Nazi helmets remade into pots and pans

After World War II, the helmets of German soldiers were refashioned into colanders, pots, and other kitchen utensils. This video from the British Pathé archive shows how the repurposing happened.

This site is made possible by member support. 💞

Big thanks to Arcustech for hosting the site and offering amazing tech support.

When you buy through links on kottke.org, I may earn an affiliate commission. Thanks for supporting the site!

kottke.org. home of fine hypertext products since 1998.

After World War II, the helmets of German soldiers were refashioned into colanders, pots, and other kitchen utensils. This video from the British Pathé archive shows how the repurposing happened.

During the German occupation of France, teenager Adolfo Kaminsky forged thousands of documents for Jews about to be deported to concentration camps. He worked at a shop that dyed clothes and a Jewish resistance cell recruited him because he knew how to remove ink stains, a skill that served him well in altering documents.

If you’re doubting whether you’ve done enough with your life, don’t compare yourself to Mr. Kaminsky. By his 19th birthday, he had helped save the lives of thousands of people by making false documents to get them into hiding or out of the country. He went on to forge papers for people in practically every major conflict of the mid-20th century.

Now 91, Mr. Kaminsky is a small man with a long white beard and tweed jacket, who shuffles around his neighborhood with a cane. He lives in a modest apartment for people with low incomes, not far from his former laboratory.

When I followed him around with a film crew one day, neighbors kept asking me who he was. I told them he was a hero of World War II, though his story goes on long after that.

A remarkable story and a remarkable gentleman. The video above is based on a book Kaminsky’s daughter wrote about him.

During World War II, a group of scientists led by Werner Heisenberg worked on designing a nuclear weapon for Nazi Germany. They were, thankfully, unsuccessful. After the war, the Allies detained ten German scientists in England for six months. Hoping to learn about the German bomb program, they secretly taped the scientists’ conversations. In August 1945, the scientists were told about the US dropping a nuclear bomb on Japan. Here’s a transcript of the resulting reaction and conversation.

Shortly before dinner on the 6th August I informed Professor HAHN that an announcement had been made by the B.B.C. that an atomic bomb had been dropped. HAHN was completely shattered by the news and said that he felt personally responsible for the deaths of hundreds of thousands of people, as it was his original discovery which had made the bomb possible. He told me that he had originally contemplated suicide when he realized the terrible potentialities of his discovery and he felt that now these had been realized and he was to blame. With the help of considerable alcoholic stimulant he was calmed down and we went down to dinner where he announced the news to the assembled guests.

“Professor HAHN” is Otto Hahn, who co-discovered nuclear fission in Germany right before the war and won the 1944 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for it. The rest of the world may have gotten there eventually, but think of how different the war (and resulting Cold War period) would have been if Germany had sequestered their scientific progress a couple years earlier or if Hahn and Lise Meitner had made the discovery a year or two later.

WEIZSÄCKER: I think it’s dreadful of the Americans to have done it. I think it is madness on their part.

HEISENBERG: One can’t say that. One could equally well say “That’s the quickest way of ending the war.”

HAHN: That’s what consoles me.

HAHN: I was consoled when, I believe it was WEIZSÄCKER said that there was now this uranium - I found that in my institute too, this absorbing body which made the thing impossible consoled me because when they said at one time one could make bombs, I was shattered.

WEIZSÄCKER: I would say that, at the rate we were going, we would not have succeeded during this war.

HAHN: Yes.

WEIZSÄCKER: It is very cold comfort to think that one is personally in a position to do what other people would be able to do one day.

I particularly like Heisenberg’s distinction between between theoretical and applied science:

There is a great difference between discoveries and inventions. With discoveries one can always be skeptical and many surprises can take place. In the case of inventions, surprises can really only occur for people who have not had anything to do with it. It’s a bit odd after we have been working on it for five years.

If this stuff interests you at all, I’d highly recommend reading Richard Rhodes’ The Making of the Atomic Bomb. (via real future)

Update: The complete transcripts of the secret recordings were collected into a book called Hitler’s Uranium Club. The story of the Allied sabotage of a key element in producing a German bomb is told in Neal Bascomb’s The Winter Fortress. Alex Wellerstein writes that the Nazis didn’t know very much about the Manhattan Project. (via @CarnegieDeputy, @hellbox, @AtomicHeritage)

In the 1930s, almost a decade before the nation’s young men would be shipped overseas to combat the foul stench of Hitler wafting across Europe, official and unofficial rallies for the Nazi party were held in Madison Square Garden.

Shortly after Adolf Hitler’s appointment as Chancellor of Germany in January 1933, the Nazis consolidated control over the country. Looking to cultivate power beyond the borders of Germany, Deputy Führer Rudolf Hess charged German-American immigrant Heinz Spanknobel with forming a strong Nazi organization in the United States.

Combining two small extant groups, Spanknobel formed Friends of New Germany in July 1933. Counting both German nationals and Americans of German descent among its membership, the Friends loudly advocated for the Nazi cause, storming the offices of New York’s largest German-language paper, countering Jewish boycotts of German businesses and holding swastika-strewn rallies in black-and-white uniforms.

A later group, which only disbanded at the end of 1941, were prominently pro-American and featured iconography of George Washington as “the first Fascist”. (I would have gone for “the Founding Fascist”…catchier.)

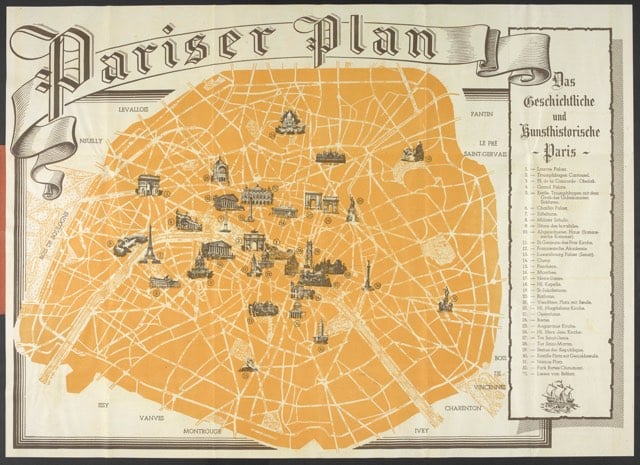

In 1940, Germany published a tourist map of occupied Paris intended for use by German soldiers on leave.

After the end of World War II in Europe, homosexual prisoners of liberated concentration camps were refused reparations and some were even thrown into jail without credit for their time served in the camps. From the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum:

After the war, homosexual concentration camp prisoners were not acknowledged as victims of Nazi persecution, and reparations were refused. Under the Allied Military Government of Germany, some homosexuals were forced to serve out their terms of imprisonment, regardless of the time spent in concentration camps. The 1935 version of Paragraph 175 remained in effect in the Federal Republic (West Germany) until 1969, so that well after liberation, homosexuals continued to fear arrest and incarceration.

After 1945, it was no longer a crime to be Jewish in Germany, but homosexuality was another matter. Paragraph 175 of the German Criminal Code had been on the books since 1871. An English translation of the earliest version read simply:

Unnatural fornication, whether between persons of the male sex or of humans with beasts, is to be punished by imprisonment; a sentence of loss of civil rights may also be passed.

In Germany, homosexuality was considered a crime worthy of up to five years of imprisonment until Paragraph 175 was voided in 1994.

Update: I missed this while writing the post: Paragraph 175 was amended in 1969 to limit enforcement to engaging in homosexual acts with minors (under 21 years). (thx, eric)

Per Betteridge’s law of headlines, the answer to this is “no”, but it’s still an interesting yarn.

Among the many enduring mysteries of this period is the fate of the world’s most famous painting. It seems that Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa was among the paintings found in the Altaussee salt mine in the Austrian alps, which was converted by the Nazis into their secret stolen-art warehouse.

The painting only “seems” to have been found there because contradictory information has come down through history, and the Mona Lisa is not mentioned in any wartime document, Nazi or allied, as having been in the mine. Whether it may have been at Altaussee was a question only raised when scholars examined the postwar Special Operations Executive report on the activities of Austrian double agents working for the allies to secure the mine. This report states that the team “saved such priceless objects as the Louvre’s Mona Lisa”. A second document, from an Austrian museum near Altaussee dated 12 December 1945, states that “the Mona Lisa from Paris” was among “80 wagons of art and cultural objects from across Europe” taken into the mine.

The Mona Lisa was actually stolen in 1911, in one of the cleverest art heists ever pulled.

Matthew Porter’s photo composite Empire on the Platte is arresting.

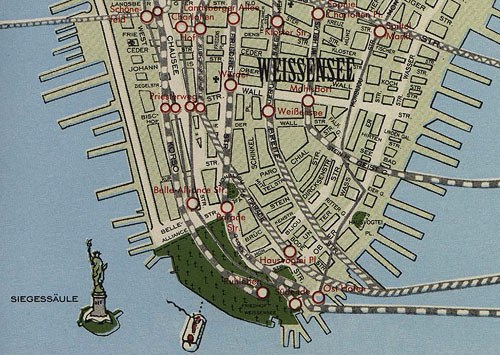

Pairs nicely with Melissa Gould’s Neu-York, “an obsessively detailed alternate-history map, imagining how Manhattan might have looked had the Nazis conquered it in World War II”.

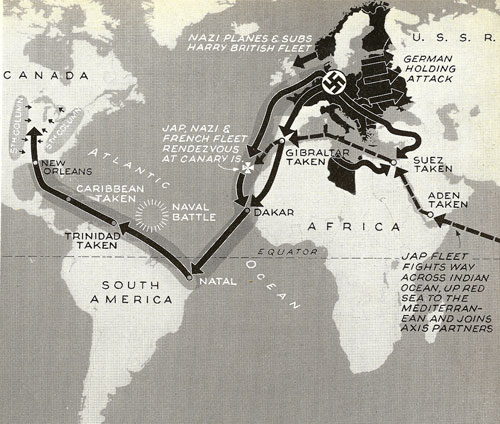

In 1942, Life magazine speculated about what an Axis invasion of North America might look like.

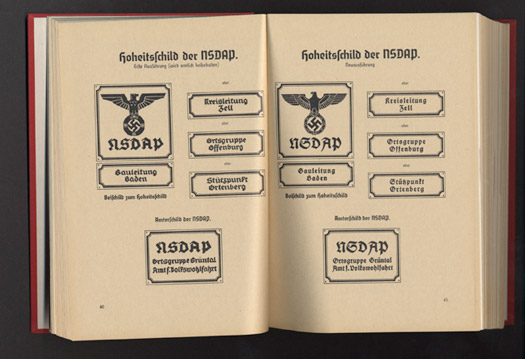

Steven Heller had heard rumors of a Nazi graphics standards manual for years and finally tracked one down.

Published in 1936, The Organizationsbuch der NSDAP (with subsequent annual editions), detailed all aspects of party bureaucracy, typeset tightly in German Blackletter. What interested me, however, were the over 70 full-page, full-color plates (on heavy paper) that provide examples of virtually every Nazi flag, insignia, patterns for official Nazi Party office signs, special armbands for the Reichsparteitag (Reichs Party Day), and Honor Badges. The book “over-explains the obvious” and leaves no Nazi Party organization question, regardless of how minute, unanswered.

A photo album created by an SS officer stationed at Auschwitz has been donated to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. The unique album shows the life and activities of officers at the camp. Compare the SS officer photographs with photographs from an album showing prisoners arriving at the camp. (via nytimes)

Gunter Grass: How I Spent the War, a first-person account of an SS recruit during WWII.

Update: Here’s some biographical information about Grass, who is a Nobel Prize-winning novelist. (thx, red)

A new book, Heil Hitler, The Pig is Dead, deals with humor during Hitler’s reign in Germany. “From an early stage, Germans were well aware of their government’s brutality. And the country wasn’t possessed by ‘evil spirits’ nor was it hypnotised by the Nazis’ brilliant propaganda, he says. Hypnotized people don’t crack jokes.”

Art and genocide…why doesn’t Soviet and Communist Chinese propaganda imagery offend us like Nazi propaganda does? The Stalinist and Maoist regimes were responsible for more deaths than the Nazis.

Stay Connected