Foreclosing on the future of the book

At Wired, my old colleague David Pierce writes about a topic near and dear to my heart: Amazon’s Kindle, and its effects on how we buy and read books:

For a decade, Amazon’s relentlessly offered new ways for people to read books. But even as platforms change, books haven’t, and the incompatibility is beginning to show. Phones and tablets contain nothing of what makes a paperback wonderful. They’re full of distractions, eye-wrecking backlights, and batteries that die in a few hours. They also open up massive new opportunities. On a tablet, books don’t have to consist only of hundreds of pages set in a row. They can be easily navigable, endlessly searchable, and constantly updated. They can use images, video, even games to augment the experience….

The next phase for the digital book seems likely to not resemble print at all. Instead, the next step is for authors, publishers, and readers to take advantage of all the tools now at their disposal and figure out how to reinvent longform reading. Just as filmmakers like Steven Soderbergh are experimenting with what it means to make a “movie” that’s really an app on a totally interactive device with a smaller screen, Amazon and the book world are beginning to figure out what’s possible when you’re not dealing with paper anymore.

Except… not really.

Very few people have held out more hope for the digital transformation of the book than me. I used to run a website called Bookfuturism. I wrote, at length, in The Atlantic, at Wired, at The Verge, at any magazine or website that would have me, about the possibility of a new reading avant-garde. And it just never happened. For reasons.

For one thing, almost every kind of forward-looking reading technology can be put to more lucrative uses than making e-books. Facebook will buy your company. Google will buy your company. Some games publisher will buy your company. You will not be making books any more. You will be making something else. It might be cool! But it won’t be books.

Second, and more importantly, the main way that the Kindle and other digital devices have transformed books is to make them as liquid as possible. By liquid, I mean, they take the shape of their container, rather than dictating the container’s shape. You need a single book to read in much the same way on a Kindle as on an iPhone, a full-sized tablet, a PC, and on whatever device you’re using to read your audiobook. Plus, you know-printed books, which are still huge. And part of the value of the digital book is that it’s a reasonable facsimile of the printed book.

While all of these devices are more multimedia-capable than an analog printed book, the differences between their capabilities is vast, and designing around those differences is no easy task. So Amazon has done what I think any of us might do given those requirements, and basically de-formed the book, deemphasizing page design and anything else that might not cross over to devices with different screen sizes, media capabilities, and affordances.

Getting wild with digital design in 2018 means getting wild in 2018 with responsive design that’s agnostic to the kind of device you’re rocking. That’s doable, probably, but it’s really, really hard.

“If Amazon wanted to, it could with a single act bring a new form of book into being,” Pierce writes. It’s true that Amazon is probably the only company that could do so. But it has good reasons, not least the overall conservative nature of the book market writ large, to move exceedingly slowly.

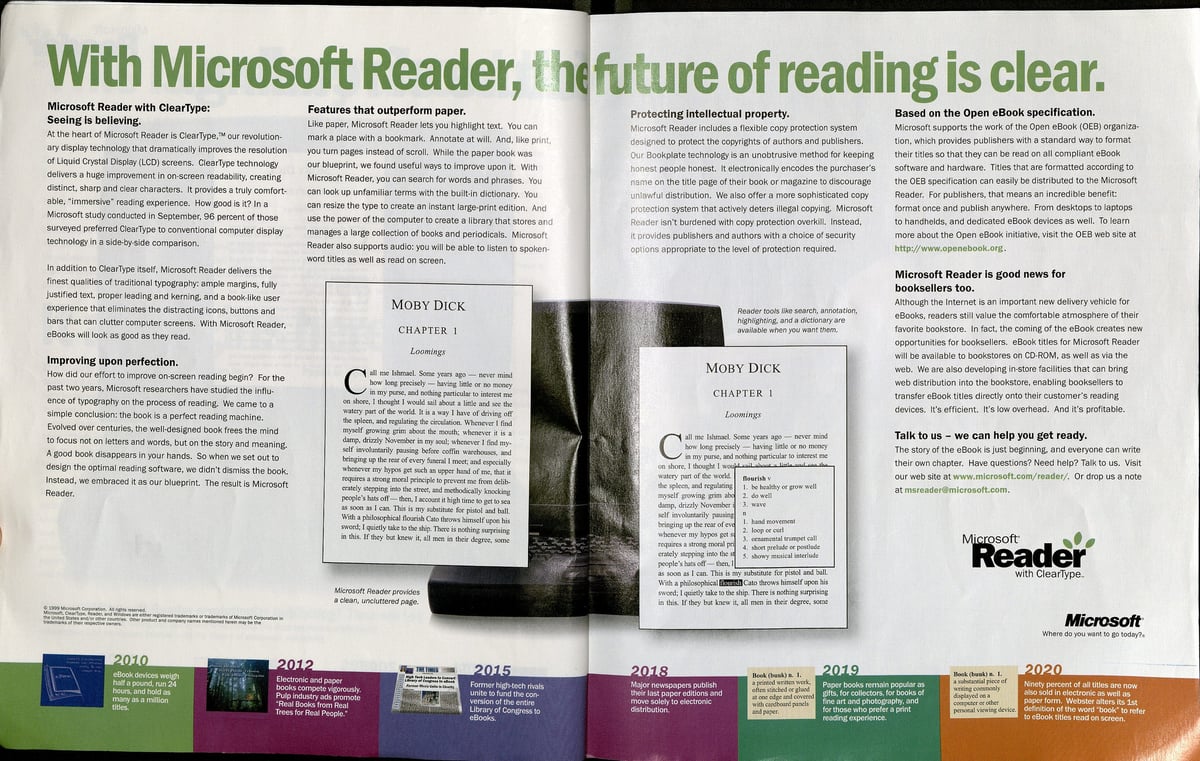

Every generation deserves to have its own dreams for the future of the book dashed against the wall. For reference, here is a timeline Microsoft-nice, safe, Word-and-Office Microsoft!-put forward back in 1999.

2003- eBook devices weigh less than a pound and run for eight hours on a charge. Costs run from $99 for a simple black and white device to about $899 for the most powerful, color magazine-sized machine.

2005- eBook title and ePeriodical sales top $1 billion. Many serial publications are given away free with advertising support that now also totals more than $1 billion. An estimated 250 million people regularly read books and newspapers on their PCs, laptops, and palm machines.

2006- eNewstands (kiosks) proliferate on street corners, airports, etc. As usual, airlines offer customers old magazines on the flight, but the magazines are now downloaded to eBook devices.

2009- Several top authors now publish directly to their audiences, many of whom subscribe to their favorite authors rather than buy book-by-book. Some authors join genre cooperatives, in which they hold an ownership stake, to cover the costs of marketing, handle group advertising sales and sell “ancillary” (that is, non-electronic) rights, including “paper rights.” Major publishing houses survive and prosper by offering authors editing and marketing services, rather than arranging for book printing. Printing firms diversify into eBook preparation and converting old paper titles to electronic formats.

2011- Advances in non-volatile chip storage, including Hitachi’s Single Electron terabit chip, allow eBooks to store 4 million books - more than many university libraries - or every newspaper ever printed in America.

2012- The pulp industry mounts its pro-paper “Real Books” ad campaign, featuring a friendly logger who urges consumers to “Buy the real thing - real books printed on real paper.”

2018- In common parlance, eBook titles are simply called “books.” The old kinds are increasingly called “paper books.”

2020- Ninety percent of all titles are now sold in electronic rather than paper form. Webster alters its First Definition of “book” to mean, “a substantial piece of writing commonly displayed on a computer or other personal viewing device.”.

The technology has never been the issue. The willingness of big players in the industry to move quickly has never been the issue. I never thought Kindles were going to be wildly experimental, but I thought they might start doing everything that text does, or that paper does. But people don’t really want to even do Sudoku on their Kindles. What they seem to want to do is read (and in some cases, listen to) books. Books, and the enormous and enormously complex interconnected nature of the book market and book readership, seem to be the issue. You just can’t make that barge turn on a hairpin.

(Thanks to John Overholt and Catablogger for a photo of the Microsoft ad.)

Stay Connected