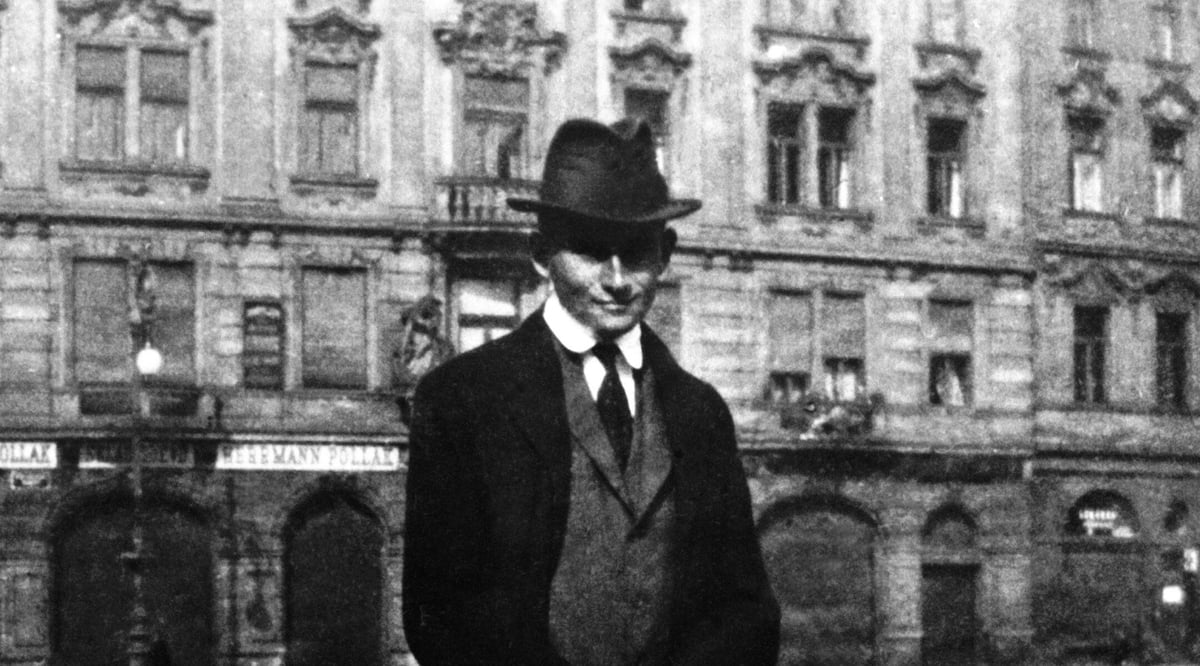

Kafka’s Diaries / The Writer’s Desk as Theater

Franz Kafka’s Diaries, a combination of a private journal and a sketchbook for stories and essays, have been available in English since 1948, but in a much altered form, prepared by Kafka’s friend and literary executor Max Brod (who famously ignored his friend’s instructions to burn whatever remained). Brod tidied up the diaries for publication, removing multiple aborted drafts and excising anything that he thought might be embarrassing.

A new German edition published in 1990 restored some of the chaos to Kafka’s diaries, but it’s only in this year that the unexpurgated diaries have been translated into English, by Ross Benjamin. The overall impression is of a Kafka who is less censored, more frank, more Jewish, and funnier, but also remorseless in his self-upbraiding to write more, to write better, to write something true.

The translation is not always as sure-footed as its predecessor; sometimes its literalness ignores idioms and hews too closely to the original punctuation, producing a clumsy impression where Kafka’s German is as graceful and artful as ever.

Here is Benjamin’s version of one of my favorite early passages of the Diaries, from Notebook 2, written over Christmas Eve and Christmas Day 1910:

24 (December 1910) Now I have taken a closer look at my desk and realized that nothing good can be done on it. There’s so much lying around here, forming a disorder without regularity and without any compatibility of the disordered things, which otherwise makes every disorder bearable. Let there be whatever disorder there may on the green cloth, the same was allowed in the orchestra of old theaters. But the fact that from the standing room…

25 (December 1910)… from the open compartment under the upper part of the desk there are brochures, old newspapers, catalogues picture postcards, letters, all partly torn, partly opened coming out in the form of a staircase, this undignified state spoils everything. Individual relatively huge things in the orchestra appear in the greatest possible activity, as if it were permitted in the auditorium of the theater for the merchant to put his account books in order, the carpenter to hammer, the officer to brandish his saber, the priest to speak to the heart, the scholar to the intellect, the politician to the public spirit, for lovers not to restrain themselves, etc. Only on my desk the shaving mirror stands upright, the way one needs it for shaving, the clothes brush lies with its bristle surface on the cloth, the wallet lies open in case I want to pay, from the key ring a key sticks out ready for work and the tie is still partly looped around the taken-off collar. The next higher open compartment, already hemmed in by the small closed side drawers, is nothing but a junk room, as if the low balcony of the auditorium, basically the most visible part of the theater were reserved for the most vulgar people for old bon vivants, among whom the filth gradually comes from the inside to the outside, coarse fellows who let their feet hang down over the balcony railing, families with so many children that one takes only a brief glance without being able to count them introduce here the filth of poor nurseries (indeed there’s already a trickling in the orchestra) in the dark background sit incurably sick people, fortunately one sees them only when one shines a light in, etc. In this compartment lie old papers I would have long since thrown away if I had a wastepaper basket, pencils with broken points, an empty matchbox, a paperweight from Karlsbad, a ruler with an edge the bumpiness of which would be too awful for a country road, many collar buttons, dull razorblades (for them there is no place in the world), tie clips and another heavy iron paperweight. In the compartment above —

Wretched, wretched and yet well meant. Yes, it’s midnight, but since I’ve slept very well, that is an excuse only insofar as during the day I would have written nothing at all. The burning electric light, the silent apartment, the darkness outside, the last waking moments they give me the right to write and be it even the most wretched things. And this right I use hastily. So that’s who I am.

Stay Connected