kottke.org posts about timeless posts

vintage post from Sep 2014

In this video entitled Rush Hour, cars, pedestrians, and cyclists have been edited together to produce dozens of heart-stopping near misses.

Reminds me of the world’s craziest intersection, traffic organized by color, intersections in the age of driverless cars, and the dangerous dance of NYC intersections. (via colossal)

vintage post from Oct 2016

In his film Best of Luck With the Wall, director Josh Begley takes us on a journey across the entire US/Mexico border. It’s a simple premise — a continuous display of 200,000 satellite images of the border from the Pacific Ocean to the Gulf of Mexico — but one that delivers a powerful feeling of how large the world is and how meaningless borders are from a certain perspective.

The project started from a really simple place. It was about looking. It was about the pure desire to understand the visual landscape that we are talking about when we are talking about the southern border of the United States. What does the southern border of the United States actually look like? And in that sense it was a very simple gesture to try to see the border in aggregate. If you were to compile all 2000 miles and try to see it in a short space — what would that look like? In another sense it grew out of the discourses as you suggested. The way migration is talked about in our contemporary moment and in particular the way migration is talked about in terms of the southern border of the U.S. So part of this piece is a response to the way migrants and borders are talked about in our politics. And it’s also just a way of looking at landscape as a way to think about some of those things.

The online version of the film is 6 minutes long, but Begley states that longer versions might make their way into galleries and such.

vintage post from Jun 2012

Artist Jason Freeny is making these neat anatomical sculptures of Lego people.

You can see more of his work in progress on his Facebook page. Reminds me of Michael Paulus’ work. (via colossal)

vintage post from May 2015

Jellyfish Lake in Palau is home to approximately 13 million jellyfish. Their mild stings mean you can snorkel in their midst and capture beautifully surreal scenes like this:

If I had a bucket list, I think a swim in Jellyfish Lake w/ classical accompaniment might be on it. (via colossal)

vintage post from Mar 2014

I read this piece by Jessica Winter a few months ago and it’s come in handy a few times so I thought I’d share. If you want something from someone, adopting the pose of the Kindly Brontosaurus might go a lot further than throwing a fit.

A practitioner, nay, an artist, of the Kindly Brontosaurus method would approach the gate agent as follows. You state your name and request. You make a clear and concise case. And then, after the gate agent informs you that your chances of making it onto this flight are on par with the possibility that a dinosaur will spontaneously reanimate and teach himself to fly an airplane, you nod empathically, say something like “Well, I’m sure we can find a way to work this out,” and step just to the side of the agent’s kiosk.

Here is where the Kindly Brontosaurus rears amiably into the frame. You must stand quietly and lean forward slightly, hands loosely clasped in a faintly prayerful arrangement. You will be in the gate agent’s peripheral vision-close enough that he can’t escape your presence, not so close that you’re crowding him-but you must keep your eyes fixed placidly on the agent’s face at all times. Assemble your features in an understanding, even beatific expression. Do not speak unless asked a question. Whenever the gate agent says anything, whether to you or other would-be passengers, you must nod empathically.

Continue as above until the gate agent gives you your seat number. The Kindly Brontosaurus always gets a seat number.

Note: Illustration by Chris Piascik.

vintage post from Apr 2016

Koyannistocksi is a shot-by-shot remake of the trailer for Godfrey Reggio’s Koyaanisqatsi using only stock footage.

A testament to Reggio’s influence on contemporary motion photography, and the appropriation of his aesthetic by others for commercial means.

(via @waxpancake)

vintage post from Jun 2012

Speaking of what fast looks like, here’s a pair of synced videos that show just how fast F1 cars are. On the left are drivers participating in a track day, that is, normal folks who want to drive their cars fast on a real race course. A couple of them look like actual GT cars and are moving pretty quick. On the right, you’ve got F1 cars on the same track. It’s not even close:

Here’s an overlaid version and you can also see how much faster F1 cars are than just 25 years ago…the 2011 F1 car beats the 1986 F1 car by an amazing 22 seconds over a total time of a minute and a half. (via @coreyh)

Update: In a speed test, an F1 car starts 40 seconds after a Mercedes sports car and 25 seconds after a V8 Supercar (essentially an Australian NASCAR) and still catches them by the end of the first lap.

vintage post from Apr 2016

If you can stop gawping at Alaska’s gorgeous scenery long enough, you can witness drone footage of a whole lot of salmon migrating upstream from Lake Iliamna1 to spawn. (via digg)

vintage post from Apr 2012

Caine is nine years old, lives in LA, and built his own arcade out of cardboard boxes in the back of his father’s auto parts store.

You’ve go to watch until at least 3:10 when he explains how to check the validity of the “Fun Pass” using the calculators located on the front of each game. So so so good!

vintage post from Mar 2015

From Charlie Brooker’s Weekly Wipe, here’s how every single news report on the economy plays out:

Dennis and Pamela People are affected by numbers, and since they have a child, you’ll empathize with what they say while I nod in their direction.

“Well, it’s been hard because of the numbers.”

“Yeah, it has been hard, mainly because of the numbers.”

Brooker, you may remember, is the creator of Black Mirror.

vintage post from Dec 2012

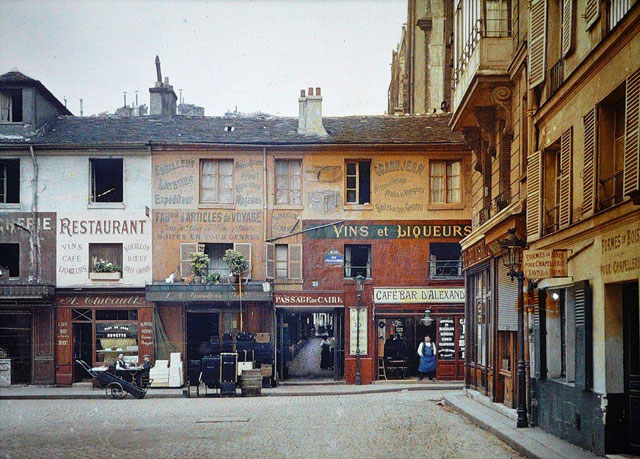

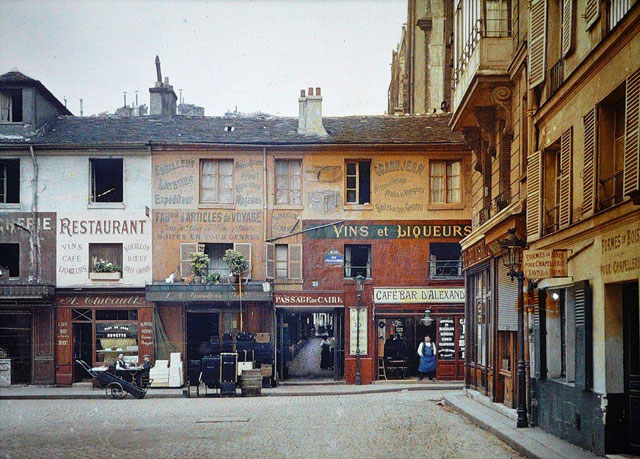

Albert Kahn sent photographers all over the world in the early 1900s and amassed over 72,000 color photos in the process. Here are a few shots of his from Paris on the eve of World War I.

That photo is of the entrance to the Passage du Caire at the corner of Rue d’Alexandrie and Rue Sainte-Foy in the 2nd arrondissement. Here’s what it looks like today:

vintage post from May 2013

From a passage of Kurt Vonnegut’s Bluebeard, the three types of specialists needed for the success of any revolution.

Slazinger claims to have learned from history that most people cannot open their minds to new ideas unless a mind-opening team with a peculiar membership goes to work on them. Otherwise, life will go on exactly as before, no matter how painful, unrealistic, unjust, ludicrous, or downright dumb that life may be.

The team must consist of three sorts of specialists, he says. Otherwise the revolution, whether in politics or the arts or the sciences or whatever, is sure to fail.

The rarest of these specialists, he says, is an authentic genius — a person capable of having seemingly good ideas not in general circulation. “A genius working alone,” he says, “is invariably ignored as a lunatic.”

The second sort of specialist is a lot easier to find: a highly intelligent citizen in good standing in his or her community, who understands and admires the fresh ideas of the genius, and who testifies that the genius is far from mad. “A person like this working alone,” says Slazinger, “can only yearn loud for changes, but fail to say what their shapes should be.”

The third sort of specialist is a person who can explain everything, no matter how complicated, to the satisfaction of most people, no matter how stupid or pigheaded they may be. “He will say almost anything in order to be interesting and exciting,” says Slazinger. “Working alone, depending solely on his own shallow ideas, he would be regarded as being as full of shit as a Christmas turkey.”

Slazinger, high as a kite, says that every successful revolution, including Abstract Expressionism, the one I took part in, had that cast of characters at the top — Pollock being the genius in our case, Lenin being the one in Russia’s, Christ being the one in Christianity’s.

He says that if you can’t get a cast like that together, you can forget changing anything in a great big way.

(via @moleitau)

vintage post from Feb 2012

This is a 1930 short film from avant-garde filmmaker Ralph Steiner that shows dozens of gears and other machinery at work.

(thx, matthew)

vintage post from Oct 2015

Drawing upon the work of colleagues, historian Michael Todd Landis proposes new language for talking about slavery and the Civil War. In addition to favoring “labor camps” over the more romantic “plantations”, he suggests retiring the concept of the Union vs the Confederacy.

Specifically, let us drop the word “Union” when describing the United States side of the conflagration, as in “Union troops” versus “Confederate troops.” Instead of “Union,” we should say “United States.” By employing “Union” instead of “United States,” we are indirectly supporting the Confederate view of secession wherein the nation of the United States collapsed, having been built on a “sandy foundation” (according to rebel Vice President Alexander Stephens). In reality, however, the United States never ceased to exist. The Constitution continued to operate normally; elections were held; Congress, the presidency, and the courts functioned; diplomacy was conducted; taxes were collected; crimes were punished; etc. Yes, there was a massive, murderous rebellion in at least a dozen states, but that did not mean that the United States disappeared.

vintage post from Apr 2013

Filmed at 780 fps with a Phantom Flex from the back of a moving SUV, James Nares’ Street depicts people walking New York streets in super slow motion.

The film runs 60 minutes (depicting about three minutes of real time footage), Sonic Youth’s Thurston Moore did the soundtrack, and it’s on display at The Met until the end of May.

Update: Here’s another short clip of the full film from the National Gallery of Art.

vintage post from Aug 2016

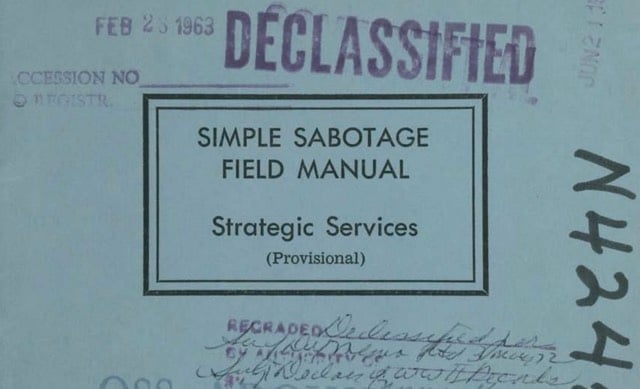

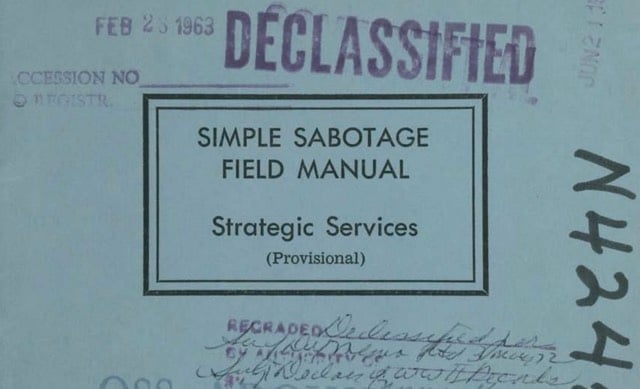

In 1944, the OSS (the precursor to the CIA) produced a document called the Simple Sabotage Field Manual (PDF). It was designed to be used by agents in the field to hinder our WWII adversaries. The CIA recently highlighted five tips from the manual as timelessly relevant:

1. Managers and Supervisors: To lower morale and production, be pleasant to inefficient workers; give them undeserved promotions. Discriminate against efficient workers; complain unjustly about their work.

2. Employees: Work slowly. Think of ways to increase the number of movements needed to do your job: use a light hammer instead of a heavy one; try to make a small wrench do instead of a big one.

3. Organizations and Conferences: When possible, refer all matters to committees, for “further study and consideration.” Attempt to make the committees as large and bureaucratic as possible. Hold conferences when there is more critical work to be done.

4. Telephone: At office, hotel and local telephone switchboards, delay putting calls through, give out wrong numbers, cut people off “accidentally,” or forget to disconnect them so that the line cannot be used again.

5. Transportation: Make train travel as inconvenient as possible for enemy personnel. Issue two tickets for the same seat on a train in order to set up an “interesting” argument.

Ha, some of these things are practically best practices in American business, not against enemies but against their employees, customers, and themselves. You can also find the manual in book or ebook format. (via @craigmod)

vintage post from Dec 2012

Cy Kuckenbaker compressed five hours of landing planes into 30 seconds of video. I love this. A great example of time merge media. (via colossal, which has been killing it lately)

vintage post from Mar 2012

Speaking of the Road Runner and Wile E. Coyote, animator Chuck Jones and his team were said to follow these simple rules when creating the cartoons:

- The Road Runner cannot harm the Coyote except by going “meep, meep.”

- No outside force can harm the Coyote — only his own ineptitude or the failure of Acme products. Trains and trucks were the exception from time to time.

- The Coyote could stop anytime — if he were not a fanatic.

- No dialogue ever, except “meep, meep” and yowling in pain.

- The Road Runner must stay on the road — for no other reason than that he’s a roadrunner.

- All action must be confined to the natural environment of the two characters — the southwest American desert.

- All tools, weapons, or mechanical conveniences must be obtained from the Acme Corporation.

- Whenever possible, make gravity the Coyote’s greatest enemy.

- The Coyote is always more humiliated than harmed by his failures.

- The audience’s sympathy must remain with the Coyote.

- The Coyote is not allowed to catch or eat the Road Runner.

The rules are made only slightly less interesting by their fiction; according to Wikipedia, long-time Jones collaborator Michael Maltese said he’d never heard of the rules.

vintage post from Oct 2015

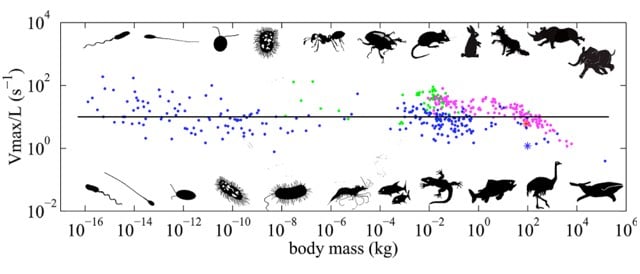

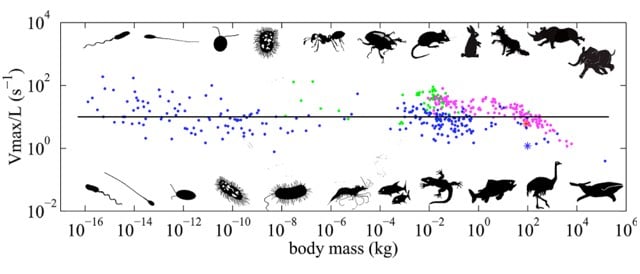

A recent paper found that the time it takes for an animal to move the length of its own body is largely independent of mass. This appears to hold from tiny bacteria on up to whales — that’s more than 20 orders of magnitude of mass. The paper’s argument as to why this happens relies on scaling laws. Alex Klotz explains.

A well-known example is the Square-Cube Law, dating back to Galileo and described quite well in the Haldane essay, On Being the Right Size. The Square-Cube Law essentially states that if something, be it a chair or a person or whatever, were made twice as tall, twice as wide, and twice as deep, its volume and mass would increase by a factor of eight, but its ability to support that mass, its cross sectional area, would only increase by a factor of four. This means as things get bigger, their own weight becomes more significant compared to their strength (ants can carry 50 times their own weight, squirrels can run up trees, and humans can do pullups).

Another example is terminal velocity: the drag force depends on the cross-sectional area, which (assuming a spherical cow) goes as the square of radius (or the two-thirds power of mass), while the weight depends on the volume, proportional to the cube of radius or the first power of mass. As Haldane graphically puts it

“You can drop a mouse down a thousand-yard mine shaft; and, on arriving at the bottom, it gets a slight shock and walks away, provided that the ground is fairly soft. A rat is killed, a man is broken, a horse splashes.”

Scaling laws also come into play in determining the limits of the size of animals: The Biology of B-Movie Monsters.

When the Incredible Shrinking Man stops shrinking, he is about an inch tall, down by a factor of about 70 in linear dimensions. Thus, the surface area of his body, through which he loses heat, has decreased by a factor of 70 x 70 or about 5,000 times, but the mass of his body, which generates the heat, has decreased by 70 x 70 x 70 or 350,000 times. He’s clearly going to have a hard time maintaining his body temperature (even though his clothes are now conveniently shrinking with him) unless his metabolic rate increases drastically.

Luckily, his lung area has only decreased by 5,000-fold, so he can get the relatively larger supply of oxygen he needs, but he’s going to have to supply his body with much more fuel; like a shrew, he’ll probably have to eat his own weight daily just to stay alive. He’ll also have to give up sleeping and eat 24 hours a day or risk starving before he wakes up in the morning (unless he can learn the trick used by hummingbirds of lowering their body temperatures while they sleep).

vintage post from Sep 2018

Frustrated that the US Treasury Department is walking back plans to replace Andrew Jackson on the front of the $20 bill with Harriet Tubman, Dano Wall created a 3D-printed stamp that can be used to transform Jacksons into Tubmans on the twenties in your pocketbook.

Here’s a video of the stamp in action. Wall told The Awesome Foundation a little bit about the genesis of the project:

I was inspired by the news that Harriet Tubman would replace Andrew Jackson on the $20 bill, and subsequently saddened by the news that the Trump administration was walking back that plan. So I created a stamp to convert Jacksons into Tubmans myself. I have been stamping $20 bills and entering them into circulation for the last year, and gifting stamps to friends to do the same.

If you have access to a 3D printer (perhaps at your local library or you can also use a online 3D printing service), you can download the print files at Thingiverse and make your own stamp for use at home.

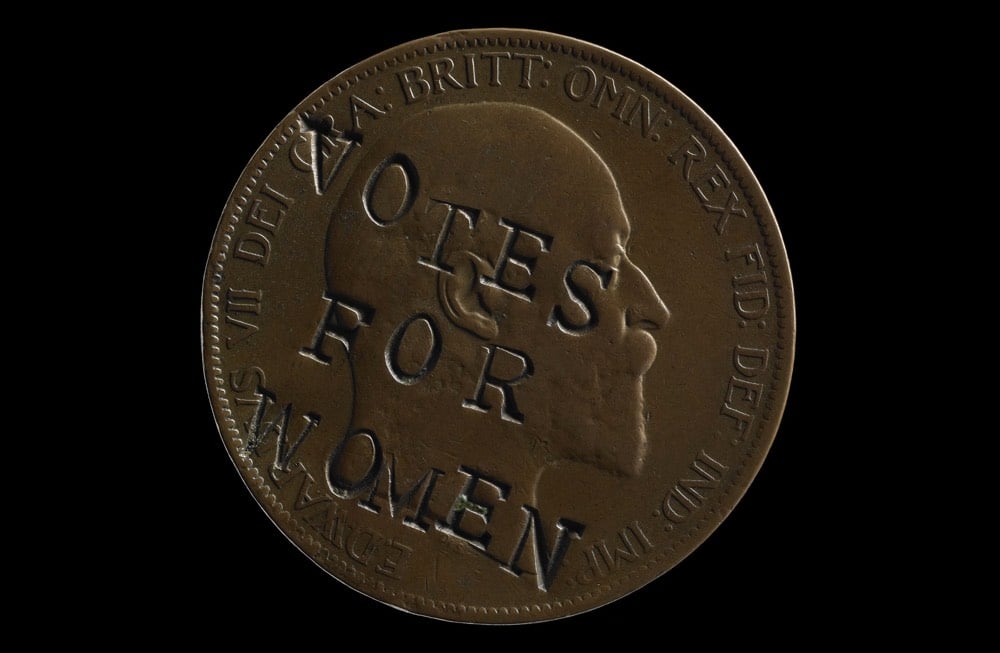

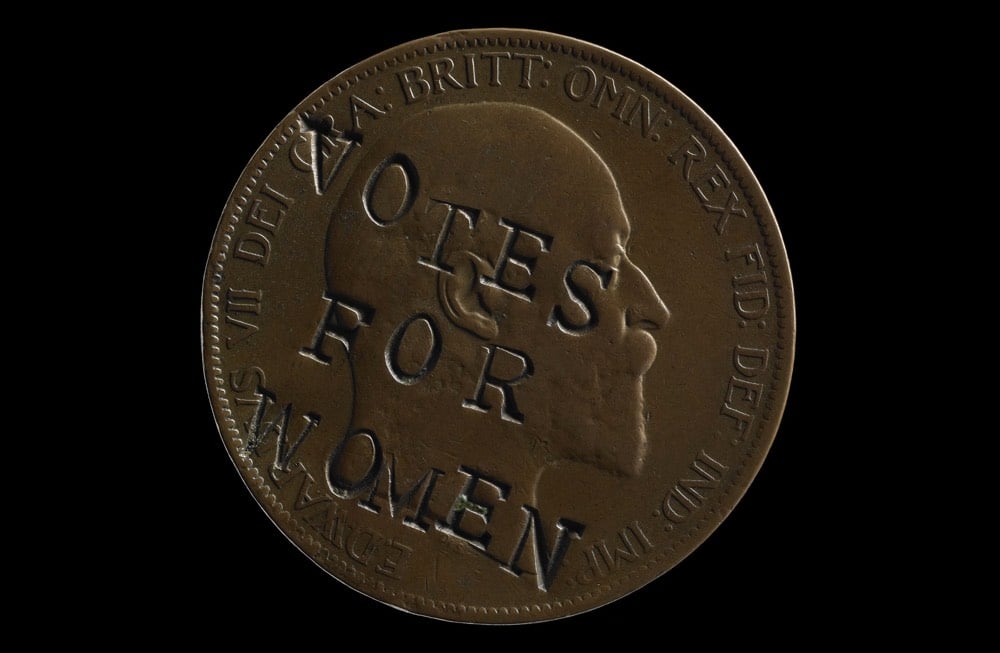

Wall also posted a link to some neat prior art: suffragettes in Britain modifying coins with a “VOTES FOR WOMEN” slogan in the early 20th century.

Update: Several men on Twitter are helpfully pointing out that, in their inexpert legal opinion, defacing bills in this way is illegal. Here’s what the law says (emphasis mine):

Defacement of currency is a violation of Title 18, Section 333 of the United States Code. Under this provision, currency defacement is generally defined as follows: Whoever mutilates, cuts, disfigures, perforates, unites or cements together, or does any other thing to any bank bill, draft, note, or other evidence of debt issued by any national banking association, Federal Reserve Bank, or Federal Reserve System, with intent to render such item(s) unfit to be reissued, shall be fined under this title or imprisoned not more than six months, or both.

The “with intent” bit is important, I think. The FAQ for a similar project has a good summary of the issues involved.

But we are putting political messages on the bills, not commercial advertisements. Because we all want these bills to stay in circulation and we’re stamping to send a message about an issue that’s important to us, it’s legal!

I’m not a lawyer, but as long as your intent isn’t to render these bills “unfit to be reissued”, you’re in the clear. Besides, if civil disobedience doesn’t stray into the gray areas of the law, is it really disobedience? (via @patrick_reames)

Update: Adafruit did an extensive investigation into the legality of this project. Their conclusion? “The production of the instructional video and the stamping of currency are both well within the law.”

vintage post from May 2016

A new video from Kurzgesagt explores the limits of human exploration in the Universe. How far can we venture? Are there limits? Turns out the answer is very much “yes”…with the important caveat “using our current understanding of physics”, which may someday provide a loophole (or wormhole, if you will). Chances are, humans will only be able to explore 0.00000000001% of the observable Universe.

This video is particularly interesting and packed with information, even by Kurzgesagt’s standards. The explanation of the Big Bang, inflation, dark matter, and expansion is concise and informative…the idea that the Universe is slowly erasing its own memory is fascinating.

vintage post from Nov 2008

Brian Eno believes that singing is the key to a good life.

Singing aloud leaves you with a sense of levity and contentedness. And then there are what I would call “civilizational benefits.” When you sing with a group of people, you learn how to subsume yourself into a group consciousness because a capella singing is all about the immersion of the self into the community. That’s one of the great feelings — to stop being me for a little while and to become us. That way lies empathy, the great social virtue.

(via subtraction)

vintage post from Apr 2013

Leigh Singer gathered more than 50 clips from movies that break the fourth wall (where the characters acknowledge they’re in a movie).

Sadly my favorite broken fourth wall moment didn’t make the list: Billy Ray Valentine in Trading Places getting a commodities lesson from the Dukes. (via zupped)

Update: Ah, and all is right with the universe again as Trading Places makes it into Singer’s second compilation of fourth wall breaks.

vintage post from Feb 2012

The Euthanasia Coaster is designed to thrill the hell out of its passengers just before it kills them.

Each inversion would have a smaller diameter than the one before in order to inflict 10 g to passengers while the train loses speed. After a sharp right-hand turn the train would enter a straight, where unloading of bodies and loading of passengers could take place.

The Euthanasia Coaster would kill its passengers through prolonged cerebral hypoxia, or insufficient supply of oxygen to the brain. The ride’s seven inversions would inflict 10 g on its passengers for 60 seconds — causing g-force related symptoms starting with gray out through tunnel vision to black out and eventually g-LOC, g-force induced loss of consciousness. Depending on the tolerance of an individual passenger to g-forces, the first or second inversion would cause cerebral anoxia, rendering the passengers brain dead. Subsequent inversions would serve as insurance against unintentional survival of passengers.

More information on the project is here.

vintage post from Sep 2014

After the Civil War, the economic recovery of the southern United States hinged on trade with the North and moving goods westward via the railroad. But there was a problem. Tracks in the South had been built with a gauge (or track width) of 5 feet but the majority of tracks in the North had a 4-foot 9-inch gauge (more or less). So after much planning, over a concentrated two-day period in the summer of 1886, the width of thousands of miles of railroad track (and the wheels on thousands of rail cars) in the South was reduced by three inches.

Only one rail would be moved in on the day of the change, so inside spikes were hammered into place at the new gauge width well in advance of the change, leaving only the need for a few blows of the sledgehammer once the rail was placed. As May 31 drew near, some spikes were pulled from the rail that was to be moved in order to reduce as much as possible the time required to release the rail from its old position.

Rolling stock, too, was being prepared for rapid conversion. Contemporary accounts indicate that dish shaped wheels were provided on new locomotives so that on the day of the change, reversing the position of the wheel on the axle would make the locomotive conform to the new gauge. On some equipment, axles were machined to the new gauge and a special ring positioned inside the wheel to hold it to the 5-foot width until the day of the gauge change. Then the wheel was pulled, the ring removed, and the wheel replaced.

To shorten the axles of rolling stock and motive power that could not be prepared in advance, lathes and crews were stationed at various points throughout the South to accomplish the work concurrently with the change in track gauge.

And you thought deploying software was difficult.

Update: In their book Information Rules, Carl Shapiro and Hal Varian point out that sometimes having different standards from the norm is a good thing.

As things turned out, having different gauges was advantageous to the South, since the North could not easily use railroad to move its troops to battle in southern territory during the Civil War. Noting this example, the Finns were careful to ensure that their railroads used a gauge different from the Russian railroads! The rest of Europe adopted a standard gauge, which made things easy for Hitler during World War II: a significant fraction of German troop movements in Europe were accomplished by rail.

They also describe the efforts that the South went through to support the stronger standard of the North without switching over:

In 1862, Congress specified the standard gauge for the transcontinental railroads. By this date, the southern states had seceded, leaving no one to push for the 5-foot gauge. After the war, the southern railroads found themselves increasingly in the minority. For the next twenty years, they relied on various imperfect means of interconnection with the North and West: cars with a sliding wheel base, hoists to lift cars from one wheel base to another, and, most commonly, a third rail.

At home, I have a drawer full of sliding wheel bases and third rails in the form of Euro-to-US & Asia-to-US power adapters.

vintage post from May 2012

Using a video game metaphor, John Scalzi explains straight white male privilege for those straight white males who get hung up on the word “privilege”.

Dudes. Imagine life here in the US — or indeed, pretty much anywhere in the Western world — is a massive role playing game, like World of Warcraft except appallingly mundane, where most quests involve the acquisition of money, cell phones and donuts, although not always at the same time. Let’s call it The Real World. You have installed The Real World on your computer and are about to start playing, but first you go to the settings tab to bind your keys, fiddle with your defaults, and choose the difficulty setting for the game. Got it?

Okay: In the role playing game known as The Real World, “Straight White Male” is the lowest difficulty setting there is.

You can lose playing on the lowest difficulty setting. The lowest difficulty setting is still the easiest setting to win on. The player who plays on the “Gay Minority Female” setting? Hardcore.

vintage post from Feb 2013

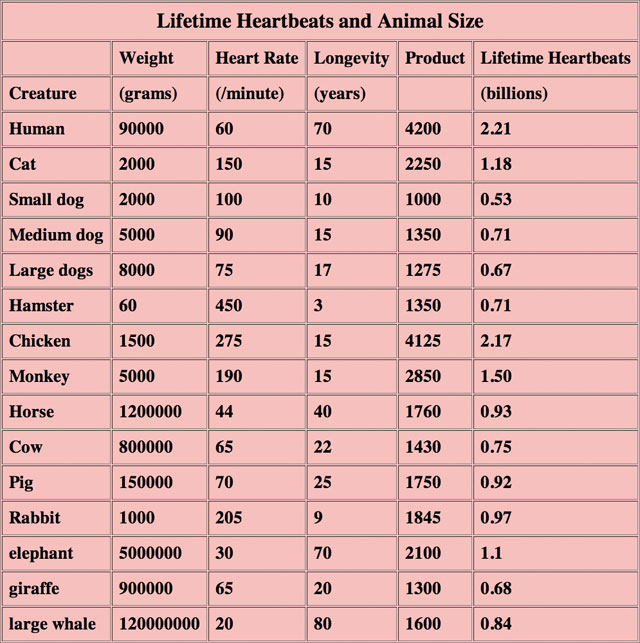

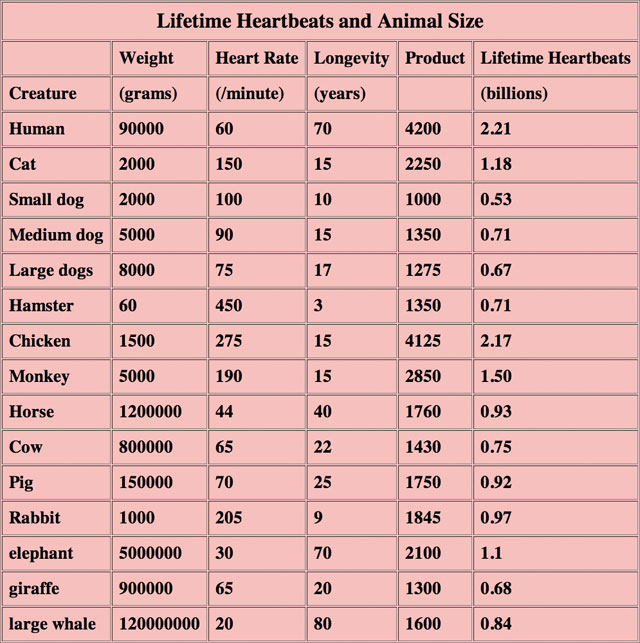

There’s an assumption that because of the relationship between metabolic rates, volume, and surface area, animals get an average of one billion heartbeats out of their bodies before they expire. Turns out there’s some truth to it.

As animals get bigger, from tiny shrew to huge blue whale, pulse rates slow down and life spans stretch out longer, conspiring so that the number of heartbeats during an average stay on Earth tends to be roughly the same, around a billion.

Mysteriously, these and a large variety of other phenomena change with body size according to a precise mathematical principle called “quarter-power scaling”.

It might seem that because a cat is a hundred times more massive than a mouse, its metabolic rate, the intensity with which it burns energy, would be a hundred times greater. After all, the cat has a hundred times more cells to feed.

But if this were so, the animal would quickly be consumed by a fit of spontaneous feline combustion, or at least a very bad fever. The reason: the surface area a creature uses to dissipate the heat of the metabolic fires does not grow as fast as its body mass.

To see this, consider a mouse as an approximation of a small sphere. As the sphere grows larger, to cat size, the surface area increases along two dimensions but the volume increases along three dimensions. The size of the biological radiator cannot possibly keep up with the size of the metabolic engine.

Humans and chickens are both outliers in this respect…they both live more than twice as long as their heart rates would indicate. Small dogs live about half as long.

vintage post from Aug 2014

Watch Peanuts creator Charles Schulz draw Charlie Brown. It only takes him around 35 seconds.

(via @fchimero)

vintage post from Sep 2016

Johanna Nordblad is a free diver who specializes in cold water dives. After being injured in a biking accident, her recovery involved ice water baths and she developed an interest in cold water. Ian Derry filmed Nordblad doing a dive for this gorgeous short video.

There is no place for fear, no place for panic, no place for mistakes. Under the ice, you need total control of the place, the time, and to trust yourself completely.

(via @daveg)

vintage post from Jan 2013

Writing for The Awl, Jeb Boniakowski shares his vision for a massive McDonald’s complex in Times Square that serves food from McDonald’s restaurants from around the world, offers discontinued food items (McLean Deluxe anyone?), and contains a food lab not unlike David Chang’s Momofuku test kitchen.

The central attraction of the ground floor level is a huge mega-menu that lists every item from every McDonald’s in the world, because this McDonald’s serves ALL of them. There would probably have to be touch screen gadgets to help you navigate the menu. There would have to be whole screens just dedicated to the soda possibilities. A concierge would offer suggestions. Celebrities on the iPad menus would have their own “meals” combining favorites from home (“Manu Ginobili says ‘Try the medialunas!’”) with different stuff for a unique combination ONLY available at McWorld. You could get the India-specific Chicken Mexican Wrap (“A traditional Mexican soft flat bread that envelops crispy golden brown chicken encrusted with a Mexican Cajun coating, and a salad mix of iceberg lettuce, carrot, red cabbage and celery, served with eggless mayonnaise, tangy Mexican Salsa sauce and cheddar cheese.” Wherever possible, the menu items’ descriptions should reflect local English style). Maybe a bowl of Malaysian McDonald’s Chicken Porridge or The McArabia Grilled Kofta, available in Pakistan and parts of the Middle East. You should watch this McArabia ad for the Middle Eastern-flavored remix of the “I’m Lovin’ It” song if for nothing else.

And I loved his take on fast food as molecular gastronomy:

How much difference really is there between McDonald’s super-processed food and molecular gastronomy? I used to know this guy who was a great chef, like his restaurant was in the Relais & Châteaux association and everything, and he’d always talk about how there were intense flavors in McDonald’s food that he didn’t know how to make. I’ve often thought that a lot of what makes crazy restaurant food taste crazy is the solemn appreciation you lend to it. If you put a Cheeto on a big white plate in a formal restaurant and serve it with chopsticks and say something like “It is a cornmeal quenelle, extruded at a high speed, and so the extrusion heats the cornmeal ‘polenta’ and flash-cooks it, trapping air and giving it a crispy texture with a striking lightness. It is then dusted with an ‘umami powder’ glutamate and evaporated-dairy-solids blend.” People would go just nuts for that. I mean even a Coca-Cola is a pretty crazy taste.

I love both mass-produced processed foods and the cooking of chefs like Grant Achatz & Ferran Adrià. Why is the former so maligned while the latter gets accolades when they’re the same thing? (And simultaneously not the same thing at all, but you get my gist.) Cheetos are amazing. Oscar Meyer bologna is amazing. Hot Potato Cold Potato is amazing. Quarter Pounders with Cheese are amazing. Adrià’s olives are amazing. Coca-Cola is amazing. (Warhol: ” A Coke is a Coke and no amount of money can get you a better Coke than the one the bum on the corner is drinking.”) WD50’s Everything Bagel is amazing. Cheerios are amazing. All have unique flavors that don’t exist in nature — you’ve got to take food apart and put it back together in a different way to find those new tastes.

Some of these fancy chefs even have an appreciation of mass produced processed foods. Eric Ripert of the 4-star Le Berdardin visited McDonald’s and Burger King to research a new burger for one of his restaurants. (Ripert also uses processed Swiss cheese as a baseline flavor at Le Bernardin.) David Chang loves instant ramen and named his restaurants after its inventor. Ferran Adrià had his own flavor of Lay’s potato chips in Spain. Thomas Keller loves In-N-Out burgers. Grant Achatz eats Little Caesars pizza.

Newer posts

Older posts

Socials & More