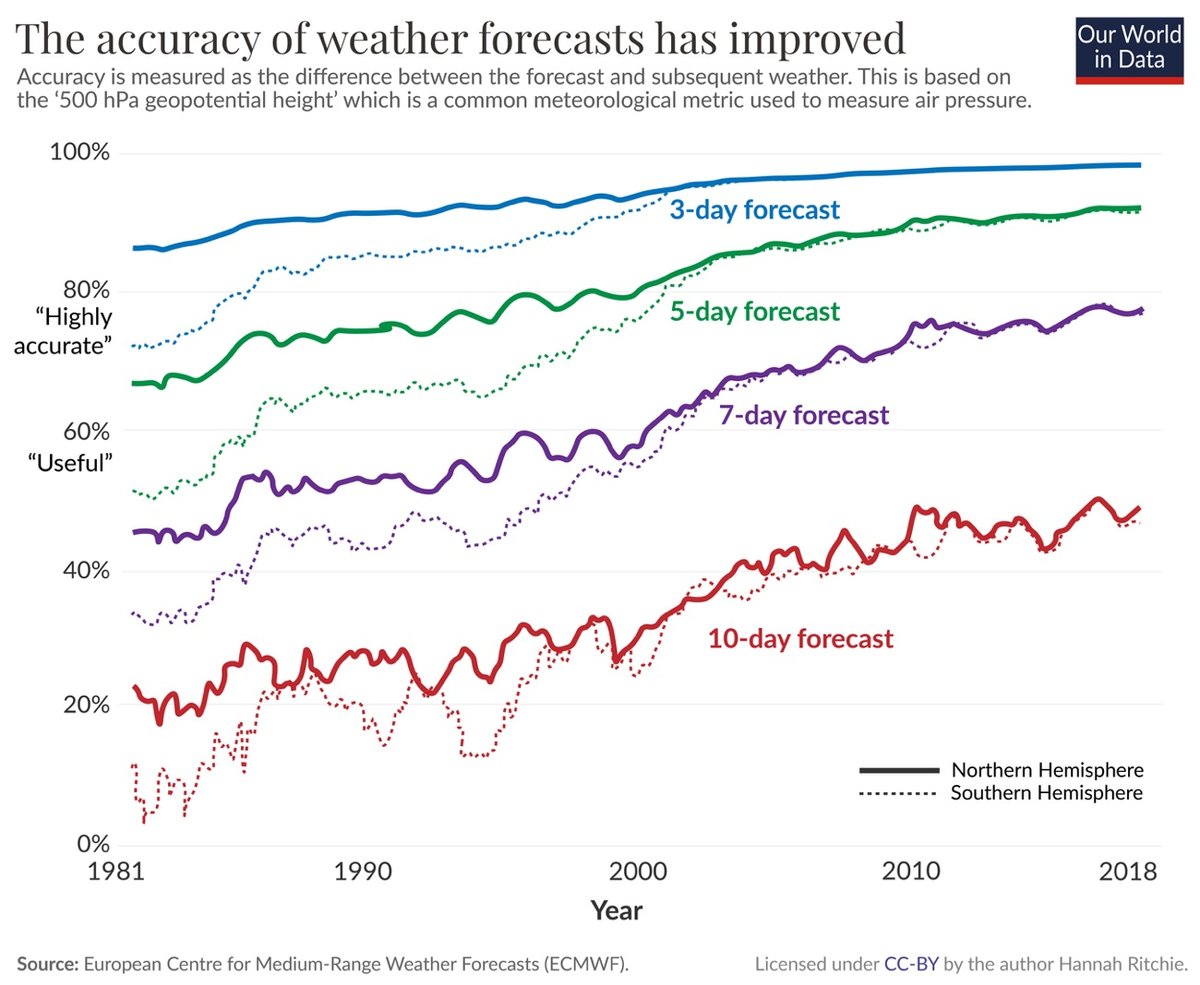

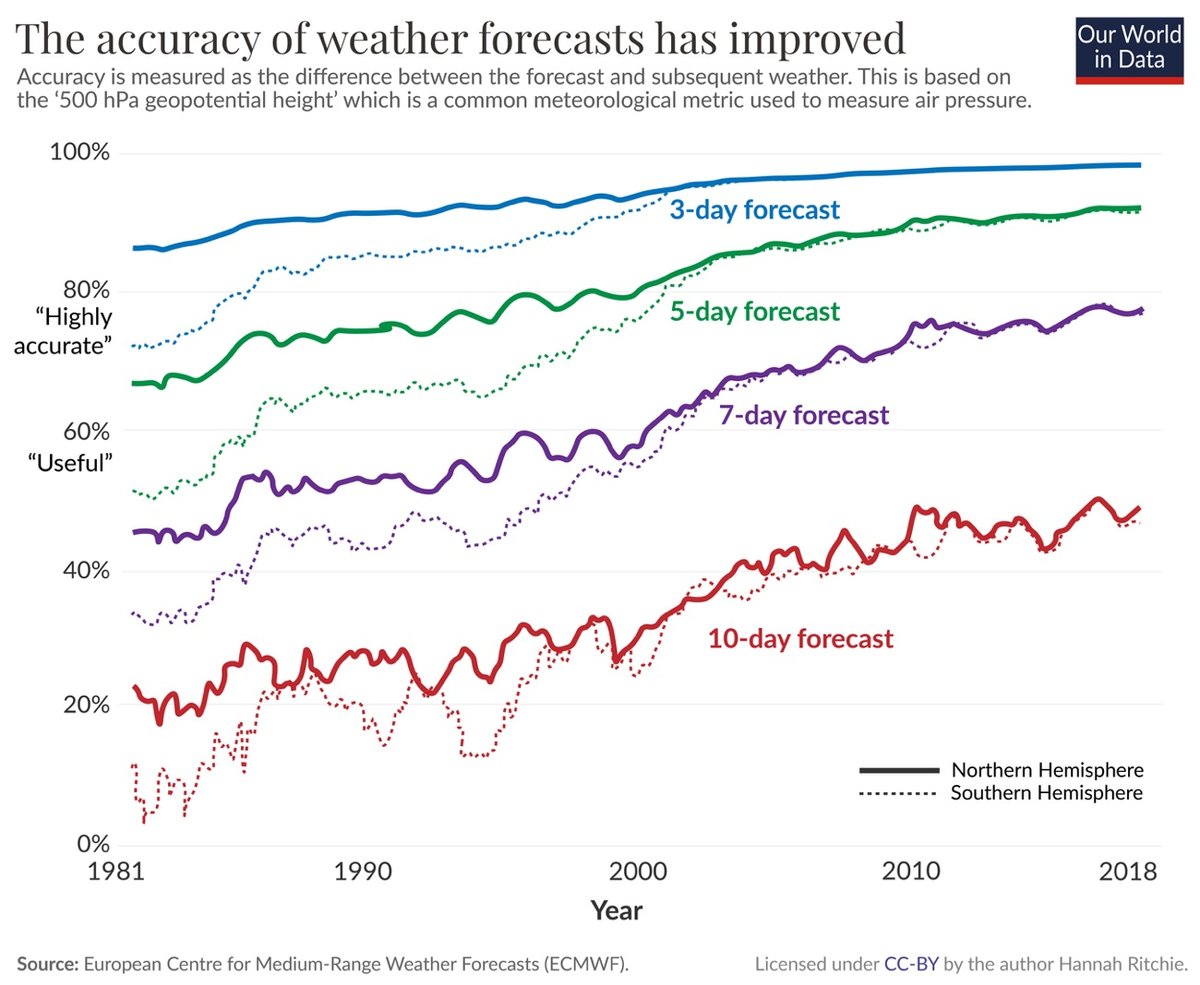

You may not have noticed, but weather forecasts — temperature, precipitation, hurricane tracks — have improved greatly over the past few decades.

Dr. Hannah Ritchie of Our World in Data explains why.

The first big change is that the data has improved. More extensive and higher-resolution observations can be used as inputs into the weather models. This is because we have more and better satellite data, and because land-based stations are covering many more areas around the globe, and at a higher density. The precision of these instruments has improved, too.

These observations are then fed into numerical prediction models to forecast the weather. That brings us to the next two developments. The computers on which these models are run have gotten much faster. Faster speeds are crucial: the Met Office now chunks the world into grids of smaller and smaller squares. While they once modeled the world in 90-kilometer-wide squares, they are now down to a grid of 1.5-kilometer squares. That means many more calculations need to be run to get this high-resolution map. The methods to turn the observations into model outputs have also improved. We’ve gone from very simple visions of the world to methods that can capture the complexity of these systems in detail.

The final crucial factor is how these forecasts are communicated. Not long ago, you could only get daily updates in the daily newspaper. With the rise of radio and TV, you could get a few notices per day. Now, we can get minute-by-minute updates online or on our smartphones.

If you’re in the US, you can see how accurate the weather forecast is in your area by using ForecastAdvisor.

In the early days of the telegraph, station operators began sharing the local weather with each other. As the practice became more widespread, people started to realize that what happened in one location translated to later events in another location. Modern weather forecasting and the concept of weather systems were born.

The operators had discovered something both interesting and paradoxical, the writer Andrew Blum observes in his book The Weather Machine. The telegraph had collapsed time but, in doing so, it had somehow simultaneously created more of it. Now people could see what the future held before it happened; they could know that a storm was on its way hours before the rain started falling or the clouds appeared in the sky. This new, real-time information also did something else, Blum points out. It allowed weather to be visualized as a system, transforming static, localized pieces of data into one large and ever-shifting whole.

Usually, the air nearest the Earth is the warmest and it gets cooler as the altitude increases. But sometimes, there’s a meteorological inversion and colder air gets trapped near the ground with a layer of warmer air on top. While working on a dark sky project, Harun Mehmedinovic shot a time lapse movie of a rare cloud inversion in the Grand Canyon, in which the entire canyon is filled nearly to the brim with fluffy clouds. (via colossal)

With 5 weeks to go in hurricane season, tropical storm Alpha breaks the record for most named storms in the Atlantic Ocean. All of this year’s names have been used up, which means the remaining storms will be named after sequential Greek letters.

Hurricane Ivan generated what is thought to be the tallest wave ever observed. The wave was 91 feet high.

Stay Connected