For his photo series The Pillar (which is also a book), Stephen Gill set up a camera next to a post near his home in Sweden and set the shutter to fire when a motion sensor was triggered. “I decided to try to pull the birds from the sky,” he said.

A selection of Gill’s photographs were published by the New Yorker, accompanied by a wonderful short essay by Karl Ove Knausgaard.

A pillar knocked into the ground next to a stream in a flat, open landscape, trees and houses visible in the distance, beneath a vast sky. That is the backdrop to all the photographs in Stephen Gill’s book “The Pillar.” We see the same landscape in spring and summer, in autumn and winter, we see it in sunshine and rain, in snow and wind. Yet there is not the slightest bit of monotony about these pictures, for in almost every one there is a bird, and each of these birds opens up a unique moment in time. We see something that has never happened before and will never happen again. The first time I looked at the photographs, I was shaken. I’d never seen birds in this way before, as if on their own terms, as independent creatures with independent lives.

Karl Ove Knausgaard is writing a series of four books, one for each one of the seasons. The first one, Autumn, just came out yesterday.

Autumn begins with a letter Karl Ove Knausgaard writes to his unborn daughter, showing her what to expect of the world. He writes one short piece per day, describing the material and natural world with the precision and mesmerising intensity that have become his trademark. He describes with acute sensitivity daily life with his wife and children in rural Sweden, drawing upon memories of his own childhood to give an inimitably tender perspective on the precious and unique bond between parent and child. The sun, wasps, jellyfish, eyes, lice—the stuff of everyday life is the fodder for his art. Nothing is too small or too vast to escape his attention. This beautifully illustrated book is a personal encyclopaedia on everything from chewing gum to the stars. Through close observation of the objects and phenomena around him, Knausgaard shows us how vast, unknowable and wondrous the world is.

Ah, so that’s what the chewing gum thing was about. The NY Times review is positive overall with a few caveats. The Times also did a By the Book with Knausgaard in which he shares “books I want to read, books I have to read and books I believe I need to read […] we are talking about id, ego and superego books”. Among his book picks are Pond by Claire-Louise Bennett and The Brain: The Story of You by David Eagleman. There is also this:

I hardly ever laugh.

LOL Knausgaard.

While he’s working, Karl Ove Knausgaard chews gum and lots of it.

From a purely physiological perspective, chewing something without swallowing is pointless. So is smoking cigarettes, but when you smoke, the cigarette releases stimulating and addictive substances, which explains why fully grown adults suck on them. Gum does not produce any such effects. Its pleasure is more closely related to that of the pacifiers that infants suck on, where the sucking reflex first tricks the body into believing that it is working at getting itself some food, then takes over entirely and turns sucking on something into an activity that is valuable in and of itself. It is obvious, then, that there is something infantile about chewing gum.

I would love to see 4-5 paragraphs about him trying the gum from a pack of 1989 Topps baseball cards for the first time. Just thinking about it makes me gag.

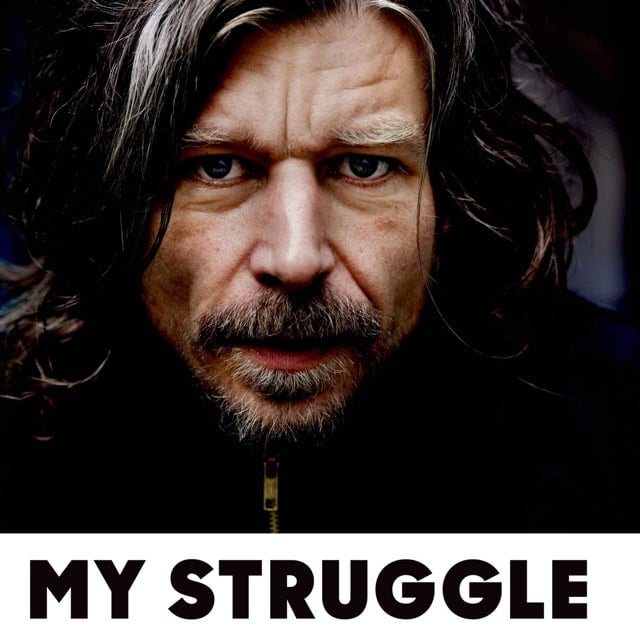

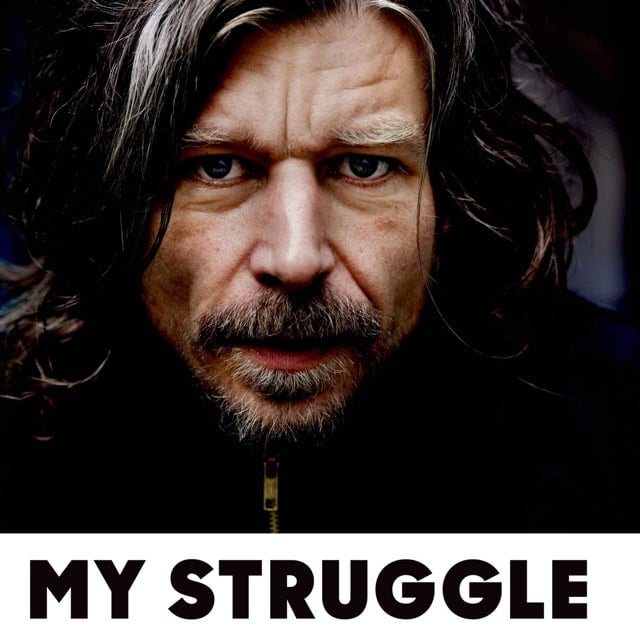

The New Yorker has an excerpt of the fourth volume of Karl Ove Knausgaard’s My Struggle.

Throughout our childhood we three had sat chatting, that was what I was used to, but this was the first time we had done it without Dad living in the house, and the difference was immense. Knowing that he couldn’t walk in at any moment, forcing us to think about what we were saying and doing, changed everything.

We had chatted about everything under the sun then too, but never so much as a word about Dad, it was a kind of implicit rule.

I had never thought about that before.

But we couldn’t talk about him now, that would have been inconceivable.

Why?

The NY Times Magazine got Karl Ove Knausgaard (author of My Struggle) to “drive across America and write about it without talking to a single American”, like some sort of introverted Tocqueville. He came unprepared:

I dialed the number of the driver’s-license office at the Swedish Transport Agency, keyed in my personal identity number and sat down at the desk, scrolling through some Norwegian newspapers as I waited my turn.

A prerecorded voice came on and informed me about opening hours, then the line went dead.

What the hell?

Had they closed?

But it couldn’t be later than 1 p.m. in Sweden.

I looked at the Transport Agency website. To my dismay, I discovered that it was a holiday in Sweden tomorrow, Trettondagsafton, the Feast of the Epiphany, and a half-day today.

That meant I couldn’t get the driver’s-license confirmation letter until three days from now at the earliest, more likely four.

Oh, no.

I wasn’t even in the U.S. yet, I was just in Canada!

I lay back in bed and stared at the ceiling. I should email The Times and explain the situation. Maybe they had a solution. But I couldn’t. I just couldn’t bring myself to tell them that I’d undertaken this great road-trip assignment across the U.S. without my license. They’d think I was a complete idiot.

In any case, there was nothing I could do today.

And his thoughts on Detroit (emphasis mine):

I’d seen poverty before, of course, even incomprehensible poverty, as in the slums outside Maputo, in Mozambique. But I’d never seen anything like this. If what I had seen tonight - house after house after house abandoned, deserted, decaying as if there had been disaster - if this was poverty, then it must be a new kind poverty, maybe in the same way that the wealth that had amassed here in the 20th century had been a new kind of wealth. I had never really understood how a nation that so celebrated the individual could obliterate all differences the way this country did. In a system of mass production, the individual workers are replaceable and the products are identical. The identical cars are followed by identical gas stations, identical restaurants, identical motels and, as an extension of these, by identical TV screens, which hang everywhere in this country, broadcasting identical entertainment and identical dreams. Not even the Soviet Union at the height of its power had succeeded in creating such a unified, collective identity as the one Americans lived their lives within. When times got rough, a person could abandon one town in favor of another, and that new town would still represent the same thing.

Was that what home was here? Not the place, not the local, but the culture, the general?

Update: The Times has posted the second part of Knausgaard’s My Saga.

If there is something to be gained, if it is gainable, no power on earth can restrain the forces that seek to gain it. To leave a profit or a territory or any kind of resource, even a scientific discovery, unexploited is deeply alien to human nature.

The English translation of the fourth volume of Karl Ove Knausgaard’s epic My Struggle is coming out in April.

At eighteen years, old Karl Ove moves to a tiny fisherman’s village in the far north of the arctic circle to work as a school teacher. No interest in the job itself, his intention is to save up enough money to travel while finding the space and time to start his writing career. Initially everything looks fine. He writes his first few short stories, finds himself accepted by the hospitable locals, and receives flattering attention from several beautiful local girls. But as the darkness of the long arctic nights start to consume the landscape, Karl Ove’s life takes a darker turn.

It looks like an alternate translation of the book will be out in the UK in March in case you want to get a head start on everyone else. Or there’s always Norwegian lessons…the sixth and final volume was published in Norway in 2011.

Book 1 of Karl Ove Knausgaard’s epic My Struggle is now available in English as an audiobook. This was by far my favorite book of 2014…the first 50 pages punched me in the gut about 10 times and the rest did not disappoint. After a bit of a break to recover, I am looking forward to tackling Book 2 & Book 3 in the next couple of months. (via @tylercowen)

Socials & More