kottke.org posts about art

The latest exhibition by art duo FriendsWithYou is currently on view at Dallas Contemporary and includes a piece called The Dance that features two fuzzy orb-ish heads that slowly bobble around the room.

An interactive and communal experience, the exhibition actively incorporates audiences: two moving orbs serve as ambassadors as they meander along in a spiritual, cleansing, and comforting ritual set to a custom soundtrack in celebration of the beauty and power of togetherness.

You can see The Dance in motion on FriendsWithYou’s Instagram here and here. Natalie Gempel wrote about what it was like to pilot one of the orbs.

Submerged in my pink bubble, I spin, wobble, and drift aimlessly. Between the darkness and the humming of the air compressor, it’s almost like being in a sensory deprivation tank. I’m brought out of my haze when Carolina Alvares-Mathies, the Contemporary’s new Deputy Director, comes to check on me. It’s been cool, but I’m ready to exit.

The zipper opens and I stumble out. I don’t remember being born, but I assume it’s a similarly jarring feeling. Everything is too bright and I’m a little queasy. Still, I reentered the real world with the information I needed: It was weird in there, but I did have fun.

(thx, jenni)

In less than a minute, this Senegalese sand artist working on the island of Gorée creates a portrait by pouring sands of different colors over a wooden board with glue on it. The way that the painting emerges at the last second out of seeming disorder is a lovely shock, like a magic trick.

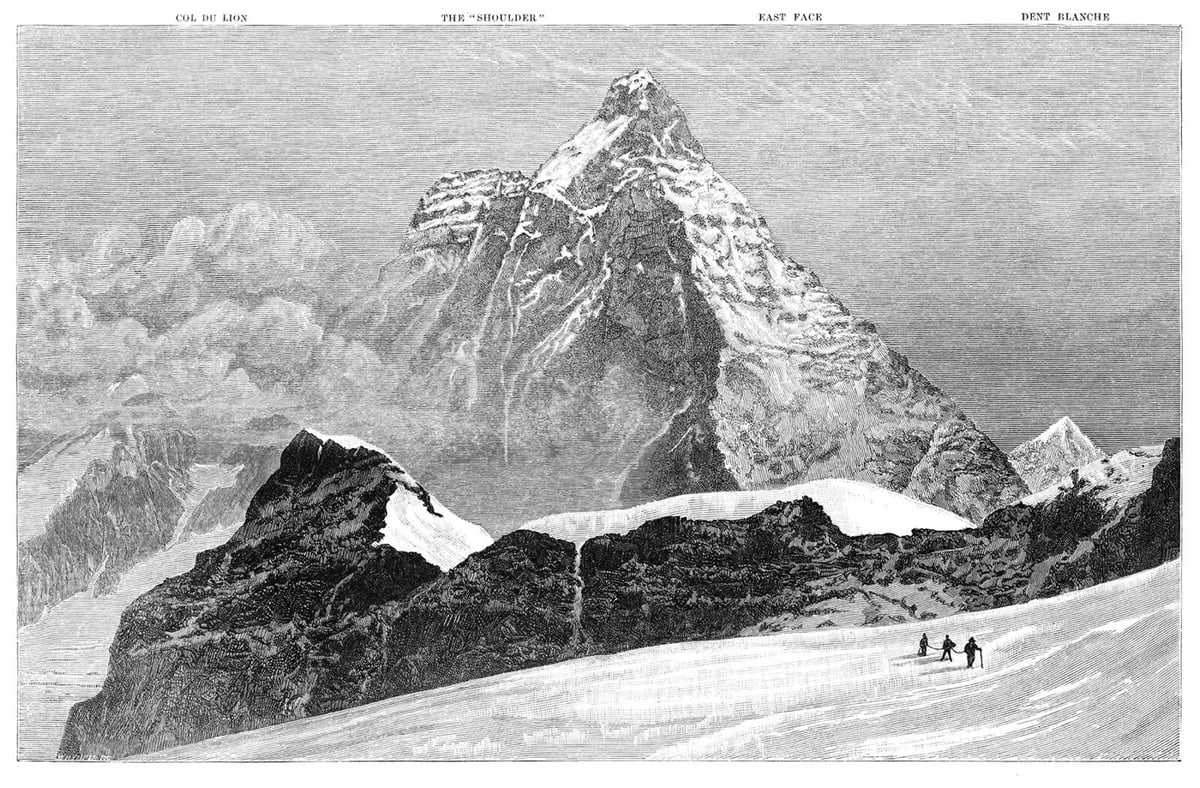

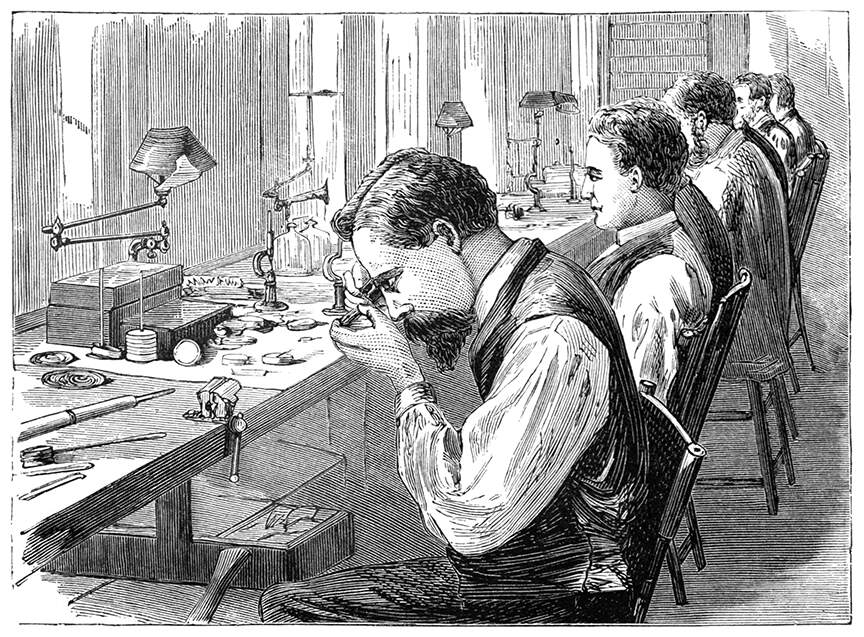

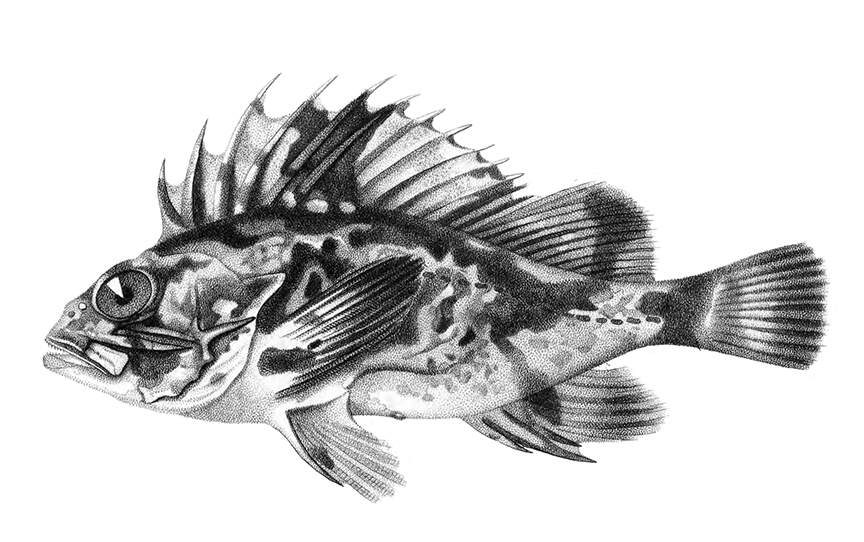

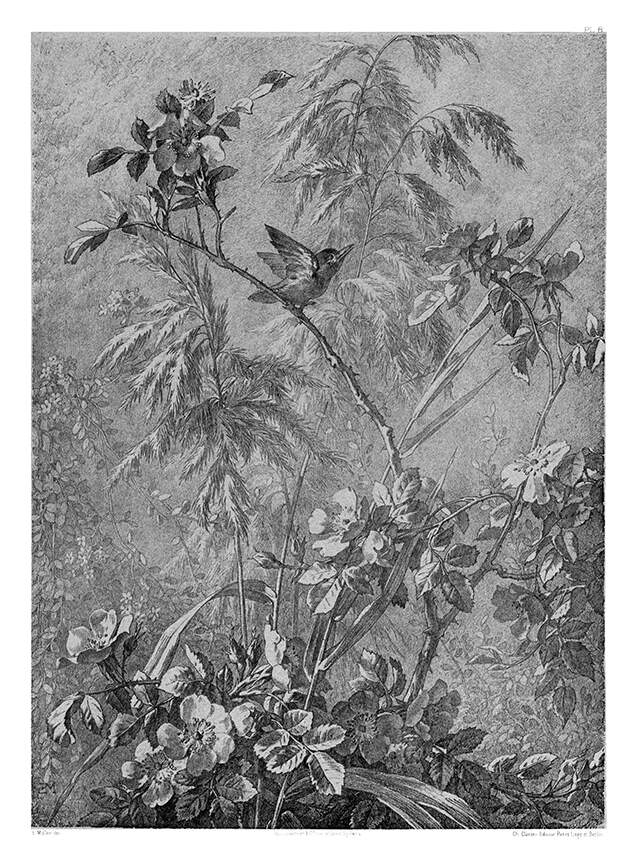

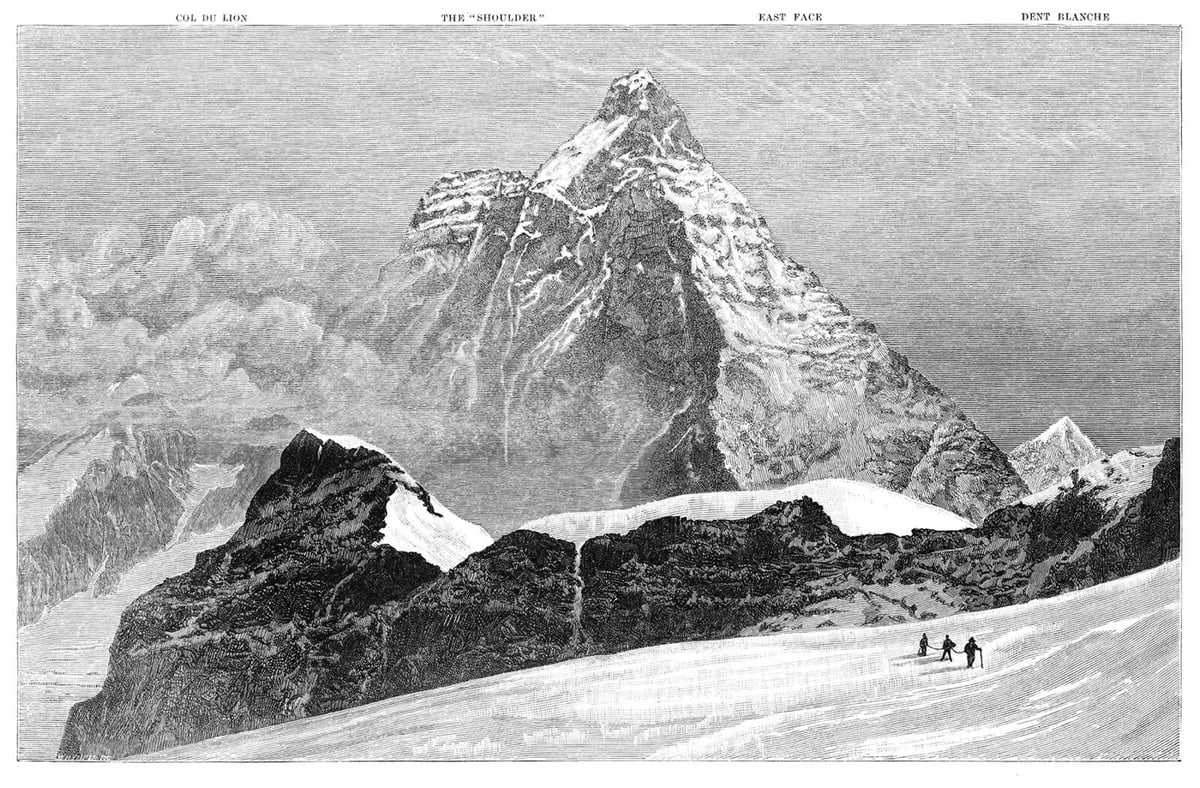

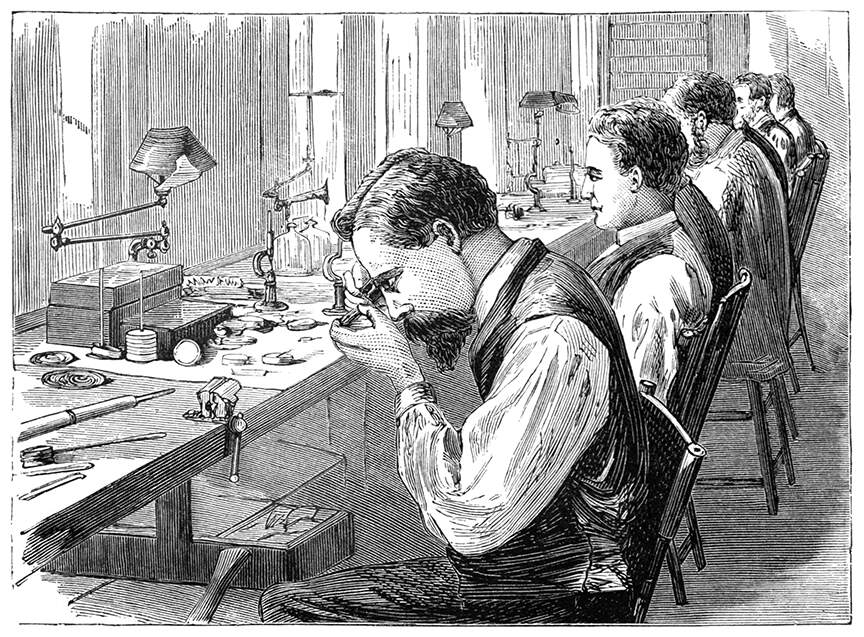

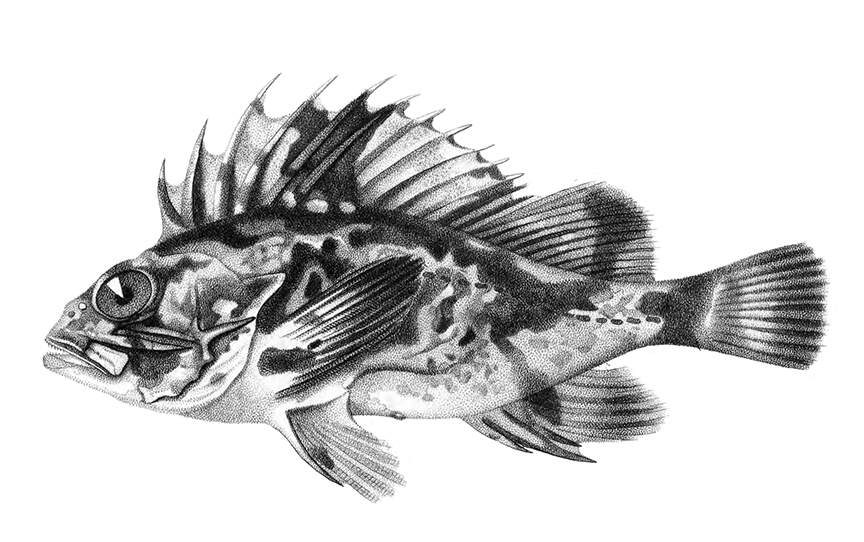

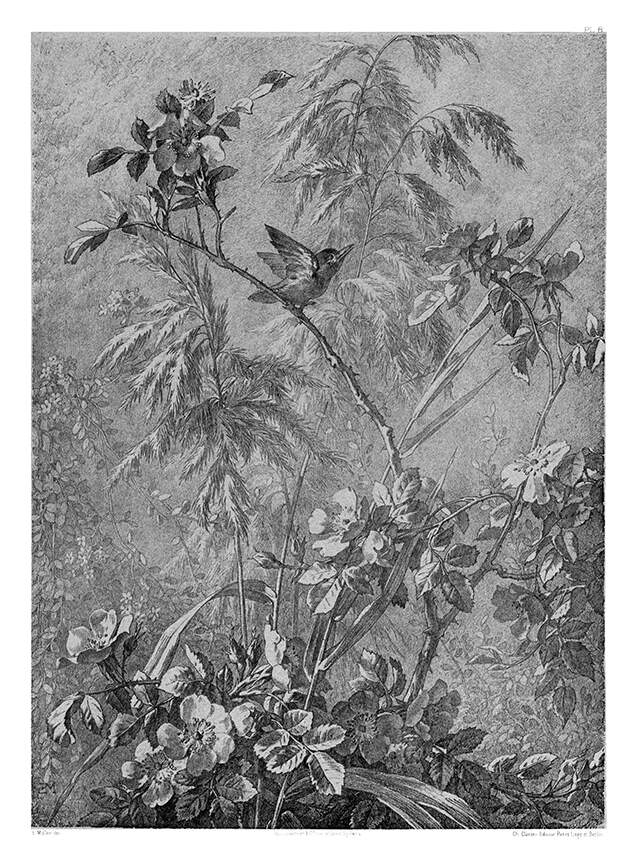

Here’s an enormous library of thousands of old book illustrations, with searchable name, artist, source, date, which book it was in, etc. There are also a number of collections to browse through, and each are tagged with multiple keywords so you can also get lost in there in that manner.

Though the team behind the site doesn’t specifically list the whole site as public domain, chances are a lot of the illustrations you’ll find are way out of copyright in most jurisdictions.

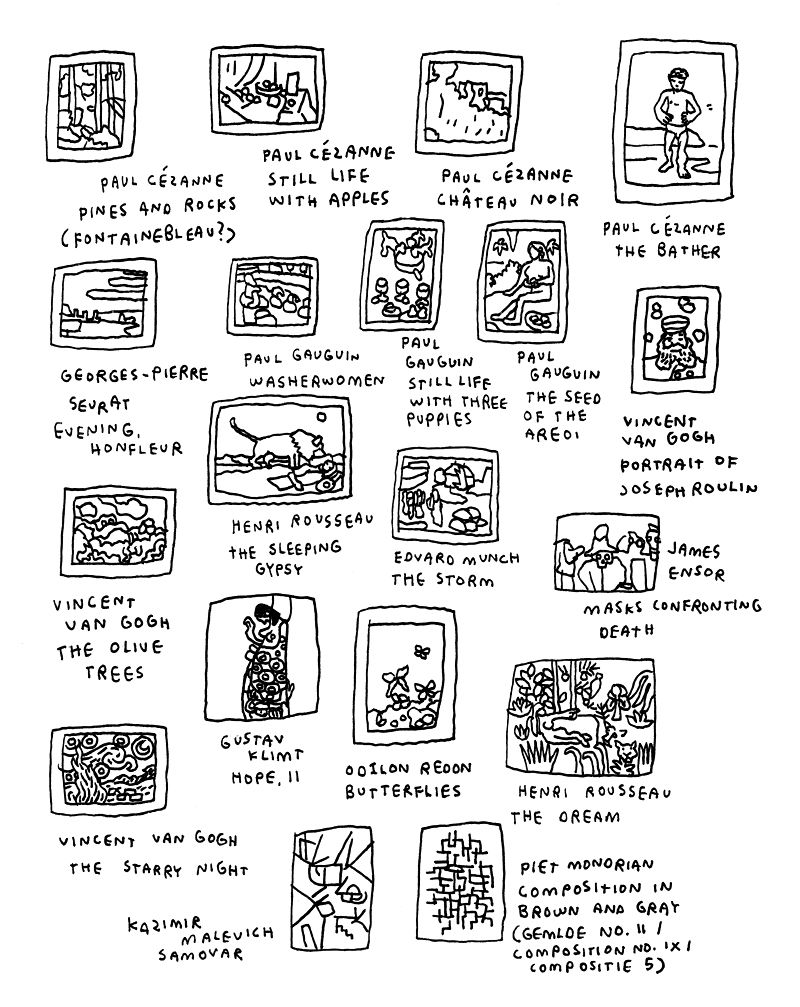

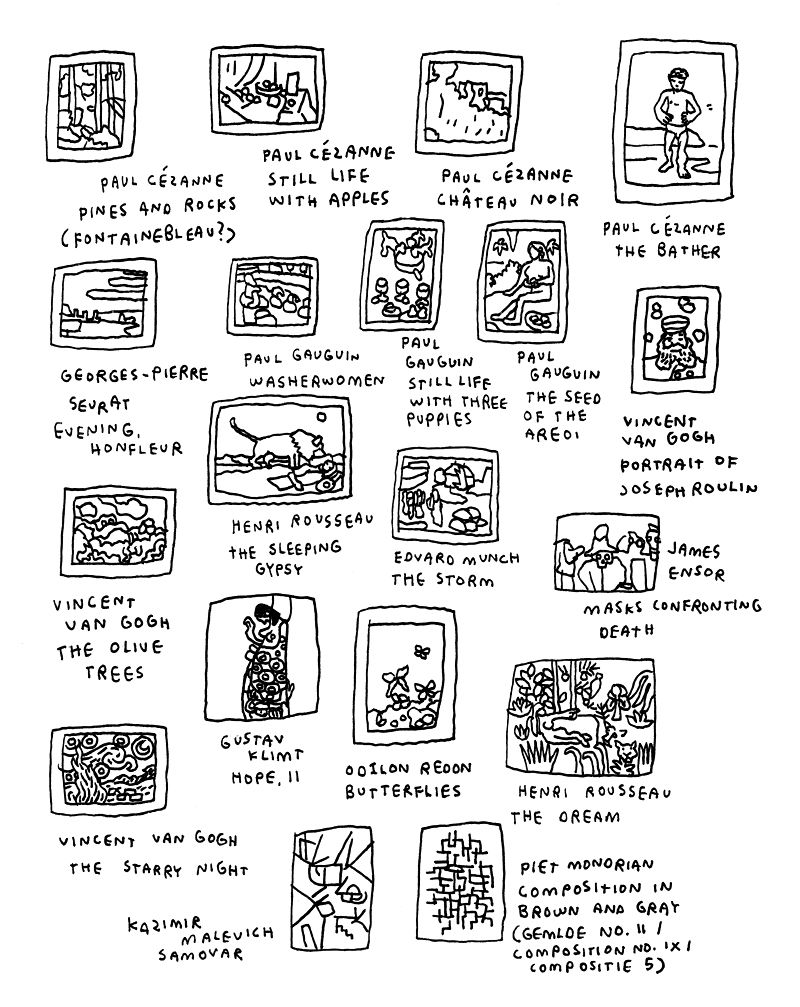

New York artist Jason Polan has passed away at the age of 37. The cause was colon cancer. From the NY Times obituary:

Mr. Polan’s signature project for the last decade or so was “Every Person in New York,” in which he set himself the admittedly impossible task of drawing everyone in New York City. He kept a robust blog of those sketches, and by the time he published a book of that title in 2015 — which he envisioned as Vol. 1 — he had drawn more than 30,000 people.

These were not sit-for-a-portrait-style drawings. They were quick sketches of people who often didn’t know they were being sketched, done on the fly, with delightfully unfinished results, as Mr. Polan wrote in the book’s introduction.

“If they are moving fast, the drawing is often very simple,” he wrote. “If they move or get up from a pose, I cannot cheat at all by filling in a leg that had been folded or an arm pointing. This is why some of the people in the drawings might have an extra arm or leg — it had moved while I was drawing them. I think, hope, this makes the drawings better.”

See also obituaries and remembrances from Gothamist and Ghostly. You can check out his blog and buy some of his work from 20x200.

I never met Polan in person — we corresponded via email occasionally, were admirers of each other’s work (I have several of his drawings), and I linked to his stuff sometimes (not enough) — but many of my friends knew him well and are reeling. There was a gentleness, a loving attention, that really came through in his work and in talking with the folks who knew him, that’s the way he was in person too. A kind soul, gone too soon. Rest in peace, Jason.

Update: Polan’s friend and long-time collaborator Jen Bekman posted a lovely tribute to him on 20x200.

Jason noticed. This was his thing. The effortlessness with which he could hone in on a person in the endless stream of the city, pick out just one or two details that made them unique and make art of them. People often asked me if I thought he had a photographic memory, and yea, maybe he did, but it wasn’t really the source of his genius. The source, I think, was his bottomless empathy and interest.

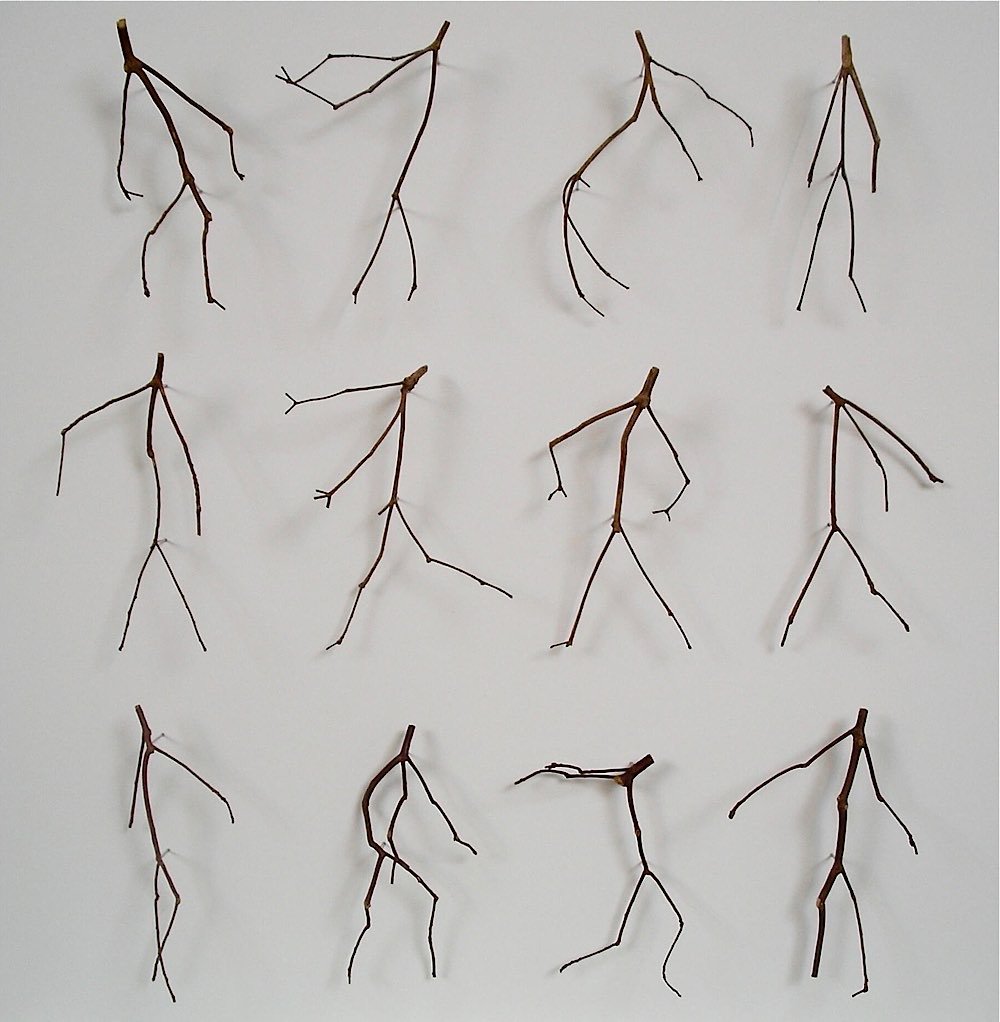

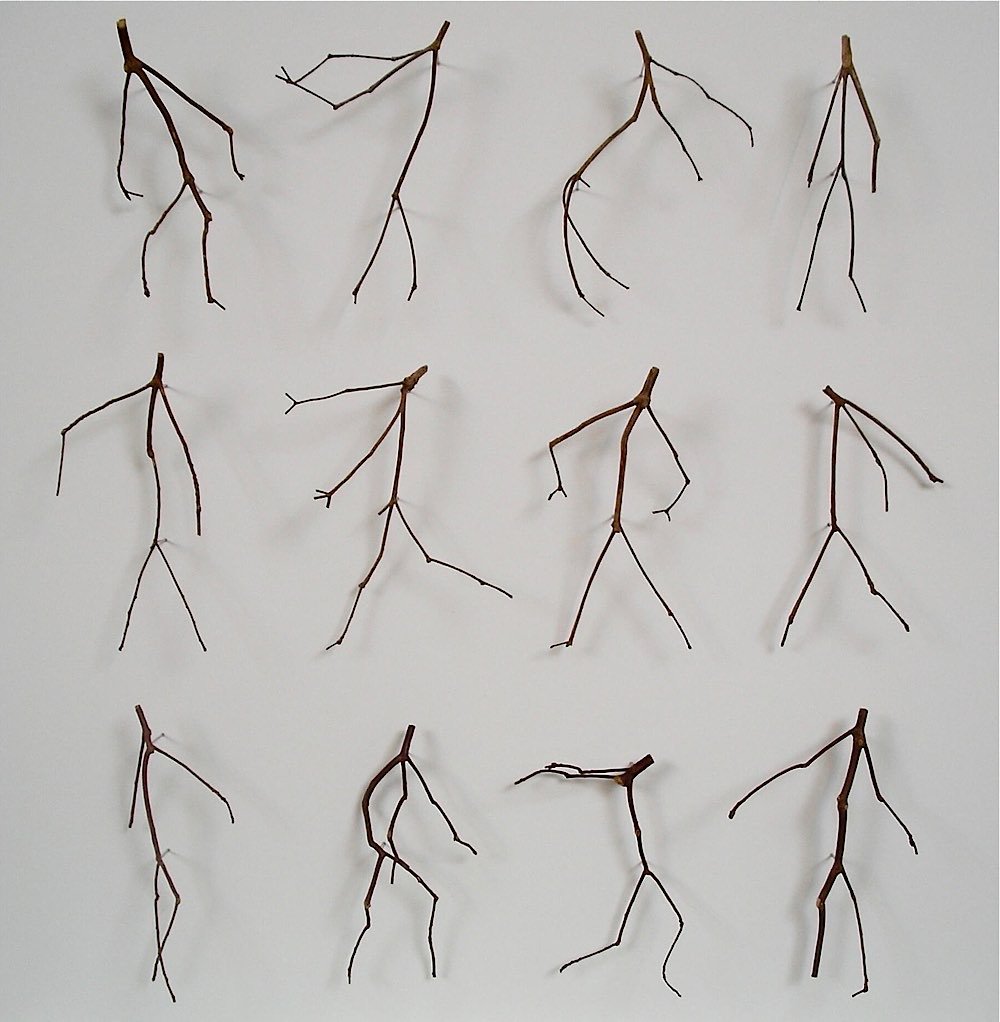

Artist Chris Kenny uses bits of twig from tree branches to make these interesting found art pieces that exploit the human tendency for pareidolia, including the one above of twigs in motion. (via @nicholsonbaker8)

Ugandan-Kenyan fashion designer Bobbin Case and Dutch artist Jan Hoek have collaborated on a project called Boda Boda Madness. Inspired by the elaborate decorations used by some boda boda (motorbike taxi) drivers in Nairobi to attract customers, Case designed costumes to go with each bike’s decorations and Hoek photographed the results. After the fact, the coordinated outfits proved good for business:

The nice thing is that because of their new outfits their income went up, so they really kept on using their costumes.

Hoek also did a project called Scooters Will Never Die, in which he worked with a group of Africa refugees in Amsterdam to customize scooters to their riders’ specifications.

(via colossal)

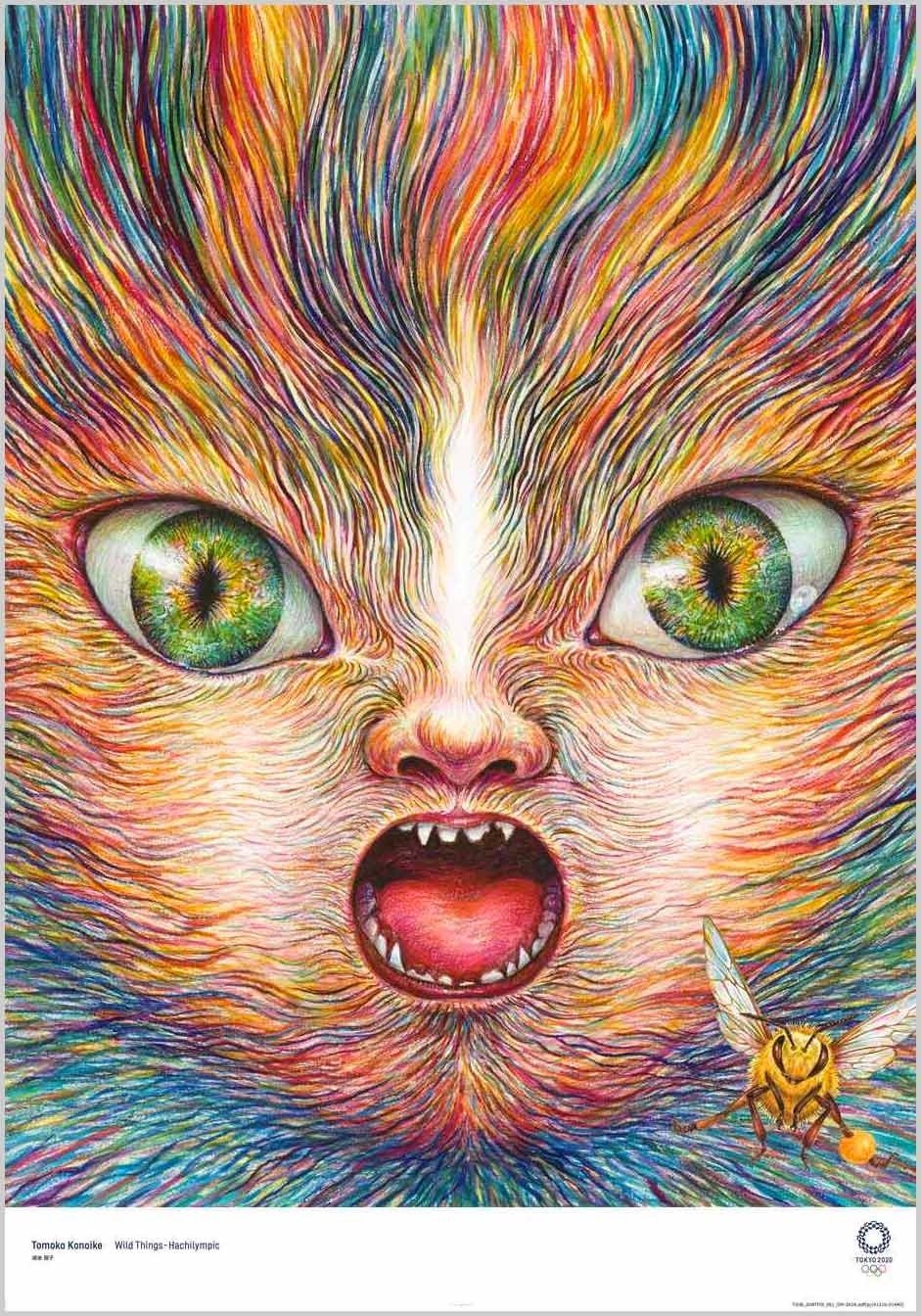

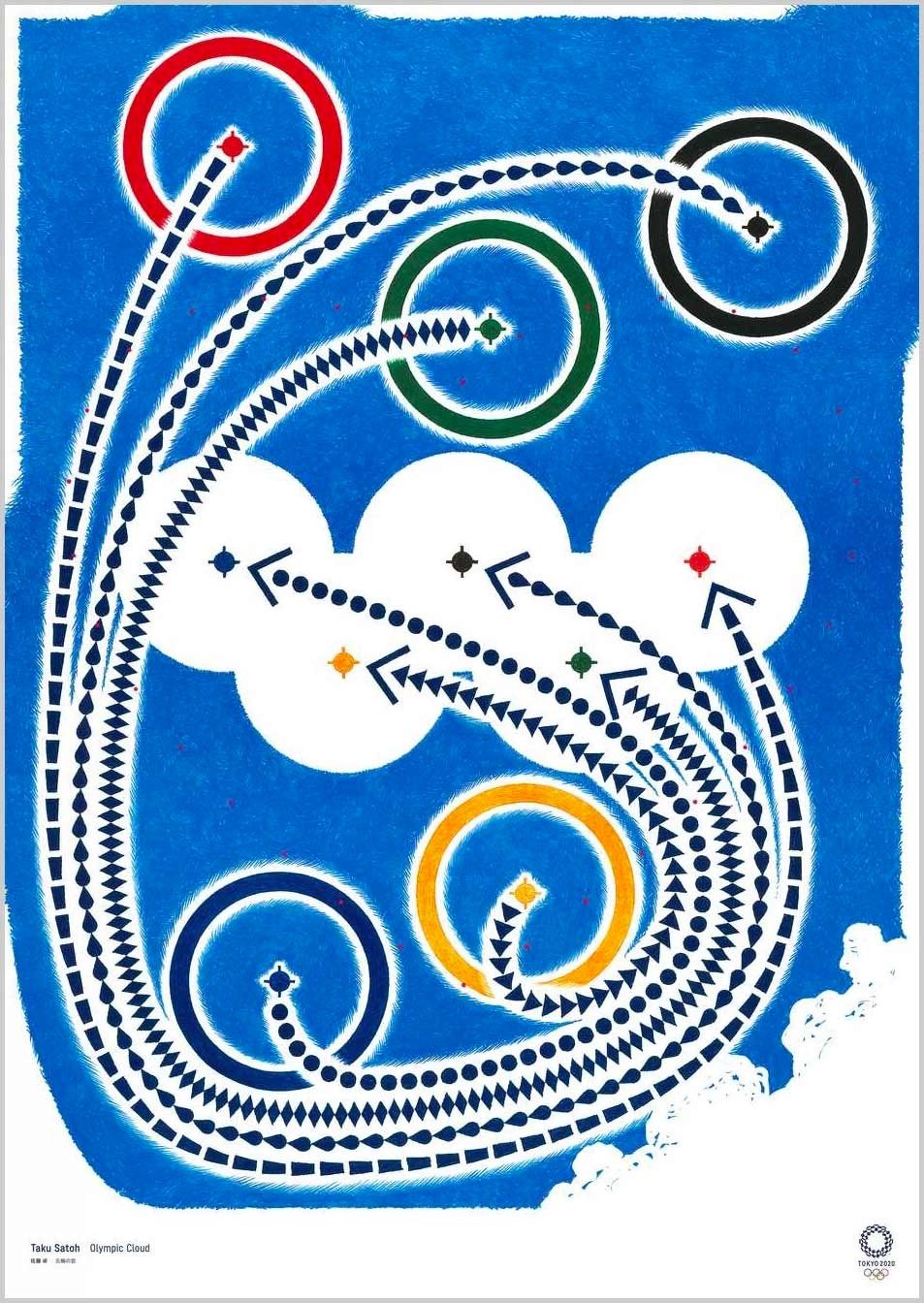

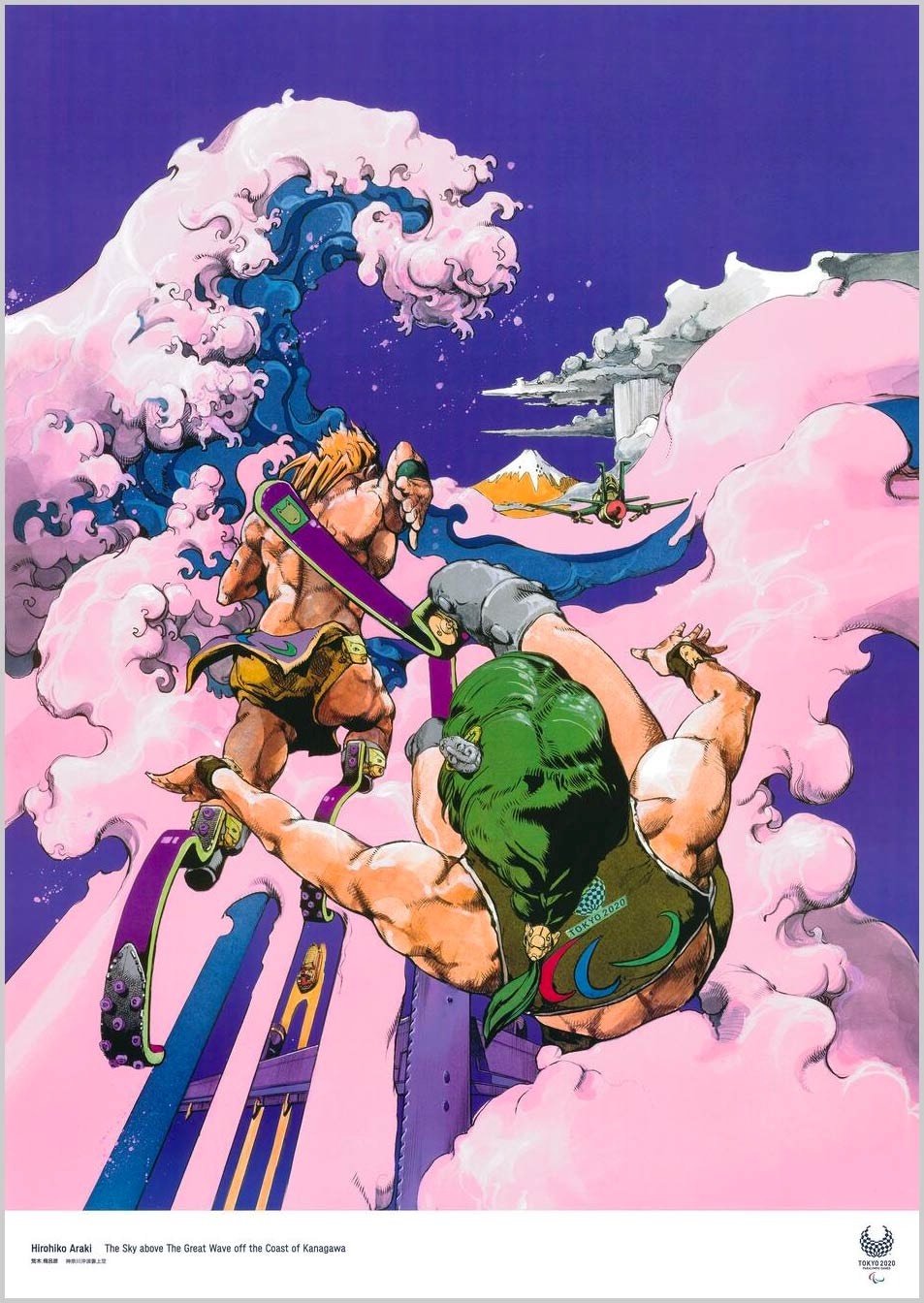

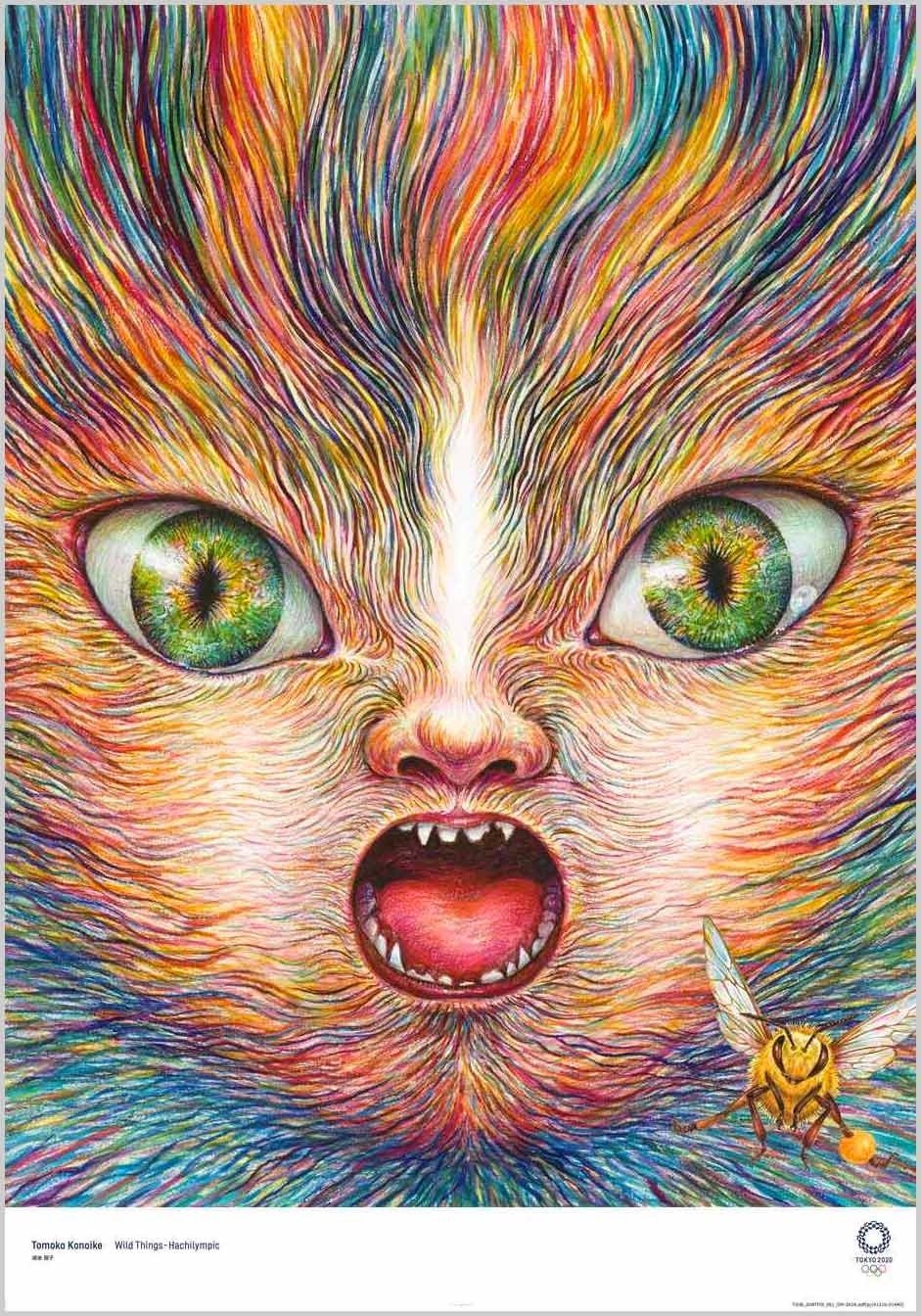

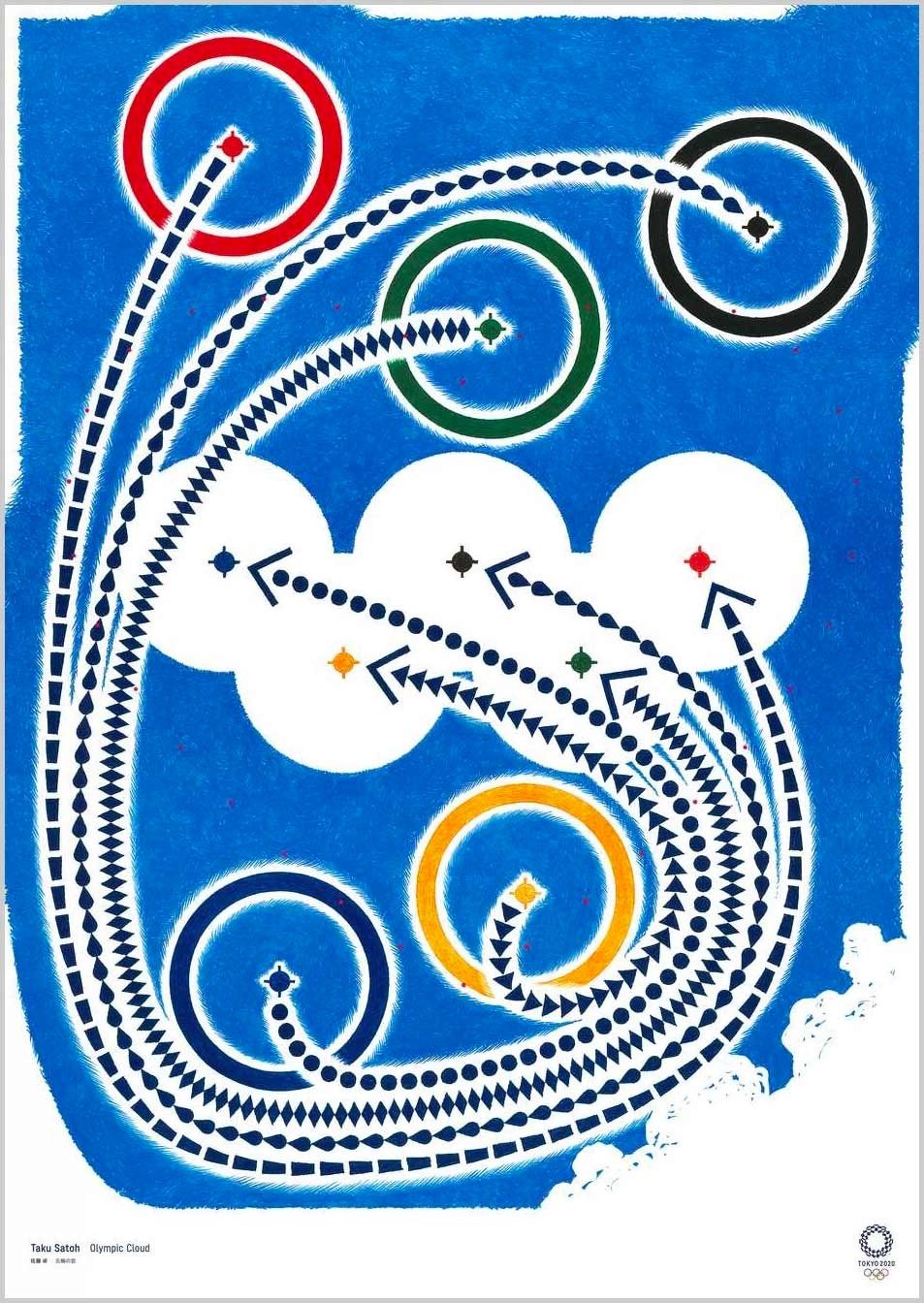

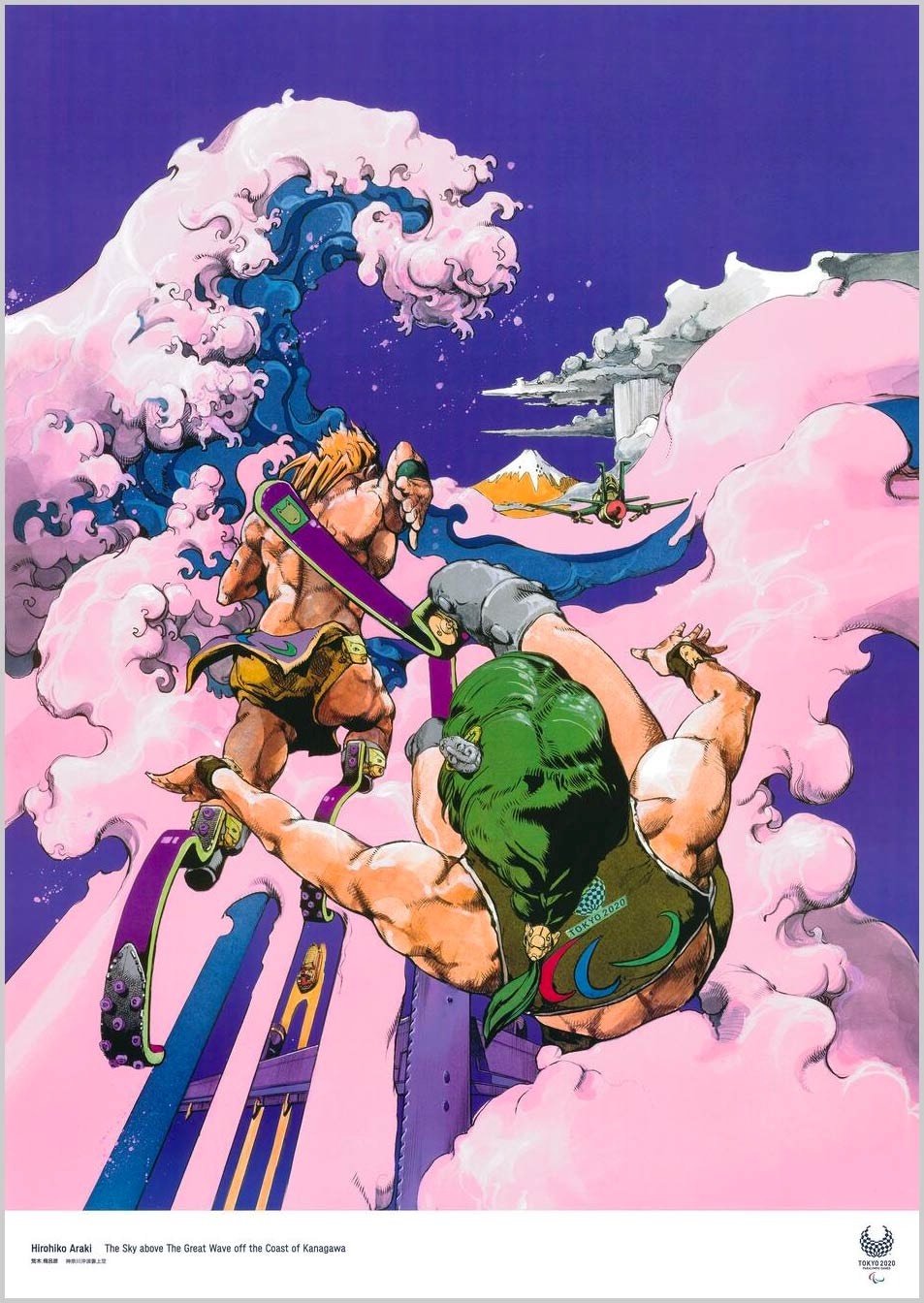

Wow, check out the official posters for the Tokyo 2020 Olympic and Paralympic Games.

What an amazing array of styles and disciplines — there’s manga, shodo (calligraphy), Cubism, photography, surrealism, and ukiyo-e. That stunning poster at the top is from Tomoko Konoike — fantastic. As you can see, posters from past Olympics have tended towards the literal, with more straightforward depictions of sports, the rings, stadiums, etc. Kudos to the organizers of the Tokyo Games for casting their net a little wider. Love it. (via sidebar)

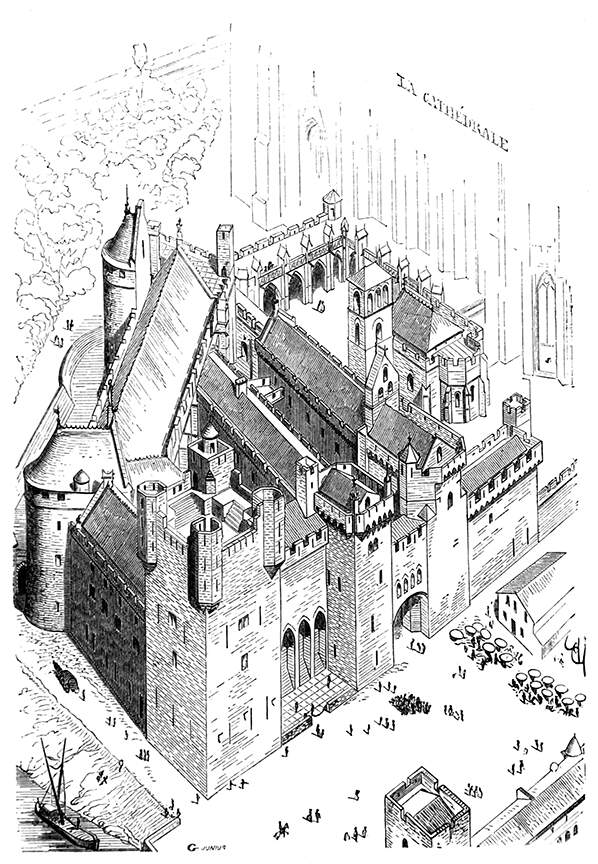

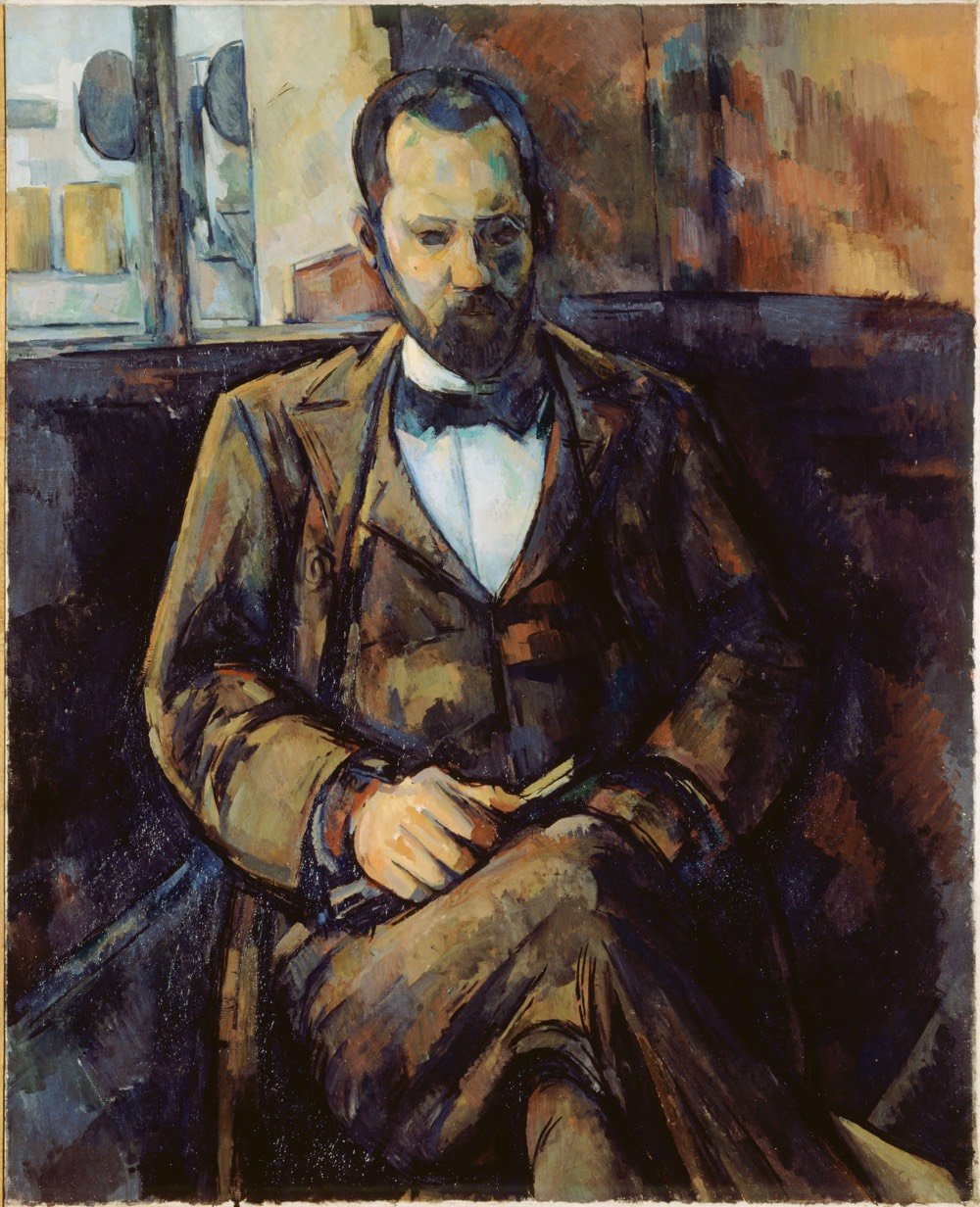

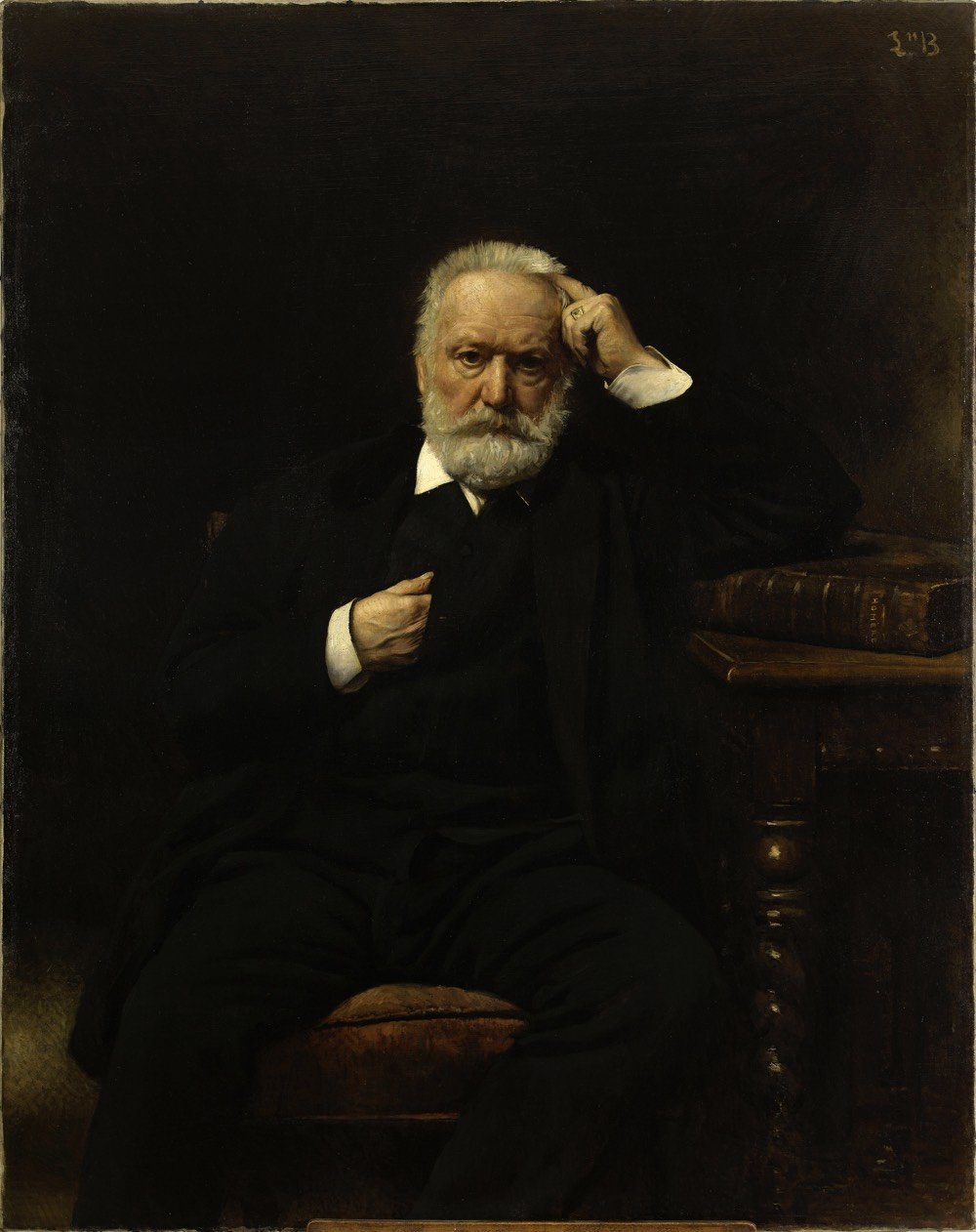

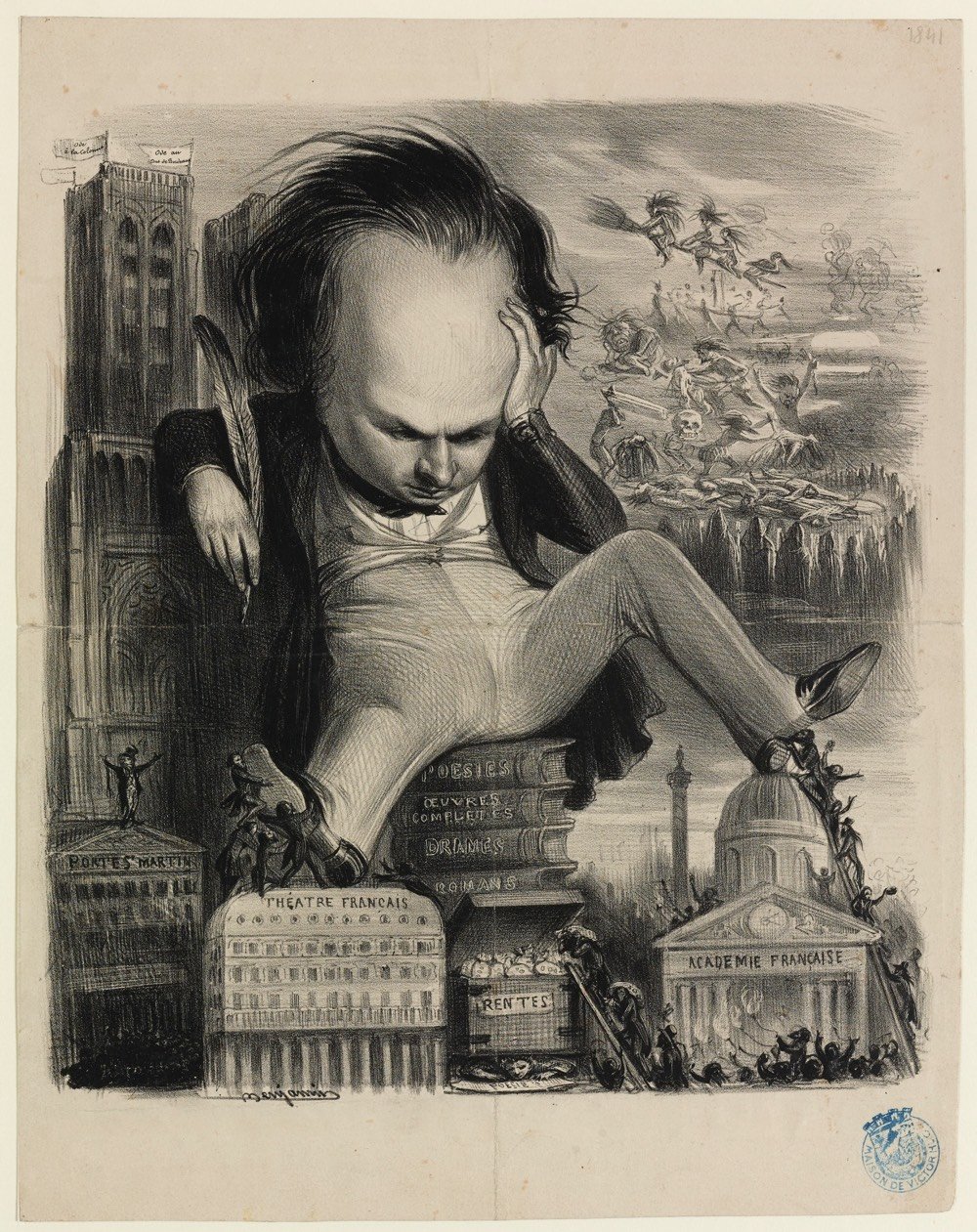

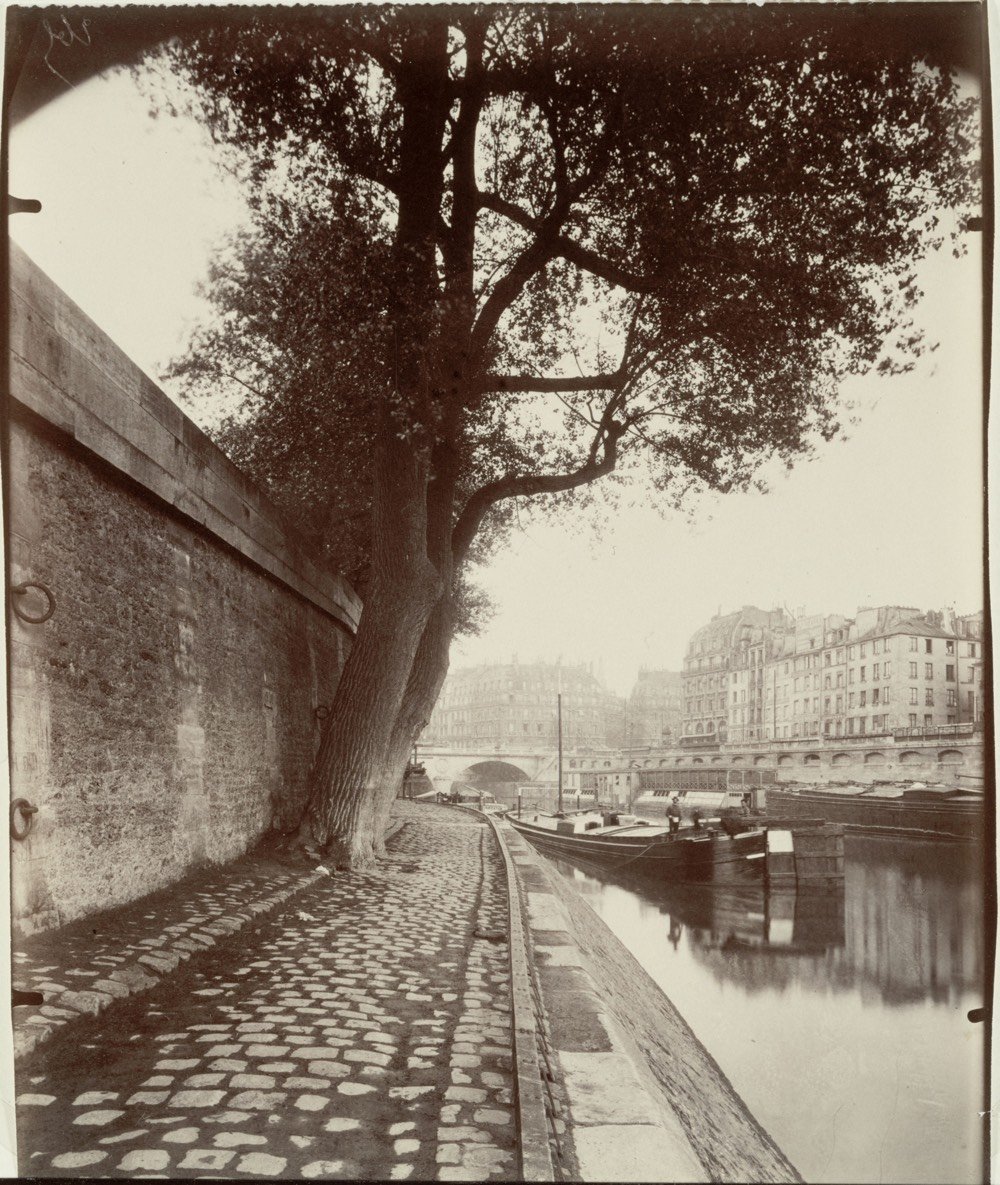

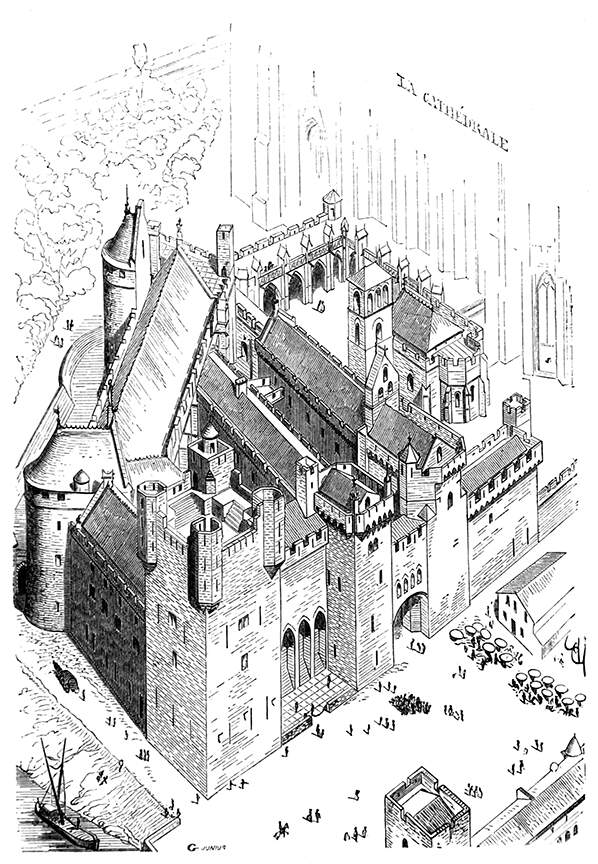

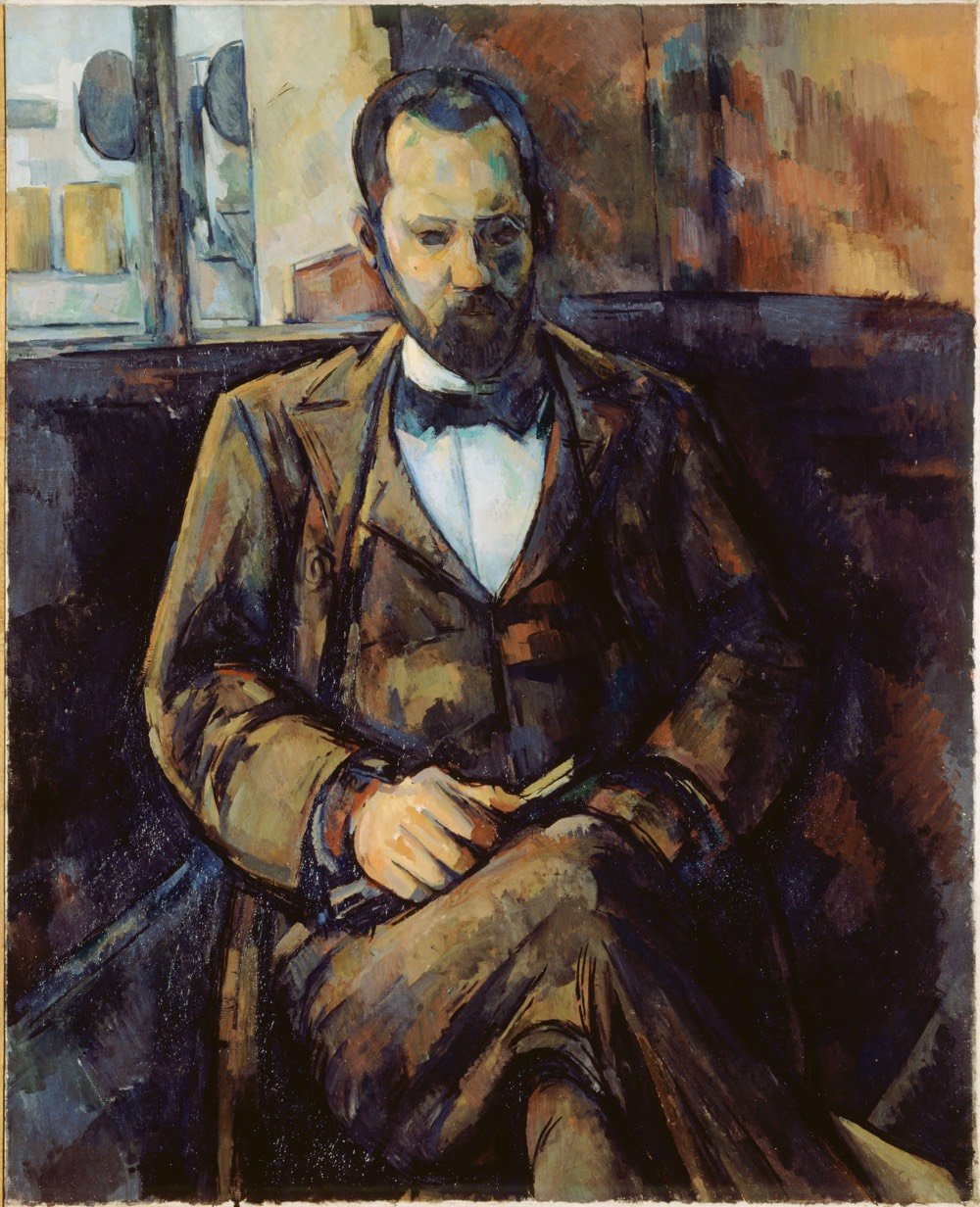

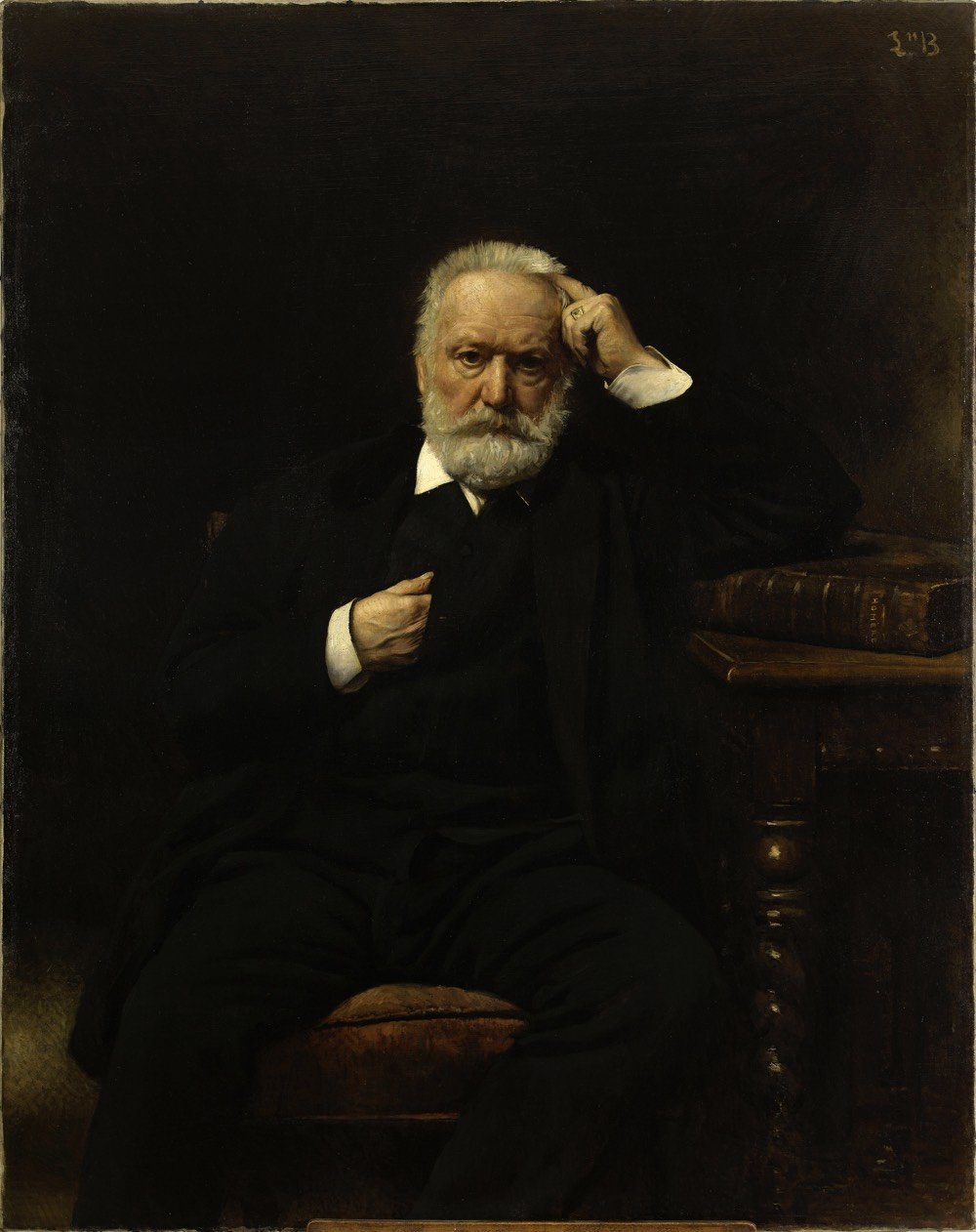

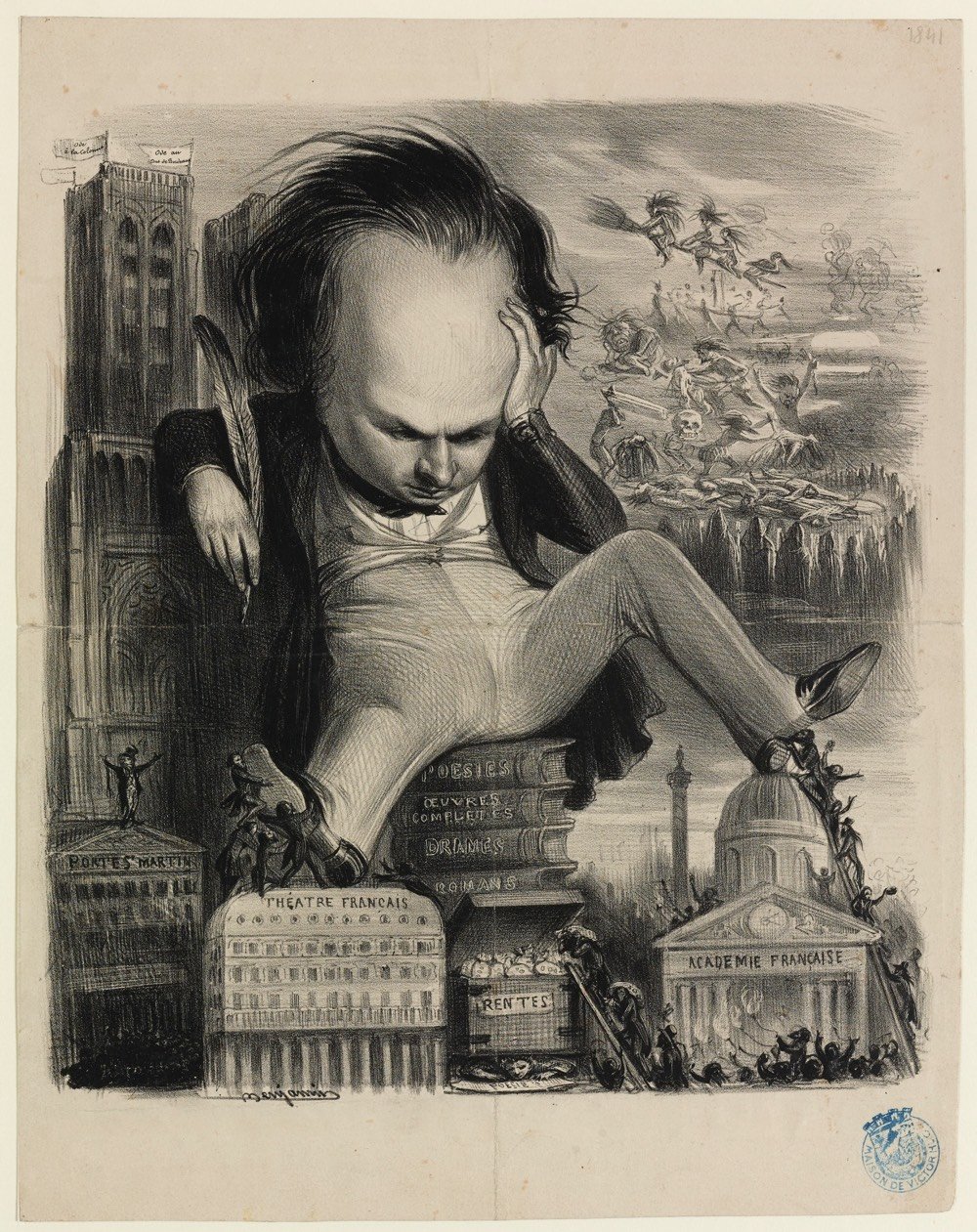

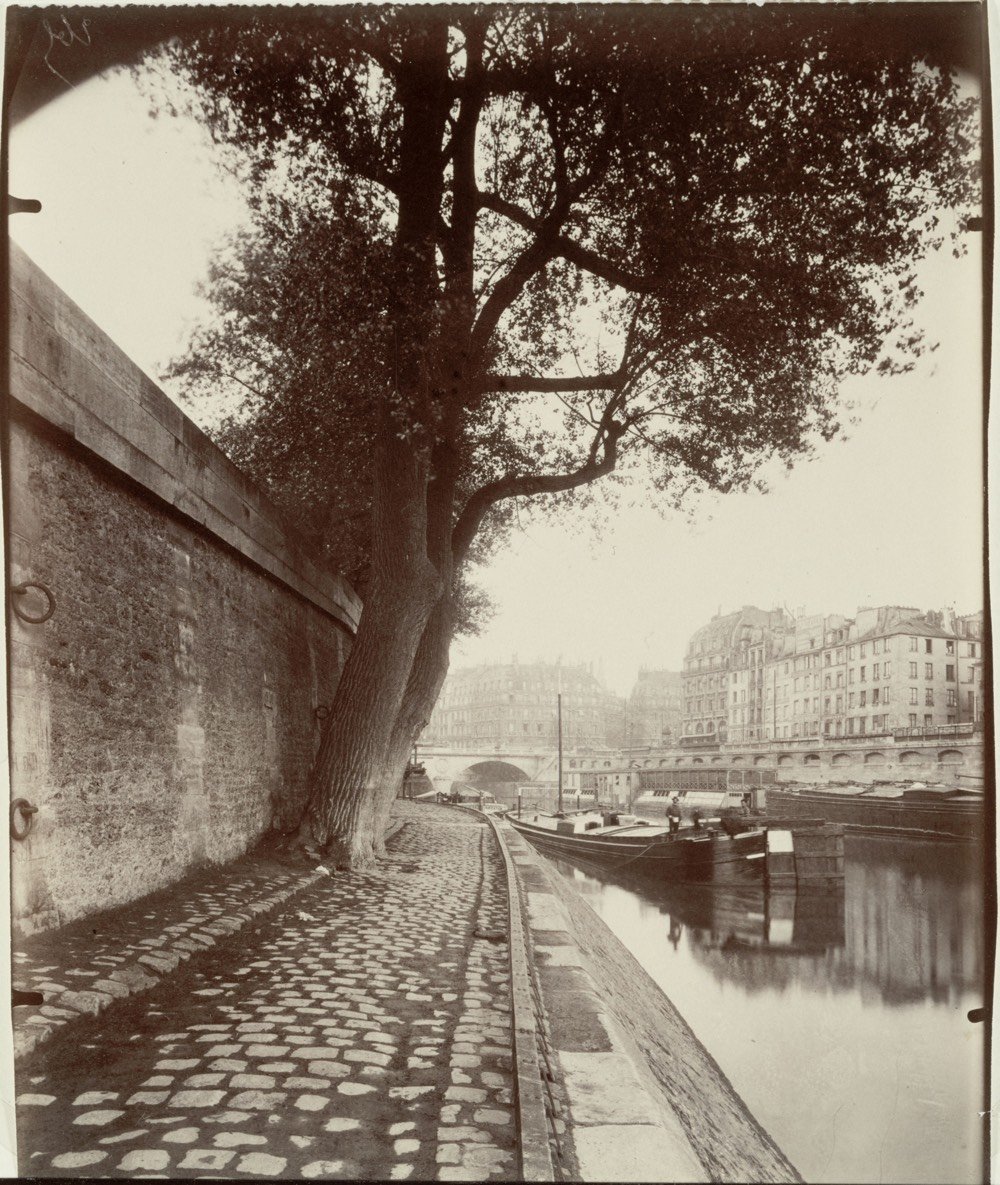

Paris Musées, a collection of 14 museums in Paris have recently made high-res digital copies of 100,000 artworks freely available to the public on their collections website. Artists with works in the archive include Rembrandt, Monet, Picasso, Cézanne, and thousands of others. From Hyperallergic:

Paris Musées is a public entity that oversees the 14 municipal museums of Paris, including the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, Petit Palais, and the Catacombs. Users can download a file that contains a high definition (300 DPI) image, a document with details about the selected work, and a guide of best practices for using and citing the sources of the image.

“Making this data available guarantees that our digital files can be freely accessed and reused by anyone or everyone, without any technical, legal or financial restraints, whether for commercial use or not,” reads a press release shared by Paris Musées.

What a treasure trove this is. I was particularly happy to see a bunch of work in here from Eugène Atget, chronicler of Parisian streets, architecture, and residents and one of my favorite photographers.

(via @john_overholt)

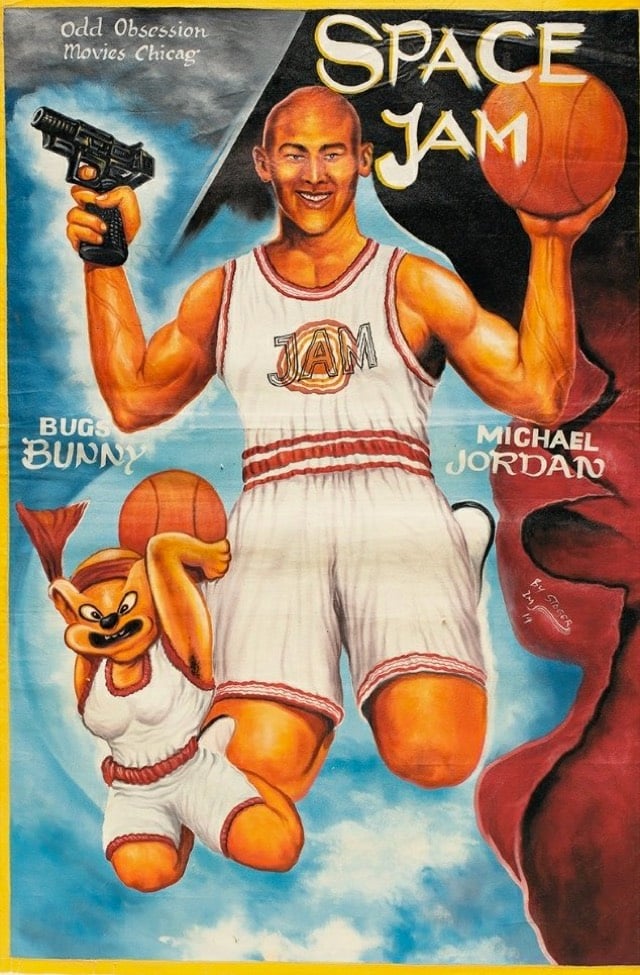

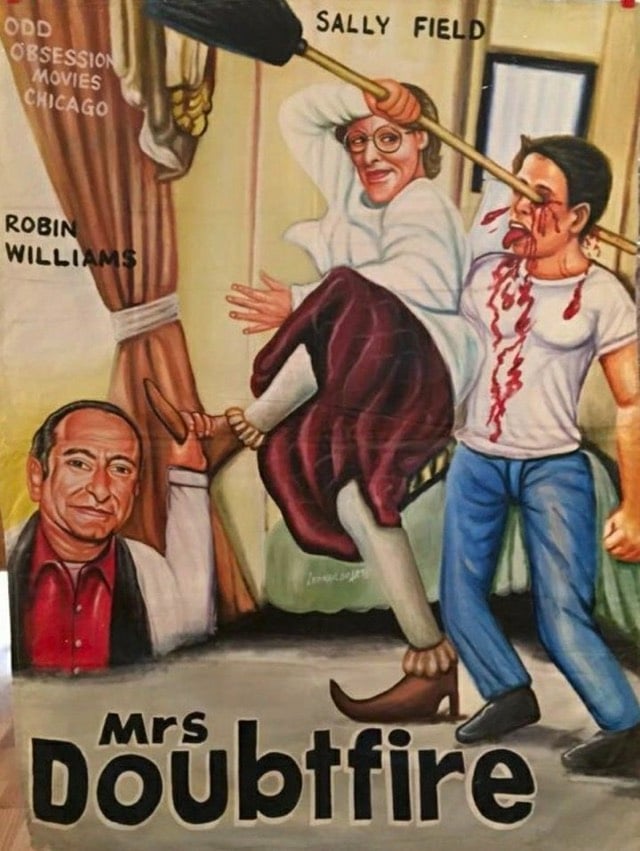

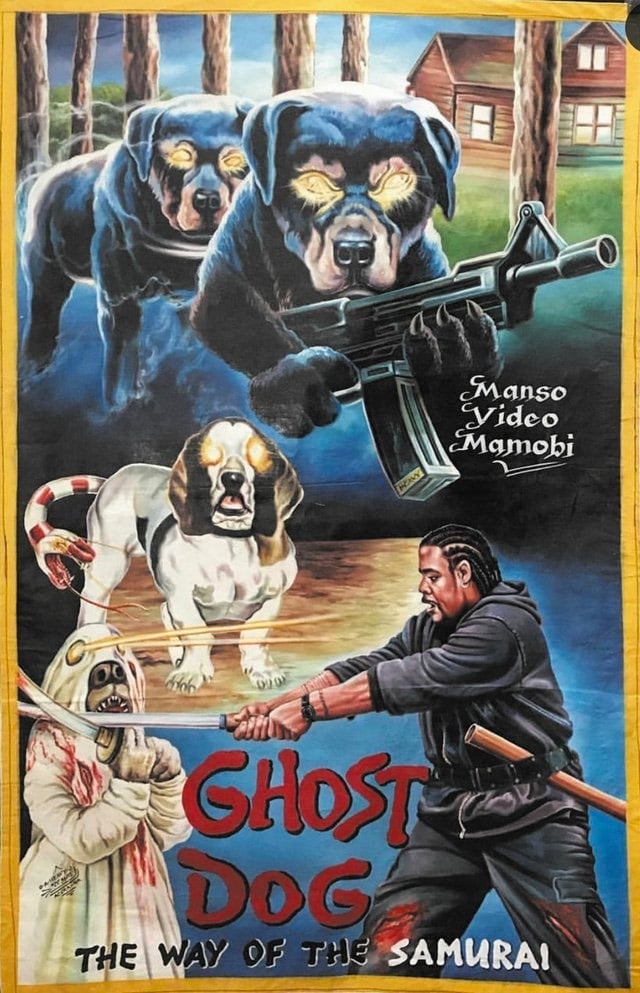

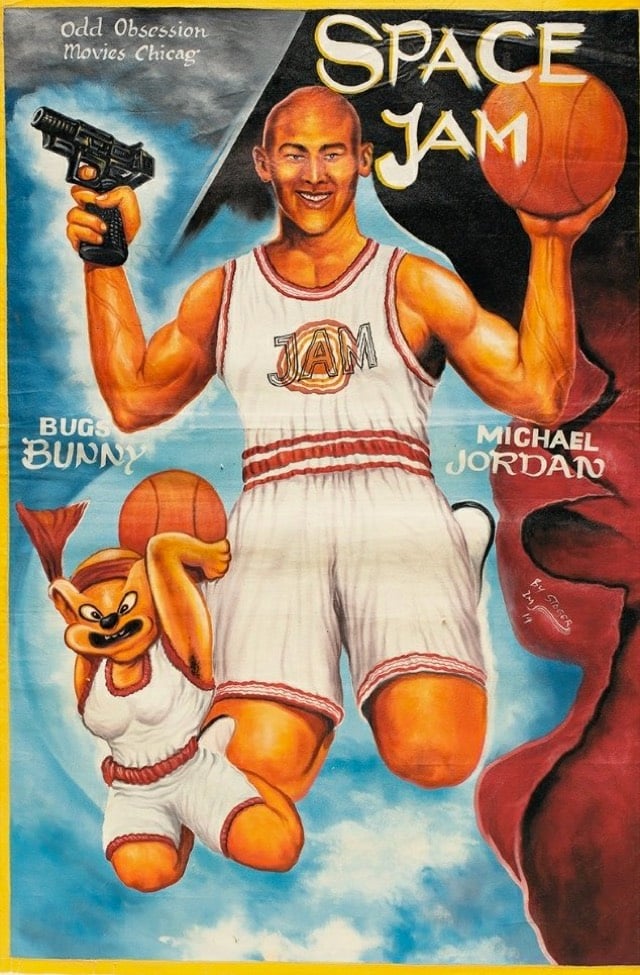

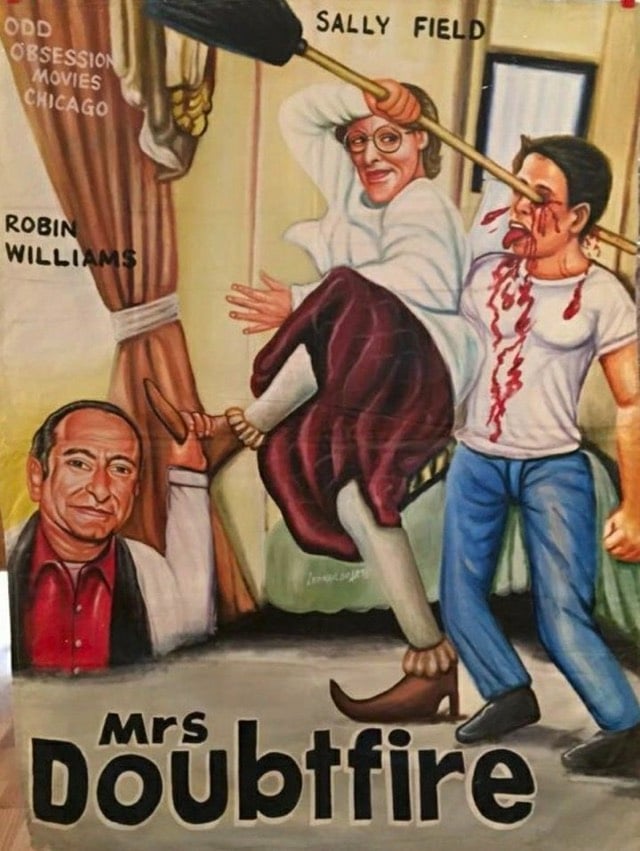

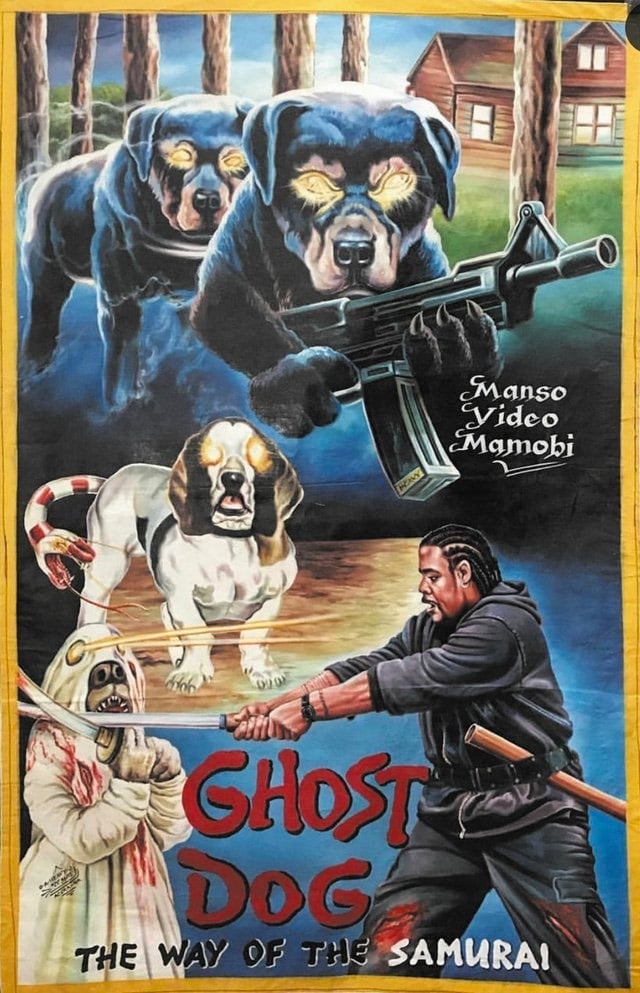

In order to drum up business for local movie theaters in Africa (most notably in Ghana), theater owners would commission local artists to paint movie posters.

When Frank Armah began painting posters for Ghanaian movie theaters in the mid-1980s, he was given a clear mandate: Sell as many tickets as possible. If the movie was gory, the poster should be gorier (skulls, blood, skulls dripping blood). If it was sexy, make the poster sexier (breasts, lots of them, ideally at least watermelon-sized). And when in doubt, throw in a fish. Or don’t you remember the human-sized red fish lunging for James Bond in The Spy Who Loved Me?

“The goal was to get people excited, curious, to make them want to see more,” he says. And if the movie they saw ended up surprisingly light on man-eating fish and giant breasts? So be it. “Often we hadn’t even seen the movies, so these posters were based on our imaginations,” he says. “Sometimes the poster ended up speaking louder than the movie.”

You can check out more of these amazing artworks in this Twitter thread, this BBC story, on the AIGA site, and at Poster House, which has an exhibition of these posters up through Feb 16.

Update: I removed this modern-day spoof of the Ghanaian posters from the post. The tell is the reference to this amazing GIF. (thx, erik)

Inspired by a trip to Venice, the world’s most prominent example of what life could be like in many of our coastal cities in the years to come, Hayden Williams made a series of 3D rendered images showing what our world might look like underwater. (via the morning news)

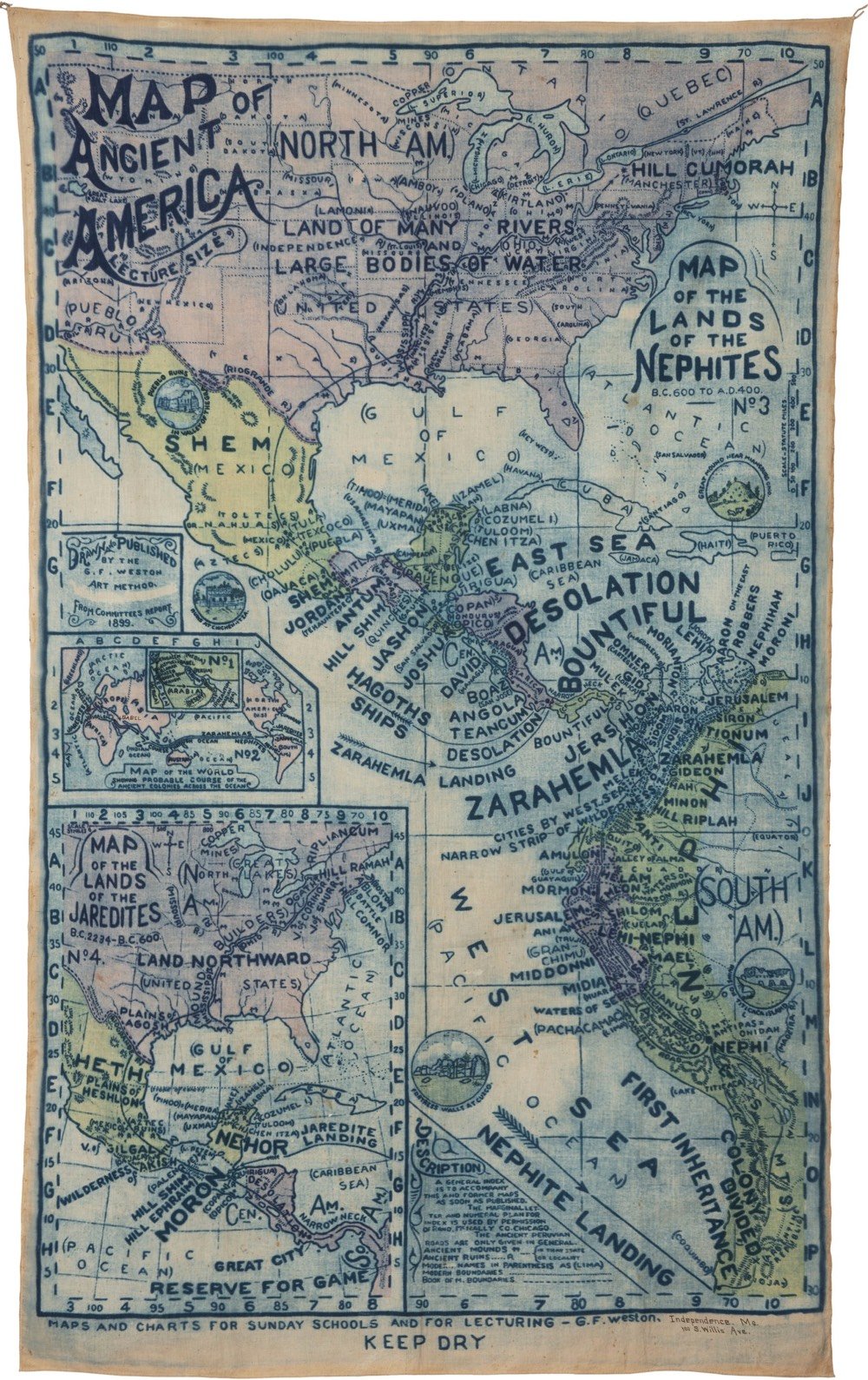

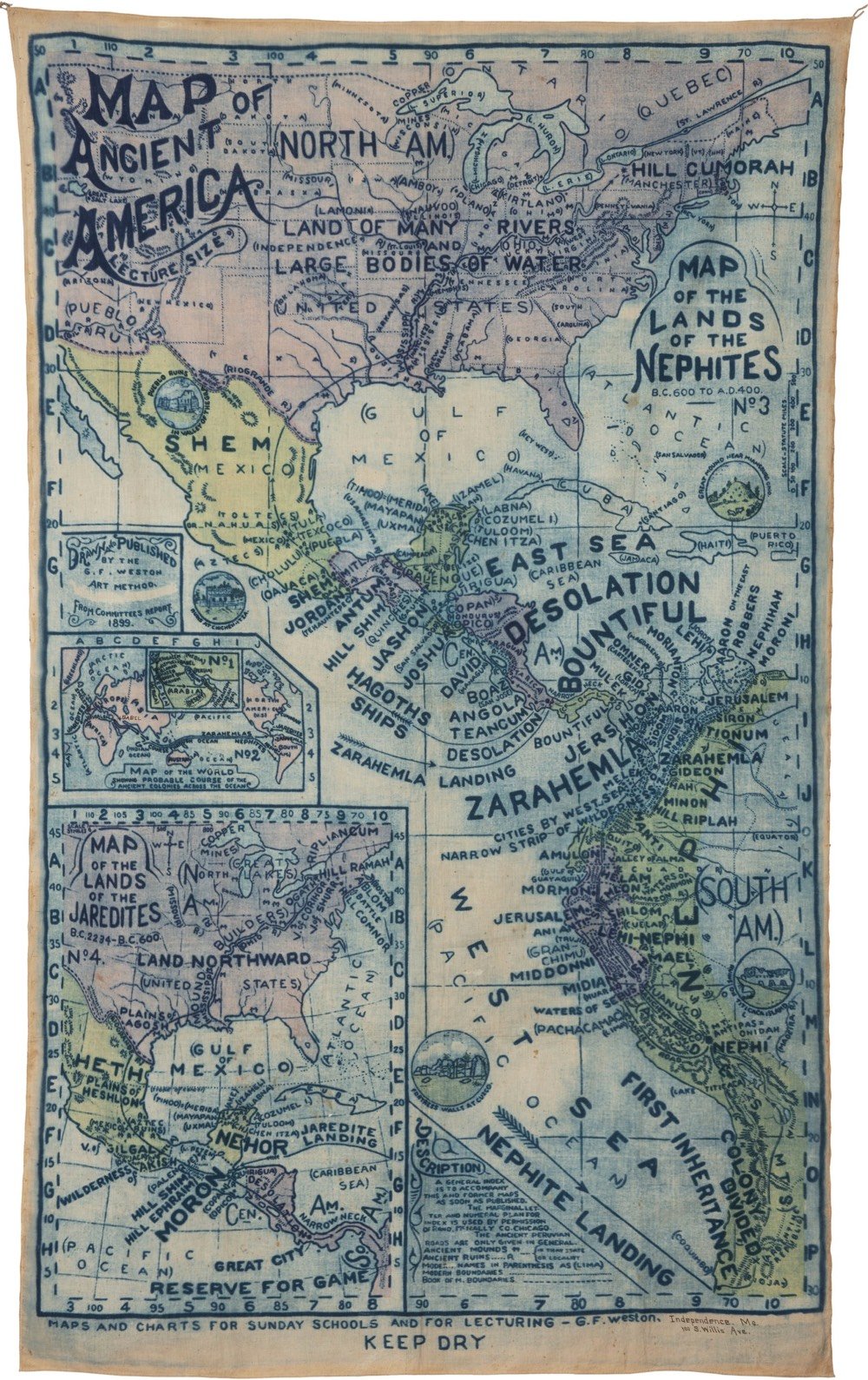

Boston Rare Maps recently sold a nine-foot-high cloth map from 1899 that shows a geographic interpretation of the Book of Mormon.

The map was an official production of the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints (RLDS) in Independence, Missouri. The RLDS (known since 2001 as the Community of Christ), is a reformist branch of the Church of Latter Day Saints, established in 1860.

You can read more about the proposed setting of the Book of Mormon on Wikipedia and its adherents’ belief that the indigenous peoples of the Americas are descended from Israelites.

The Book of Mormon is based on the premise that two families of Israelites escaped from Israel shortly before the sacking of Jerusalem by Nebuchadnezzar and that they constructed a ship, sailed across the ocean, and arrived in the New World as founders of Native American tribes and eventually the Polynesians. Adherents believe the two founding tribes were called Nephites and Lamanites, that the Nephites were white and practiced Christianity, and that the Lamanites were rebellious and received dark skin from God as a mark to separate the two tribes. Eventually the Lamanites wiped out the Nephites around 400 AD, leaving only dark skinned Native Americans. The descent of Native Americans from Israel is a key part of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints’s foundational beliefs.

(via @john_overholt)

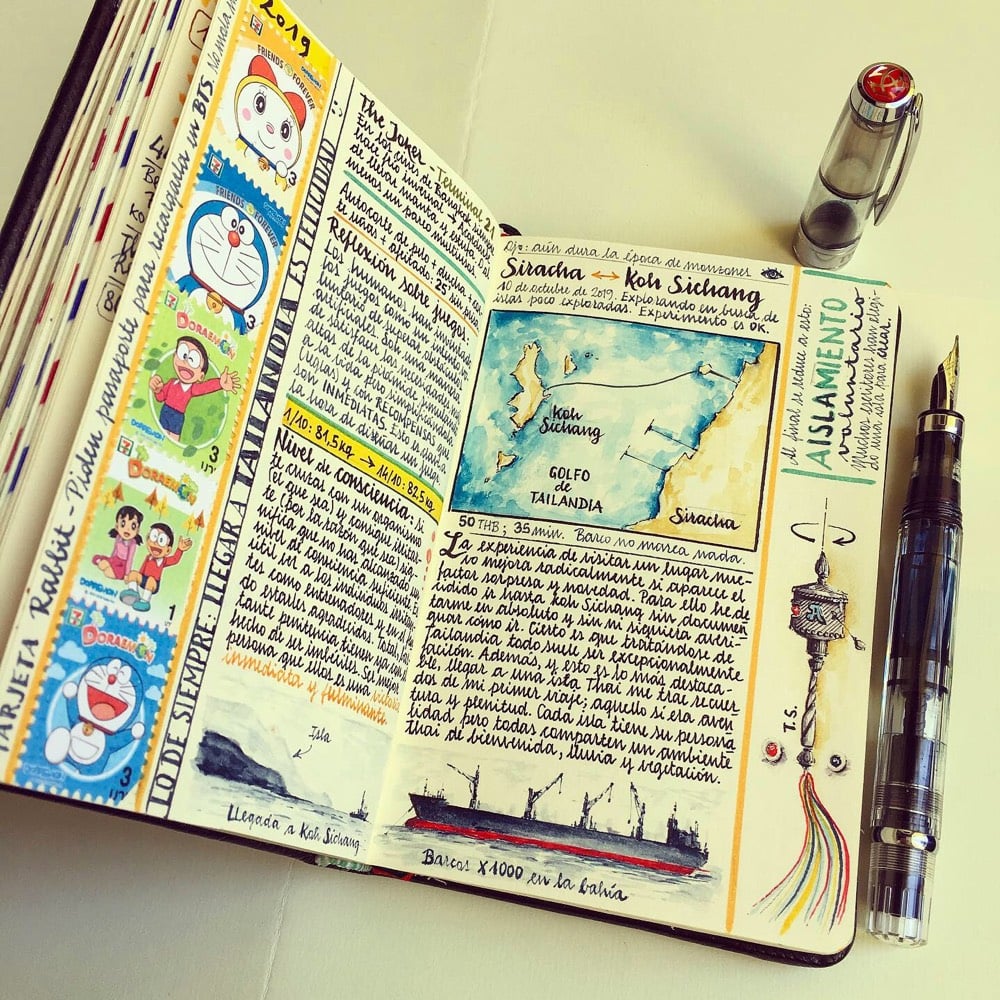

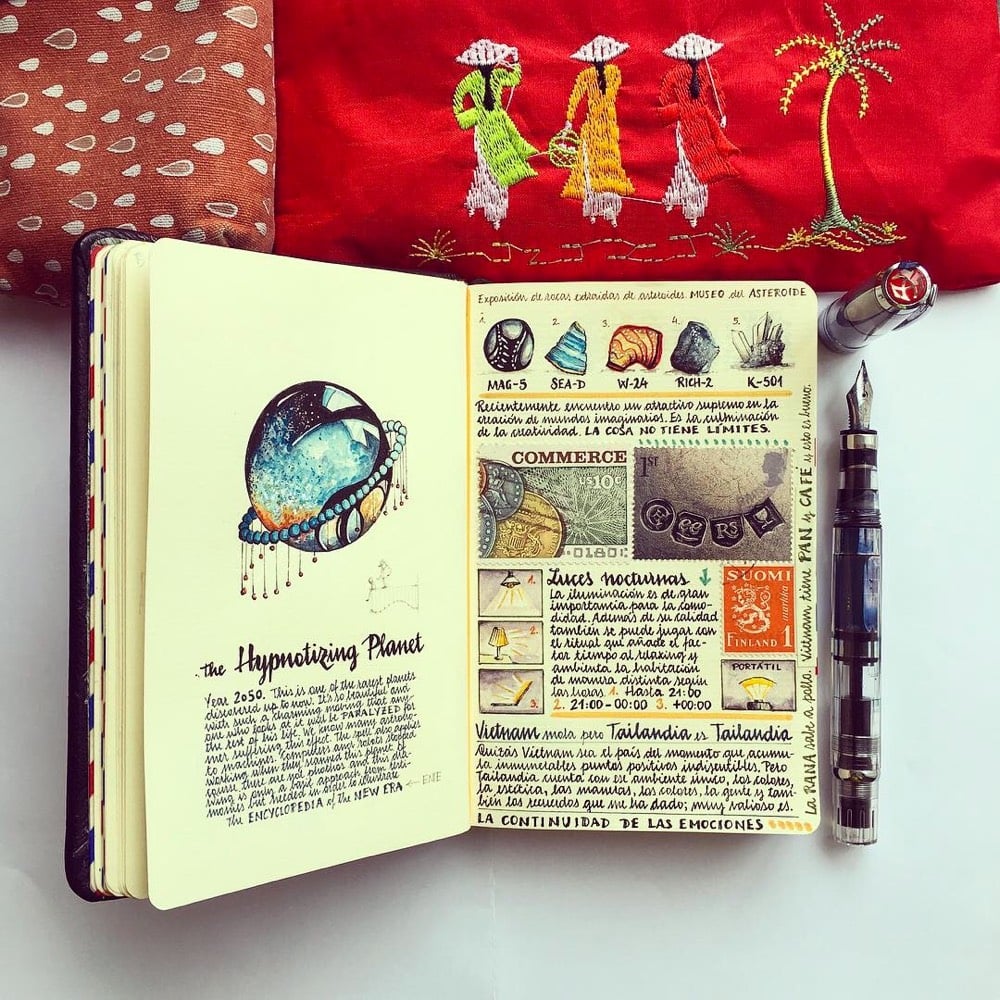

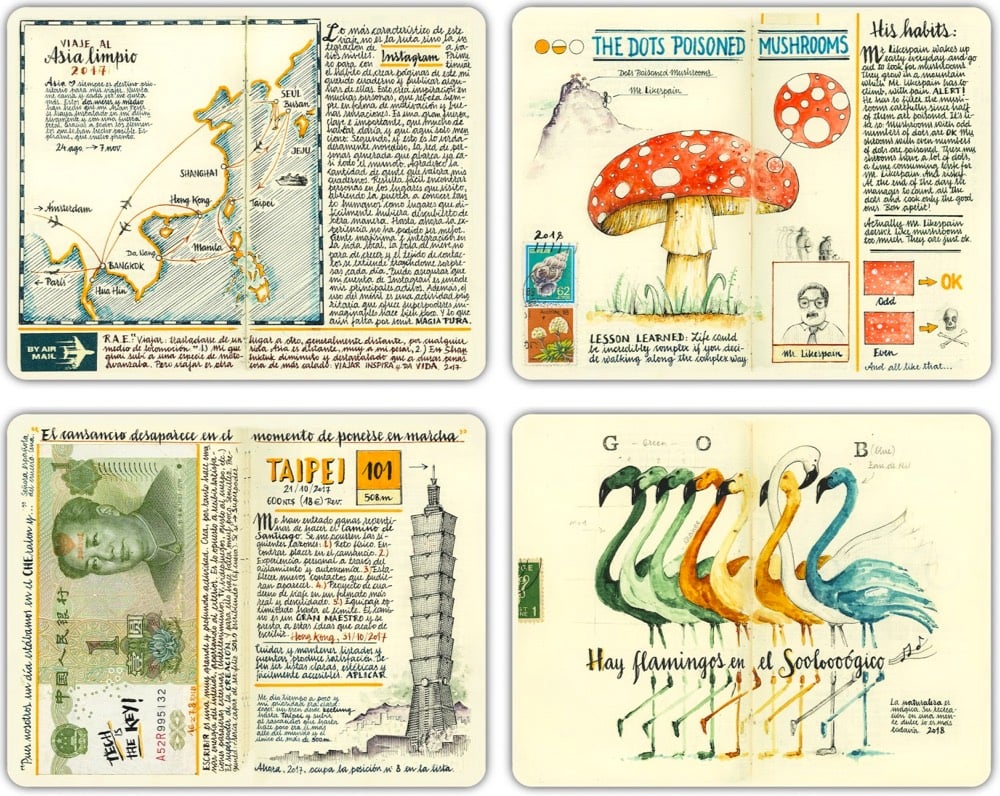

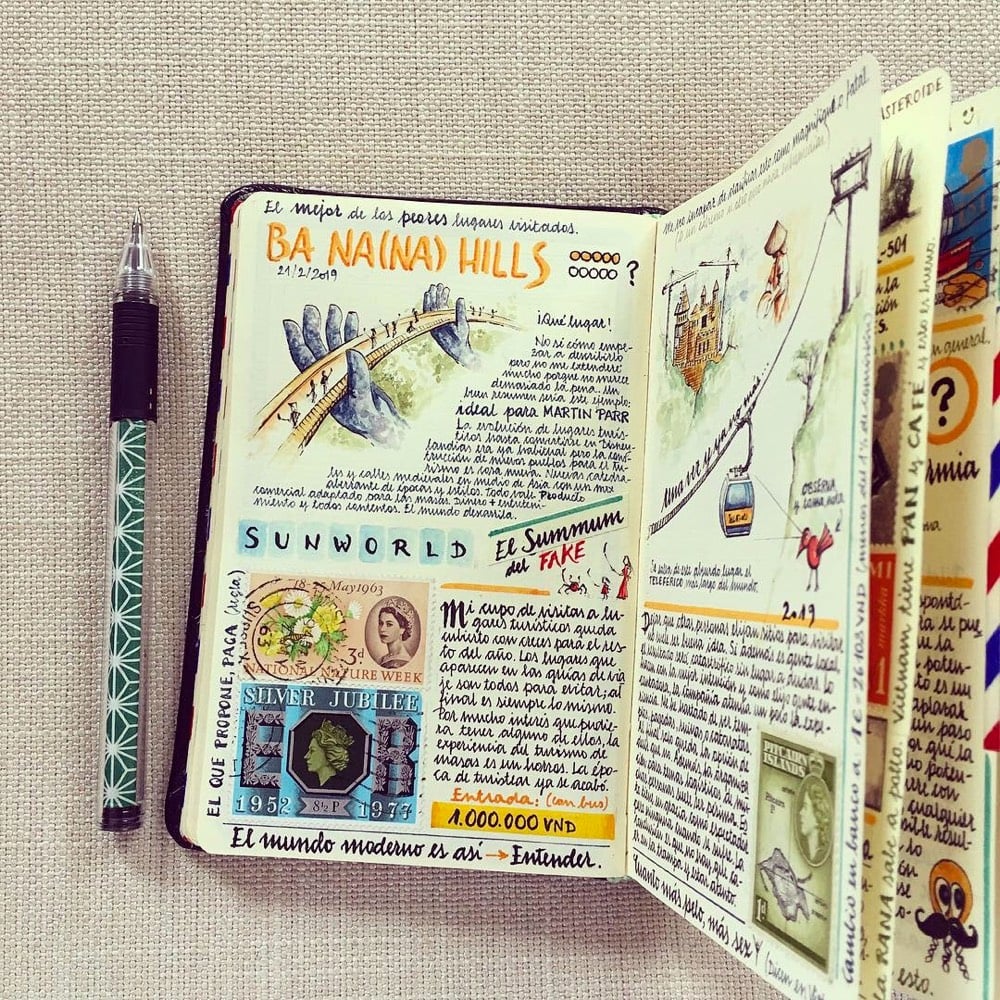

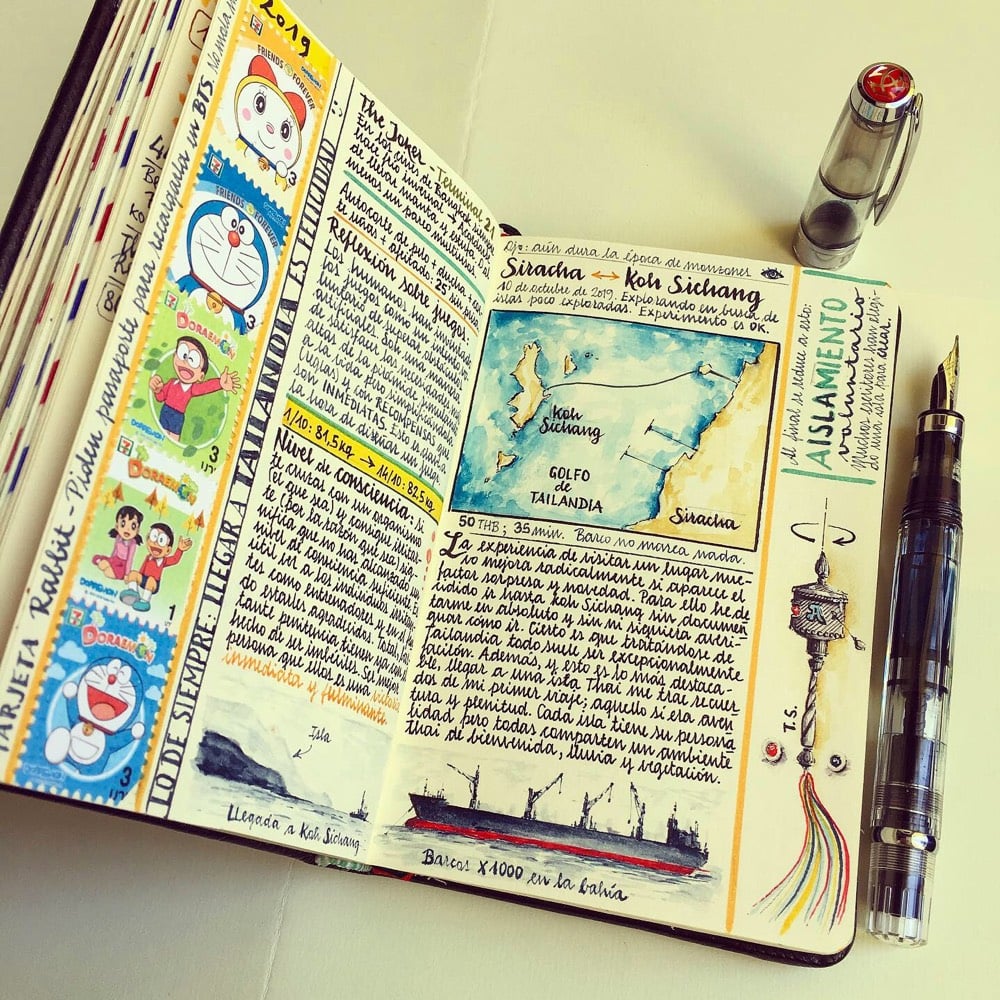

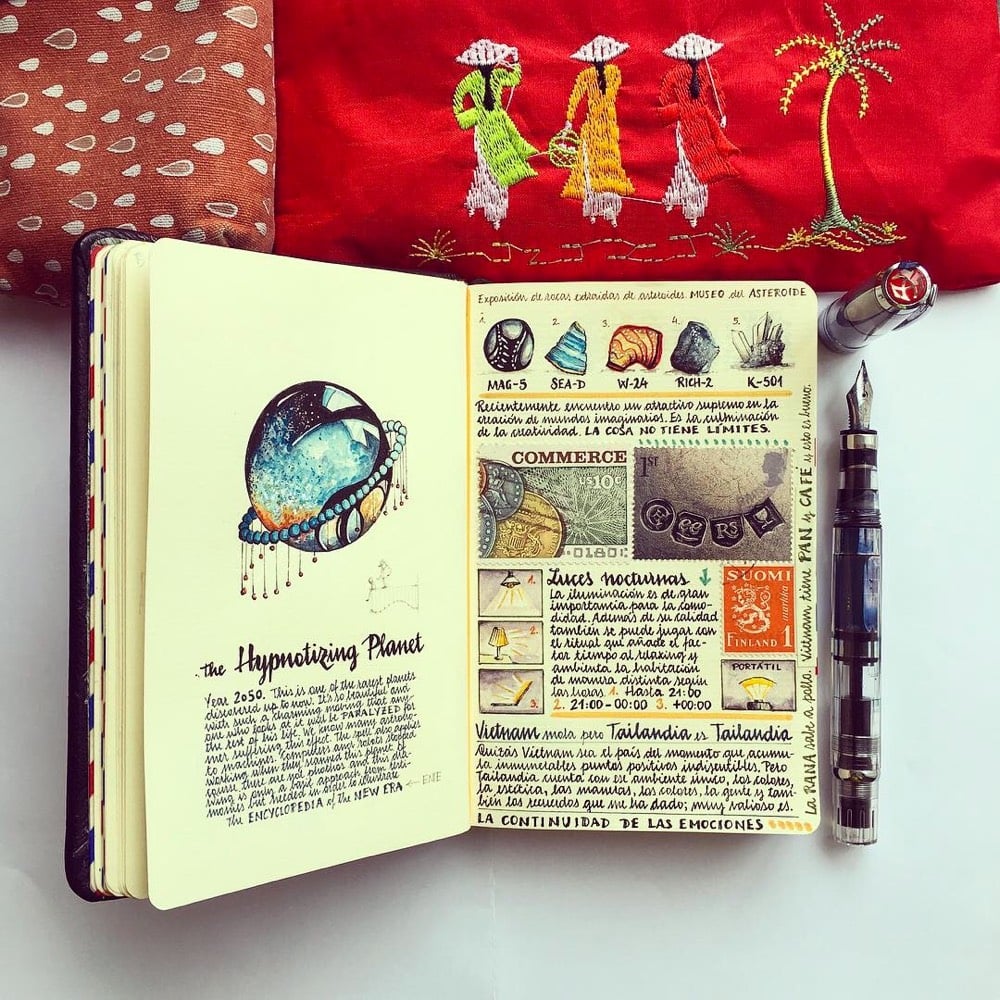

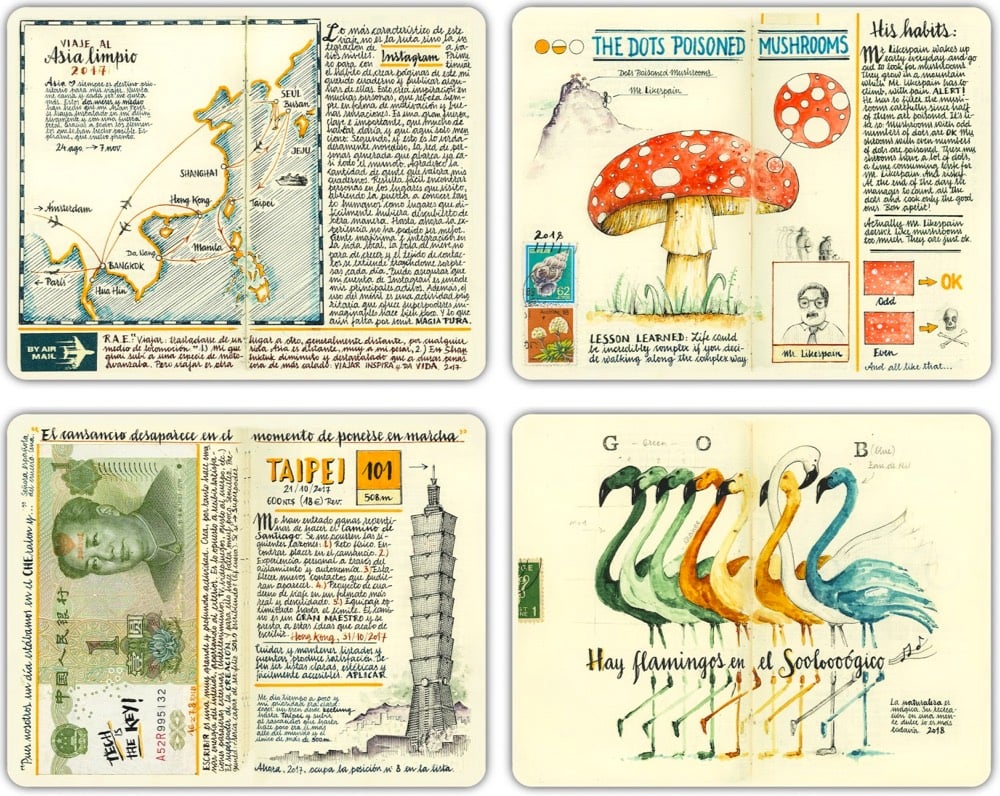

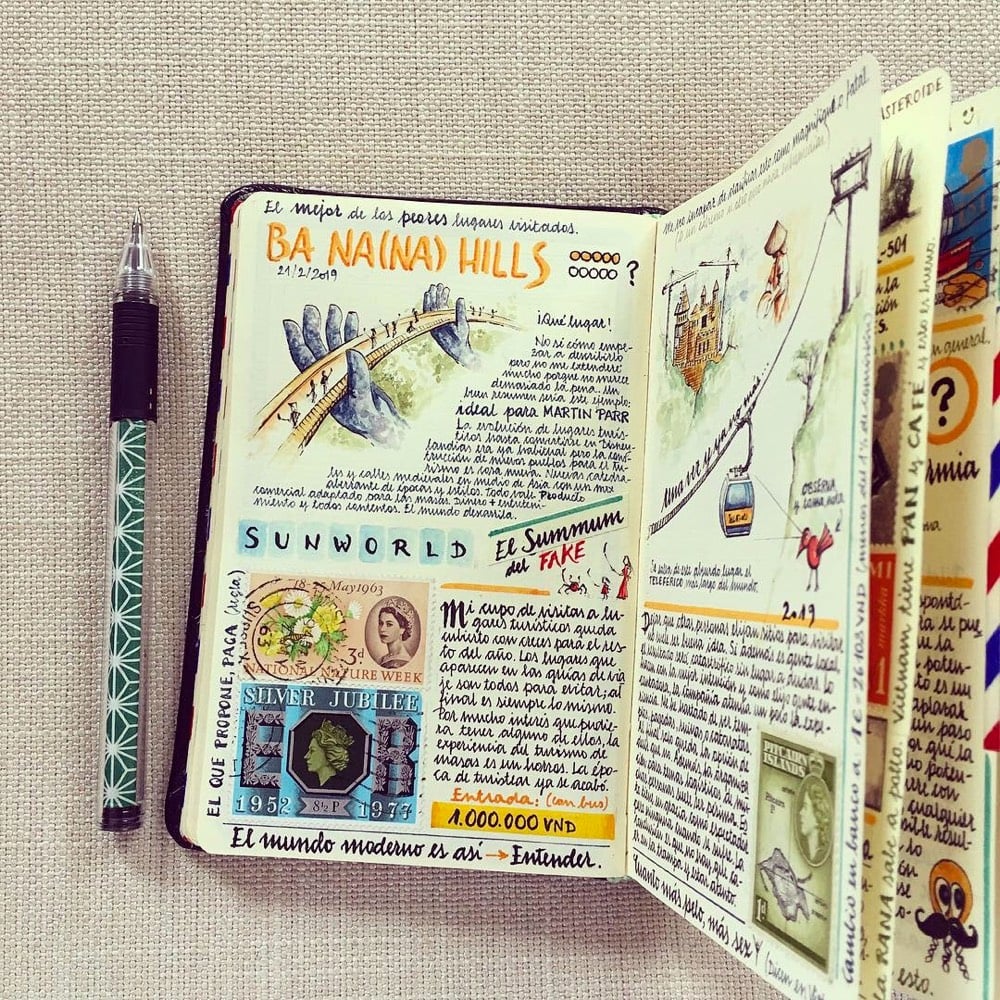

Good God, these hand-drawn & painted notebooks by José Naranja documenting his travels are fantastic! From Colossal:

Formerly an aeronautic engineer, Naranja now archives his thoughts while visiting foreign countries by hand-crafting journals replete with items like collected stamps, an illustration of the periodic table, and a study of fountain pens. Each mixed-media page centers on a theme, such as the culture surrounding eating a bowl of ramen or the flamingos found in a zoo.

Whenever I see something like this, it makes me want to learn how to draw/paint better than my current 4th grade level.1 I spent about 45 minutes poring over his work just now. So creative & exacting…look at that handwriting! And check out the tiny box of watercolors he carries with him.

You can keep up with Naranja’s latest adventures on his blog or on Instagram. If you’d like to buy some of his art — including a bound copy of some of his notebooks — there’s a small shop. (via colossal, which is also endlessly creative & meticulous)

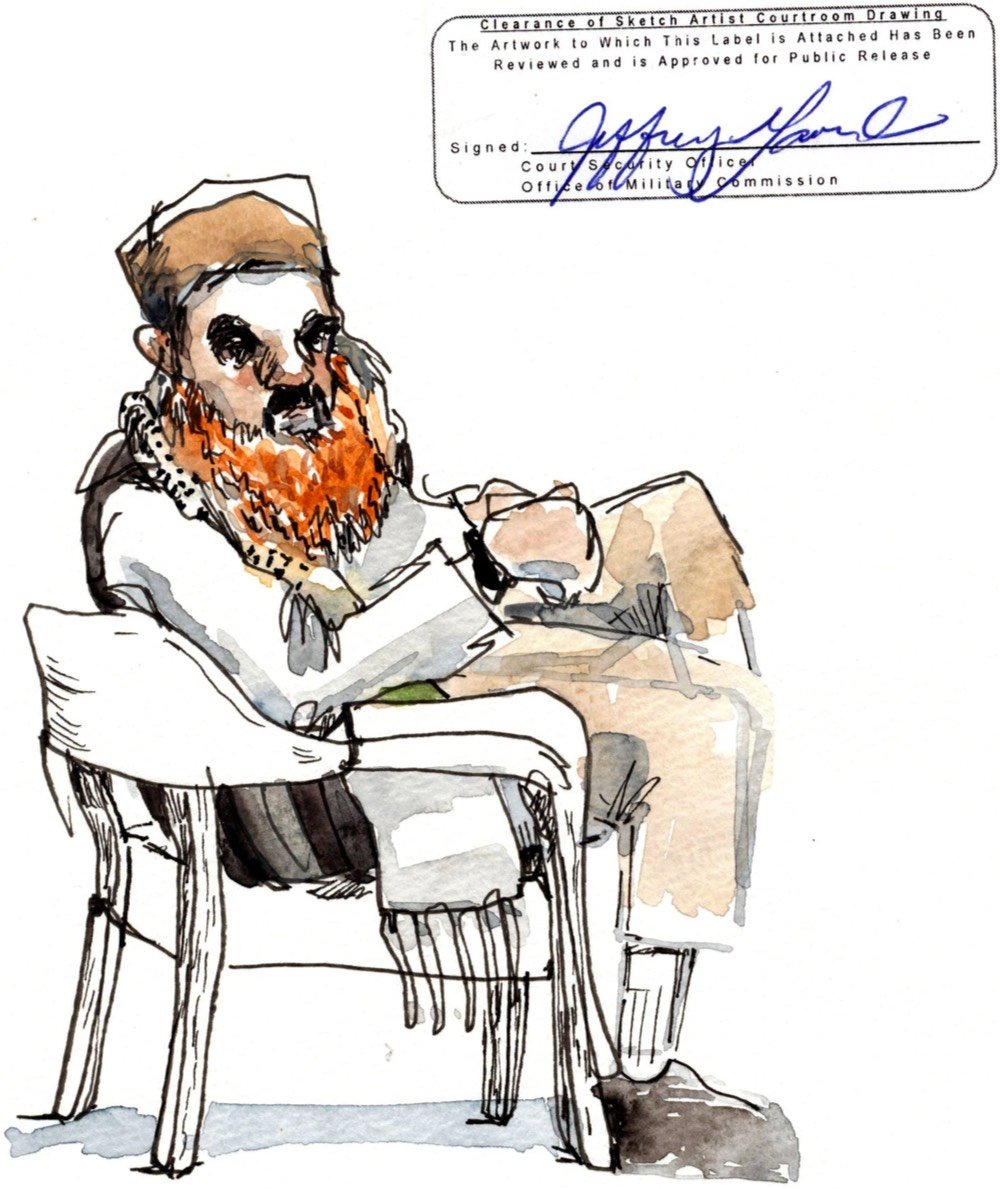

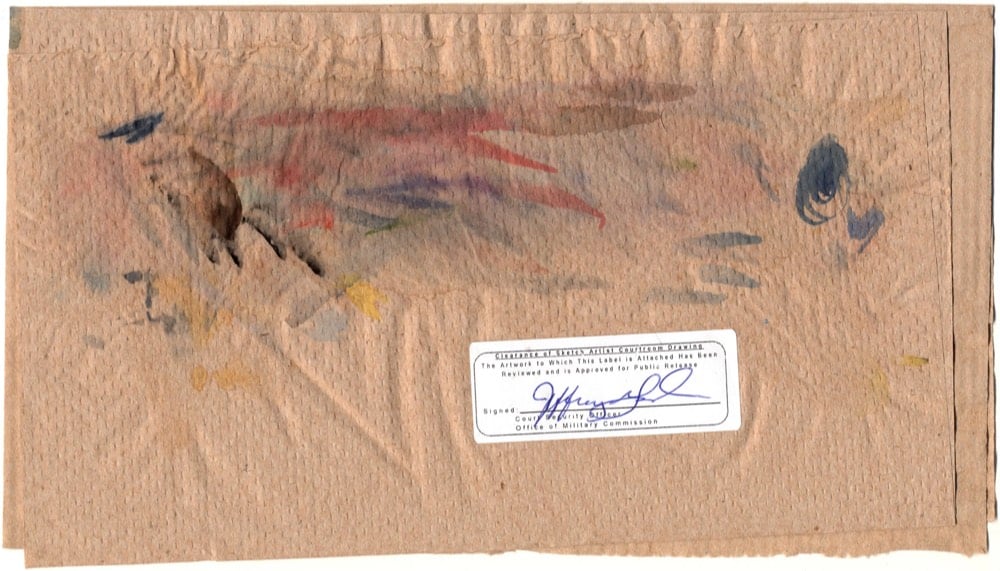

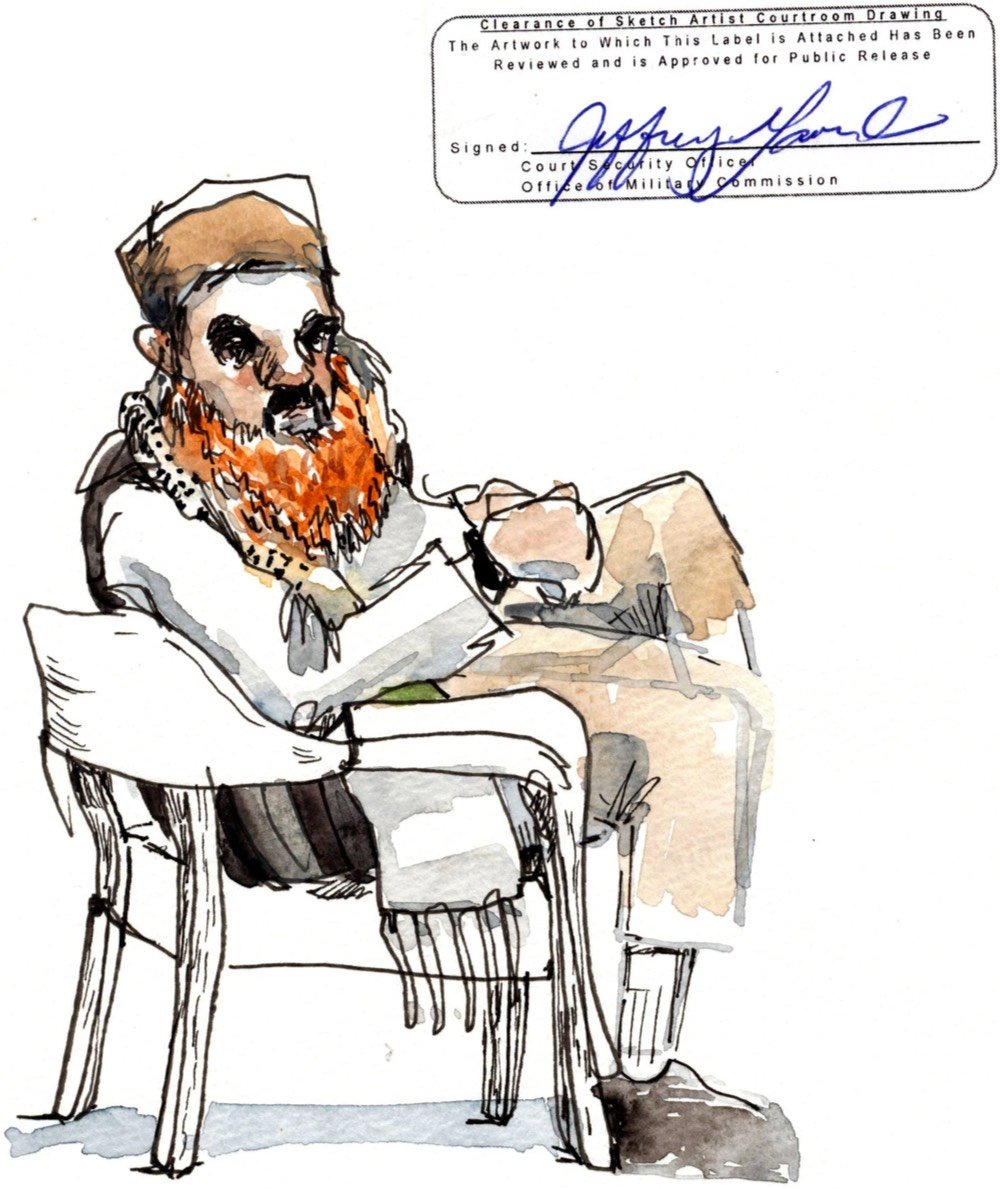

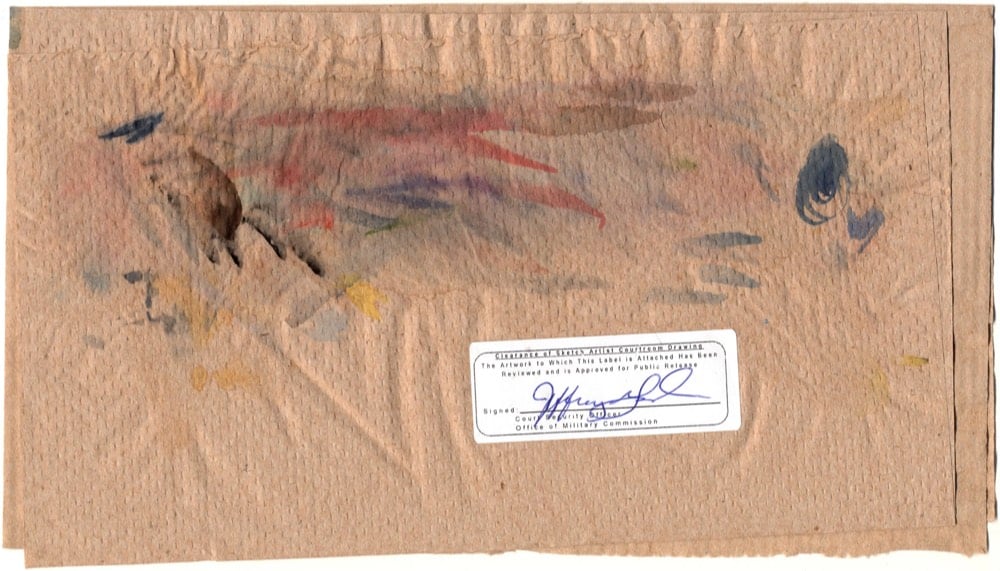

Illustrator Wendy MacNaughton spent a week at Guantánamo Bay sketching the proceedings at the 9/11 military court for this NY Times piece. In a behind-the-scenes piece, MacNaughton describes how she made the drawings, including the creative challenge posed by the restrictions and censorship enforced by US military officials.

Of the 30-something drawings I presented, Mr. Lavender shook his head at only two. The first contained some classified items in the courtroom. That made sense. The second was a handwritten list of everything that I was not allowed to draw, which I’d made to use as a reminder while working. I wanted to keep it. He refused.

I argued that the information it contained had been disclosed elsewhere. But Mr. Lavender and his supervisor came to the conclusion that my handwritten list was indeed a drawing, technically containing things I couldn’t draw. My “No” list was a no-go.

That’s Guantánamo.

Every drawing she made needed a signed approval sticker from the court’s censor, and in this piece and on Instagram, MacNaughton didn’t photoshop the sticker out, reinforcing that the censorship is a vital part of the story she’s trying to tell. Even the paper towel she used to clean her paint brushes needed a sticker:

Move over, every other craft project — this Homer Simpson disappears into the bushes embroidery piece by Rayna of Hermit Girl Creations is the best embroidery in the history of the world. The scene is taken from a 1994 episode of The Simpsons called Homer Loves Flanders and has become a bit of a meme in recent years; here’s the clip:

Check out her Instagram or Etsy shop — she does a lot of other Simpsons-based embroidery as well as Charlie Brown, The Office, Dr. Seuss, Frog & Toad, Stranger Things, and Futurama. Looks like she takes commissions via Instagram DM.

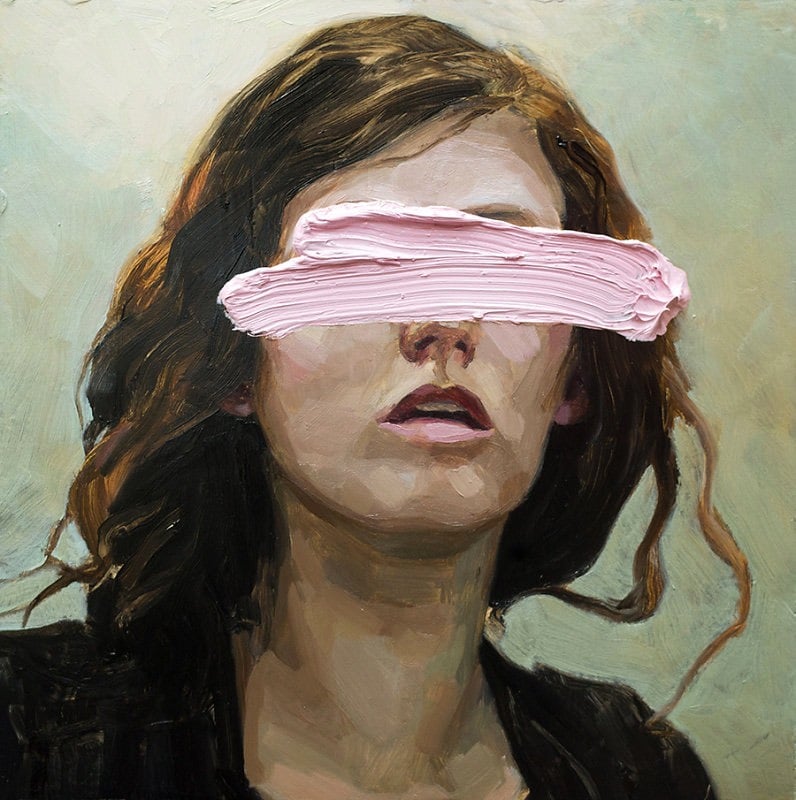

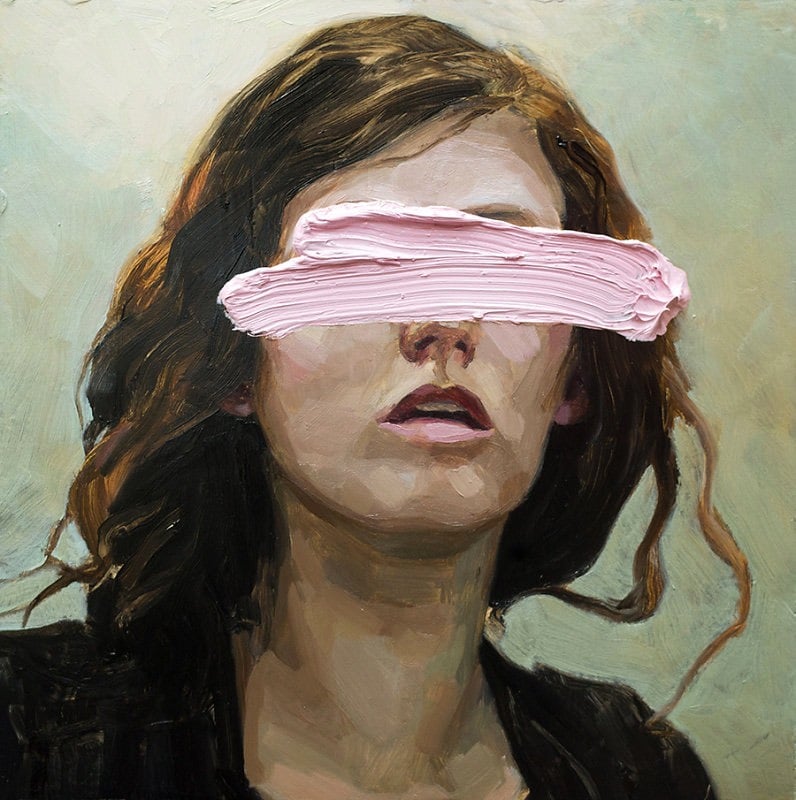

Hélène Delmaire paints portraits of girls without eyes.

Delmaire did all of the paintings for the film Portrait of a Lady On Fire and even appears painting in the film.

I did pretty much all the paintings except the one that’s without a face. Céline and the actresses would work out how the scene was going to go. Once that was set up, I’d come, take a photo and while they were shooting the scenes, I went to a little corner of the castle and did my sketches.

Delmaire sells originals and prints of her work here. (via @alteredq)

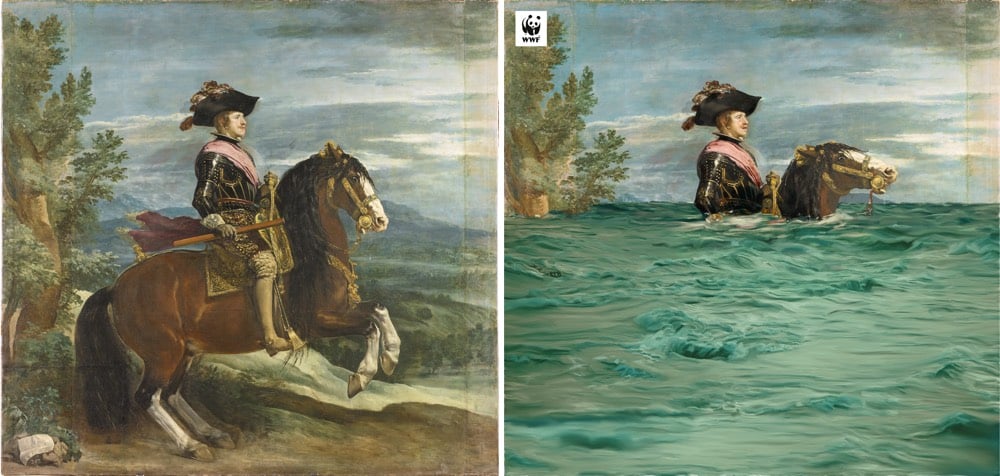

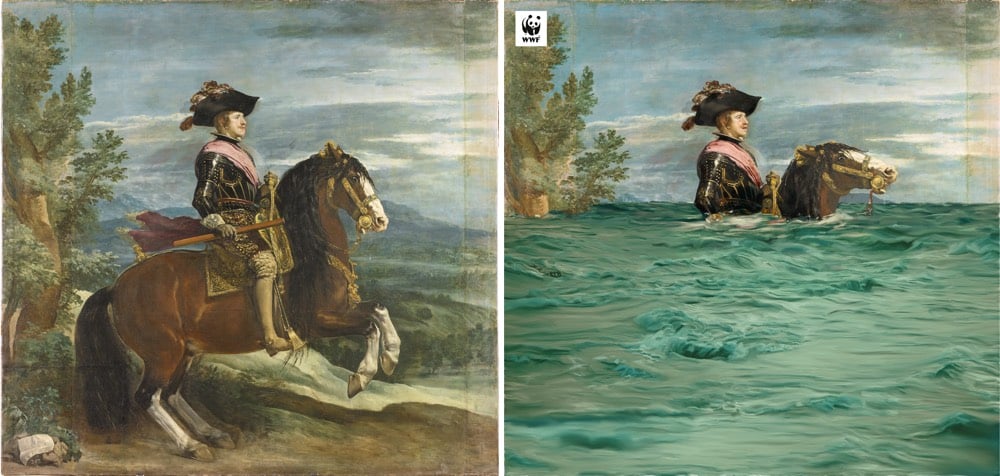

In collaboration with the Prado Museum in Madrid, the World Wildlife Fund altered a few paintings from the museum’s collection to highlight the future effects of climate change: extinction of species, sea level rise, desertification, and climate refugees.

(via open culture)

A team of archaeologists has found a massive painting in a cave in Indonesia that uranium dating analysis shows to be around 43,900 years old, which they say is “currently the oldest pictorial record of storytelling and the earliest figurative artwork in the world”.

Cave painting was assumed to have originated in Europe, but these Indonesian paintings are thousands of years older. From an NPR piece on the discovery:

Genevieve von Petzinger, a paleoanthropologist at the University of Victoria, says the discoveries in her field are happening very quickly, thanks to newer technology such as the technique used to date the hunting scene. “I think the overall theme here really is that we’ve vastly underestimated the capacity of our ancestors,” she says.

She says the oldest cave paintings in Europe and Asia have common elements. And she thinks that even older paintings will eventually be found in the place where both groups originated from.

“Personally, I think that our ancestors already knew how to do art before they left Africa,” von Petzinger says.

Von Petzinger is the scientist behind one of the most intriguing things I learned this year, that the Stone Age symbols found in caves all over the world may be part of a single prehistoric writing system.

I ran across the work of Yellena James on Instagram the other day and my inner emoji face went all heart-eyes. I love her delicate organic imagery inspired by flowers, coral, and other natural forms.

James has a lot of irons in the fire: she sells prints of her work on Etsy (scarves too!), works with a number of brands on design projects, published a book on learning how to draw using nature as a guide, regularly exhibits her art in galleries & shows, and does painting tutorials for the likes of Adobe.

For her series called Berlin, artist Diane Meyer embroiders the Berlin Wall back into modern-day scenes of the once-divided German city. Meyer hand-sews the thread right onto the photographs.

In many images, the embroidered sections represent the exact scale and location of the former Wall offering a pixelated view of what lies behind. In this way, the embroidery appears as a translucent trace in the landscape of something that no longer exists but is a weight on history and memory.

(via colossal)

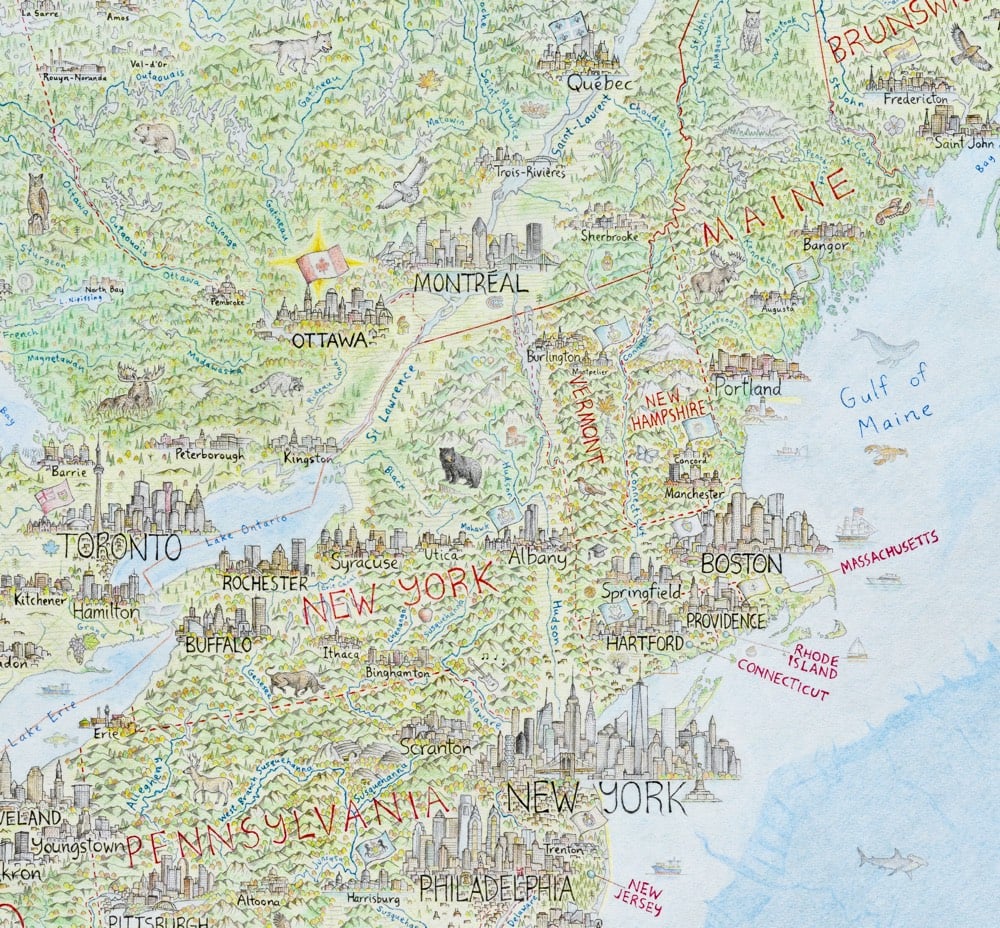

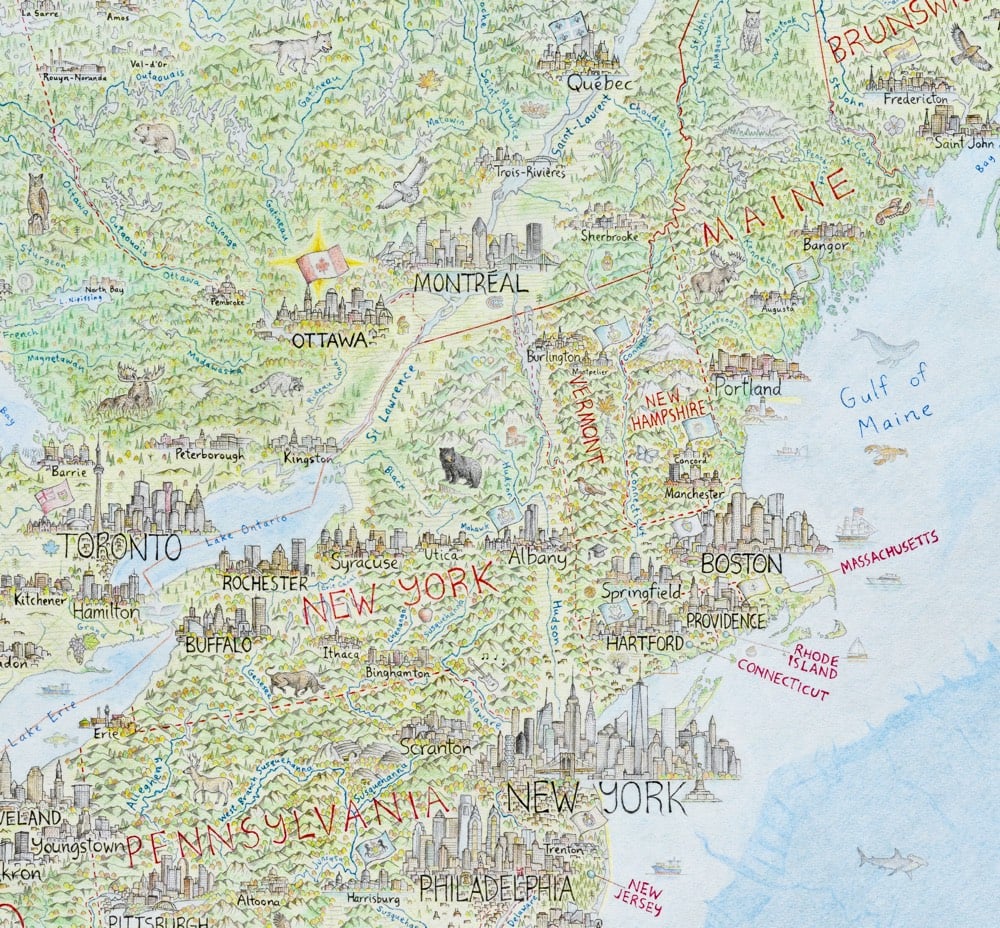

Anton Thomas has been working for the last five years on a huge hand-drawn map of North America.

North America: Portrait of a Continent is drawn completely by hand with colour pencil and pen. It is a 5 x 4 feet (150 x 120 cm) perspective projection of the entire region, spanning from Alaska to Panama; Greenland to the Caribbean. There are tens of thousands of features, including 600 individual cities and towns.

Looks fantastic. He finished it in February and is getting ready to open pre-orders for prints sometime this month.

Update: Prints of the map are available on Thomas’ store. He also made a video tour of the Mississippi River, in which he shares what all the little details on the map signify along the river’s meandering course.

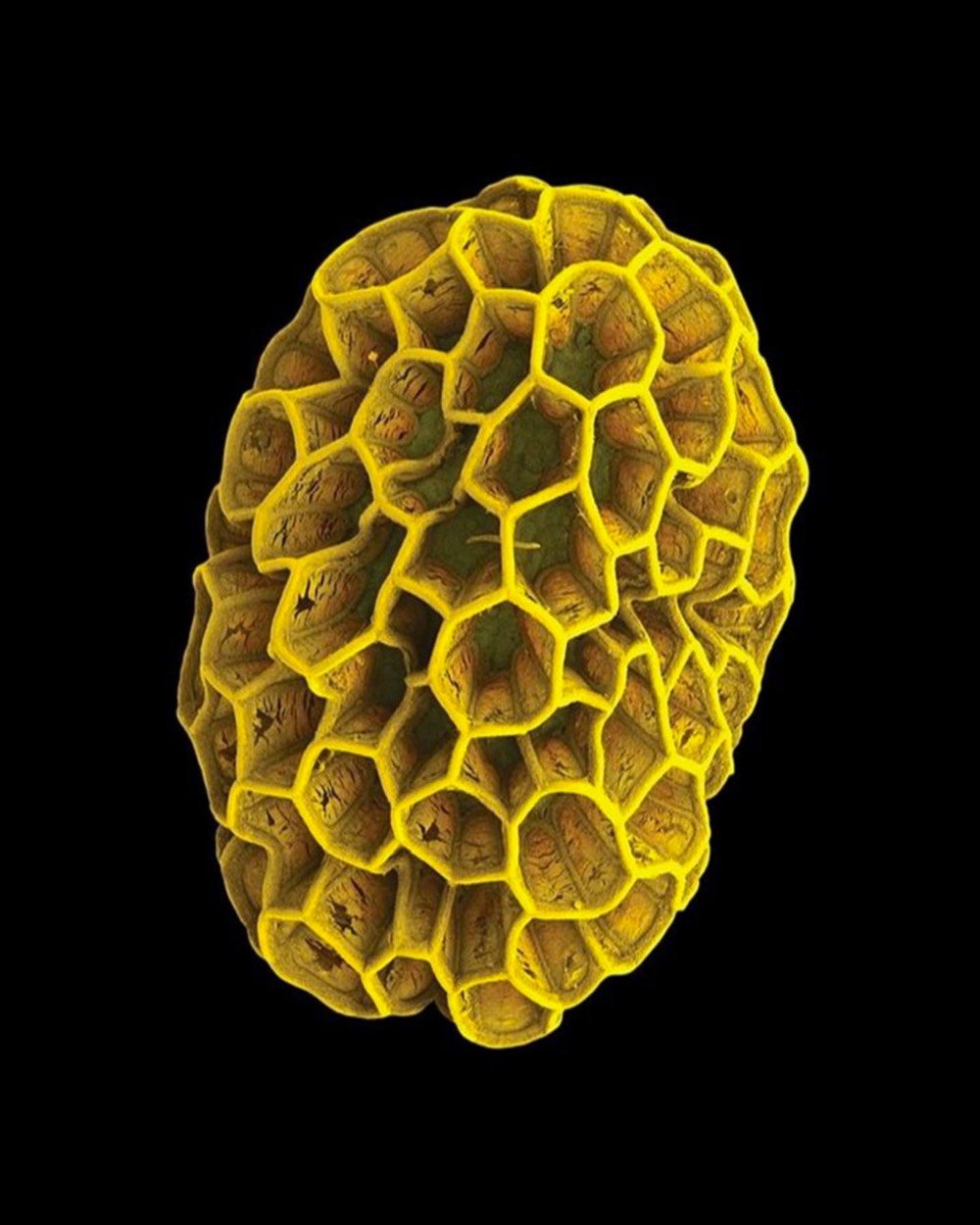

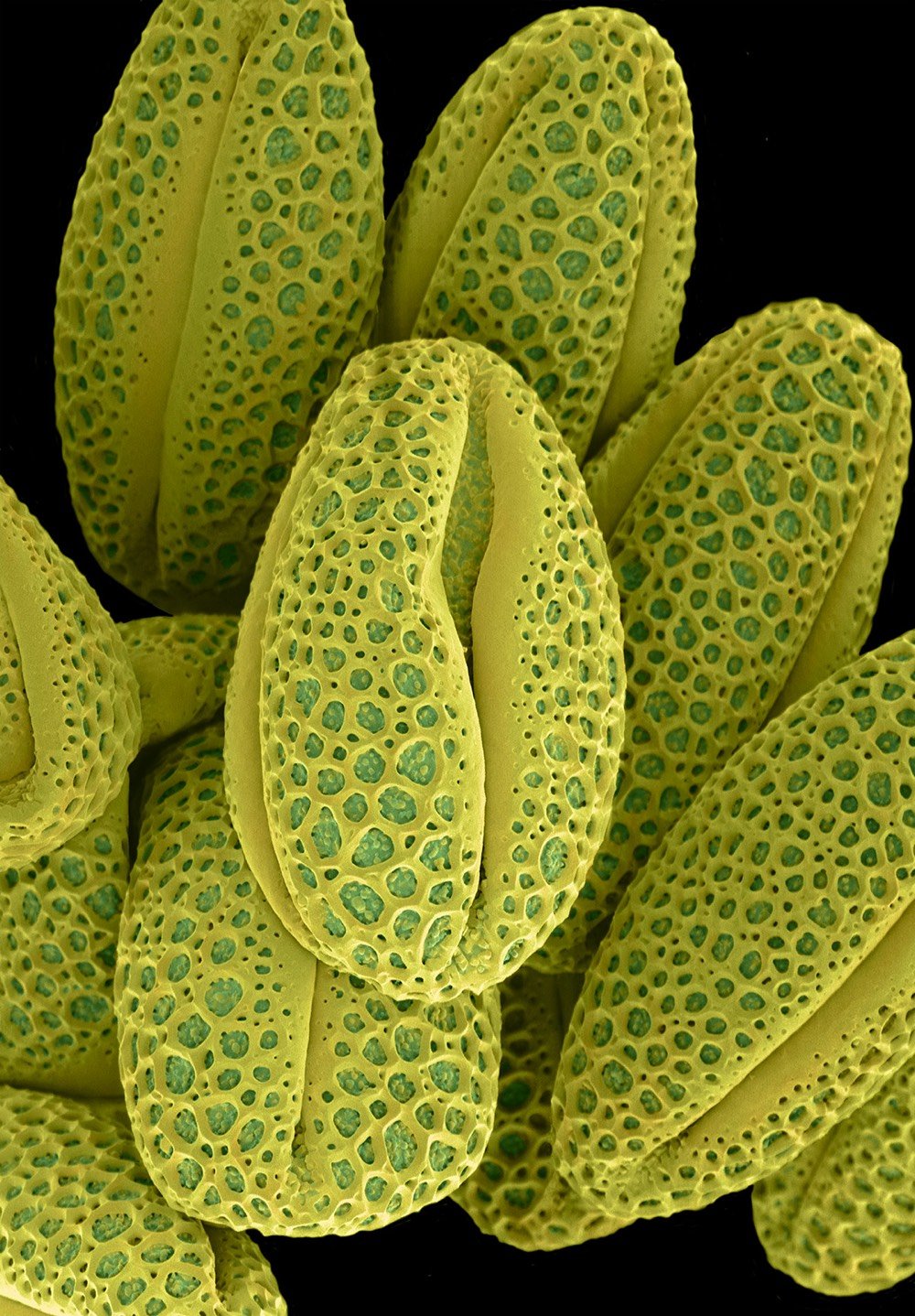

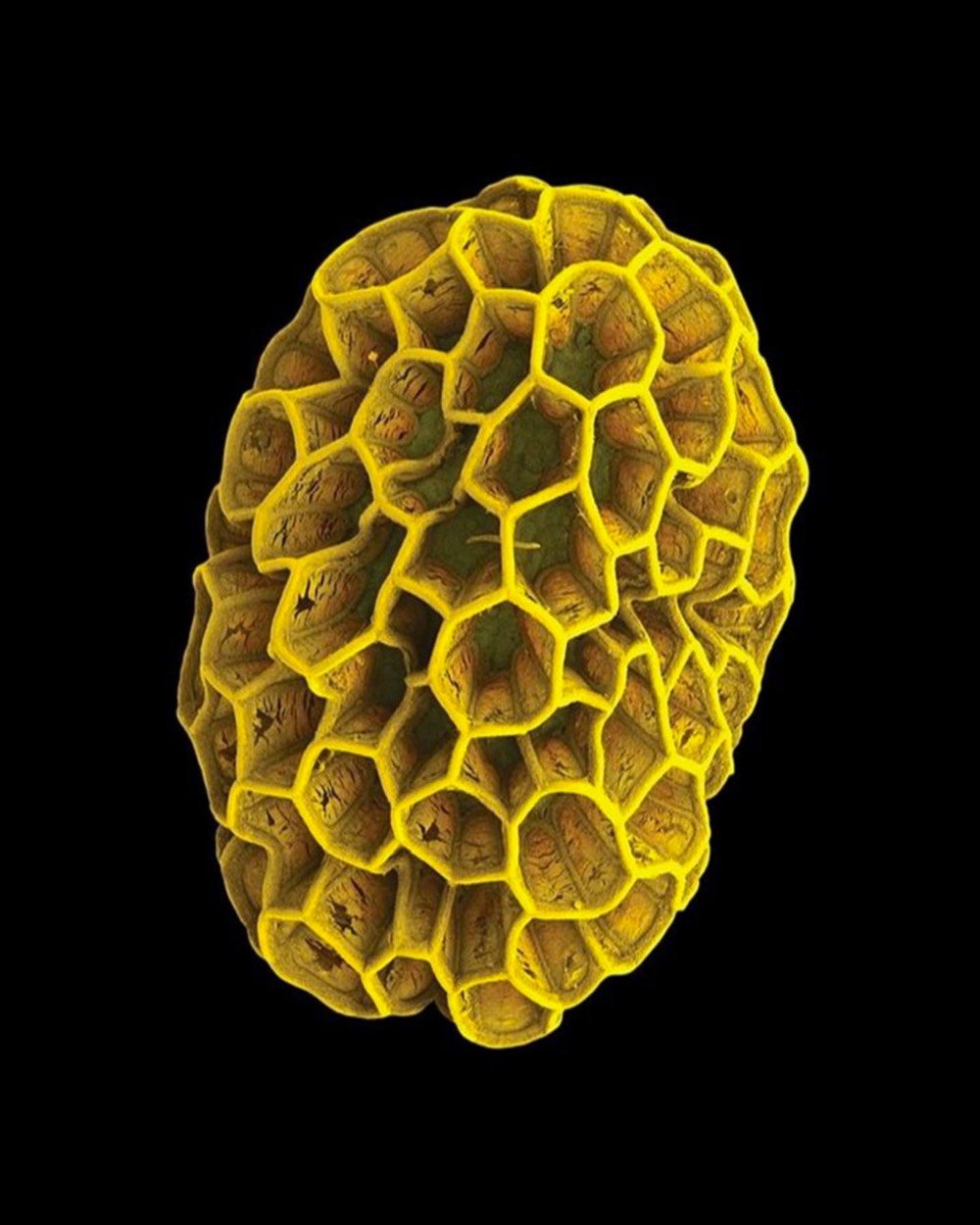

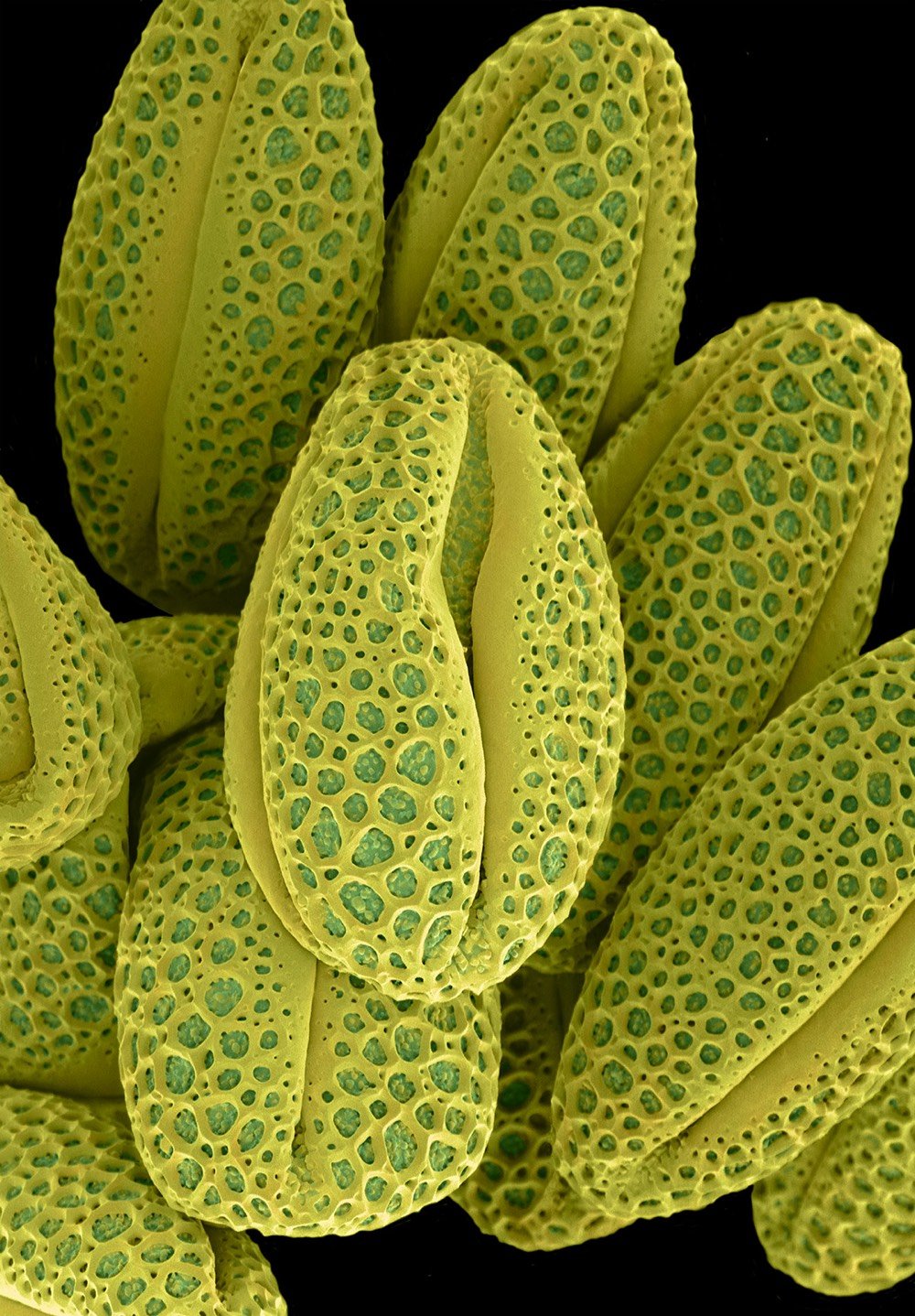

Artist Rob Kesseler is a master of the microphotography of plants and their intricately small parts (like pollen, cells, and seeds). At Colossal, Kessler says a childhood gift of a microscope set him on his way.

“What the microscope gave me was an unprecedented view of nature, a second vision,” he writes, “and awareness that there existed another world of forms, colours and patterns beyond what I could normally see.” The artist says his use of color is inspired by the time he spends researching and observing, and that just like nature, he employs it to attract attention.

Check out much more of Kesseler’s work on his website. (via colossal)

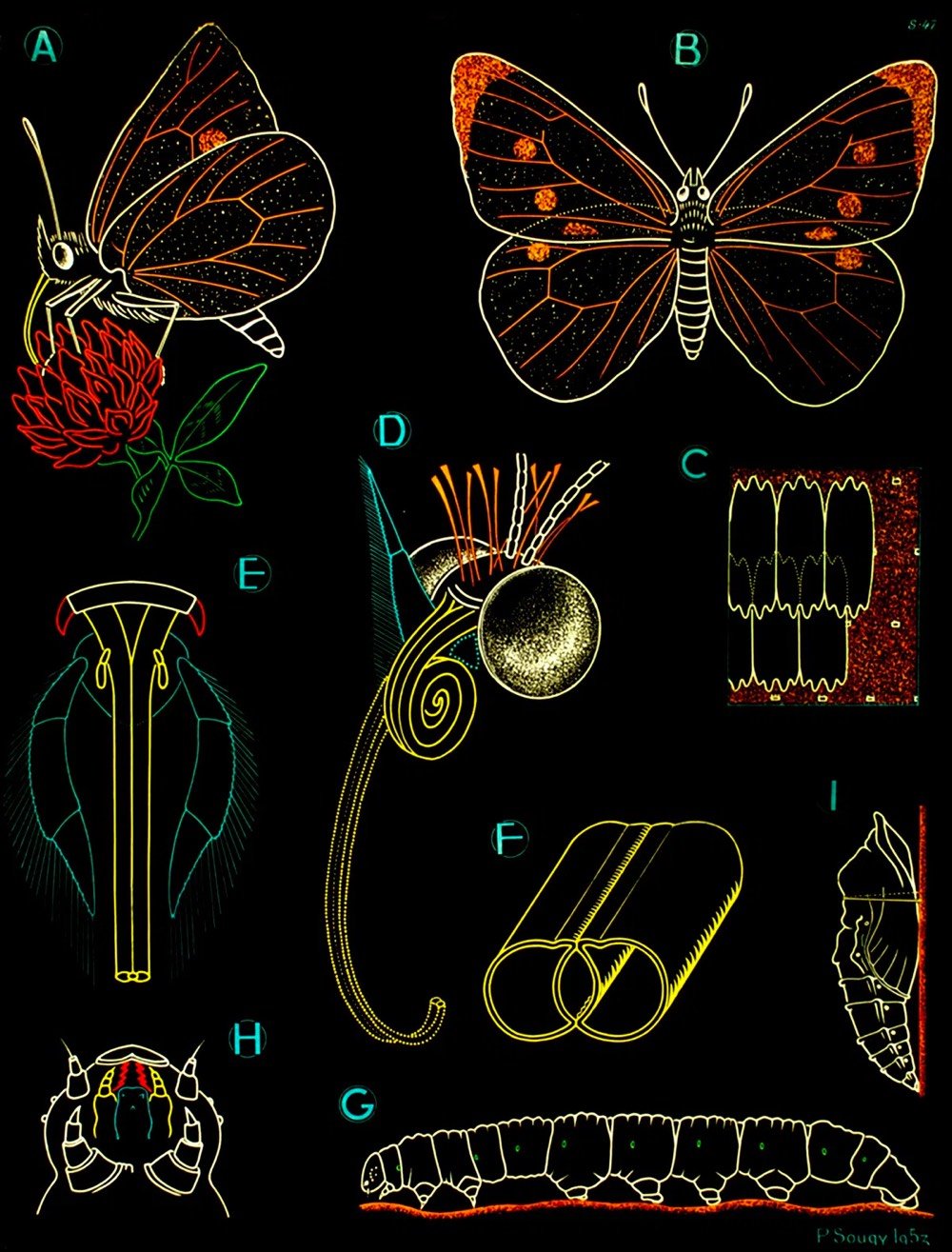

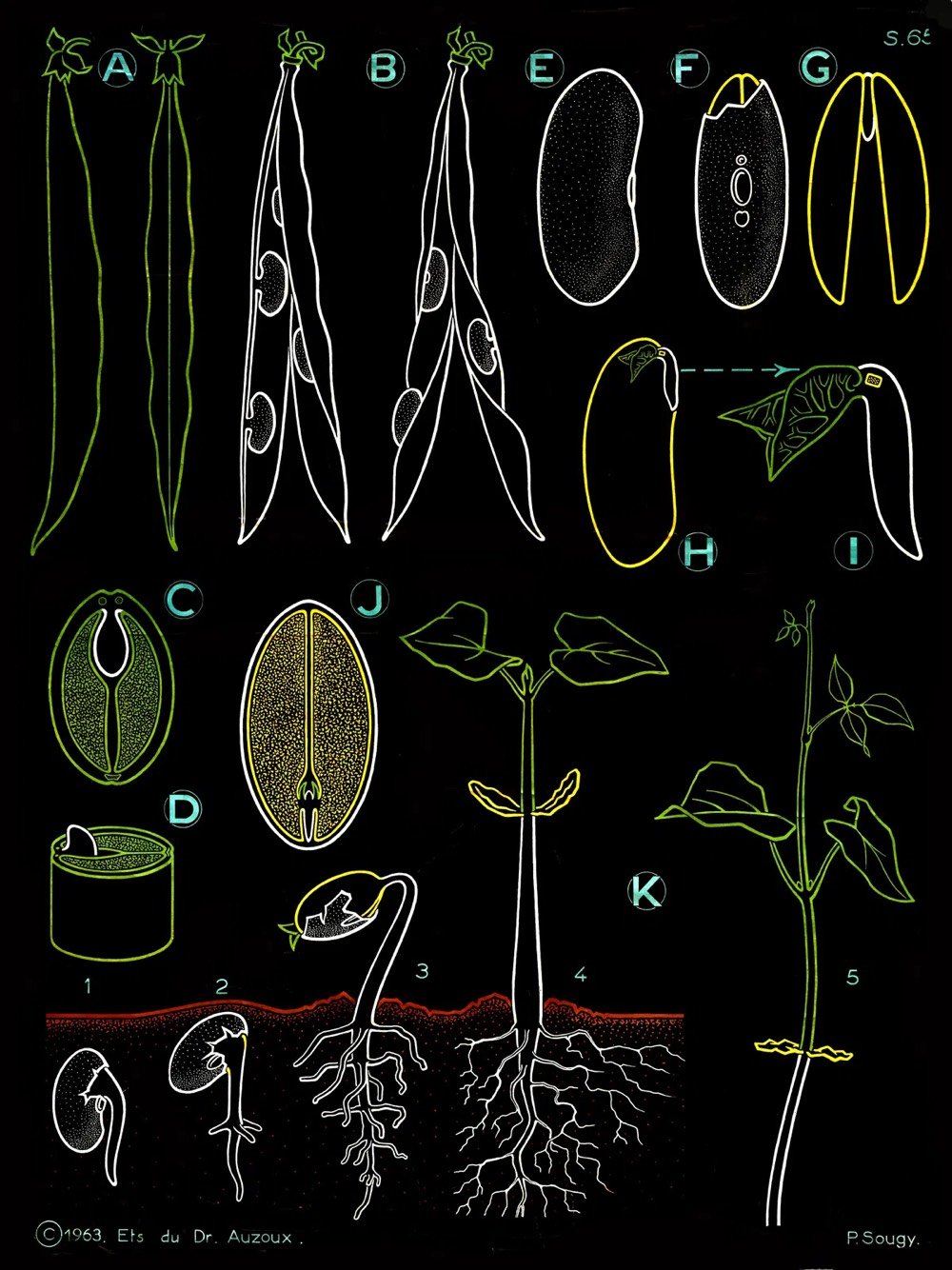

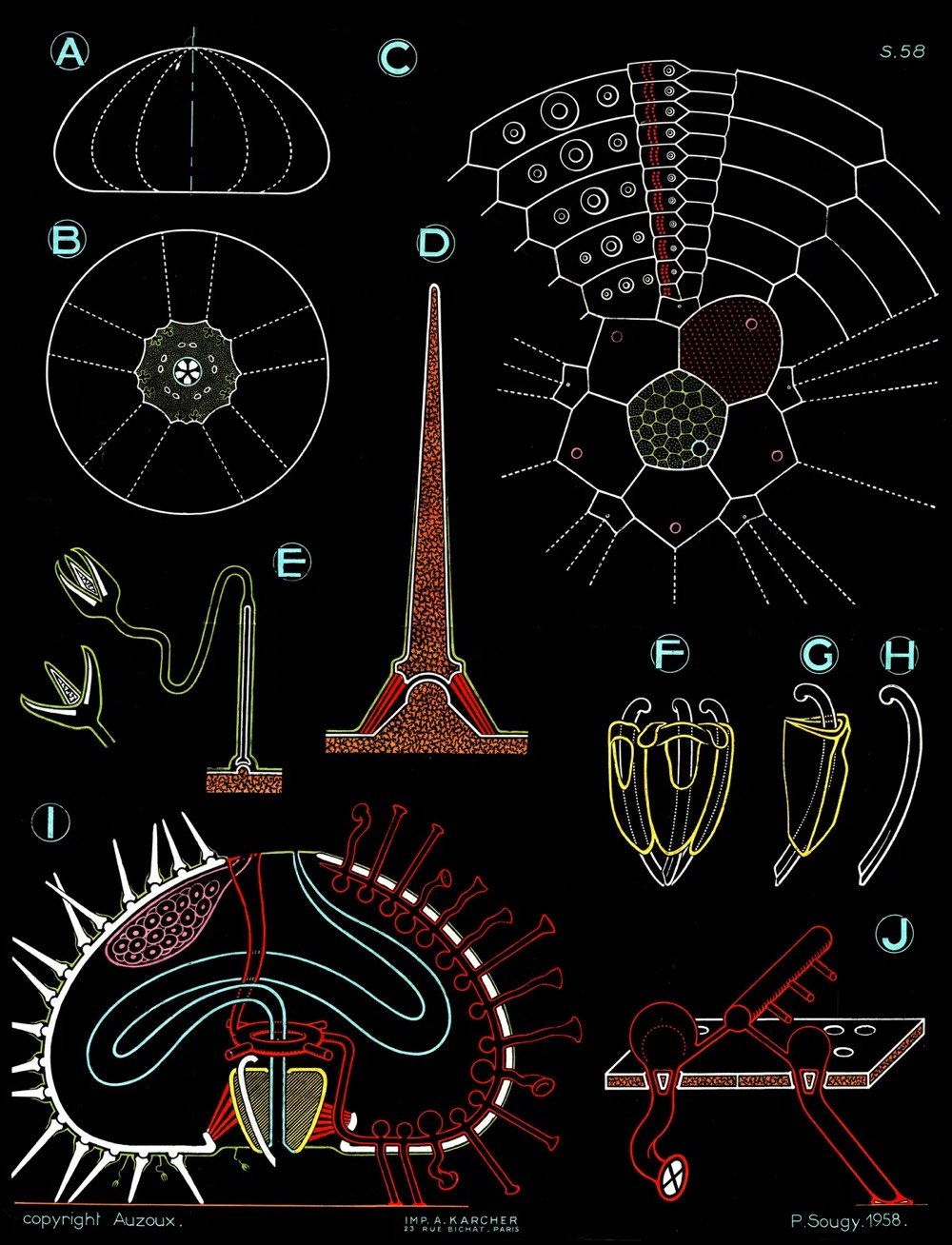

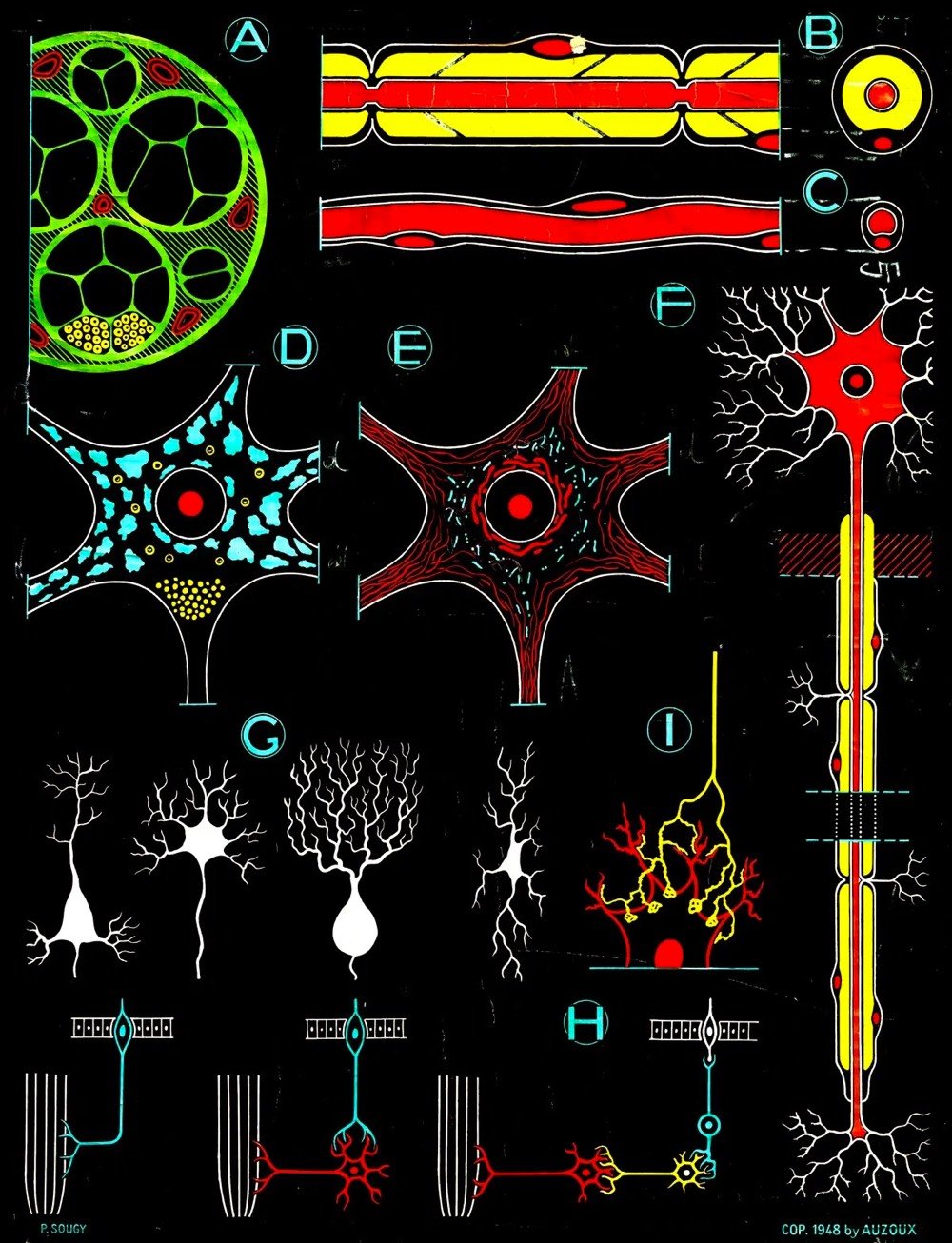

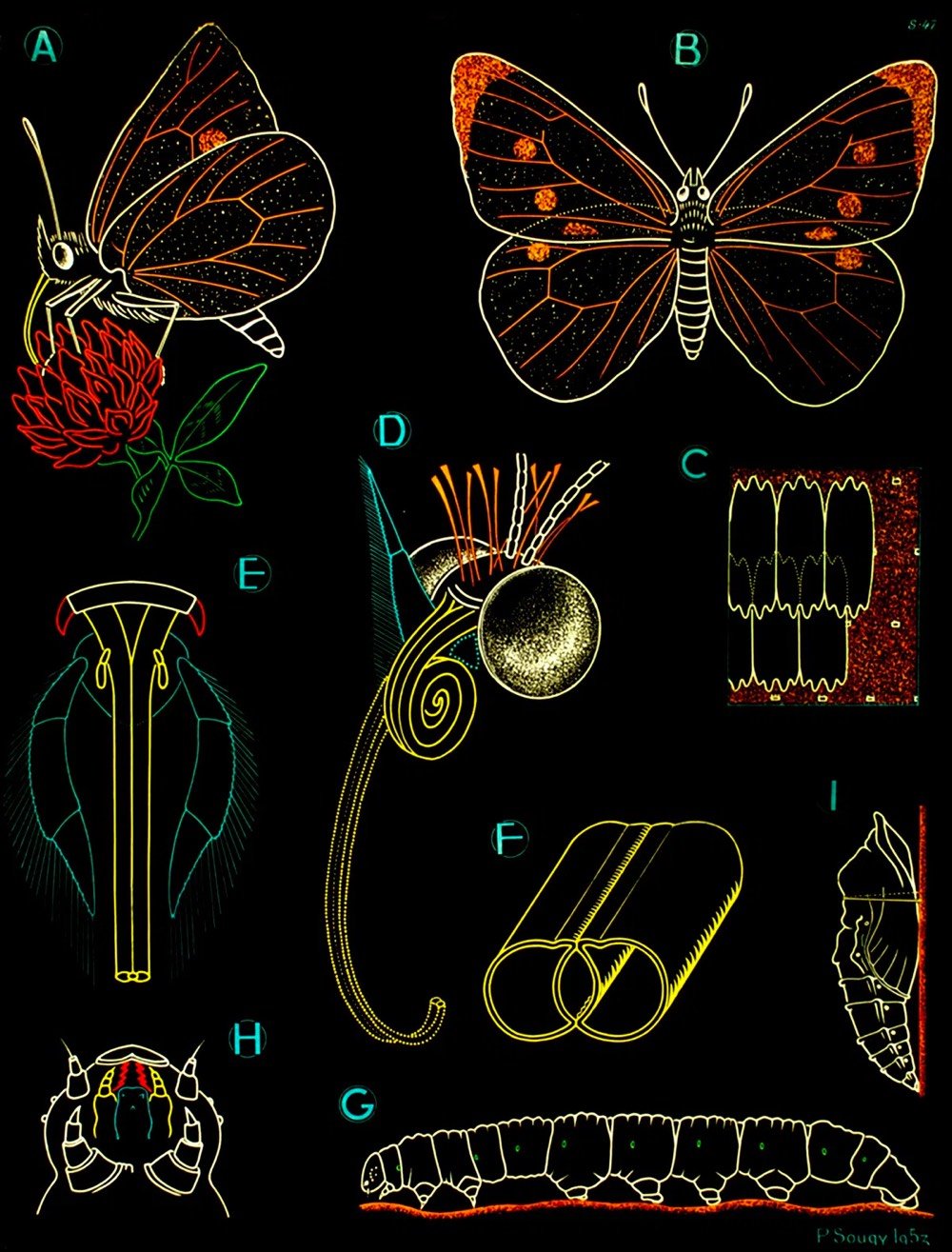

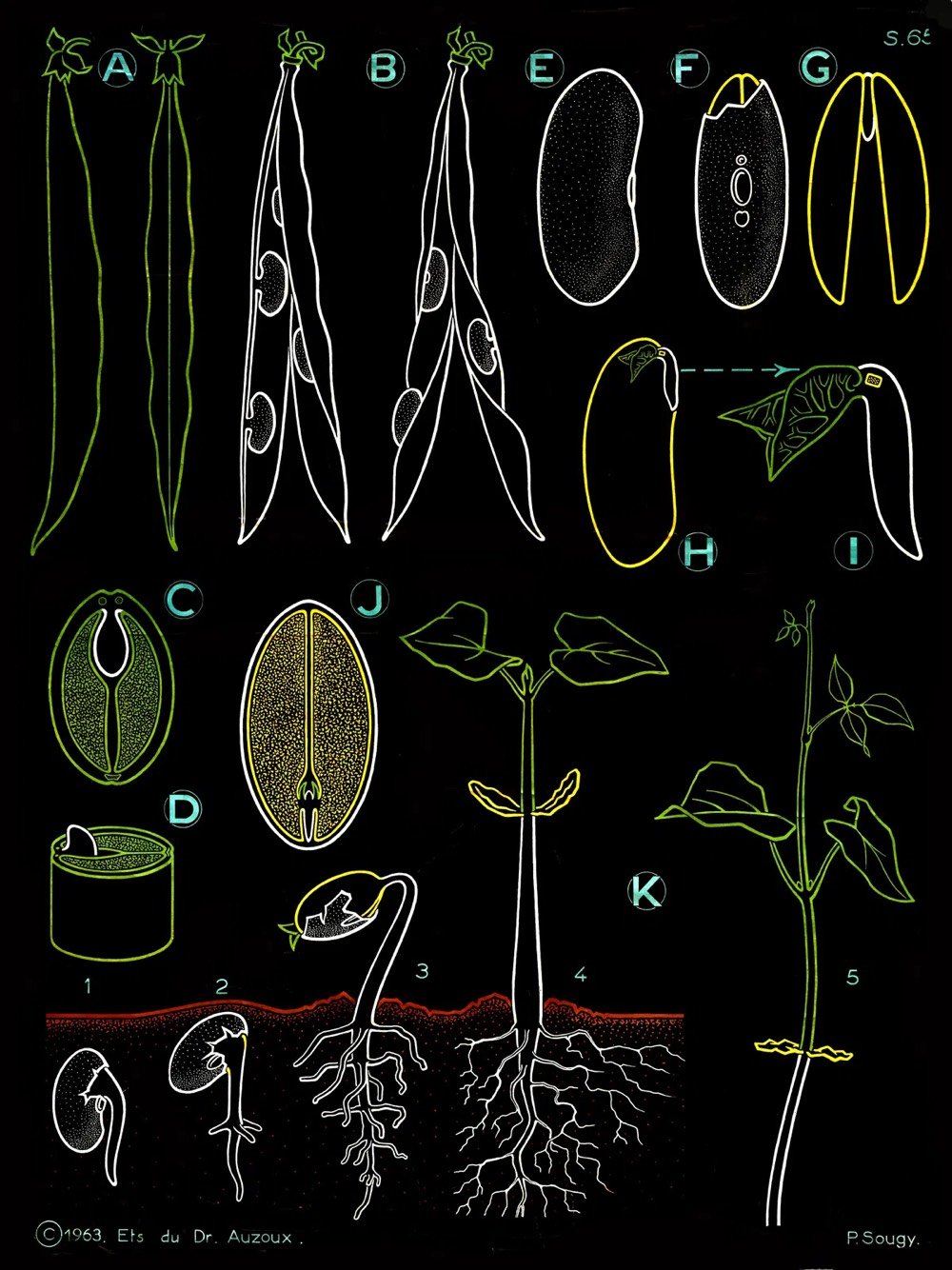

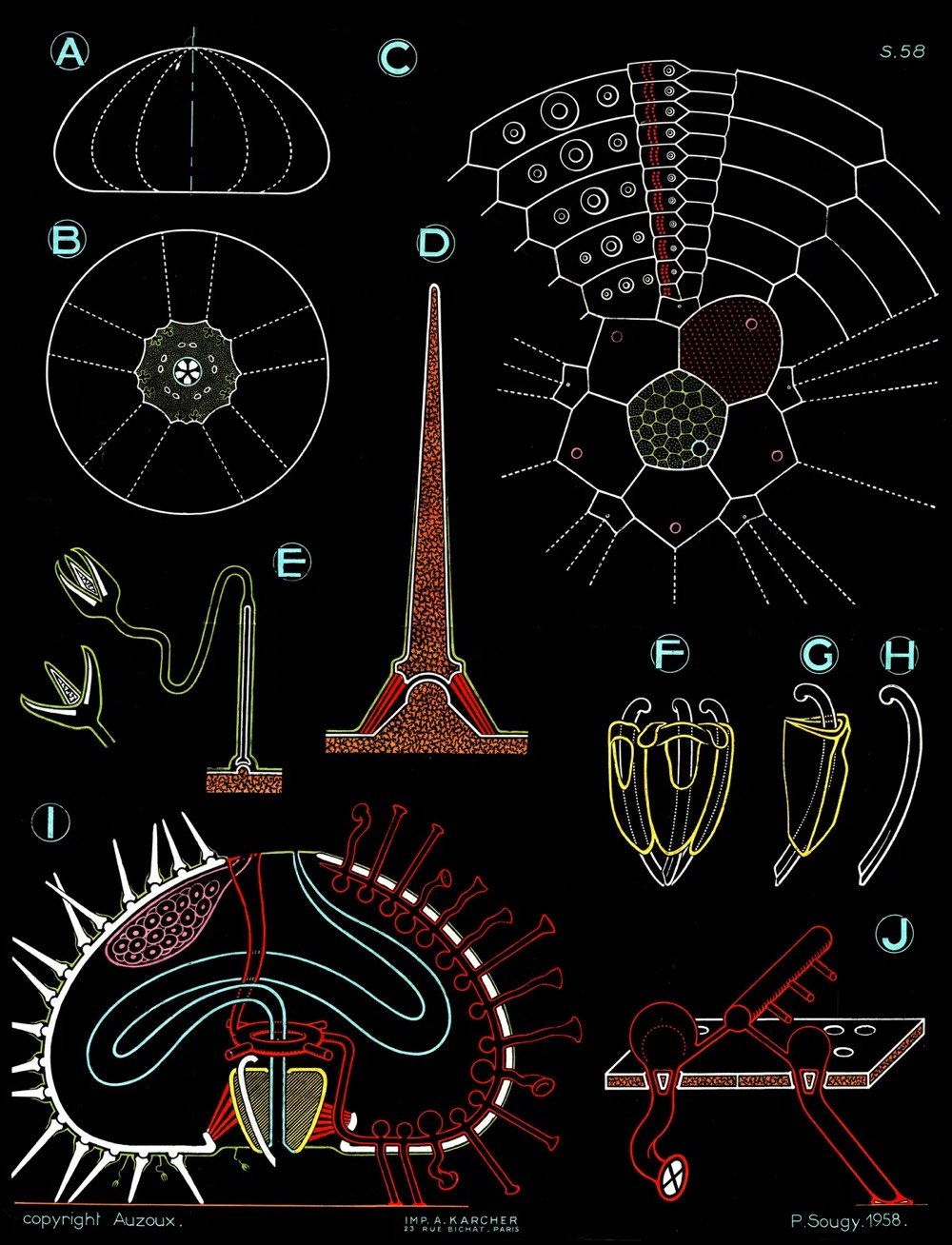

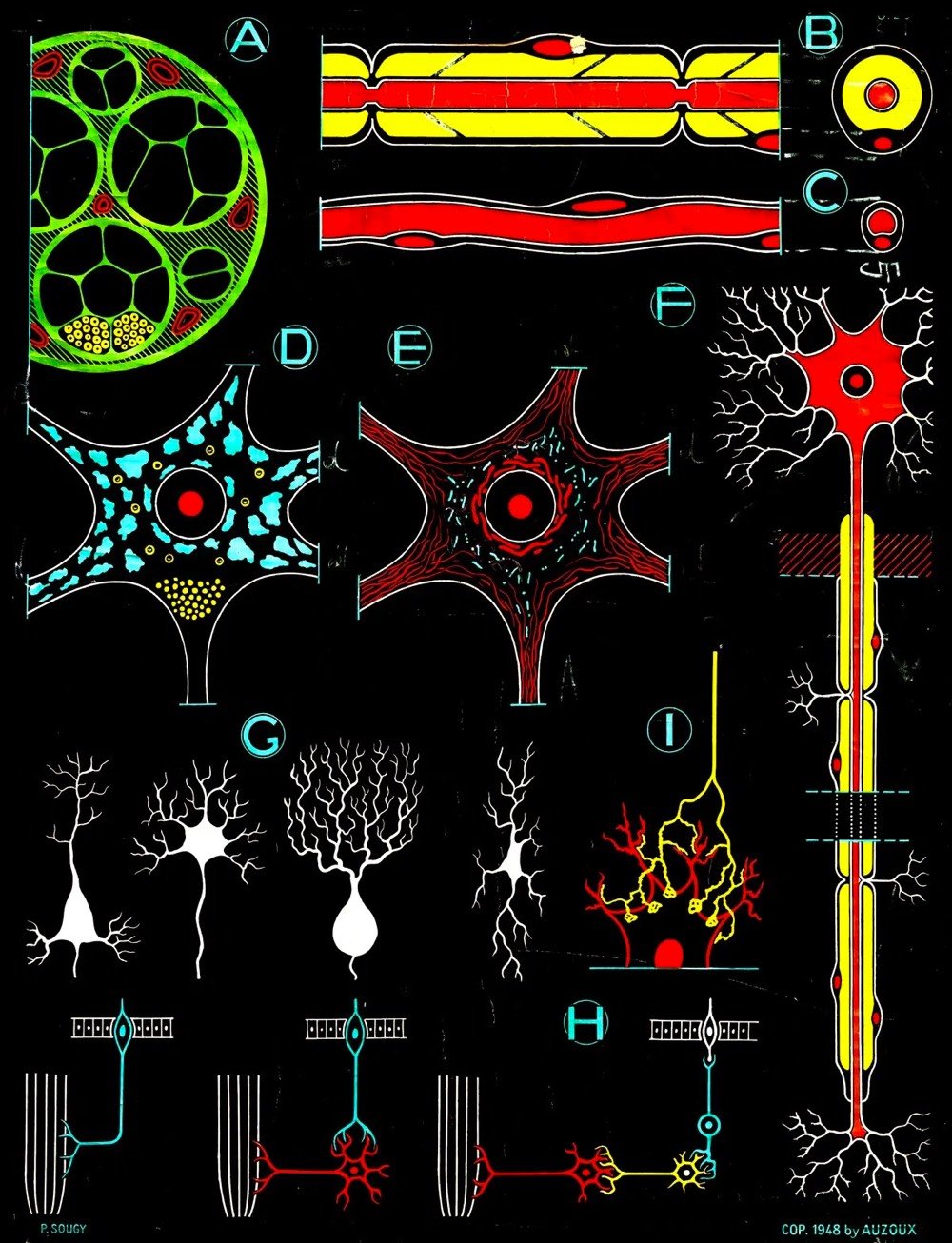

A flea market find by a friend spurred Maria Popova to rediscover and restore Paul Sougy’s mid-century educational illustrations of plants, animals, and the human body.

In the 1940s, Paul Sougy — a curator of natural history at the science museum of the French city of Orléans, and a gifted artist — was commissioned by the estate of the pioneering 18th-century French naturalist and anatomist Louis Thomas Jérôme Auzoux to create a series of illustrations based on Auzoux’s work, to be used in textbooks, workbooks, transparencies, and large-scale educational charts for classroom walls.

Lovely work. The restored illustrations are available as prints — just click on any of the images in the post or visit Popova’s Society6 shop. A portion of the proceeds go to benefit The Nature Conservancy.

The spectacular bust of Nefertiti, some 3300 years old, is currently housed at the Neues Museum in Berlin. A few years ago, high-resolution scans of the sculpture were released without permission of the museum. Now, after three years of pressure on the museum related to their claim on the bust, an official “full-color, 6.4 million-triangle 3D scan of the Bust of Nefertiti” has been released under a Creative Commons license. Cosmo Wenman has the story of how he eventually got the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation to release the scans.

For more than a decade, museums around the world have been making high-quality 3D scans of important sculptures and ancient artifacts. Some institutions, such as the Smithsonian and the National Gallery of Denmark, have forward-thinking programs that freely share their 3D scans with the public, allowing us to view, copy, adapt, and experiment with the underlying works in ways that have never before been possible. But many institutions keep their scans out of public view.

The Louvre, for example, has 3D-scanned the Nike of Samothrace and the Venus de Milo. The Galleria dell’Accademia in Florence 3D-scanned Michelangelo’s David. The Bargello has a scan of Donatello’s David. Numerous works by Auguste Rodin, including the Gates of Hell, have been scanned by the Musée Rodin in Paris. The Baltimore Museum of Art got in on the Rodin action when it scanned The Thinker. The Metropolitan Museum of Art has scans of works by Bernini, Michelangelo, and many others. But instead of allowing them to be studied, copied, and adapted by scholars, artists, and digitally savvy art lovers, these museums have kept these scans, and countless more, under lock and key.

In Berlin, the state-funded Egyptian Museum and Papyrus Collection has a high-quality, full-color 3D scan of the most iconic portrait sculpture ever produced, the 3,364-year-old Bust of Nefertiti. It has held this artifact since 1920, just a few years after its discovery in Amarna, Egypt; Egypt has been demanding its repatriation ever since it first went on display. The bust is one of the most copied works of ancient Egyptian art, and has become a cultural symbol of Berlin. For reasons the museum has difficulty explaining, this scan too is off-limits to the public.

Rather, it was off-limits. I was able to obtain it after a 3-year-long freedom of information effort directed at the organization that oversees the museum.

(via open culture)

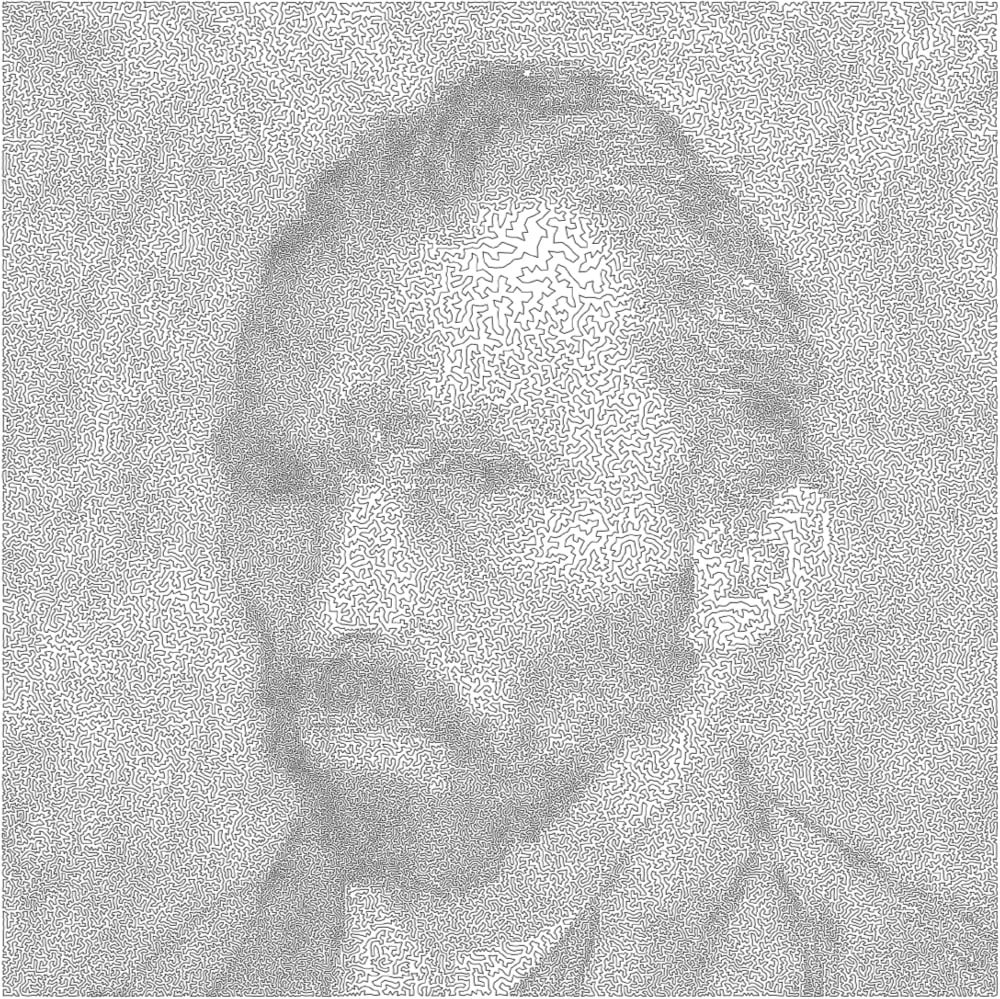

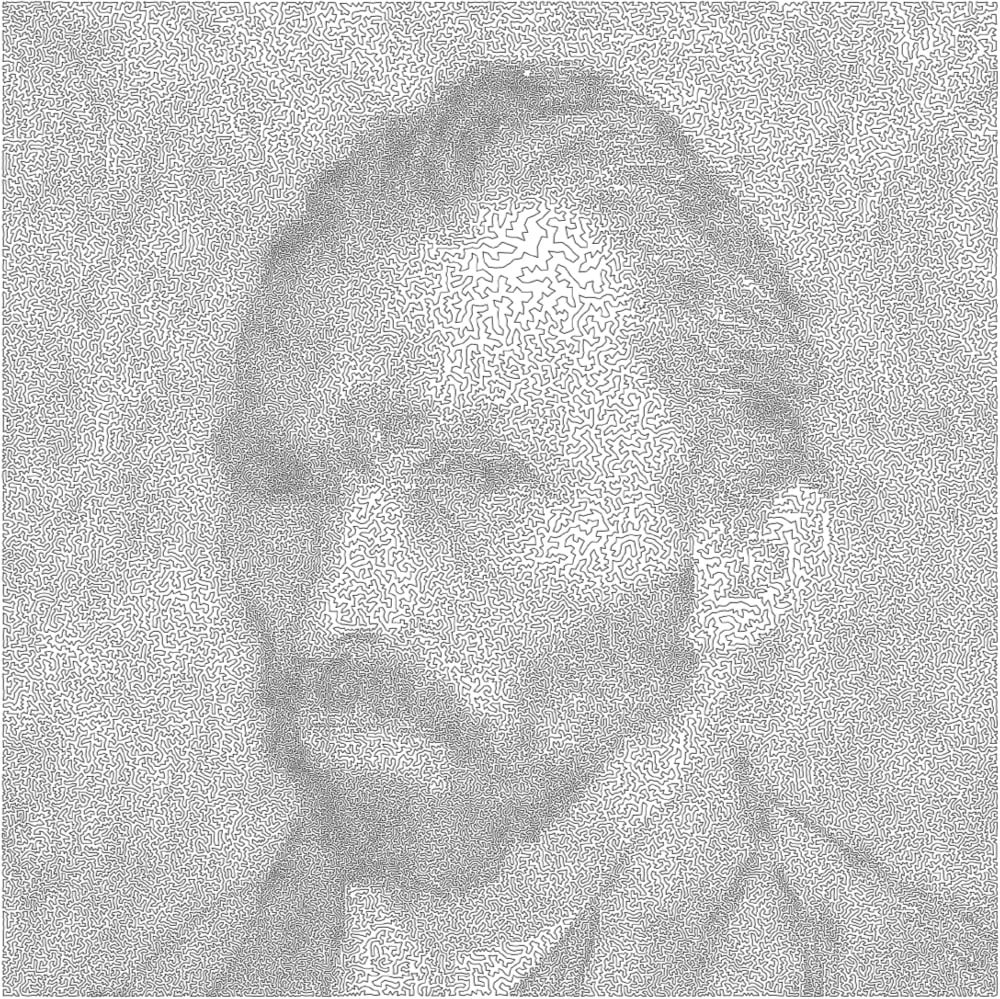

All art is bounded by one constraint or another. Mathematician Robert Bosch makes what he calls “optimization art”, which is best embodied by these images produced as solutions to the travelling salesman problem. Each image is made up of a continuous line that is the shortest possible route through a series of points without revisiting any single point, much like the optimal route of a travelling salesperson visiting cities. The rendition of a van Gogh self-portrait uses a solution for 120,000 “cities” while the single line forming the Girl with the Pearl Earring visits 200,000 cities.

I would love to see an Observable notebook where you could upload any photo to make images like these. (via @Ianmurren)

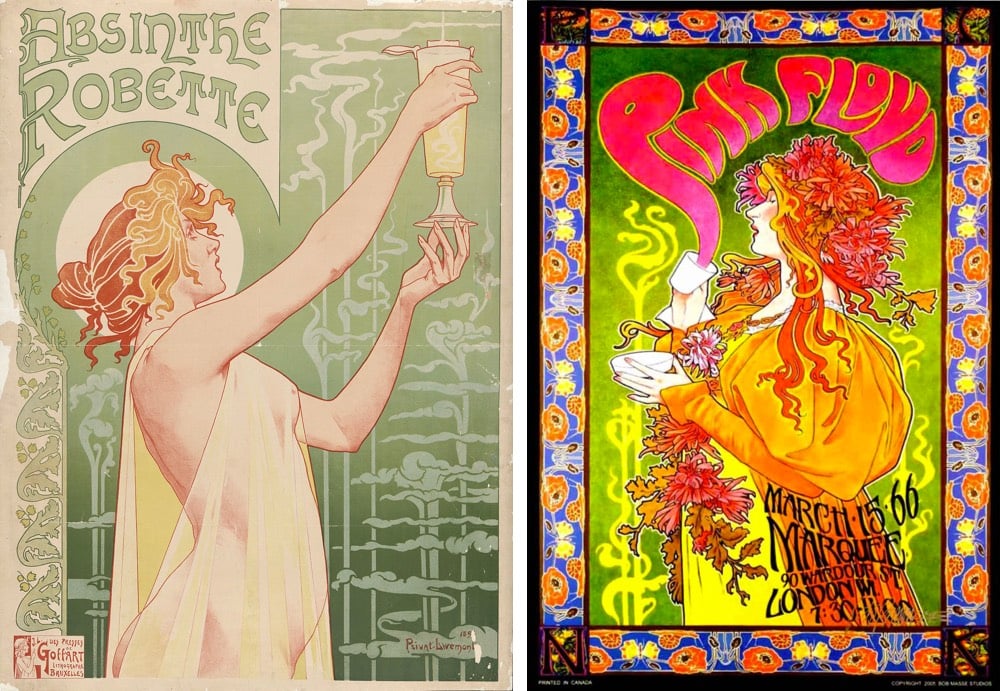

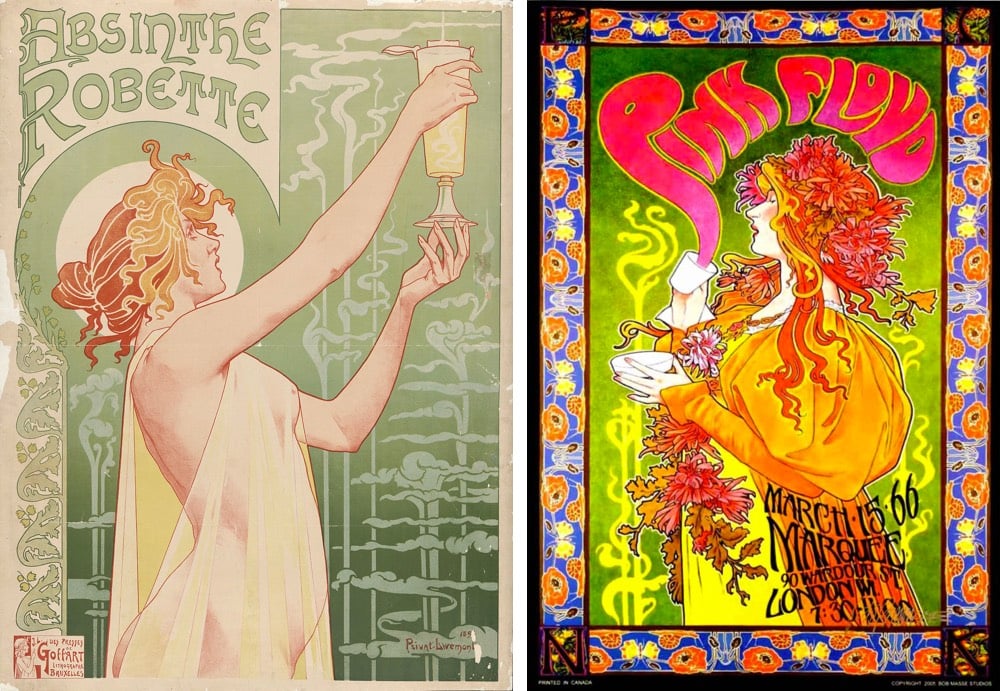

I had somehow never registered this before, but it was (ridiculously) obvious once it was pointed out to me in this video: the psychedelic design of music posters in the 60s were inspired in part by the Art Nouveau movement of the late 1800s. For instance, here’s an absinthe advertisement from the 1890s and a 1966 Pink Floyd poster.

“You can draw a straight line between Art Nouveau and psychedelic rock posters,” Martin Hohn, president of the Rock Poster Society, says. “Mucha, Jules Chéret, Aubrey Beardsley. Borrow from everything. The world is your palette. It was all meant to be populist art. It was always meant to be disposable.” He later adds: “What the artists were saying graphically was the same thing the rock bands were saying musically.”

In The Role of the Artist in the Age of Trump, playwright Lin-Manuel Miranda reflects on how truth inherent in art means that “all art is political”.

At the end of the day, our job as artists is to tell the truth as we see it. If telling the truth is an inherently political act, so be it. Times may change and politics may change, but if we do our best to tell the truth as specifically as possible, time will reveal those truths and reverberate beyond the era in which we created them. We keep revisiting Shakespeare’s Macbeth because ruthless political ambition does not belong to any particular era. We keep listening to Public Enemy because systemic racism continues to rain tragedy on communities of color. We read Orwell’s 1984 and shiver at its diagnosis of doublethink, which we see coming out of the White House at this moment.

In a 1969 piece, Kurt Vonnegut asserted that art is an early warning system for society:

I sometimes wondered what the use of any of the arts was. The best thing I could come up with was what I call the canary in the coal mine theory of the arts. This theory says that artists are useful to society because they are so sensitive. They are super-sensitive. They keel over like canaries in poison coal mines long before more robust types realize that there is any danger whatsoever.

While not specifically about art, here’s a bit of what I wrote in a January 2017 post, How to Productive in Terrible Times.

I’ve always had difficulty believing that the work I do here is in some way important to the world and since the election, that feeling has blossomed into a profound guilt-ridden anxiety monster. I mean, who in the actual fuck cares about the new Blade Runner movie or how stamps are designed (or Jesus, the blurry ham) when our government is poised for a turn towards corruption and authoritarianism?

I have come up with some reasons why my work here does matter, at least to me, but I’m not sure they’re good ones. In the meantime, I’m pressing on because my family and I rely on my efforts here and because I hope that in some small way my work, as Webb writes, “is capable of enabling righteous acts”.

(via laura olin)

You may remember the Border Wall Seesaw implemented by activist architects Ronald Rael and Virginia San Fratello earlier this year; they installed seesaws through the US/Mexico border wall, enabling people from both countries to play together on them.

This short documentary called Borderlands follows Rael to three communities along the wall — San Diego & Tijuana, Brownsville & Matamoros, El Paso & Juárez (where he installed the seesaws) — where the connections between the US & Mexican sides persist and flourish despite their artificial separation.

Rael is well aware that, not too long ago, the boundary between the United States and Mexico, which is now delineated by more than seven hundred miles of fencing, was an open frontier, dotted with stone monuments. His book “Borderwall as Architecture” makes clear that the billions of dollars the U.S. government has spent on curbing migration and enhancing border security have done little to deter those intent on crossing by foot, using wooden ladders and ramps, or through tunnels. Decades of flawed policies suggest that the building of a grand wall is entirely divorced from the reality on the ground.

See also Best of Luck With the Wall, Josh Begley’s satellite image tour of the wall from the Pacific to the Gulf.

Ok, this post doesn’t have anything to do with boy detective Encyclopedia Brown…I just needed him for the title. In the NY Times, art critic Jason Farago argues that in order to improve the visitor experience at the Louvre, the Mona Lisa and her smile have got to go.

Yet the Louvre is being held hostage by the Kim Kardashian of 16th-century Italian portraiture: the handsome but only moderately interesting Lisa Gherardini, better known (after her husband) as La Gioconda, whose renown so eclipses her importance that no one can even remember how she got famous in the first place.

Some 80 percent of visitors, according to the Louvre’s research, are here for the Mona Lisa — and most of them leave unhappy. Content in the 20th century to be merely famous, she has become, in this age of mass tourism and digital narcissism, a black hole of anti-art who has turned the museum inside out.

Enough!

I visited the Louvre back in 2017 and the Mona-driven crowds were very distracting. I wrote a short review for my media diet:

The best-known works are underwhelming and the rest of this massive museum is overwhelming. The massive crowds, constant photo-taking, and selfies make it difficult to actually look at the art. Should have skipped it.

The Louvre is actually not a good place to look at art and if moving the Mona Lisa to a dedicated gallery elsewhere can help solve that problem, they should do it. (via @fimoculous)

From the NY Times, Philip Glass Is Too Busy to Care About Legacy.

“I’m pragmatic,” Mr. Glass said. “I don’t know what’s going to happen in 10 years. We don’t even get to know what’s going to happen after someone dies. We need to wait until everyone who knew them is dead, too.”

If that’s true, it won’t be until nearly 2100 when a full measure of Mr. Glass’s footprint will be possible. But some weighing can start now. The most instantly recognizable voice in contemporary music, he opened a new chapter in operatic history, pushing the bounds of duration and abstraction. At a time when the most lauded composers disdained overproduction, Mr. Glass wrote unashamedly for everyone and everything — and all stubbornly in the distinctive style he created, establishing a model for serious artists moving from the opera house to the concert hall to the film studio, garnering both Met commissions and Academy Award nominations.

But if the question is whether, a century from now, his operas will get new productions, his symphonies will circulate more frequently, or pianists will take on his études, Mr. Glass couldn’t care less.

“I won’t be around for all that,” he said. “It doesn’t matter.”

Austin Kleon expanded on this piece with some thoughts about lineage vs legacy.

I like this idea of thinking about lineage vs. legacy, because it means you can sort of reframe any worrying about immortality and how you’re going to project yourself into the future, and think more about what you’re taking from the past and what you’re adding to it that creates a more interesting and helpful present.

Newer posts

Older posts

Socials & More