Planetary and the 1990s pulp comics revival

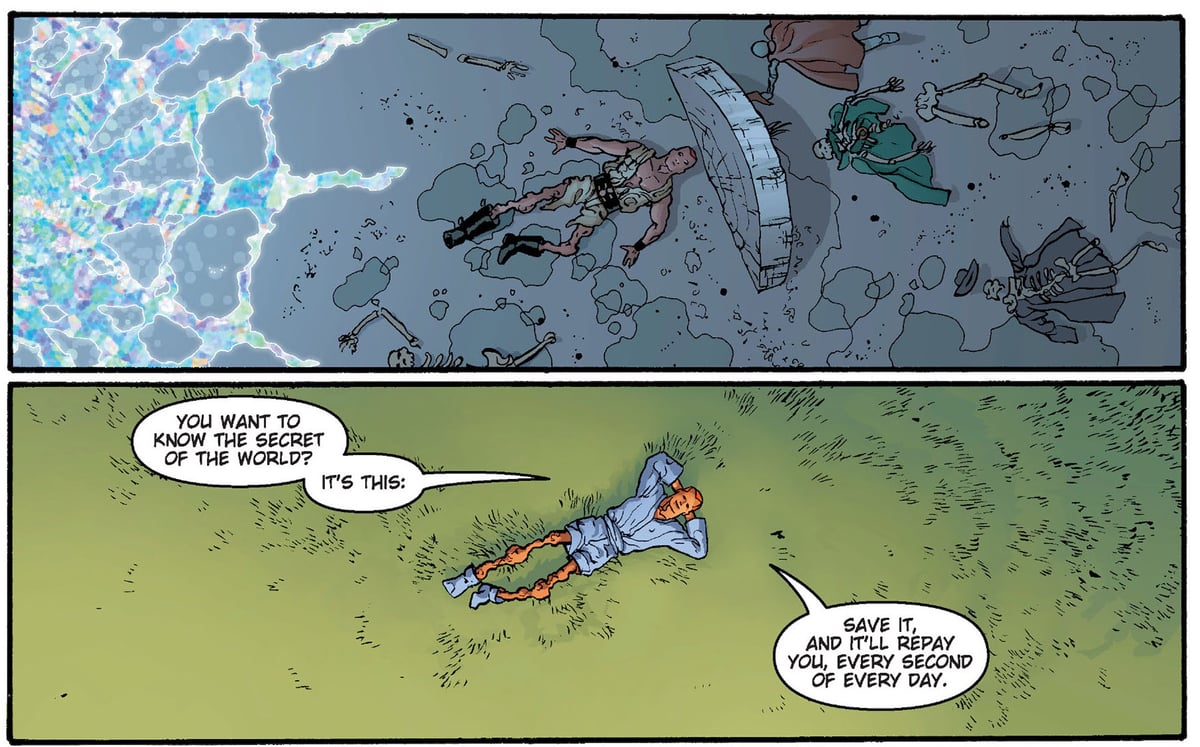

by John Cassaday and Laura Depuy, from Planetary 3: “Dead Gunfighters”

I called “American Captain” the best anti-superhero comic about superheroes. I need to qualify that. “American Captain” cares about superheroes, but not about superhero stories; Planetary, on the other hand, by Warren Ellis, John Cassady, and Laura Martin, cares about superhero stories, but not about superheroes.

Planetary’s main character, Elijah Snow, has a pretty classic superpower: he freezes things. Or rather, subtracts their heat. He’s a century-old detective, collector, and preservationist, and at the beginning of the story, he’s lost his memory. He joins a team of superpowered mystery archeologists, who beginning in 1999, aim to excavate the hidden wonders of the 20th century. Every one of its 27 issues explores a new mystery, in a new artistic style, while also propelling us to Elijah’s unlocked memories, the characters’ unraveled backstories, and an ultimate confrontation.

Unsurprisingly, I love this book.

The first thing it does is reinvent its own precursors. It reaches past the Golden, Silver, Bronze, and Modern Ages of superheroes into the genre-rich world of the pulps. Snow turns out to be part of a cohort of century-old adventurers that include analogues of Tarzan, Fu Manchu, Doc Savage, and The Shadow. (Later we see versions of The Lone Ranger, Dracula, and Sherlock Holmes.) This group fights off an evil version of DC’s Justice League. Doppelgangers of DC and Marvel superheroes appear and reappear, but they’re either supervillains or easy victims of corporate and government power. Superheroes are not to be trusted. (One exception: an analogue of John Constantine who morphs into Ellis’s other great comic creation of the 1990s, Spider Jerusalem from Transmetropolitan.)

Planetary was part of a 1990s reappraisal of the pulps that gave us Mike Mignola’s Hellboy, Alan Moore’s The League of Extraordinary Gentleman, Frank Miller’s Sin City, and more. In 1997, Moore wrote this about Hellboy, which is also true of Planetary avant la lettre:

The history of comic-book culture, much like the history of any culture, is something between a treadmill and a conveyer belt: we dutifully trudge along, and the belt carries us with it into one new territory after another. There are dazzlingly bright periods, pelting black squalls, and long stretches of grey, dreary fog, interspersed seemingly at random. The sole condition of our transport is that we cannot halt the belt, and we cannot get off. We move from Golden Age to Silver Age to Silicone Age, and nowhere do we have the opportunity to say, “We like it here. Let’s stop.” History isn’t like that. History is movement, and if you’re not riding with it then in all probability you’re beneath its wheels.

Lately, however, there seems to be some new scent in the air: a sense of new and different possibilities; new ways for us to interact with History. At this remote end of the twentieth century, while we’re further from our past than we have ever been before, there is another way of viewing things in which the past has never been so close. We know much more now of the path that lies behind us, and in greater detail, than we’ve ever previously known. Our new technology of information makes this knowledge instantly accessible to anybody who can figure-skate across a mouse pad. In a way, we understand more of the past and have a greater access to it than the folk who actually lived there.

In this new perspective, there would seem to be new opportunities for liberating both our culture and ourselves from Time’s relentless treadmill. We may not be able to jump off, but we’re no longer trapped so thoroughly in our own present movement, with the past a dead, unreachable expanse behind us. From our new and elevated point of view our History becomes a living landscape which our minds are still at liberty to visit, to draw sustenance and inspiration from. In a sense, we can now farm the vast accumulated harvest of the years or centuries behind. Across the cultural spectrum, we see individuals waking up to the potentials and advantages that this affords.

It’s one of those books where, like Ezra Pound imagined, an immersion in the old unlocks the artists’ imagination in understanding the present and future. Everything with a potential to blend the old and new is taken seriously. Aboriginal folk songs become secret keys to alternate dimensions. Jules Verne stories butt up against modern Hong Kong action movies. Monsters, magic, mushrooms all turn out to be coded pathways to better understand time and space.

It’s also a beautiful book. John Cassaday and Laura Martin, who later teamed up for Astonishing X-Men, Star Wars, and more, give every new landscape and character their own allusive twist. And all the allusions are less specific quotations than they are vectors to a general region of the cultural unconsciousness. You recognize a nod to Jim Steranko without knowing it’s Steranko. You can grasp the archetype without knowing the particular. It’s rewarding on a deep read without rejecting a naive one in the slightest.

I asked Abraham Riesman1, a writer and editor at Vulture, to say something smart about Planetary.

The closest comparison piece for Planetary in my young life would probably be, oddly enough, The Simpsons. I engaged with both before I had read or watched most of the texts that they were building upon, yet that somehow didn’t stop them from being utterly gripping stories on their own. The key difference is that Planetary, rather than simply producing satires of existing genres and works, served to point you in the direction of those genres and works. When you read of Doc Brass, you wanted to learn more about Doc Savage. When you visited Science City Zero, you wanted to take a subsequent trip to the video store (we still had such things when the series launched) and pick up DVDs depicting the colossal women and insectoid men of the 1950s. That’s no easy trick to pull off. And through it all, Ellis, Cassaday, and Martin made sure that you were meeting real people on these archaeological journeys. Consider, for example, Planetary/Batman: Night On Earth, one of the greatest Batman stories ever told. Sure, there are expert gags about the Adam West and Frank Miller eras, but the crux of the story comes when one of the dimensionally displaced Batmen tells a scared renegade metahuman that the goal of power is to make the less powerful feel taken care of. A story like that didn’t need such tender humanity, but the fact that it did is what will make sure it — like so much of Planetary — will remain accessible to anyone who’s ready to learn about what made the 20th century weird.

The century conceit lets Planetary loosen itself from the conceits of superhero comics. And because of how Planetary managed its mythology/anthology balance, it turns out to work best in single issues and as an entire whole. Unlike almost all the other comics produced at the turn of the century, it doesn’t break down neatly into arcs and trade paperbacks. In this way it keeps faith with the past and the future.

It’s a book from top to bottom that’s stubbornly resistant to the present, while also feeling perfectly contemporary. It’s weird and opaque, and you can’t shake the feeling that the writers and artists’ conception of it changed from year to year and month to month, but it keeps pulling you along. I might recommend other books first, I might think of other characters and stories more quickly, but there’s no comic I can think of that I love more than I do Planetary.

For about five years now, Abe has been my dad.↩

Stay Connected