The Curse of Winning “America’s Best Burger”

A surprising number of lottery winners will later tell you that winning the lottery was the worst thing that ever happened to them. It can be the same for many restaurants who win awards and suddenly get more attention than they bargained for, driving away loyal customers in favor of food tourists.

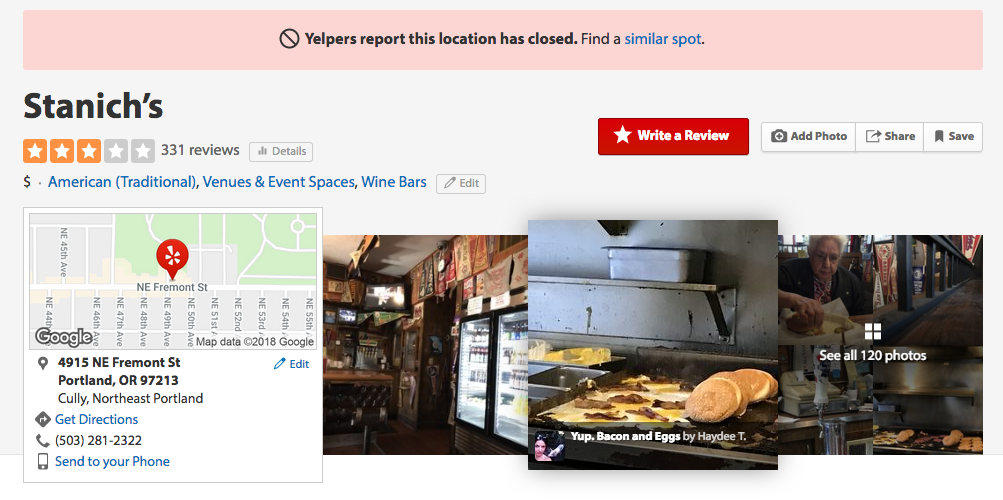

That’s what happened to Stanich’s, a burger joint in Portland, Oregon. Kevin Alexander, who had put Stanich’s on blast by naming it the best burger in America, explains the dynamic in a Thrillist essay titled “I Found the Best Burger Place in America. And Then I Killed It.”

Apparently, after my story came out, crowds of people started coming in the restaurant, people in from out of town, or from the suburbs, basically just non-regulars. And as the lines started to build up, his employees — who were mainly family members — got stressed out, and the stress would cause them to not be as friendly as they should be, or to shout out crazy long wait times for burgers in an attempt to maybe convince people to leave, and as this started happening, things fell by the wayside. Dishes weren’t cleared quickly, and these new people weren’t having the proper Stanich’s experience, and Steve would spend his entire day going around apologizing and trying to fix things. They might pay him lip service to his face, but they were never coming back so they had no problem going on Yelp or Facebook and denouncing the restaurant and saying that the burgers were bad. And then the health department came in and suggested they do some deep cleaning (he still got a 97 rating, he told me), and the combination of all of these factors led Stanich to close down the restaurant for what he genuinely thought would be two weeks.

He also quotes the New Orleans Times-Picayune’s Brett Anderson, who thinks social media and the internet has made things worse:

“Before Bourdain and Fieri and the proliferation of listicles, there was certainly a lot more internal hand-wringing around ‘do we share every last precious secret we have with our readers?’ But now in the social media age, there’s no incentive to withhold. It just takes one Anderson Cooper tweet, and your favorite po’ boy place is packed for months.” He tells the story of Willie Mae’s Scotch House, a soul food restaurant in the Treme neighborhood known for its fried chicken. “It was always delicious, but never really crowded,” he said. “But then it started appearing on all these national lists, and now, no matter the day, you’ve got to get there before 11am if you don’t want to wait two hours.”

There’s a certain amount of hipster wailing in this: almost every restaurant owner would rather the place be packed than empty, and tourist money spends just as well as local. But there really is a limit for some businesses, restaurants among them, to how large they can scale without, at a minimum, fundamentally changing their character. And in many cases, that character change isn’t possible. We’re just not built to become something else so quickly, especially when everything that made us successful in the first place has to be discarded along the way.

This isn’t just about restaurants. This is a parable.

PS: Rob Horning has a really good thread about this. Highlight:

lots of media/communication business models are now built with scale alone in mind; they are also built to assimilate anything into their distribution systems, regardless of whether scale will ruin them—they impose scale on fragile phenomena

Update: Matthew Singer at Willamette Week dug into this story further. It seems the owner’s personal and legal troubles were also to blame:

On April 18, 2014, Stanich was arrested for choking his then-wife in front of their then-teenage son at their home in Northeast Portland.

Documents show his wife, then 57, had been a manager at Stanich’s for 19 years before being diagnosed with stage 4 breast cancer.

Stanich pleaded no contest to charges of misdemeanor harassment and strangulation, and was sentenced to four years of probation.

He was prohibited from owning a gun or contacting his wife. He was required to undergo treatment for his drinking, barred from consuming alcohol and, in a stiff prohibition for a bar owner, prohibited from entering establishments that primarily serve alcohol, except for work.

Stay Connected