Emily Wilson, who produced this banging translation of The Odyssey and is currently at work on The Iliad, recently tweeted a list of “reasons why it’s more or less impossible to translate Homer into English in a satisfactory way”. Here are a few of those reasons:

2. There aren’t enough onomatopoeic words for very loud chaotic noises.

3. “Many”, especially when repeated over and over, sounds childish; repeating “lots of” sounds worse. There are not enough words for large numbers of people or objects, and those we have (“multitude”, “plethora”, “myriad”) are often too pompous to use repeatedly.

6. Terms for social rank imply a particular wrong social order. “King” suggests monarchy. “Chief” has several connotations, none quite right. “General”, “Marshal”, “Officer” etc. suggest an established military hierarchy. “Mr” & “Sir” suggest business suits.

Last year, Wilson shared her process behind translating the first two lines of The Odyssey.

How much of Troy did he sack? ptoliethron is the lengthened form of polis, “city” (later, city-state). Sometimes =central part of city. But sacking just part of Troy isn’t really enough… Shd. the translator make it non-dumb if possible, or not worry about that?

There’s alliteration (polla/ plangthe … ptolietron epersen, notice the “p” sounds). What, if anything, should or can a translator do, when the sound of every word in her language is different from the words of the original? And, what to do about meter? Genre? Tone?

What’s the judgment, if any? Or narrative perspective? Do we feel OK about Odysseus being defined, instantly, as a city-sacker (ptoliporthos, one of his standard epithets)? Is the narrative voice invested in one side or another? It’s very hard to say. A judgment call.

And it goes on like that for more than a dozen tweets…for just two lines!

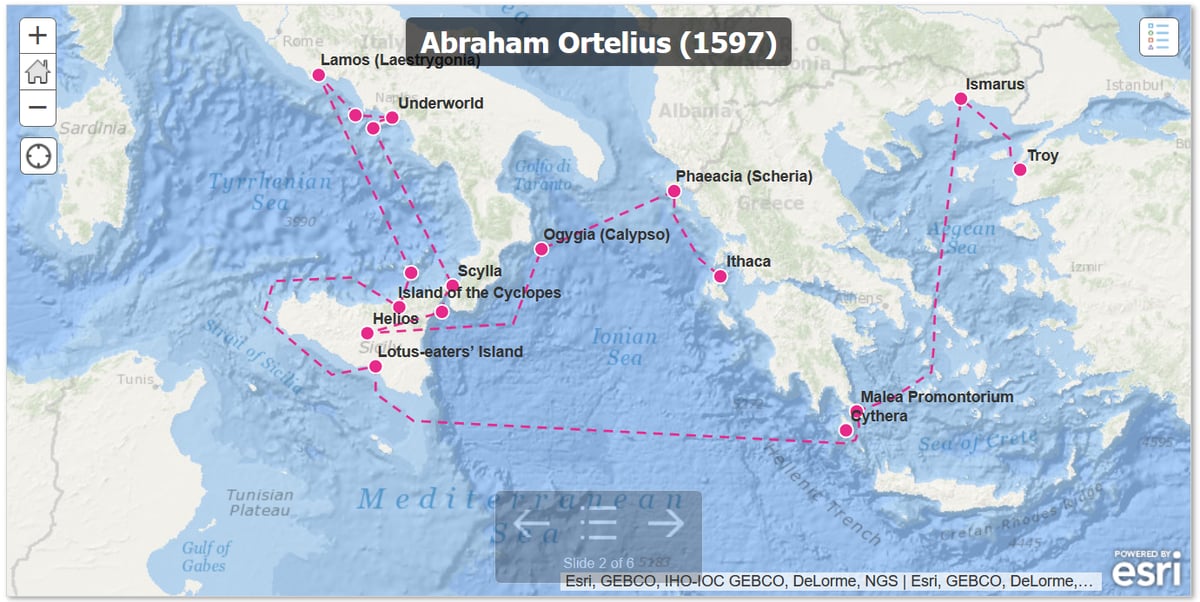

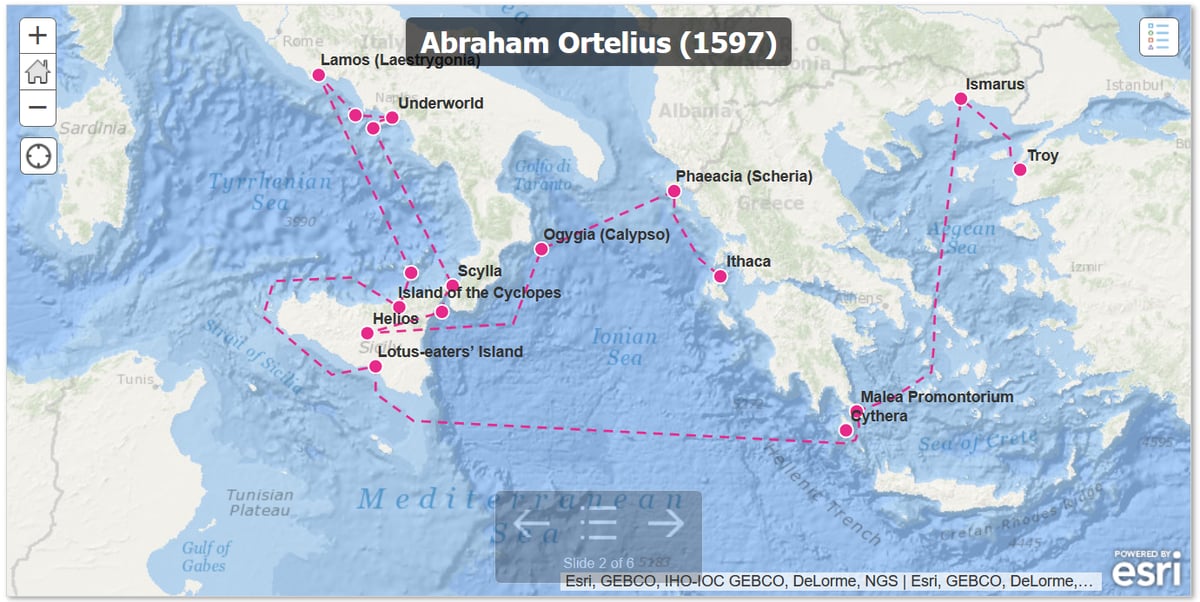

We’ve looked before at maps of Odysseus’s travels in The Odyssey (as Jason wrote in 2018, “that dude was LOST”). But it turns out — and maybe this shouldn’t be surprising — that it’s not easy to figure out exactly where Odysseus was in the Mediterranean Sea for all that time.

Scholars have pored over the text for clues for centuries, argued about their findings, and tried to interpret ambiguous language. We don’t even know for certain where Odysseus’s home island of Ithaca was.

Ithaca is one of a group of four islands, with smaller islands nearby, but it faces west while the others face east. (What does it mean for an island to face a direction?) It has forests and at least one mountain, and it is a good place for raising children. That isn’t much to go on.

Then there’s the whole question of what we gain from mapping The Odyssey in detail anyways. Some of it is plugging a gap in our imagination; we’ve gotten used to fantasy worlds supplying us with maps, and The Odyssey is a fantasy world that coexists with our own. But the level of detail is obsessive.

Attempts to map the Odyssey seem different from other attempts to locate the sites of famous myths and legends. Atlantis was the site of a wondrous civilization, Troy the landscape for an epic battle; finding them in the real world would mean discovering rich sources of evidence about past cultures. El Dorado’s location seems to have been coveted mainly for the lost city’s purported riches, Bimini for its rumored fountain of youth. But what do we gain by knowing where Helios kept his cows? Or which rocky, uninhabitable cave a kidnapping nymph called home?

Nevertheless, there’s a long history of scholars, artists, kings, and more attempting to write themselves into the myth of The Odyssey. The Aeneid, which simultaneously reimagines the founding of Rome as part of the story of the Iliad and Odyssey and elevates Virgil’s Latin poetry to the epic heights of Homer, is the most famous attempt to shore up a claim to legitimacy by appealing to the reality of the Odyssey’s ancient past.

But where exactly was Odysseus? Was he mostly in the Aegean and Italy, as Abraham Ortelius believed in 1597? Or was he scattered into the western Mediterranean, Spain, Corsica, North Africa, as Peter Struck thinks? We’ll probably never know. That dude was LOST.

I had been slowly making my way through Emily Wilson’s translation of The Odyssey, but on the advice of a Twitter pal, I backtracked and started reading it aloud to my kids. Which has been amazing…reading this story out loud really feels like we’re harkening back to the time of Homer.

One of the things we’re discussing as we go along are the repeated epithets…the descriptions of gods and people that are used over and over in the poem. Zeus is often not just Zeus — he is “the great Thunderlord Zeus” — and Dawn (the Greek goddess of the dawn) is almost never just Dawn, as Wilson explains in the introduction:

Dawn appears some twenty times in The Odyssey, and the poem repeats the same line, word for word, each time: emos d’erigeneia phane rhododaktulos eos: “But when early-born rosy-fingered Dawn appeared…” There is a vast array of such formulaic expressions in Homeric verse, which suggest that things have an eternal, infinitely repeatable presence. Different things will happen every day, but Dawn always appears, always with rosy fingers, always early.

Wilson combats this precise repetition, which can sound antiquated to modern ears, by varying the epithets according to the context:

The formulaic elements in Homer, especially the repeated epithets, pose a particular challenge. The epithets applied to Dawn, Athena, Hermes, Zeus, Penelope, Telemachus, Odysseus, and the suitors repeat over and over in the original. But in my version, I have chosen deliberately to interpret these epithets in several different ways, depending on the demands of the scene at hand. I do not want to deceive the unsuspecting reader about the nature of the original poem; rather, I hope to be truthful about my own text — its relationships with its readers and with the original. In an oral or semiliterate culture, repeated epithets give a listener an anchor in a quick-moving story. In a highly literate society such as our own, repetitions are likely to feel like moments to skip. They can be a mark of writerly laziness or unwillingness to acknowledge one’s own interpretative position, and can send a reader to sleep. I have used the opportunity offered by the repetitions to explore the multiple different connotations of each epithet.

The appearance of Dawn has already become a source of comic relief while we’re reading — “here she is again, with the roses!” — and I was curious to see Wilson’s differing interpretations, I gathered all the appearances of Dawn from the text:

The early Dawn was born; her fingers bloomed.

When newborn Dawn appeared with rosy fingers…

When rosy-fingered Dawn came bright and early…

Soon Dawn was born, her fingers bright with roses.

When Dawn appeared, her fingers bright with flowers…

When early Dawn appeared and touched the sky with blossom…

Then Dawn rose up from bed with Lord Tithonus, to bring the light to deathless gods and mortals.

When vernal Dawn first touched the sky with flowers…

But when the Dawn with dazzling braids brought day for the third time…

Then Dawn came from her lovely throne, and woke the girl.

Soon Dawn appeared and touched the sky with roses.

When bright-haired Dawn brought the third morning…

When early Dawn shone forth with rosy fingers…

But when the rosy hands of Dawn appeared…

Early the Dawn appeared, pink fingers blooming…

When early Dawn revealed her rose-red hands…

Then when rose-fingered Dawn came, bright and early…

On the third morning brought by braided Dawn…

Then the roses of Dawn’s fingers appeared again…

Dawn on her golden throne began to shine…

When Dawn came, born early, with her fingertips like petals…

The golden throne of Dawn was riding up the sky…

When rose-fingered Dawn appeared…

Then Dawn was born again; her fingers bloomed…

Then all at once Dawn on her golden throne lit up the sky…

…Dawn soon arrived upon her throne.

When newborn Dawn appeared with hands of flowers…

When early Dawn, the newborn child with rosy hands, appeared…

As she said this, the golden Dawn arrived.

…she roused the newborn Dawn from Ocean’s streams to bring the golden light to those on earth.

I think my favorite is probably “Soon Dawn was born, her fingers bright with roses” but I also appreciate the very first appearance in the text: “The early Dawn was born; her fingers bloomed”. Either way, what a great illustration of Wilson’s skill & the creative latitude involved in translation, along with a reminder for writers of the many different ways in which you can essentially say the same thing.

(The sunrise photo is from my Instagram.)

I can’t claim to have finished Emily Wilson’s translation of The Odyssey by Homer — epic poems are, well, epic — but I’m a huge fan of everything I’ve read, and especially Wilson’s Twitter feed, which is often devoted to explicating some small bit of Homeric text and comparing her approach to that of other translators.

Here, for example, she takes on the depiction of the Sirens. I’m going to pick and choose a few tweets, but you should read as much of the thread as you can.

This last observation prompted a haunting distillation by Lev Mirov of Odysseus’s journey and his encounter with the Sirens:

Back to Wilson, who translates the brutally short passage of the sirens this way:

She explains:

Translation is hard, but translation in public is harder and better. There’s a richness in the commentary, and also a reckoning with the accretion of meanings that have come down through past readings, that you don’t often get without diving into scholarly apparatus. It’s not just peeling back the plaster; it’s trying to understand the work that plaster did in holding the whole structure together. Just remarkable.

Update: Dan Chiasson wrote about Wilson’s use of Twitter for the New Yorker.

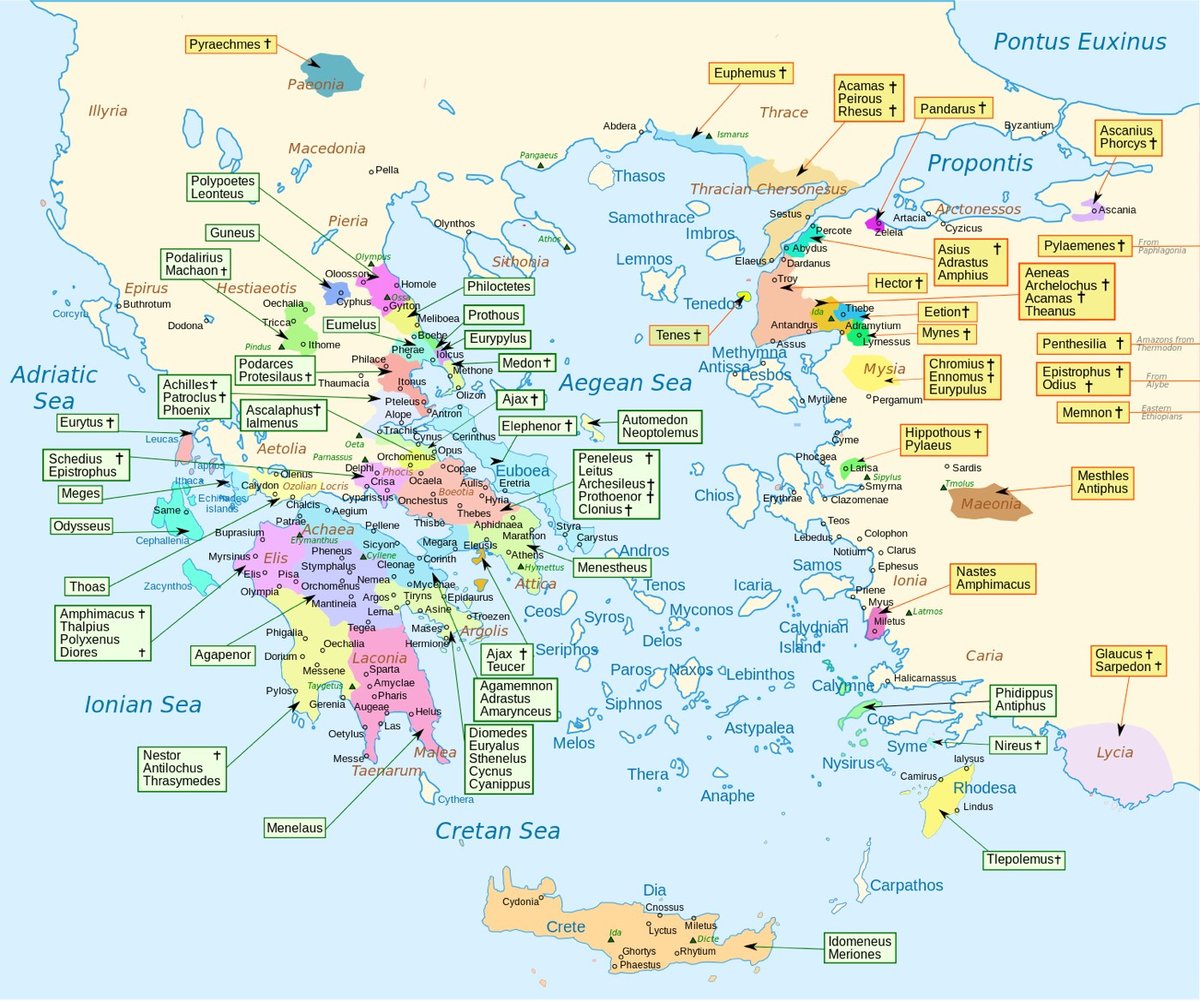

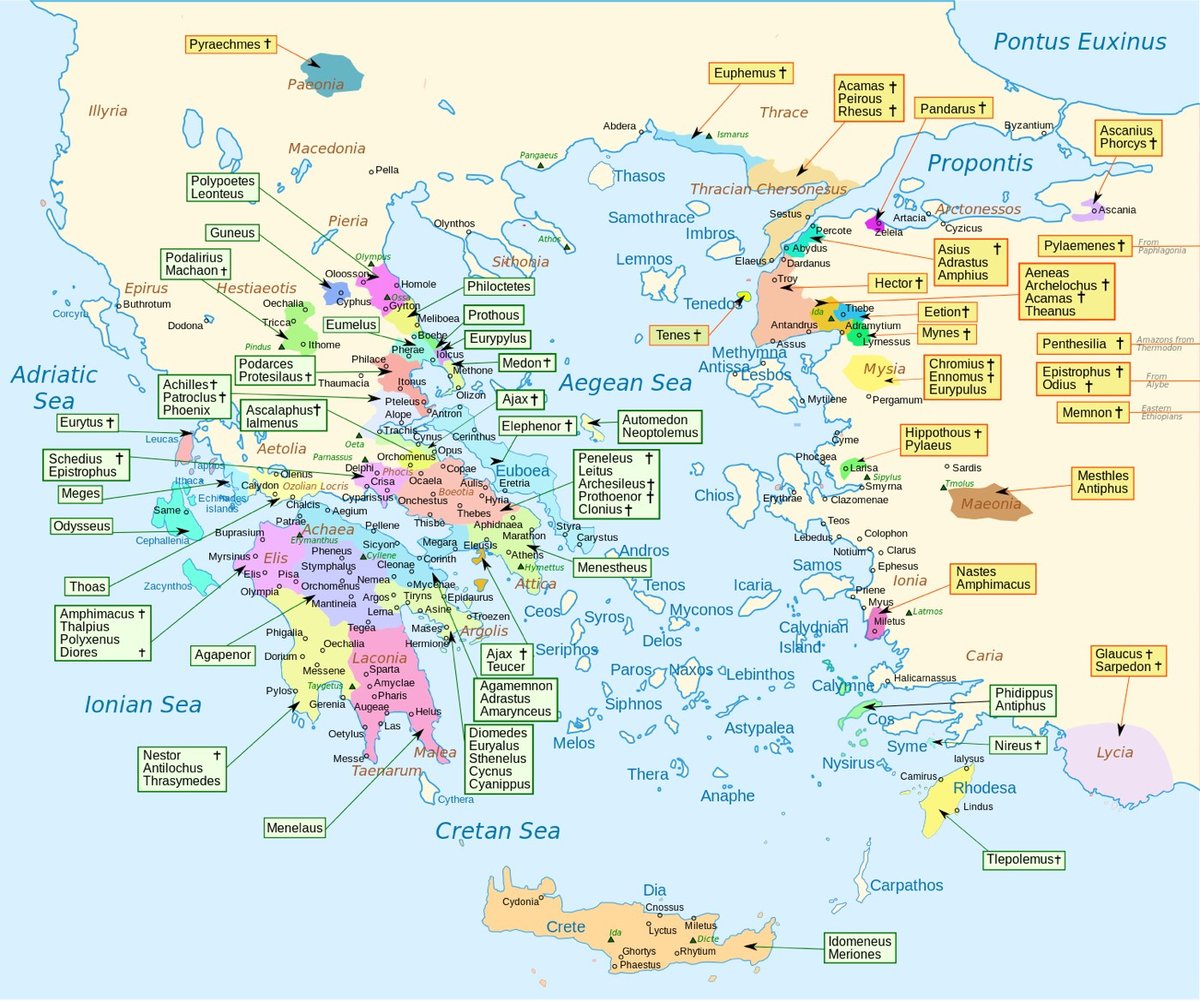

This is a map showing where all of the characters originated in Homer’s epic poem The Iliad. I know Greece is small by today’s standards, but it was surprising to me how geographically widespread the hometowns of the characters were. The Iliad is set sometime in the 11th or 12th century BC, about 400 years before Homer lived. I wonder if that level of mobility was accurate for the time or if Homer simply populated his poem with folks from all over Greece as a way of making listeners from many areas feel connected to the story — sort of the “hello, Cleveland!” of its time. (thx, adriana)

Update: I’ve gotten lots of feedback saying that not every character is represented in this map (particularly the women) and that some of the locations and hometowns are incorrect. Seems like Wikipedia might need to take a second look at it.

Update: The map was made using the Catalogue of Ships, a list of Achaean ships that sailed to Troy, and the Trojan Catalogue, a list of battle contingents that fought for Troy. That’s why it’s incomplete. An excerpt:

Now will I tell the captains of the ships and the ships in their order. Of the Boeotians Peneleos and Leïtus were captains, and Arcesilaus and Prothoënor and Clonius; these were they that dwelt in Hyria and rocky Aulis and Schoenus and Scolus and Eteonus with its many ridges, Thespeia, Graea, and spacious Mycalessus; and that dwelt about Harma and Eilesium and Erythrae; and that held Eleon and Hyle and Peteon, Ocalea and Medeon, the well-built citadel, Copae, Eutresis, and Thisbe, the haunt of doves; that dwelt in Coroneia and grassy Haliartus, and that held Plataea and dwelt in Glisas; that held lower Thebe, the well-built citadel, and holy Onchestus, the bright grove of Poseidon; and that held Arne, rich in vines, and Mideia and sacred Nisa and Anthedon on the seaboard.

(via @po8crg)

The structure of the social network among characters in Homer’s Odyssey indicates the story is at least partially based on actual events.

In analysing the Odyssey, they identified 342 unique characters and over 1700 relations between them.

Having constructed the social network, Miranda and co then examined its structure. “Odyssey’s social network is small world, highly clustered, slightly hierarchical and resilient to random attacks,” they say.

What’s interesting about this conclusion is that these same characteristics all crop up in social networks in the real world. Miranda and co say this is good evidence that the Odyssey is based, at least in part, on a real social network and so must be a mixture of myth and fact.

Stay Connected