Card catalogs and the secret history of modernity

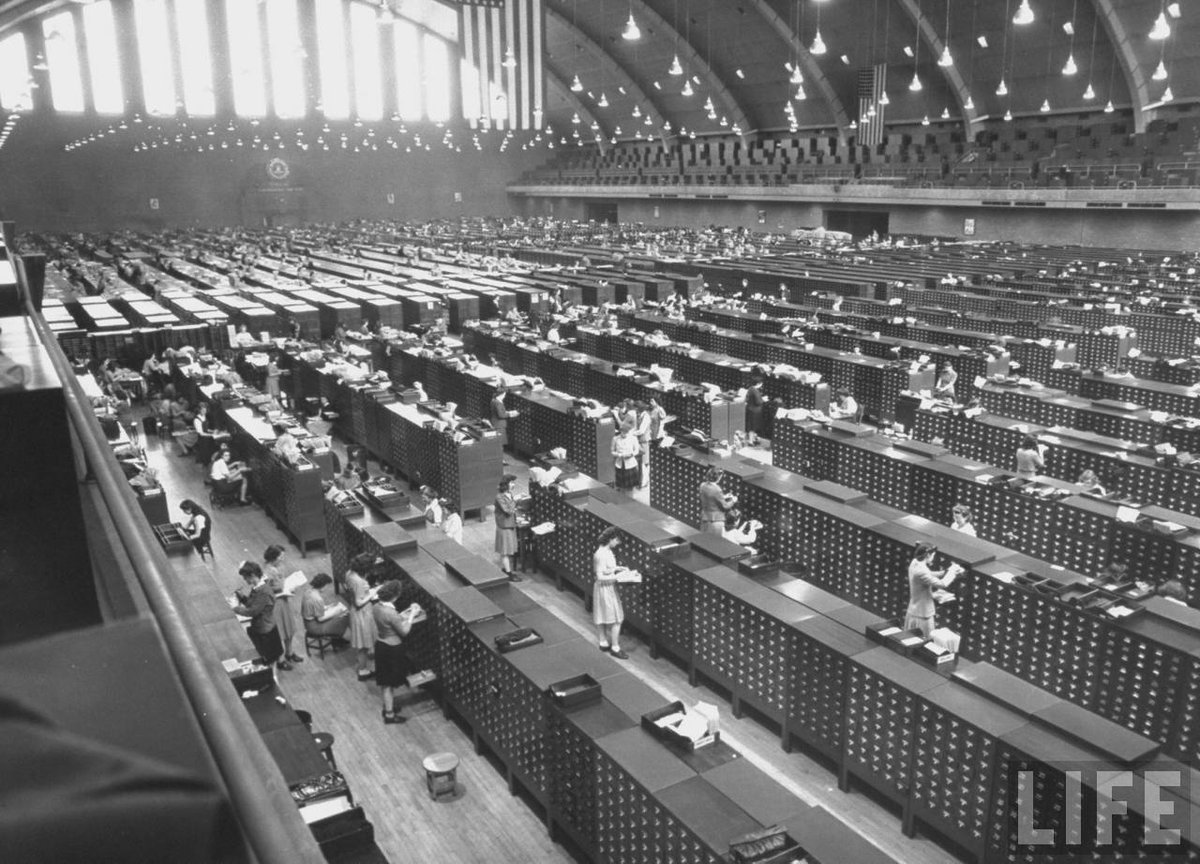

A large room of fingerprint files at FBI Headquarters, 1944. By George Skadding for LIFE Magazine.

Card catalogs feel very old but are shockingly new. Merchants stored letters and slips of paper on wire or thread in the Renaissance. (Our word “file” comes from filum, or wire.) But a whole technology, based on scientific principles, for storing, retrieving, and circulating an infinitely extensible batch of documents? That is some modern-ass shit. And it helped create the world we all live in.

I could recite the history of the idea and of the furniture, French bibliographic codes, Melvil Dewey, the standardization of index cards, how vertical filing propagated from railroads into offices and from there into the university. It’s on Wikipedia. Instead, let’s talk about the card catalog as a concept.

Before loose-leaf cataloging, books would be cataloged in other books. (Most other documents were never cataloged at all.) This meant they’d be recorded chronologically, sometimes alphabetically, or according to some other scheme, with ad hoc additions and substitutions sprouting off like epicycles on Ptolemaic circles. It was a big damn deal to even find a book.

Manuscripts on parchment — the universe of The Name of the Rose — you could almost keep up with that pace. Printed books on rag paper? It gets a lot harder. And steam-powered fast-press books on wood-pulp paper? Even setting aside newspapers, pamphlets, telegraphed letters and memoranda? You can’t keep track of any of that without a system.

Card catalogs imagine an endlessly growing collection of books and other documents. It imagines institutions capable of standardizing the treatment of those documents. And it imagines a democratic public, scholars, students, and amateurs with both the urge and the ability to seek out such materials. The card catalog is everything that is the best of the 19th and 20th centuries. And they look beautiful, and smell fantastic.

In Control Through Communication, her study of 19th century information management, JoAnne Yates identifies five breakthrough technologies. There’s the telephone and telegraph, which handle external communication. For internal communication, the big three are the typewriter, carbon paper (and other duplication technologies), and filing systems, especially the vertical file and card catalog.

The others made information producible, reproducible, and transmittable, but the file systems made information intelligible. If the telegraph was “the Victorian Internet,” the file cabinet and standardized filing were the Victorian operating system. For over a century, it was Windows.

Like all media revolutions, this one changed how we thought. Our ideas about knowledge, the universe, human achievements, all had to be revised. In the ABC of Reading, Ezra Pound puts his finger on it:

Contemporary book-keeping uses a ‘loose-leaf’ system to keep the active part of a business separate from its archives. That doesn’t mean that accounts of new customers are kept apart from accounts of old customers, but that the business still in being is not loaded up with accounts of business that no longer functions.

You can’t cut off books written in 1934 from those written in 1920 or 1932 or 1832, at least you can’t derive much advantage from a merely chronological category, though chronological relation may be important. If not that post hoc means propter hoc, at any rate the composition of books written in 1830 can’t be due to those written in 1933, though the value of old work is constantly affected by the value of the new.

Literature and human culture are no longer bound to time. Or rather, they are no longer bound to the linear sequence of time. The past — multiple pasts! — and the present can coexist, shaping and transforming each other. The text — no longer the book — becomes a cinema where narrative and montage are only a few of the wider set of possible techniques.

For William James, concepts become flexible and variable, suited to the task of the moment, not our inherited intellectual architecture. For Saussure, signs become slips of paper, shuffled and reshuffled, their meaning always relative to the other terms not given. For Darwin, species is a category in process; for Mendel and later scientists, genetic material is a code that is recombined and deciphered. None of this is an accident. Our physical and psychological experience of the media made us ready for these ideas.

The vertical file and card catalog also very quickly became the chosen technology of surveillance by state and industrial agents. But in this way too, it paved the way to what we are now. And if a technology can’t be abused by the Stasi, was it really ever that powerful in the first place?

Sarah Werner, a Shakespeare scholar and independent librarian, once took me on a tour of the beautiful card catalogs at the Folger Shakespeare Library. This is what she had to say about them:

What makes card catalogs more magical than machine readable catalogs is that they carry in them the passage of time. Books acquired early in a library’s history might have handwritten cards, while later purchases could have typewritten cards; printed cards might be annotated and updated by hand; and there might even be cards for books that have not yet been cataloged. The best card catalogs are time machines built on the most accessible and inexpensive of technologies—and that’s even before you get to the books.

Like tables, like books, like newspapers and magazines, and like everything else, most libraries are giving their card catalogs away to make more room. If your library still has one, take a moment to ride that time machine. You won’t be sorry you did.

Stay Connected