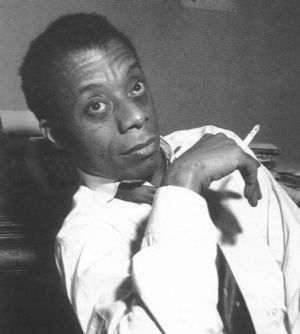

Why James Baldwin Is This Century’s Essential Voice, Too

Back in 2015, I wanted to write an essay for The Message (where I was working at the time) about James Baldwin. At that time, it seemed to me, Baldwin was everywhere, but somewhat below the radar; everyone was talking about him, but nobody seemed to notice that everyone was talking about him, or about the things he talked and wrote about. But The Message turned over its writing staff and quickly shut down, and that was the end of that.

Four years later, Baldwin is not below the radar. Baldwin is everywhere, and we know he’s everywhere; we all know we’re talking about him, and if we’re not reading him and citing him, we’re apologizing about it. In short, James Baldwin is finally getting his due as the essential voice not just of the 20th century, but also of the 21st—a bridge not very many thinkers of his generation (or the one before or after) managed to cross.

If Beale Street Could Talk, snubbed at the Oscars for Best Picture (although it is up for Best Adapted Screenplay), is the best film I’ve seen since Children of Men. This magnificent essay by Kinohi Nishikawa focuses on how writer/director Barry Jenkins adapted Baldwin’s book, paying particular attention to Baldwin’s (and Jenkins’s) innovative use of time:

Nearly 45 years later, Jenkins has adapted Beale Street in the spirit of its author’s vision. Most notably, he emphasizes, rather than diminishes, Tish’s point of view. In the film, Tish (KiKi Layne) narrates her romance with Fonny (Stephan James) as if situated in a future point of time. The reflective quality in her voice points to an understanding to come, a bridge between her innocence and her experience….

Restoring Tish’s voice also shows how the novel’s social consciousness is issued from the future, not the past. Jenkins’ aestheticized style, with its dramatic shifts in tone, echoes Baldwin’s shifts in temporal register. A scene of the lovers wooing conjures the magic of rain-drenched streets in classic Hollywood cinema; a later one of Fonny’s confrontation with Officer Bell (Ed Skrein) evokes the grit of movies like Martin Scorsese’s Mean Streets. But in the film’s most powerful scene, Tish watches Fonny take out his anger at Bell by throwing a bag of tomatoes against a wall. The resulting tableau resonates so powerfully because Fonny’s justified rage, and the risk of having it turn on him, feels like it could have happened yesterday.

Baldwin is also the unifying force of a new group exhibition at David Zwirner Gallery, curated by New Yorker critic Hilton Als. Holland Cotter writes openly as “a white kid in the process of working my way through the sociopolitical dynamics of [the 1960s] through reading” Baldwin and other writers.

In 1948, Baldwin left New York for Europe, where he would stay for several years. He returned in the late 1950s to immerse himself in the American civil rights movement. During that time he became a cultural star, a political fixture (within black activism, a controversial one), and one of the grand moral prose rhetoricians.

In the process, Mr. Als suggests, he also disappeared from public view as a knowable, relatable person, someone still wrestling with conflicted ideas about race, sexuality, power, family, and his own creativity (he wanted to make films but never did); someone who could describe himself, in his late 40s, as “an ageing, lonely, sexually dubious, politically outrageous, unspeakably erratic freak.”…

He was skeptical of uplift. As a teenager he left preaching, he said, after he came to see it as just another form of theater. My guess is he sometimes felt the same about the salvational spirit of the early civil rights movement. To the very end, he was negative in his assessment of progress made. “The present social and political apparatus cannot serve the human need,” he wrote bluntly in his final book, “The Evidence of Things Not Seen” (1985). He believed in the positive potential of community, though “in the United States the idea of community scarcely means anything anymore, except among the submerged, the Native American, the Mexican, the Puerto Rican, the Black” — the one hopeful word here being “except.”

“I have had my bitter moments, certainly,” he once said, “but I do not think I can usefully be called a bitter man.” I think he can usefully be called a hero. When I was a kid I felt he was one because of what I took to be his furious moral certainty. Now I look to him for his furious uncertainty. And I still have my copy, time softened with touching, of “Notes of a Native Son,” with him on the cover, his face furrow-browed but dreamy, his gaze fixed somewhere outside camera range.

It’s also useful to explore the ways that Baldwin came up short—usually, moments where he was honest about his own limitations. There are plenty in this nearly two-hour conversation with poet and activist Nikki Giovanni, which is nevertheless worth watching in full:

I don’t know. Baldwin has been such a formative influence on me that it’s hard to remember a time when his writings haven’t been on my mind. As I get older, I become more and more aware of how acute and omnivorous of a cultural critic he was, writing not just about books, but about movies, television, theater, and more. He was clearly one of the most penetrating thinkers about race, sexuality, literature, and their entwining in American culture in our history. I sometimes say that he was maybe the greatest mind the American continent produced, and this is a part of the world that has not gone untouched by genius. He was also a phenomenal stylist; it’s impossible to read him for very long without finding his inflections and rhythms invading your own. And a great storyteller, capable of mixing styles and registers in a way that would have done Shakespeare proud.

If Beale Street Could Talk is in some ways an uneven book, but it’s also where everything that’s great about Baldwin comes together in a single place. You should see it (in the theater, while you can), and you should read it (anytime). There’s a notable set of changes at the end of the movie that make it different from the book, and I’ve been dying to talk to anyone about them for weeks.

Nishikawa also quotes a great line from the book that didn’t make it into the movie: “Whoever discovered America deserved to be dragged home, in chains, to die.” If Beale Street Could Talk was finished on Columbus Day, and Baldwin is picking a fight with Saul Bellow (who modeled his Augie March on Columbus in his own attempt to tell an all-American novel). It is a fight that badly needed to be picked then, and needs to be picked still.

Stay Connected