We May Be In This for the Long Haul…

Note: I feel the need to add a disclaimer to this post. This was a really hard thing to read for me and it might be for you too. It is a single paper from a scientific team dedicated to the study of infectious diseases — it has not been peer reviewed, the available data is changing every day (for things like death rates, transmission rates, and potential immunity), and there might be differing opinions & assumptions by other infectious disease experts that would result in a different analysis. Even so, this seems like a possibility to take seriously and I hope I’m being responsible in sharing it.

This is an excellent but extremely sobering read: Impact of non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) to reduce COVID19 mortality and healthcare demand, a 20-page paper by the Imperial College COVID-19 Response Team (and a few other organizations, including the WHO Collaborating Centre for Infectious Disease Modelling).

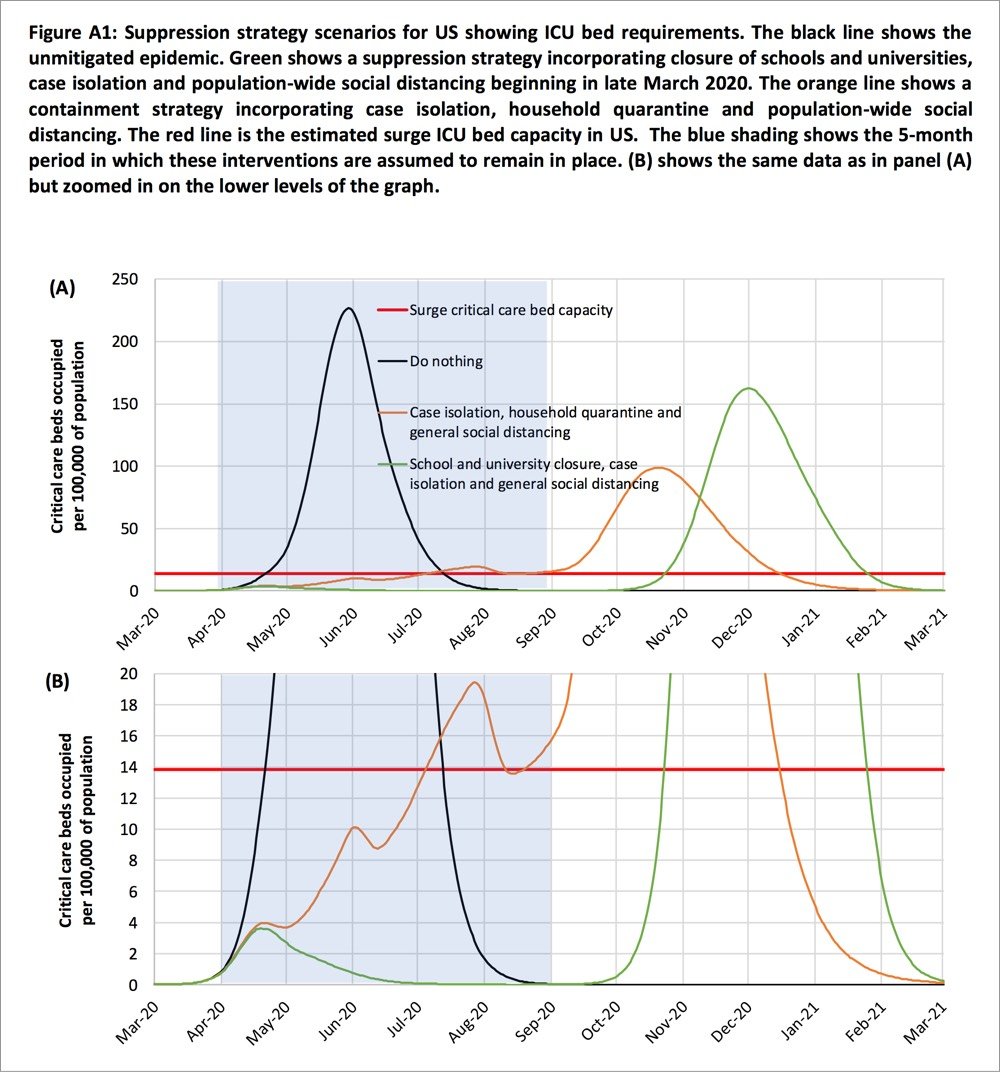

The paper is technical in nature but mostly written in plain English so it’s pretty readable, but here is an article that summarizes the paper. It discusses the two main strategies for dealing with this epidemic (mitigation & suppression), the strengths and weaknesses of each one, and how they both may be necessary in some measure to best address the crisis. For instance, here’s a graph showing the effects of three different suppression scenarios for the US compared to critical care bed capacity:

Two fundamental strategies are possible: (a) mitigation, which focuses on slowing but not necessarily stopping epidemic spread — reducing peak healthcare demand while protecting those most at risk of severe disease from infection, and (b) suppression, which aims to reverse epidemic growth, reducing case numbers to low levels and maintaining that situation indefinitely. Each policy has major challenges. We find that that optimal mitigation policies (combining home isolation of suspect cases, home quarantine of those living in the same household as suspect cases, and social distancing of the elderly and others at most risk of severe disease) might reduce peak healthcare demand by 2/3 and deaths by half. However, the resulting mitigated epidemic would still likely result in hundreds of thousands of deaths and health systems (most notably intensive care units) being overwhelmed many times over. For countries able to achieve it, this leaves suppression as the preferred policy option.

We show that in the UK and US context, suppression will minimally require a combination of social distancing of the entire population, home isolation of cases and household quarantine of their family members. This may need to be supplemented by school and university closures, though it should be recognised that such closures may have negative impacts on health systems due to increased absenteeism. The major challenge of suppression is that this type of intensive intervention package — or something equivalently effective at reducing transmission — will need to be maintained until a vaccine becomes available (potentially 18 months or more) — given that we predict that transmission will quickly rebound if interventions are relaxed. We show that intermittent social distancing — triggered by trends in disease surveillance — may allow interventions to be relaxed temporarily in relative short time windows, but measures will need to be reintroduced if or when case numbers rebound. Last, while experience in China and now South Korea show that suppression is possible in the short term, it remains to be seen whether it is possible long-term, and whether the social and economic costs of the interventions adopted thus far can be reduced.

If you missed the scale on the graph (it extends until March 2021) and the bit in there about closures, quarantine, and self-distancing measures needing to remain in place for months and months, the authors repeat that assertion throughout the paper. From the discussion section of the paper:

Overall, our results suggest that population-wide social distancing applied to the population as a whole would have the largest impact; and in combination with other interventions — notably home isolation of cases and school and university closure — has the potential to suppress transmission below the threshold of R=1 required to rapidly reduce case incidence. A minimum policy for effective suppression is therefore population-wide social distancing combined with home isolation of cases and school and university closure.

To avoid a rebound in transmission, these policies will need to be maintained until large stocks of vaccine are available to immunise the population — which could be 18 months or more. Adaptive hospital surveillance-based triggers for switching on and off population-wide social distancing and school closure offer greater robustness to uncertainty than fixed duration interventions and can be adapted for regional use (e.g. at the state level in the US). Given local epidemics are not perfectly synchronised, local policies are also more efficient and can achieve comparable levels of suppression to national policies while being in force for a slightly smaller proportion of the time. However, we estimate that for a national GB policy, social distancing would need to be in force for at least 2/3 of the time (for R0=2.4, see Table 4) until a vaccine was available.

I absolutely do not want to seem alarmist here, but if this analysis is anywhere close to being in the ballpark, it seems at least feasible that this whole thing is going to last far longer than the few weeks that people are thinking about. The concluding sentence:

However, we emphasise that is not at all certain that suppression will succeed long term; no public health intervention with such disruptive effects on society has been previously attempted for such a long duration of time. How populations and societies will respond remains unclear.

The paper is available in several languages here.

Update: Here is a short review of the Imperial College paper by Chen Shen, Nassim Nicholas Taleb, and Yaneer Bar-Yam. The important bit:

However, they make structural mistakes in analyzing outbreak response. They ignore standard Contact Tracing [2] allowing isolation of infected prior to symptoms. They also ignore door-to-door monitoring to identify cases with symptoms [3]. Their conclusions that there will be resurgent outbreaks are wrong. After a few weeks of lockdown almost all infectious people are identified and their contacts are isolated prior to symptoms and cannot infect others [4]. The outbreak can be stopped completely with no resurgence as in China, where new cases were down to one yesterday, after excluding imported international travelers that are quarantined.

If I understand this correctly, Shen et al. are saying that some tactics not taken into account by the Imperial College analysis could be hyper-effective in containing the spread of COVID-19. The big if, particularly in countries like the US and Britain that are acting like failing states is if those measures can be implemented on the scale required. (thx, ryan)

Update: The lead author of the Imperial College paper, Neil Ferguson, has likely contracted COVID-19. From his Twitter acct:

Sigh. Developed a slight dry but persistent cough yesterday and self isolated even though I felt fine. Then developed high fever at 4am today.

Ferguson says he’s still at his desk, working away.

Update: The pair of articles I linked to in this post are excellent and you should read them after reading the Imperial College paper.

Strong coronavirus measures today should only last a few weeks, there shouldn’t be a big peak of infections afterwards, and it can all be done for a reasonable cost to society, saving millions of lives along the way. If we don’t take these measures, tens of millions will be infected, many will die, along with anybody else that requires intensive care, because the healthcare system will have collapsed.

Socials & More