50 Years of Text Games by Aaron Reed is a favorite newsletter of mine. (It’s a hard newsletter to read in your email right away, but a rewarding one to pile up and save.) It specializes in in-depth explorations, typically at a single game per newsletter, but also takes a wider view to try to understand why this game at that moment was particularly significant or representative.

Here’s an example of a great newsletter about a game I do not know well: Graham Nelson’s Curses, from 1993. Curses, Reed, argues, emerges at an unlikely moment (surrounded by emerging CD-ROM games and exploding console popularity) to bring about an equally unlikely renaissance of interactive fiction.

Curses is scavenger hunt meets Dante’s Inferno, “an allegorical rite of passage,” adventure game by way of historical footnote. It certainly owes a great debt to Infocom, recreating the company’s signature style even while literally resurrecting its technical bones…

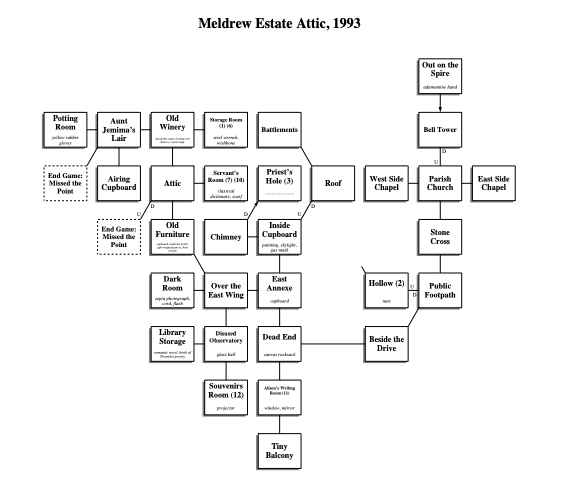

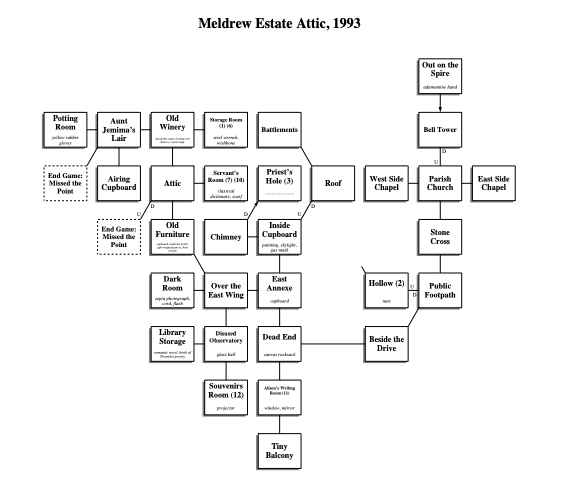

But Nelson also took much inspiration from history and classics. When asked once about his favorite games and authors, he gave much more space to the latter, listing “Auden, Eliot, Donne, Browning, Elizabeth Bishop… For plays, Tom Stoppard, Christopher Hampton, David Hare.” Curses is steeped in antiquities, from the abandoned odds and ends squirreled away in the Meldrew attics—an old wireless radio, for instance, which seems to do nothing when turned on until you realize it just takes a few turns to warm up—to its detailed time travel excursions to lovingly researched long-ago eras. It’s a game very much about odd corners and margins: interstitial places…

Nelson’s game would take over the IF newsgroups as players who thought they’d seen the last of the great text adventures discovered a worthy modern successor. “Congratulations,” wrote one poster: “Its almost like having Infocom back.” It helped that the game had so many nooks and crannies and puzzles, endless puzzles, that at least some of them were bound to be stumpers for any given player. Hint requests and discussion of the game proliferated, and dominated the newsgroups through the rest of 1993 and 1994: so much so there was a half-hearted proposal to split it all off into a dedicated new group, rec.games.curses, just so there’d be enough oxygen to talk about anything else.

The other big thing Nelson did with Curses is build a compiler for the Infocom virtual machine so that players and designers could create their own text adventures. Kind of like Dante importing the classic epic into the vernacular. Everybody could now do it themselves.

That juncture — a compelling world, an obsessed and supportive community, and (there’s no better way to put this) the means of creative production — have proved over and over again to be the secret formula for building something beautiful and new in art.

It’s a throwaway line in a longer talk and we probably shouldn’t make too much of it, but I will anyway.

In five years time Facebook “will be definitely mobile, it will be probably all video,” said Nicola Mendelsohn, who heads up Facebook’s operations in Europe, the Middle East and Africa, at a conference in London this morning. Mark Zuckerberg, Facebook’s CEO, has already noted that video will be more and more important for the platform. But Mendelsohn went further, suggesting that stats showed the written word becoming all but obsolete, replaced by moving images and speech.

“The best way to tell stories in this world, where so much information is coming at us, actually is video,” Mendelsohn said. “It conveys so much more information in a much quicker period. So actually the trend helps us to digest much more information.”

Maybe this is coming from deep within the literacy bubble, but:

Text is surprisingly resilient. It’s cheap, it’s flexible, it’s discreet. Human brains process it absurdly well considering there’s nothing really built-in for it. Plenty of people can deal with text better than they can spoken language, whether as a matter of preference or necessity. And it’s endlessly computable — you can search it, code it. You can use text to make it do other things.

In short, all of the same technological advances that enable more and more video, audio, and immersive VR entertainment also enable more and more text. We will see more of all of them as the technological bottlenecks open up.

And text itself will get weirder, its properties less distinct, as it reflects new assumptions and possibilities borrowed from other tech and media. It already has! Text can be real-time, text can be ephemeral — text has taken on almost all of the attributes we always used to distinguish speech, but it’s still remained text. It’s still visual characters registered by the eye standing in for (and shaping its own) language.

Because nothing has proved as invincible as writing and literacy. Because text is just so malleable. Because it fits into any container we put it in. Because our world is supersaturated in it, indoors and out. Because we have so much invested in it. Because nothing we have ever made has ever rewarded our universal investment in it more. Unless our civilization fundamentally collapses, we will never give up writing and reading.

We’re still not even talking to our computers as often as we’re typing on our phones. What logs the most attention-hours — i.e., how media companies make their money — is not and has never been the universe of communications.

(And my god — the very best feature Facebook Video has, what’s helping that platform eat the world — is muted autoplay video with automatic text captions. Forget literature — even the stupid viral videos people watch waiting for the train are better when they’re made with text!)

Nothing is inevitable in history, media, or culture — but literacy is the only thing that’s even close. Bet for better video, bet for better speech, bet for better things we can’t imagine — but if you bet against text, you will lose.

Socials & More