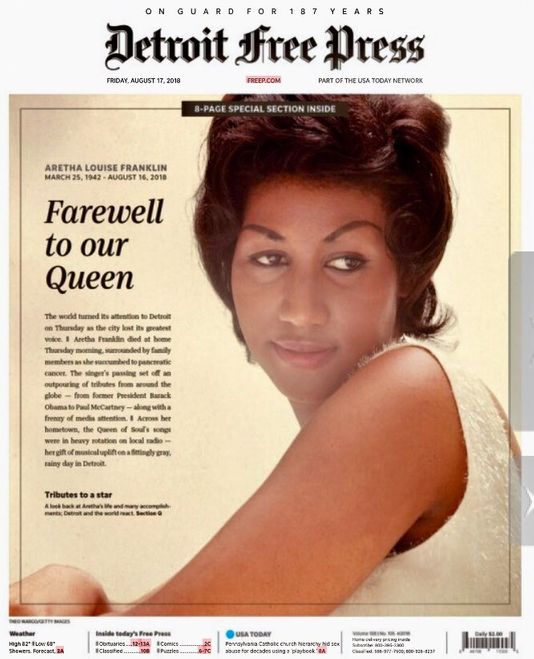

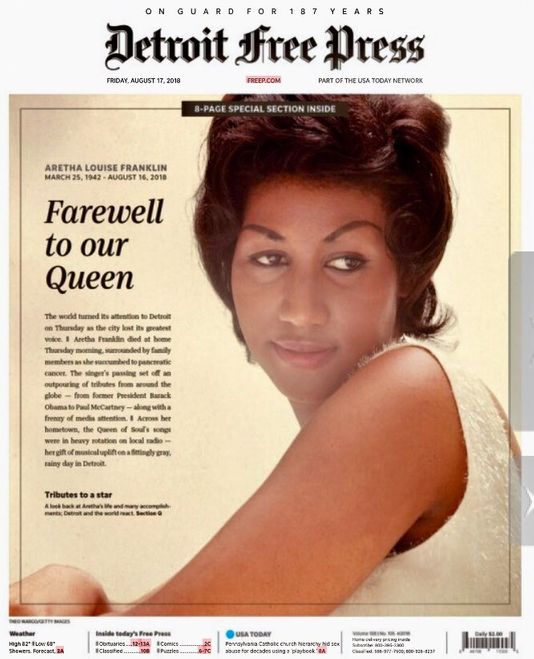

There are many very fine obituaries and appreciations of Aretha Franklin, who passed away this week at 76. I have two favorites.

The first is a whip-crack of an essay by the New York Times’s Wesley Morris that, better than most, taps into Franklin’s own musical energies.

Ms. Franklin’s respect lasts for two minutes and 28 seconds. That’s all — basically a round of boxing. Nothing that’s over so soon should give you that much strength. But that was Aretha Franklin: a quick trip to the emotional gym. Obviously, she was far more than that. We’re never going to have an artist with a career as long, absurdly bountiful, nourishing and constantly surprising as hers. We’re unlikely to see another superstar as abundantly steeped in real self-confidence — at so many different stages of life, in as many musical genres….

The song owned the summer of 1967. It arrived amid what must have seemed like never-ending turmoil — race riots, political assassinations, the Vietnam draft. Muhammad Ali had been stripped of his championship title for refusing to serve in the war. So amid all this upheaval comes a singer from Detroit who’d been around most of the decade doing solid gospel R&B work. But there was something about this black woman’s asserting herself that seemed like a call to national arms. It wasn’t a polite song. It was hard. It was deliberate. It was sure.

The second essay, for NPR by dream hampton, “Black People Will Be Free’: How Aretha Lived The Promise Of Detroit,” is more slowly wound, and less about the music than the time and place that produced Franklin and in which she flourished. It bleeds like a wound, a wound the size of a city, where the Industrial Revolution met the Great Migration and became the Civil Rights Movement.

It’s impossible to talk about Aretha without talking about her father, Reverend C.L. Franklin of Detroit’s New Bethel Baptist Church. Born to Mississippi sharecroppers, Franklin began preaching and soul singing as a teenager. Just after World War II, he, like so many black Southerners who were fleeing racial terror and looking for work, found himself in Detroit. Mayor Coleman Young, Detroit’s first black mayor, called him a “preacher’s preacher.” And when Franklin died from gunshot wounds after being robbed in his home in 1979, Mayor Young said his “leadership of the historic freedom march down Woodward Avenue in Detroit with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. by his side in June of 1963 — and involving some 125,000 people — provided the prototype for Dr. King’s successful march in Washington later that summer.”

It is important to understand the tradition of black liberation theology, a term coined by James H. Cone, that sought to use scripture to center black self-determination. In Detroit, pastors like C.L. Franklin and Albert Cleage of the Shrine of the Black Madonna used black liberation theology to help a growing black city to imagine itself powerful. They used their churches to launch the campaign of Detroit’s black political class, including Coleman Young. At the same time, Rev. Franklin’s church remained a touch point for even more radical organizing. He opened New Bethel to black auto workers who were waging a class struggle within a racist United Automobile Workers union. He gave shelter to Black Panthers who were targeted by J. Edgar Hoover’s crusade against them. Later leaders of the fractured Black Power movement like the late Jackson, Miss. mayor (and Detroit native) Chokwe Lumumba gathered at New Bethel to form the Republic of New Afrika.

A new sound rooted in older sounds; a new politics rooted in older politics; a new, triumphant individualism rooted in the liberation of entire communities. In all these things, Aretha stood at the crossroads of history. Maybe no one else could have done it.

This short film by Ben Proudfoot features Melvin Dismukes, who was a private security guard during the Detroit race riot of 1967. Dismukes responded to a situation at the Algiers Motel and ended up being accused of murder, spending years trying to clear his name. In this film, Dismukes tells his story, which is intercut with scenes from Kathryn Bigelow’s Detroit, which features Star Wars’ John Boyega as Dismukes.

Dismukes also told his story to the Detroit Historical Society last year.

After getting outside there, you could hear gunfire coming from the area of the Algiers, Virginia Park area. National Guard showed up over there to find out what had happened on the corner, and they heard the shots also, so we started headed toward the Algiers, the other two guys that was working with me stayed at the store because we had to protect the store, needed somebody there. Went across the street to the Algiers, gunfire was still coming from the building, lots of gunfire, we couldn’t tell where the gunfire was really coming from. One of the policemen that was in the area with us told us to take out the streetlights. I would say I had a rifle, I didn’t have a shotgun, so the guys with the shotgun took out the streetlights. I had one guy what I thought was a sniper, because I’d seen a flash from a window in the Algiers, it was up on, I think it was the second floor. I fired at that guy, I missed the guy, that’s the only shot I fired during the whole riot, second shot I fired with the rifle. Prior to that, I fired my first day on the job on Sunday, I fired the rifle to get some people off the streets, you know, and they wouldn’t move, and they wanted to play the honky town thing, so fired the gun, the gun had never been fired before, so the barrel was full of oil, and when it went off, and there’s this dust you get flames coming out of it, and they hollered, “He’s got a flamethrower,” so they all turned around and started running.

The NY Times Magazine got Karl Ove Knausgaard (author of My Struggle) to “drive across America and write about it without talking to a single American”, like some sort of introverted Tocqueville. He came unprepared:

I dialed the number of the driver’s-license office at the Swedish Transport Agency, keyed in my personal identity number and sat down at the desk, scrolling through some Norwegian newspapers as I waited my turn.

A prerecorded voice came on and informed me about opening hours, then the line went dead.

What the hell?

Had they closed?

But it couldn’t be later than 1 p.m. in Sweden.

I looked at the Transport Agency website. To my dismay, I discovered that it was a holiday in Sweden tomorrow, Trettondagsafton, the Feast of the Epiphany, and a half-day today.

That meant I couldn’t get the driver’s-license confirmation letter until three days from now at the earliest, more likely four.

Oh, no.

I wasn’t even in the U.S. yet, I was just in Canada!

I lay back in bed and stared at the ceiling. I should email The Times and explain the situation. Maybe they had a solution. But I couldn’t. I just couldn’t bring myself to tell them that I’d undertaken this great road-trip assignment across the U.S. without my license. They’d think I was a complete idiot.

In any case, there was nothing I could do today.

And his thoughts on Detroit (emphasis mine):

I’d seen poverty before, of course, even incomprehensible poverty, as in the slums outside Maputo, in Mozambique. But I’d never seen anything like this. If what I had seen tonight - house after house after house abandoned, deserted, decaying as if there had been disaster - if this was poverty, then it must be a new kind poverty, maybe in the same way that the wealth that had amassed here in the 20th century had been a new kind of wealth. I had never really understood how a nation that so celebrated the individual could obliterate all differences the way this country did. In a system of mass production, the individual workers are replaceable and the products are identical. The identical cars are followed by identical gas stations, identical restaurants, identical motels and, as an extension of these, by identical TV screens, which hang everywhere in this country, broadcasting identical entertainment and identical dreams. Not even the Soviet Union at the height of its power had succeeded in creating such a unified, collective identity as the one Americans lived their lives within. When times got rough, a person could abandon one town in favor of another, and that new town would still represent the same thing.

Was that what home was here? Not the place, not the local, but the culture, the general?

Update: The Times has posted the second part of Knausgaard’s My Saga.

If there is something to be gained, if it is gainable, no power on earth can restrain the forces that seek to gain it. To leave a profit or a territory or any kind of resource, even a scientific discovery, unexploited is deeply alien to human nature.

Jim Griffioen took photos of every house on a block in Detroit where most of the houses are abandoned and stitched them into panoramas.

If you were to compare the current international housing crisis to a black hole sucking the equity out of our homes, this one-way street near the northern border of Detroit might just be the singularity: the point where the density of the problem defies anyone’s ability to comprehend it. These homes started emptying in 2006.

(via greg.org)

The ruins of Detroit, a series of photos by Yves Marchand & Romain Meffre documenting vacant buildings in Detroit. Some of the photos are repeated with useful annotation in this Time photo gallery. (See also Brian Ulrich’s Stores That Are No More.)

On the other hand, some are arguing that there is great opportunity in Detroit right now.

Detroit right now is just this vast, enormous canvas where anything imaginable can be accomplished.

Stay Connected