My favorite contemporary writer is probably Lydia Davis, in no small part because I don’t know if anyone takes a finer care for the language they use, as a writer and reader.

Davis also does double duty as both an original writer of fiction and essays, and a translator of other people’s writings, in multiple languages. In her new collection, Essays 2, she describes her unusual technique:

Although she learned German by immersion, Davis’s preferred method of language acquisition is quite different, and, to an outside observer, demonically challenging: She finds a book published in a language that she does not fully or even partially understand and then tries to figure out what it means.

To improve her Spanish, she digs into a copy of “Las Aventuras de Tom Sawyer.” In some cases the decryption proves easy. Words like “plan” are the same in English and Spanish. In other cases she inductively reasons the meaning of a word after noticing it in different contexts. Hoja initially stumps her when it pops up in the phrase hoja de papel — “hoja of paper.” Later in the book, it occurs in the context of a tree. Finally, Huck wraps a dry hoja around something to make a cigarette, and Davis realizes that only one meaning would work as well with paper as with a tree or a cigarette: “leaf.” Of course, it would be possible to solve the hoja enigma in two seconds by plugging the word into Google, but that would destroy the fun.

I’m (re)learning Italian right now — I sort of learned it backwards the first time, starting with Dante and Petrarch and only now learning how to ask where the bathroom is (dove el gabinetto?) and the difference between coat (cappotto) and hat (cappello). But what remains exciting are the little associations you learn, the conjunctions of phrasing, the possible substitutions of one term for another, the way a question and an answer can reflect the same structure — a map of phonemic possibilities that is also a way of seeing the world. Davis’s method might be impractical for learning a second language, but for a gifted language learner, it seems to put a premium on finding those connections. Which is, indeed, a big part of the fun.

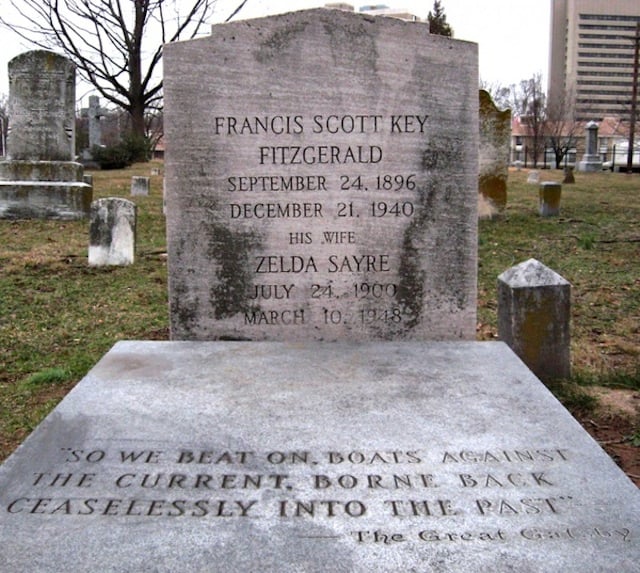

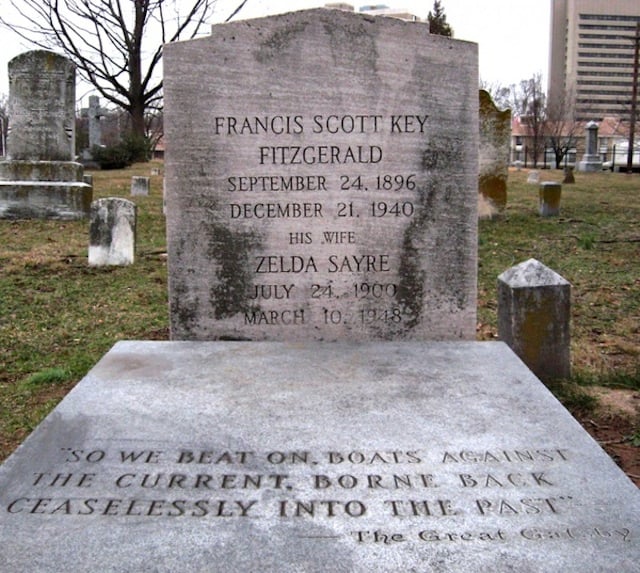

F. Scott Fitzgerald died on December 21, 1940. According to his New York Times obituary, he was felled at 44 by a heart attack that he’d suffered three weeks earlier.

Mr. Fitzgerald in his life and writings epitomized “all the sad young men” of the post-war generation. With the skill of a reporter and ability of an artist he captured the essence of a period when flappers and gin and “the beautiful and the damned” were the symbols of the carefree madness of an age.

An excerpt from The Great Gatsby:

About half way between West Egg and New York the motor road hastily joins the railroad and runs beside it for a quarter of a mile, so as to shrink away from a certain desolate area of land. This is a valley of ashes — a fantastic farm where ashes grow like wheat into ridges and hills and grotesque gardens; where ashes take the forms of houses and chimneys and rising smoke and, finally, with a transcendent effort, of men who move dimly and already crumbling through the powdery air. Occasionally a line of gray cars crawls along an invisible track, gives out a ghastly creak, and comes to rest, and immediately the ash-gray men swarm up with leaden spades and stir up an impenetrable cloud, which screens their obscure operations from your sight.

But above the gray land and the spasms of bleak dust which drift endlessly over it, you perceive, after a moment, the eyes of Doctor T. J. Eckleburg. The eyes of Doctor T. J. Eckleburg are blue and gigantic — their retinas are one yard high. They look out of no face, but, instead, from a pair of enormous yellow spectacles which pass over a nonexistent nose. Evidently some wild wag of an oculist set them there to fatten his practice in the borough of Queens, and then sank down himself into eternal blindness, or forgot them and moved away. But his eyes, dimmed a little by many paintless days, under sun and rain, brood on over the solemn dumping ground.

The valley of ashes is bounded on one side by a small foul river, and, when the drawbridge is up to let barges through, the passengers on waiting trains can stare at the dismal scene for as long as half an hour. There is always a halt there of at least a minute, and it was because of this that I first met Tom Buchanan’s mistress.

(via Riley Dog)

The Guardian has the famous last words of 10 authors. As I am fundamentally opposed to lists in slide show format, especially lists with one list item per slide, the quotations are below. Click through to see the pictures. The chance all of these last words are 100% accurate is something much less than 100%. Points to the Guardian for including 2 women on this list. A lot of lists like this would be male-only.

Samuel Johnson - ‘Iam moriturus’ (I who am about to die)

Lord Byron - ‘Come, come, no weakness; let’s be a man to the last!’

Emily Dickinson - ‘I must go in, the fog is rising’

Robert Louis Stevenson - ‘What’s that? Do I look strange?’

Anton Chekhov - ‘It’s a long time since I drank champagne’

Mark Twain - ‘Death, the only immortal, who treats us alike, whose peace and refuge are for all. The soiled and the pure, the rich and the poor, the loved and the unloved’

Leo Tolstoy - ‘We all reveal … our manifestations … This manifestation is over … That’s all’

Franz Kafka - ‘Dearest Max, my last request: Everything I leave behind me … in the way of diaries, manuscripts, letters (my own and others’), sketches, and so on, (is) to be burned unread’

Virginia Woolf - ‘I feel certain that I’m going mad again …’

James Joyce - ‘Does nobody understand?’

(Via Sagatrope)

Today is my last day at work. And people keep asking me if I’m sad to be leaving…like I should be, I guess. But I’m not sad at all. Not a bit. All the people I hung out with here, all my good friends, are gone already. I don’t like the atmosphere here anymore. I don’t like working here. There’s no challenge anymore…if there was ever a challenge.

So I’m very happy to be leaving. And moving on with my life. Finally.

Stay Connected