This is from a few days ago, but because the United States is a couple of weeks behind Italy in addressing the COVID-19 pandemic, what was happening there then might still be in our future if we don’t take (seemingly unreasonable but actually entirely reasonable) precautions. From Yascha Mounk’s The Extraordinary Decisions Facing Italian Doctors:

The authors, who are medical doctors, then deduce a set of concrete recommendations for how to manage these impossible choices, including this: “It may become necessary to establish an age limit for access to intensive care.”

Those who are too old to have a high likelihood of recovery, or who have too low a number of “life-years” left even if they should survive, would be left to die. This sounds cruel, but the alternative, the document argues, is no better. “In case of a total saturation of resources, maintaining the criterion of ‘first come, first served’ would amount to a decision to exclude late-arriving patients from access to intensive care.”

In addition to age, doctors and nurses are also advised to take a patient’s overall state of health into account: “The presence of comorbidities needs to be carefully evaluated.” This is in part because early studies of the virus seem to suggest that patients with serious preexisting health conditions are significantly more likely to die. But it is also because patients in a worse state of overall health could require a greater share of scarce resources to survive: “What might be a relatively short treatment course in healthier people could be longer and more resource-consuming in the case of older or more fragile patients.”

Mounk continues:

My academic training is in political and moral philosophy. I have spent countless hours in fancy seminar rooms discussing abstract moral dilemmas like the so-called trolley problem. If a train is barreling toward five innocent people who are tied to the tracks, and I could divert it by pulling the lever, but at the cost of killing an innocent bystander, should I do it?

Part of the point of all those discussions was, supposedly, to help professionals make difficult moral choices in real-world circumstances. If you are an overworked nurse battling a novel disease under the most desperate circumstances, and you simply cannot treat everyone, however hard you try, whose life should you save?

Despite those years of theory, I must admit that I have no moral judgment to make about the extraordinary document published by those brave Italian doctors. I have not the first clue whether they are recommending the right or the wrong thing.

I have been rewatching The Good Place with my kids (they love it), and all of the moral philosophy stuff underpinning the show has taken on a greater meaning over the last week or two.

Yascha Mounk writing for The Atlantic:

These three facts imply a simple conclusion. The coronavirus could spread with frightening rapidity, overburdening our health-care system and claiming lives, until we adopt serious forms of social distancing.

This suggests that anyone in a position of power or authority, instead of downplaying the dangers of the coronavirus, should ask people to stay away from public places, cancel big gatherings, and restrict most forms of nonessential travel.

Given that most forms of social distancing will be useless if sick people cannot get treated-or afford to stay away from work when they are sick-the federal government should also take some additional steps to improve public health. It should take on the costs of medical treatment for the coronavirus, grant paid sick leave to stricken workers, promise not to deport undocumented immigrants who seek medical help, and invest in a rapid expansion of ICU facilities.

This is very close to my own personal thinking right now, particularly after watching this excellent video about exponential growth and epidemics.

In an effort to discover what effect populist leaders have on democratic institutions, a pair of researchers, Harvard’s Yascha Mounk and Jordan Kyle of the Tony Blair Institute for Global Change, compiled a list of 46 populist leaders & parties that have been in power in democracies from 1990 until now. Then they looked at how those leaders affected those governmental systems in those countries. Their conclusions were not encouraging: “Populists are highly skilled at staying in power and pose an acute danger to democratic institutions.”

Populists aren’t just more likely to win reelection once or twice; they are also much more likely to remain in power for well over a decade. Six years after they are first elected, populist leaders are twice as likely as non-populist leaders to still be in power; twelve years after they are first elected, they are more than five times as likely.

Arguably, these findings are not, in themselves, all that concerning: The longer survival rate for populists may simply reflect their efficiency or popularity. But among populist leaders who entered office between 1990 and 2015, only a small minority left office as a result of the normal democratic process.

In fact, only 17 percent of populists stepped down after they lost free and fair elections. Another 17 percent vacated high office after they reached their term limits. But 23 percent left office under more dramatic circumstances — they were impeached or forced to resign. Another 30 percent of all populist leaders in our database remain in power to this day. This is partially a function of the recent rise of populism: Thirty-six percent of those populist rulers who still remain in power were elected over the past five years. But even more of them have been in office long enough to raise serious concerns: About half have led their country for at least nine years.

The most important issue, however, is neither how long populists stay in office nor even how they ultimately leave, but what they do with their power-and, in particular, whether their tenure causes what political scientists call “democratic backsliding,” a significant deterioration in the extent to which the citizens enjoy basic rights.

Here, too, our findings were sobering, to say the least: In many countries, populists rewrote the rules of the game to permanently tilt the electoral playing field in their favor. Indeed, an astounding 50 percent of populists either rewrote or amended their country’s constitution when they gained power, frequently with the aim of eliminating presidential term limits and reducing checks and balances on executive power.

Their full paper is available here, which shows that left-wing populism is almost as bad as right-wing populism:

Between 1990 and 2014, 13 right-wing populist governments were elected; of these, five have significantly curtailed civil liberties and political rights, as measured by Freedom House. Over the same period, 15 left-wing populist governments were elected; of these, the same number reduced such freedoms. (Over the same period, there were also 17 populist governments that cannot easily be classified as either right- or left-wing; again, five of these governments diminished civil liberties and political rights.) Although this indicates a slightly higher rate of backsliding among right-wing populists than left-wing ones (38 per cent vs. 33 per cent), these data clearly contradict the belief that left-wing populism does not pose a threat to democracy.

Political scientists Yascha Mounk and Roberto Stefan Foa have been doing research on the stability of contemporary liberal democracies, looking in particular at the assumption a country becomes a democracy, it will stay that way. Their conclusion? We may be in trouble: “liberal democracies around the world may be at serious risk of decline”.

But since 2005, Freedom House’s index has shown a decline in global freedom each year. Is that a statistical anomaly, a result of a few random events in a relatively short period of time? Or does it indicate a meaningful pattern?

Mr. Mounk and Mr. Foa developed a three-factor formula to answer that question. Mr. Mounk thinks of it as an early-warning system, and it works something like a medical test: a way to detect that a democracy is ill before it develops full-blown symptoms.

The first factor was public support: How important do citizens think it is for their country to remain democratic? The second was public openness to nondemocratic forms of government, such as military rule. And the third factor was whether “antisystem parties and movements” — political parties and other major players whose core message is that the current system is illegitimate — were gaining support.

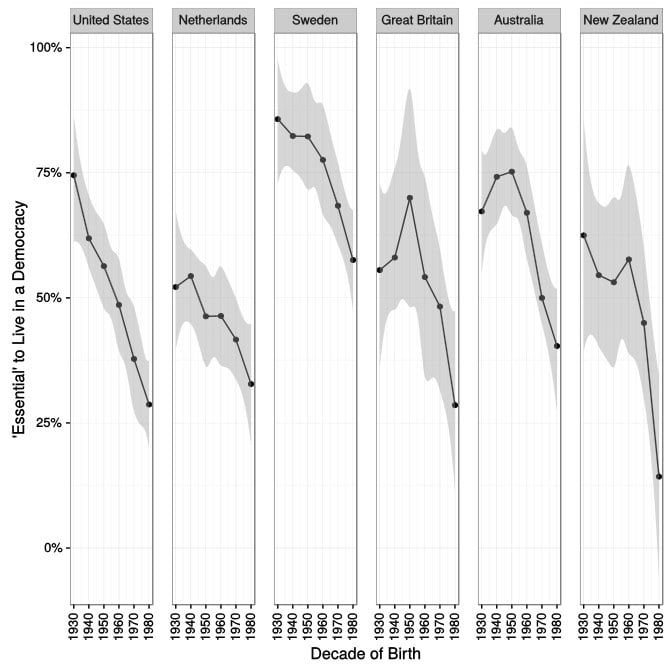

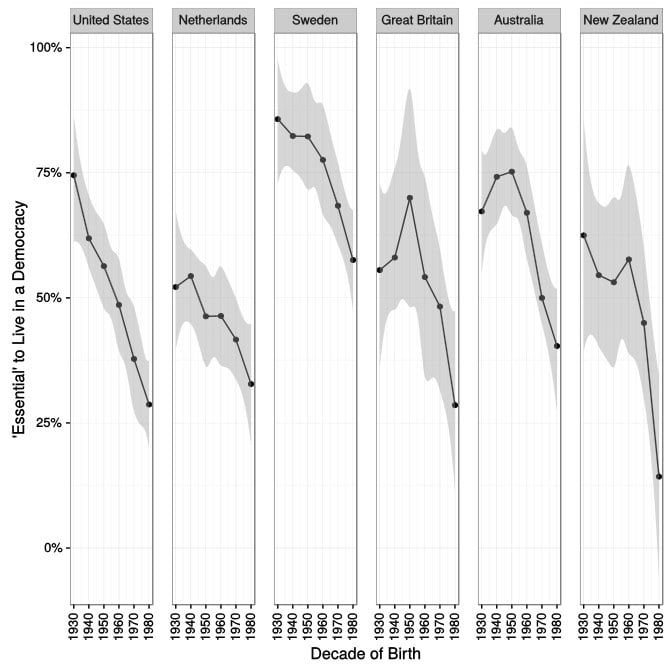

Regarding that first factor, public support for democracy, their research indicates a worrying trend: younger people around the world think it’s less “essential” to live in a democracy.

Younger people would also be more in favor of military rule:

Support for autocratic alternatives is rising, too. Drawing on data from the European and World Values Surveys, the researchers found that the share of Americans who say that army rule would be a “good” or “very good” thing had risen to 1 in 6 in 2014, compared with 1 in 16 in 1995.

That trend is particularly strong among young people. For instance, in a previously published paper, the researchers calculated that 43 percent of older Americans believed it was illegitimate for the military to take over if the government were incompetent or failing to do its job, but only 19 percent of millennials agreed. The same generational divide showed up in Europe, where 53 percent of older people thought a military takeover would be illegitimate, while only 36 percent of millennials agreed.

What’s interesting is that Trump, who Mounk believes is a threat to liberal democracy in the US, drew his support from older Americans, which would seem to be a contradiction. It is also unclear if young people have always felt this way (i.e. do people appreciate democracy more as they get older?) or if this is a newly growing sentiment (i.e. people are now less appreciative of democracy, young people particularly so).

Something I think about often is cultural memory and how it shifts, seen most notably on kottke.org in my mild obsession with The Great Span. Back in July, writer John Scalzi tweeted:

Sometimes feels like a strong correlation between WWII passing from living memory, and autocracy seemingly getting more popular.

Scalzi is on to something here, I think. Those who fought in or lived through World War II are either dead or dying. Their children, the Baby Boomers, had a very different experience in hunky dory Leave It to Beaver postwar America.1 Anyone under 50 probably doesn’t remember anything significant about the Vietnam War and anyone under 35 didn’t really experience the Cold War.2 Couple that with an increasingly poor educational experience in many areas of the country and it seems as though Americans have forgotten how bad it was (Stalin, Hitler, the Holocaust, Vietnam, the Cold War) and take for granted the rights and protections that liberal democracy, despite its faults, offers its citizens. Shame on us if we throw all of that hard-fought progress away in exchange for — how did Franklin put it? — “a little temporary safety”.

Update: The graph above showing public support for democracy is misleading and overly dramatic. Looking at the average scores is more instructive for people’s feelings on democracy:

So where does this graph go wrong? It plots the percentage of people who answer 10, and it treats everyone else the same. The graph treats the people who place themselves at 1 as having the same commitment to democracy as those who answer 9. In reality, almost no one (less than 1 percent) said that democracy is “not at all important.”

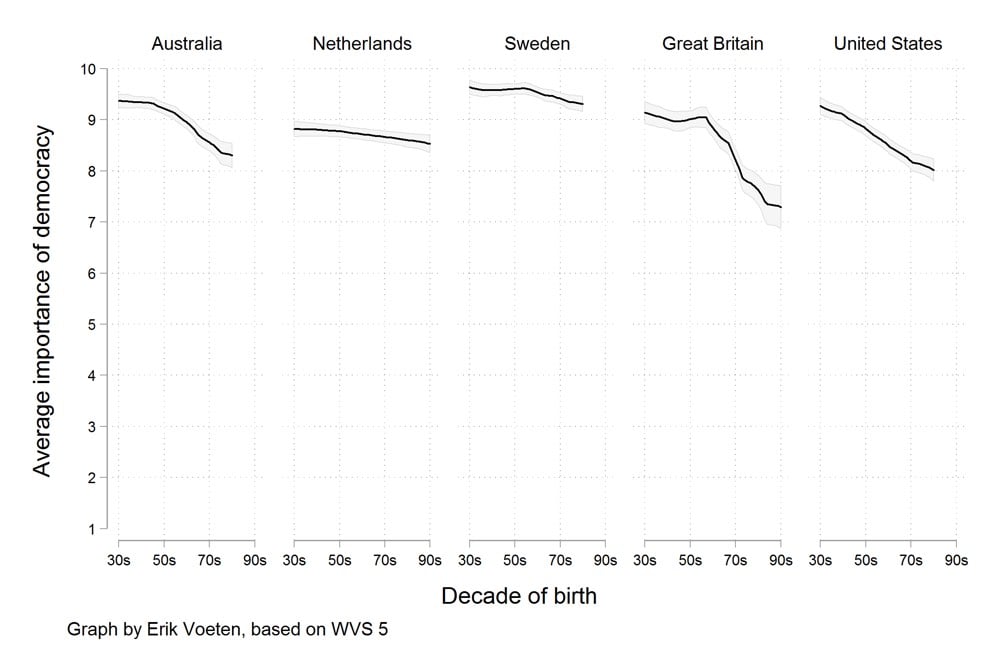

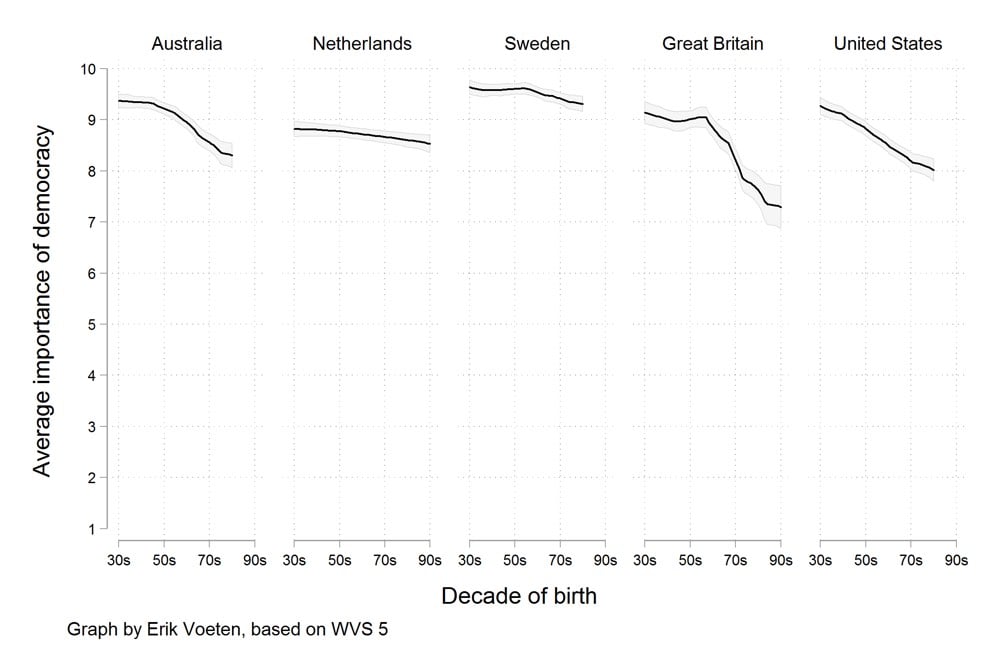

Here’s a less misleading graph:

The kicker?

Vast majorities of younger people in the West still attach great importance to living in a democracy.

Stay Connected