While exploring the ground underneath the ancient Mayan city of Chichén Itzá in Mexico, archaeologists found a ritual chamber stuffed with artifacts untouched for more than 1000 years.

De Anda recalls pulling himself on his stomach through the tight tunnels of Balamku for hours before his headlamp illuminated something entirely unexpected: A cascade of offerings left by the ancient residents of Chichén Itzá, so perfectly preserved and untouched that stalagmites had formed around the incense burners, vases, decorated plates, and other objects in the cavern.

“I couldn’t speak, I started to cry. I’ve analyzed human remains in [Chichén Itzá’s] Sacred Cenote, but nothing compares to the sensation I had entering, alone, for the first time in that cave,” says de Anda, who is an investigator with INAH and director of the Great Maya Aquifer Project, which seeks to explore, understand, and protect the aquifer of Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula.

“You almost feel the presence of the Maya who deposited these things in there,” he adds.

Oddly, the cave was explored by an archaeologist back in 1966, but he ordered the entrance sealed up and the chamber and the objects contained within were forgotten until now.

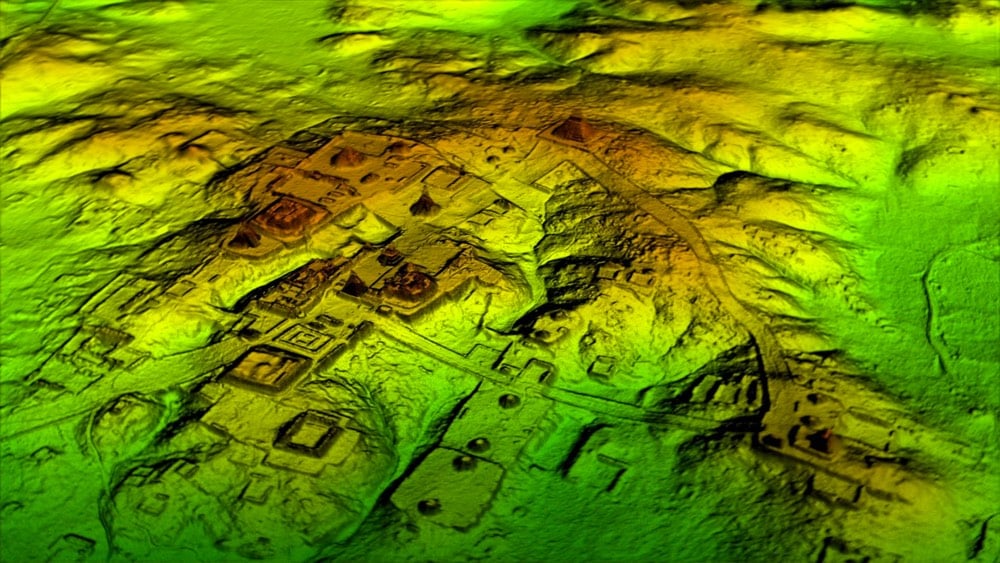

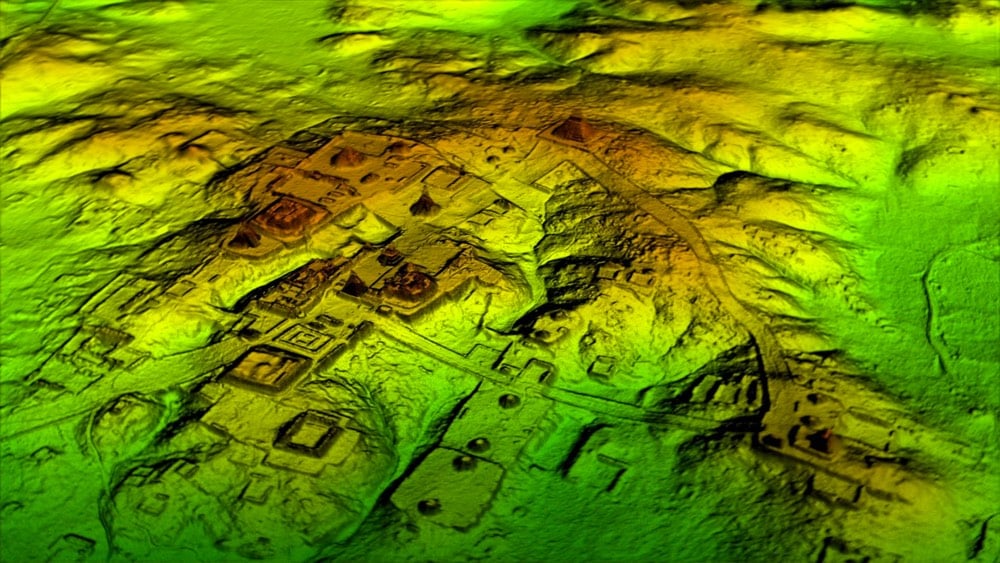

Using LIDAR, a team of researchers in Guatemala has been able to peer underneath the dense jungle to see what the landscape looked like in the time of the Mayans, a civilization which reached its peak between 250-900 A.D. — an x-ray of the forest, if you will. The results are astonishing…they reveal a civilization much larger and more sophisticated than previously thought.

The results suggest that Central America supported an advanced civilization that was, at its peak some 1,200 years ago, more comparable to sophisticated cultures such as ancient Greece or China than to the scattered and sparsely populated city states that ground-based research had long suggested.

In addition to hundreds of previously unknown structures, the LiDAR images show raised highways connecting urban centers and quarries. Complex irrigation and terracing systems supported intensive agriculture capable of feeding masses of workers who dramatically reshaped the landscape.

The potential of LIDAR as a cultural and geological time machine is just starting to be realized. You might remember these LIDAR images of the geology of forested areas in Washington State.

Update: Another team, working in Mexico, recently used LIDAR to uncover a city built by the Purépecha civilization that had as many buildings as modern-day Manhattan.

15-year-old Canadian William Gadoury has translated his interest in the Mayan civilization into two remarkable discoveries. Gadoury noticed that the locations of the biggest Mayan cities matched the locations of the stars in Mayan constellations. Furthermore, the star charts pointed to the existence of a previously unknown city, the ruins of which have since been uncovered by satellite photography.

“I did not understand why the Maya built their cities away from rivers, on marginal lands and in the mountains,” said Gadoury. “They had to have another reason, and as they worshiped the stars, the idea came to me to verify my hypothesis. I was really surprised and excited when I realized that the most brilliant stars of the constellations matched the largest Maya cities.”

Someone start a Kickstarter campaign so that he can visit those ruins! (via @delfuego)

Update: Due to a mislabeled file on Wikipedia, I used a photo of an Aztec compass instead of a Mayan image. I have replaced with an image of the Mayan zodiac.

Also, per my post about media coverage of science yesterday, I’ll point out quickly that there’s much to be skeptical about re: this story (see this post from a Mesoamerican archaeologist). More likely than not, there’s a Mayan scholar mailing list going bananas right now…I’ll let you know if I hear anything specific.

In the meantime, this story in the Independent contains some satellite photos of the location in question. (via @gunnihinn)

Update: Vice: That 15-Year-Old Kid Probably Didn’t Discover a Hidden Mayan City.

The rectangular feature seen on satellite is likely an old corn field (it’s not the right shape to be a pyramid). There are indeed ancient Maya sites all over the place, and satellite imagery and LiDAR are being used to discover them, but this doesn’t seem to be one of those cases…

On the bright side, the “if it sounds too good to be true, it probably is” study has been successfully replicated again. Science rolls on…

A team of archeologists used aircraft-mounted LIDAR (a laser-based distance measuring system) to map the Mayan ruins of Caracol. The imaging revealed more of the ruins in four days than on-the-ground teams have been able to do in the past 25 years.

The Chases, who are professors of anthropology at the University of Central Florida in Orlando, had determined from earlier surveys that Caracol extended over a wide area in its heyday, between A.D. 550 and 900. From a ceremonial center of palaces and broad plazas, it stretched out to industrial zones and poor neighborhoods and beyond to suburbs of substantial houses, markets and terraced fields and reservoirs. This picture of urban sprawl led the Chases to estimate the city’s population at its peak at more than 115,000. But some archaeologists doubted the evidence warranted such expansive interpretations.

“Now we have a totality of data and see the entire landscape,” Dr. Arlen Chase said of the laser findings. “We know the size of the site, its boundaries, and this confirms our population estimates, and we see all this terracing and begin to know how the people fed themselves.”

Stay Connected