kottke.org posts about Oliver Burkeman

Several years ago in the Guardian, Oliver Burkeman wrote a piece called This column will change your life: Helsinki Bus Station Theory. It’s about how difficult it can be as a creative person to find your way to making work that feels like it’s uniquely yours.

There are two dozen platforms, Minkkinen explains, from each of which several different bus lines depart. Thereafter, for a kilometre or more, all the lines leaving from any one platform take the same route out of the city, making identical stops. “Each bus stop represents one year in the life of a photographer,” Minkkinen says. You pick a career direction — maybe you focus on making platinum prints of nudes — and set off. Three stops later, you’ve got a nascent body of work. “You take those three years of work on the nude to [a gallery], and the curator asks if you are familiar with the nudes of Irving Penn.” Penn’s bus, it turns out, was on the same route. Annoyed to have been following someone else’s path, “you hop off the bus, grab a cab… and head straight back to the bus station, looking for another platform”. Three years later, something similar happens. “This goes on all your creative life: always showing new work, always being compared to others.” What’s the answer? “It’s simple. Stay on the bus. Stay on the fucking bus.”

(via phil gyford)

For the past decade, Oliver Burkeman has written an advice column for The Guardian on how to change your life. In his final column, he shares eight things that he’s learned while on the job. I especially appreciated these two:

When stumped by a life choice, choose “enlargement” over happiness. I’m indebted to the Jungian therapist James Hollis for the insight that major personal decisions should be made not by asking, “Will this make me happy?”, but “Will this choice enlarge me or diminish me?” We’re terrible at predicting what will make us happy: the question swiftly gets bogged down in our narrow preferences for security and control. But the enlargement question elicits a deeper, intuitive response. You tend to just know whether, say, leaving or remaining in a relationship or a job, though it might bring short-term comfort, would mean cheating yourself of growth.

The future will never provide the reassurance you seek from it. As the ancient Greek and Roman Stoics understood, much of our suffering arises from attempting to control what is not in our control. And the main thing we try but fail to control — the seasoned worriers among us, anyway — is the future. We want to know, from our vantage point in the present, that things will be OK later on. But we never can. (This is why it’s wrong to say we live in especially uncertain times. The future is always uncertain; it’s just that we’re currently very aware of it.)

It’s freeing to grasp that no amount of fretting will ever alter this truth. It’s still useful to make plans. But do that with the awareness that a plan is only ever a present-moment statement of intent, not a lasso thrown around the future to bring it under control. The spiritual teacher Jiddu Krishnamurti said his secret was simple: “I don’t mind what happens.” That needn’t mean not trying to make life better, for yourself or others. It just means not living each day anxiously braced to see if things work out as you hoped.

(via @legalnomads)

In The Guardian, Oliver Burkeman writes about the benefits of time-shifting your news reading.

One excellent way to stay calm but well-informed, I’ve found, is to consume the news a day or three later than everyone else. Print is one way to do this. But it works online, too: more and more, I find myself promiscuously cruising the web, saving umpteen articles in a “read later” app (in my case Evernote, though you could use your browser’s bookmarks). By the time I read them, the time filter has worked its magic: a small proportion of them stand out as truly compelling.

A new car loses about 10% of its value as soon as you drive it off the lot; most news depreciates a lot faster than that. Humans are curious, hard-wired to seek out new information on a continuous basis. But not everything we haven’t seen before is worth our attention. As Burkeman says, a great way to determine if something is intrinsically interesting or worthwhile apart from its novelty is to set it aside for awhile.

My process for gathering links and information for kottke.org is pretty much what Burkeman outlines in the article: when I see something that looks interesting, I file it away and revisit it later. I don’t even leave it that long sometimes…even a few hours works wonders. Most of the links I throw out, some because they weren’t as interesting as I’d hoped from reading a headline or pull quote but more often because they won’t be interesting after a day or two passes. I’m proud that you can go back weeks, months, years, and (more rarely) decades into the kottke.org archives and still find things worth your time.

In recent years, commentators like Max Roser, Steven Pinker, Nicholas Kristof, and Matt Ridley have argued contrary to the prevailing mood that our world increasingly resembles a dumpster fire, things have actually never been better. Here’s Kristof for instance arguing that 2017 will likely be the best year in the history of the world:

Every day, an average of about a quarter-million people worldwide graduate from extreme poverty, according to World Bank figures.

Or if you need more of a blast of good news, consider this: Just since 1990, more than 100 million children’s lives have been saved through vaccinations, breast-feeding promotion, diarrhea treatment and more. If just about the worst thing that can happen is for a parent to lose a child, that’s only half as likely today as in 1990.

In a long piece for The Guardian, Oliver Burkeman does not dispute that the world’s population is better off than it was 200 years by any number of metrics. But he does argue that this presumably bias-free examination of the facts is also a political argument with several implications and assumptions.

But the New Optimists aren’t primarily interested in persuading us that human life involves a lot less suffering than it did a few hundred years ago. (Even if you’re a card-carrying pessimist, you probably didn’t need convincing of that fact.) Nestled inside that essentially indisputable claim, there are several more controversial implications. For example: that since things have so clearly been improving, we have good reason to assume they will continue to improve. And further — though this is a claim only sometimes made explicit in the work of the New Optimists — that whatever we’ve been doing these past decades, it’s clearly working, and so the political and economic arrangements that have brought us here are the ones we ought to stick with. Optimism, after all, means more than just believing that things aren’t as bad as you imagined: it means having justified confidence that they will be getting even better soon.

What things are like right now are the result of past actions. But the world to come is the result of what’s happening right now and what will happen in the next few years. Momentum (mass times velocity) is a powerful thing in a big world, but it’s not everything. It’s a bit like saying “ok, we’ve got the car up to speed” then letting up on the gas and expecting to continue to accelerate.

The New Optimists “describe a world in which human agency doesn’t seem to matter, because there are these evolved forces that are moving us in the right direction,” Runciman says. “But human agency does still matter… human beings still have the capacity to mess it all up. And it may be that our capacity to mess it up is growing.”

And just because things are good now doesn’t mean they couldn’t be better or start heading in the other direction soon.

But after steeping yourself in their work, you begin to wonder if all their upbeat factoids really do speak for themselves. For a start, why assume that the correct comparison to be making is the one between the world as it was, say, 200 years ago, and the world as it is today? You might argue that comparing the present with the past is stacking the deck. Of course things are better than they were. But they’re surely nowhere near as good as they ought to be. To pick some obvious examples, humanity indisputably has the capacity to eliminate extreme poverty, end famines, or radically reduce human damage to the climate. But we’ve done none of these, and the fact that things aren’t as terrible as they were in 1800 is arguably beside the point.

Read the whole thing…it’s a solid defense against a sentiment I find increasingly irksome.

You could argue that the world has never been better: war is increasingly rare, medical science has cured a number of the deadliest diseases, global poverty is down, life expectancy is up, and crime in America is down. But it sure doesn’t seem that way, especially with Brexit, climate change, Trump, Syria, and terrorist incidents around the world. Oliver Burkeman explores some of the reasons why we think the sky is continually falling and what we can do to be happy anyway. I have been thinking about this aspect of it recently:

And there is another, subtler reason you might find yourself convinced that things are getting worse and worse, which is that our expectations outpace reality. That is, things do improve — but we raise our expectations for how much better they ought to be at a faster rate, creating the illusion that progress has gone into reverse.

See also George Saunders’ manifesto from People Reluctant To Kill for an Abstraction.

Jason Fried, founder of 37signals (which became Basecamp a few years back) writes about not having goals.

I can’t remember having a goal. An actual goal.

There are things I’ve wanted to do, but if I didn’t do them I’d be fine with that too. There are targets that would have been nice to hit, but if I didn’t hit them I wouldn’t look back and say I missed them.

I don’t aim for things that way.

I do things, I try things, I build things, I want to make progress, I want to make things better for me, my company, my family, my neighborhood, etc. But I’ve never set a goal. It’s just not how I approach things.

A goal is something that goes away when you hit it. Once you’ve reached it, it’s gone. You could always set another one, but I just don’t function in steps like that.

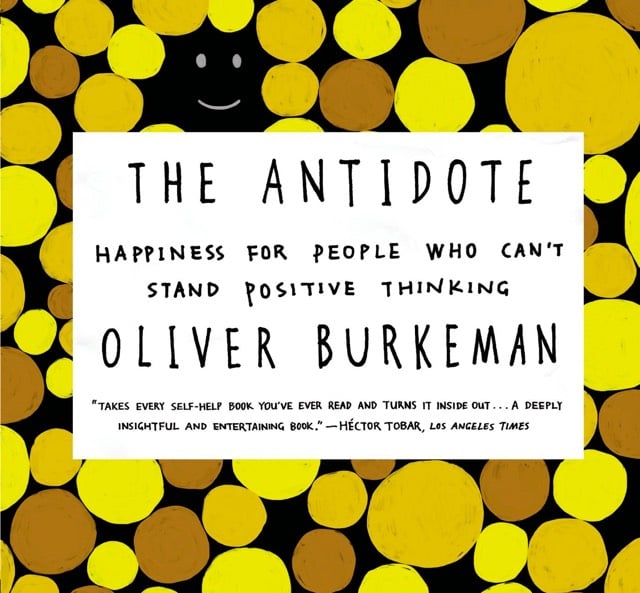

This is my exact approach, which can drive the more goal oriented people in your life a little bit nuts. Oliver Burkeman wrote about goals being potentially counter-productive in The Antidote, which is perhaps the book I’ve thought most about over the past year. An excerpt from the book about goals was published as a piece for Fast Company.

It turns out, however, that setting and then chasing after goals can often backfire in horrible ways. There is a good case to be made that many of us, and many of the organizations for which we work, would do better to spend less time on goalsetting, and, more generally, to focus with less intensity on planning for how we would like the future to turn out.

One illuminating example of the problem concerns the American automobile behemoth General Motors. The turn of the millennium found GM in a serious predicament, losing customers and profits to more nimble, primarily Japanese, competitors. As the Boston Globe reported, executives at GM’s headquarters in Detroit came up with a goal, crystallized in a number: 29. Twenty-nine, the company announced amid much media fanfare, was the percentage of the American car market that it would recapture, reasserting its old dominance. Twenty-nine was also the number displayed upon small gold lapel pins, worn by senior figures at GM to demonstrate their commitment to the plan. At corporate gatherings, and in internal GM documents, twenty-nine was the target drummed into everyone from salespeople to engineers to public-relations officers.

Yet the plan not only failed to work-it made things worse. Obsessed with winning back market share, GM spent its dwindling finances on money-off schemes and clever advertising, trying to lure drivers into purchasing its unpopular cars, rather than investing in the more speculative and open-ended-and thus more uncertain-research that might have resulted in more innovative and more popular vehicles.

Update: Forgot to add: For the longest time, I thought I was wrong to not have goals. Setting goals is the only way of achieving things, right? When I was criticizing my goalless approach to my therapist a few years ago, he looked at me and said, “It seems like you’ve done pretty well for yourself so far without worrying about goals. That’s just the way you are and it’s working for you. You don’t have to change.” That was a huge realization for me and it’s really helped me become more comfortable with my approach.

In the Guardian, Oliver Burkeman writes about what’s going on when we become a little stubborn about not wanting to enjoy Hamilton, Ferrante, Better Call Saul, or [insert your friends’ current cultural obsession here].

Somewhere around the 500th headline I read in praise of Hamilton, the universally acclaimed Broadway musical due in Europe next year, I was struck by a deflating thought: I’ll probably never see it. Not just because it’s virtually impossible to get a ticket, but because so many people — people whose tastes I trust — have raved about it that I now regard the prospect with annoyance. Two years ago, it was the Richard Linklater movie Boyhood, which I still haven’t seen; then Elena Ferrante’s Neapolitan novels, which I still haven’t read. Straw polls of friends suggest I’m not alone in this reaction — call it “cultural cantankerousness” — which seems to affect books, films, plays, holiday destinations and restaurants equally. Increasingly, my first thought on seeing something described as a “must-read” is‘“Oh really? Try and make me.”

This reaction could be a FOMO defense, but the optimal distinctiveness theory explanation is more interesting.

One explanation is what psychologists call “optimal distinctiveness theory” — the way we’re constantly jockeying to feel exactly the right degree of similarity to and difference from those around us. Nobody wants to be exiled from the in-group to the fringes of society; but nobody wants to be swallowed up by it, either.

FWIW, I have not see Boyhood or Better Call Saul yet, but I’ve read Ferrante and seen Hamilton are both are as good as advertised. (Oh, and Burkeman’s own book, The Antidote, is great as well.)

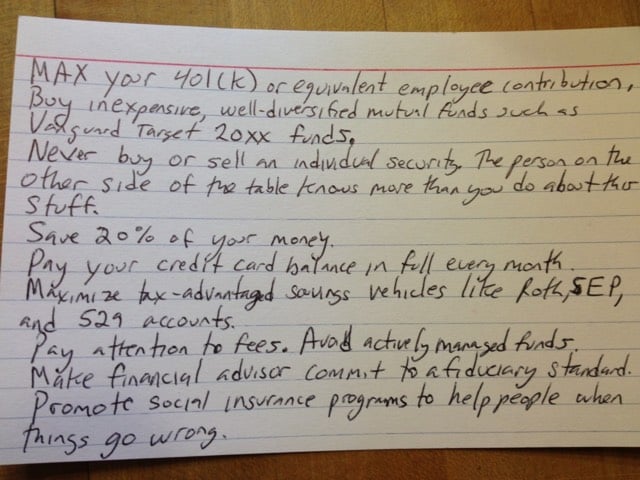

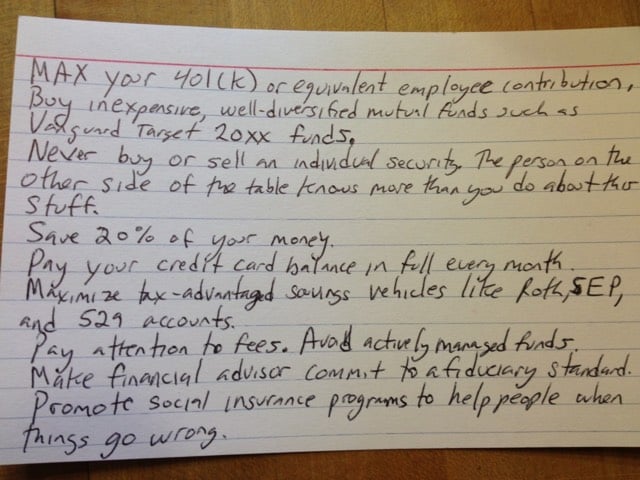

The Index Card is a new book by Helaine Olen and Harold Pollack about simple advice for personal finance. The idea for the book came about when Pollack jotted down financial advice that works for almost everyone on a 4x6 index card.

Now, Pollack teams up with Olen to explain why the ten simple rules of the index card outperform more complicated financial strategies. Inside is an easy-to-follow action plan that works in good times and bad, giving you the tools, knowledge, and confidence to seize control of your financial life.

I learned about their book from a piece by Oliver Burkeman on why complex questions can have simple answers.

But there’s a powerful truth here, which is that people dispensing financial advice are even less neutral than we realise. We’re good at spotting the obvious conflicts of interest: of course mortgage providers always think it’s a great time to buy a house; of course the sharp-suited guys from SpeedyMoola.co.uk think their payday loans are good value. But it’s more difficult to see that everyone offering advice has a deeper vested interest: they need you to believe things are complex enough to make their assistance worthwhile. It’s hard to make a living as a financial adviser by handing clients an index card and telling them never to return; and those stock-tipping columns in newspapers would be dull if all they ever said was “ignore stock tips”. Yes, the world of finance is complex, but it doesn’t follow that you need a complex strategy to navigate it.

There’s no reason to assume this situation only occurs with money, either. The human body is another staggeringly complex system, but based on current science, Michael Pollan’s seven-word guidance — “Eat food, not too much, mostly plants” — is probably wiser than all other diets.

Burkeman wrote one of my favorite books from the past year, The Antidote: Happiness for People Who Can’t Stand Positive Thinking.

From the abstract of a paper on the relationship between impatience and procrastination, this caught my eye:

We find substantial evidence of time inconsistency. Namely, more that half of the participants who receive their check straight away instead of waiting two weeks for a reasonably larger amount, subsequently take more than two weeks to cash it.

This reminded me of a passage I read recently in Oliver Burkeman’s The Antidote1 about the pitfalls of positive visualization.

Yet there are problems with this outlook, aside from just feeling disappointed when things don’t turn out well. These are particularly acute in the case of positive visualisation. Over the last few years, the German-born psychologist Gabriele Oettingen and her colleagues have constructed a series of experiments designed to unearth the truth about ‘positive fantasies about the future’. The results are striking: spending time and energy thinking about how well things could go, it has emerged, actually reduces most people’s motivation to achieve them. Experimental subjects who were encouraged to think about how they were going to have a particularly high-achieving week at work, for example, ended up achieving less than those who were invited to reflect on the coming week, but given no further guidelines on how to do so.

In one ingenious experiment, Oettingen had some of the participants rendered mildly dehydrated. They were then taken through an exercise that involved visualising drinking a refreshing, icy glass of water, while others took part in a different exercise. The dehydrated water-visualisers — contrary to the self-help doctrine of motivation through visualisation — experienced a significant reduction in their energy levels, as measured by blood pressure. Far from becoming more motivated to hydrate themselves, their bodies relaxed, as if their thirst were already quenched. In experiment after experiment, people responded to positive visualisation by relaxing. They seemed, subconsciously, to have confused visualising success with having already achieved it.

In a similar way, it may be that the people who received their checks right away but didn’t cash them “relaxed” as though they had actually spent the money, not just gotten the check. (via mr)

“Success through failure, calm through embracing anxiety…” This book sounds perfect for me. The Antidote: Happiness for People Who Can’t Stand Positive Thinking by Oliver Burkeman.

Self-help books don’t seem to work. Few of the many advantages of modern life seem capable of lifting our collective mood. Wealth — even if you can get it — doesn’t necessarily lead to happiness. Romance, family life, and work often bring as much stress as joy. We can’t even agree on what “happiness” means. So are we engaged in a futile pursuit? Or are we just going about it the wrong way?

Looking both east and west, in bulletins from the past and from far afield, Oliver Burkeman introduces us to an unusual group of people who share a single, surprising way of thinking about life. Whether experimental psychologists, terrorism experts, Buddhists, hardheaded business consultants, Greek philosophers, or modern-day gurus, they argue that in our personal lives, and in society at large, it’s our constant effort to be happy that is making us miserable. And that there is an alternative path to happiness and success that involves embracing failure, pessimism, insecurity, and uncertainty — the very things we spend our lives trying to avoid. Thought-provoking, counterintuitive, and ultimately uplifting, The Antidote is the intelligent person’s guide to understanding the much-misunderstood idea of happiness.

I learned about the book from Tyler Cowen, who notes:

[Burkeman] is one of the best non-fiction essay writers, and he remains oddly underrated in the United States. It is no mistake to simply buy his books sight unseen. I think of this book as “happiness for grumps.”

Given Cowen’s recent review of Inside Out, I wonder if [slight spoilers ahoy!] he noticed the similarity of Joy’s a-ha moment w/r/t to Sadness at the end of the film to the book’s “alternative path to happiness and success that involves embracing failure, pessimism, insecurity, and uncertainty”. Mmmm, zeitgeisty!

Stay Connected