was trying to explain. Not that he should have used only words of four letters or less, but a greater degree of clarity and simplicity would have been appreciated to let the parodoxical beauty and the beautiful paradox of transfinite math show (which Jim Holt did more successfully than Wallace in his New Yorker review of the book).

As competitive and crazy as he makes the CIA (Culinary Institute of America) sound, I was surprised that, even though he didn’t attend a full slate of classes or do an externship like all of his classmates, Ruhlman was not only able to keep up with everyone, but seemed to excel at times. And somehow, he was able to take notes about what he was doing and conversations he had with instructors and classmates.

From the book jacket, the lazy reviewer’s friend:

Chip Kidd is renowned and revered as a maverick graphic designer. Specifically, Kidd’s book jacket designs for such major New York publishers as Alfred A. Knopf are among the most significant and innovative of our time. This richly illustrated book-the first critical selection of Kidd’s design work-looks closely at this contemporary visual pioneer. Veronique Vienne presents a full and nuanced view of Kidd, discussing how he has developed celebrity status as a designer, design critic, lecturer, and editor. She also relates how Kidd is greatly influenced by popular culture, noting his vast collection of Batman memorabilia. Vienne concludes by examining Kidd’s editorial involvement with books on cartoonists as well as his own first novel, The Cheese Monkeys, published in 2001 to critical acclaim. Chip Kidd reveals the fascinating life and career of a revolutionary graphic designer with a winning public persona, whose ambitions now also lean toward editing and writing. The book will appeal to anyone involved in design and popular culture as well as admirers of Kidd’s extraordinary creative spirit.

I was reading a piece by David Sedaris the other day and it contained a passage wherein something happened and a character in the story reacted to it, which is not unusual except that he somehow found space inbetween to write 2-3 additional sentences without interrupting the flow of the story. In Understanding Comics, Scott McCloud talks about this idea in the context of comics:

See that space between the panels? That’s what comics aficionados have named “The Gutter!” And despite its unceremonious title, the gutter plays host to much of the magic and mystery that are at the very heart of comics! Here in the limbo of the gutter, human imagination takes two separate images and transforms them into a single idea.

While McCloud relies on human imagination to fill in the gaps, Sedaris recognizes one of the endless numbers of gaps that may be filled in a prose narrative and does so great effect.

I was just at the Barnes and Noble on 48th & 5th. Jimmy Fallon and his sister were there signing copies of their new book, I Hate This Place: The Pessimist’s Guide to Life. As I browsed through a couple of magazines, I noticed three girls standing in the bargain books aisle. Well, everyone in the store noticed them standing there because one of them was crying and shrieking uncontrollably and her two friends were taking turns calming her down or revving her up.

“Oh my God! I can’t believe Jimmy Fallon kissed me!!”

“I know!!!”

[They all scream.]

“I’m never going to wash this cheek again.”

[Sobbing intensifies. The girl is alternating between trying to regain her composure and going completely bats with the crying. She’s having a hard time standing.]

This goes on for a minute or two. Then a woman, dressed to the nines and obviously a lifelong New York resident, annoyed that these silly girls are between her and whatever purchases she wants to make, pushes by them while loudly announcing to the rest of the store, “my God, I don’t understand what the big deal is, seeing some guy and then crying like a baby, yelling, and blocking the aisle. I hate this fucking store.”

Since Lewis writes primarily on business, business folks will undoubtably read Moneyball with an eye toward picking up some pointers on how to run their companies. Some will completely misunderstand what Lewis discovered about major league baseball and beefheadedly apply their new “knowledge”. The lesson of Moneyball is not that there are potential employees out there that are cheaper than your current employees. That’s the holy grail of large American corporations and exactly what they would want to hear.

As Lewis reports, what Oakland actually did is a) measure player statistics as objectively as they could, b) identify players that perform well in those statistical categories, c) discover that the players they valued were not valued by other teams and were therefore relatively cheap, and d) went out and got the players they wanted at bargain prices. As much as the business person would like to skip directly to step d, it’s impossible to determine if that will actually be effective unless you do the a-c analysis first.

I was somewhat disappointed in the 2003 edition of this collection, especially after enjoying so much the last three editions. Perhaps Oliver Sacks and I disagree on what makes science writing good. The two best articles were 1491 by Charles Mann about what the Americas were like before Columbus landed and the effect of the European arrival:

In North America, Indian torches had their biggest impact on the Midwestern prairie, much or most of which was created and maintained by fire. Millennia of exuberant burning shaped the plains into vast buffalo farms. When Indian societies disintegrated, forest invaded savannah in Wisconsin, Illinois, Kansas, Nebraska, and the Texas Hill Country. Is it possible that the Indians changed the Americas more than the invading Europeans did? “The answer is probably yes for most regions for the next 250 years or so” after Columbus, William Denevan wrote, “and for some regions right up to the present time.”

and Atul Gawande’s The Learning Curve, an article on how doctors need to learn on the job (while potentially making costly mistakes) in order to become more effective overall:

In medicine, there has long been a conflict betwenn the imperative to give patients the best possible care and the need to provide novices with expericne. Residencies attempt to mitigate potential harm through supervision and graduated responsibility. And there is reason to think that patients actually benefit from teaching. But there is no avoiding those first few unsteady times a young physician tries to put in a central line, removes a breast cancer, or sew together two segments of colon. No matter how many protections are in place, on average these cases go less well with the novice than with someone experienced.

Jared Diamond has written a fantastic book that lays out in simple terms how Europeans came to dominate the rest of the world without resorting to racist notions of Europeans being intrinsically smarter or more gifted than the inhabitants of the rest of the world. Diamond’s thesis is so simple and powerful, it seems, as Erdos would say, to come from “God’s book of proofs”. An illustration of this powerful simplicity is how the orientation of the continents affected the spread of domestication of crops, animals, germs, and ideas (which in turn influenced how fast difference cultures matured):

Why was the spread of crops from the Fertile Crescent so rapid? The answer partly depends on that east-west axis of Eurasia with which I opened this chapter. Localities distributed east and west of each other at the same latitude share exactly the same day length and its seasonal variations. To a lesser degree, they also tend to share similar diseases, regimes of temperature and rainfall, and habitats or biomes (types of vegetation). That’s part of the reason why Fertile Crescent [crops and animals] spread west and east so rapidly: they were already well adapted to the climates of the regions to which they were spreading.

I’ve read so much about science that I was reluctant to pick up Bryson’s book, but I’m a sucker for good but accessible science writing, so I forged ahead anyway. The beginning of the book was interesting but nothing I hadn’t heard before, but once Bryson got to the more recent developments in everything from physics to evolutionary biology, I was hooked. I try to keep up with where science stands today by reading magazine and newspaper articles, but the big picture is hard to visualize that way. Bryson painted that big picture…the last few chapters of the book should be required reading for high school science students who may have learned that protons, neutrons, and electrons are indivisible or that Darwin had the first and final say on how evolution works.

Stay Connected