kottke.org posts about Zeynep Tufekci

Zeynep Tufekci writes about what makes airplane travel so safe, even when things go wrong (as with the Airbus A350 in Japan and the Alaska Airlines Boeing 737 Max 9 incidents).

Both incidents could have been much worse. And that everyone on both airliners walked away is, indeed, a miracle — but not the kind most people think about. They’re miracles of regulation, training, expertise, effort, constant improvement of infrastructure, as well as professionalism and heroism of the crew.

But these brave and professional men and women were standing on the shoulders of giants: competent bureaucrats; forensic investigators dispatched to accident investigations; large binders (nowadays digital) with hundreds and hundreds of pages of meticulously collected details of every aspect of accidents and near misses; constant training and retraining not just of the pilots but the cabin, ground, traffic control and maintenance crews; and a determined ethos that if something has gone wrong, the reason will be identified and fixed.

As Tufekci notes, when the capitalists are left to their own devices, corners are cut in the pursuit of shareholder value:

The Boeing 737 Max line holds other lessons. After two eerily similar back-to-back crashes in 2018 and 2019, killing 346 people total, the planes were grounded. At first, some rushed to blame inexperienced pilots or software gone awry. But the world soon learned that the real problem had been corporate greed that had taken too many shortcuts while the regulators hadn’t managed to resist the onslaught.

You may have seen the online kerfuffle a few weeks ago about a study that was released recently that indicated that there was no evidence that masks work against respiratory illnesses (see Bret Stephen’s awful ideologically driven piece in the NY Times for instance). As many experts said at the time, that’s not what the review of the studies actually meant and the organization responsible recently apologized and clarified the review’s assertions.

In a typically well-argued and well-researched piece for the NY Times, Zeynep Tufekci explains what the review actually shows and why the science is clear that masks do work.

Scientists routinely use other kinds of data besides randomized reviews, including lab studies, natural experiments, real-life data and observational studies. All these should be taken into account to evaluate masks.

Lab studies, many of which were done during the pandemic, show that masks, particularly N95 respirators, can block viral particles. Linsey Marr, an aerosol scientist who has long studied airborne viral transmission, told me even cloth masks that fit well and use appropriate materials can help.

Real-life data can be complicated by variables that aren’t controlled for, but it’s worth examining even if studying it isn’t conclusive.

Japan, which emphasized wearing masks and mitigating airborne transmission, had a remarkably low death rate in 2020 even though it did not have any shutdowns and rarely tested and traced widely outside of clusters.

David Lazer, a political scientist at Northeastern University, calculated that before vaccines were available, U.S. states without mask mandates had 30 percent higher Covid death rates than those with mandates.

Randomized trials are difficult to do with masks and are not the only way to scientifically prove something. I’m hoping for an update that the entire premise of that Stephens piece is incorrect and will be removed from the Times’ website, but I don’t think it’s going to happen.

Zeynep Tufekci on the H5N1 strain of the avian influenza, which is showing some recent signs of spreading in mammals.

Bird flu — known more formally as avian influenza — has long hovered on the horizons of scientists’ fears. This pathogen, especially the H5N1 strain, hasn’t often infected humans, but when it has, 56 percent of those known to have contracted it have died. Its inability to spread easily, if at all, from one person to another has kept it from causing a pandemic.

But things are changing. The virus, which has long caused outbreaks among poultry, is infecting more and more migratory birds, allowing it to spread more widely, even to various mammals, raising the risk that a new variant could spread to and among people.

Alarmingly, it was recently reported that a mutant H5N1 strain was not only infecting minks at a fur farm in Spain but also most likely spreading among them, unprecedented among mammals. Even worse, the mink’s upper respiratory tract is exceptionally well suited to act as a conduit to humans, Thomas Peacock, a virologist who has studied avian influenza, told me.

The three relevant facts here are: 56% of humans who’ve contracted H5N1 have died, there are signs of spreading among mammals, and that particular mammal is “exceptionally well suited” to pass viral infections along to humans. Tufekci, who attempted to sound the alarm relatively early-on about Covid-19, goes on to urge the world to action about H5N1, before it’s too late. Will we act? (No. The answer is no.)

*sigh*

You know, it’s a little shocking to read about a potential solution to the Fermi paradox on a random February Monday, but here we are.

Over the past several months, I’ve read several pieces about the possible origins of SARS-CoV-2 and have been frustrated with the certainty with which folks who should know better have embraced the “lab leak hypothesis”. So, I was happy to see Zeynep Tufekci’s characteristically even-handed and comprehensive overview of the evidence about the virus’s origins in the NY Times.

While the Chinese government’s obstruction may keep us from knowing for sure whether the virus, SARS-CoV-2, came from the wild directly or through a lab in Wuhan or if genetic experimentation was involved, what we know already is troubling.

Years of research on the dangers of coronaviruses, and the broader history of lab accidents and errors around the world, provided scientists with plenty of reasons to proceed with caution as they investigated this class of pathogens. But troubling safety practices persisted.

Worse, researchers’ success at uncovering new threats did not always translate into preparedness.

Even if the coronavirus jumped from animal to human without the involvement of research activities, the groundwork for a potential disaster had been laid for years, and learning its lessons is essential to preventing others.

Is it possible that SARS-CoV-2 came from a lab? Yes. Is it probable? We can’t know that right now. It’s a tantalizing puzzle involving a possible cover-up, but irresponsibly assigning certainty to the situation does no one but attention-seeking pundits any good.

Since yesterday’s announcement, I’d been feeling uneasy about the CDC’s decision to update its guidance to state that fully vaccinated people don’t need to wear masks in most situations indoors or out. Zeynep Tufekci’s piece in the Times nails why.

It’s difficult for officials to issue rules as conditions evolve and uncertainty continues. So I hesitate to question the agency’s approach. But it’s not clear whether it was responding to scientific evidence or public clamor to lift state and local mandates, which the C.D.C. said could remain in place.

It might have been better to have kept up indoor mask mandates to help suppress the virus for maybe as little as a few more weeks.

The C.D.C. could have set metrics to measure such progress, saying that guidelines would be maintained until the number of cases or the number vaccinations reached a certain level, determined by epidemiologists.

The vaccine is on its way to controlling Covid-19 in the US — but we’re not there yet. We’re not the UK or Israel…they’re further along in their vaccination campaigns and their daily cases and deaths are way down, warranting behavioral changes. In the US, over 600 people/day are still dying of Covid-19 and our case positivity rate is still above 3%. Too many people, including almost all children, are still vulnerable and as Tufekci says, the CDC could have waited a few more weeks to more quickly drive down the virus levels.

Update: The CDC’s move has been sharply condemned by National Nurses United, the nation’s largest union of registered nurses:

“The union noted that more than 35,000 new cases of coronavirus were being reported each day and that more than 600 people were dying each day. “Now is not the time to relax protective measures, and we are outraged that the C.D.C. has done just that while we are still in the midst of the deadliest pandemic in a century,” Ms. Castillo said.”

And Ken Schultz notes that the needle the CDC is trying to thread here might not work out the way that they’d hoped.

Imagine the social preference ordering is:

1. Unvaccinated wear masks, vaccinated don’t.

2. Everyone wears masks.

3. No one wears masks.

Selfish, short-sighted behavior and the inability to monitor vaccination status mean that, in trying to get #1, you can end up at #3.

So I trust the CDC’s position that #1 is socially desirable from a scientific perspective. But by undermining mask mandates, they have made it more likely that we end up in #3, which science says is still risky. Living with #2 for now respects both science and social science.

In a letter published in The Lancet, a group of scholars argue, with an extensive review of the available evidence, that the primary mode of transmission from human to human of the virus responsible for Covid-19 is via aerosols, not through larger particles called droplets or through fomites (transfer from surfaces). Here are three of their ten reasons why:

Third, asymptomatic or presymptomatic transmission of SARS-CoV-2 from people who are not coughing or sneezing is likely to account for at least a third, and perhaps up to 59%, of all transmission globally and is a key way SARS-CoV-2 has spread around the world, supportive of a predominantly airborne mode of transmission. Direct measurements show that speaking produces thousands of aerosol particles and few large droplets, which supports the airborne route.

Fourth, transmission of SARS-CoV-2 is higher indoors than outdoors and is substantially reduced by indoor ventilation. Both observations support a predominantly airborne route of transmission.

Fifth, nosocomial infections have been documented in health-care organisations, where there have been strict contact-and-droplet precautions and use of personal protective equipment (PPE) designed to protect against droplet but not aerosol exposure.

The letter concludes with a plea by the authors for public health officials to finally embrace this reality: “The public health community should act accordingly and without further delay.”

I can’t believe we’re actually still arguing about this. One of the authors, Jose-Luis Jimenez, wrote this seminal Time magazine piece that provided the smoke analogy that is the mental model I’ve been using to think about potential risks during the pandemic.

When it comes to COVID-19, the evidence overwhelmingly supports aerosol transmission, and there are no strong arguments against it. For example, contact tracing has found that much COVID-19 transmission occurs in close proximity, but that many people who share the same home with an infected person do not get the disease. To understand why, it is useful to use cigarette or vaping smoke (which is also an aerosol) as an analog. Imagine sharing a home with a smoker: if you stood close to the smoker while talking, you would inhale a great deal of smoke. Replace the smoke with virus-containing aerosols, which behave very similarly, and the impact is similar: the closer you are to someone releasing virus-carrying aerosols, the more likely you are to breathe in larger amounts of virus. We know from detailed, rigorous studies that when individuals talk in close proximity, aerosols dominate transmission and droplets are nearly negligible.

Another of the authors, Zeynep Tufekci, has been arguing the case for aerosols (and masks & overdispersion) since early in the pandemic, and she succinctly explained in a Twitter thread how predominantly aerosol transmission fits with the mitigation methods that have really worked around the world:

Airborne transmission unites three things crucial to recognize for effective COVID-19 mitigation: transmission without symptoms (thus aerosols), clusters driving the epidemic (also aerosols) and masks/ventilation indoors being key (hey, also aerosols). This framework is coherent.

Her whole thread is worth a read — like this bit about how other respiratory pathogens are likely spread by aerosols and not droplets (as commonly believed):

Fascinatingly, you search the scientific record high and low, but there really is little to no direct evidence for gravity-sprayed droplets being predominant mode of transmission for respiratory illnesses outside of coughing/sneezing. It’s many… assumptions. Like a tradition.

If any good comes out of the pandemic at all, a better and more useful scientific understanding of how respiratory pathogens are transmitted would be a good start.

Update: One of the authors, Trisha Greenhalgh, responds succinctly to criticisms of the paper in this Twitter thread.

Criticism 1: “The paper is just opinion, and several authors aren’t even doctors.”

Response: No. It’s well-researched scholarly argument, produced by an interdisciplinary team of 6 professors including 3 docs, 2 aerosol scientists and 1 social scientist.

Zeynep Tufekci has written an important piece for The Atlantic on the mistakes that the media, public health officials, and the public keep making during the pandemic and how we can learn from them. A big one for me is how scientists & other public health officials and agencies communicate their knowledge to the public and how the media interprets and amplifies those messages.

Thus, on January 14, 2020, the WHO stated that there was “no clear evidence of human-to-human transmission.” It should have said, “There is increasing likelihood that human-to-human transmission is taking place, but we haven’t yet proven this, because we have no access to Wuhan, China.” (Cases were already popping up around the world at that point.) Acting as if there was human-to-human transmission during the early weeks of the pandemic would have been wise and preventive.

Later that spring, WHO officials stated that there was “currently no evidence that people who have recovered from COVID-19 and have antibodies are protected from a second infection,” producing many articles laden with panic and despair. Instead, it should have said: “We expect the immune system to function against this virus, and to provide some immunity for some period of time, but it is still hard to know specifics because it is so early.”

Similarly, since the vaccines were announced, too many statements have emphasized that we don’t yet know if vaccines prevent transmission. Instead, public-health authorities should have said that we have many reasons to expect, and increasing amounts of data to suggest, that vaccines will blunt infectiousness, but that we’re waiting for additional data to be more precise about it. That’s been unfortunate, because while many, many things have gone wrong during this pandemic, the vaccines are one thing that has gone very, very right.

This pair of statements she highlights — “no clear evidence of human-to-human transmission” and “There is increasing likelihood that human-to-human transmission is taking place, but we haven’t yet proven this, because we have no access to Wuhan, China” — are both factually true but the second statement is so much more helpful, useful, and far less likely to be misinterpreted by people who aren’t scientists that making the first statement is almost negligent.

You probably read something yesterday, maybe just a headline, about Moderna’s Covid-19 vaccine being “six times less effective” against the B.1.351 coronavirus variant first identified in South Africa. This is, to put it plainly, a bullshit take on what is actually excellent news. This is the important bit, via Stat:

Both the Moderna vaccine and the immunization from Pfizer-BioNTech produce such powerful levels of immune protection — generating higher levels of antibodies on average than people who recover from a Covid-19 infection have — that they should be able to withstand some drop in their potency without really losing their ability to guard people from getting sick.

“There is a very slight, modest diminution in the efficacy of a vaccine against it, but there’s enough cushion with the vaccines that we have that we still consider them to be effective,” Anthony Fauci, the top U.S. infectious diseases official, said Monday on the “Today” show.

Let’s hear that again: “Both the Moderna vaccine and the immunization from Pfizer-BioNTech produce such powerful levels of immune protection…” These vaccines are so good, so potent, that even this sixfold drop in one measure of the vaccines’ ability to neutralize this one SARS-CoV-2 variant isn’t even enough to significantly reduce their overall protective power.1 That’s the important news here, that’s the very good news, that’s what you should be taking away from this. We have miraculously developed a near-perfect medicine for a plague that has significantly disrupted all human life on Earth and we’re flipping out over some technical details that the experts assure us don’t mean much in terms of overall effectiveness?! No thank you. Not today.

In a Twitter thread, Zeynep Tufekci is tearing her hair out because of the media’s misunderstanding and sensationalization of the “sixfold drop”.

I know people are tired but needless anxiety isn’t helping us. Let’s focus on getting through these months — better masks if indoors with others, more strict attention to our precautions — and the real problem: making more of these amazing vaccines quickly & getting them out there!

I get it, we want to understand but not how it works. Stop worrying about Nab titers. That does NOT mean the vaccine is six times less effective. People whose job it is to worry about it are on it & we just got confirmation: it works against the variants.

Plea to media: this isn’t a good headline. It makes people think the vaccine is six times less effective against the new variants (FALSE!) when the news today is *excellent*: The vaccine continues to work well against the new variants. That’s the headline.

For a much more technical take on the efficacy of the vaccines against variants, see virologist Florian Krammer’s long thread. His conclusion:

mRNA vaccines induce very high neutralizing antibodies after the second shot (consistently in the upper 25-30% of what we see with convalescent sera). If that activity is reduced by 10-fold, it is still decent neutralizing activity that will very likely protect. Furthermore, we know that the mRNA vaccines are already protective after the first shot when neutralizing antibody titers are low or undetectable in most individuals.

There is a concern here and it’s that B.1.351 or B.1.1.7 might mutate into variants that are significantly resistant against the vaccines’ good effects. Krammer again:

First, we need to do what every good scientist is praying for a year now: We need to cut down on virus circulation. The more the virus replicates, the more infections there are the higher are the chances for new variants to arise. Also, we need to try and contain B.1.351 and B.1.1.248/P.1 as much as possible.

That’s why, aside from preventing hundreds of thousands of deaths in the next several months, getting these vaccines into people’s arms is so important: the less the virus spreads, the less opportunity it will have to mutate into something even more dangerous. The US vaccination effort is slowly ramping up — we’re at an average of 1.3 million doses per day right now and the trend is heading in the right direction. We can get this done!

So what can you do about this right now? 1. Stop worrying about the variants until the experts let us know we have something to worry about. 2. If you are eligible for the vaccine, get it! 3. Spread the word about vaccine availability in your area. Yesterday Vermont opened signups for vaccination appointments for all Vermonters 75 and older, and I texted/emailed everyone I could think of who was over 75 or who had parents/relatives/friends who are over 75 to urge them to sign up or spread the word. 4. Continue to wear a mask (a better one if possible), wash your hands, social distance, stay home when possible, don’t spend time indoors w/ strangers, etc. Thanks to these remarkable vaccines, real relief is in sight — let’s keep on track and see this thing through.

In an opinion piece for the NY Times, Zeynep Tufekci and epidemiologist Michael Mina are urging for new trials of the Moderna and Pfizer/BioNTech Covid-19 vaccines to begin immediately to see how effective a single dose might be in preventing new infections. If the trials do indicate that a single dose works, that would effectively double the number of people we could vaccinate within a certain time period, saving countless lives in the US and worldwide.

Both vaccines are supposed to be administered in two doses, a prime and a booster, 21 days apart for Pfizer and 28 days for Moderna. However, in data provided to the F.D.A., there are clues for a tantalizing possibility: that even a single dose may provide significant levels of protection against the disease.

If that’s shown to be the case, this would be a game changer, allowing us to vaccinate up to twice the number of people and greatly alleviating the suffering not just in the United States, but also in countries where vaccine shortages may take years to resolve.

But to get there — to test this possibility — we must act fast and must quickly acquire more data.

For both vaccines, the sharp drop in disease in the vaccinated group started about 10 to 14 days after the first dose, before receiving the second. Moderna reported the initial dose to be 92.1 percent efficacious in preventing Covid-19 starting two weeks after the initial shot, when the immune system effects from the vaccine kick in, before the second injection on the 28th day

That raises the question of whether we should already be administrating only a single dose. But while the data is suggestive, it is also limited; important questions remain, and approval would require high standards and more trials.

The piece concludes: “The possibility of adding hundreds of millions to those who can be vaccinated immediately in the coming year is not something to be dismissed.”

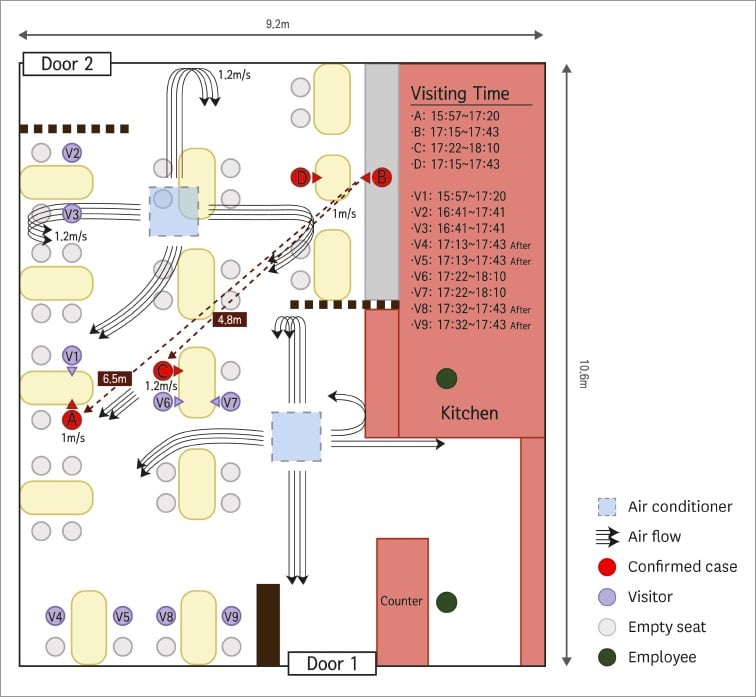

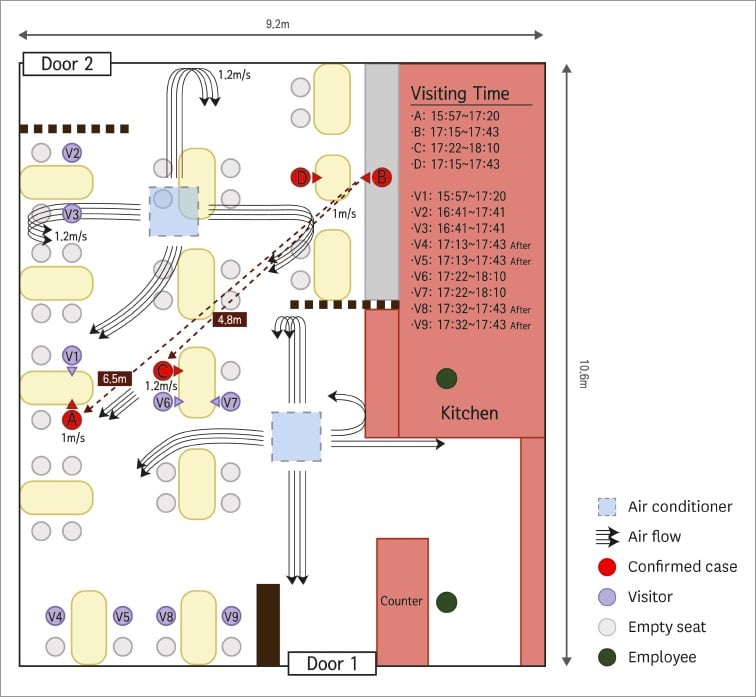

Zeynep Tufekci reports on a small study from Korea that has big implications on how we think about transmission of SARS-CoV-2. Scientists traced two cases back to a restaurant and discovered that transmission had occurred over quite a long distance in a very short period of time.

If you just want the results: one person (Case B) infected two other people (case A and C) from a distance away of 6.5 meters (~21 feet) and 4.8m (~15 feet). Case B and case A overlapped for just five minutes at quite a distance away. These people were well beyond the current 6 feet / 2 meter guidelines of CDC and much further than the current 3 feet / one meter distance advocated by the WHO. And they still transmitted the virus.

As Tufekci goes on to explain, the way they figured this out was quite clever: they contact traced, used CCTV footage from the restaurant, recreated the airflow in the space, and verified the transmission chain with genome sequencing. Here’s a seating diagram that shows the airflow in relation to where everyone was sitting:

Someone infecting another person 21 feet away in only five minutes while others who were closer for longer went uninfected is an extraordinary claim and they absolutely nailed it down. As Sherlock Holmes said: “Once you eliminate the impossible, whatever remains, no matter how improbable, must be the truth.” And the truth is that in some cases, the recommended 6 feet of distance indoors is not sufficient when people aren’t wearing masks. Airflow matters. Ventilation matters. Which way people are facing matters. How much people are talking/laughing/yelling/singing matters. Masks matter. 6 feet of distance does not confer magical protection. All that can make it tough to figure out if certain situations are safe or not, but for me it’s an easy calculation: absolutely no time indoors with other people not wearing masks. Period. As Tufekci concludes:

I think there are three broad lessons here. One, small data can be extremely illuminating. Two, air flow and talking seem to matter a great deal. Three, sadly, indoor dining and any activity where people are either singing or huffing and puffing (like a gym) indoors, especially with poor ventilation, clearly remains high risk.

Read her whole post — as she says, it’s “perhaps one of the finest examples of shoe-leather epidemiology I’ve seen since the beginning of the pandemic”.

Zeynep Tufekci says that a devastating third pandemic surge is upon us and that It’s Time to Hunker Down. She leads with the good news (vaccines, treatments, knowledge, testing capacity & quickness) but notes that with winter coming and a high baseline of cases from a summer not spent in preparation, now is the time to really knuckle down so that we can get to the finish line.

Whatever the causes, public-health experts knew a fall and winter wave was a high likelihood, and urged us to get ready.

But we did not.

The best way to prepare would have been to enter this phase with as few cases as possible. In exponential processes like epidemics, the baseline matters a great deal. Once the numbers are this large, it’s very easy for them to get much larger, very quickly — and they will. When we start with half a million confirmed cases a week, as we had in mid-October, it’s like a runaway train. Only a few weeks later, we are already at about 1 million cases a week, with no sign of slowing down.

Americans are reporting higher numbers of contacts compared with the spring, probably because of quarantine fatigue and confusing guidance. It’s hard to keep up a restricted life. But what we’re facing now isn’t forever.

It’s time to buckle up and lock ourselves down again, and to do so with fresh vigilance. Remember: We are barely nine or 10 months into this pandemic, and we have not experienced a full-blown fall or winter season. Everything that we may have done somewhat cautiously — and gotten away with — in summer may carry a higher risk now, because the conditions are different and the case baseline is much higher.

Citing international precedent and America’s anti-majoritarian systems, Zeynep Tufekci argues that the next authoritarian who runs for President will be much more competent and dangerous.

The Electoral College and especially the Senate are anti-majoritarian institutions, and they can be combined with other efforts to subvert majority rule. Leaders and parties can engage in voter suppression and break norms with some degree of bipartisan cooperation across the government. In combination, these features allow for players to engage in a hardball kind of minority rule: Remember that no Republican president has won the popular vote since 2004, and that the Senate is structurally prone to domination by a minority. Yet Republicans have tremendous power. This dynamic occurs at the local level, too, where gerrymandering allows Republicans to inflate their representation in state legislatures.

The situation is a perfect setup, in other words, for a talented politician to run on Trumpism in 2024. A person without the eager Twitter fingers and greedy hotel chains, someone with a penchant for governing rather than golf. An individual who does not irritate everyone who doesn’t already like him, and someone whose wife looks at him adoringly instead of slapping his hand away too many times in public. Someone who isn’t on tape boasting about assaulting women, and who says the right things about military veterans. Someone who can send appropriate condolences about senators who die, instead of angering their state’s voters, as Trump did, perhaps to his detriment, in Arizona. A norm-subverting strongman who can create a durable majority and keep his coalition together to win more elections.

You should also read Tufekci’s related thread, where she responds to some comments and criticism of the piece.

This isn’t some rare thing that just happened because of weird circumstances. This is a playbook that works. This is a global playbook on the rise. This is a playbook found in America’s past, too. Realism is the true basis for hope.

We have to keep pushing to make sure no populist authoritarians ever get their hands on the Presidency again.

Zeynep Tufekci says that we are paying too much attention to the R value of SARS-CoV-2 (basically the measure of its contagiousness) and not nearly enough attention to the k value (“whether a virus spreads in a steady manner or in big bursts, whereby one person infects many, all at once”).

There are COVID-19 incidents in which a single person likely infected 80 percent or more of the people in the room in just a few hours. But, at other times, COVID-19 can be surprisingly much less contagious. Overdispersion and super-spreading of this virus is found in research across the globe. A growing number of studies estimate that a majority of infected people may not infect a single other person. A recent paper found that in Hong Kong, which had extensive testing and contact tracing, about 19 percent of cases were responsible for 80 percent of transmission, while 69 percent of cases did not infect another person. This finding is not rare: Multiple studies from the beginning have suggested that as few as 10 to 20 percent of infected people may be responsible for as much as 80 to 90 percent of transmission, and that many people barely transmit it.

We’ve known, or at least suspected, this about SARS-CoV-2 for awhile now — I linked to two articles about superspreading back in May and June — but Tufekci says we have not adjusted our thinking about what that means for prevention. We should be avoiding superspreading environments/events (“Avoid Crowding, Indoors, low Ventilation, Close proximity, long Duration, Unmasked, Talking/singing/Yelling”), doing backwards contact tracing, and rapid testing.

In an overdispersed regime, identifying transmission events (someone infected someone else) is more important than identifying infected individuals. Consider an infected person and their 20 forward contacts-people they met since they got infected. Let’s say we test 10 of them with a cheap, rapid test and get our results back in an hour or two. This isn’t a great way to determine exactly who is sick out of that 10, because our test will miss some positives, but that’s fine for our purposes. If everyone is negative, we can act as if nobody is infected, because the test is pretty good at finding negatives. However, the moment we find a few transmissions, we know we may have a super-spreader event, and we can tell all 20 people to assume they are positive and to self-isolate-if there is one or two transmissions, it’s likely there’s more exactly because of the clustering behavior. Depending on age and other factors, we can test those people individually using PCR tests, which can pinpoint who is infected, or ask them all to wait it out.

Part of the problem is that dispersion and its effects aren’t all that intuitive.

Overdispersion makes it harder for us to absorb lessons from the world because it interferes with how we ordinarily think about cause and effect. For example, it means that events that result in spreading and non-spreading of the virus are asymmetric in their ability to inform us. Take the highly publicized case in Springfield, Missouri, in which two infected hairstylists, both of whom wore masks, continued to work with clients while symptomatic. It turns out that no apparent infections were found among the 139 exposed clients (67 were directly tested; the rest did not report getting sick). While there is a lot of evidence that masks are crucial in dampening transmission, that event alone wouldn’t tell us if masks work. In contrast, studying transmission, the rarer event, can be quite informative. Had those two hairstylists transmitted the virus to large numbers of people despite everyone wearing masks, it would be important evidence that, perhaps, masks aren’t useful in preventing super-spreading.

The piece is an important read and interesting throughout: just read the whole thing.

Josh Marshall argues provocatively and persuasively that news media, law enforcement, and everyone else should name the offenders in these mass shootings, in part because the refusal has become an empty sort of action that people can take to “help”.

It is a grand evasion because we need to make ourselves feel better by finding a way to think we are doing ‘something’ even though we’re unwilling to do anything that actually matters. Except for those immediately affected or those in the tightly defined communities affected we also shouldn’t give ourselves the solace of watching teary-eyed memorials or all the rest. Again, as a society we’ve made our decision. I would go so far as to say that it’s good for us to know Mercer’s name since we are in fact his accomplices. It’s good that we know each other.

Withholding knowledge is not the way forward.

Update: From the NY Times back in August, Zeynep Tufekci writes: The Virginia Shooter Wanted Fame. Let’s Not Give It to Him.

This doesn’t mean censoring the news or not reporting important events of obvious news value. It means not providing the killers with the infamy they seek. It means somber, instead of lurid and graphic, coverage, and a focus on victims. It means not putting the killer’s face on loop. It means minimizing or not using the killers’ names, as I have done here. It means not airing snuff films, or making them easily accessible on popular sites. It means holding back reporting of details such as the type of gun, ammunition, angle of attack and the protective gear the killer might have worn. Such detailed reporting can give the next killer a concrete road map.

(via @riondotnu)

Update: Read all the way to the bottom of this Mother Jones article for ways that they have changed how they report on mass shootings.

Report on the perpetrator forensically and with dispassionate language. Avoid terms like “lone wolf” and “school shooter,” which may carry cachet with young men aspiring to attack. Instead use “perpetrator,” “act of lone terrorism,” and “act of mass murder.”

Stay Connected