The Senate stops Elizabeth Warren from reading a letter from Coretta Scott King

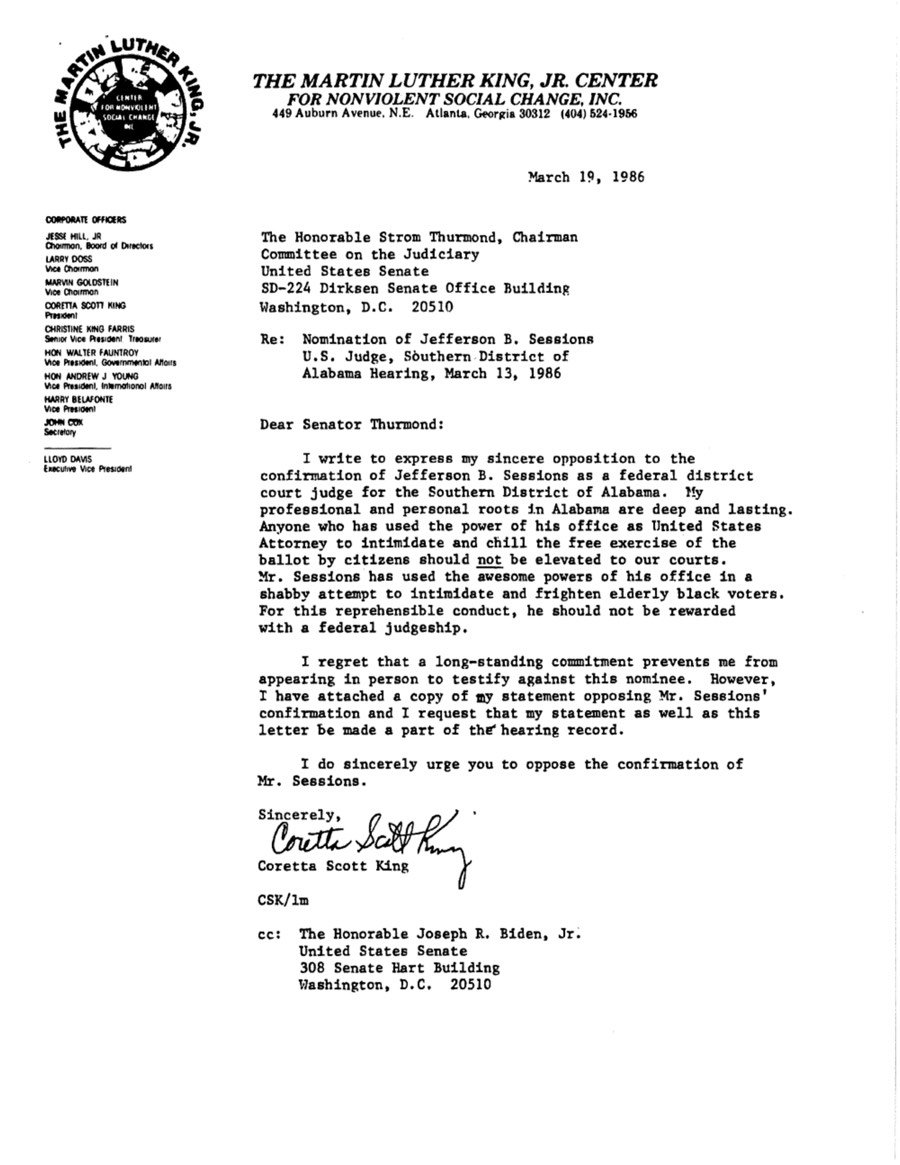

Last night, during the Senate confirmation hearing of Senator Jefferson Beauregard “Jeff” Sessions III1 for Attorney General, Senator Elizabeth Warren attempted to read a letter that Coretta Scott King had written to the Senate Judiciary Committee in 1986 opposing Sessions’ nomination for a federal judgeship (which he did not get).

The first page of the letter appears above and the entire contents may be read here. King pretty plainly states that Sessions abused his position in an attempt to disenfranchise black voters:

Mr. Sessions has used the awesome power of his office to chill the free exercise of the vote by black citizens in the district he now seeks to serve as a federal judge.

Under Senate Rule XIX and after two votes by the full Senate, Warren was barred from speaking and finishing the letter.

When Warren first spoke against Sessions Tuesday night, Sen. Steve Daines, a Republican from Montana, warned her that she was breaking the rules. When she continued anyway, Majority Leader Mitch McConnell retaliated by finding her in violation of Senate Rule XIX — which prevents any senator from using “any form of words [to] impute to another Senator… any conduct or motive unworthy or unbecoming a Senator.”

Warren later read the letter outside of the Senate chambers. How the Senate is supposed to debate the appointment of a Cabinet member without being able to criticize the actions, words, and beliefs of that candidate is left as an exercise to the reader. (Ok, I’ll answer anyway: it’s not supposed to debate. That’s the entire point of the Republicans’ actions w/r/t Trump’s political nominees thus far.)

King’s letter, which Buzzfeed called “a key part of the case against Sessions [in 1986]” was only published earlier this week in part because Judiciary Committee Chairman Strom Thurmond never officially entered it into the congressional record. Thurmond, you may remember, vehemently opposed the civil rights reforms of the 50s and 60s, even going so far as filibustering the Civil Rights Act of 1957 for more than 24 hours and switching political parties because of the Democrats’ support of the 1964 Civil Rights Act.

And Senate Rule XIX? Cornell Law School professor James Grimmelmann notes the precedent:

Let’s be clear on the precedent here: it’s the 1836-44 gag rule that forbade any consideration of abolition in the House.

Racist southern representatives were so frustrated by abolitionist petitions to Congress, that they adopted a series of rules.

All abolitionist petitions would immediately be tabled, and any attempt to introduce them would be prohibited.

From pro-slavery members of the House to Davis to Beauregard to Thurmond to Trump (and Bannon) to Sessions to McConnell (and the nearly all-white Republican majority). Paraphrasing Stephen Hawking, it’s white supremacy all the way down. Gosh, if you’re a black person in America, you might even think the system is tilted against you!

P.S. I like this part of Senate Rule XIX, right at the bottom:

8. Former Presidents of the United States shall be entitled to address the Senate upon appropriate notice to the Presiding Officer who shall thereupon make the necessary arrangements.

I’m not sure what it would accomplish, but seeing a former President address this Senate, after an appropriate period spent kiteboarding, would be pretty fun to watch.

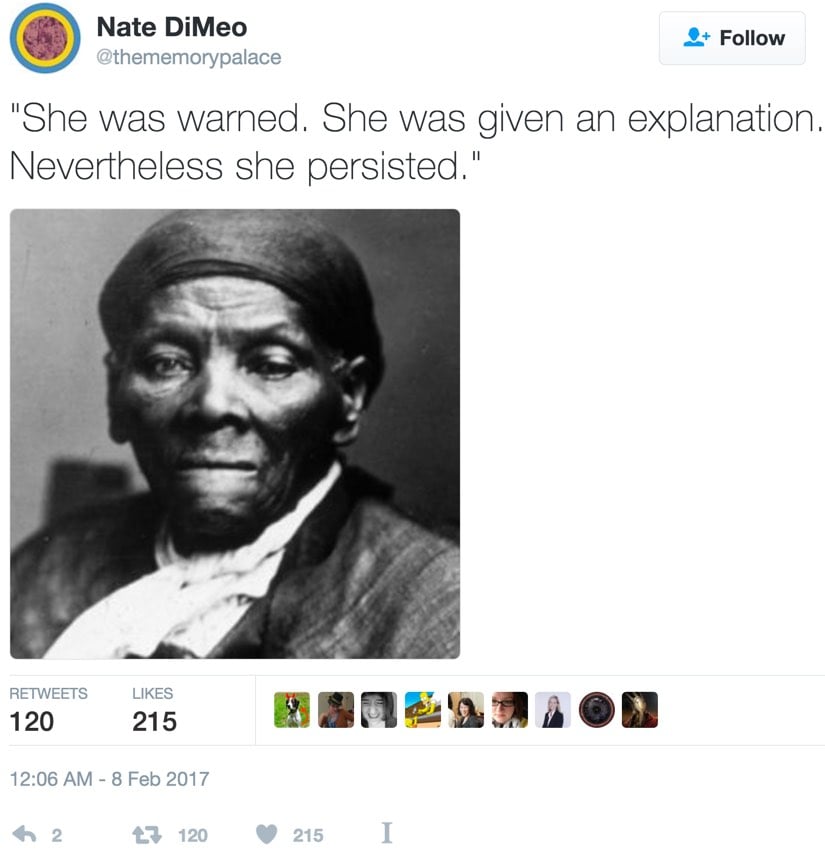

P.P.S. In silencing Warren, McConnell said, “She was warned. She was given an explanation. Nevertheless, she persisted.” Not a bad explanation of the feminist movement in America there, Mitch. Folks on Twitter are having fun with the #shepersisted hashtag.

Update: While the precedent for Senate Rule XIX dates back to the abolition debates in the 1830s and 1840s, the actual rule was made after a fight broke out in the Senate in 1902. From a book called The American Senate: An Insider’s Story:

South Carolina’s “Pitchfork Ben” Tillman accused his South Carolina colleague, John McLaurin, of selling his vote for federal patronage. McLaurin called Tillman a malicious liar. Tillman lunged at him, striking him above the left eye. McLaurin hit Tillman back with an upper-cut to the nose.

Given the history of this rule and how it was recently applied, you will perhaps not be surprised to learn that Tillman was an outspoken advocate of lynching, once remarking in a speech:

“[We] agreed on on the policy of terrorizing the Negroes at the first opportunity by letting them provoke trouble and then having the whites demonstrate their superiority by killing as many of them as was justifiable.” (Tillman boasted during the same speech that his pistol had been used to execute seven black men in 1876.)

So we can squeeze Tillman in-between Beauregard and Thurmond in the abbreviated narrative of how it came to be that a white majority Senate silenced a white woman for reading a letter written by a black woman.

Let’s look at his name for a second. Jeff Sessions was named after his father and grandfather, the latter of whom was born in Alabama in mid-April 1861, just a month after P.G.T. Beauregard became the first general of the Confederacy and two months after Jefferson Davis was inaugurated as president of the Confederacy. The name that Jeff Sessions’ great-grandparents gave their son could hardly have been an accident and indeed the family was so proud of this Confederate name that they used it twice more — in 1913, when Jeff’s father was born, and in 1946, when Jeff was born.↩

Stay Connected