The Real Lord of the Flies

For his new book, Humankind: A Hopeful History, Rutger Bregman uncovered the real-life story of 6 schoolboys who were stranded on a Pacific island for 15 months in 1965-66. What he learned was not the familiar tale of savagery & death told in William Golding’s novel Lord of the Flies. Instead, the boys cooperated and thrived.

But “by the time we arrived,” Captain Warner wrote in his memoirs, “the boys had set up a small commune with food garden, hollowed-out tree trunks to store rainwater, a gymnasium with curious weights, a badminton court, chicken pens and a permanent fire, all from handiwork, an old knife blade and much determination.” While the boys in Lord of the Flies come to blows over the fire, those in this real-life version tended their flame so it never went out, for more than a year.

On Twitter, Bregman shared how he came to learn about this story:

As a proper investigative journalist, I started Googling. Search terms: ‘Kids shipwrecked’. ‘Real-life Lord of the Flies’ etc. After a while, I came across a blog that told this story.

Wow, I thought. If this really happened, then why isn’t it a super famous story? The article did not provide sources. After a couple of hours, I discovered that it came from a book by the anarchist Colin Ward from 1988. He cited an Italian politician Susanna Agnelli.

From a second-hand bookshop in the UK, I ordered her 1986 book, got it two weeks later, and found the story on page 94. But again: same details, same wording, no source. At that point I started to think that it probably didn’t happen.

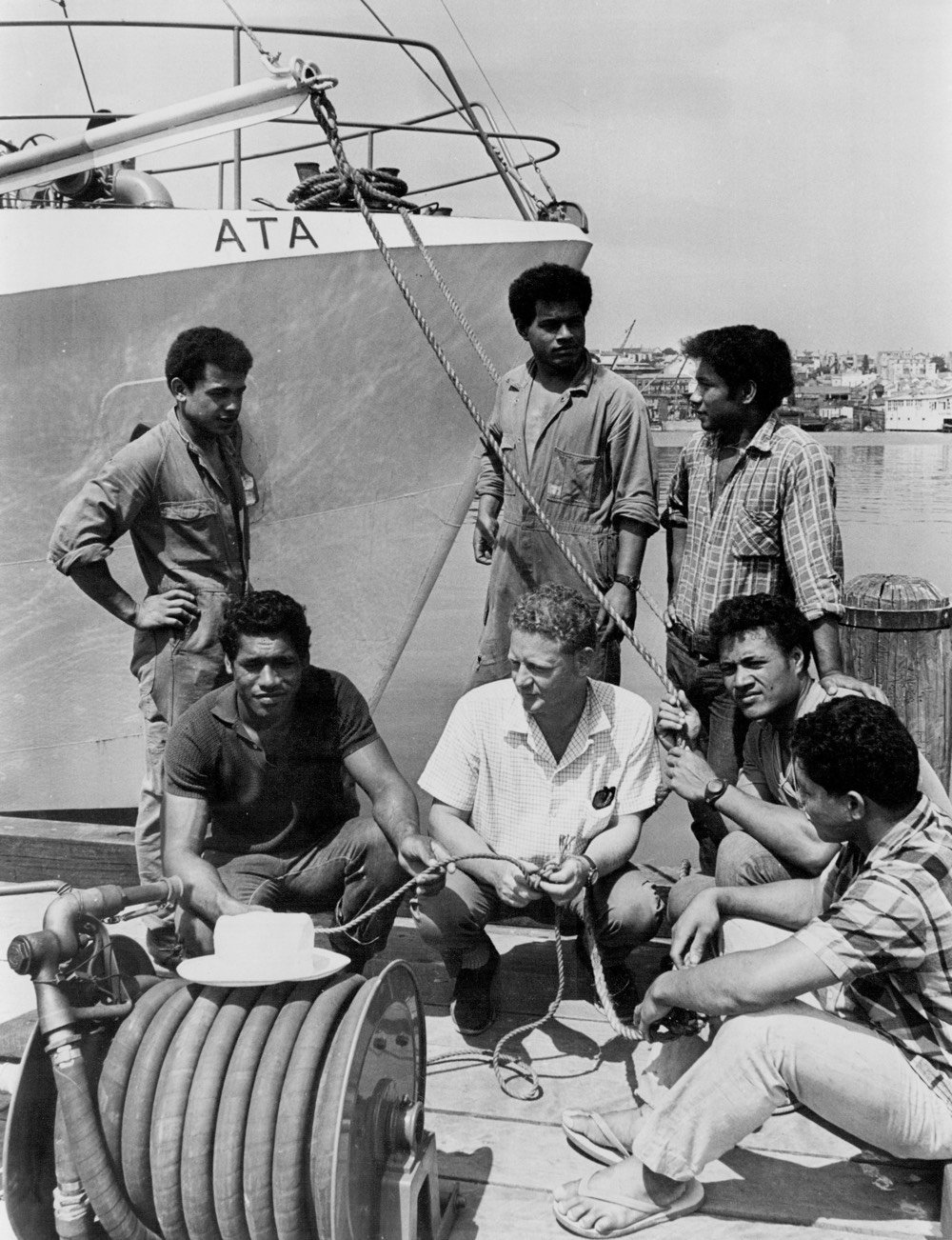

Here’s a photo of the six boys with Peter Warner, the sea captain who rescued them:

After the rescue, Warner hired the boys as crew members and they worked with him for years. you can read more about Bregman and his new book in this related article.

Update: You may have noticed that Bregman’s piece is told from the perspective of the discoverer of a good story and the sea captain who rescued the boys, and there’s actually relatively little from the boys themselves. Tongan writer Meleika Gesa-Fatafehi wrote a pair of threads on Twitter about how problematic it is that a story about six indigenous schoolboys became one about two white men. First of all, the story was not unknown or forgotten:

I’ve been told many stories about (both) my people getting lost by sea and being stuck on either a boat or Island. But I remember this one significantly because the boys were stuck on ‘Ata. I remember it being called the rock Island.

The local culture that the boys grew up in is essential to the story, particularly w/r/t the lesson Bregman wants to assign to it:

Tongans are taught to share from the beginning. You’re also taught to treat everyone like family. You’re taught to survive together not “Everyman to himself”. It’s hard to exist without community. So when one person is ill or hurt, it’s an automatic reaction to help

To heal and to use knowledge passed down to you. This is seen in every aspect of how the boys survived. They created a community, a small family and worked together.

The white boys of LotF cannot relate because of the very fact they are rich white school boys who aren’t from an Island nation.

LotF isn’t what would happen amongst Tongans because of the value system we have. This is true for every Island nation.

Filmmaker Taika Waititi had this to say about a possible film adaptation:

Personally, I think you should prioritize Polynesian (Tongan if possible!) filmmakers as to avoid cultural appropriation, misrepresentation, and to keep the Pasifika voice authentic.

(via @tinakittelty)

Stay Connected