Wesley Morris unsurprisingly has written a very good essay about Bill Cosby — specifically, the ways in which Cosby created and blended his own persona along with that of his signature character Cliff Huxtable. He did this to root himself in America’s psychological life, and to make himself indispensable in the entertainment industry, both of which shielded him for many years from the consequences of his crimes. It was, as Morris says, Cosby’s “sickest joke.”

Bill Cosby was good at his job. That sums up why the guilty verdict Thursday is depressing — depressing not for its shock but for the work the verdict now requires me to do. The discarding and condemning and reconsidering — of the shows, the albums, the movies. But I don’t need to watch them anymore. It’s too late. I’ve seen them. I’ve absorbed them. I’ve lived them. I’m a black man, so I am them.

There’s a strange connection between serial abusers and auteurism. People take advantage of power in lots of different ways, and one of them is to assume credit for other people’s work — if not outright, than by insinuation. Cosby and Woody Allen are the two most extreme types: they worked to make themselves inseparable from the art they associated themselves with, in a way that both attracted talented collaborators and sponged credit away from them.

If I could exorcize Cosby from The Cosby Show and retain Phylicia Rashad’s performances forever, or Woody Allen from Annie Hall and do the same for Gordon Willis’s photography, I would. Part of the sick joke is that you can’t. At the same time, I don’t want to give them up. I don’t want to lose Joan Rivers’s amazing turn on Louie just because that scene (where Louis CK ends up trying to force a kiss on Joan) seems extra gross now. It’s already been ingested; it can’t easily be carved out.

This is why I sometimes say: burn the monster, and steal their jokes. This is the punishment for their years of abuse, of lies, of intimidation, of fraud: the work they made is forfeit. Cosby loses all credit for making The Cosby Show; Allen all credit for his films; it is as if they were written/produced/directed by ghosts. All credit goes to the geniuses they reeled in as unwitting collaborators, without whom they would have always been sad, useless men.

It doesn’t completely work. It doesn’t stop money flowing into their pockets, as a boycott might. It doesn’t stop you from getting angry when you see their stupid faces, as avoiding their work might. But in the handful of cases where the art is so constitutive that you can’t avoid it, it’s a fiction that helps preserve some fraction of the joy it used to. At any rate, it’s the bargain I’ve struck.

Filmmaker Robert Weide asks Woody Allen 12 questions that he’s never been asked before.

I am surprised that he would choose sporting events over movies, but as he says, he’s seen ‘em all at this point. Weide directed the excellent documentary on Allen, which is available on DVD or streaming at Amazon. (via viewsource)

Scouting NY takes a look at some filming locations used by Woody Allen for Annie Hall to see how they’ve changed in the past 36 years.

The most unexpected thing about looking at old photos of NYC is how many fewer trees there were than there are now. (via ★spavis)

Journalist William Zinsser played a bit part in Stardust Memories, one of Woody Allen’s early films. He’d interviewed Allen early in the director’s career, ran into him in NYC, and got a call a week later from his assistant.

“Bill, honey?” said a young woman’s voice. “This is Sandra from Woody Allen’s office. Woody wondered if you’d like to be in his new movie.”

That was something new in phone calls. I had never done any acting or dreamed any theatrical dreams. But who didn’t want to be in a Woody Allen movie? I knew that he often cast ordinary people in small roles. What small plum did he have for me? I hesitated for a decently modest moment and then told Sandra I’d like to do it.

“Good,” she said. “Woody will be very pleased.” She said that someone else would be calling me with further details.

(via @coudal)

This is so perfectly in the kottke.org wheelhouse that I can’t even tell if it’s any good or not: a mashup of Jay-Z and Kanye’s N***as in Paris and Woody Allen’s Midnight in Paris.

(via ★davidfg)

American Masters is airing a two-part documentary on Woody Allen this week on PBS.

Beginning with Allen’s childhood and his first professional gigs as a teen — furnishing jokes for comics and publicists — American Masters — Woody Allen: A Documentary chronicles the trajectory and longevity of Allen’s career: from his work in the 1950s-60s as a TV scribe for Sid Caesar, standup comedian and frequent TV talk show guest, to a writer-director averaging one film-per-year for more than 40 years.

The first part aired last night (it’s rerunning throughout the week so check listings, etc.) and the second part is tonight.

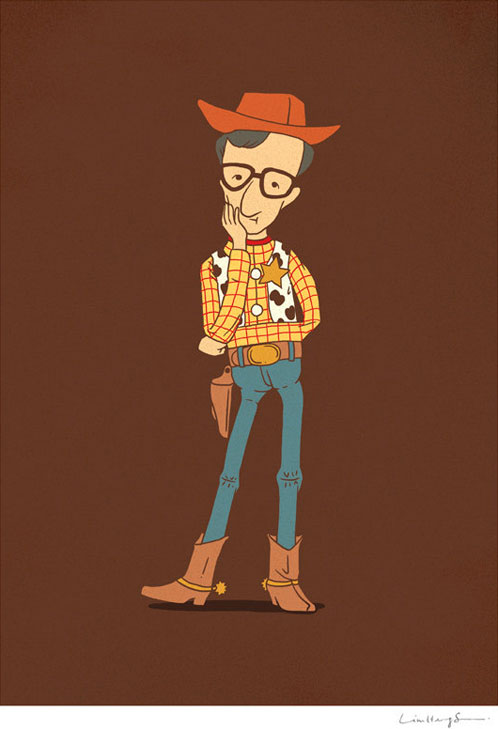

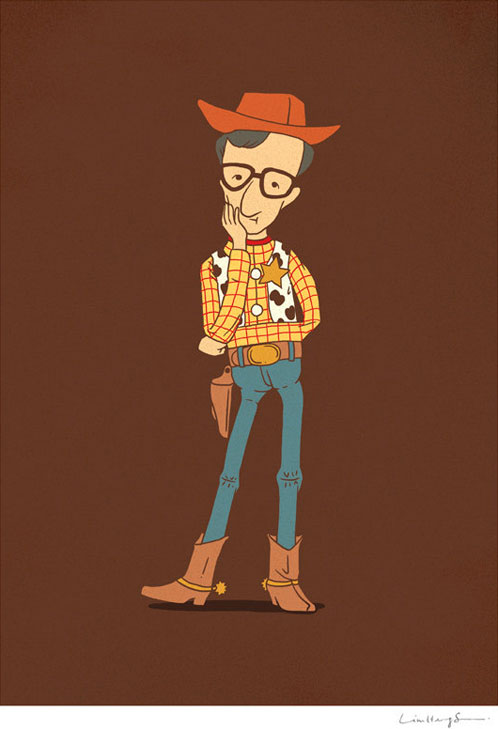

From artist Lim Heng Swee. Grab a print at Etsy while you can.

Fun fact: Tom Hanks does the voice for Woody in the movies but in most other media, he’s voiced by Tom’s younger brother Jim Hanks.

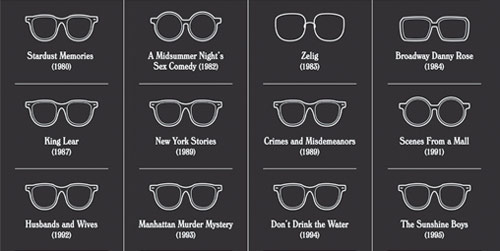

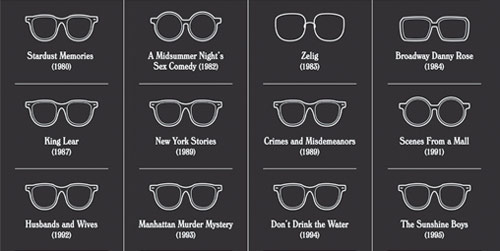

A selection of Woody’s movie eyewear from the full poster.

(thx, ben)

They are: Purple Rose of Cairo, Match Point, Bullets Over Broadway, Zelig, Husbands and Wives, and Vicky Cristina Barcelona. As Ebert said, “wrong”.

A young-ish Christopher Walken appears in Annie Hall but his name is misspelled in the credits as “Christopher Wlaken”. Were this 1990, I might have invented a eastern European backstory for Wlaken, who, perhaps, Americanized his name sometime after appearing in the film. But as we live in the future, a cool hunk of glass and metal from my pocket told me — before the credits even finished rolling — that the actor was born Ronald Walken in Astoria, Queens.

The future isn’t any fun sometimes.

Socials & More