A Map of Fairyland (c. 1920)

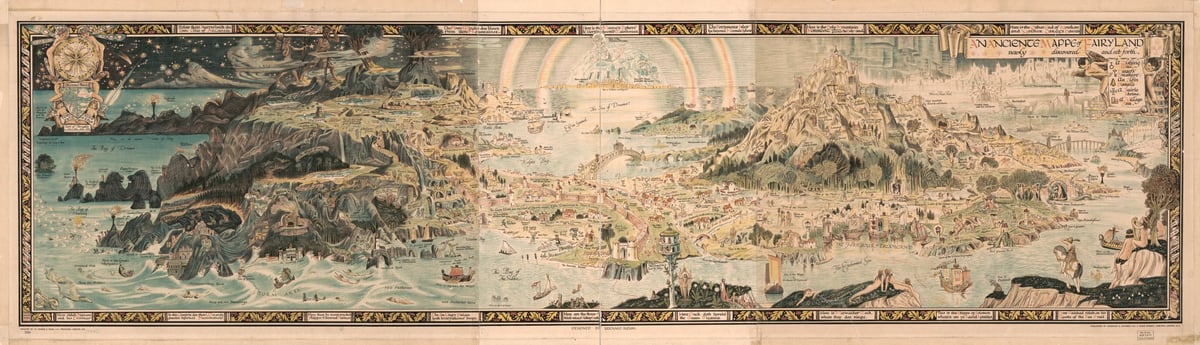

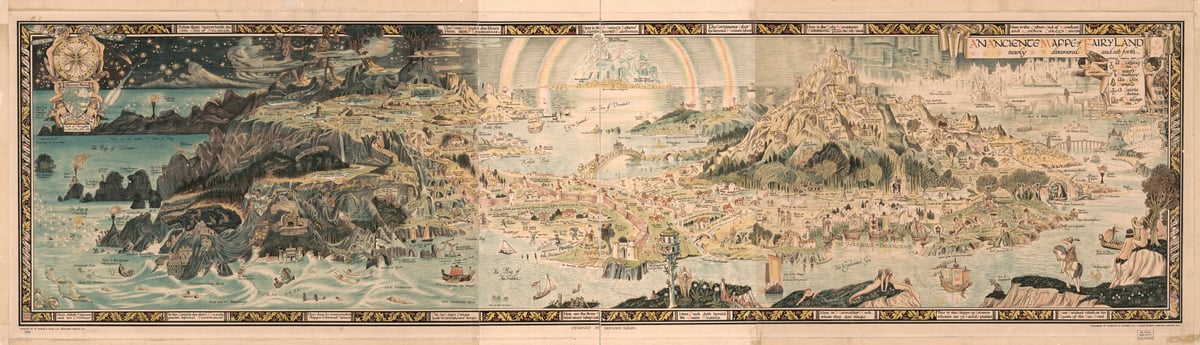

The Library of Congress has a remarkable digitized work in its collection titled “An anciente mappe of Fairyland : newly discovered and set forth,” by Bernard Sleigh, published in London around 1920. Here’s the high-resolution image so you can see some of the detail:

The map aims to be a nearly comprehensive atlas of the world of common English fairy tales, with a few of its own twists and turns. The accompanying guidebook lays out the map’s unique, ontological take on folktales and faerie stories, with the following introductory paragraph (with a quote from Keats’s “Ode to a Nightingale”):

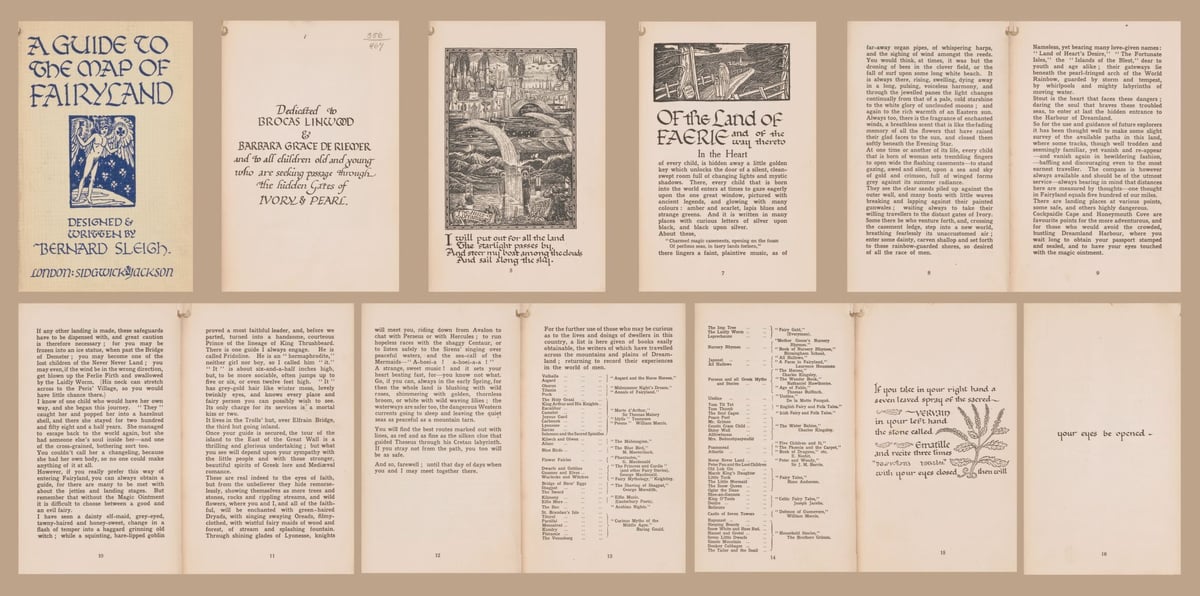

Of the Land of Faerie and of the way thereto

In the Heart of every child, is hidden away a golden key which unlocks the door of a silent, clean-swept room full of changing lights and mystic shadows. There, every child that is born into the world enters at times to gaze eagerly upon the one great window, pictured with ancient legends, and glowing with many colours: amber and scarlet, lapis blues and strange greens. And it is written in many places with curious letters of silver upon black and black upon silver.

About these,

“Charmed magic casements, opening on the foam

Of perilous seas, in faery lands forlorn,”there lingers a faint, plaintive music, as of far-away organ pipes, of whispering harps, and the sighing of wind amongst the reeds. You would think, at times, it was but the droning of bees in the clover field, or the fall of surf upon some long white beach. It is always there, rising, swelling, dying away in a long, pulsing, voiceless harmony, and through the jewelled panes the light changes continually from that of a pale, cold starshine to the white glory of unclouded moons; and again to the rich warmth of an Eastern sun. Always too, there is the fragrance of enchanted winds, a breathless scent that is like the fading memory of all the flowers that have raised their glad faces to the sun, and closed them softly beneath the Evening Star.

At one time or another of its life, every child that is born of woman sets trembling fingers to open wide the flashing casements — to stand gazing, awed and silent, upon a sea and sky of gold and crimson, full of winged forms grey against its summer radiance.

It goes on like this. I hope you find it charming. (I do.)

One of the many things this is useful for, besides its own right, is in understanding the cultural mentality in which works like The Lord of the Rings, CS Lewis’s writings, Walt Disney’s films, and the like were shaped. There was a real grappling with European folk stories, from the 19th century onwards, but the 20th century added a metaphysical dimension, a desire to make these stories real, to fix them in a place, to give them their own world. I find that desire fascinating, especially coming out of the horrors of World War I, and the destruction of so much of what had been the old Europe.

Socials & More